G. NEIL MARTIN

NEIL R. CARLSON

ILLIAM RUSKIST

FIFTH EDITION

ALWAYS LEARNING

PEARSON

At Pearson, we take learning personally. Our courses and

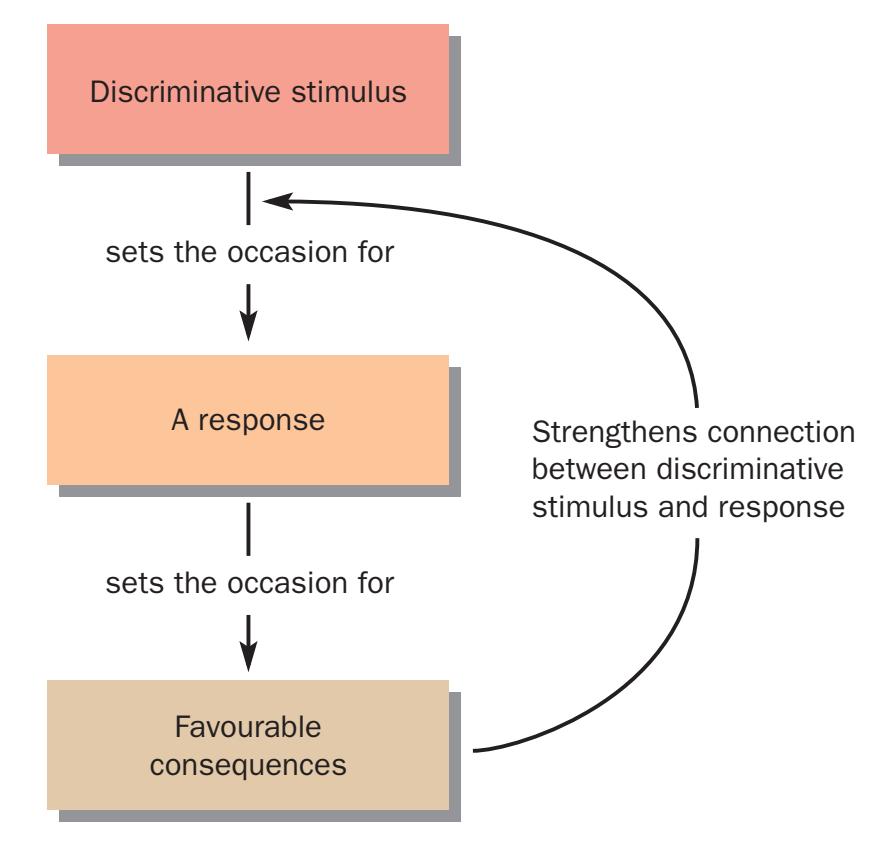

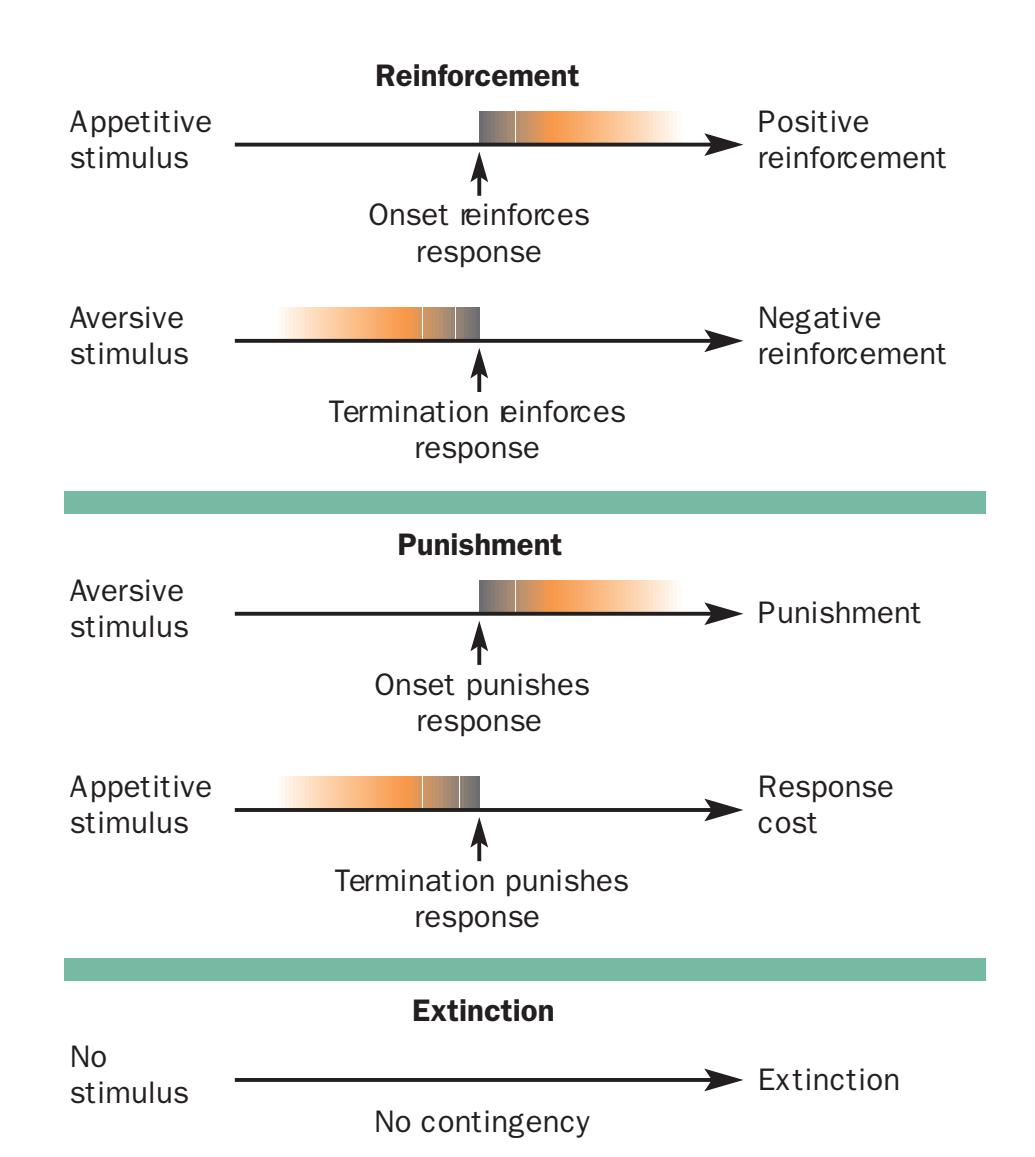

resources are available as books, online and via multi-lingual

packages, helping people learn whatever, wherever and

however they choose.

We work with leading authors to develop the strongest

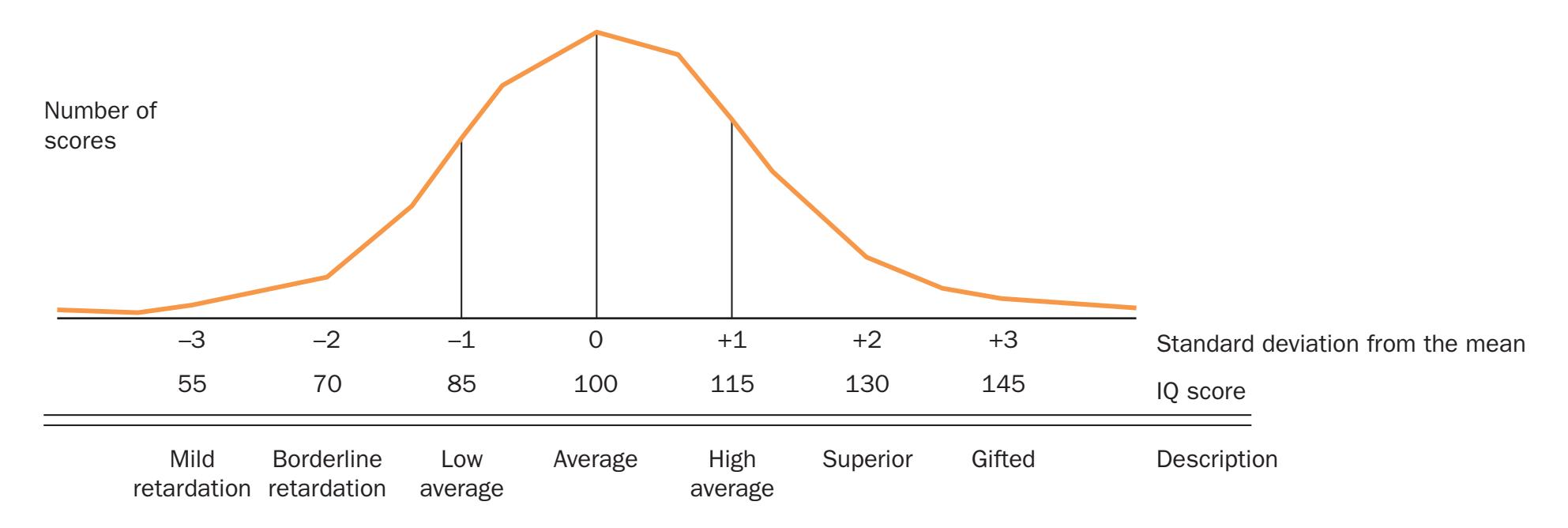

learning experiences, bringing cutting-edge thinking and best

learning practice to a global market. We craft our print and

digital resources to do more to help learners not only

understand their content, but to see it in action and apply

what they learn, whether studying or at work.

Pearson is the world's leading learning company. Our portfolio includes Penguin, Dorling Kindersley, the Financial Times and our educational business, Pearson International. We are also a leading provider of electronic learning programmes and of test development, processing and scoring services to educational institutions, corporations and professional bodies around the world.

Every day our work helps learning flourish, and wherever

learning flourishes, so do people.

To learn more please visit us at: www.pearson.com/uk

FIFTH EDITION

G. NEIL MARTIN

middlesex university, uK

NEIL R. CARLSON

university of massachusetts, usa

WI IAM BUSKIST

auburn university, usa

Harlow, England • London • New York • Boston • San Francisco • Toronto • Sydney

Auckland • Singapore • Hong Kong • Tokyo • Seoul • Taipei • New Delhi

Cape Town • São Paulo • Mexico City • Madrid • Amsterdam • Munich • Paris • Milan

#### Pearson Education Limited

Edinburgh Gate Harlow CM20 2JE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1279 623623 Web: www.pearson.com/uk

Original edition published by Allyn & Bacon, A Pearson Education Company Needham Heights, Massachusetts, USA Copyright © 1997 by Allyn and Bacon

First published by Pearson Education Limited in Great Britain in 2000 (print) Second edition published in 2004 (print) Third edition published in 2007 (print) Fourth edition published in 2010 (print) Fifth edition published in 2013 (print and electronic)

- © Pearson Education Limited 2000, 2004, 2007, 2010 (print)

- © Pearson Education Limited 2013 (print and electronic)

The rights of G. Neil Martin, Neil R. Carlson and William Buskist to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The print publication is protected by copyright. Prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, distribution or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, permission should be obtained from the publisher or, where applicable, a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom should be obtained from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.

The ePublication is protected by copyright and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased, or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and the publishers' rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Pearson Education is not responsible for the content of third-party internet sites.

ISBN: 978-0-273-75552-4 (print) 978-0-273-75559-3 (PDF) 978-0-273-78691-7 (eText)

#### **British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data**

A catalogue record for the print edition is available from the British Library

#### **Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data**

A catalog record for the print edition is available from the Library of Congress

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 17 16 15 14 13

Print edition typeset in 9.75/12pt Sabon LT Std by 30 Print edition printed and bound by L.E.G.O. S.p.A., Italy

NOTE THAT ANY PAGE CROSS REFERENCES REFER TO THE PRINT EDITION

# **Brief contents Brief contents**

| | Preface to the fifth edition | xvi |

|------------|-----------------------------------|-------|

| | Guided tour | xviii |

| | The teaching package | xxii |

| | The authors | xxiii |

| | Acknowledgements | xxv |

| | Publisher's acknowledgements | xxvii |

| 1. | The science of psychology | 2 |

| 2. | Research methods in psychology | 40 |

| 3. | Evolution, genetics and behaviour | 62 |

| 4. | Psychology and neuroscience | 96 |

| 5. | Sensation | 146 |

| 6. | Perception | 184 |

| 7. | Learning and behaviour | 224 |

| 8. | Memory | 254 |

| 9. | Consciousness | 294 |

| 10. | Language | 328 |

| 11. | Intelligence and thinking | 380 |

| 12. | Developmental psychology | 440 |

| 13. | Motivation and emotion | 498 |

| 14. | Personality | 552 |

| 15. | Social cognition and attitudes | 590 |

| 16. | Interpersonal and group processes | 622 |

| 17. | Health psychology | 666 |

| 18. | Abnormal psychology | 702 |

| Glossary | | G1 |

| References | | R1 |

| Indexes | | I1 |

# Chapter 1

# **The science of psychology**

## MyPsychLab

*Source*: Eysenck, 1957, p. 13. Explore the accompanying experiments, videos, simulations and animations on MyPsychLab. This chapter includes activities on:

- • Behaviourism

- • Little Albert

- • The Skinnerian learning process

- • Fixed-interval and fixed ratio scheduling

- • Check your understanding and prepare for your exams using the multiple choice, short answer and essay practice tests also available.

It appears to be an almost universal belief that anyone is competent to discuss psychological problems, whether he or she has taken the trouble to study the subject or not, and that while everybody's opinion is of equal value, that of the professional psychologist must be excluded at all costs because he might spoil the fun by producing some facts which would completely upset the speculation and the wonderful dream castles so laboriously constructed by the layman.

Source: Eysenck, 1957, p. 13.

#### **WhaT YOU ShOULD Be aBLe TO DO aFTer reaDING ChapTer 1**

- Defi ne psychology and trace the history of the discipline.

- Be aware of the different methods psychologists use to study behaviour.

- Distinguish between the branches of psychology and describe them.

- Understand what is meant by the 'common-sense' approach to answering questions about psychology and outline its fl aws.

- Describe and understand historical developments in psychology such as structuralism, behaviourism and the cognitive revolution.

- Be aware of how psychology developed in Europe and across the world.

#### **QUeSTIONS To ThINK aBOUT**

- How would you defi ne psychology and describe its subject matter? Once you have fi nished reading Chapter 1 , see whether your view has changed.

- What types of behaviour do you think a psychologist studies?

- Are there any behaviours that a psychologist cannot or should not study?

- What do you think psychologists mean when they say they adopt the 'scientifi c approach'?

- Should psychological research always be carried out to help people?

- Are there different types of psychologist? If so, what are they and why?

- Do you think that much of what we know from psychology is 'common sense'? Why?

- Are some psychological phenomena universal, i.e. they appear across nations and cultures?

- How does psychology differ from other disciplines, such as biology, sociology and physics? Which discipline/subjects do you think it is closest to and why?

1

4 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

## **What is psychology?**

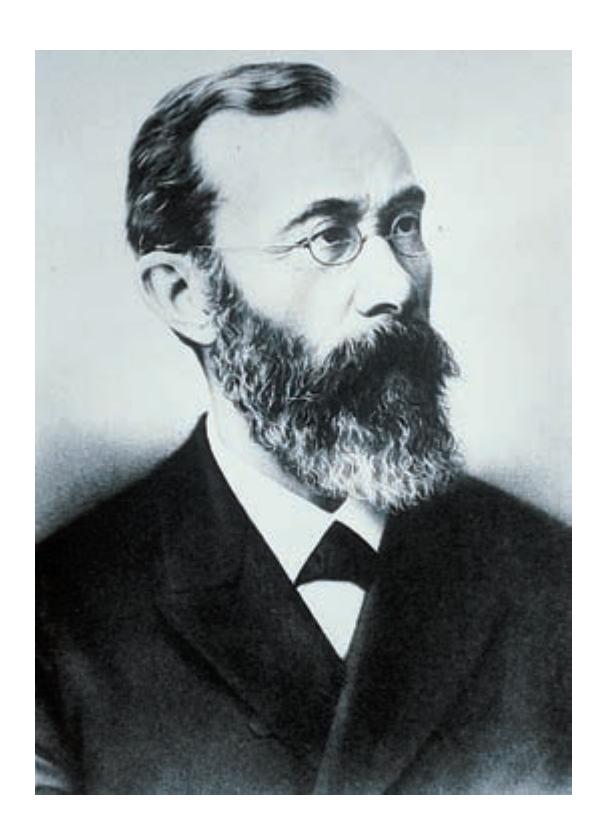

If you asked this question of several people, you would probably receive several, very different answers. In fact, if you asked this question of several psychologists, you would still not receive complete agreement on the answer. Psychologists engage in research, teaching, counselling and psychotherapy; they advise industry and government about personnel matters, the design of products, advertising, marketing and legislation; they devise and administer tests of personality, achievement and ability. And yet psychology is a relatively new discipline; the first modern scientific psychology laboratory was established in 1878 and the first person ever to call himself a psychologist was still alive in 1920. In some European universities the discipline of psychology was known as 'mental philosophy' – not psychology – even as late as the beginning of the twentieth century.

Psychologists study a wide variety of phenomena, including physiological processes within the nervous system, genetics, environmental events, personality characteristics, human development, mental abilities, health and social interactions. Because of this diversity, it is rare for a person to be described simply as a psychologist; instead, a psychologist is defined by the sub-area in which they work. For example, an individual who measures and treats psychological disorders is called a clinical psychologist; one who studies child development is called a developmental psychologist; a person who explores the relationship between physiology and behaviour might call themselves a neuro psychologist (if they study the effect of brain damage on behaviour) or a biopsychologist/physiological psychologist/ psychobiologist (if they study the brain and other bodily processes, such as heart rate). Modern psychology has so many branches that it is impossible to demonstrate expertise in all of these areas. Consequently, and by necessity, psychologists have a highly detailed knowledge of sub-areas of the discipline and the most common are listed in Table 1.1.

**Table 1.1** The major branches of psychology

| Branch | Subject of study |

|-------------------------------------------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Psychobiology/Biological psychology | Biological basis of behaviour |

| Psychophysiology | Psychophysiological responses such as heart rate, galvanic skin response and brain

electrical activity |

| Neuropsychology | Relationship between brain activity/structure and function |

| Comparative psychology | Behaviour of species in terms of evolution and adaptation |

| Ethology | Animal behaviour in natural environments |

| Sociobiology | Social behaviour in terms of biological inheritance and evolution |

| Behaviour genetics | Degree of influence of genetics and environment on psychological factors |

| Cognitive psychology | Mental processes and complex behaviour |

| Cognitive neuroscience | Brain's involvement in mental processes |

| Developmental psychology | Physical, cognitive, social and emotional development from birth to senescence |

| Social psychology | Individuals' and groups' behaviour |

| Individual differences | Temperament and characteristics of individuals and their effects on behaviour |

| Cross-cultural psychology | Impact of culture on behaviour |

| Cultural psychology | Variability of behaviour within cultures |

| Forensic and criminological psychology | Behaviour in the context of crime and the law |

| Clinical psychology | Causes and treatment of mental disorder and problems of adjustment |

| Health psychology | Impact of lifestyle and stress on health and illness |

| Educational psychology | Social, cognitive and emotional development of children in the context of schooling |

| Consumer psychology | Motivation, perception and cognition in consumers |

| Organisational or occupational psychology | Behaviour of groups and individuals in the workplace |

| Ergonomics | Ways in which humans and machines work together |

| Sport and exercise psychology | The effects of psychological variables on sport and exercise performance, and vice versa |

What is psychology? 5

#### **Psychology defined**

**Psychology** is the scientific study of behaviour. The word 'psychology' comes from two Greek words, *psukhe*, meaning 'breath' or 'soul', and *logos*, meaning 'word' or 'reason'. The modern meaning of psycho- is 'mind' and the modern meaning of -logy is 'science'; thus, the word 'psychology' literally means 'the science of the mind'. Early in the development of psychology, people conceived of the mind as an independent, free-floating spirit. Later, they described it as a characteristic of a functioning brain whose ultimate function was to control behaviour. Thus, the focus turned from the mind, which cannot be directly observed, to behaviour, which can. And because the brain is the organ that both contains the mind and controls behaviour, psychology very soon incorporated the study of the brain.

The study of physical events such as brain activity has made some psychologists question whether the word 'mind' has any meaning in the study of behaviour. One view holds that the 'mind' is a metaphor for what the brain does and because it is a metaphor it should not be treated as if it actually existed. In his famous book *The Concept of Mind*, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle describes this as the 'ghost in the machine' (Ryle, 1949). One might, for example, determine that the personality trait of extroversion exists and people will fall on different points along a dimension from not very extrovert to very extrovert. But does this mean that this trait really exists? Or is it a label used to make us understand a complex phenomenon in a simpler way? This is called the problem of **reification** in psychology: the assumption that an event or phenomenon is concrete and exists in reality because it is given a name.

The approach adopted by modern psychology is scientific, that is, it adopts the principles and procedures of science to help answer the questions it asks. Psychologists adopt this approach because it is the most effective way of determining 'truth' and 'falsity'; the scientific method, they argue, incorporates fewer biases and greater rigour than do other methods. Of course, not all approaches in psychology have this rigorous scientific leaning: early theories of personality, for example, did not rely on the scientific method (these are described in Chapter 14) and a minority of psychologists adopt methods that are not considered to be part of the scientific approach: qualitative approaches to human behaviour, for example (reviewed in Chapter 2).

## **How much of a science is psychology?**

Psychology is a young science and the discipline has tried hard to earn and demonstrate its scientific spurs. Chemistry, physics or biology seem to have no such problems: their history is testament to their status as a science. Psychology, however, appears to be gaining ground.

Simonton (2004) compared the scientific status of psychology with that of physics, chemistry, sociology and biology, using a number of characteristics that typified a general science. These included the number of theories and laws mentioned in introductory textbooks (the higher the ratio of theory to law, the 'softer' – i.e. less scientific – the discipline); the discipline's publication rate (the more frequent the publications, the more scientific the discipline); appearance of graphs in journal papers (the 'harder' the discipline, the greater the number of graphs); the number of times publications were referred to by other academics; and how peers evaluated their colleagues. Simonton also looked at other measures of scientific standing such as 'lecture disfluency' (the number of pause words such as 'uh', 'er' and 'um': these are more common in less formal, structured and factual disciplines); and perceived difficulty of the discipline.

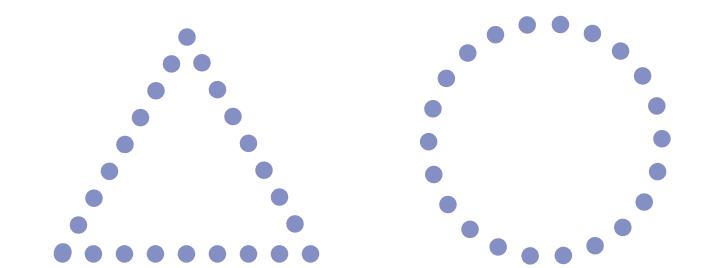

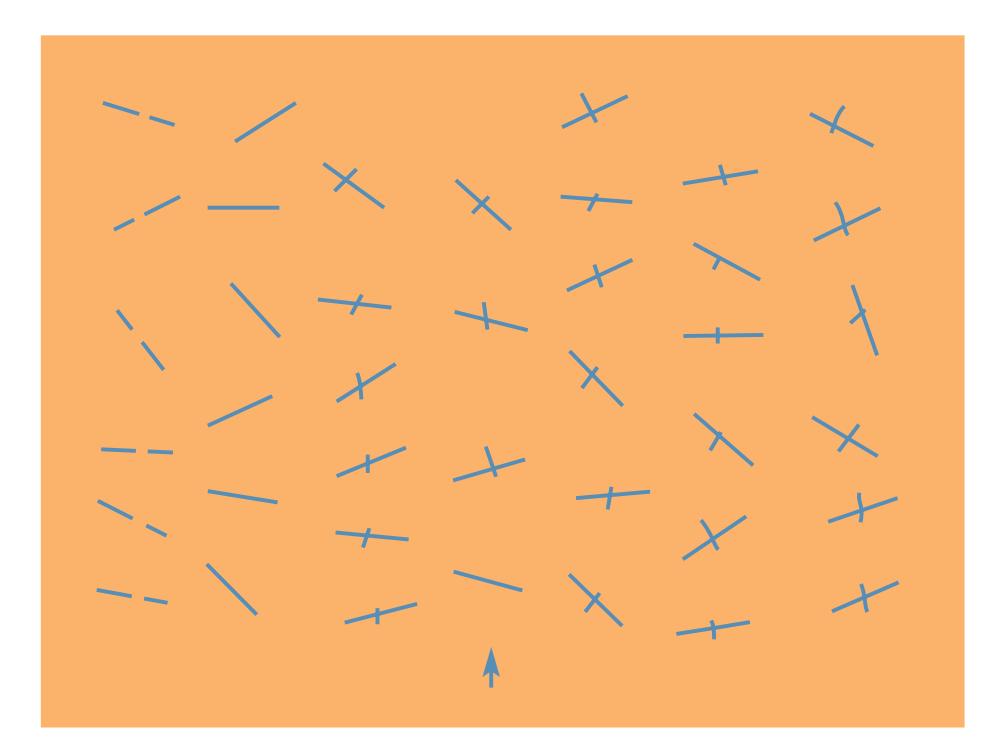

Not surprisingly, Simonton found that the natural sciences were judged to be more 'scientific' than were the social sciences. Psychology, however, fell right on the mean – at the junction between natural and social sciences, as you can see in Figure 1.1, and was much closer to biology than to sociology. The biggest gap in scores was found between psychology and sociology, suggesting that the discipline is closer to its natural science cousins than its social science acquaintances.

**Figure 1.1** According to Simonton's study, psychology's scientific status was more similar to that of biology than other disciplines traditionally associated with it, such as sociology.

*Sou*rce: D.K. Simonton, 'Psychology's status as a scientific discipline: its empirical placement within an implicit hierarchy of the sciences', *Review of General Psychology*, 2004, 8, 1, p. 65 (Fig. 2).

6 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

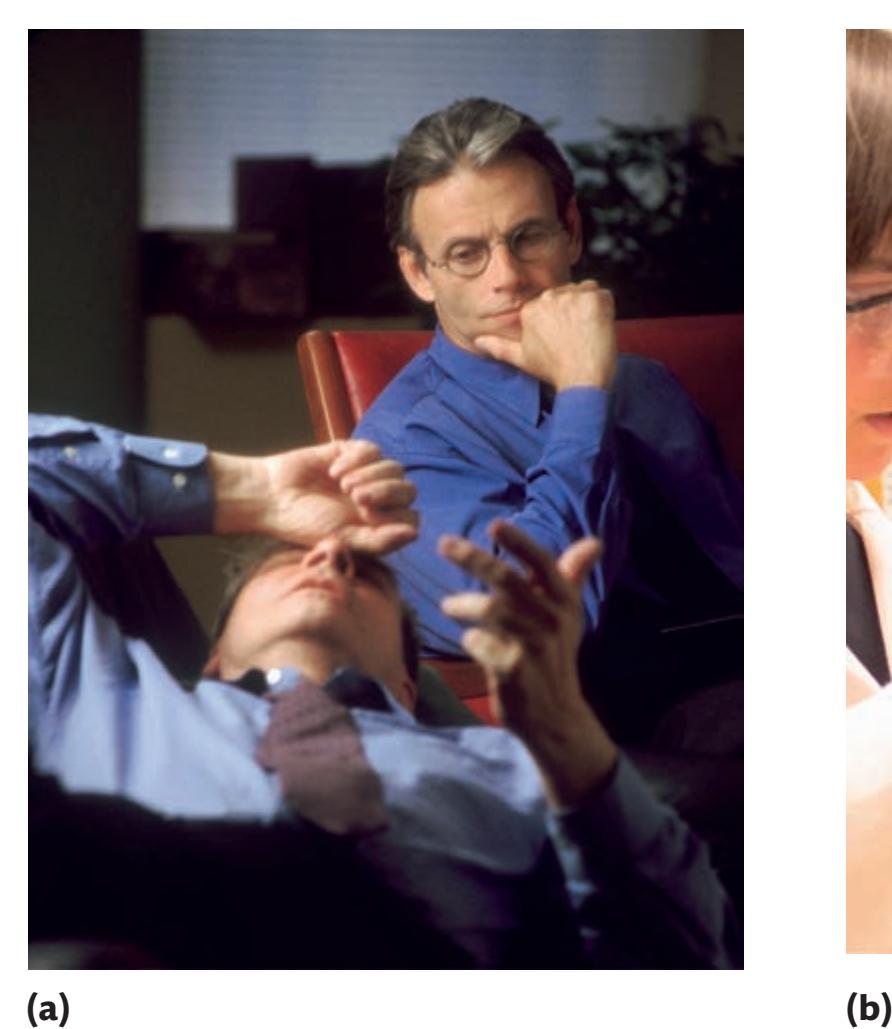

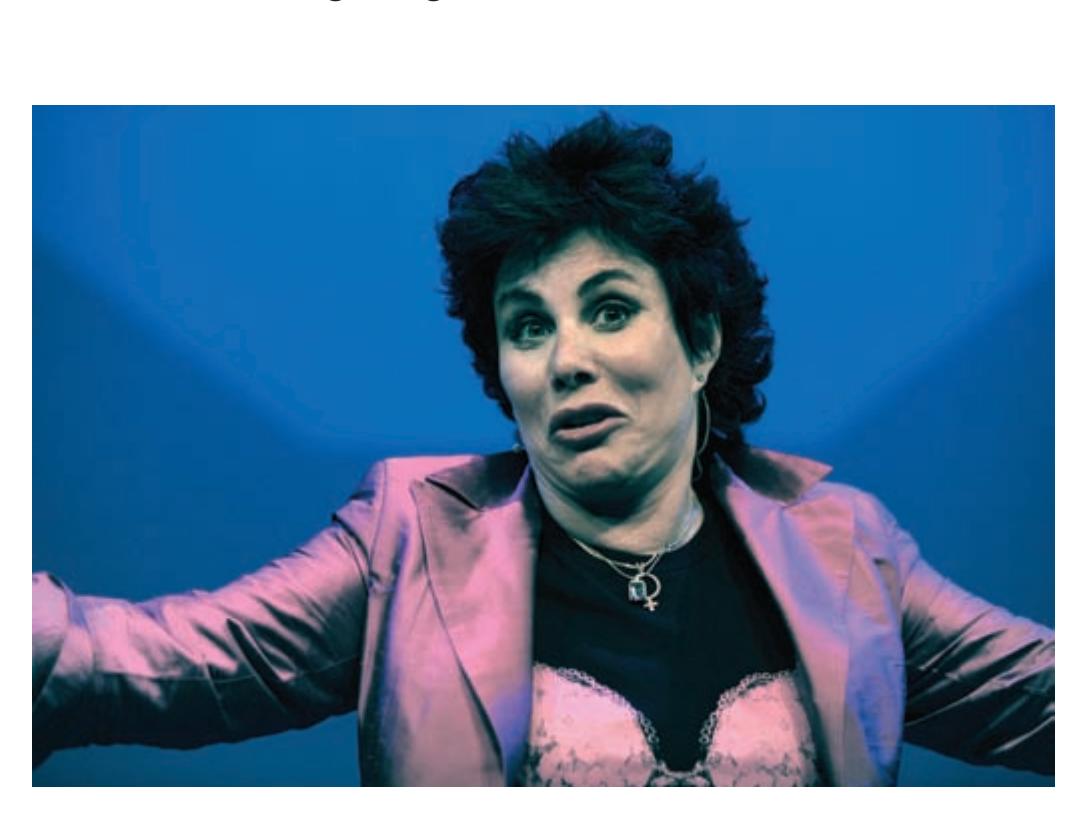

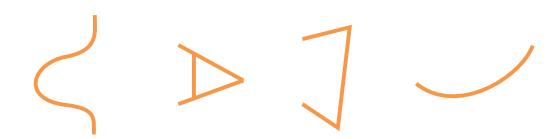

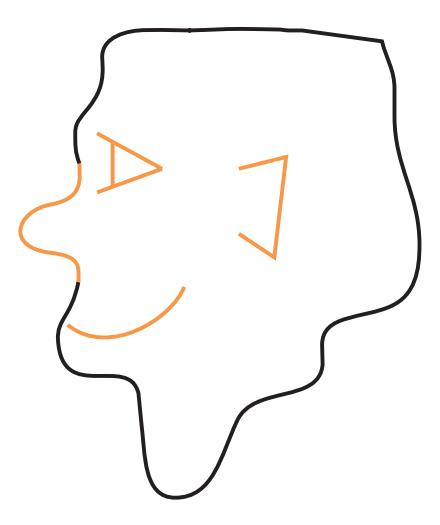

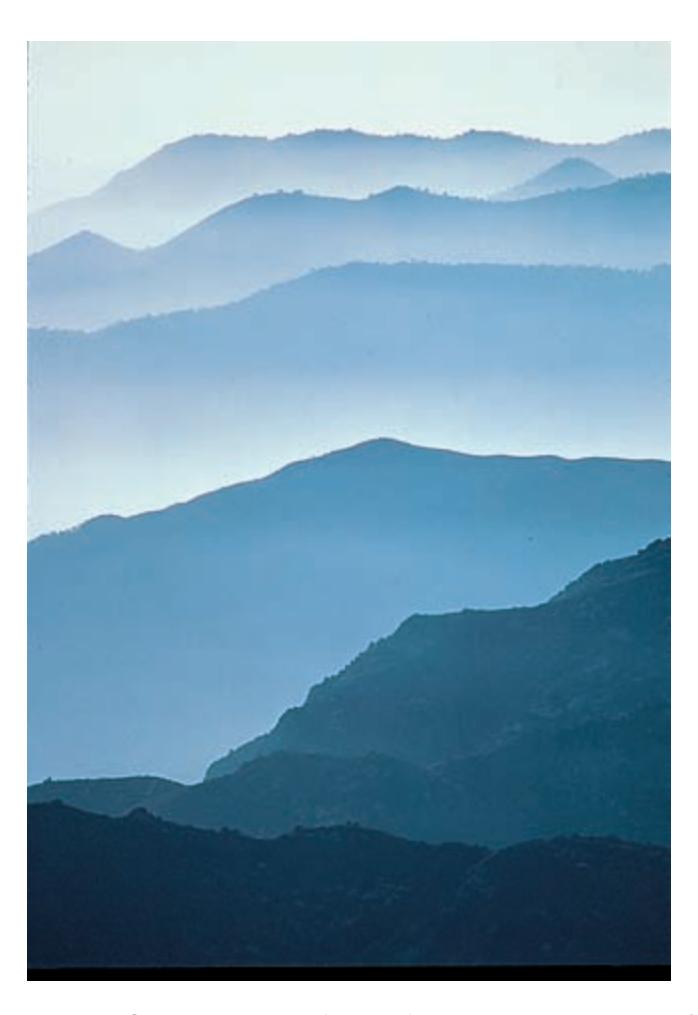

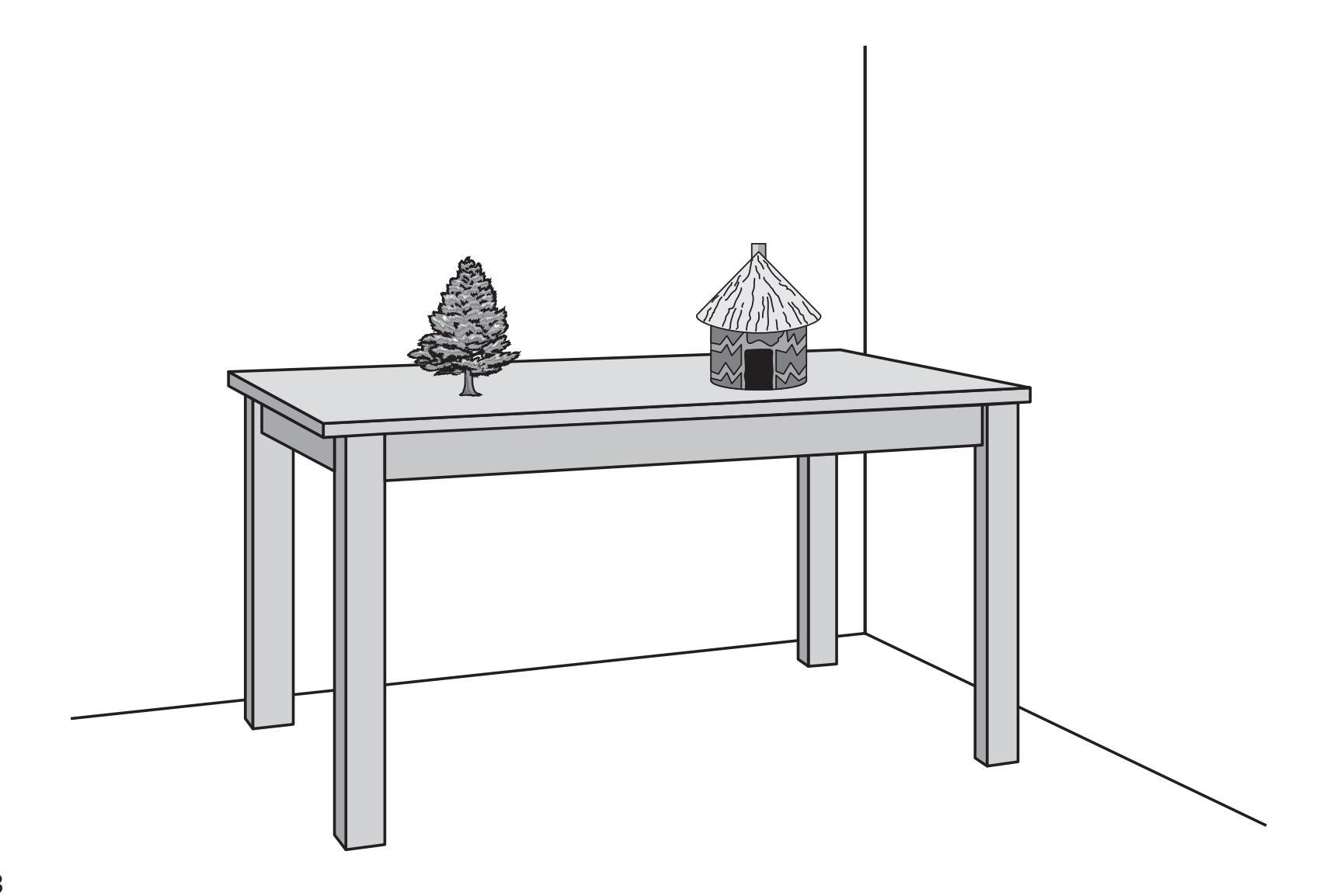

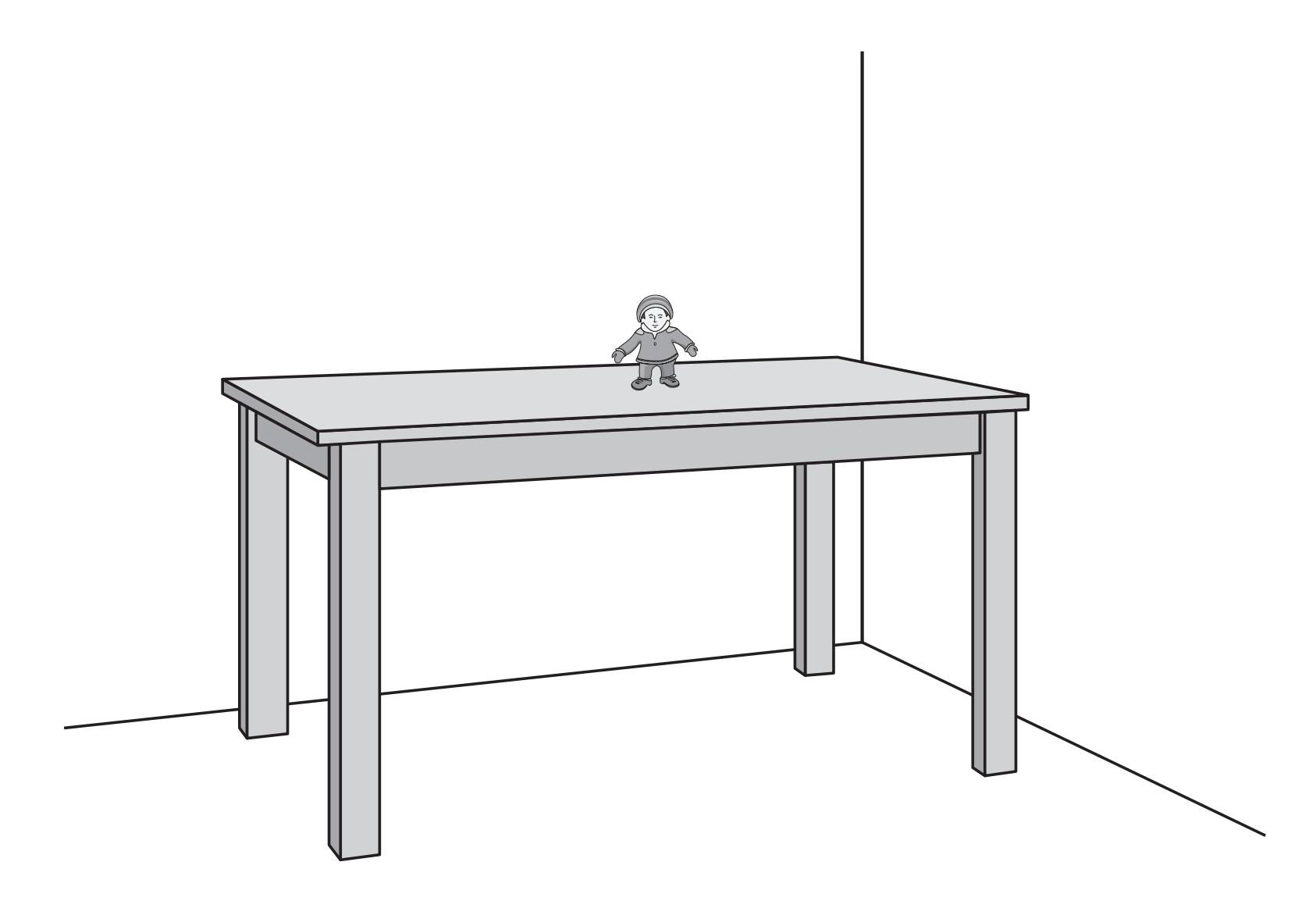

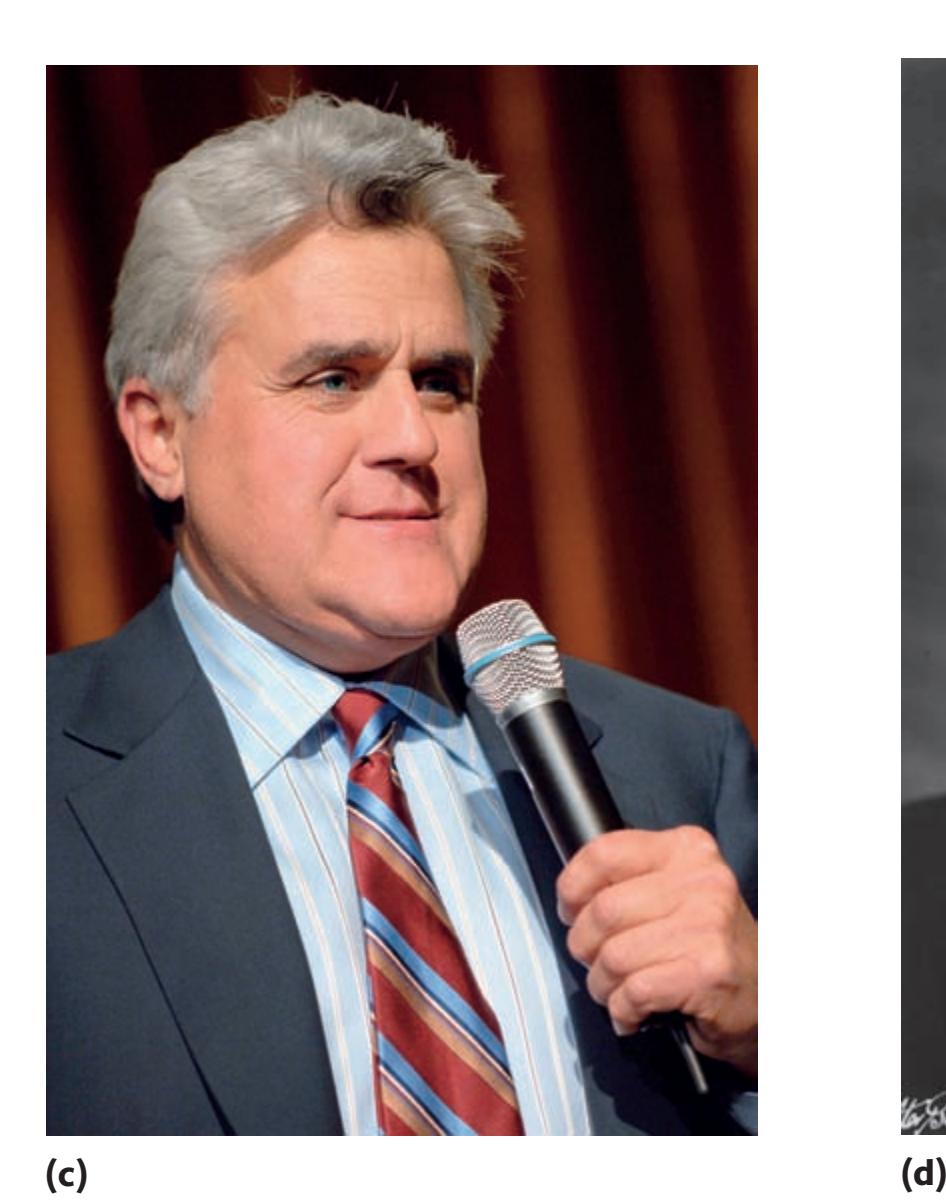

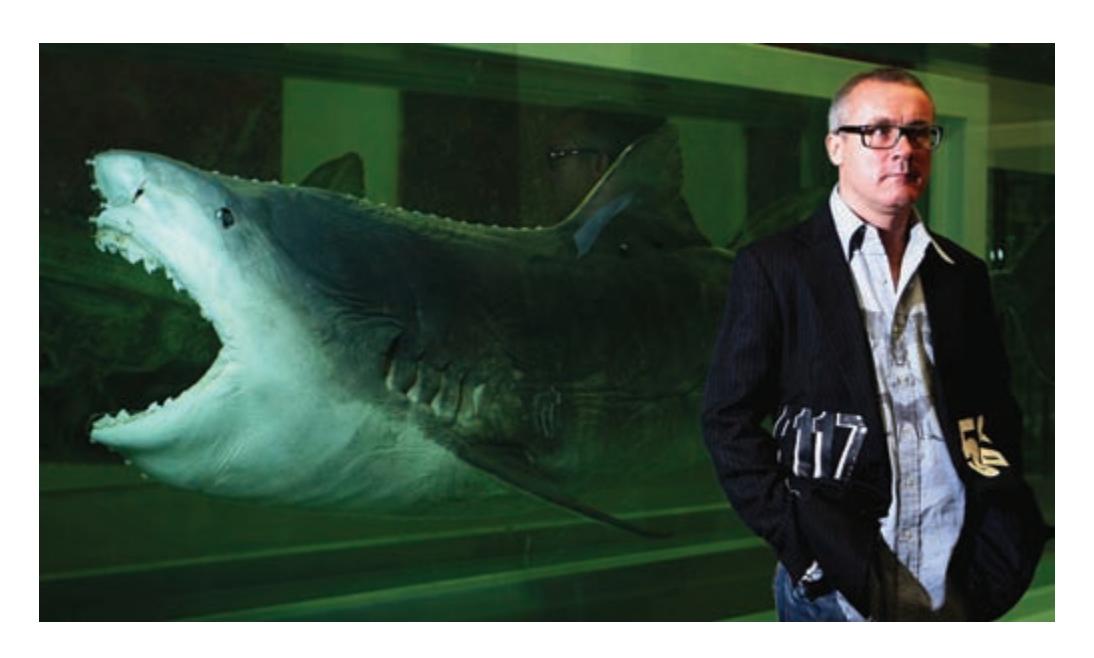

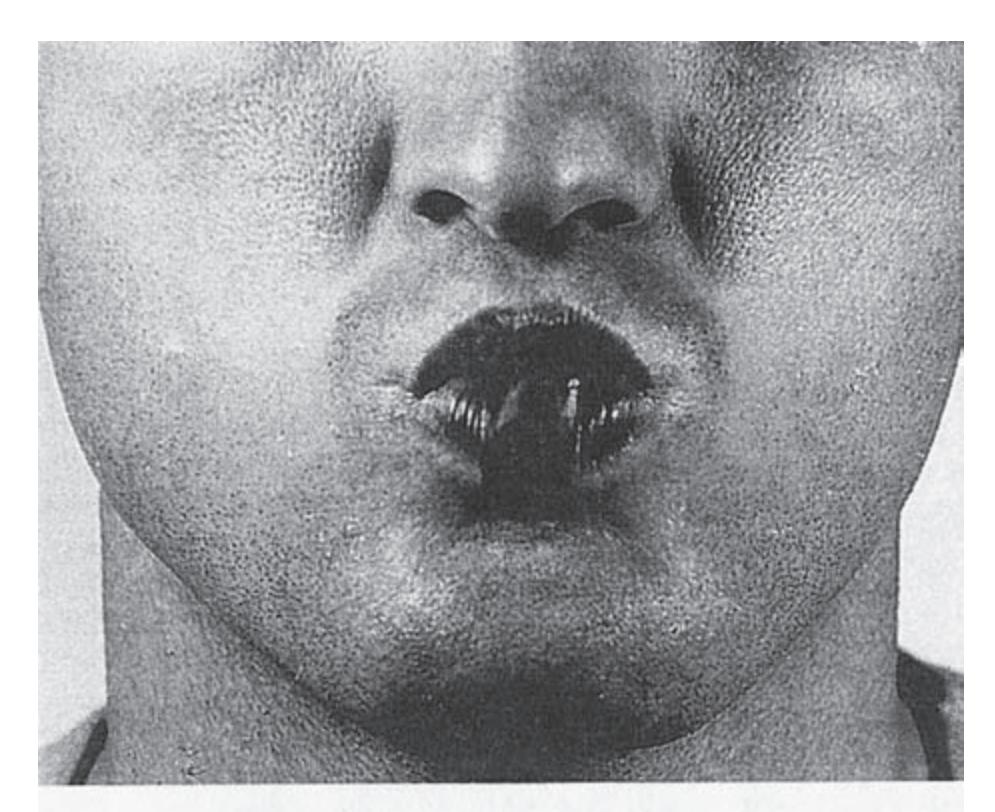

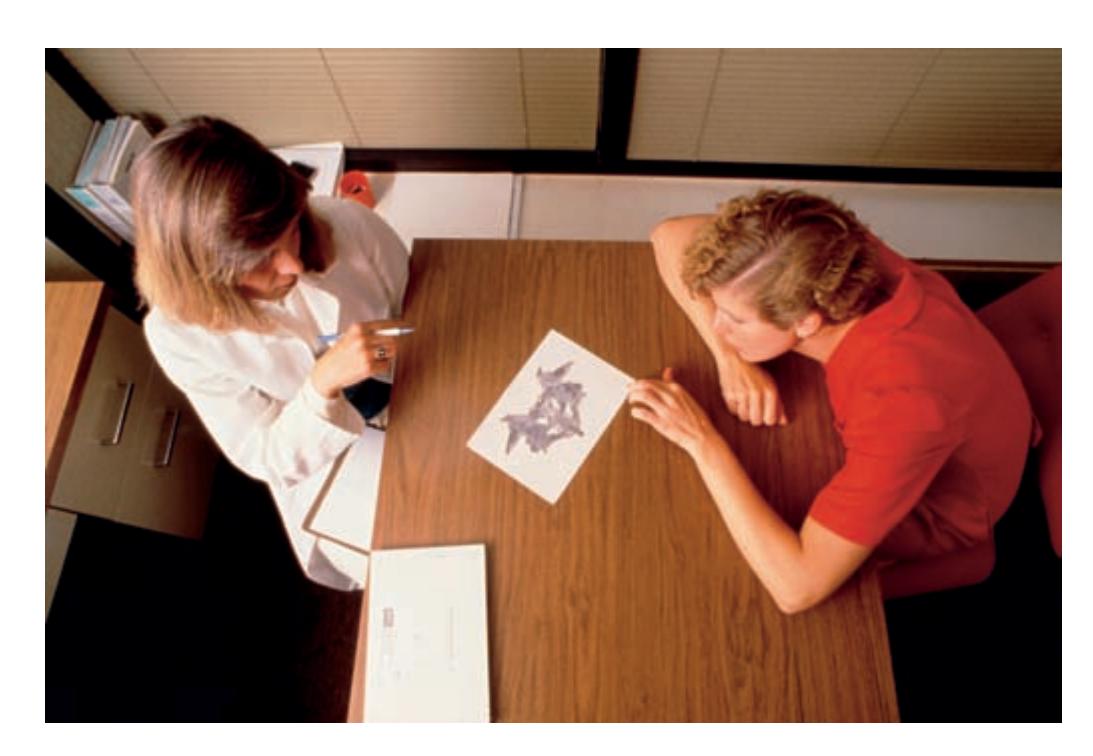

The stereotypical image of a psychologist **(a)** and a traditional scientist **(b)**.

*Source*: (a) Pelaez Inc./Corbis; (b) Tomas de Arno/Alamy Images.

A gap also separated chemistry and biology, suggesting that the sciences might be grouped according to three clusters: the physical sciences (chemistry and physics), life sciences (biology and psychology) and social science (sociology).

When does this understanding of a hierarchy of science develop? Researchers at Yale University sought to answer this question in a group of kindergarten children, school children and university students (Keil *et al*., 2010). In one experiment, participants read a series of questions about a topic from each discipline and asked them to rate the difficulty of understanding these topics. For example, for physics one of the questions was 'How does a top stay spinning upright?', for chemistry, 'Why does paper burn but not aluminium foil?', for biology, 'Why are we allergic to some things but not others?', for psychology, 'Why is it hard to understand two people talking at once?' and for economics, 'Why do house prices go up and down over the years?' Children judged questions from the natural science to be more difficult to understand than those from psychology. The difficulty of economics subsided after late childhood.

In their second experiment, the researchers examined whether different branches of psychology were perceived as being more difficult than others (e.g., neuroscience, sensation and perception, cognitive psychology, social psychology, attention and memory, personality and emotions). Children regarded neuroscience as more difficult than cognitive psychology, and cognitive psychology as more difficult than social psychology. They were judged equally 'difficult' by adults.

Simonton concluded his study with an interesting observation. He argued that psychology's position in this hierarchy does not really reflect its scientific approach but its subject matter: because the subject matter of psychology can be viewed as not directly controllable or manipulable it may be perceived erroneously, despite its adoption of the scientific method, as neither scientific fish nor fowl.

For the moment, however, consider the value of the scientific approach in psychology. Imagine that you were allowed to answer any psychological question that you might want to ask: what is the effect of language deprivation on language development, say, or the effect of personality on the stability of romantic relationships, or the effect of noise on examination revision? How would you set about answering these questions? What approach do you think would be the best? And how would you ensure that the outcome of your experiment is determined only by those factors you studied and not by any others? These are the types of problem that psychologists face when they design and conduct studies.

Sometimes, the results of scientific studies are denounced as 'common sense': that they were so obvious as to be not worth the bother of setting up an experiment. The view, however, is generally ill-informed because, as you will discover throughout this book, psychological research frequently contradicts common-sense views. As the late, influential British psychologist Hans Eysenck noted in this chapter's opening quote, most people believe that they are experts in human behaviour. And to some extent we are all lay scientists, of a kind, although generally unreliable ones. What is psychology? 7

As Lilienfeld (2011) points out: people also overestimate their understanding of how toilets, zippers and sewing machines work. And humans are slightly more complicated than a lavatory. We are also likely to discount scientific explanations for phenomena, especially if they contradict our views of these phenomena. Munro (2010), for example, presented undergraduates with scientific research which either discounted their view of homosexuality or supported it. If the evidence was not to the participants' liking, they were more dismissive of the scientific method. This attitude then carried over into another study in which the same participants were asked to make a judgement about whether science could assist making decisions about the retention of the death penalty. Those whose views had been challenged by science in the previous study were less likely to find science helpful in making decisions about other, unrelated topics. The Controversies section takes up this point.

## **Controversies in psychological science:** Is psychology common sense?

#### The issue

Take a look at the following questions on some familiar psychological topics. How many you can answer correctly?

- 1 Patients with schizophrenia suffer from a split personality. Is this: (a) true most of the time; (b) true some of the time; (c) true none of the time; (d) true only when the individual is undergoing psychotherapy?

- 2 Under hypnosis, a person will, if asked by a hypnotist: (a) recall past life events with a high degree of accuracy; (b) perform physical feats of strength not possible out of hypnosis; (c) do (a) and (b); (d) do neither (a) nor (b)?

- 3 The learning principles applied to birds and fish also apply to: (a) humans; (b) cockroaches; (c) both (a) and (b); (d) neither (a) nor (b)?

- 4 Are physically attractive people: (a) more likely to be stable than physically unattractive people; (b) equal in psychological stability; (c) likely to be less psychologically stable; (d) likely to be much more unstable?

How well do you think you did? These four questions featured in the ten most difficult questions answered by firstyear psychology undergraduates who completed a 38-item questionnaire about psychological knowledge (Martin *et al*., 1997). In fact, when the responses from first- and final-year psychology, engineering, sociology, English and business studies students were analysed, no one group scored more than 50 per cent correct. Perhaps not surprisingly, psychologists answered more questions correctly than the other students, with sociologists following close behind. But why should psychology (and other) students perform so badly on a test of psychological knowledge?

The answer lies in the fact that the questionnaire was not really a test of psychological knowledge but of common-sense attitudes towards psychological research. Common-sense mistakes are those committed when a person chooses what they think is the obvious answer but this answer is incorrect. Some writers have suggested that 'a great many of psychology's basic

principles are self-evident' (Houston, 1983), and that 'much of what psychology textbooks purport to teach undergraduates about research findings in the area may already be known to them through common, informal experiences' (Barnett, 1986). Houston reported that although introductory psychology students answered 15 out of 21 questions about 'memory and learning' correctly, a collection of 50 individuals found in a city park on a Friday afternoon scored an average of 16. The 21 December 2008 edition of *The Sunday Times* featured a full-page article, boldly headed 'University of the bleedin' obvious', in which the journalist bemoaned what he perceived to be the triviality of (mostly) behavioural research. 'Why are we,' demanded the journalist or his angry sub-editor, 'deluged with academic research "proving" things that we know already?', citing a string of what was considered irritating, self-evident bons mots from various university departments.

Is the common-sense view of psychological research justified?

#### The evidence

Not quite. Since the late 1970s, a number of studies have examined individuals' false beliefs about psychology, and students' beliefs in particular. Over 76 per cent of first-year psychology students thought the following statements were true: 'Memory can be likened to a storage chest in the brain into which we deposit material and from which we can withdraw later', 'Personality tests reveal your basic motives, including those you may not be aware of ', and 'Blind people have unusually sensitive organs of touch'. This, despite the fact that course materials directly contradicted some of these statements (Vaughan, 1977).

Furnham (1992, 1993) found that only half of such 'common-sense' questions were answered correctly by 250 prospective psychology students, and only 20 per cent of questions were answered correctly by half or more of a **sample** of 110 first-year psychology, fine arts, biochemistry and engineering students. In Martin *et al*.'s (1997) study, final-year students answered more questions correctly than did first-year students, but there was no

▲

8 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

## **Controversies in psychological science:** *Continued*

significant difference between first- and final-year psychology students. This suggests that misperceptions are slowly dispelled after students undergo the process of higher education and learning, but that studying specific disciplines does nothing to dispel these myths effectively. This is just one explanation.

What, then, is 'common' about 'common sense'? Some have likened common sense to fantastical thinking. This describes ways of reasoning about the world that violate known scientific principles (Woolley, 1997). For example, the beliefs that women can control breast cancer by positive thinking (Taylor, 1983), that walking under a ladder brings bad luck and that touching wood brings good luck (Blum and Blum, 1974) violate known physical laws, but people still believe in doing such things. People often draw erroneous conclusions about psychological knowledge because they rely on small sets of data, sometimes a very

small set of data (such as a story in a newspaper or the behaviour of a friend).

### Conclusion

As you work through your psychology course and through this book, discovering new and sometimes complicated ways of analysing and understanding human behaviour, you will realise that many of the beliefs and perceptions you held about certain aspects of psychology are false or only half right. Of course, no science is truly infallible and there are different ways of approaching psychological problems (and perhaps, sometimes, some problems are insoluble or we have no good method of studying them satisfactorily). Psychology, however, attempts to adopt the best of scientific approaches to understanding potentially the most unmanageable of subject matter: behaviour. And, for those of you who were wondering, the answers to the questions at the start of the box are c, d, c and a.

### **Explaining behaviour**

The ultimate goals of research in psychology are to understand, predict and change human behaviour: to explain why people do what they do. Different kinds of psychologists are interested in different kinds of behaviour and different levels of explanation. How do psychologists 'explain' behaviour?

First, they must describe it accurately and comprehensively. We must become familiar with the things that people (or other animals) do. We must learn how to categorise and measure behaviour so that we can be sure that different psychologists in different places are observing the same phenomena. Next, we must discover the causes of the behaviour we observe – those events responsible for its occurrence. If we can discover the events that caused the behaviour to occur, we have 'explained' it. Events that cause other events (including behaviour) to occur are called **causal events** or **determinants**.

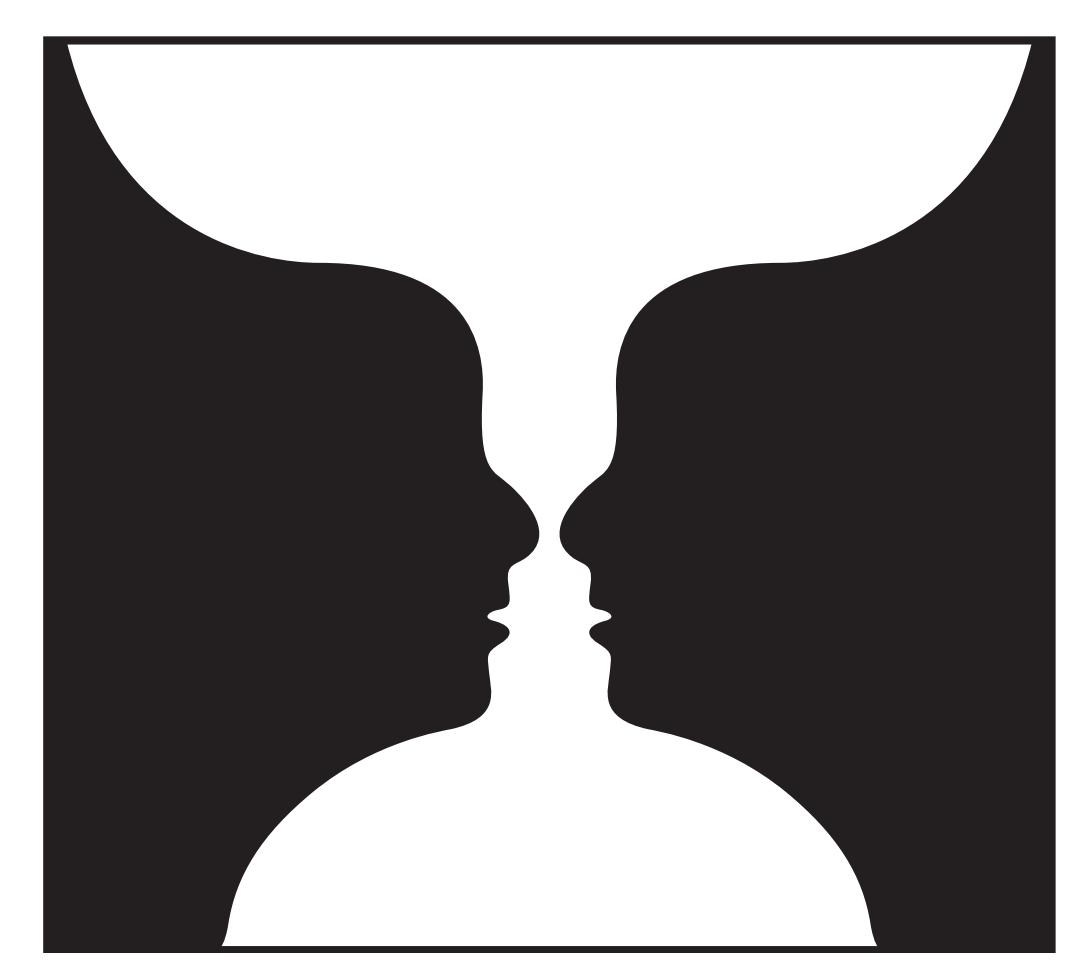

For example, one psychologist might be interested in visual perception and another might be interested in romantic attraction. Even when they are interested in the same behaviour, different psychologists might study different levels of analysis. Some look inside the organism in a literal sense, seeking physiological causes, such as the activity of nerve cells or the secretions of glands. Others look inside the organism in a metaphorical sense, explaining behaviour in terms of hypothetical mental states, such as anger, fear, curiosity or love. Still others look only for events in the environment (including things that other people do) that cause behaviours to occur.

## **Cutting edge:** Are beautiful people good because they are desired?

Research has shown that beautiful people are rated more positively than their less attractively endowed counterparts. However, their beauty may also affect our perception of their interpersonal skills. Lemay *et al*. (2010) presented men and women with photographs of attractive or less attractive individuals and asked them to rate the person's interpersonal skills and how likely they (the participants) were to bond with that person. In two follow-on experiments, they

asked the same of the participants in relation to attractive romantic partners and attractive friends.

They found that the owners of attractive faces were were regarded as interpersonally very receptive. More importantly, participants were more willing to bond with these individuals. This suggests one way in which beautiful people may get their own way: people want to desire them and get to know them.

What is psychology? 9

#### **Established and emerging fields of psychology**

Throughout this book you will encounter many types of psychologist and many types of psychology. As you have already seen, very few individuals call themselves psychologists, rather they describe themselves by their specialism – cognitive psychologist, developmental psychologist, social psychologist, and so on. Before describing and defining each branch of psychology, however, it is important to distinguish between three general terms: psychology, **psychiatry** and **psychoanalysis**. A psychologist normally holds a university degree in a behaviour-related discipline (such as psychology, zoology, cognitive science) and usually possesses a higher research degree (a Ph.D. or doctorate) if they are teaching or a researcher.

Those not researching but working in applied settings such as hospitals or schools may have other, different qualifications that enable them to practise in those environments. Psychiatrists are physicians who have specialised in the causes and treatment of mental disorder. They are medically qualified (unlike psychologists, who nonetheless do study medical problems and undertake biological research) and have the ability to prescribe medication (which psychologists do not). Much of the work done by psychologists in psychiatric settings is similar to that of the psychiatrist, implementing psychological interventions for patients with mental illness. Psychoanalysts are specific types of counsellor who attempt to understand mental disorder by reference to the workings of the unconscious. There is no formal academic qualification necessary to become a psychoanalyst and, as the definition implies, they deal with a limited range of behaviour.

Most research psychologists are employed by colleges or universities, by private organisations or by government. Research psychologists differ from one another in two principal ways: in the types of behaviour they investigate and in the causal events they analyse. That is, they explain different types of behaviour, and they explain them in terms of different types of cause. For example,

two psychologists might both be interested in memory, but they might attempt to explain memory in terms of different causal events – one may focus on physiological events (such as the activation of the brain during memory retrieval) whereas the other may focus on environmental events (such as the effect of noise level on task performance). Professional societies such as the American Psychological Association and the British Psychological Society have numerous subdivisions representing members with an interest in a specific aspect of psychology. This section outlines some of the major branches or subdivisions of psychology. A summary of these can be found in Table 1.1.

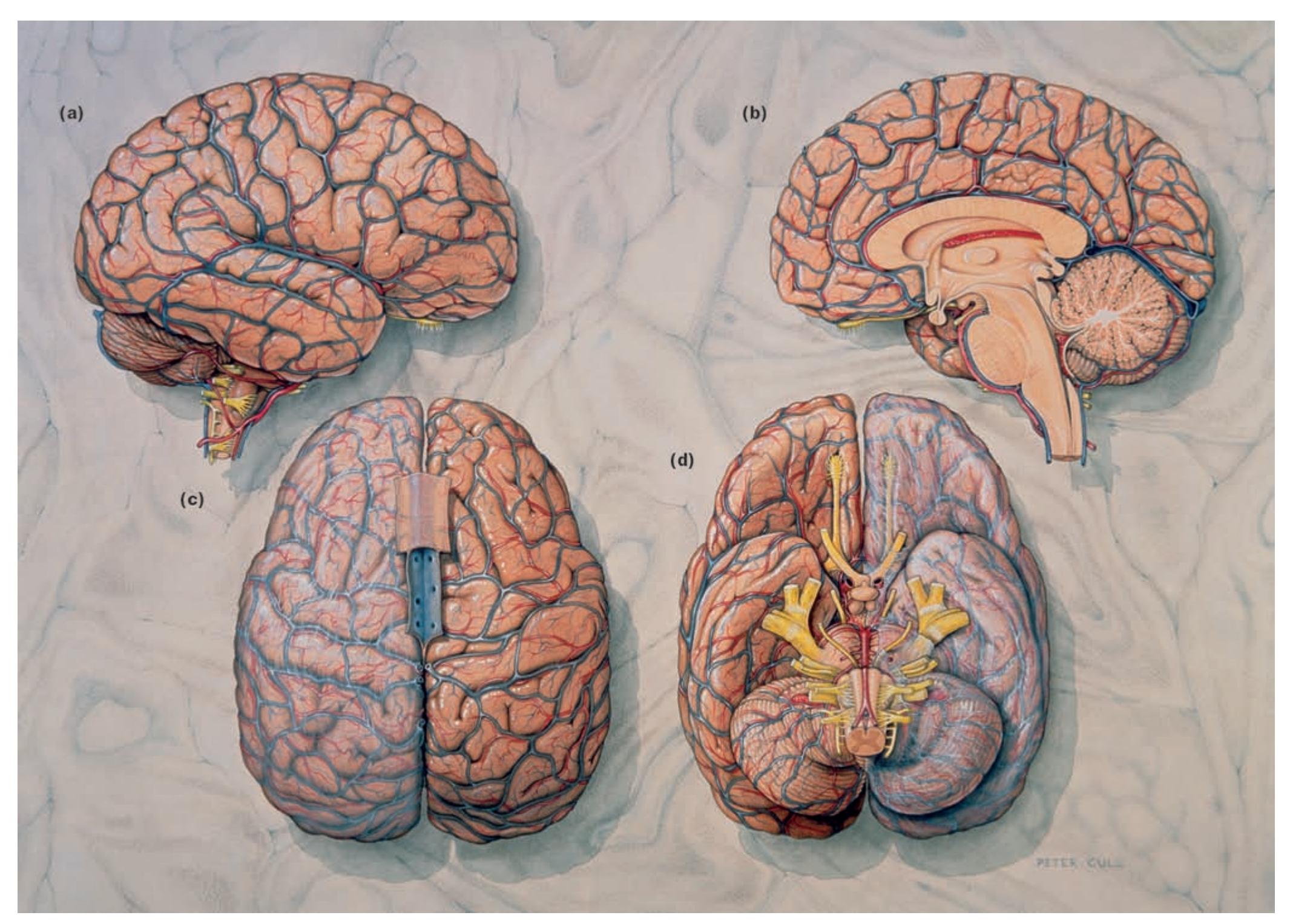

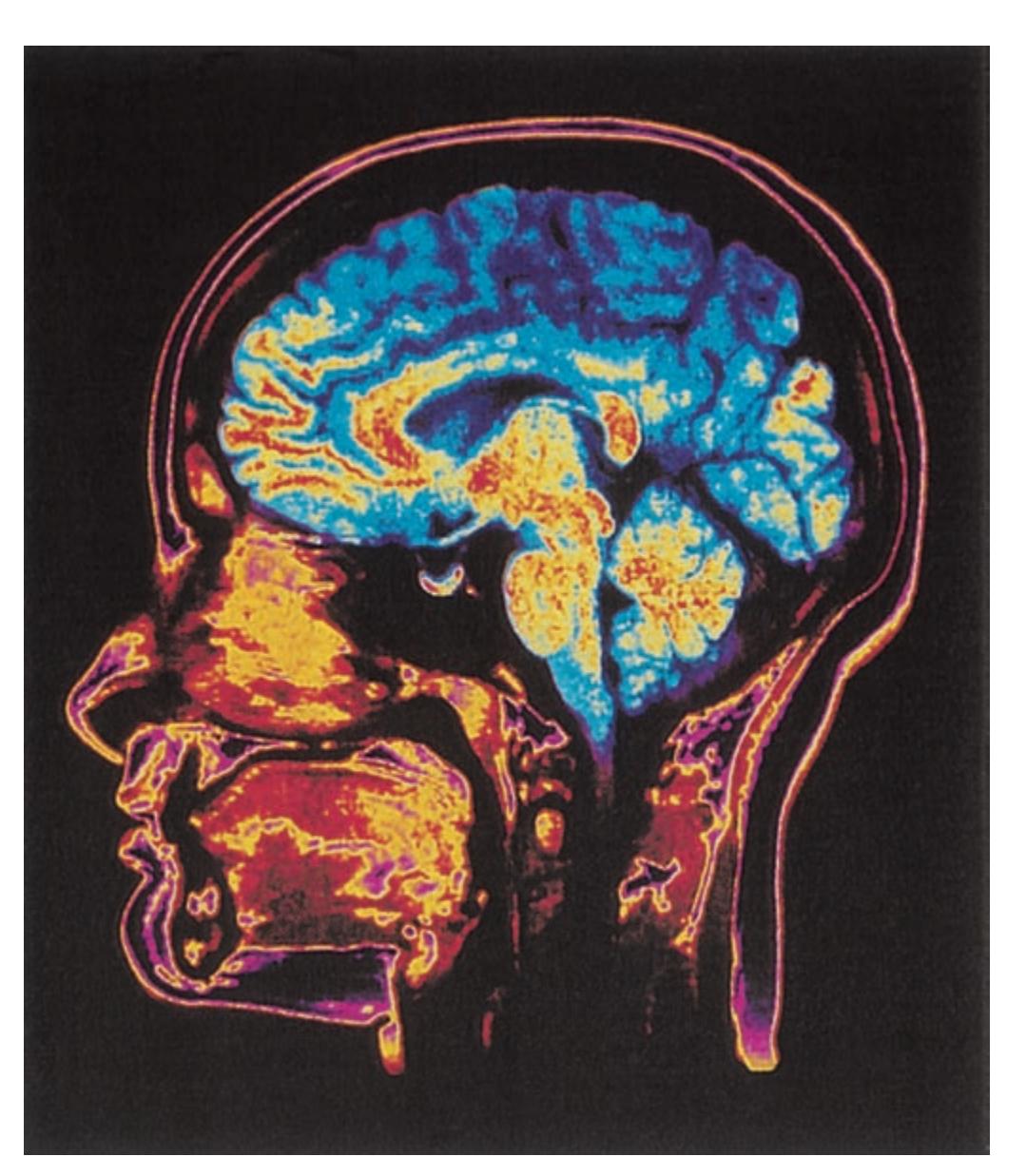

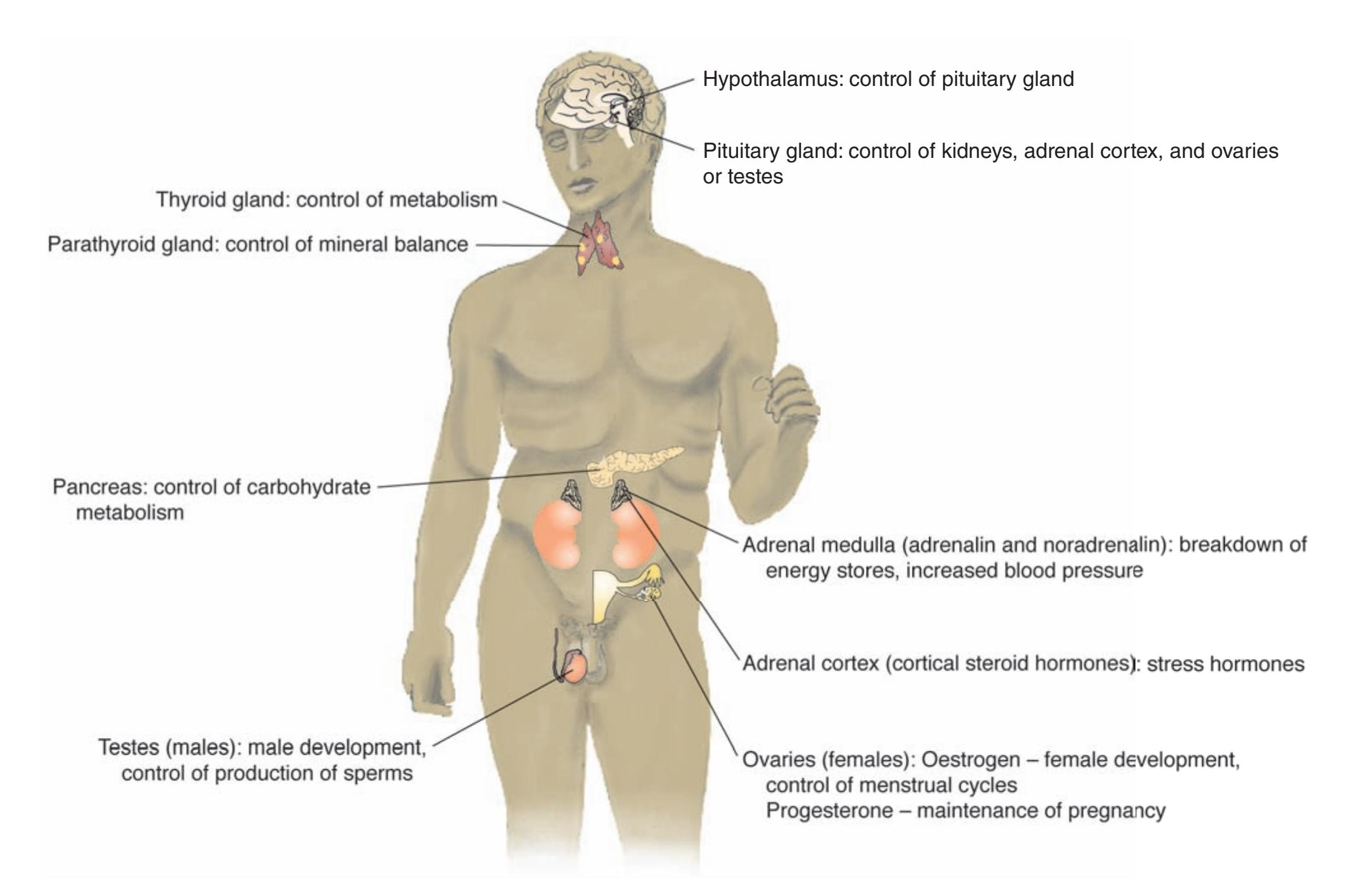

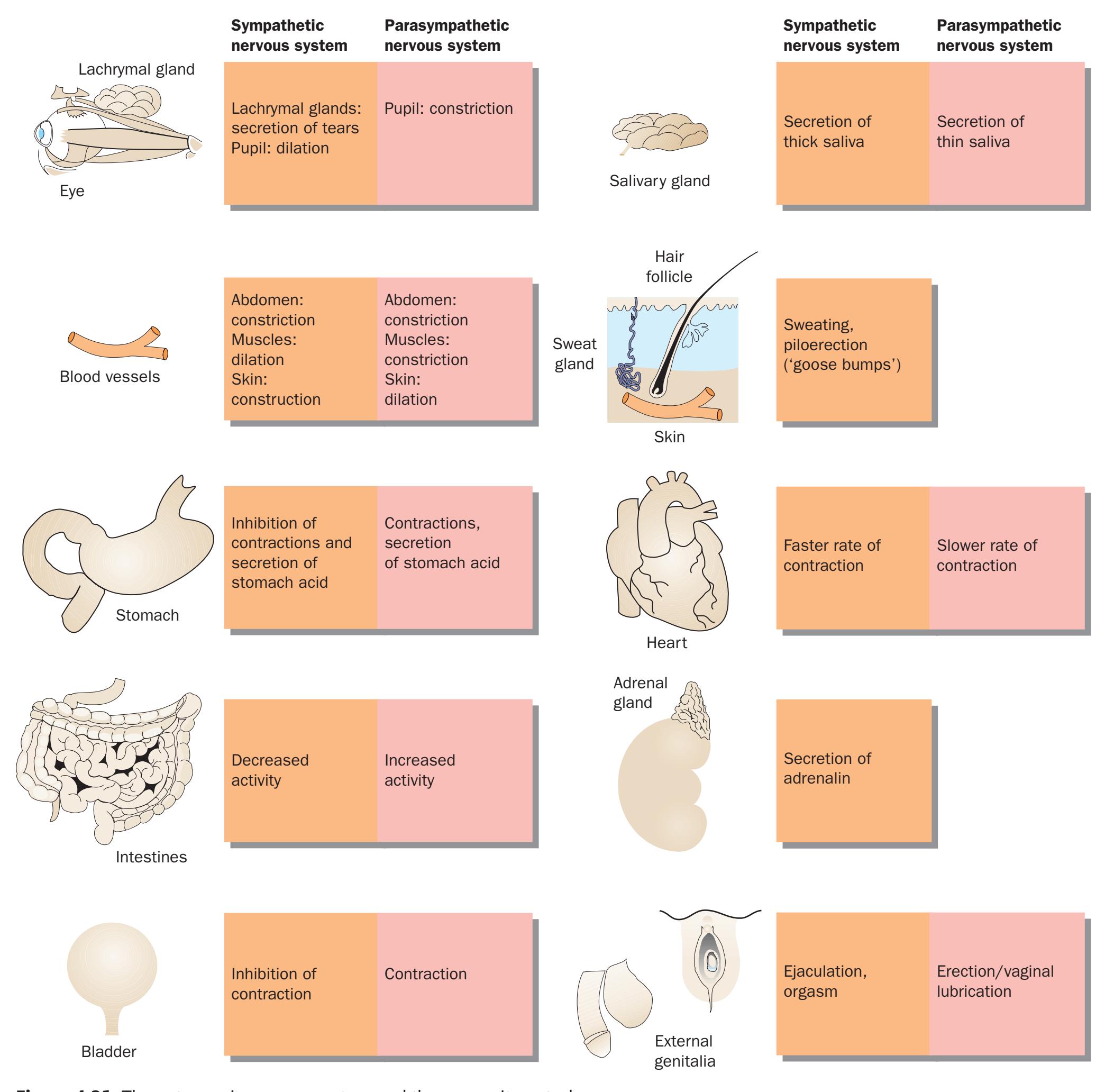

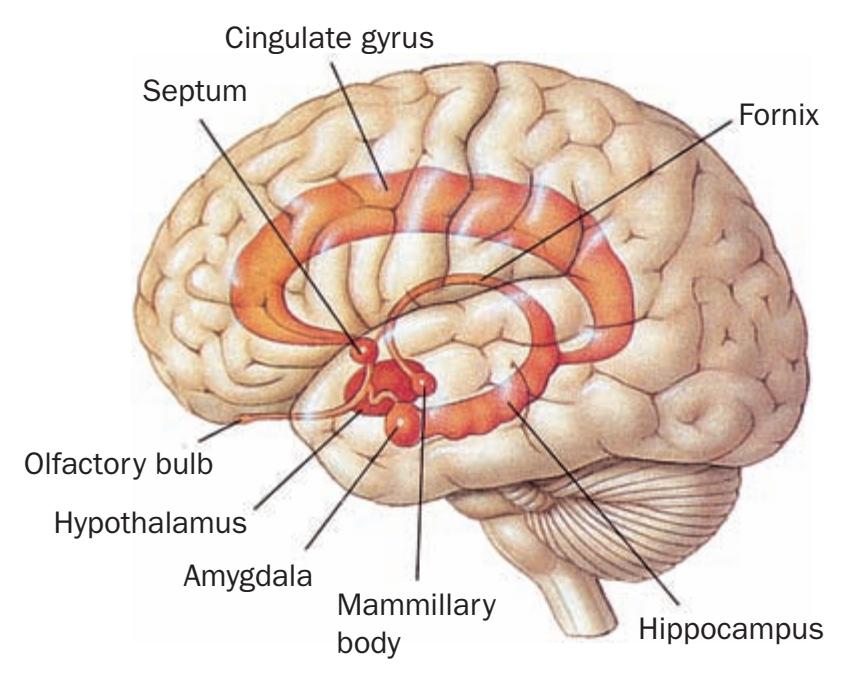

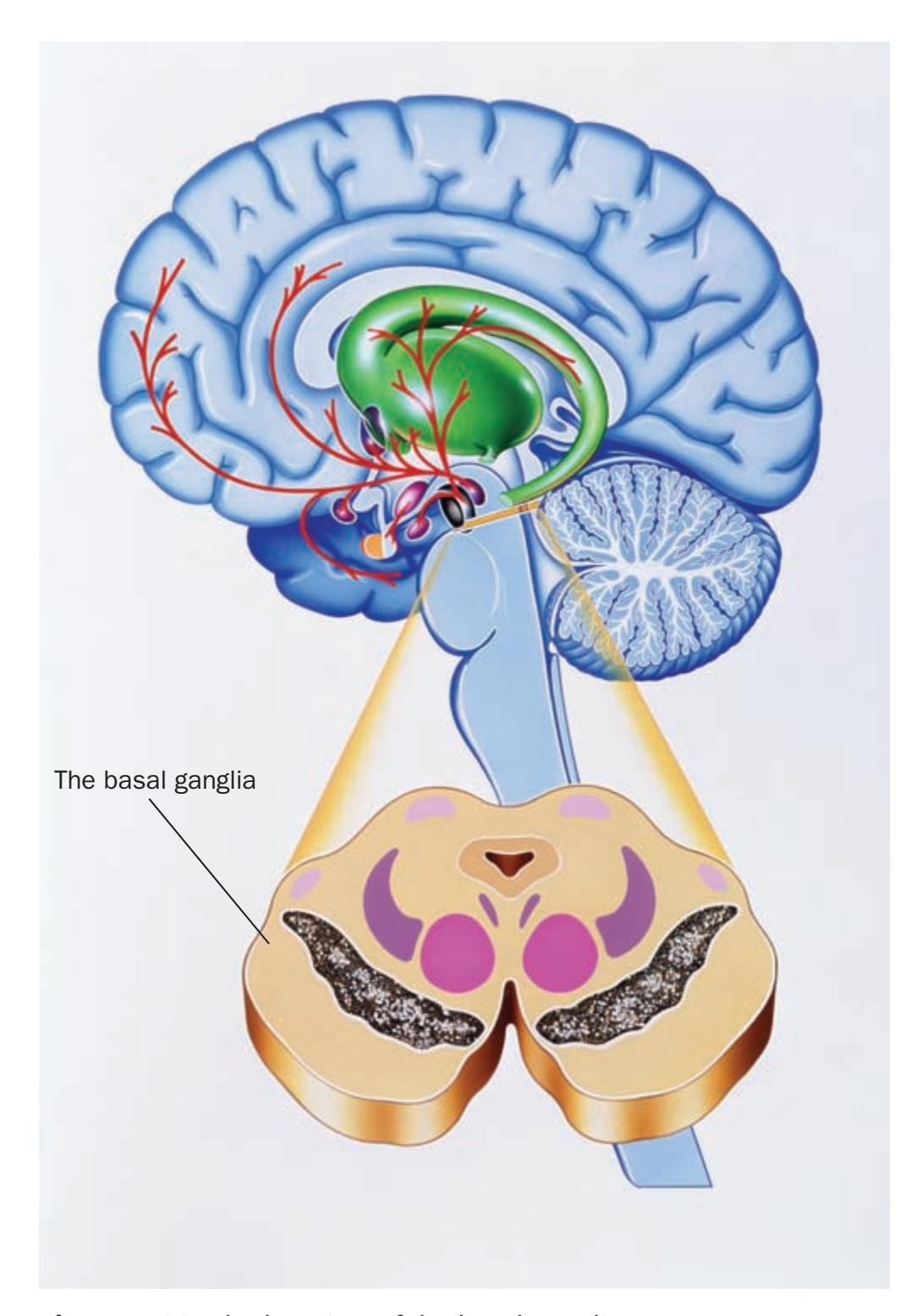

**Psychobiology**/biological psychology is the study of the biological basis of behaviour (G.N. Martin, 2003). Other terms for the same branch include physiological psychology and biopsychology. It investigates the causal events in an organism's physiology, especially in the nervous system and its interaction with glands that secrete hormones. Psychobiologists study almost all behavioural phenomena that can be observed in non-human animals, including learning, memory, sensory processes, emotional behaviour, motivation, sexual behaviour and sleep, using a variety of techniques (see Chapter 4).

**Psychophysiology** is the measurement of people's physiological reactions, such as heart rate, blood pressure, electrical resistance of the skin, muscle tension and electrical activity of the brain (Andreassi, 2007). These measurements provide an indication of a person's degree of arousal or relaxation. Most psychophysiologists investigate phenomena such as sensory and perceptual responses, sleep, stress, thinking, reasoning and emotion.

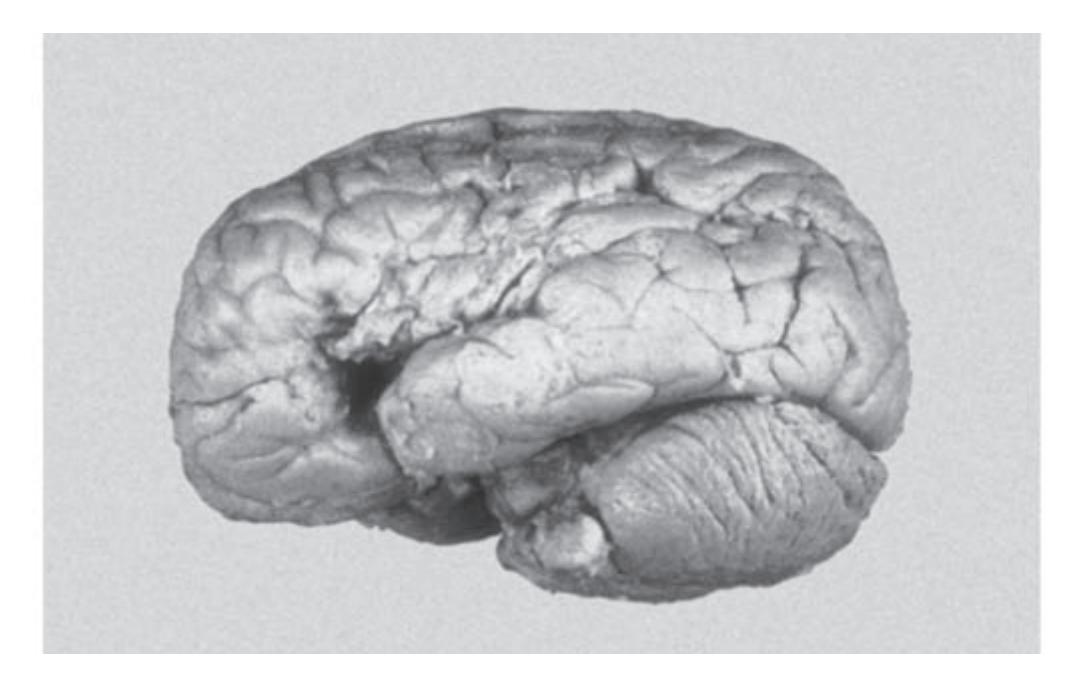

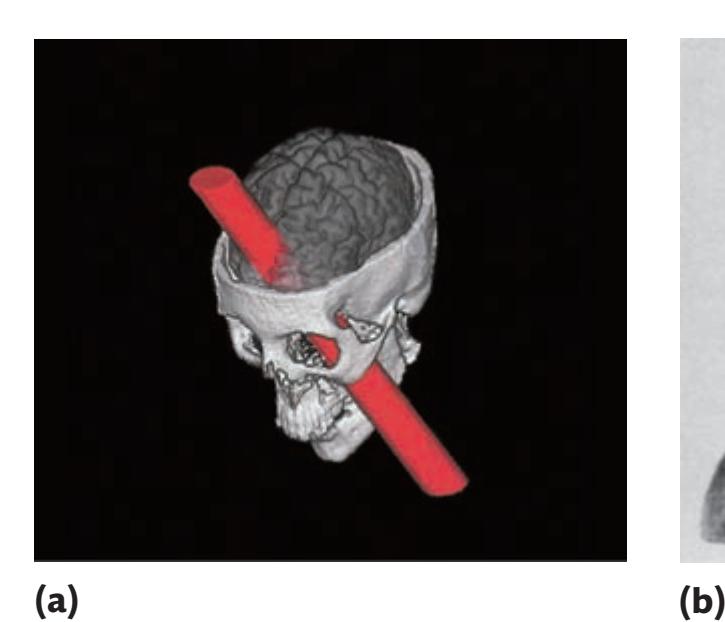

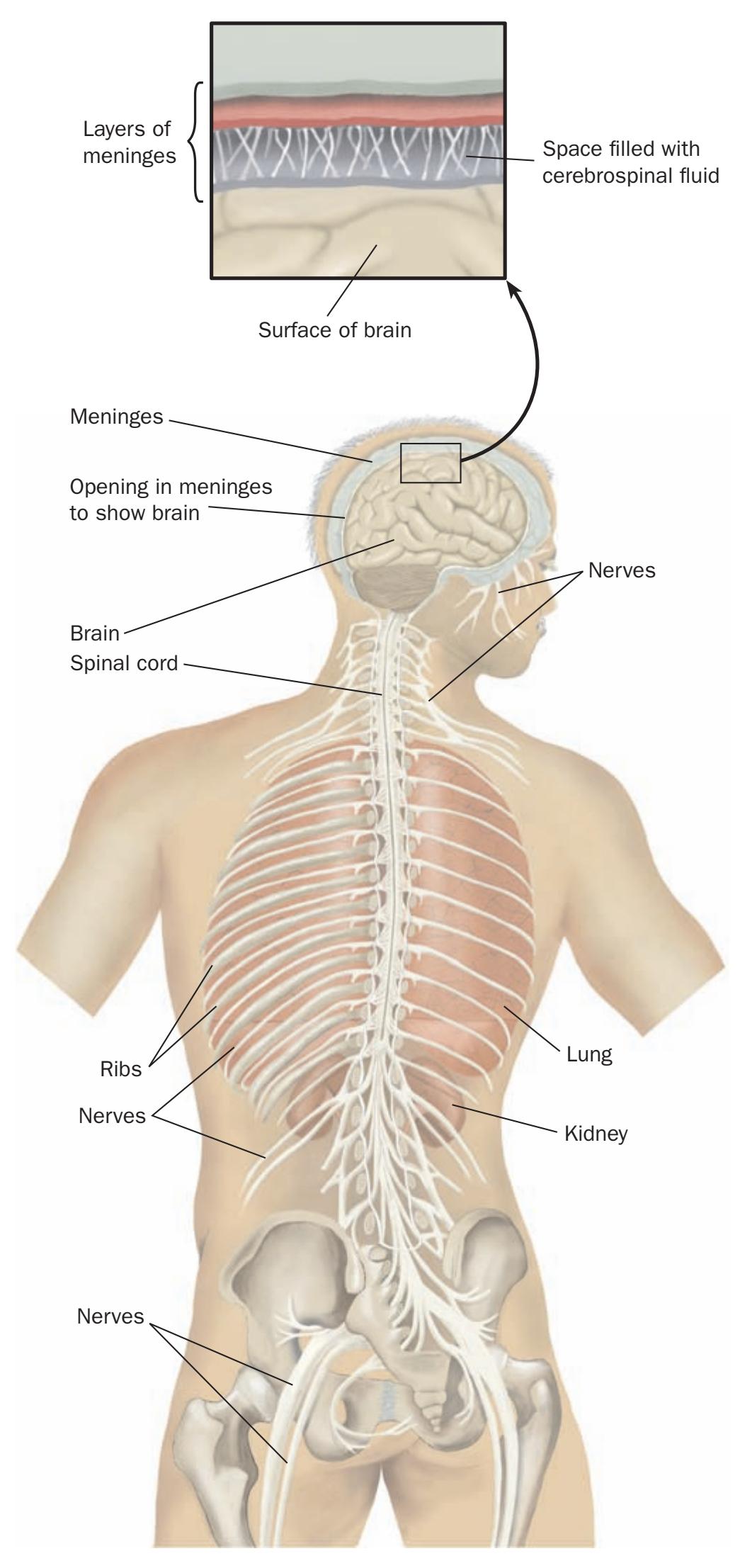

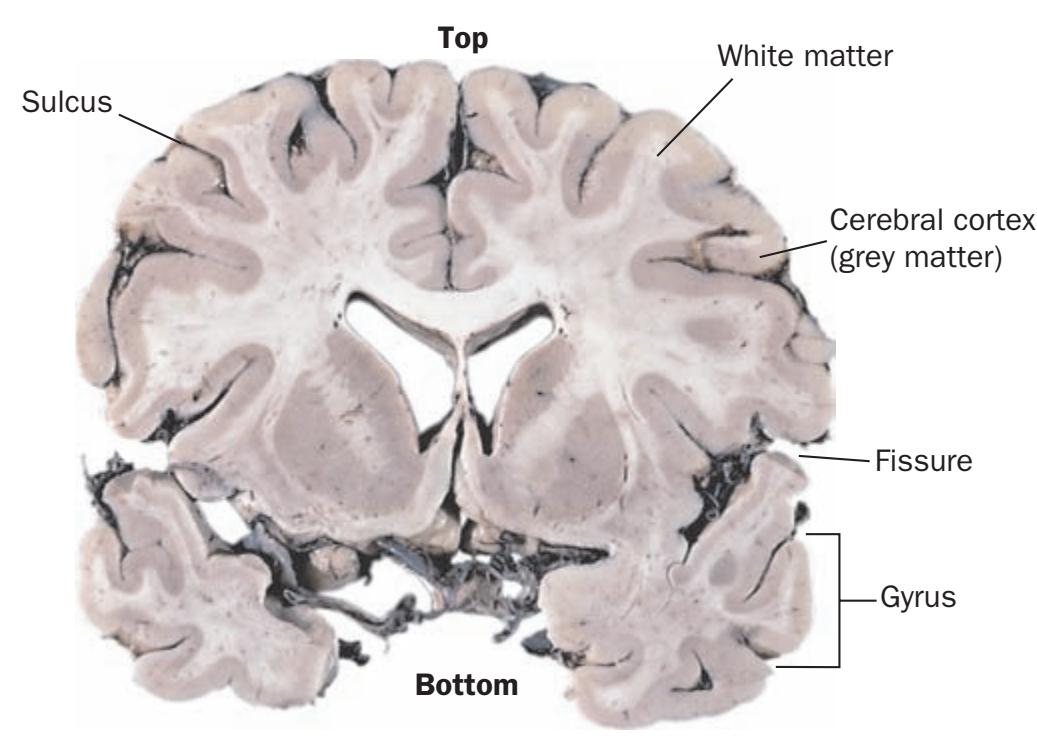

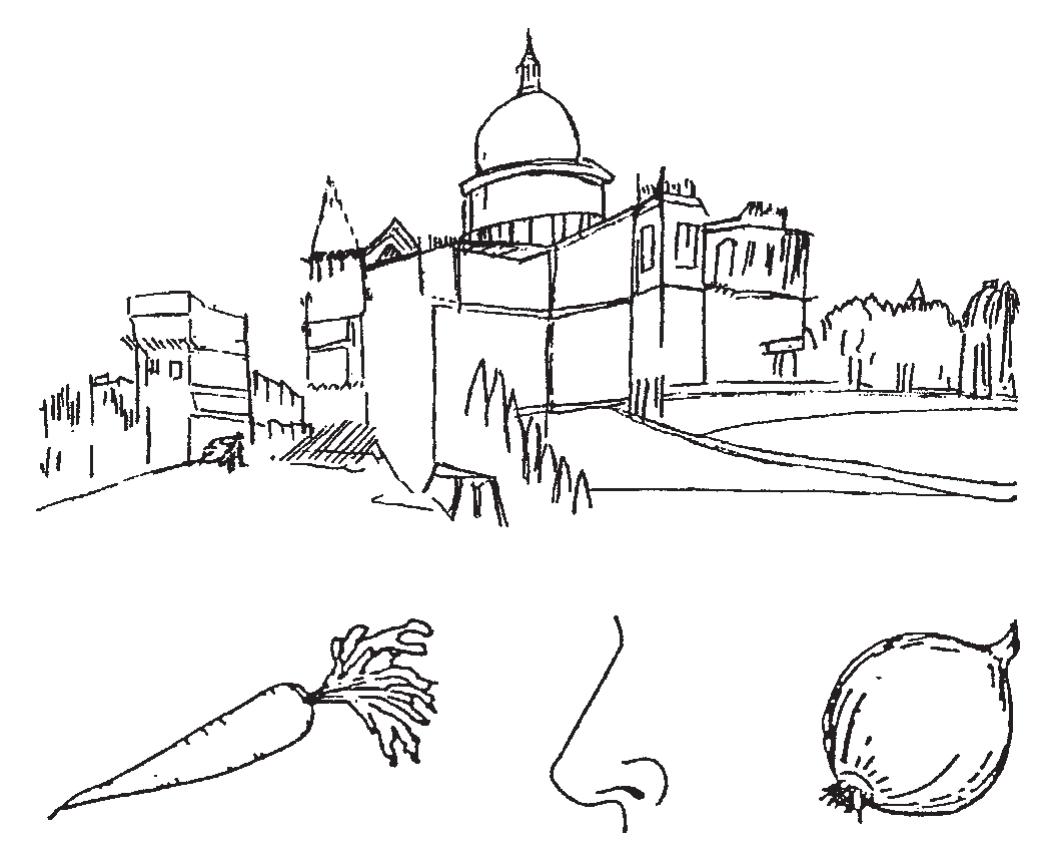

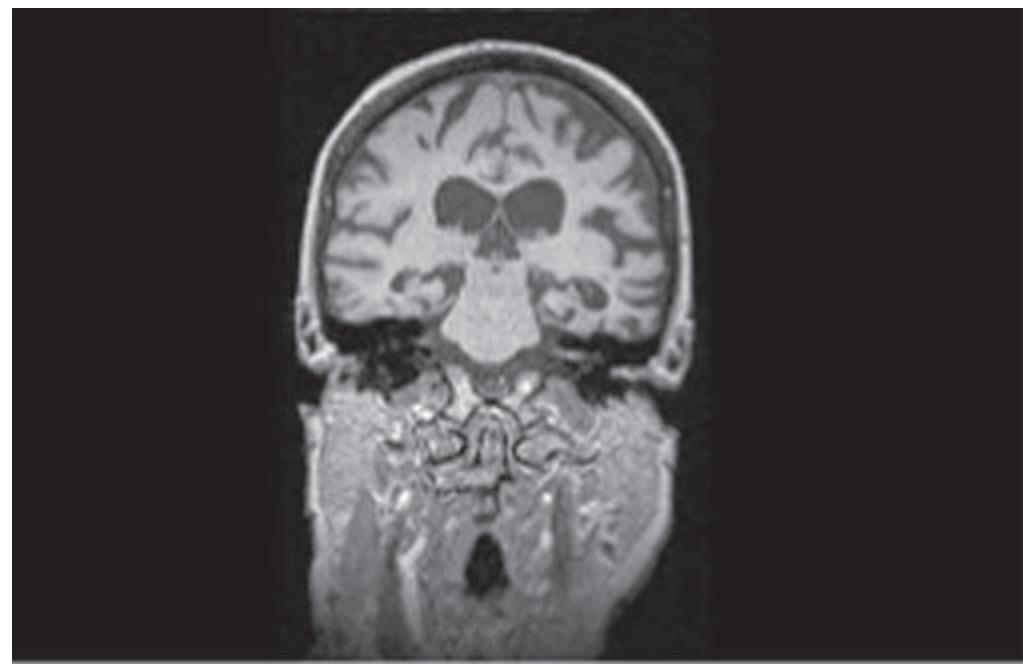

**Neuropsychology** and **neuroscience** examine the relationship between the brain and **spinal cord**, and behaviour (Martin, 2006). Neuropsychology helps to shed light on the role of these structures in movement, vision, hearing, tasting, sleeping, smelling and touching as well as emotion, thinking, language and object recognition and perception, and others. Neuropsychologists normally (but not always) study patients who have suffered injury to the brain – through accident or disease – which disrupts functions such as speech

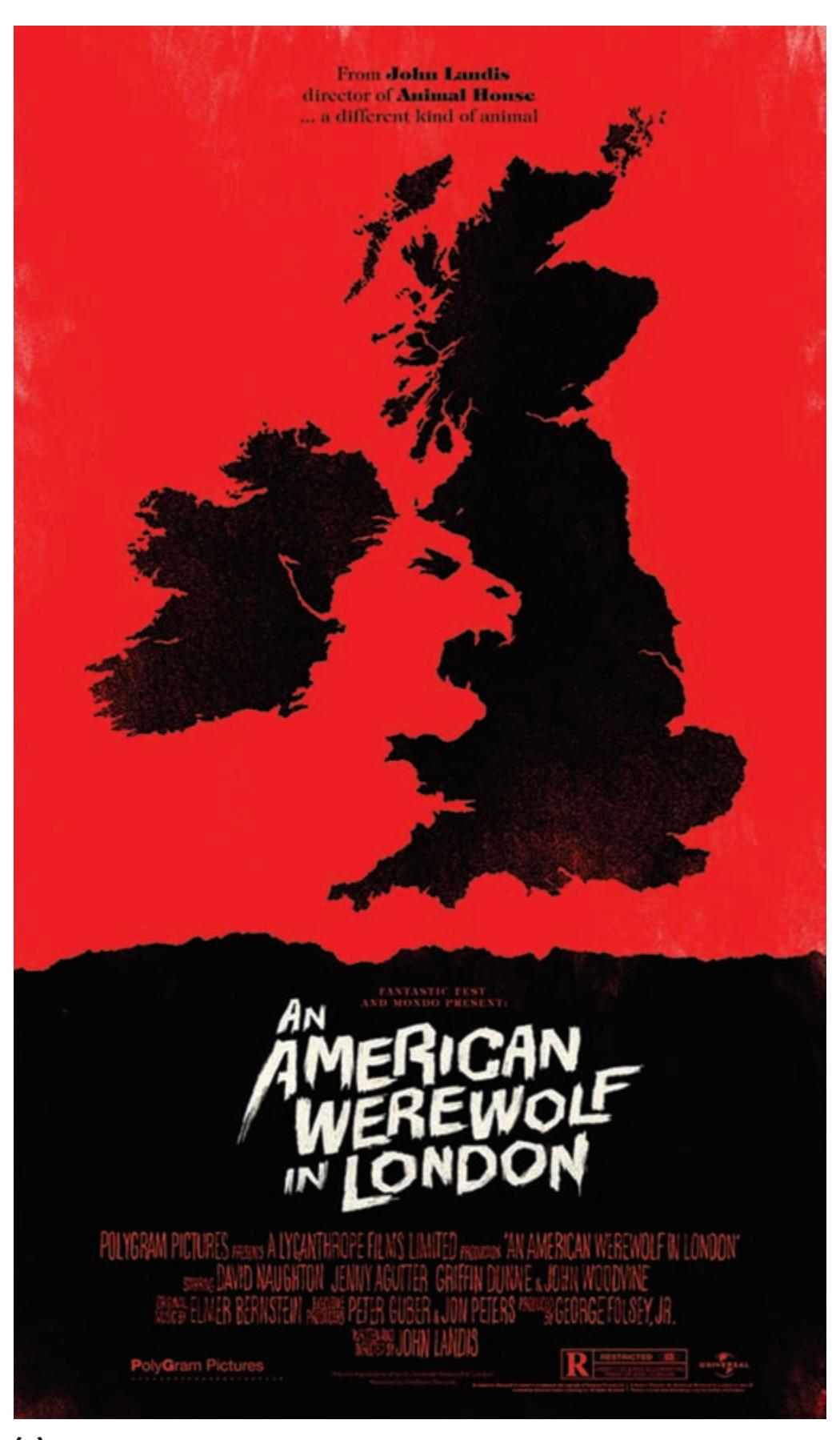

## **Cutting edge:** Darkness and dishonesty

A group of Canadian and US researchers has suggested that darkness can not only produce anonymity for ne'er-do-wells but also provide the illusion of anonymity (Zhong *et al*., 2010). In a series of experiments, people were more likely to cheat and accrue more unearned money when they were in a slightly dimmed room than in a well-lit room. They also found that people who wore sunglasses behaved more selfishly than did those who wore clear glasses. Anonymity was a key mediator: those who thought that they were more anonymous behaved more dishonestly and selfishly.

▼

10 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

## **Cutting edge:** *Continued*

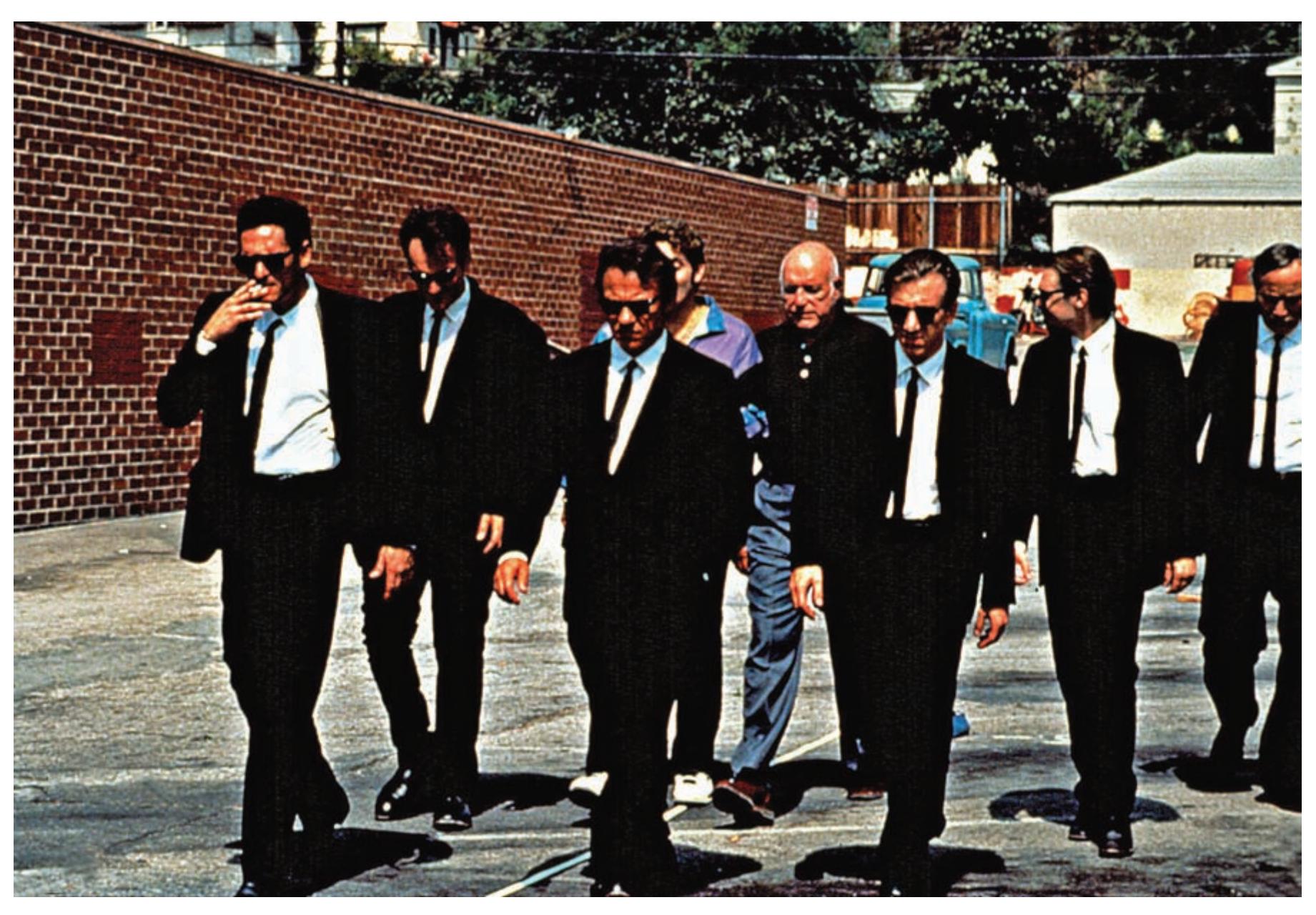

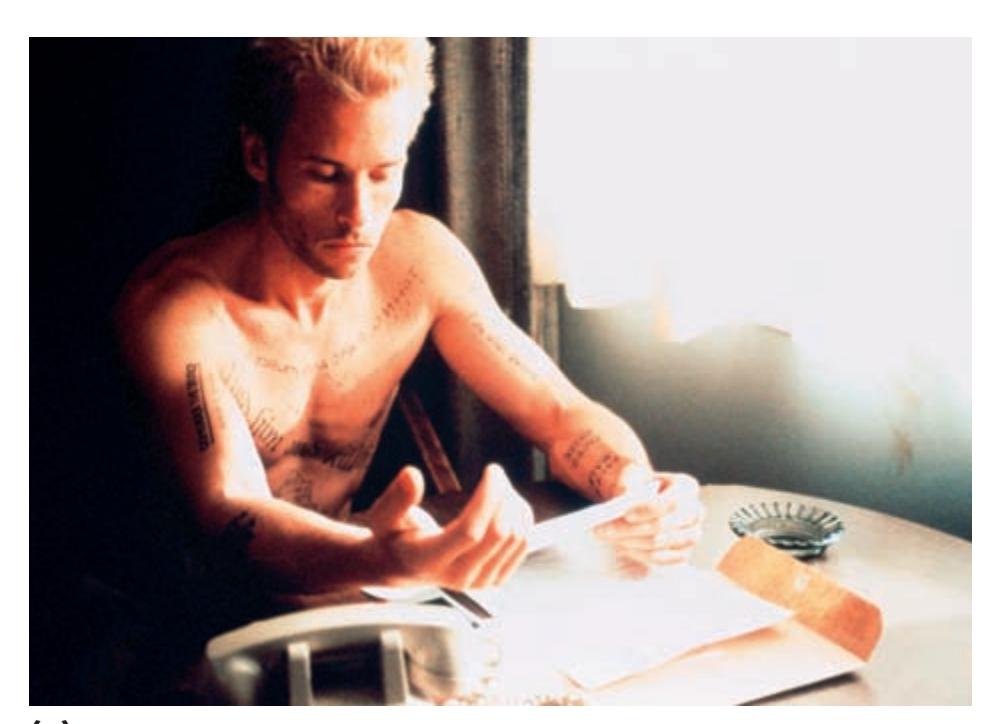

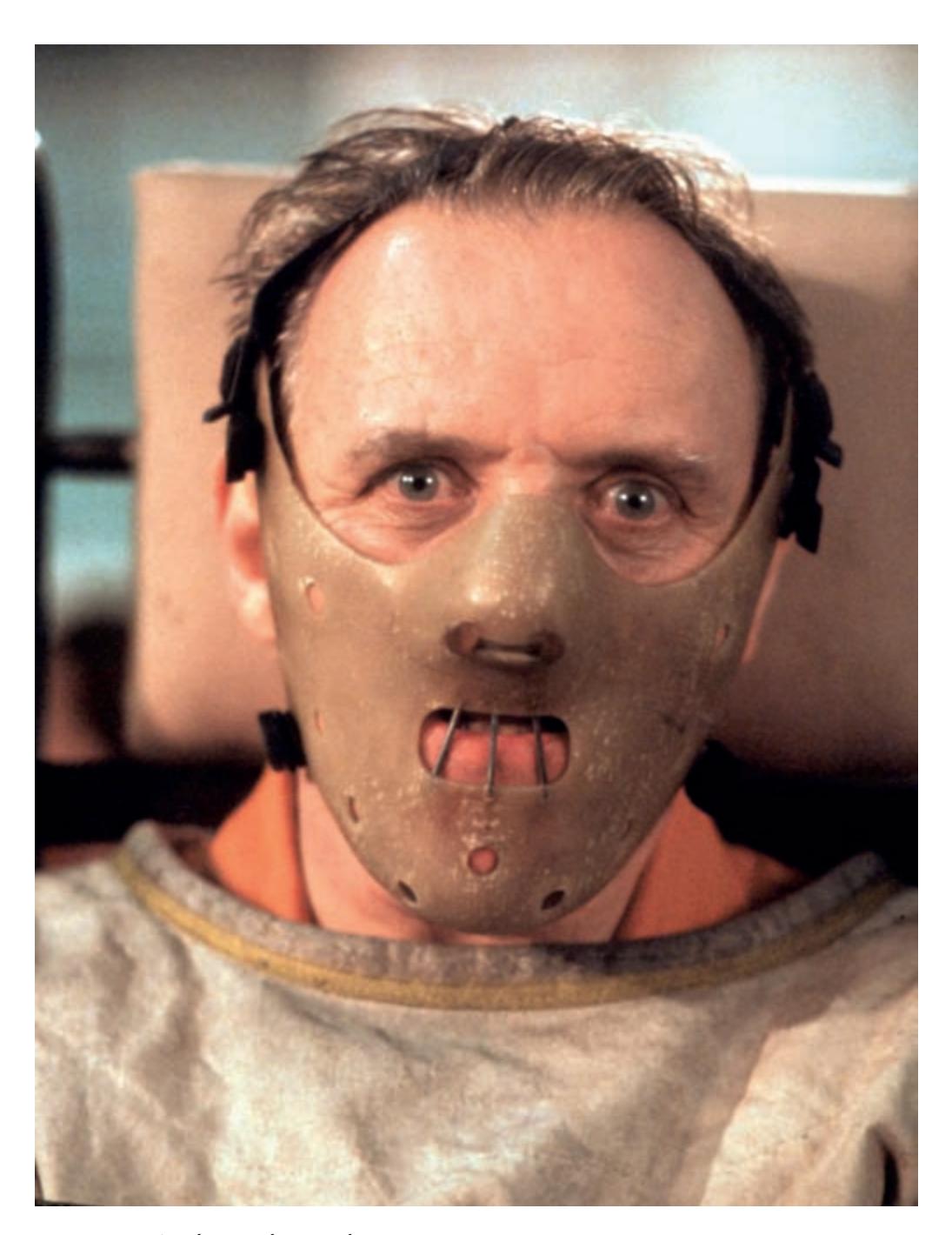

Utterly untrustworthy (see Zhong *et al*., 2010). *Source*: Rex Features: Miramax/Everett.

production or comprehension, object recognition, visual or auditory perception, and so on. **Clinical neuropsychology** involves the study of the effect of brain injury on behaviour and function.

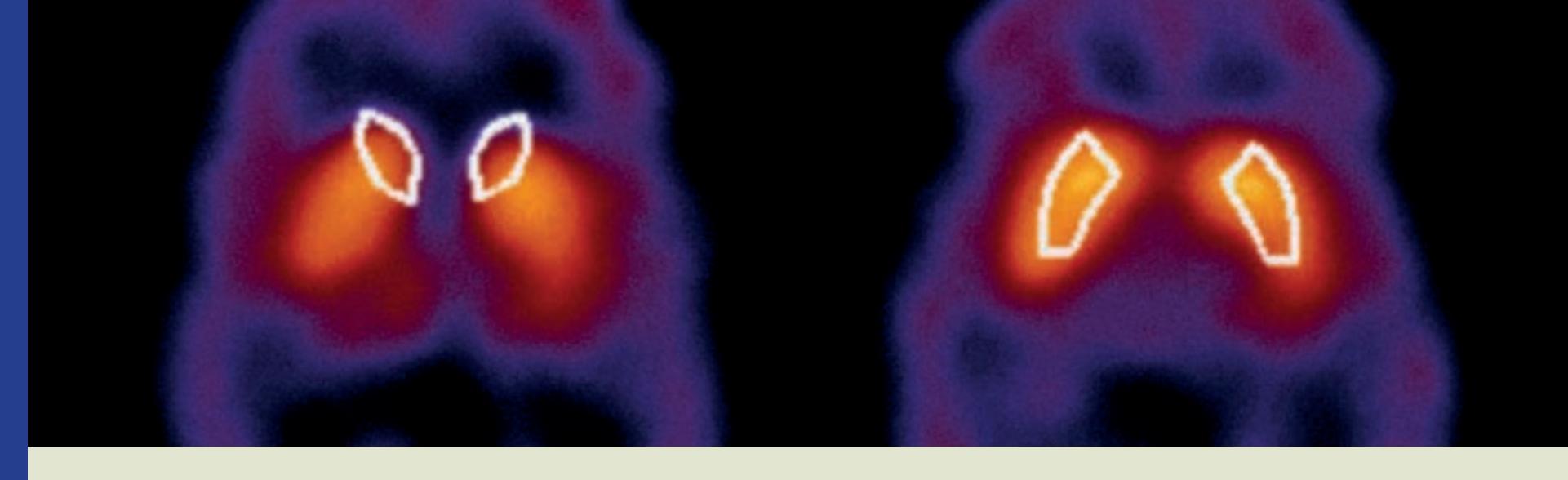

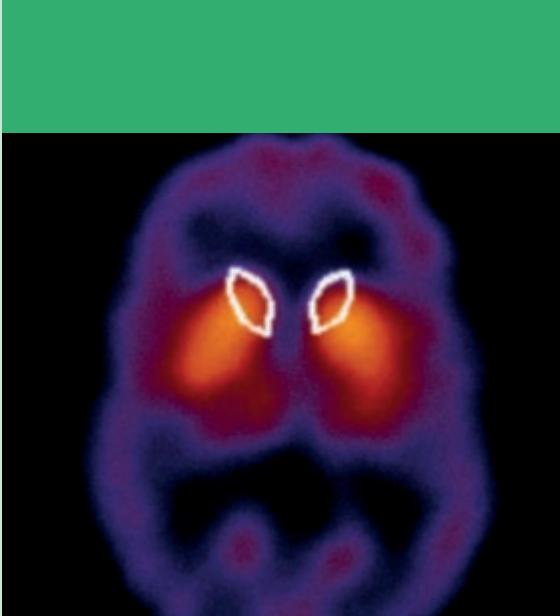

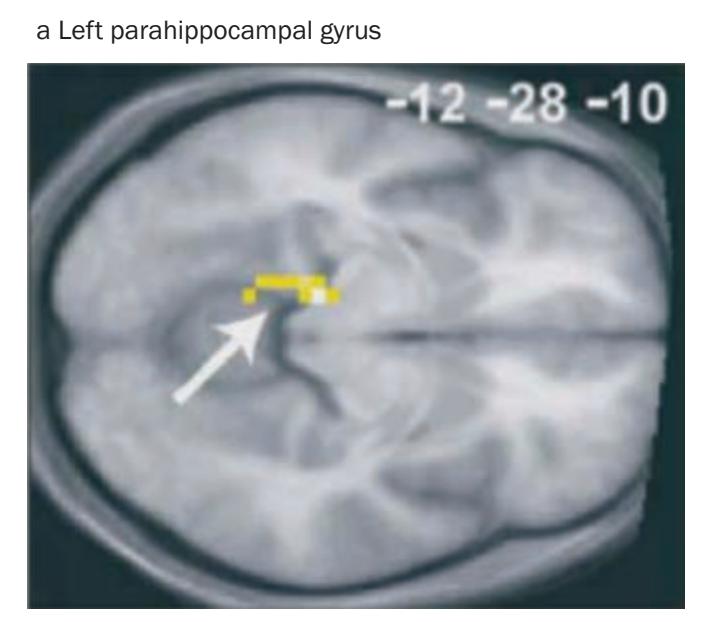

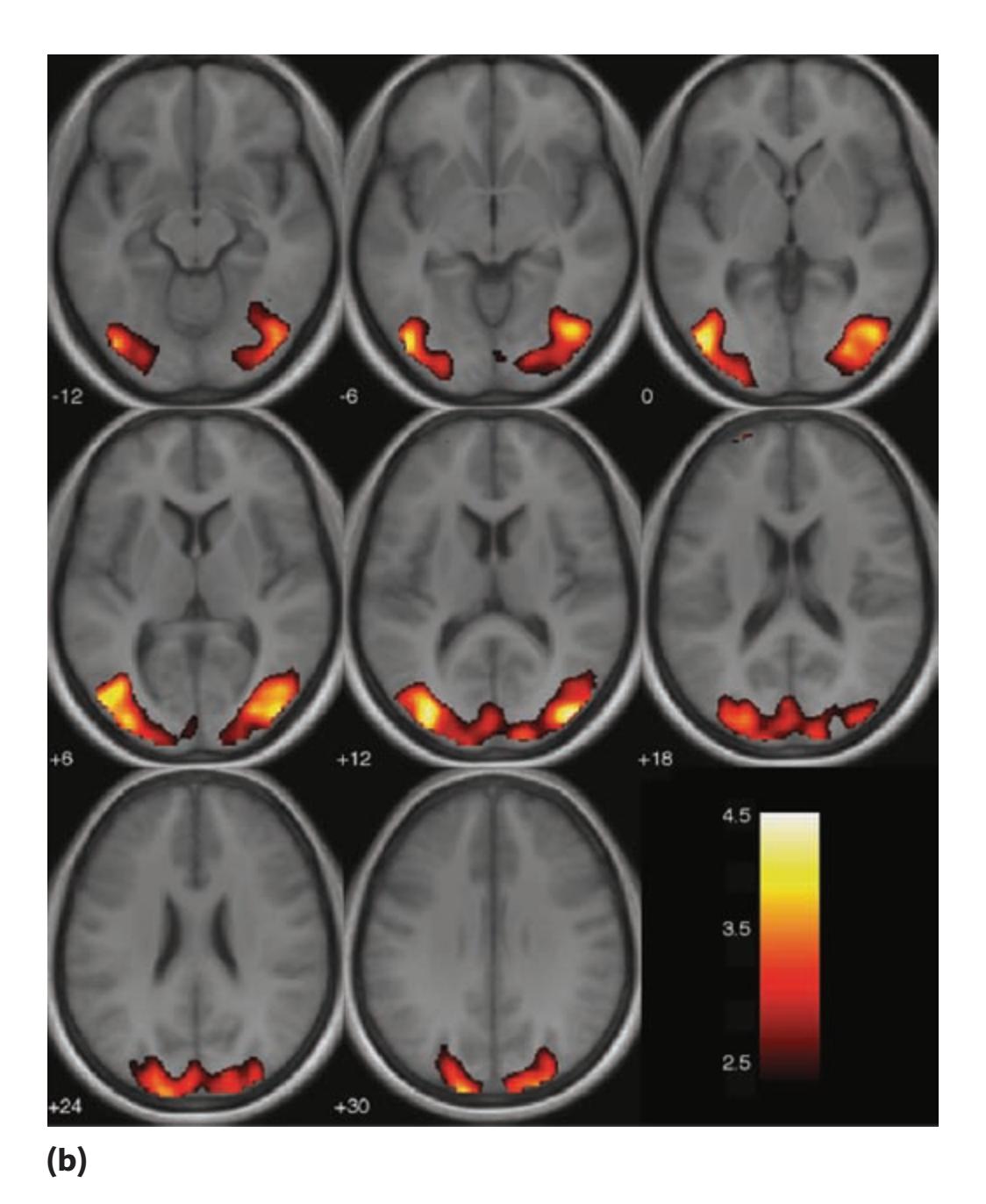

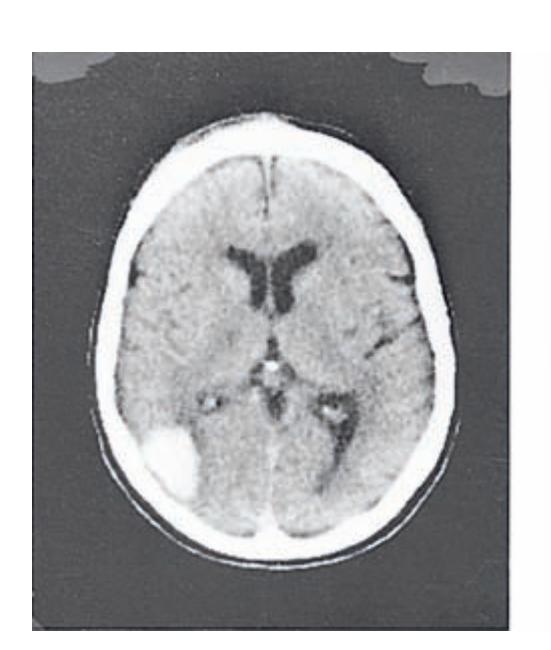

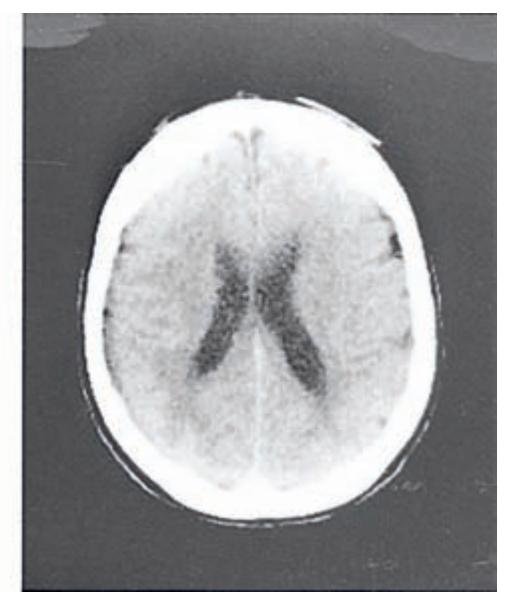

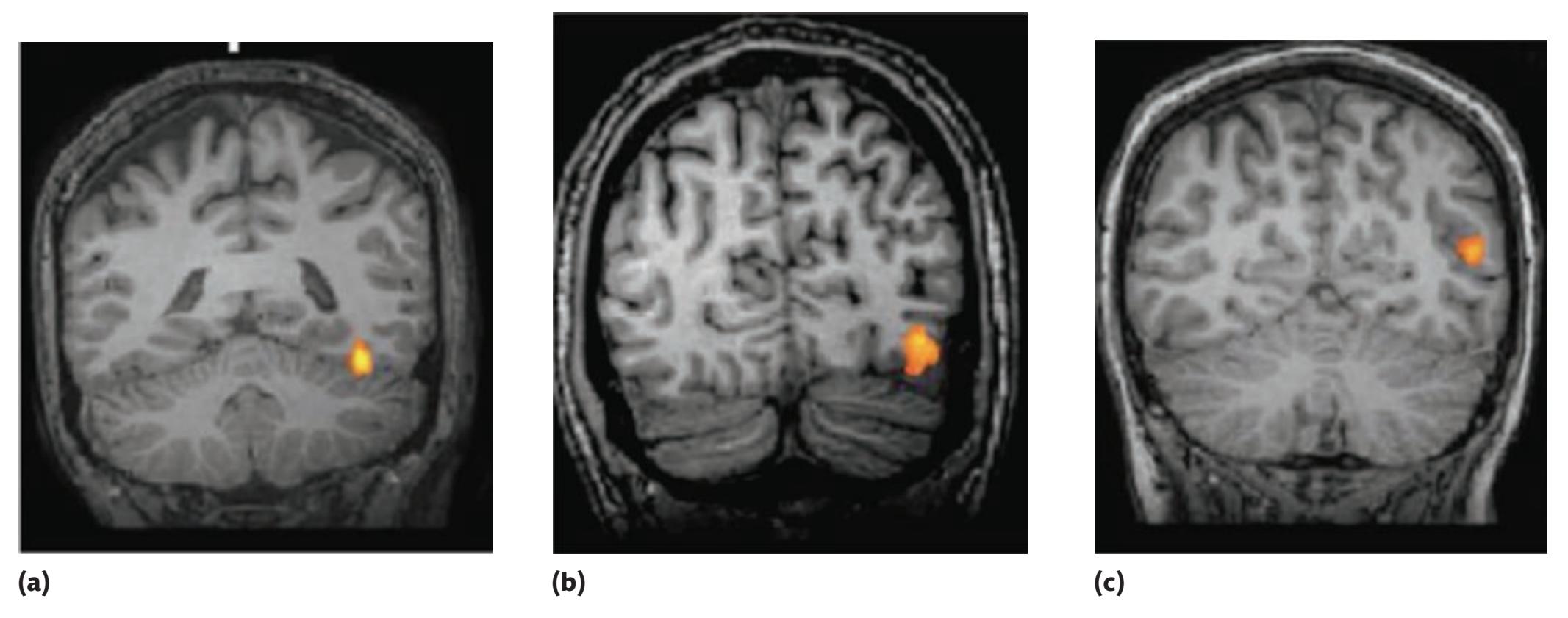

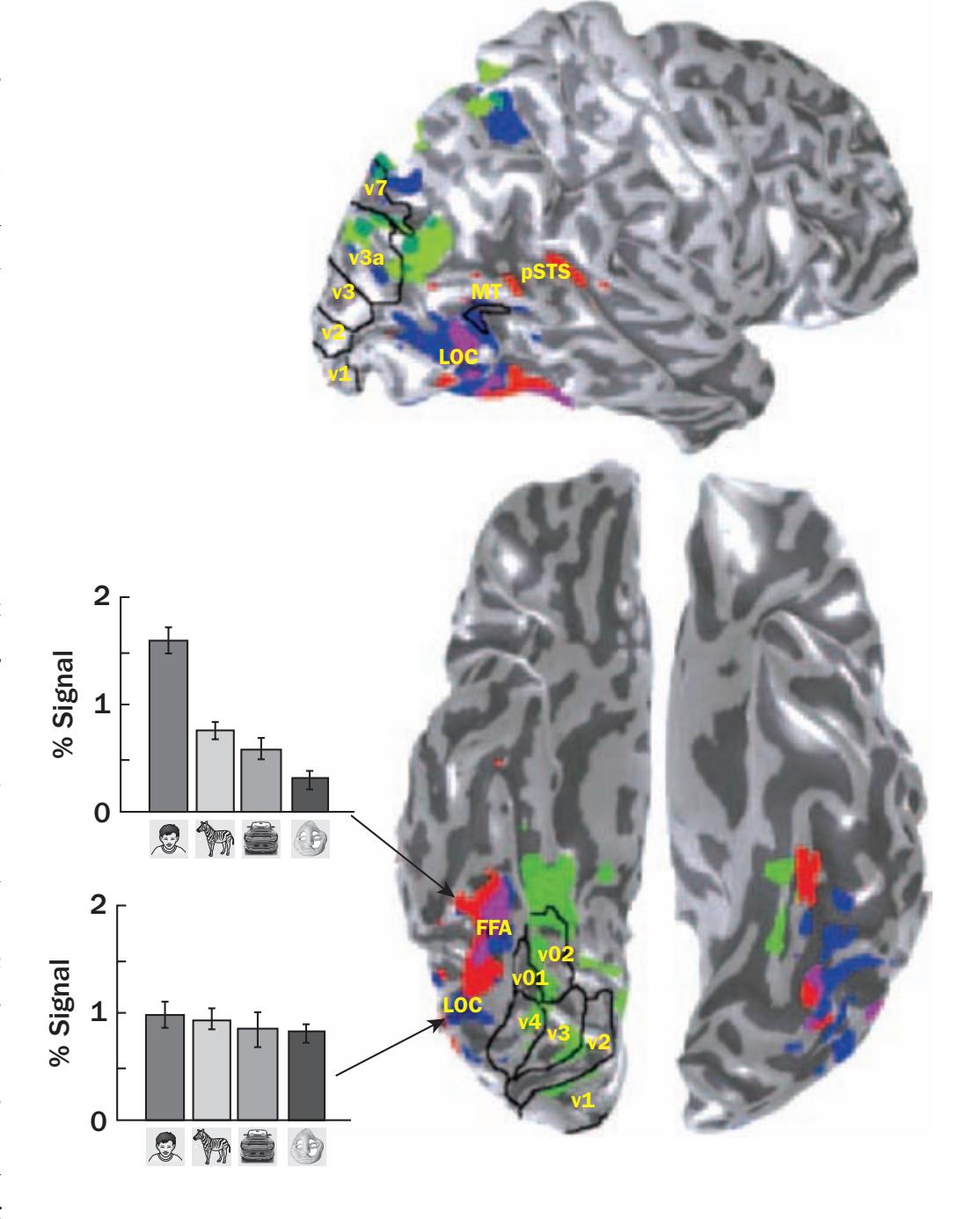

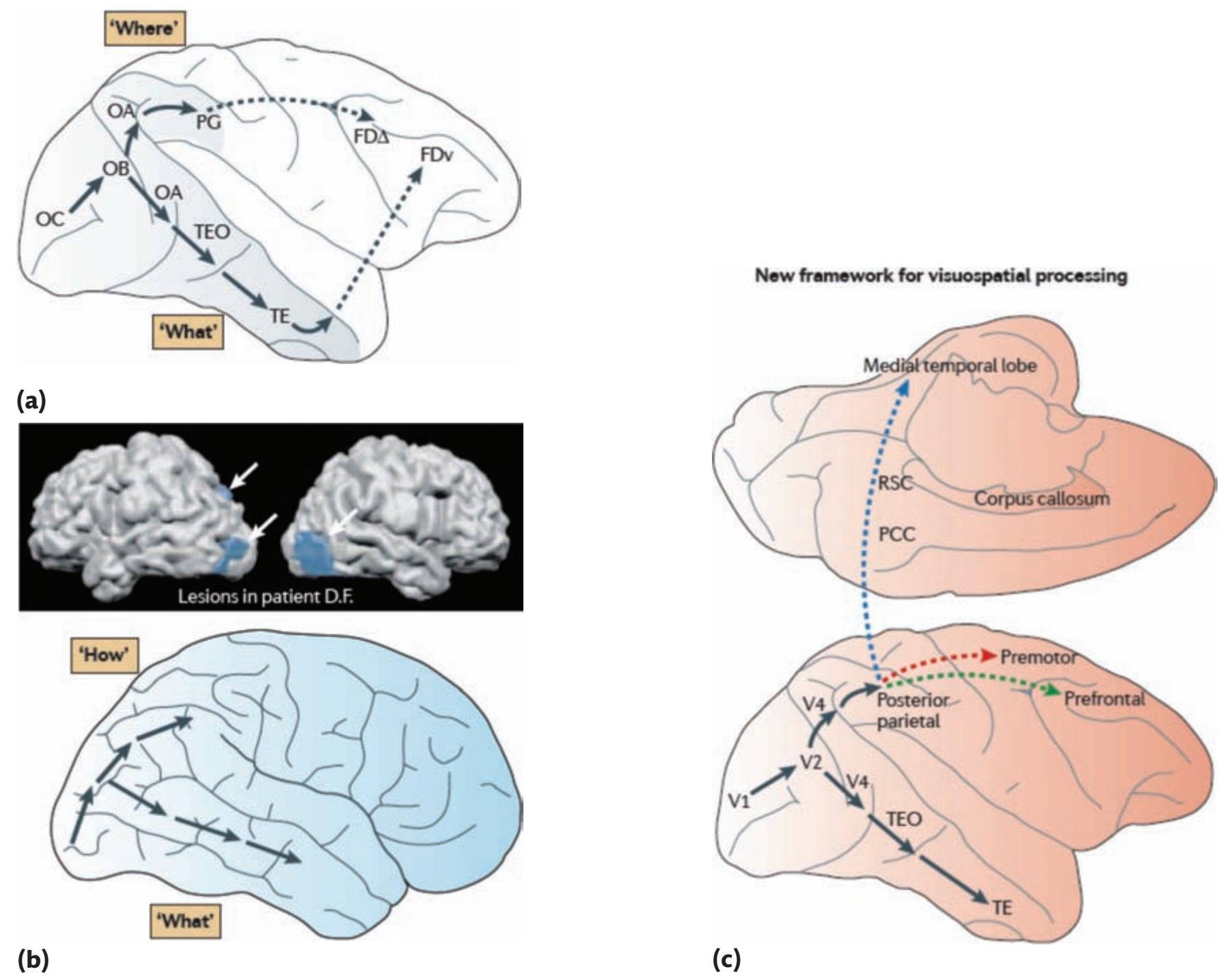

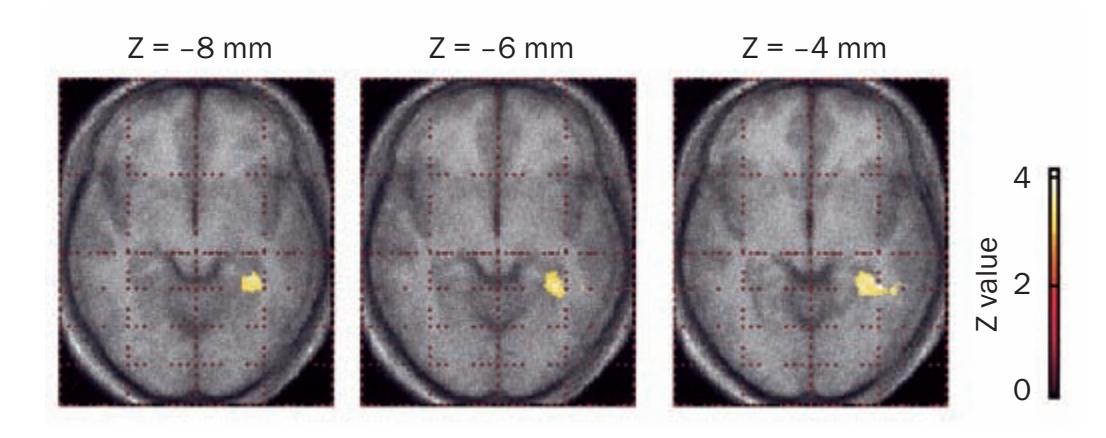

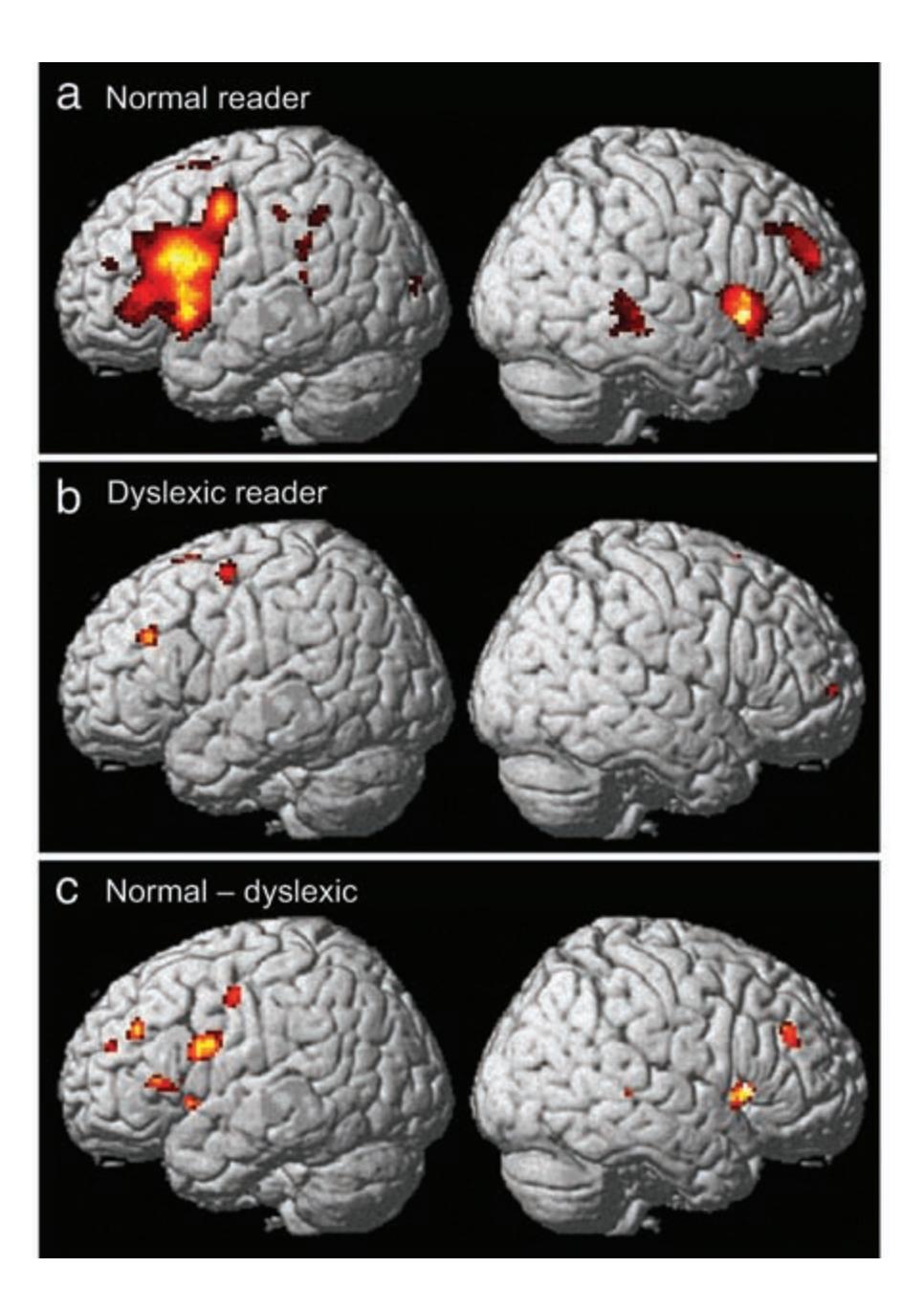

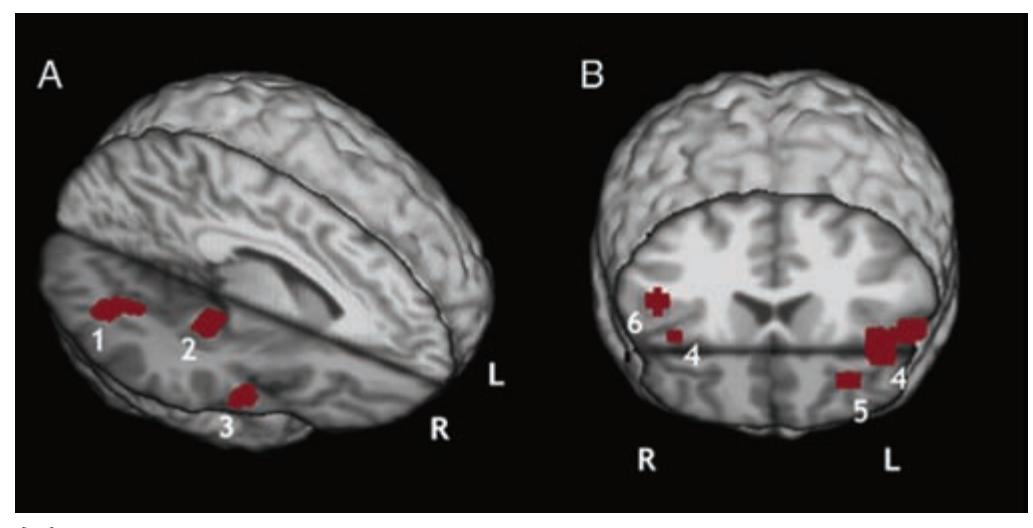

Modern neuropsychology also relies on sophisticated brain imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) which allow researchers to monitor the activity of processes in the brain as some psychological task is performed. This approach combines two approaches in psychology: neuroscience and cognitive psychology (see below). Because of this, the area of study is sometimes described as **cognitive neuroscience** (Gazzaniga, 1995) or behavioural neuroscience. A new development in this area has been the study of the psychobiological processes involved in social behaviour, a sub-branch called social neuroscience. Social neuroscientists examine the role of the brain in behaviours such as empathy, turn-taking, seeing things from another person's point of view, social interaction, political outlook, and so on. We look at the work of cognitive/behavioural/social

neuroscientists in more detail throughout this text (see in particular Chapter 4).

**Comparative psychology** is the study of the behaviour of members of a variety of species in an attempt to explain behaviour in terms of evolutionary adaptation to the environment. Comparative psychologists study behavioural phenomena similar to those studied by physiological psychologists. They are more likely than most other psychologists to study inherited behavioural patterns, such as courting and mating, predation and aggression, defensive behaviours and parental behaviours.

Closely tied to comparative psychology is **ethology**, the study of the biological basis of behaviour in the context of the evolution of development and function. Ethologists usually make their observations based on studies of animal behaviour in natural conditions and investigate topics such as instinct, social and sexual behaviour and cooperation. A sub-discipline of ethology is **sociobiology** which attempts to explain social behaviour in terms of biological inheritance and evolution. Ethology and What is psychology? 11

sociobiology are described in more detail in Chapter 3. Evolutionary psychology studies 'human behaviour as a the product of evolved psychological mechanisms that depend on internal and environmental input for their development, activation, and expression in manifest behaviour' (Confer *et al*., 2010, p. 110) (see Chapter 3). Although the basis of evolutionary psychology is found in the work of Charles Darwin (described in Chapter 3 and briefly below), as a sub-discipline it is relatively young having developed in the past 15 years.

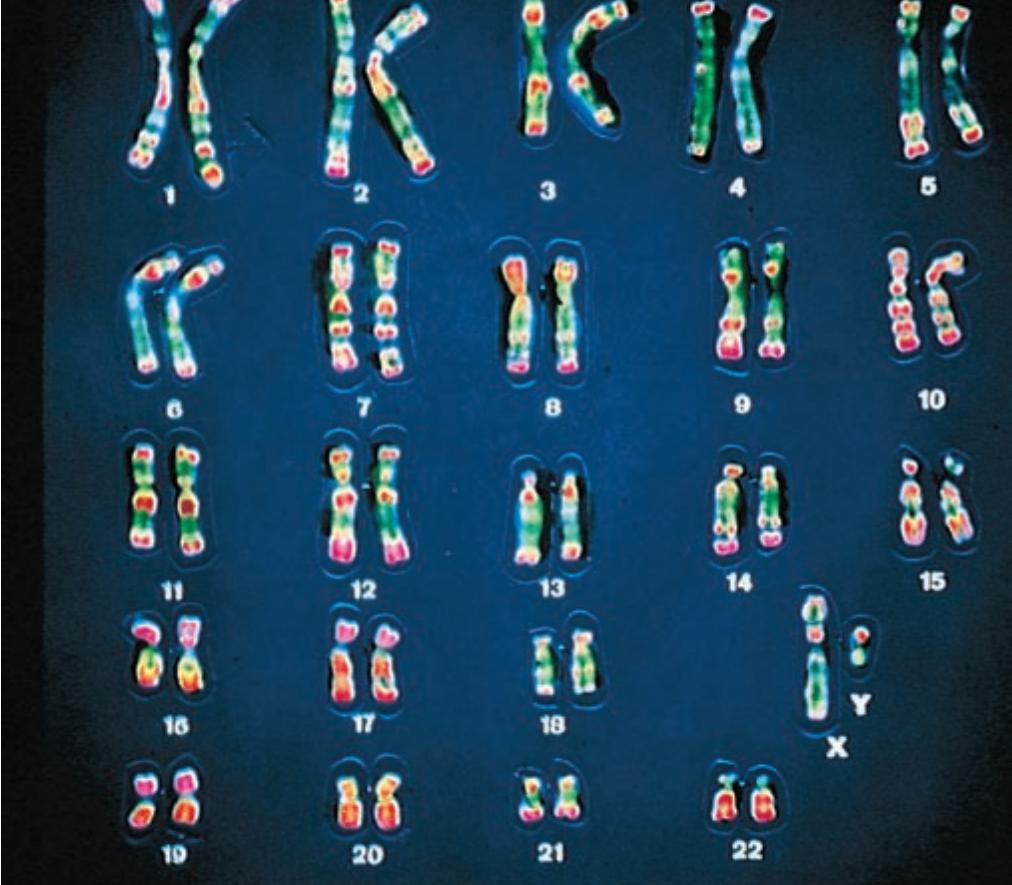

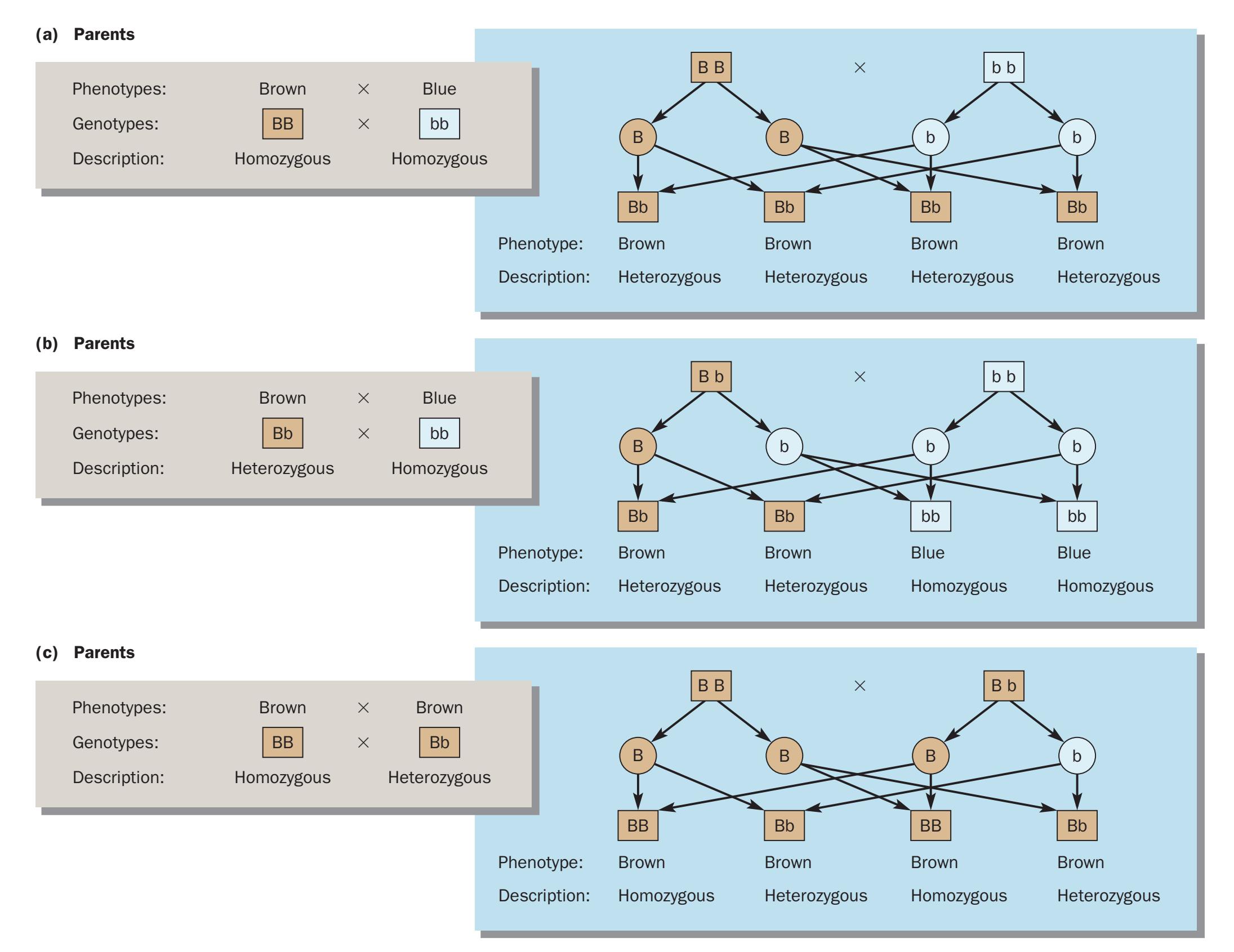

**Behaviour genetics** is the branch of psychology that studies the role of genetics in behaviour (Plomin, 2008). The genes we inherit from our parents include a blueprint for the construction of a human brain. Each blueprint is a little different, which means that no two brains are exactly alike. Therefore, no two people will act exactly alike, even in an identical situation. Behaviour geneticists study the role of genetics in behaviour by examining similarities in physical and behavioural characteristics of blood relatives, whose genes are more similar than those of unrelated individuals. They also perform breeding experiments with laboratory animals to see what aspects of behaviour can be transmitted to an animal's offspring. Behavioural geneticists study the degree to which genetics are responsible for specific behaviours such as cognitive

ability. The work of behavioural geneticists is described in Chapter 3 and discussed in the context of intelligence research and personality in Chapters 11 and 14.

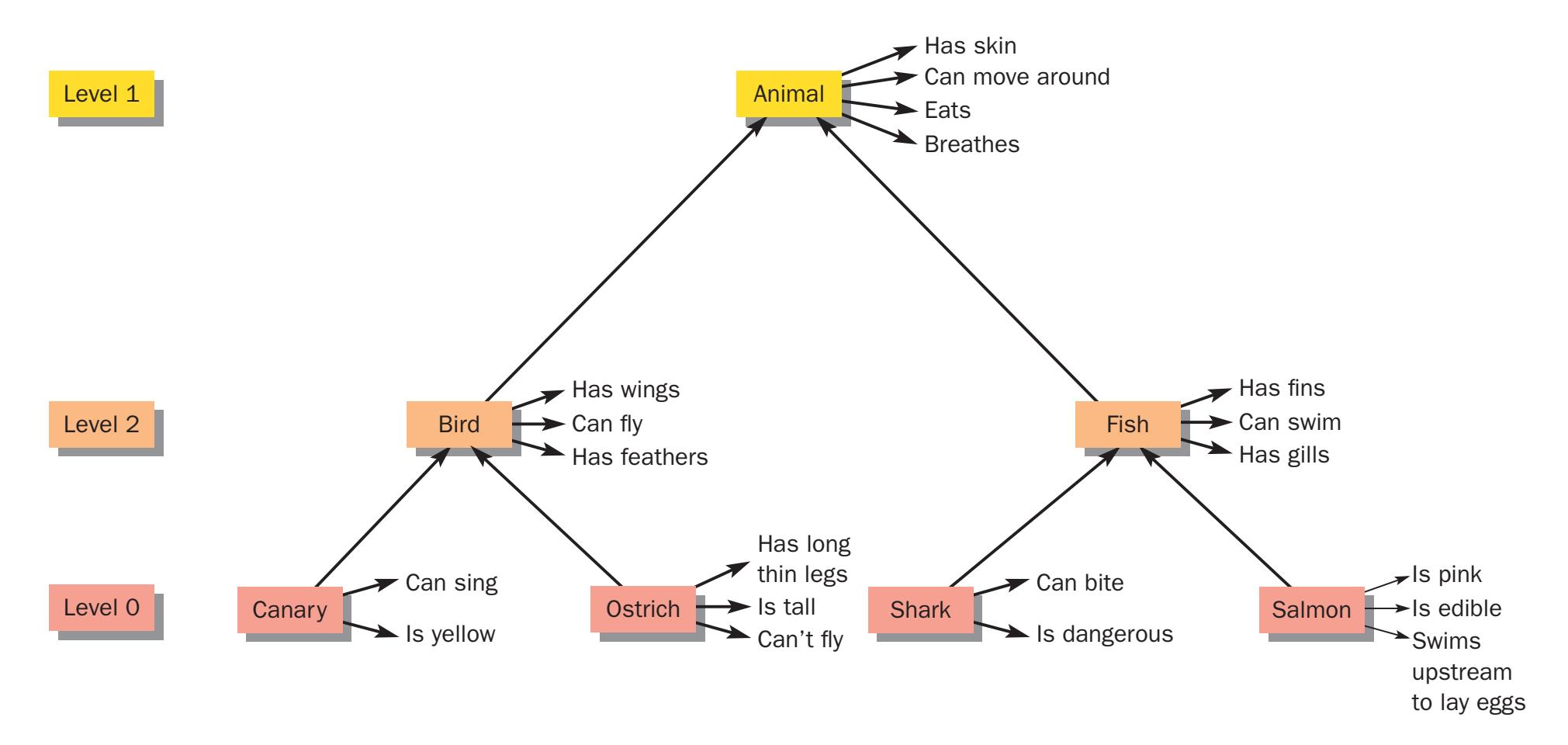

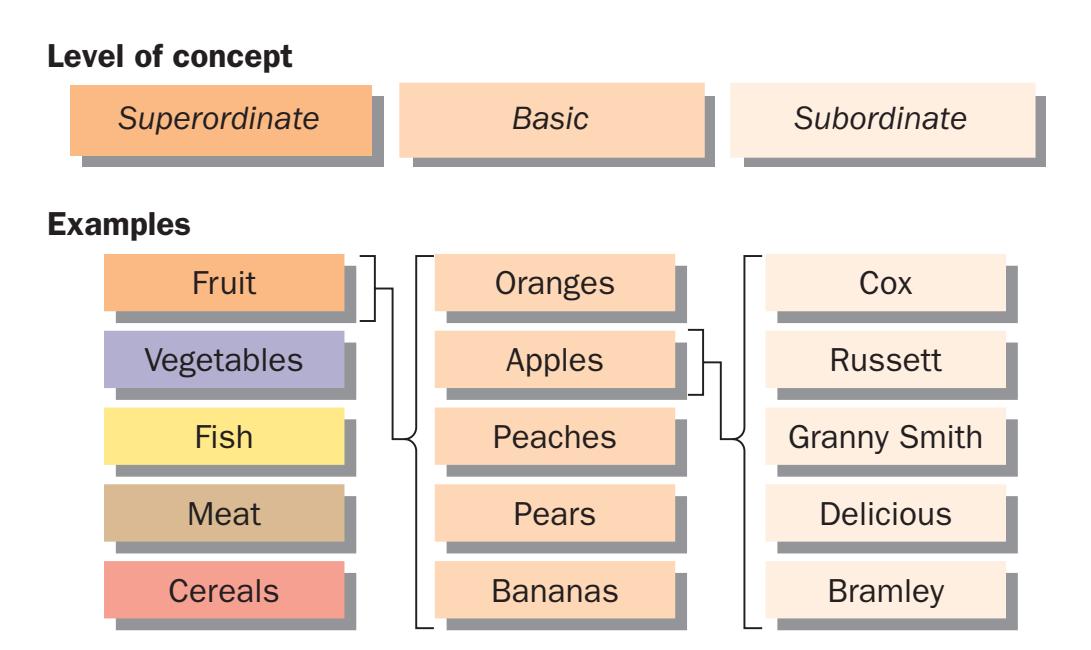

**Cognitive psychology** is the study of mental processes and complex behaviours such as perception, attention, learning, memory, concept formation and problemsolving. Explanations in cognitive psychology involve characteristics of inferred mental processes, such as imagery, attention, and mechanisms of language. Most cognitive psychologists do not study physiological mechanisms, but recently some have begun applying neuroimaging methods to studying cognitive function. A branch of cognitive psychology called **cognitive science** involves the modelling of human function using computer simulation or 'neural networks'. We briefly examine the contribution of such computer simulations to our understanding of behaviour in Chapters 7 and 10.

**Developmental psychology** is the study of physical, cognitive, emotional and social development, especially of children (Berk, 2009) but, more broadly, of humans from foetus to old age (these psychologists are sometimes called lifespan developmental psychologists). Some developmental psychologists study the effects of old age on behaviour and the body (a field called gerontology). Most developmental psychologists restrict their study to a

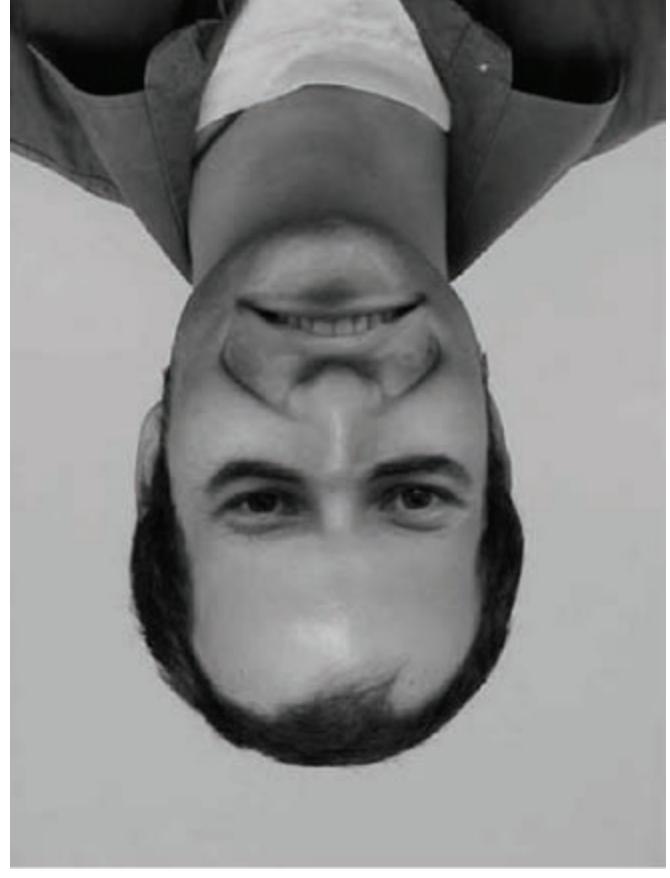

## **Cutting edge:** See no evil? Not quite . . .

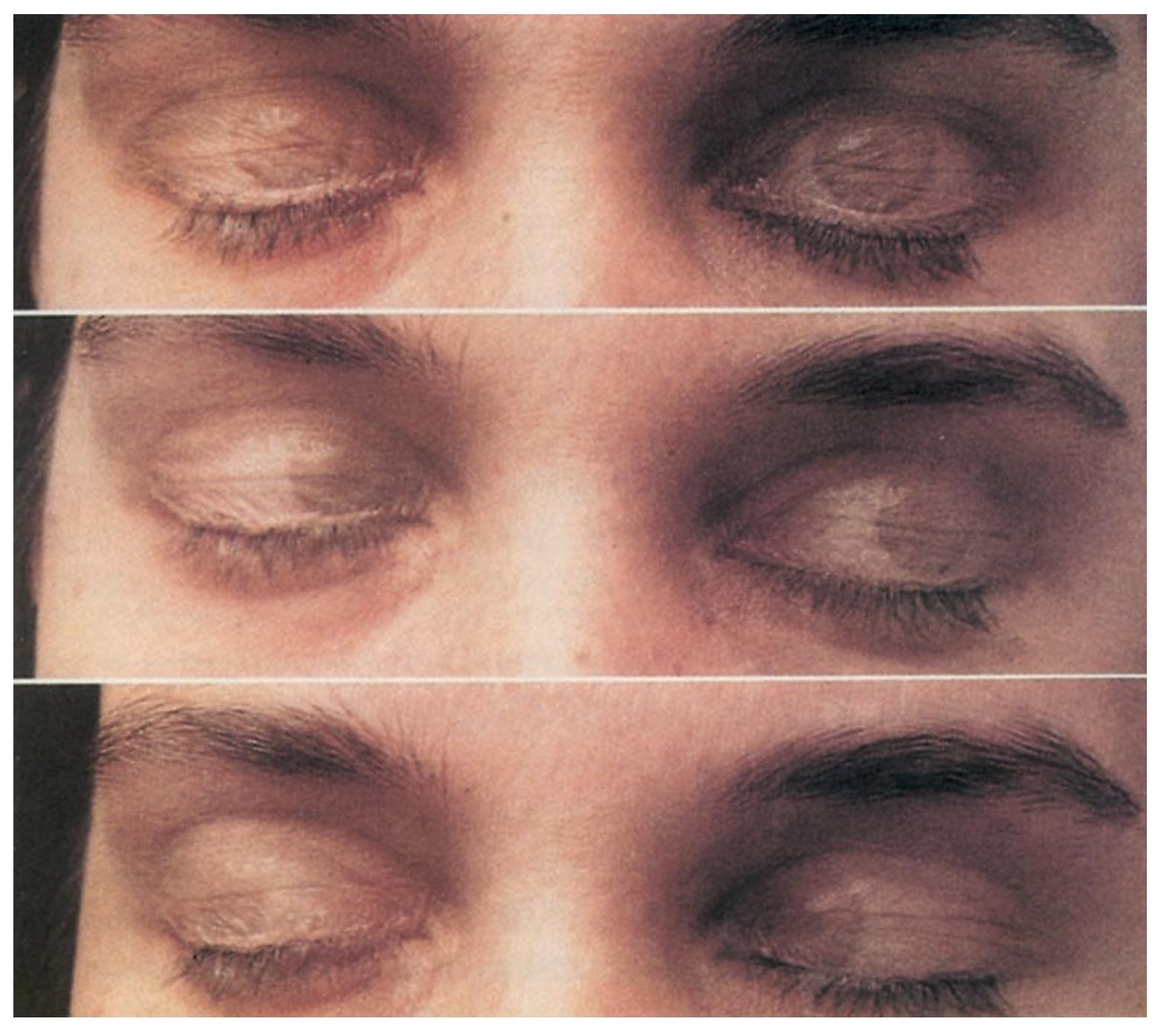

Turning a blind eye to something that is wrong, you would probably universally conclude, is morally indefensible. The fabled trio of monkeys (see no evil, hear no evil, . . . etc.) illustrates the dumb ignorance of a position where evil is allowed to prosper because it is ignored. But what if you could literally see no evil? How would your judgements of morality be made if, for example, you judged moral dilemmas with your eyes closed?

It sounds an odd question, but cast your mind back to the film *A Time to Kill*. Defence lawyer, Jake Brigance, asks the jury to close their eyes while he is summing up. The technique is adopted because lawyers think this helps people visualise events better. A study from a group of researchers from Harvard and Chicago Universities has now found that closing your eyes also influences your moral decision-making (Caruso and Gino, 2011).

In a series of four experiments, students were asked to make decisions when presented with a series of moral dilemmas. In one study, for example, people listened to a scenario where the participant was to hire a person in his company. A good friend rings up and suggests a potential candidate who is less qualified than the one the participant

has already considered. The friend offers the participant more business if the less-qualified candidate is employed. Should the participant accept the less-qualified person? Participants made the decision with eyes closed and open.

The researchers found that when eyes were closed, moral decisions were more black and white than when open: it discouraged dishonest behaviour strongly. Unethical behaviour was considered more unethical and ethical behaviour was considered more ethical when eyes were closed.

The effect was unrelated to attention (one argument suggested that people could visualise better with eyes closed and, therefore, pay more attention to detail). However, when attention was controlled for in another experiment, the same effect was found, suggesting that this factor does not influence the results. The authors suggest that there is something unique about having the eyes closed – they cite research showing how brain activation changes depending on whether a person listens to music with eyes open or the same music with eyes closed.

The message seems to be: don't turn a blind eye, close your eyes; then, think.

12 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

particular period of development, such as infancy, adolescence or old age. This field is described and illustrated in more detail in Chapter 12. The development of children's language is described in Chapter 10, and the effects of old age on cognition in Chapter 11.

**Social psychology** is the study of the effects of people on people. Social psychologists explore phenomena such as self-perception and the perception of others, causeand-effect relations in human interactions, attitudes and opinions, interpersonal relationships, group dynamics and emotional behaviours, including aggression and sexual attraction (Hogg and Vaughan, 2007). Chapters 15 and 16 explore these issues and themes in social psychology. An example of how we interpret the social behaviour of others is considered in the Psychology in action section below.

## **Psychology in action:** How to detect a liar

Take a look at this list of behaviours. Which do you think are characteristic of a person who is lying and why?

- Averting gaze

- Unnatural posture

- Posture change

- Scratching/touching parts of the body

- Playing with hair or objects

- Placing the hand over the mouth

- Placing the hand over the eyes

According to a standard manual of police interviewing, all of these features are characteristic of a liar (Inbau *et al*., 1986). A study of participants in 75 countries found that 'averting gaze' was described as the best tell-tale sign of lying (Global Deception Research Team, 2006).

Unfortunately, despite the manual's exhortations and the international guesswork, none of these behaviours is actually reliably associated with deception and several studies have shown that general law enforcement officers are usually as poor as the average undergraduate at detecting truth and falsity. We can tell the difference between truth and falsity with 50% accuracy (Bond & DePaulo, 2006). Research by psychologists such as Aldert Vrij, for example, has highlighted how bad people are at detecting whether someone is telling the truth or is lying (Vrij, 2000, 2004b). They usually construct a false stereotype of a lying person which has little association with actual liars.

Studies of police officers and students report detection rates of between 40 and 60 per cent – a result no better than expected by chance (Vrij and Mann, 2001; Vrij, 2000). Police

▼

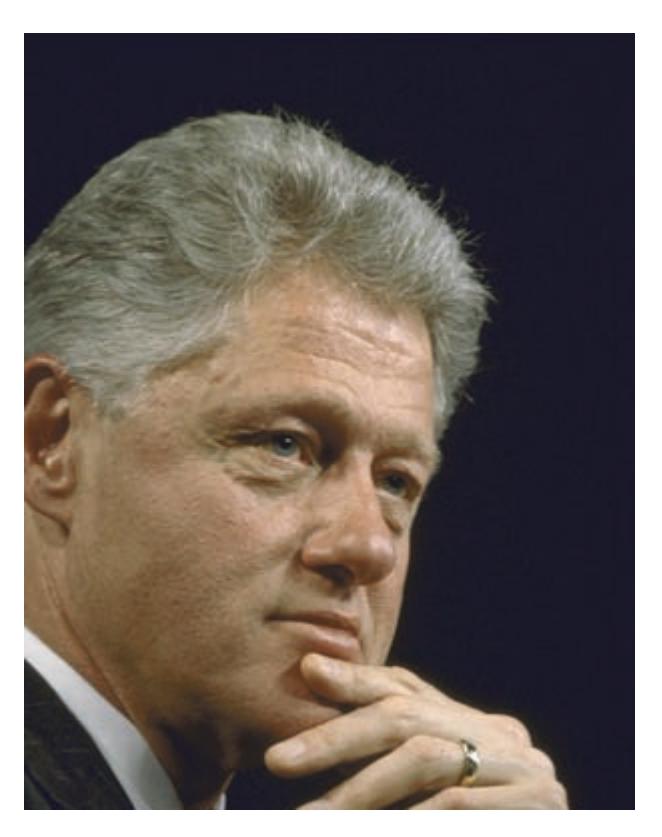

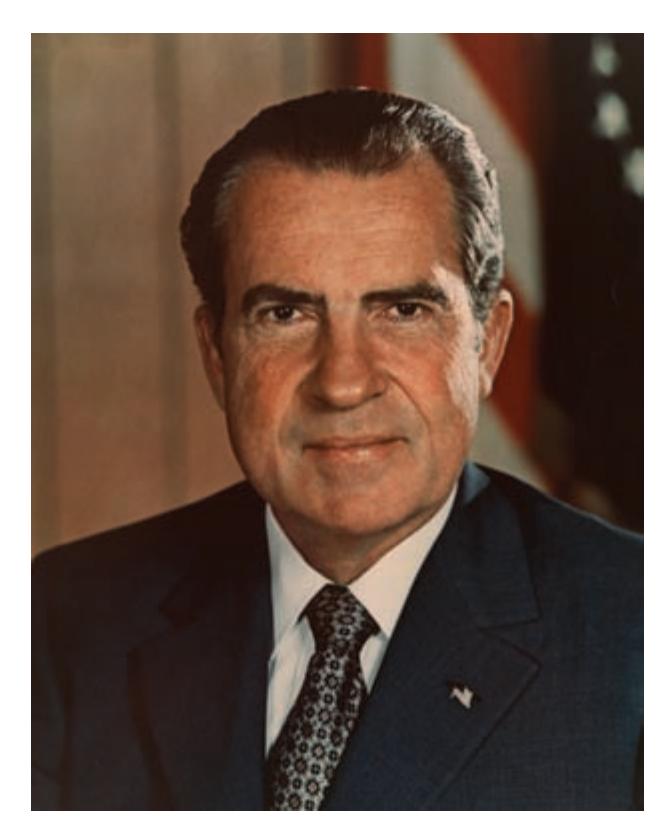

Former American President Bill Clinton, British novelist Jeffrey Archer and former American President Richard Nixon. What features might have revealed that they were lying? Clinton claimed not to have had sexual relations with his intern, Monica Lewinsky, Jeffrey Archer was convicted of perjury and Richard Nixon authorised but denied the tapping of 17 government officials' and reporters' telephones and those of opponents at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate apartments.

*Source*: Getty Images: Diana Walker/Time & Life Images (l); Matt Turner (c); Archive Photos (r).

What is psychology? 13

## **Psychology in action:** *Continued*

officers and people who use the polygraph technique – the so-called lie detector – generally do no better than students (Ekman and O'Sullivan, 1991). The exception to this generally ignominious performance seems to be Secret Service agents (Ekman *et al*., 1999). These groups tend to perform better than students and general law enforcement officers.

Perhaps the best detectors of dissembling would be those who routinely lie in order to get out of trouble. Researchers from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden (Hartwig *et al*., 2004) found that criminals were significantly better than students at detecting liars. However, this finding was coloured by another – the criminals also detected fewer truth-tellers. The lie bias – that criminals are more likely to judge that someone is lying than telling the truth – might stem from the fact that criminals are naturally suspicious (because they are used to being lied to, whether in prison or in the context of their relationships with others) and because they themselves are practised liars (and, therefore, expect the worst of others).

In another study, adult male offenders from a medium security Canadian prison and a group of undergraduates were asked to recall four emotional events from their lives (Porter *et al*., 2008) but lie about two of them. The researchers measured the number of illustrators (the use of hands to signify something), self-manipulations (touching/scratching the hand, head or body), frequency of head movement and number of smiles and laughs. Verbal indicators included the number of words spoken per minute, filled pauses ('umms' and 'ahs'), self-references and pauses that were longer than two seconds. Illustrators were higher when lying than when telling the truth in both groups. Offenders, however, used more self-manipulations when lying compared with non-offenders, a finding that seems to contradict previous studies. The authors suggest that this may be due to the specific context in which experiments take place, the type of lie, motivation, the consequences of the lie, and so on. The offenders also smiled less than the students when lying about emotional events.

Of course, these deception studies are fairly artificial. Interviewing suspects, the police would argue, gives you much more information on which to base a judgement. So, does it? Studies have shown that people who observe such interviews are better at discriminating between truth-tellers and liars than are the interviewers themselves (Buller *et al*., 1991; Granhag and Stromwall, 2001). Interviewers also showed evidence of truth bias – the tendency to declare that someone was saying the truth when they were not.

People tend to focus on different behavioural cues when deciding on whether a person is telling the truth or lying, with people relying on verbal cues when judging the truthfulness of a story and on non-verbal cues when the story is deceptive (Anderson *et al*., 1999). A recent review suggests that the behaviours people claim to use when they detect lying are inaccurate, but the behaviours they actually use as cues show some overlap with objective clues (Hartwig and Bond, 2011).

So, what are the most reliable indices of lying? Is there a 'Pinocchio's nose'? Two of the most fairly reliable indicators appear to be a high-pitched voice and a decrease in hand movements. But the way in which people are asked to identify lying is also important. For example, people are less accurate detectors when asked, 'Is this person lying?' than when asked 'Does the person x sincerely like the person y?' (Vrij, 2001). When people are questioned indirectly they tend to focus on those behavioural cues that have been found to predict deception, such as decreased hand movement, rather than those that do not (Vrij, 2001).

New research on lying is presenting us with some counter intuitive and challenging findings about psychology and human behaviour. Often, as you saw in the Controversies in Psychological Science section earlier, these studies contradict 'received wisdom' and 'common sense'.

**Individual differences** is an area of psychology which examines individual differences in temperament and patterns of behaviour. Some examples of these include personality, intelligence, hand preference, sex and age. Chapters 11 and 14 describe some of these in detail.

**Cross-cultural psychology** is the study of the impact of culture on behaviour. The ancestors of people of different racial and ethnic groups lived in different environments which presented them with different problems and opportunities for solving those problems. Different cultures have, therefore, developed different strategies for adapting to their environments. These strategies show themselves in laws, customs, myths, religious beliefs and ethical principles as well as

in thinking, health beliefs and approaches to problem-solving. A slightly different name – **cultural psychology** – is given to the study of variations within cultures (not necessarily across cultures). Throughout the book, you will find a section entitled, '… An international perspective', which takes a topic in psychology and examines how it has been studied cross-culturally, e.g. Are personality traits, recognition of emotion, memory, mental illness, and so on culture-specific?

**Forensic** and **criminological psychology** applies psychological knowledge to the understanding, prediction and nature of crime and behaviour related to crime. There is a distinction between criminological and forensic psychology. Forensic psychologists can be 14 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

commissioned by courts to prepare reports on the fitness of a defendant to stand trial, on the general psychological state of the defendant, on aspects of psychological research (such as post-traumatic stress disorders), on the behaviour of children involved in custody disputes, and so on. Criminological psychology refers to the application of psychological principles to the criminal justice system. The terms, however, are often used interchangeably.

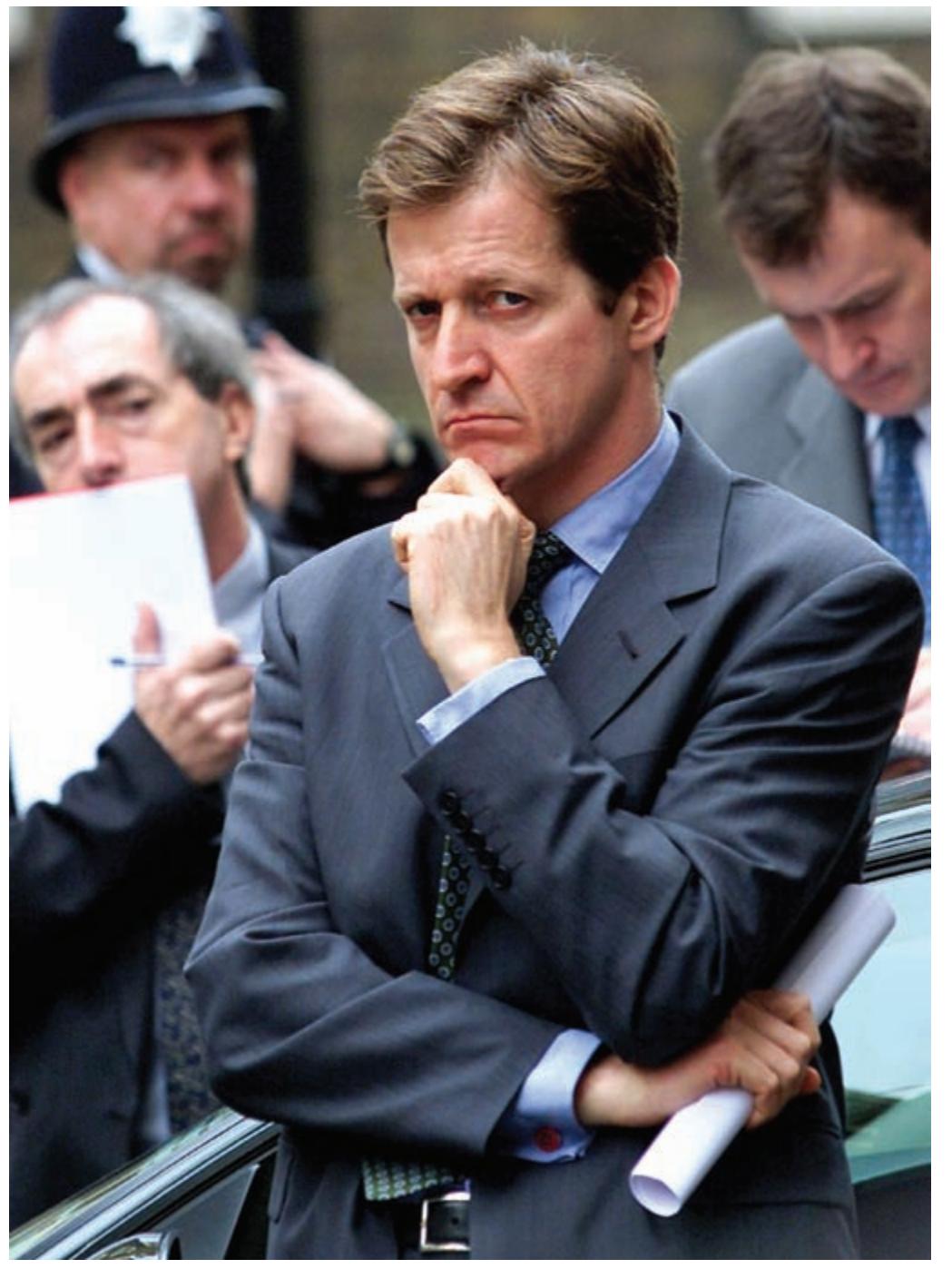

**Clinical psychology** is probably the field most closely identified with applied psychology and psychology in general and aims 'to reduce psychological distress and to enhance and promote psychological well-being' (BPS Division of Clinical Psychology, 2012). It is an applied branch of psychology because clinical psychologists do not work in the laboratory under well-controlled experimental conditions but out in the field (usually clinic or hospital), applying the knowledge gained from practice and research. Clinical psychologists address problems caused by mental illnesses (see Chapter 18), and mental illness is one of the most widely misunderstood illnesses and the most peculiarly reported. It is also one of the most stigmatised – people feel embarrassed about mental illness and others may respond to sufferers unsympathetically because they do not understand the disorder. Hence, public figures such as the former UK government Director of Communications, Alastair Campbell, the comedian, Ruby Wax, and the actor and writer, Stephen Fry, have made their illnesses known and have promoted their public understanding.

Whether such promotion and the emphasis on illness succeeds in making the stigma less strident, however, is unclear. When Read and Harre (2001) asked psychology students questions such as would you be happy being romantically involved with someone who has spent time in a psychiatric hospital, those who were more likely to believe in biological/genetic causes of mental disorder

were more likely to avoid mentally ill people and regard the mentally ill as unpredictable and dangerous. This finding was replicated in a study in which people saw a man hallucinating and expressing delusions – when his behaviour was given a biological or genetic explanation, people were more likely to regard him as dangerous and unpredictable (Walker and Read, 2002).

An analysis of the portrayal of mental illness in a week's worth of children's programmes on two television stations in New Zealand found that over 45 per cent contained reference to mental illness and most of these were: 'crazy', 'mad' and 'losing your mind', although 'mad' and 'crazy' were interchangeably used to mean 'angry' (Wilson *et al*., 2000). Other terms included 'driven bananas', 'wacko', 'nuts', 'loony', 'cuckoo' and 'freak'. Mental illness was frequently portrayed as reflecting a loss of control. Characters at the receiving end of these epithets were routinely and invariably seen as negative, as objects of amusement or derision or as objects of fear. The characters were either comical or villainous. Psychologists have identified views such as these and proposed ways of changing them (see Chapter 18).

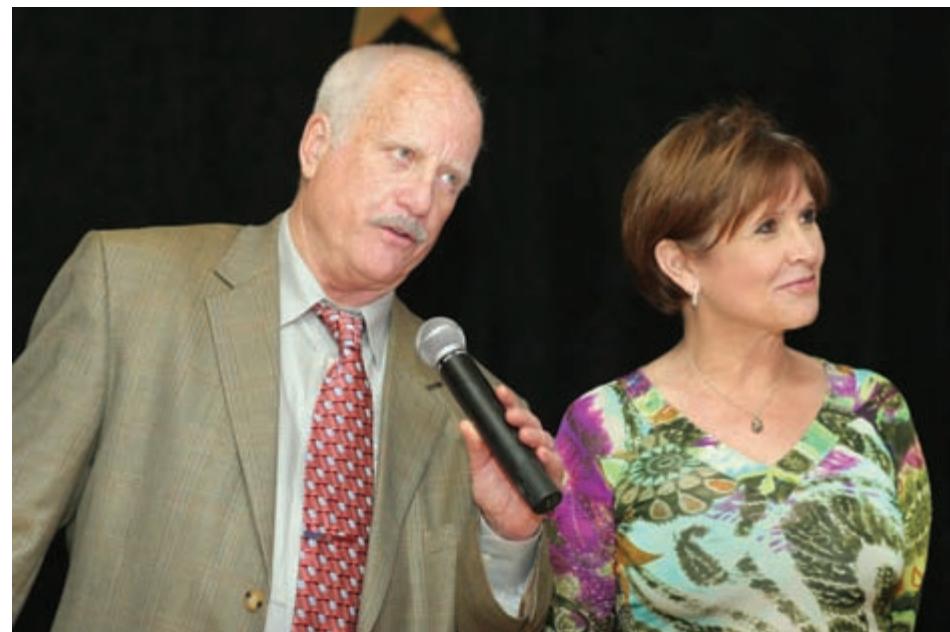

Alastair Campbell and Ruby Wax, two tireless campaigners for the public undertstanding of mental illness. *Source*: Corbis: Robbie Jack (l); Reuters (r)

Psychology: a European perspective 15

**Health psychology** is the study of the ways in which behaviour and lifestyle can affect health and illness (Sarafino, 2011). For example, smoking is associated with a number of illnesses and is a risk factor for serious illness and death. Health psychologists study what makes people initiate and maintain such unhealthy behaviour and can help devise strategies to reduce it. Health psychologists are employed in a variety of settings including hospitals, government, universities and private practice (see Chapter 17).

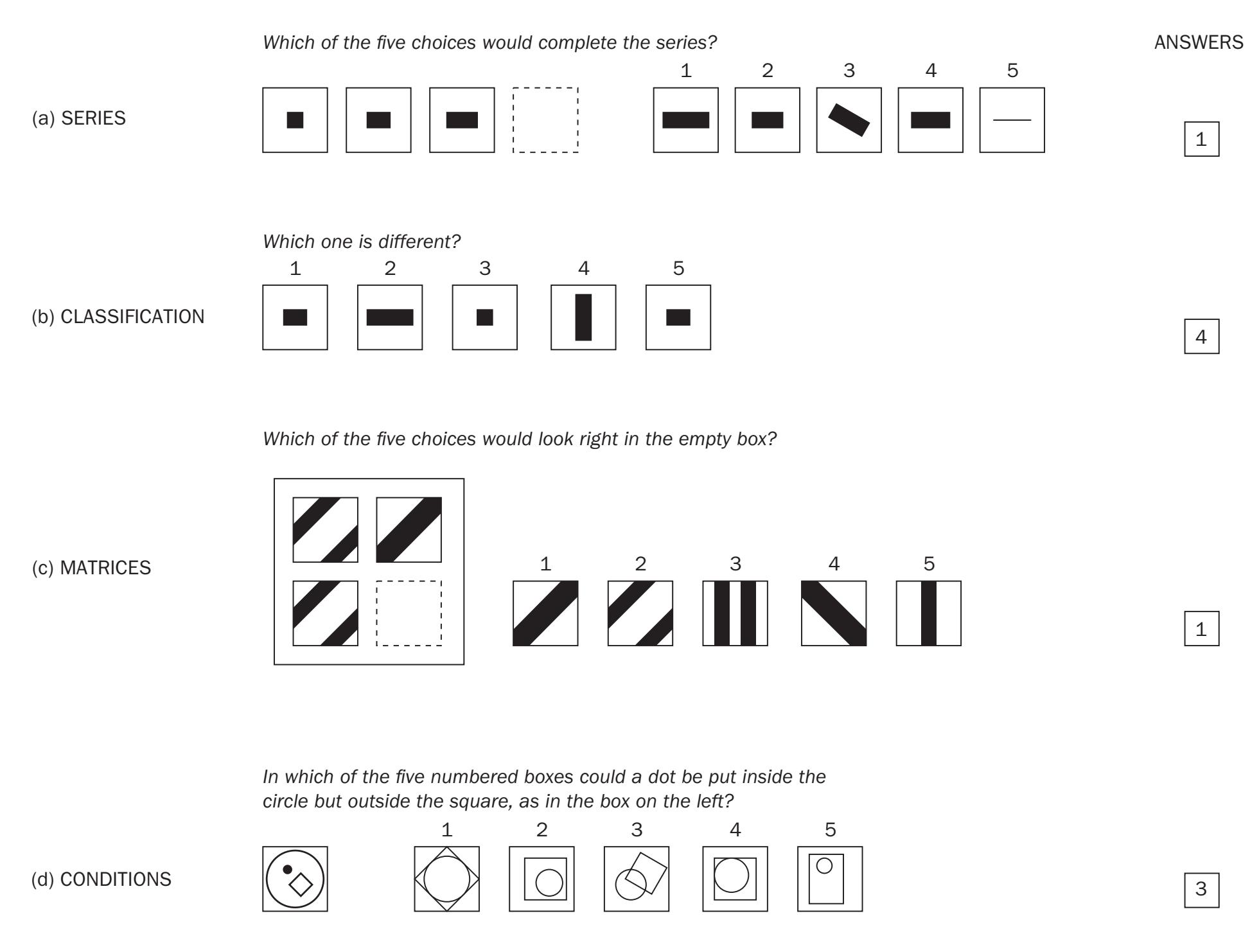

**Educational psychology** is another branch of applied psychology. Educational psychologists assess the behavioural problems of children at school and suggest ways in which these problems may be remedied. For example, the educational psychologist might identify a child's early inability to read (dyslexia) and suggest a means by which this may be overcome through special training. The educational psychologist might also deal with all aspects relevant to a child's schooling such as learning, social relations, assessment, disruptive behaviour, substance abuse, bullying and parental neglect.

**Consumer psychology** is the study of the motivation, perception, learning, cognition and purchasing behaviour of individuals in the marketplace and their use of products once they reach the home. Some consumer psychologists take a marketer's perspective, some take a consumer's perspective, and some adopt a neutral perspective, especially if they work at a university.

**Organisational** or **occupational psychology** is one of the largest and oldest fields of applied psychology and involves the study of the ways in which individuals and groups perform and behave in the workplace (Huczynski and Buchanan, 2010). Early organisational psychologists concentrated on industrial work processes (such as the most efficient way to shovel coal), but organisational psychologists now spend more effort analysing modern plants and offices. Most are employed by large companies and organisations.

A related branch, **ergonomics** or **human factors psychology**, focuses mainly on the ways in which people and machines work together. They study machines ranging from cockpits to computers, from robots to MP3/4 players, from transportation vehicles for the disabled to telephones. If the machine is well designed, the task can be much easier, more enjoyable and safer. Ergonomists help designers and engineers to design better machines; because of this, the terms ergonomics and engineering psychology are sometimes used interchangeably.

**Sport and exercise psychology** applies psychological principles to the area of sport. It also involves the study of the effects of sport and exercise on mood, cognition, well-being and physiology. This area is examined in more detail in Chapter 17.

## **Psychology: a European perspective**

Psychology is one of the most popular degree courses in Europe. In 2009–10, psychology was the sixth most popular UK university degree in terms of applications (see Table 1.3). It is estimated that one in 850 people in the Netherlands has a degree in psychology (Van Drunen, 1995), and no course is more popular in Sweden (Persson, 1995).

Modern psychology has its origins in Europe: the first psychological laboratory was established in Europe and some of the first designated university degrees in psychology were established there. Research in North America

## **Psychology –** An international perspective

Behind almost all research endeavours in psychology is a common aim: to discover a psychological universal. According to Norenzayan and Heine (2005), **psychological universals** are 'core mental attributes shared by humans everywhere'. That is, they are conclusions from psychological research that can be generalised across groups – ways of reasoning, thinking, making decisions, interpreting why people behave in the way that they do, recognising emotions and so on, are all examples of core mental attributes. A sound case for a psychological universal can be made if a phenomenon exists in a large variety of different cultures.

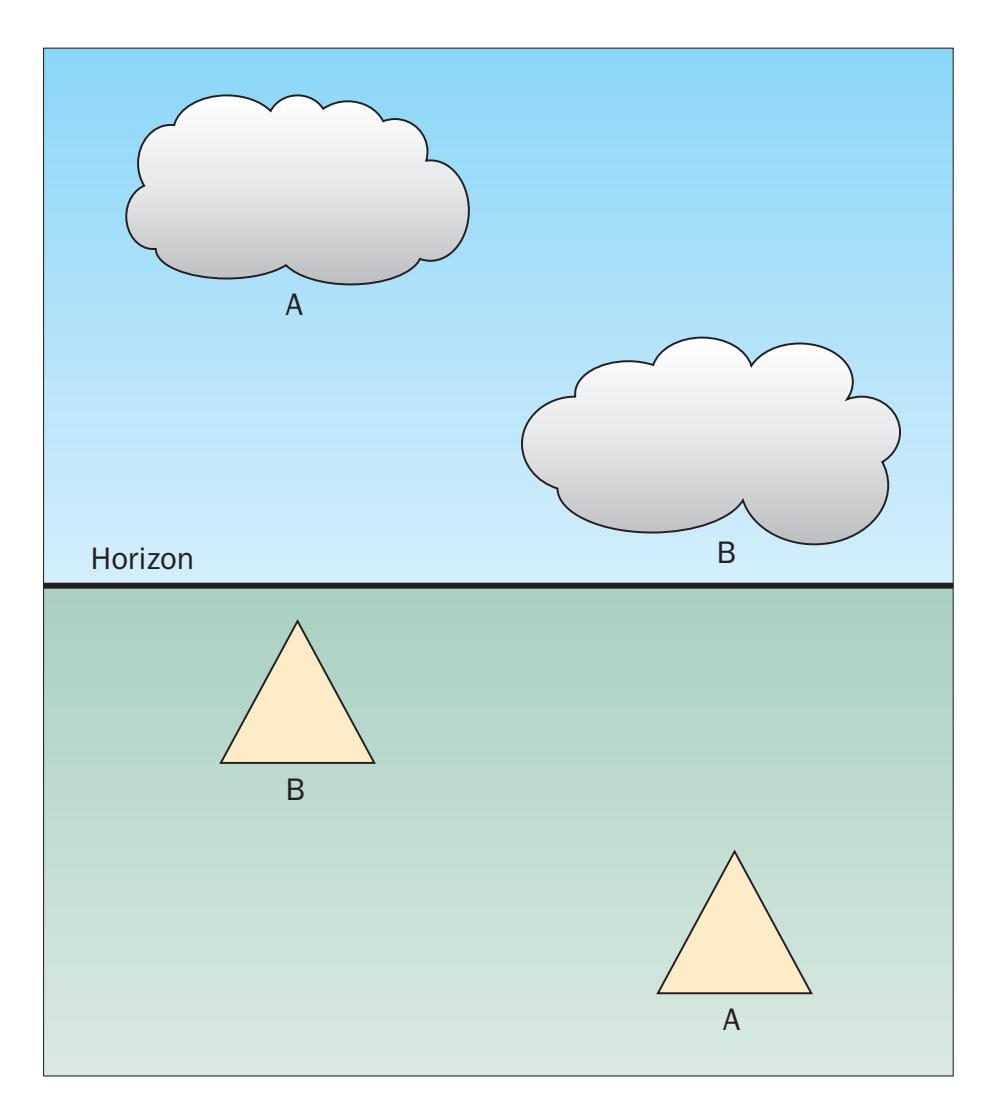

However, some differences may be more obvious in some groups than others – men and women, for example, the young and the old, the mentally ill and the mentally healthy, and so on. At this level of analysis, we cannot say that people in general behave in a particular way, but that a specific group of people behave in a particular way. Nowhere is this more relevant than when considering the role of culture in psychological studies. A variety of behaviours are absent or are limited in a variety of cultures and nations. Some recent research, for example, has highlighted significant differences between Western and Asian cultures in the types of autobiographical memory they recall, the parts of a landscape and photograph they focus on, and the way in which they draw and take a photograph (Varnum *et al*., 2010). Table 1.2 summarises some of these differences.

▲

16 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

## **Psychology –** *Continued*

Varnum *et al*. have noted that cultures can differ according to their social orientation so that some are independent and analytical and others are interdependent and holistic. Independent cultures emphasise the importance of self-direction, autonomy, the enhancement of self at the expense of others and they are self-expressive; interdependent cultures believe in being connected with others, working and living harmoniously and enhancement of the self at the expense of others is absent. The most common examples of such cultures are Western and East Asian, respectively, although these are very large categories and there will be considerable variation within them, let alone between them.

Northern Italians, for example, appear to be more independent than Southern Italians (Martella and Maass, 2000), are more analytic and categorise objects more taxonomically (Knight and Nisbett, 2007). Villages in the Black Sea region of Turkey also differ according to the type of economic activity they engage in. So, fishermen and farmers categorised objects more thematically and perceived scenes more contextually than did herders (Uskul *et al*., 2008). People who move and move often are more likely to show a personal than a collective sense of identity (Oishi, 2010).

Some countries appear to bridge the two types of approach. Russians, for example, appear to be more interdependent than are Germans (Naumov, 1996) and they reason and visually perceive stimuli more holistically (looking at the whole and the context, rather than a part of a scene, say). Croats show a similar pattern of behaviour to Russians (Varnum *et al*., 2008).

A way of demonstrating a psychological universal is to examine a behaviour in three or more cultures, two of which are very different, with a third falling between them, and see how each differs from, or is similar to, the other. The best way, however, is to examine a variety of cultures, as Daly and Wilson (1988) did. Their research examined sex differences in the international rates of homicide and found that men were more likely to kill men than women were to kill women across all cultures. Debate then ensues as to why this universal should be (and that debate is often heated, as most in psychology are).

In the book, examples of universals (and exceptions) are described in the sections: ' . . . An international perspective'. These will help you put the findings you read about into some form of cultural or international context. They should also help demonstrate that although studies sometimes report findings as being absolute and generalisable to populations in general, sometimes these findings are not.

**Table 1.2** Behaviours/concepts reported to vary across cultures, or which may be less evident in certain cultures. Unfamiliar terms are defined in the chapters referred to in brackets

- • Memory for and categorisation of colours (see Chapter 6)

- • Spatial reasoning (see Chapter 8)

- • Autobiographical memory (see Chapter 8)

- Perception of the environment

- • Appreciation of art

- • Some types of category-based inductive reasoning (see Chapter 11)

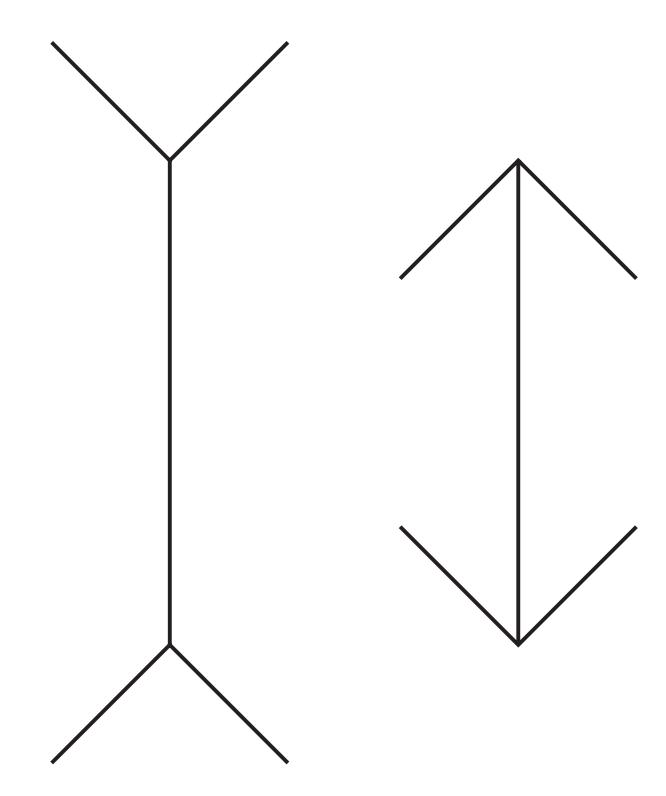

- • Some perceptual illusions

- • Some ways of approaching reasoning

- • Aspects of numerical reasoning

- • Risk preferences in decision-making (see Chapter 11)

- • Self-concept (see Chapters 15 and 16)

- • Similarity-attraction effect (see Chapters 15 and 16)

- • Approach-avoidance motivation (see Chapter 13)

- • The fundamental attribution error (see Chapters 15 and 16)

- Predilection for aggression

- • Feelings of control, dominance or subordination

- High subjective well-being and positive affect

- • Communication style

- Prevalence of major depression

- Prevalence of eating disorders (see Chapter 13)

- • Mental illness (see Chapter 18)

- Noun bias in language learning (see Chapter 10)

- Moral reasoning

- Prevalence of different attachment style (see Chapter 12)

- Disruptive behaviour in adolescence

- Personality types (see Chapter 14)

- • Response bias (see Chapter 2)

- Recognition of emotion

- Perception of happiness

- • Body shape preference

*Source*: Adapted from Norenzayan and Heine, 2005.

Psychology: a European perspective 17

**Table 1.3** The top degree subjects in the UK, as indexed by number of applications to study 2009/10

| Business studies | 43,785 |

|--------------------|--------|

| Nursing | 34,370 |

| Design studies | 24,805 |

| Management studies | 24,790 |

| Computing science | 24,485 |

| Psychology | 23,130 |

| Law | 17,480 |

and Europe accounts for the majority of psychological studies published in the world (Eysenck, 2001) and there continues to be debate over whether these two fairly large 'geographical' areas adopt genuinely different approaches to the study of psychological processes (G. N. Martin, 2001).

Psychology as a discipline occupies a different status in different European countries and each country has established its own degrees and societies at different times, for historical or political reasons. Almost all countries have a professional organisation which regulates the activity of psychologists or provides psychological training or licensing of psychologists. The first such association in Denmark was founded in 1929 (the Psychotechnical Institute in Copenhagen) and what we would now call educational psychology formed the basis of the professional training it provided: the job of the institute was to select apprentices for the printing trade (Foltveld, 1995). The Netherlands' first psychological laboratory was founded in 1892 at Gröningen, Denmark's in 1944 at the University of Copenhagen and Finland's in 1921 by Eino Kaila at the University of Turku (Saari, 1995). Coincidentally, 1921 was also the year in which the Netherlands passed a Higher Education Act allowing philosophy students to specialise in psychology.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) was formed in 1901, with laboratories established at the University of Cambridge and University College London in 1897, closely followed by the establishment of laboratories in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow (Lunt, 1995). Sweden's professional association was founded in 1955 (Sveriges Psykologforbund), with the Netherlands' pre-dating that in 1938 (Nederlandsch Instituut van Practizeerende Psychologen, or NIPP). Portugal is one of the younger psychology nations – the first students of psychology graduated in 1982 (Pereira, 1995). Because of the history of the country, psychology was not acknowledged as a university subject in Portugal until after the democratic revolution of 1974.

#### **Psychological training and status of psychology in Europe**

The types of career that psychology graduates pursue are similar across most European countries. Most psychologists are employed in the public sector, with the majority of those working in the clinical, educational or organisational fields. Training for psychologists varies between countries and controversy surrounds the licensing or the legalisation of the profession. For example, psychologists in almost all countries wish for formal statutory regulation of the profession (the medical and legal professions are regulated). In Denmark, the title of psychologist was legally protected in 1993 so that no one could call themselves a psychologist unless they had received specified training. In Greece, a law was passed in 1979 licensing psychologists to practise (Georgas, 1995). These enlightened views have not extended to some other countries, however, despite the attempts of professional organisations in lobbying their legislators. Finland and the UK have faced obstacles in legalising the profession.

The BPS has its own regulatory system so that applied psychologists need to undergo an approved route of training (to go on to practise as forensic, clinical, educational, health psychologists, for example) before they are recognised as qualified professional psychologists by the Society. Most of these individuals choose to register themselves as Chartered Psychologists – a person using the services of a psychologist designated chartered can, therefore, be assured that the person is a recognised professional psychologist.

#### **European views of psychology and psychologists**

Non-psychologists' views of what psychology is and what psychologists do are encouragingly positive and generally accurate although their knowledge of psychological research (as you saw earlier) is flawed. Table 1.4 shows you the responses of an Austrian sample to the question, 'What do you expect a psychologist to do?', and to the sentence, 'Psychologists can . . .' (Friedlmayer and Rossler, 1995).

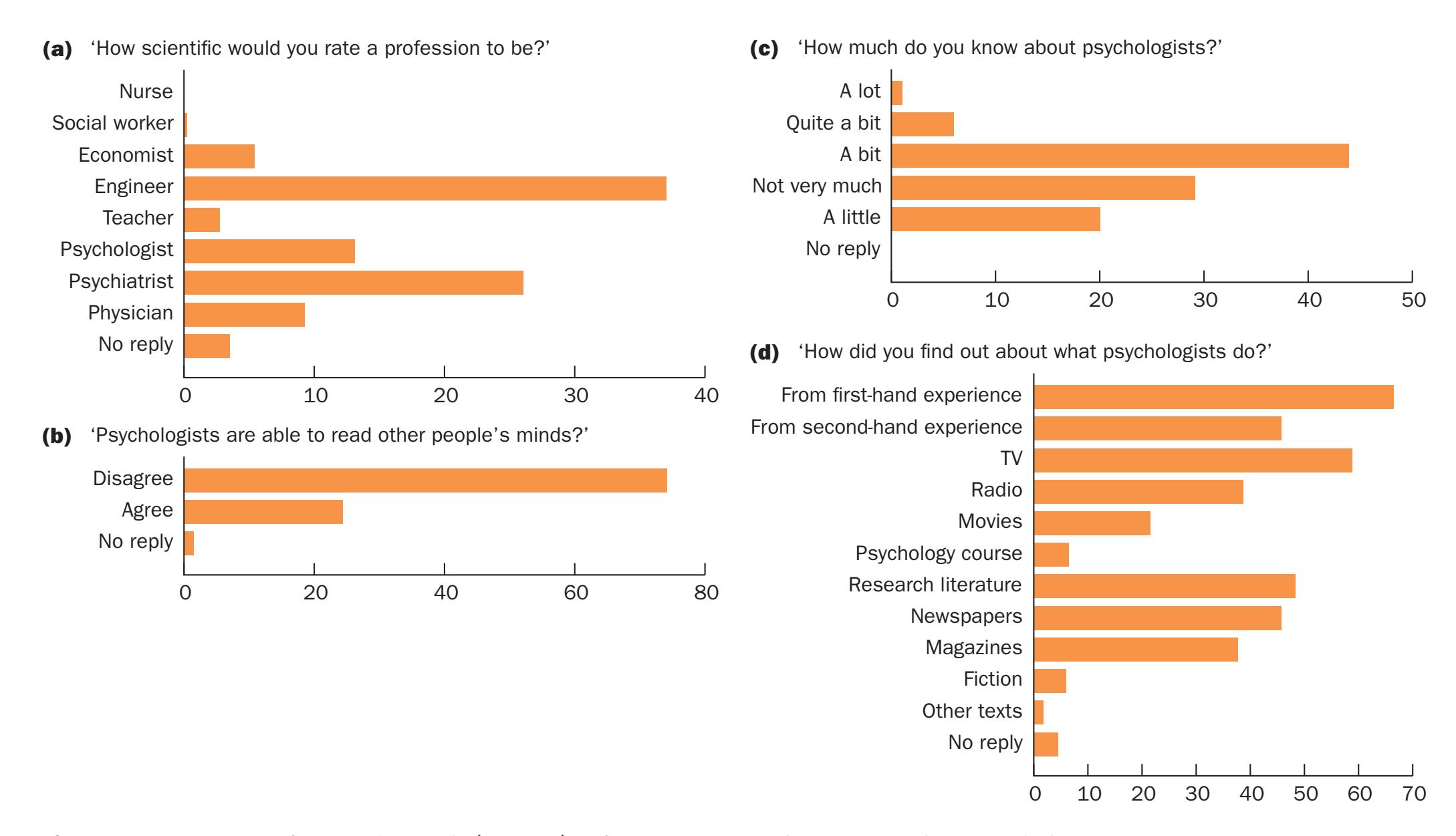

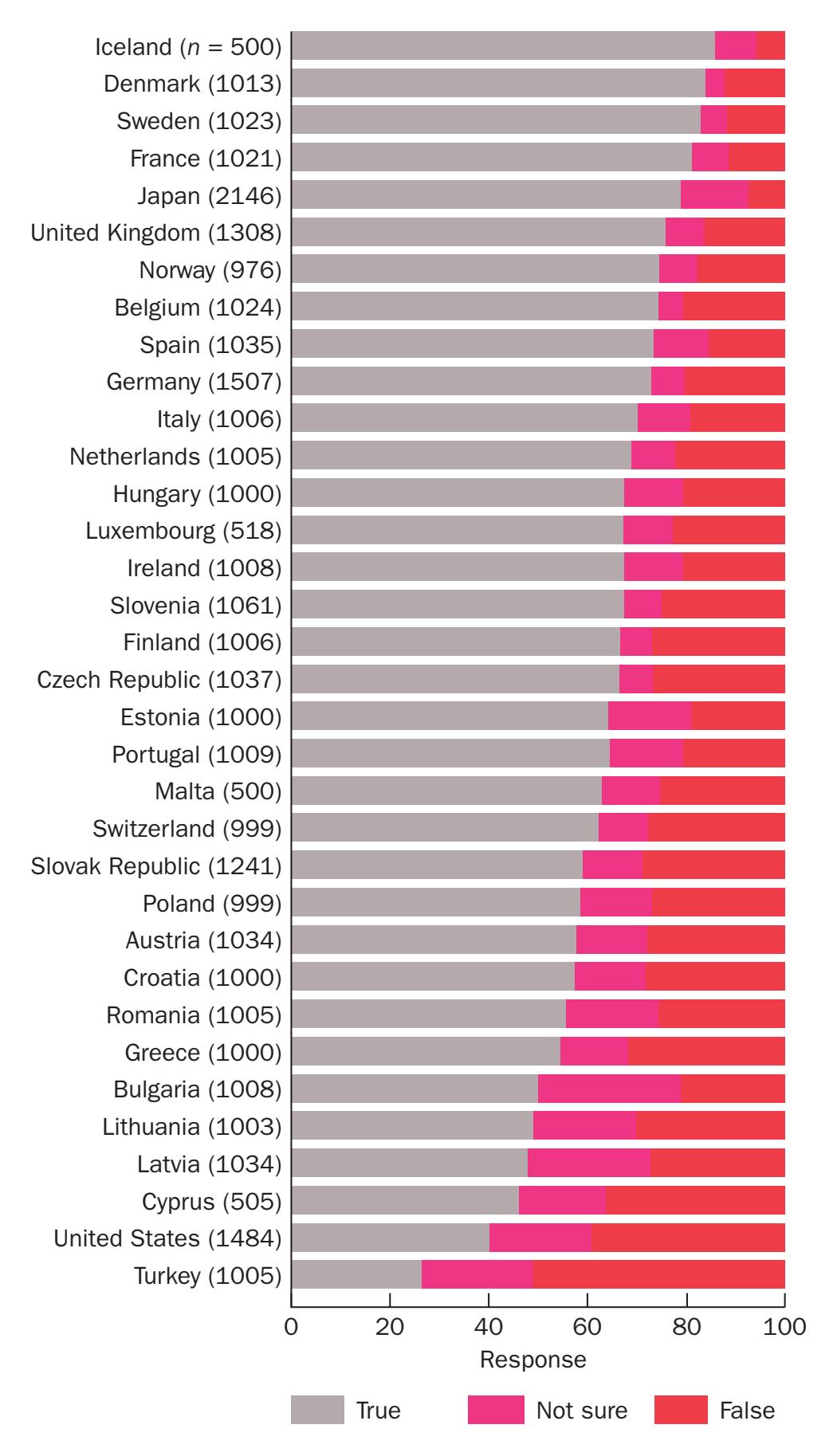

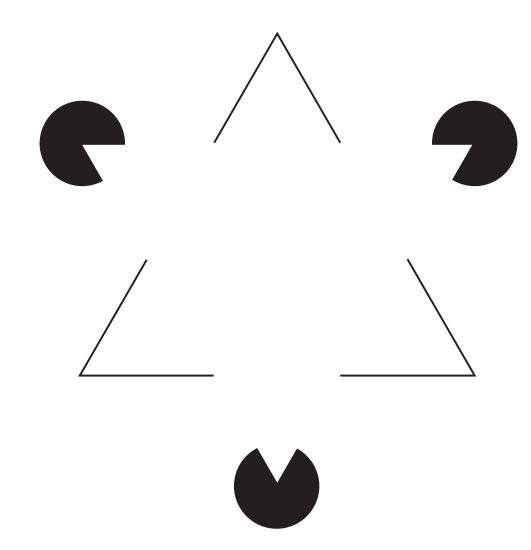

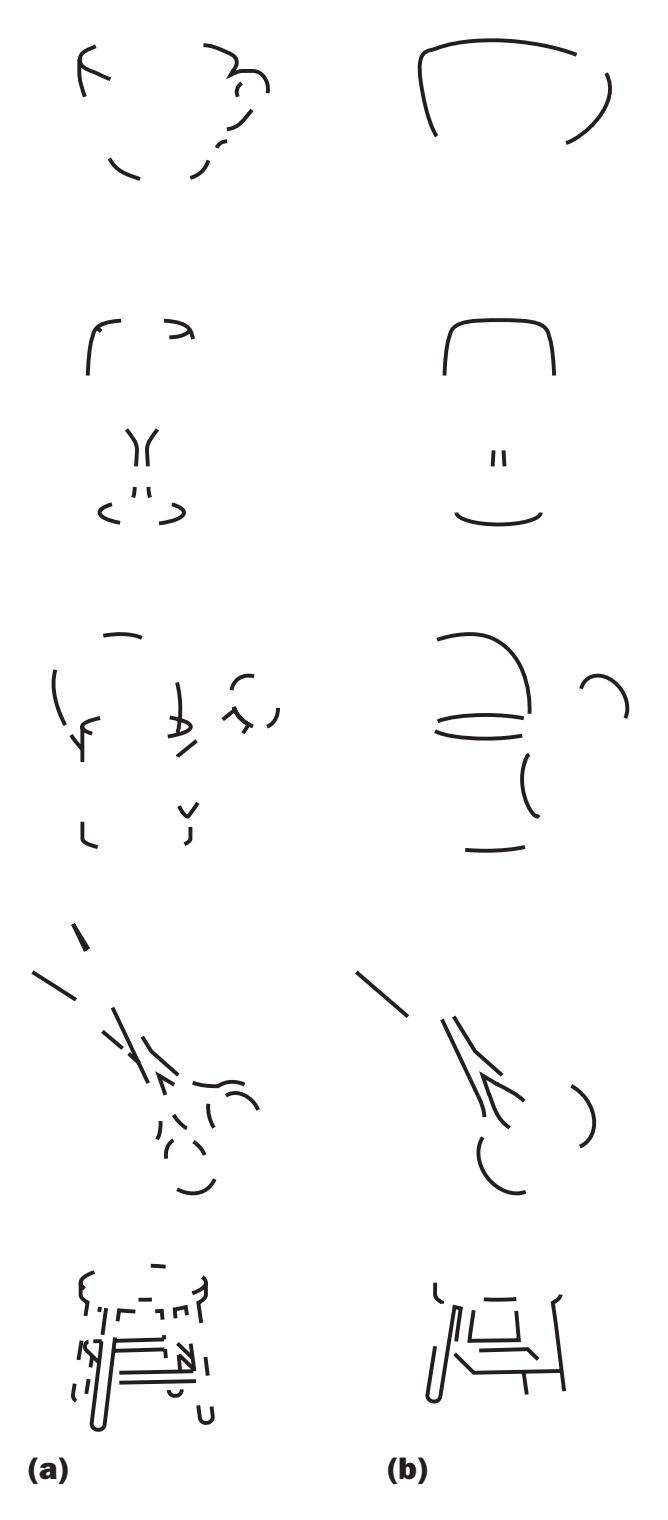

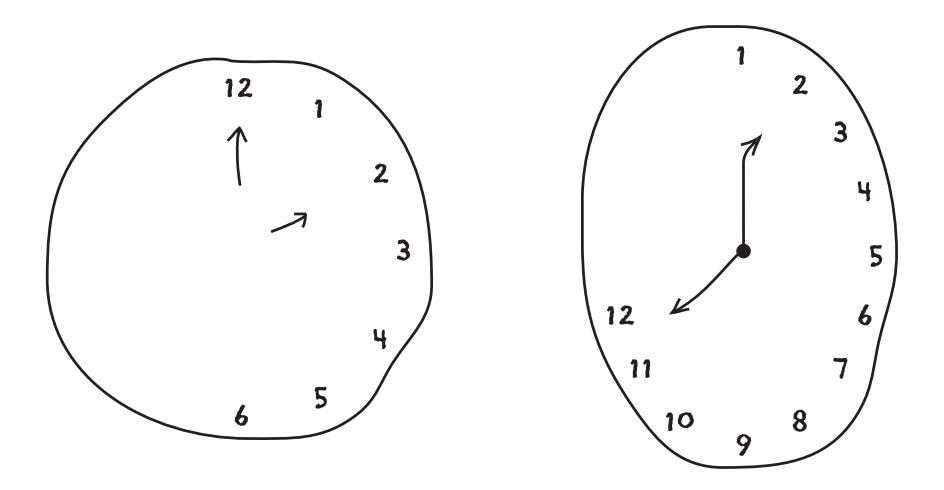

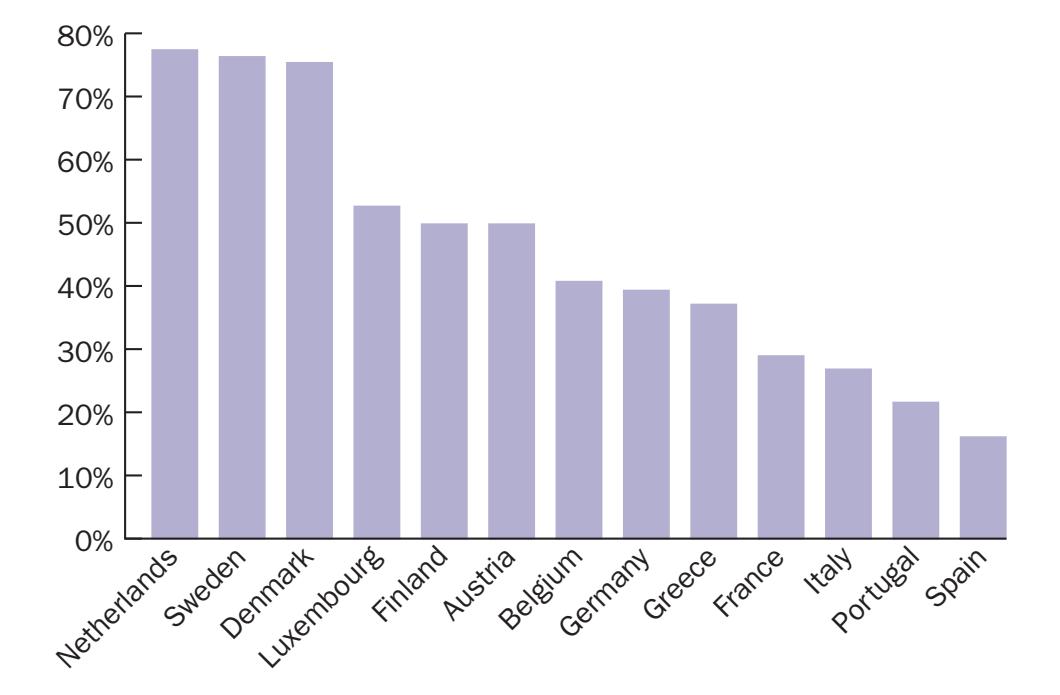

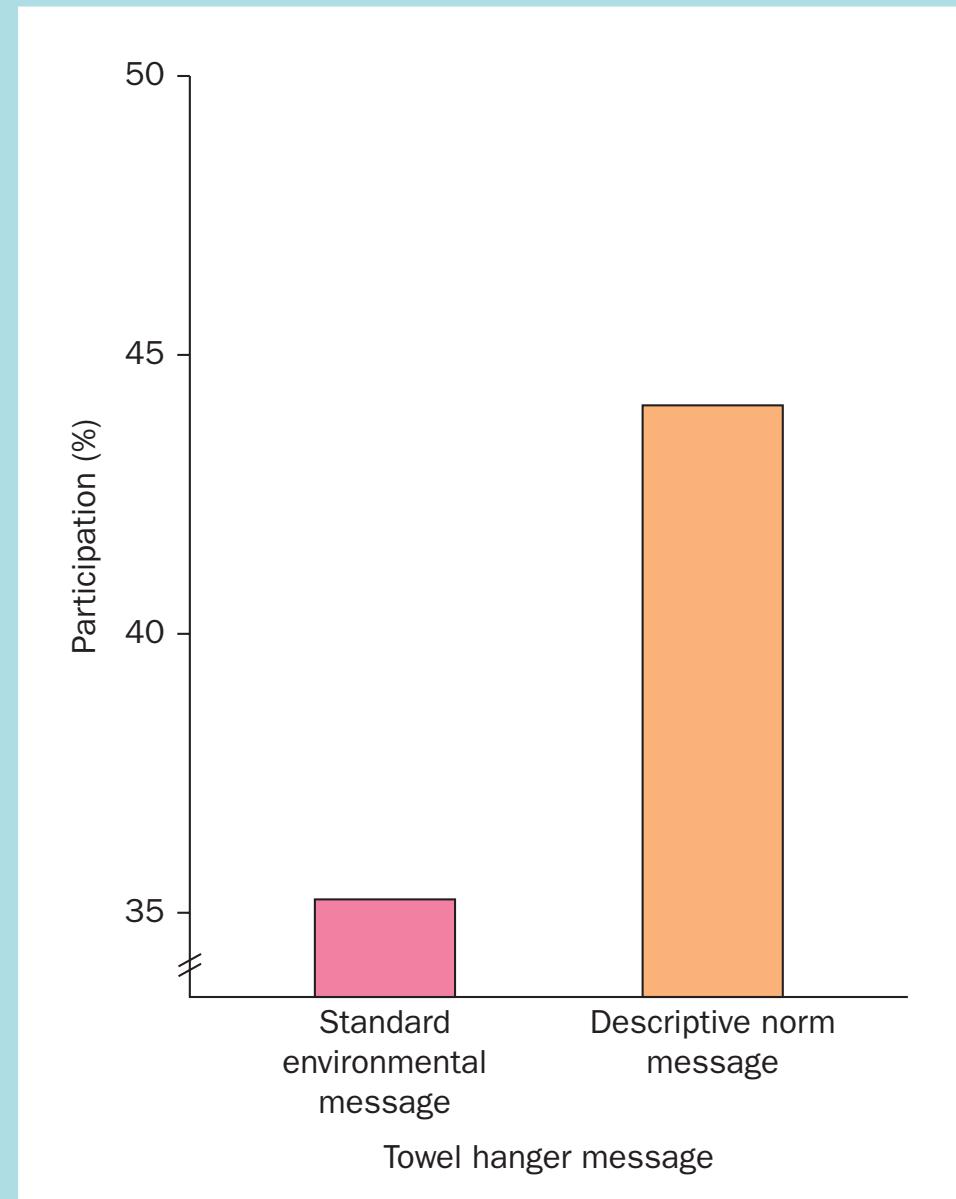

A Finnish study which asked adults to rate which of a number of professions was more knowledgeable about human nature found that 53 per cent believed doctors were more knowledgeable, with psychologists following behind in second place (29 per cent) (Montin, 1995). A Norwegian study, however, found the opposite: 49 per cent chose psychologists and 23 per cent chose doctors (Christiansen, 1986). Figures 1.2 (a)–(d) give some of the other illuminating responses to the other questions asked in the Finnish survey. These not only reveal how

18 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

**Table 1.4** Austrian views of psychologists (based on a sample of 300 respondents)

| Statement/question | % |

|----------------------------------------------|----|

| 'Psychologists can . . .' | |

| See through other people | 68 |

| Help other people to change | 72 |

| Help others to help themselves | 90 |

| Exert influence through reports | 57 |

| Release people from mental suffering | 62 |

| Listen patiently | 88 |

| Direct the attention of social policy-makers | 53 |

| Handle children well | 55 |

| Cause harm by making mistaken diagnoses | 68 |

| Make people happier | 54 |

| Statement/question | % |

| 'What do you expect a psychologist to do?' | |

| Talk | 97 |

| Test | 90 |

| File a report | 85 |

| Treatment/therapy | 91 |

| Train children | 46 |

| Proposing interventions | 86 |

| Negotiate conflicts | 65 |

| Give guidance and advice | 94 |

| Solve problems | 44 |

*Source*: Based on Friedlmayer, S. and Rossler, E., Professional identity and public image of Austrian psychologists. Reproduced with permission from *Psychology in Europe* by A. Schorr and S. Saari (eds), ISBN 0-88937-155-5, © Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Seattle, Toronto, Göttingen, Bern.

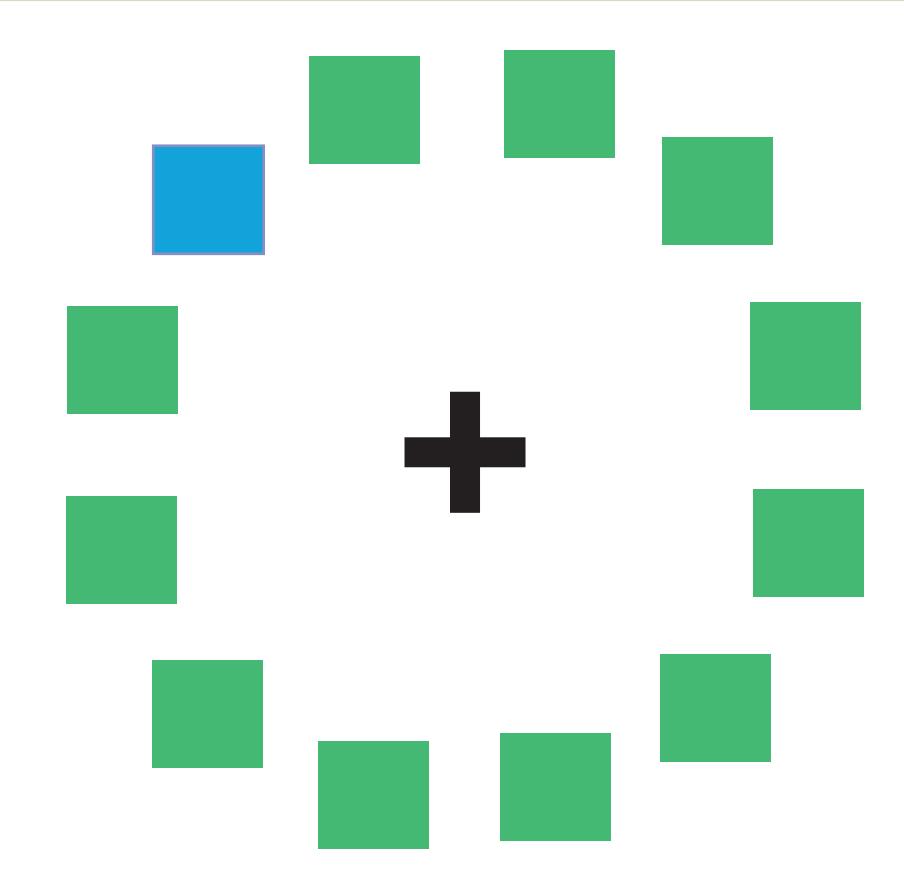

people receive or obtain their information about psychology but also show that the discipline is still shrouded in some mystery – 49 per cent declare knowing only 'a little' about psychology. Mercifully, 75 per cent of respondents disagreed that psychologists could read minds.

## **Psychology: the development of a science**

Although philosophers and other thinkers have been concerned with psychological issues for centuries, the science of psychology is comparatively young. To understand how this science came into being, it is useful to trace its roots back through philosophy and the natural sciences. These disciplines originally provided the methods we use to study human behaviour and took many centuries to develop.

#### **Philosophical roots of psychology**

#### *Animism*

Each of us is conscious of our own existence. Furthermore, we are aware of this consciousness. Although we often find ourselves doing things that we had not planned to do (or had planned not to do), by and large we feel that we are in control of our behaviour. That is, we have the impression that our conscious mind controls our behaviour. We consider alternatives, make plans, and then act. We get our bodies moving; we engage in behaviour.

Earlier in human history, philosophers attributed a lifegiving animus, or spirit, to anything that seemed to move or grow independently. Because they believed that the movements of their own bodies were controlled by their minds or spirits, they inferred that the sun, moon, wind, tides and other moving entities were similarly animated. This primitive philosophy is called **animism** (from the Latin *animare*, 'to quicken, enliven, endow with breath or soul'). Even gravity was explained in animistic terms: rocks fell to the ground because the spirits within them wanted to be reunited with Mother Earth.

Obviously, animism is now of historical interest only. But note that different interpretations can be placed on the same events. Surely, we are just as prone to subjective interpretations of natural phenomena, albeit more sophisticated ones, as our ancestors were. In fact, when we try to explain why people do what they do, we tend to attribute at least some of their behaviour to the action of a motivating spirit – namely, a will. In our daily lives, this explanation of behaviour may often suit our needs. However, on a scientific level, we need to base our explanations on phenomena that can be observed and measured objectively. We cannot objectively and directly observe 'will'.

#### *Dualism: Ren Descartes*

Although the history of Western philosophy properly begins with the Ancient Greeks, a French philosopher and mathematician, René Descartes (1596–1650), is regarded as the father of modern philosophy. He advocated a sober, impersonal investigation of natural phenomena using sensory experience and human reasoning. He assumed that the world was a purely mechanical entity that, having once been set in motion by God, ran its course without divine interference. Thus, to understand the world, one had only to understand how it was constructed. This stance challenged the established authority of the Church, which believed that the purpose of philosophy was to reconcile human experiences with the truth of God's revelations.

Psychology: the development of a science 19

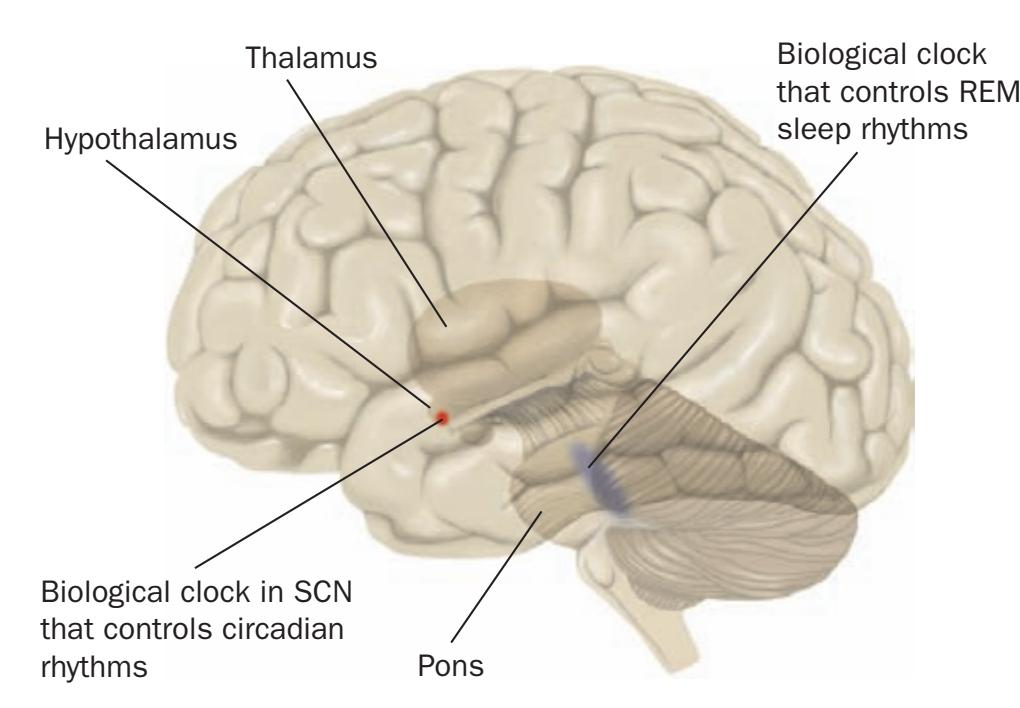

**Figure 1.2** Responses of a Finnish sample (*N* = 601) to four questions and statements about psychology. *Source*: Montin, S. The public image of psychologists in Finland. Reproduced with permission from *Psychology in Europe* by A. Schorr and S. Saari (eds), ISBN 0-88937-155-5, © 1995, Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Seattle, Toronto, Göttingen, Bern.

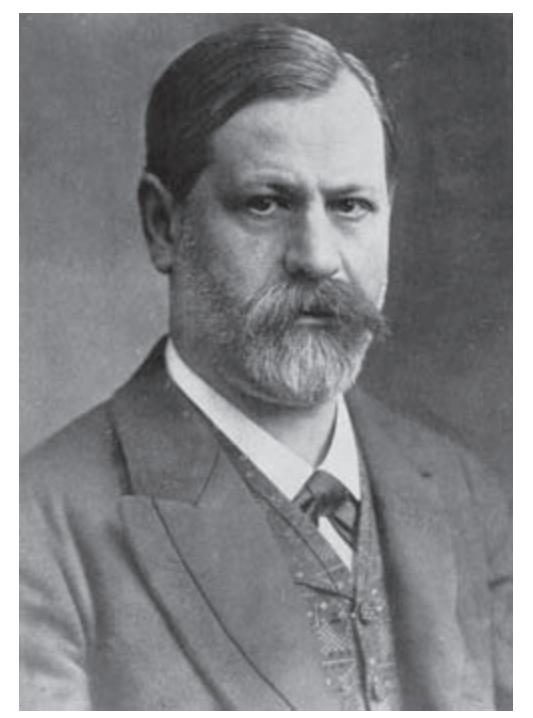

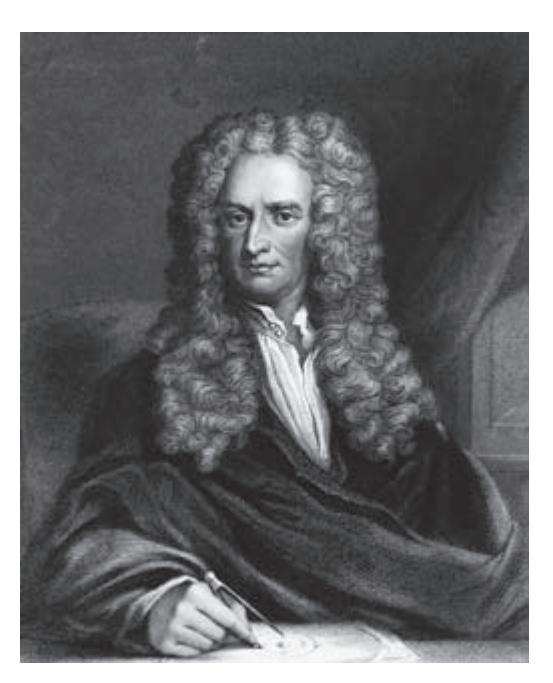

René Descartes (1596–1650). *Source*: Corbis: Chris Hellier.

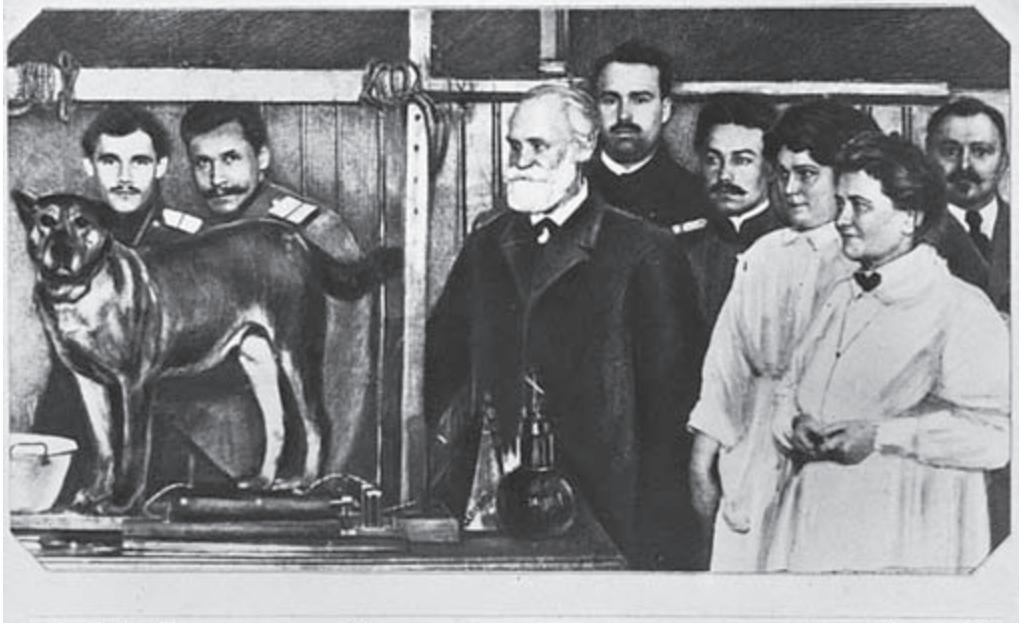

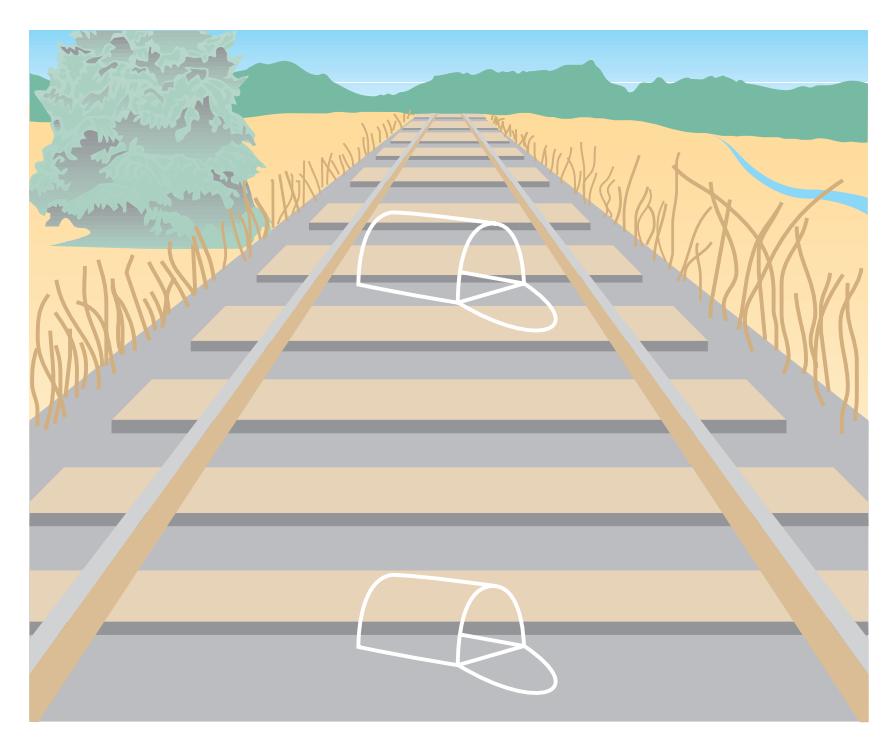

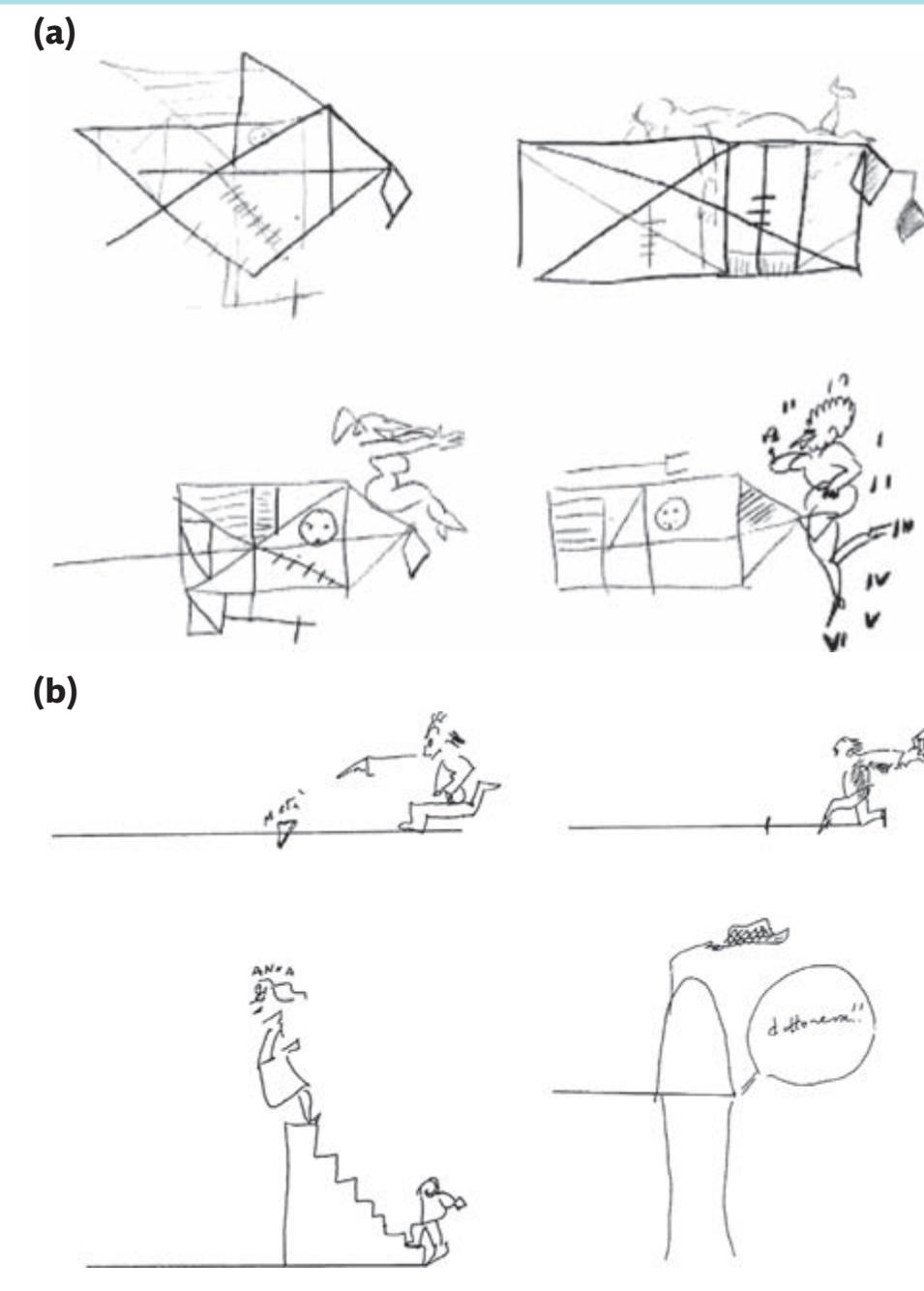

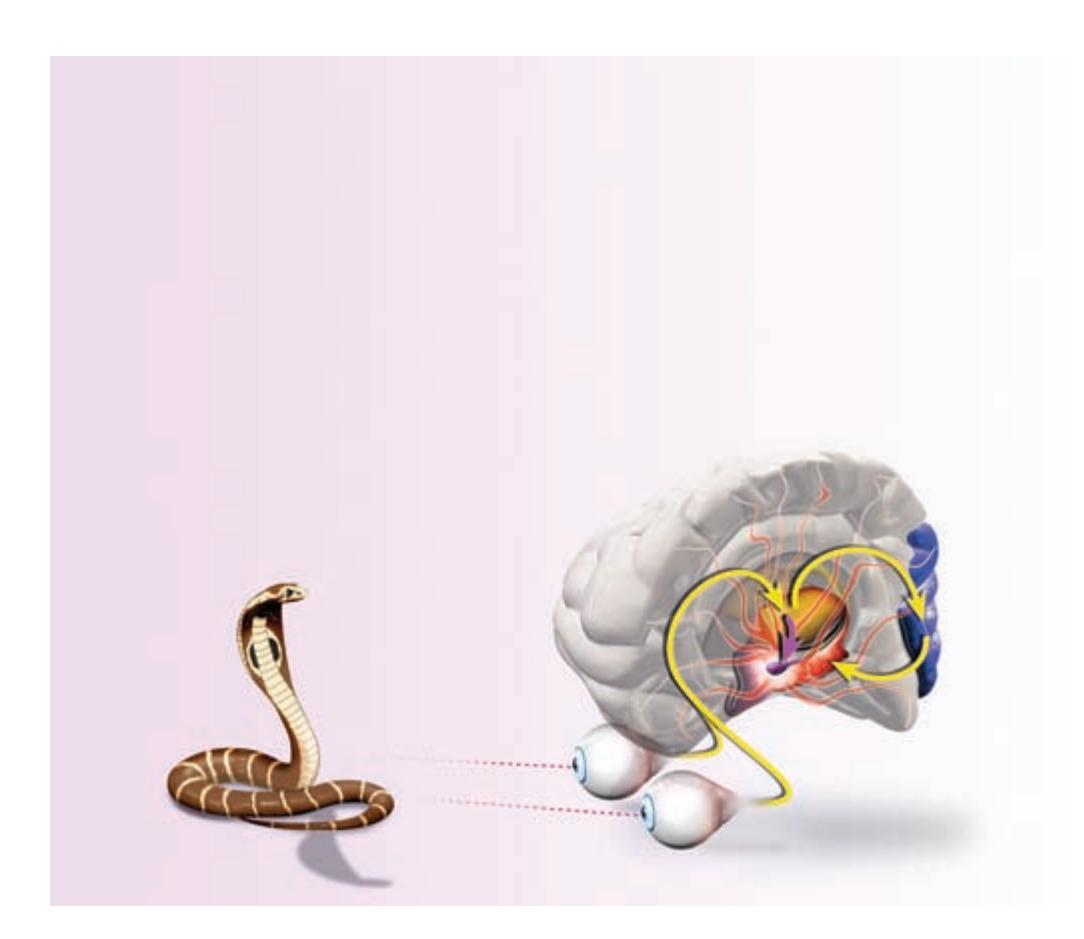

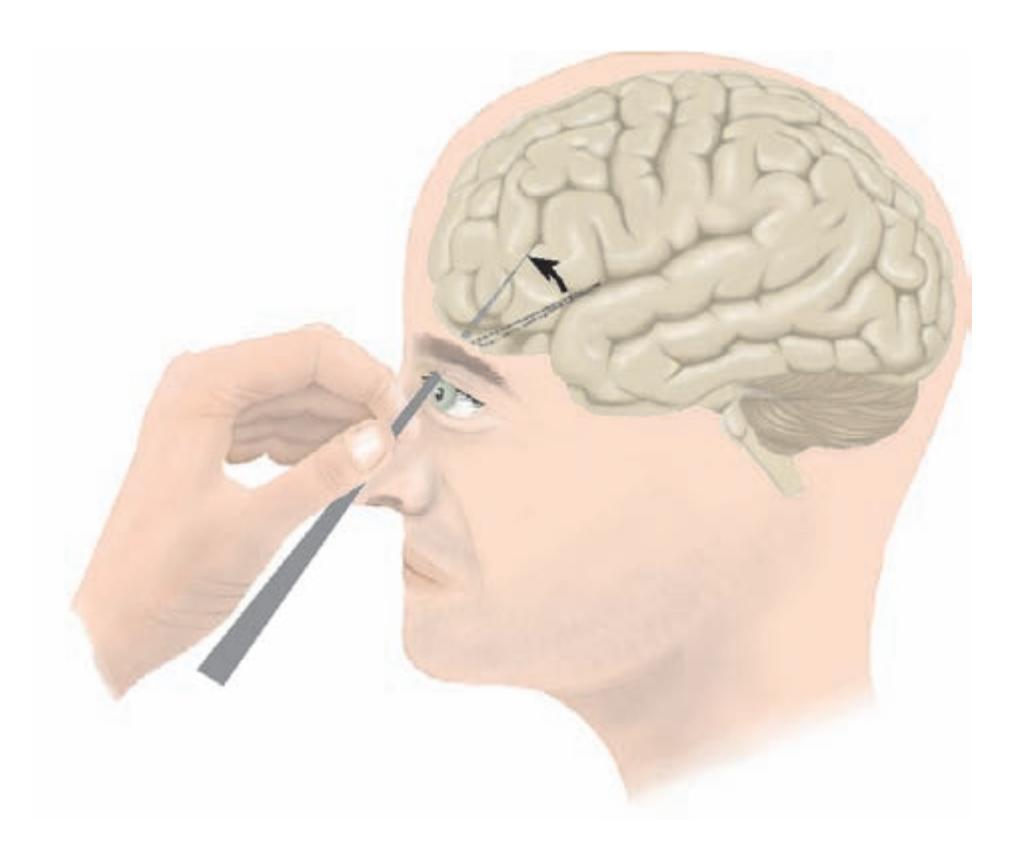

To Descartes, animals were mechanical devices; their behaviour was controlled by environmental stimuli. His view of the human body was much the same: it was a machine. Thus, Descartes was able to describe some movements as automatic and involuntary. For example, the application of a hot object to a finger would cause an almost immediate withdrawal of the arm away from the source of stimulation. Reactions like this did not require participation of the mind; they occurred automatically. Descartes called these actions **reflexes** (from the Latin *reflectere,* 'to bend back upon itself'). A stimulus registered by the senses produces a reaction that would be entirely physical and beyond voluntary control. There would be no intention or will to produce this physical reaction. Consider the well-known reflex of sensing the heat of a flame, as seen in Figure 1.3. The body recoils from flame in an involuntary way: we do not intentionally move away from the flame but our body reflexively puts in place a chain of muscle contractions which make us withdraw. The term 'reflex' is still in use today, but, of course, we explain the operation of a reflex differently (see Chapter 4).

What set humans apart from the rest of the world, according to Descartes, was their possession of a mind. This was a uniquely human attribute and was not

20 **Chapter 1** The science of psychology

**Figure 1.3** Descartes's diagram of a withdrawal reflex. *Source*: Stock Montage, Inc.

subject to the laws of the universe. Thus, Descartes was a proponent of **dualism**, the belief that all reality can be divided into two distinct entities: mind and matter (this is often referred to as **Cartesian dualism**). He distinguished between 'extended things', or physical bodies, and 'thinking things', or minds. Physical bodies, he believed, do not think, and minds are not made of ordinary matter.

Although Descartes was not the first to propose dualism, his thinking differed from that of his predecessors in one important way: he was the first to suggest that a link exists between the human mind and its purely physical housing. Although later philosophers pointed out that this theoretical link actually contradicted his belief in dualism - the proposal of an interaction between mind and matter - **interactionism**, was absolutely vital to the development of the science of psychology.

From the time of Plato onwards, philosophers had argued that the mind and the body were different entities. They also suggested that the mind could influence the body but the body could not influence the mind, a little like a puppet and puppeteer with the mind pulling the strings of the body. Not all philosophers adopted this view, however. To some, such as Spinoza (1632–1677), both mental events (thinking) and physical events (such as occupying space) were characteristic of one and the same thing, in the same way that an undulating line can be described as convex or concave – it cannot be described as exclusively one thing or another (this is called **double-aspect theory**).

Descartes hypothesised that this interaction between mind and body took place in the pineal body, a small organ situated at the top of the **brain stem**, buried beneath the large cerebral hemispheres of the brain. When the mind decided to perform an action, it tilted the pineal body in a particular direction, causing fluid to flow from the brain into the proper set of **nerves**. This flow of fluid caused the appropriate muscles to inflate and move.

How did Descartes come up with this mechanical concept of the body's movements? Western Europe in the seventeenth century was the scene of great advances in the sciences. This was the century, for example, in which William Harvey discovered that blood circulated around the body. It was not just the practical application of science that impressed Europeans, however, it was the beauty, imagination and fun of it as well. Craftsmen constructed many elaborate mechanical toys and devices during this period. The young Descartes was greatly impressed by the moving statues in the Royal Gardens (Jaynes, 1970) and these devices served as models for Descartes as he theorised about how the body worked. He conceived of the muscles as balloons. They became inflated when a fluid passed through the nerves that connected them to the brain and spinal cord, just as water flowed through pipes to activate the statues. This inflation was the basis of the muscular contraction that causes us to move.