# PSYCHOLOGY **DISCOVERING**

# PSYCHOLOGY **DISCOVERING**

SANDRA E. HOCKENBURY | SUSAN A. NOLAN | DON H. HOCKENBURY

**Seventh Edition**

Publisher: Rachel Losh

Executive Acquisitions Editor: Daniel McDonough

Developmental Editor: Marna Miller

Senior Marketing Manager: Lindsay Johnson

Marketing Assistant: Allison Greco Media Producer: Elizabeth Dougherty

Media Editor: Jessica Lauffer

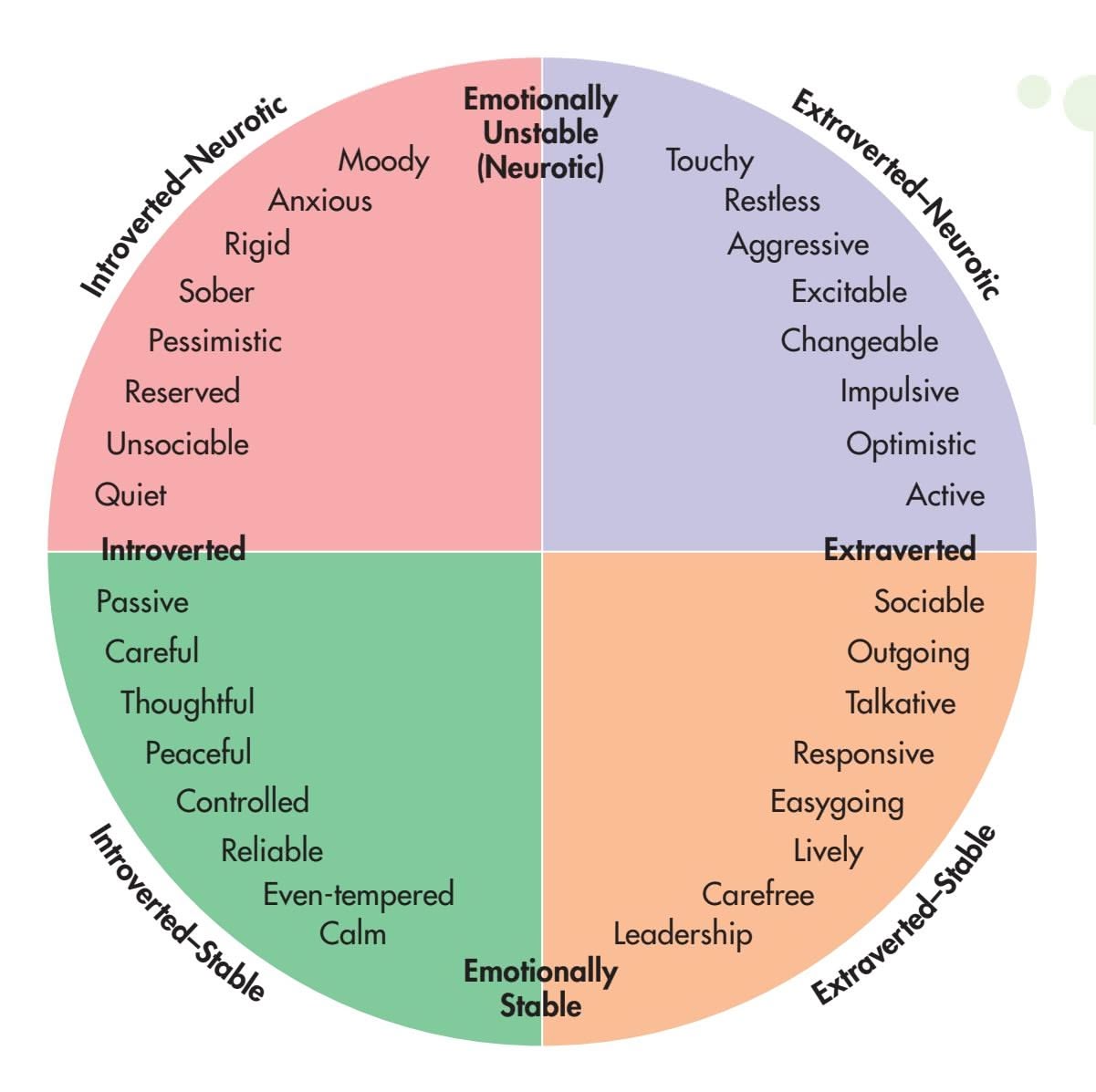

Editorial Assistant: Kimberly Morgan-Smith

Photo Editor: Christine Buese Photo Researcher: Jacquelyn Wong

Director, Content Management Enhancement: Tracey Kuehn

Managing Editor: Lisa Kinne

Project Editor: Ed Dionne, MPS North America LLC

Production Manager: Stacey B. Alexander

Art Director: Diana Blume Design Manager: Vicki Tomaselli

Cover and Interior Designer: Charles Yuen

Art Manager: Matthew McAdams

Art Illustrators: Todd Buck, Anatomical Art; TSI evolve

Composition: MPS Limited

Printing and Binding: RR Donnelley

Cover Photos: RGB Ventures/SuperStock/Alamy (background), Patrick Foto/

Getty Images (left), Image Source/Getty Images (right)

Library of Congress Preassigned Control Number: 2015955442

ISBN-13: 978-1-4641-7105-5 ISBN-10: 1-4641-7105-X

© 2016, 2014, 2011, 2007 by Worth Publishers

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

First printing

Worth Publishers One New York Plaza [Suite 4500](http://www.worthpublishers.com) New York, NY 10004-1562 www.worthpublishers.com

Hockenbury\_7e\_FM\_Printer.indd 4 04/12/15 12:19 PM

# B[RIEF CO](#page--1-0)NTENTS

To the Instructor xx

[To the Student: Learning from](#page-11-0) *Discovering Psychology* xlviii

INTRODUCING PSYCHOLOGY CHAPTER 1[Introduction and Researc](#page-51-0)h Methods 1 [PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL PROCESSES](#page-95-0) CHAPTER 2 [Neuroscience and Behavior](#page-143-0) 40 CHAPTER 3 Sensation and Perception 84 CHAPTER 4 [Consciousness a](#page-191-0)nd Its Variations 132 [BASIC PSYCHOLOG](#page-237-0)ICAL PROCESSES CHAPTER 5 [Learning](#page-281-0) 180 CHAPTER 6 [Memory](#page-323-0) 226 CHAPTER 7 Thinking, Language, and Intelligence 270 CHAPTER 8 [Motivation and Emo](#page-367-0)tion 312 [THE DEVELOPMENT O](#page-423-0)F THE SELF CHAPTER 9 Lifespan Development 356 CHAPTER 10 [Personality](#page-463-0) 412 THE PERSON IN SOCIAL CONTEXT CHAPTER 11 [Social Psychology](#page-507-0) 452 [PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS, DISORD](#page-543-0)ERS, AND TREATMENT [CHAPTER 12](#page-595-0) Stress, Health, and Coping 496 CHAPTER 13 Psychological Disorders 532 CHAPTER 14 [Therapies](#page-641-0) 584 APPENDIX A Statistics: Understanding Data A-1 APPENDIX B[Indust](#page--1-0)rial/Organizational Psychology B-1 [Glossary](#page--1-0) G-1 [References](#page--1-0) R-1 Name Index NI-1 Subject Index SI-1 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 SECTION 3 SECTION 4 SECTION 5 SECTION 6

The following is a list of common data types:

- Integer

- Float

- String

- Boolean

- List

- Dictionary

Here is an example of a dictionary:

`python

my_dict = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "New York"}`

And here is an example of a list:

`python

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]`

This is a simple example of how data types can be used in programming.

vii

Hockenbury\_7e\_FM\_Printer.indd 7 04/12/15 12:19 PM

# TO THE [STUDENT](#page--1-0)

# Learning from *Discovering Psychology*

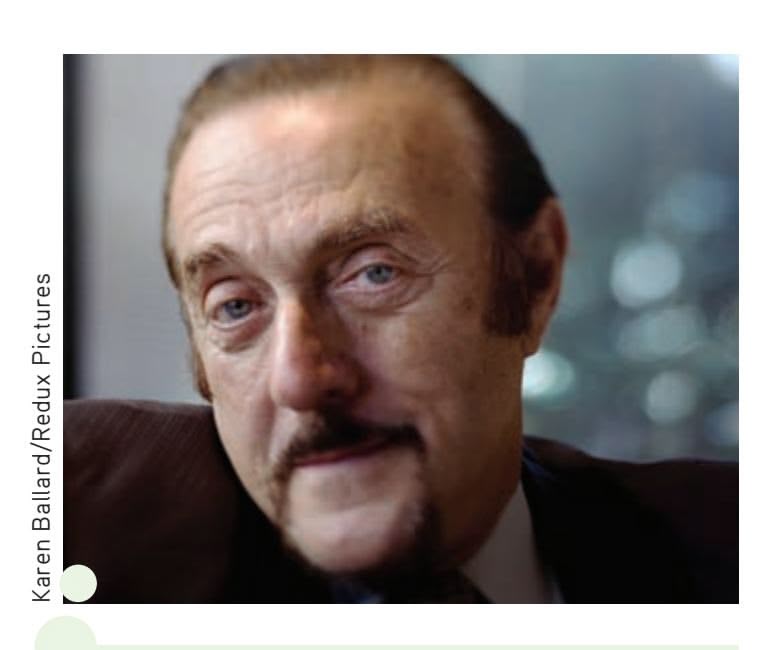

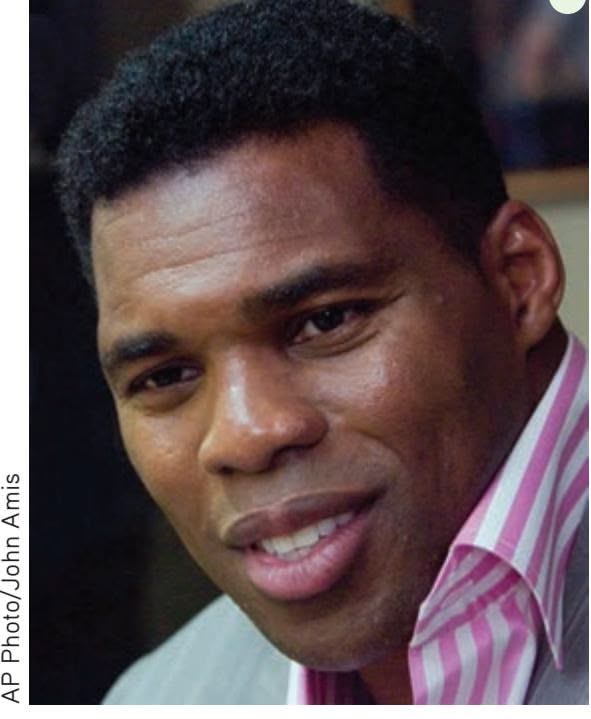

Welcome to psychology! Our names are **Sandy Hockenbury, Susan Nolan,** and **Don Hockenbury**, and we're the authors of your textbook. Every semester, we teach several sections of introductory psychology. We wrote this text to help you succeed in the class you are taking. Every aspect of this book has been carefully designed to help you get the most out of your introductory psychology course. Before you begin reading, you will find it well worth your time to take a few minutes to familiarize yourself with the special features and learning aids in this book.

## Learning Aids in the Text

## KEY THEME

You can enhance your chances for success in psychology by using the learning aids that have been built in to this textbook.

#### KEY QUESTIONS

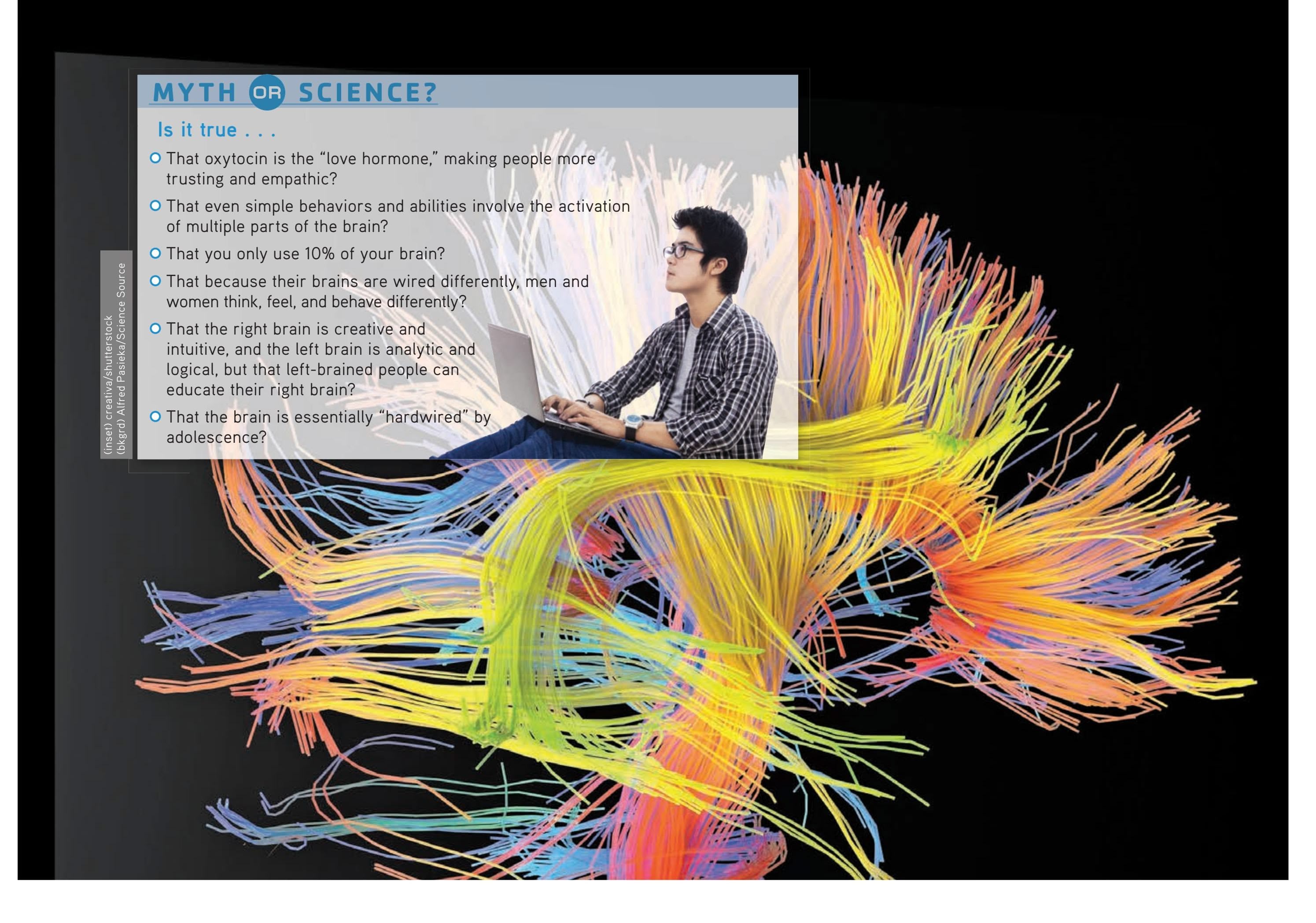

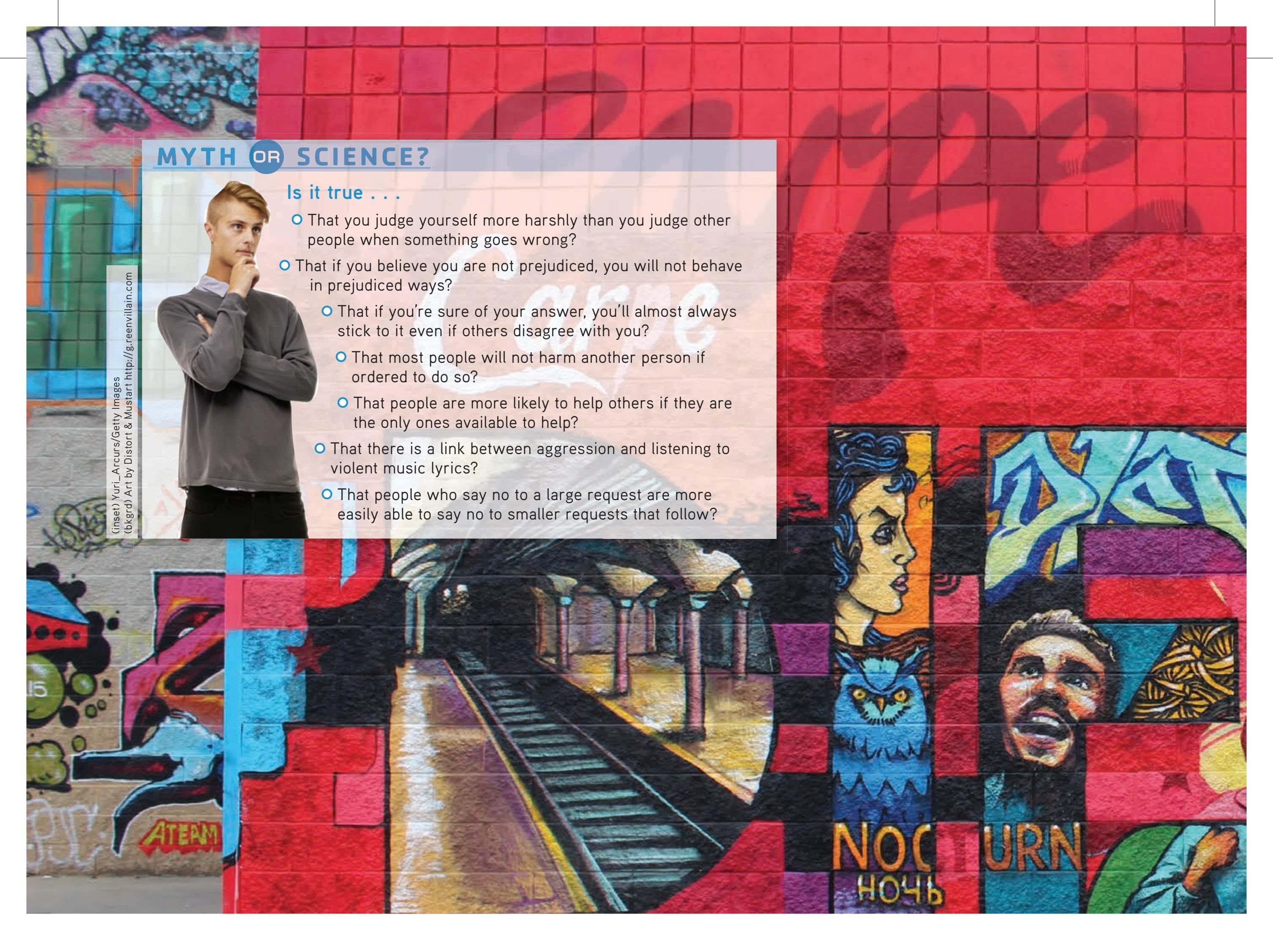

- ❯ What are the functions of the Prologue, "Myth or Science?" questions, Advance Organizers, Key Terms, Key People, and Concept Maps?

- ❯ What are the functions of the different types of boxes in this text, and why should you read them?

- ❯ Where can you go to access a virtual study guide at any time of the day or night, and what study aids are provided?

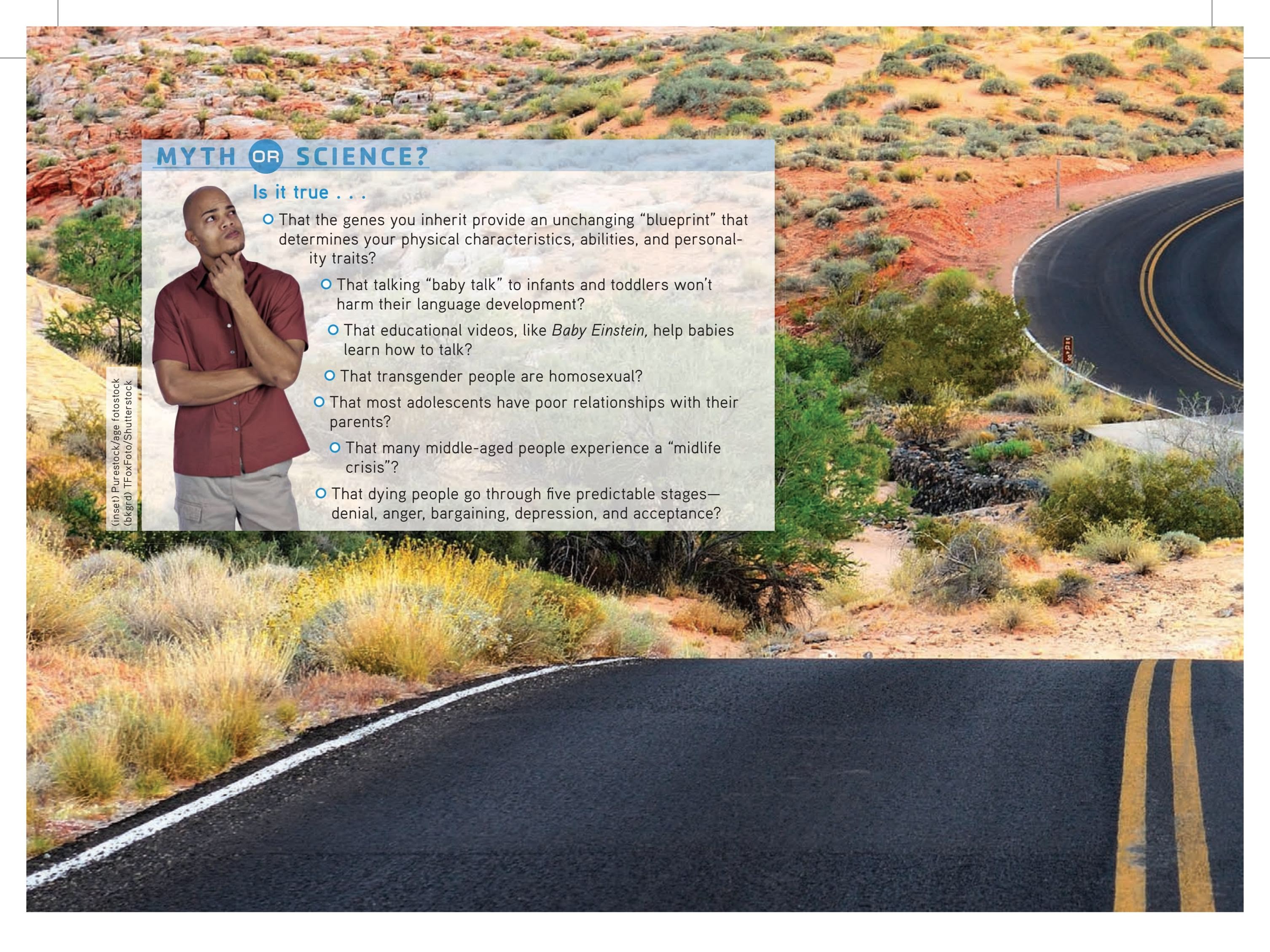

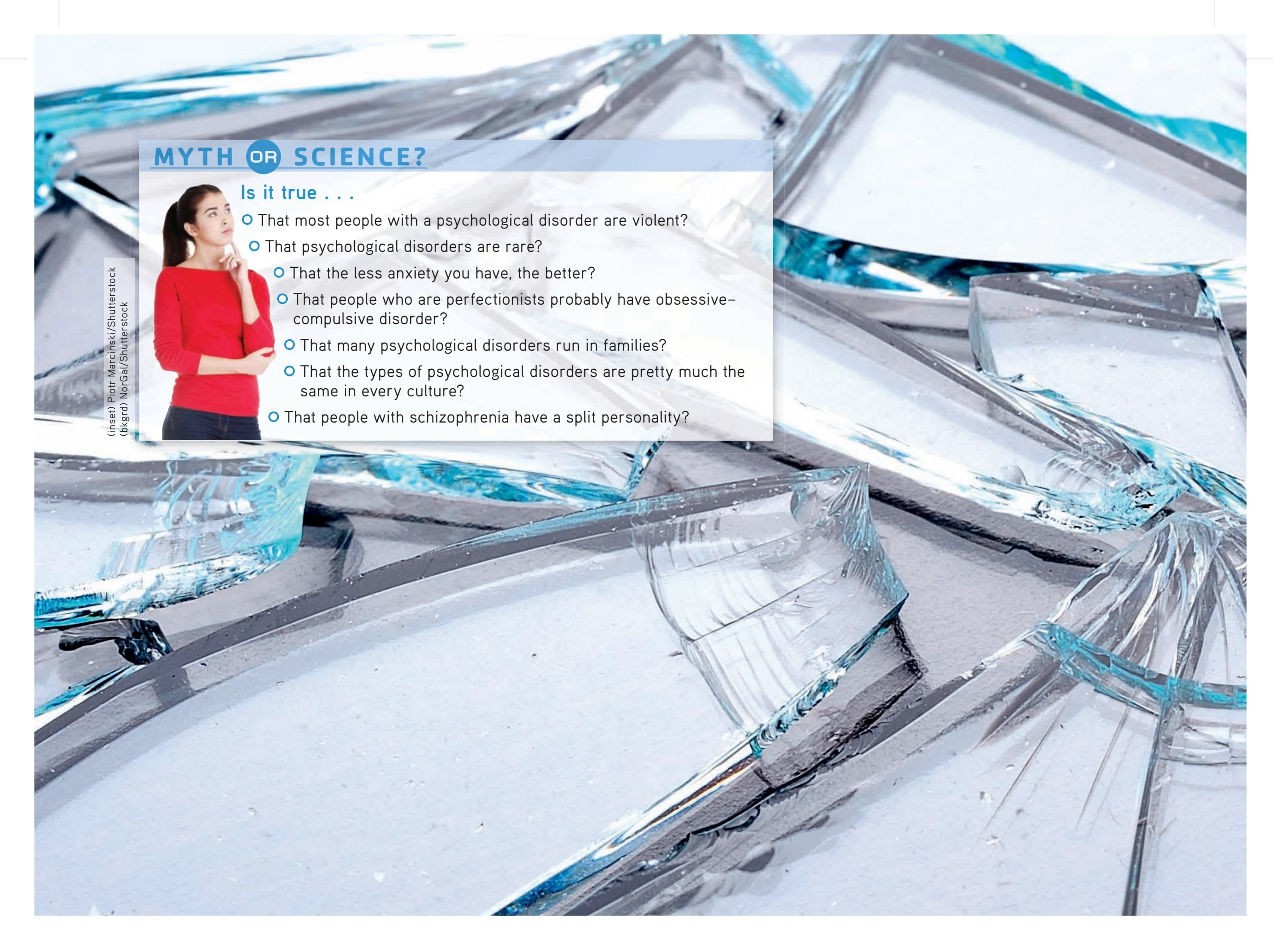

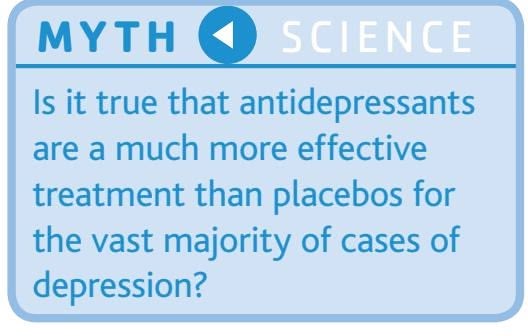

First, read and think about the "Myth or Science?" questions at the beginning of each chapter. These questions reflect common ideas about some of the topics we'll cover. How many of these statements have you heard before? In the course of reading the chapter you'll find out which statements are popular myths—and which are actually true and based on scientific evidence.

Next, take a look at the **Chapter Outline** at the beginning of each chapter. The Chapter Outline provides an overview of the main topics that will be covered in the chapter. You might also want to flip through the chapter and browse a bit so you have an idea of what's to come.

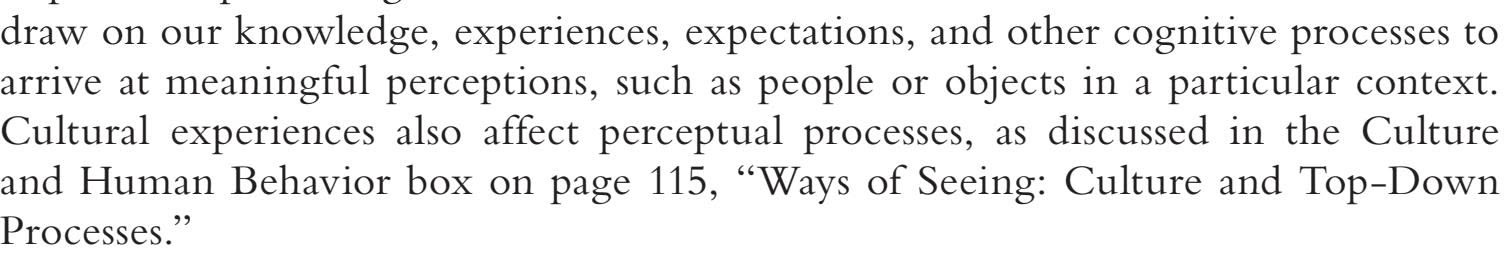

Then, read the chapter **Prologue.** The Prologues are true stories about real people. Some of the stories are humorous, some dramatic. We think you will enjoy this special feature, but it will also help you to understand the material in the chapter that follows and why the topics are important and relevant to your life. In each chapter, we return to the people and stories introduced in the Prologue to illustrate important themes and concepts.

As you begin reading the chapter, you will notice several special elements. **Major Sections** are easy to identify because the heading is in blue type. The beginning of each major section also includes an **Advance Organizer**—a short section preview that looks like the one above.

The **Key Theme** provides you with a preview of the material in the section to come. The **Key Questions** will help you focus on some of the most important material in the section. Keep the questions in mind as you read the section. They will help you identify important points in the chapter. After you finish reading each section, look again at the Advance Organizer. Make sure that you can confidently answer each question before you go on to the next section. If you want to maximize your understanding of the material, write out the answer to each question. You can also use the questions in the Advance Organizer to aid you in taking notes or in outlining chapter sections, both of which are effective study strategies.

**James** A young man living in a rural area in upstate New York, James is an avid gardener, writer, and artist. He's a volunteer and an activist in his community. He's also transgender. James wants people to realize that there are many parts of his identity as a person. He told your author Susan that people "shouldn't really be focused on this term transgender because a lot of people seem to stick us in a category." He wants people to see beyond the label and get to know him as a person.

xlviii

Hockenbury\_7e\_FM\_Printer.indd 48 04/12/15 12:21 PM

To the Student xlix

Worth Publishers

Notice that some terms in the chapter are printed in **boldface,** or darker, type. Some of these key terms may already be familiar to you, but most will be new. The darker type signals that the term has a specialized meaning in psychology. Each key term is formally defined within a sentence or two of being introduced. The key terms are also defined in the margins, usually on the page on which they appear in the text. Some key terms include a **pronunciation guide** to help you say the word correctly.

Occasionally, we print words in *italic type* to signal either that they are boldfaced terms in another chapter or that they are specialized terms in psychology.

Certain names also appear in boldface type. These are the **key people**—the researchers or theorists who are especially important within a given area of psychological study. Typically, key people are the psychologists or other researchers whose names your instructor will expect you to know.

You'll also notice notations at the end of major sections inviting you to ❯ Test your understanding with . This notation signals that the material you have just finished reading is covered by a comprehensive quiz in Launch-Pad. (You can find instructions on how to access LaunchPad in the section titled "LaunchPad for *Discovering Psychology,* Seventh Edition" on the next page.)

In the margins of every chapter, you will find callouts directing you to LaunchPad activities. Some of these LaunchPad activities expand upon topics introduced in the text, while others will help you review and better comprehend the text's information. Many of the activities incorporate video footage or simulations, but all of them were chosen for their relevance to the chapter material.

Also in LaunchPad are the **Think Like a Scientist** Immersive Learning Activities. These activities were created by your authors to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. This special feature provides an interactive, fun, and interesting activity to apply what you've learned to a new topic or claim. Whenever you see a *Think Like a Scientist* callout in the margin of your textbook, check out the activity to explore questions like "Can you learn to tell when someone is lying?" and "Do you have psychic powers?"

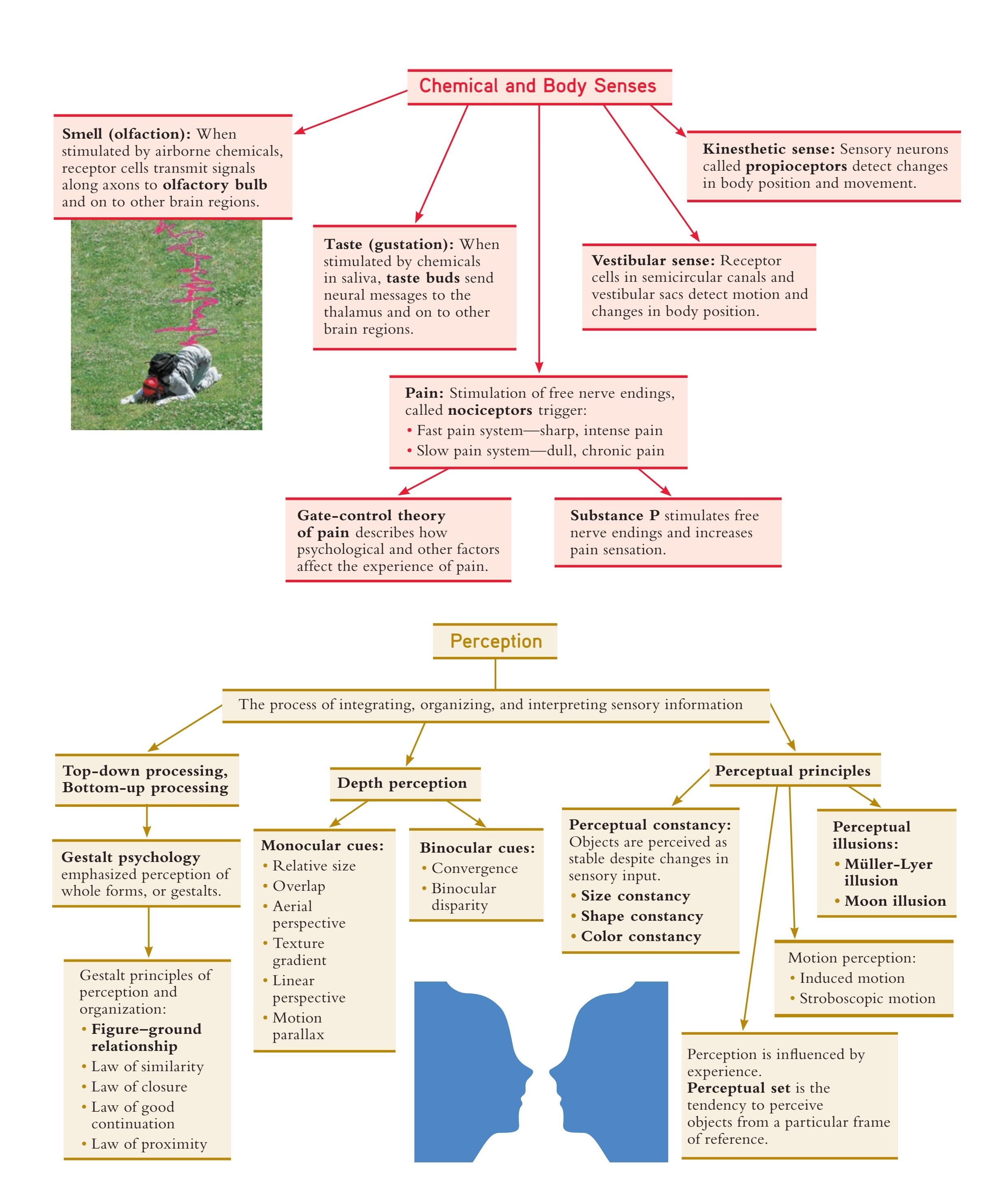

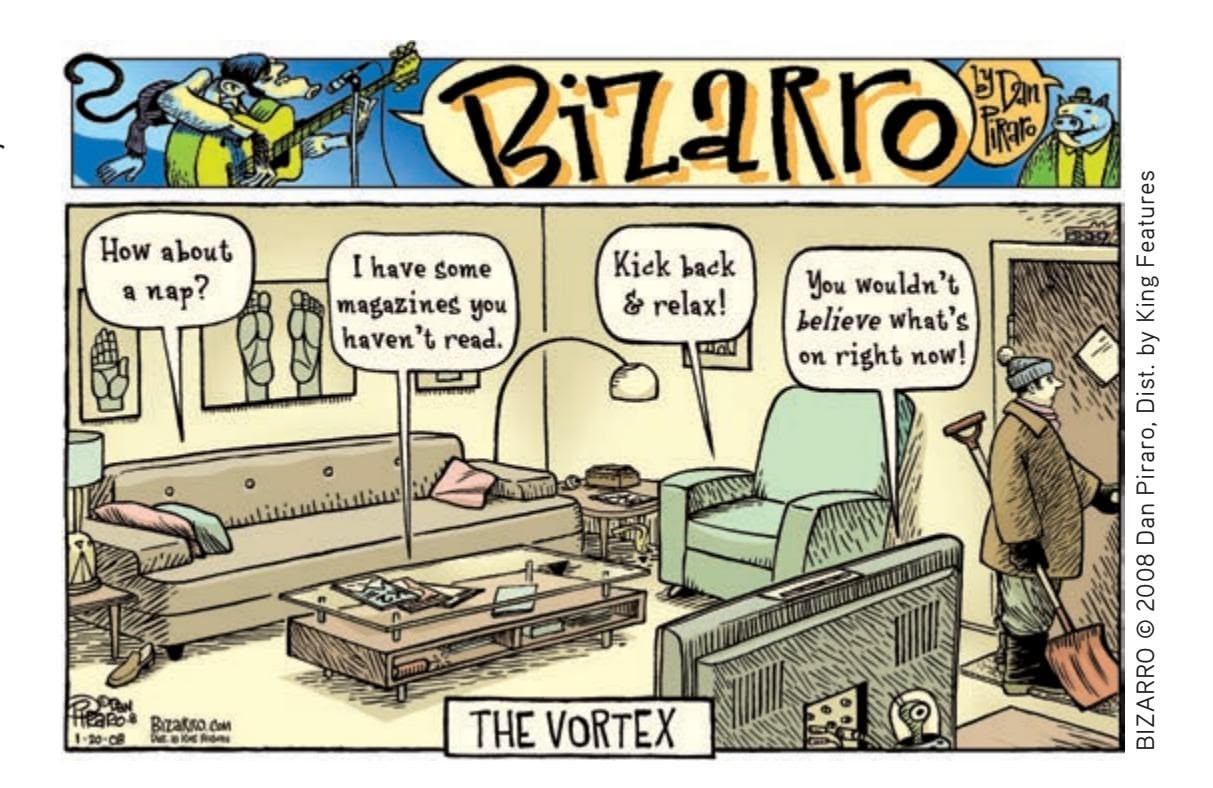

## Reviewing for Examinations

The **Chapter Review** at the end of each chapter includes several elements to help you review what you have learned. All the chapter's **key people** and **key terms** are listed, along with the pages on which they appear and are defined. The key terms are also boldfaced in the chapter summary so you can see their use in context. You can check your knowledge of the key people by describing in your own words why each scientist is important. You will also want to define each key term in your own words, then compare your definition to information on the page where it is discussed. The visual **Concept Maps** at the end of the chapter give you a hierarchical layout showing how themes, concepts, and facts are related to one another. The photos in each Concept Map should provide additional visual cues to help you consolidate your memory of important chapter information. Use the visual Concept Maps to review the information in each section.

## Special Features in the Text

Each chapter in *Discovering Psychology* has several boxes that focus on different kinds of topics. Take the time to read the boxes because they are an integral part of each chapter. They also present important information that you may be expected to know for class discussion or tests. There are five types of boxes:

• **Critical Thinking** boxes ask you to stretch your mind a bit by presenting issues that are provocative or controversial. They will help you actively question the implications of the material that you are learning.

Think you're good at paying attention? Try **Video Activity: Attention.**

Can you learn to tell when someone is lying? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to **Think Like a Scientist** about **Lie Detection.**

l To the Student

- • **Science Versus Pseudoscience** boxes examine the evidence for various popular pseudosciences—from subliminal persuasion to *Baby Einstein* videos and graphology. These discussions will help teach you how to think scientifically and to critically evaluate claims in many different fields—not just psychology.

- • **Culture and Human Behavior** boxes are another special feature of this text. Many students are unaware of the importance of cross-cultural research in contemporary psychology. These boxes highlight cultural differences in thinking and behavior. They will also sensitize you to the ways in which people's behavior, including your own, has been influenced by cultural factors.

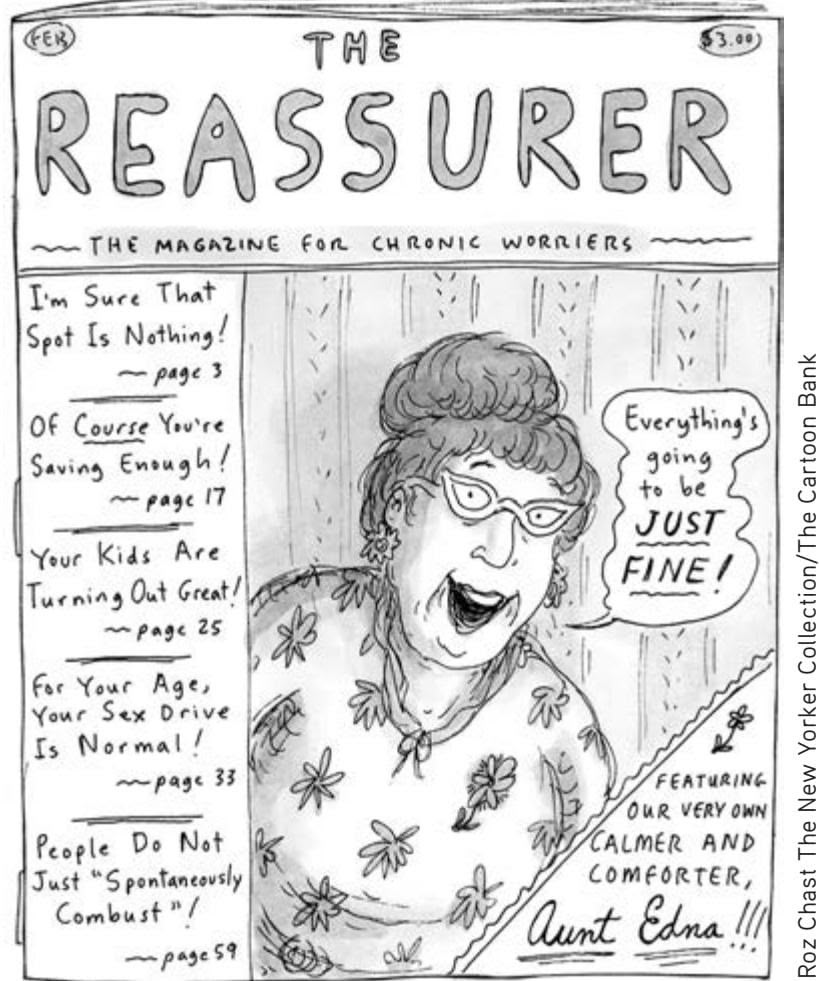

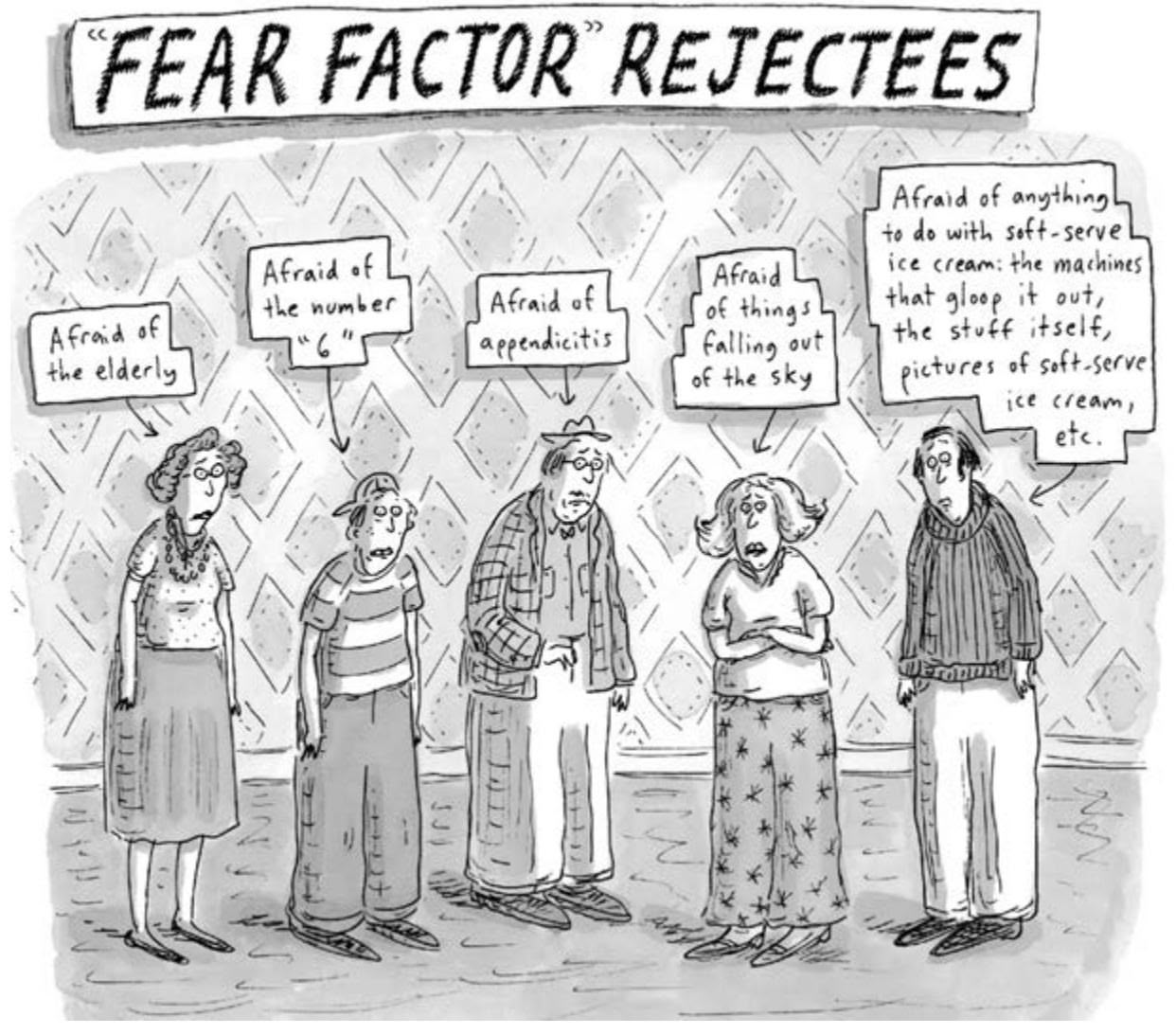

- • **In Focus** boxes present interesting information or research. Think of them as sidebar discussions. They deal with topics as diverse as human pheromones, whether animals dream, and why snakes and spiders give so many people the creeps.

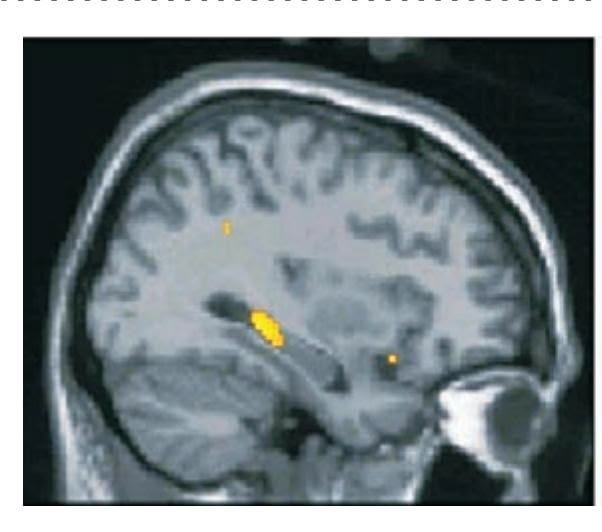

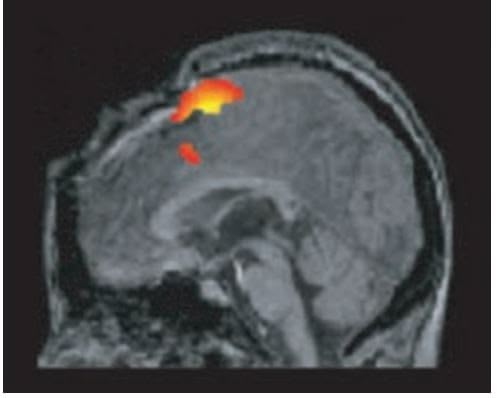

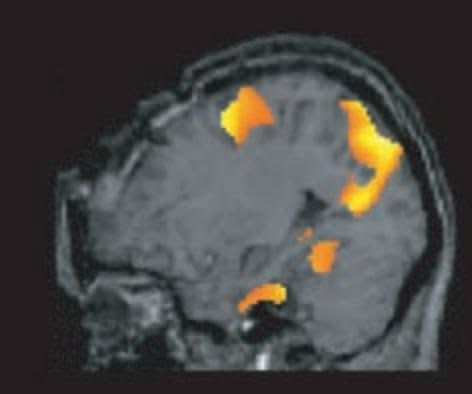

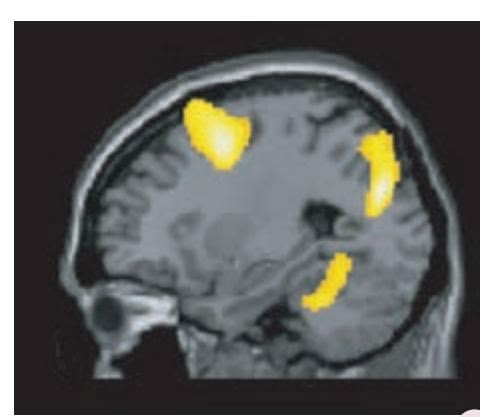

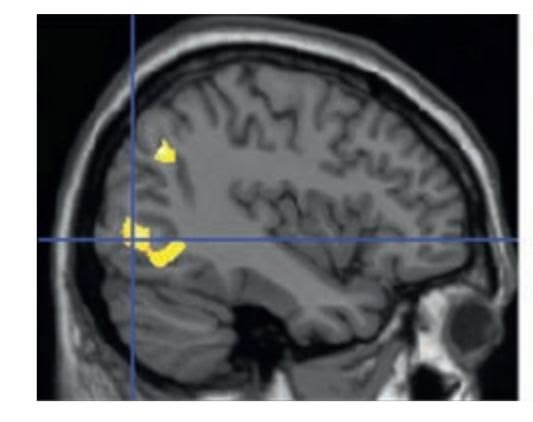

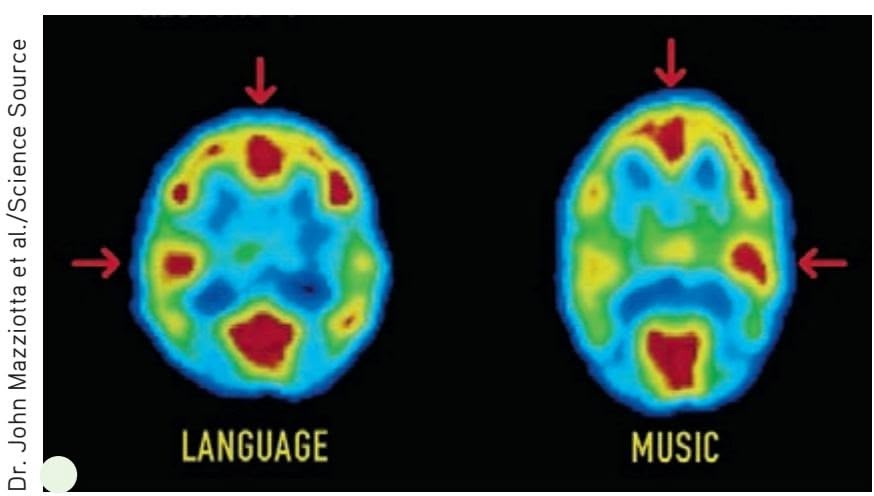

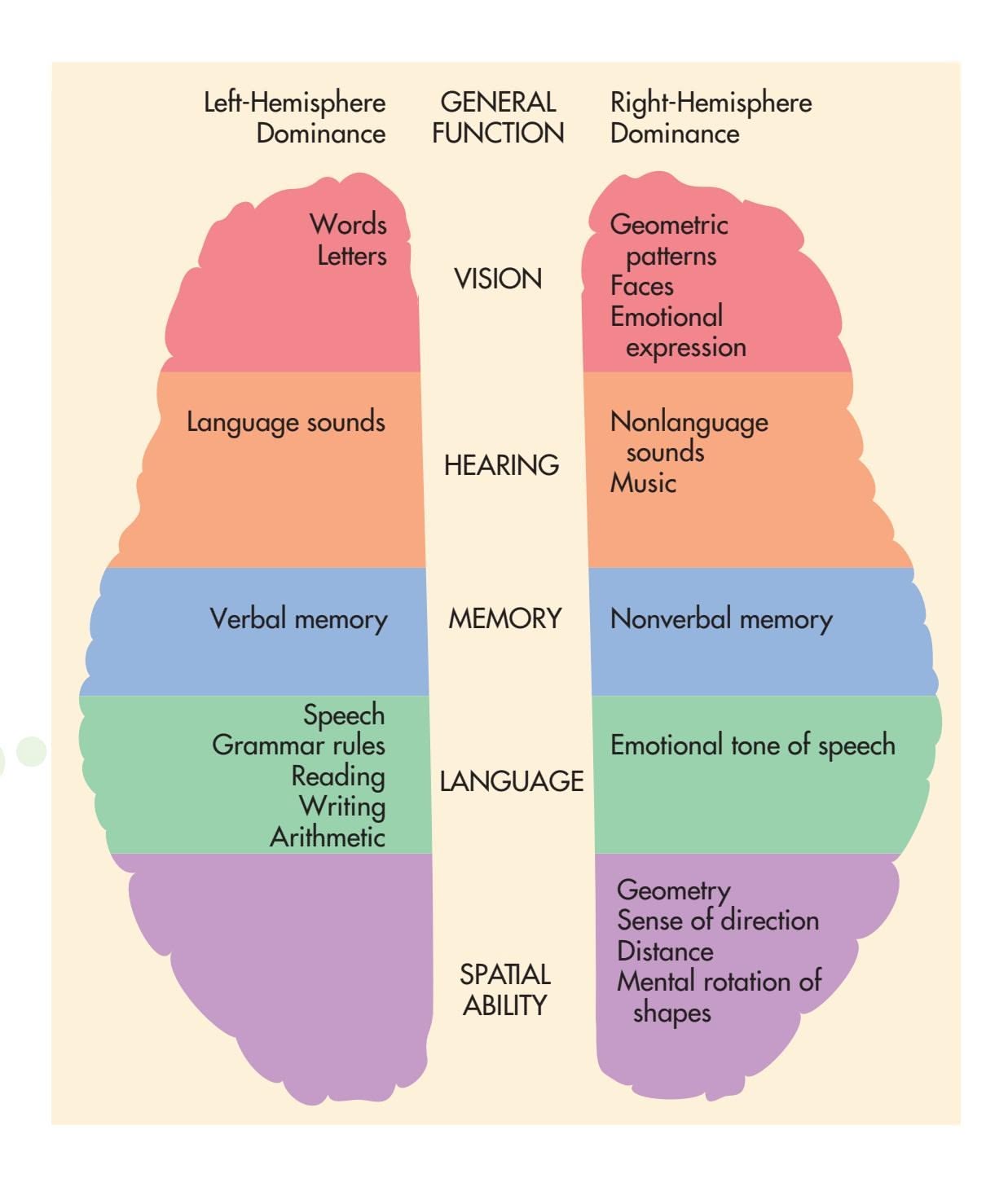

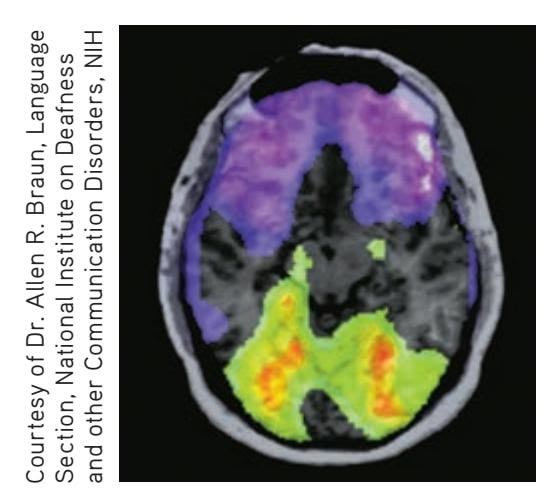

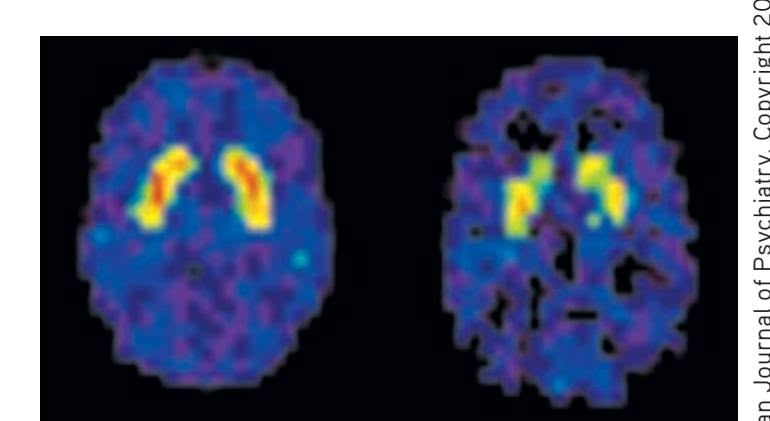

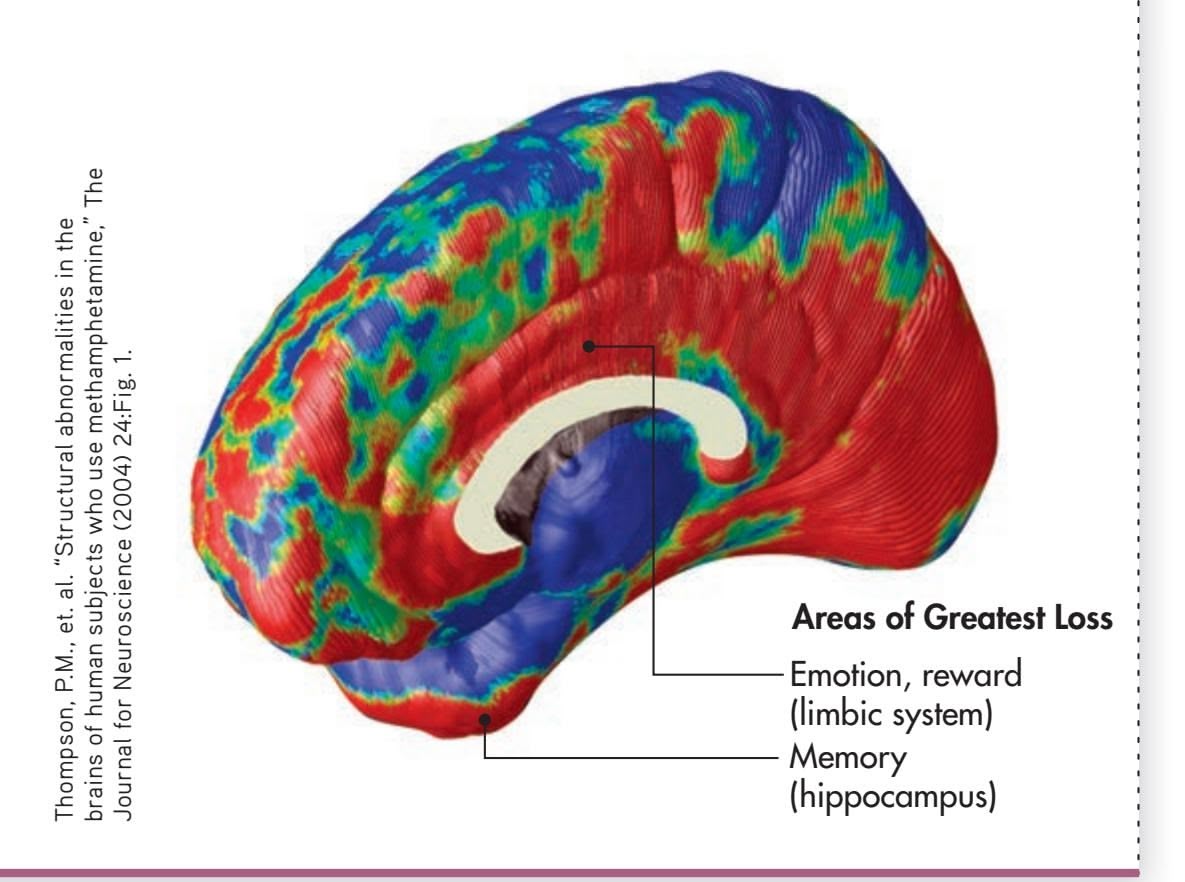

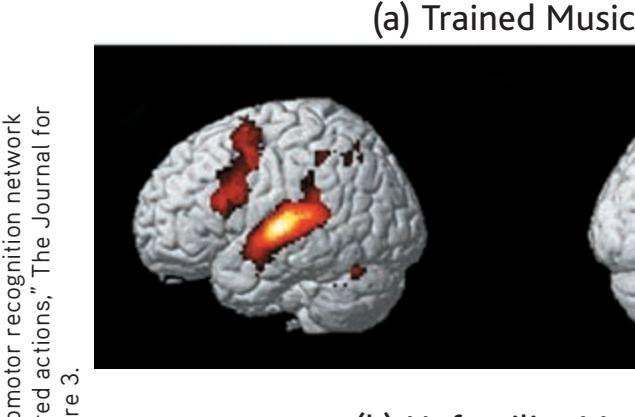

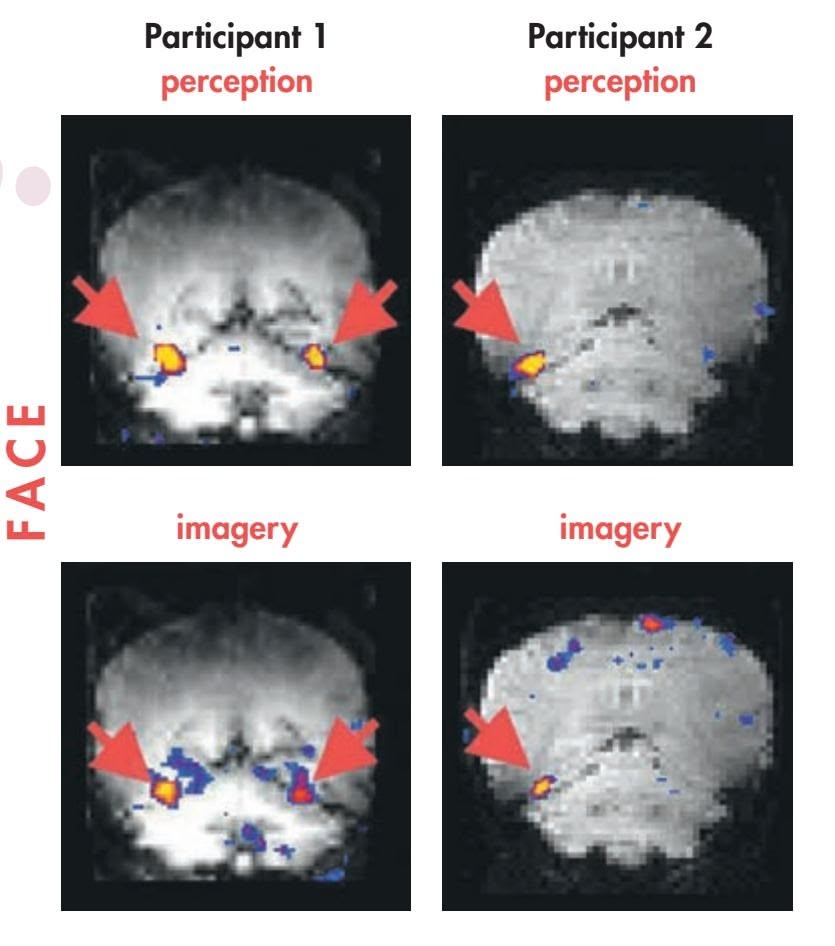

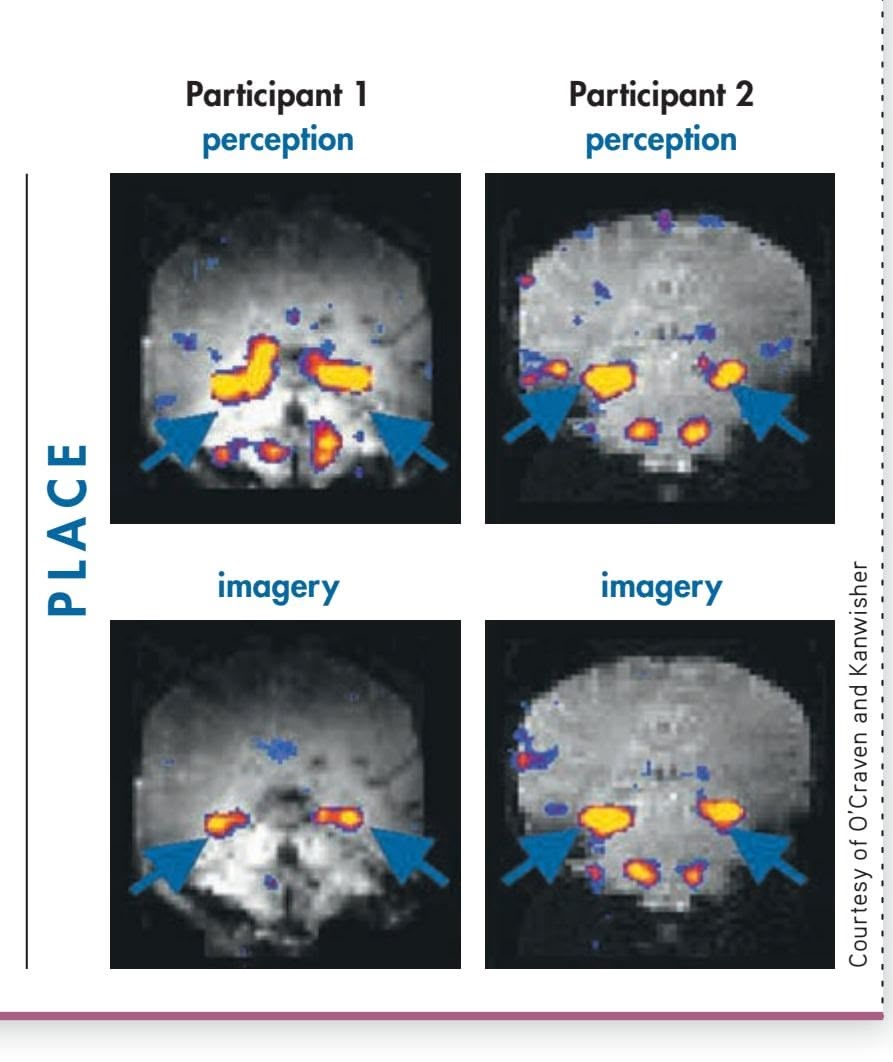

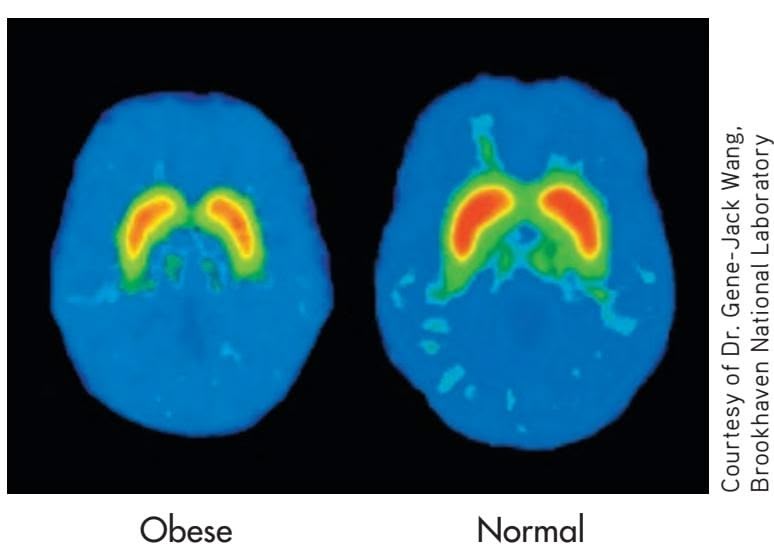

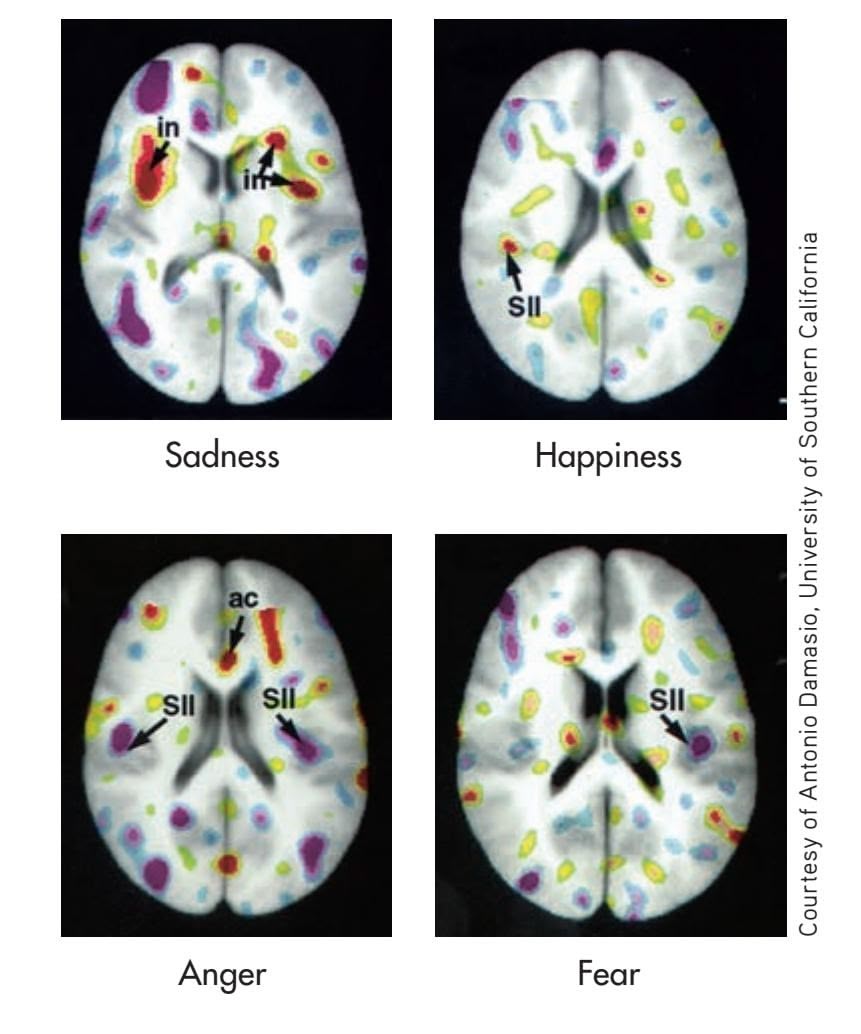

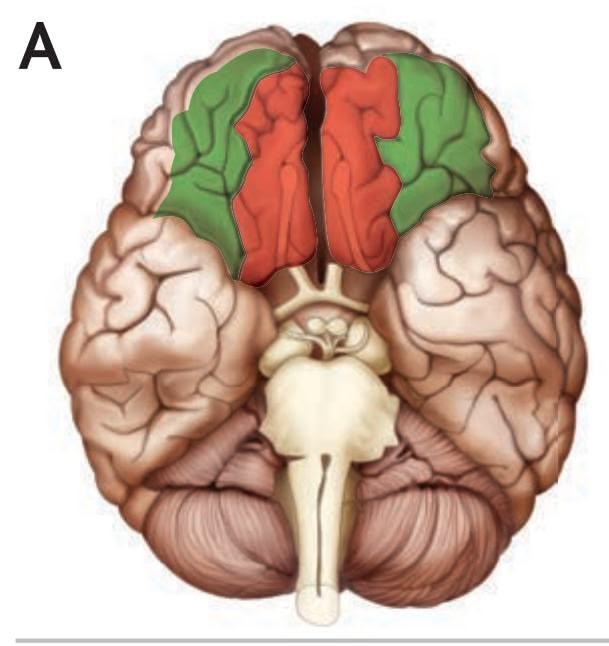

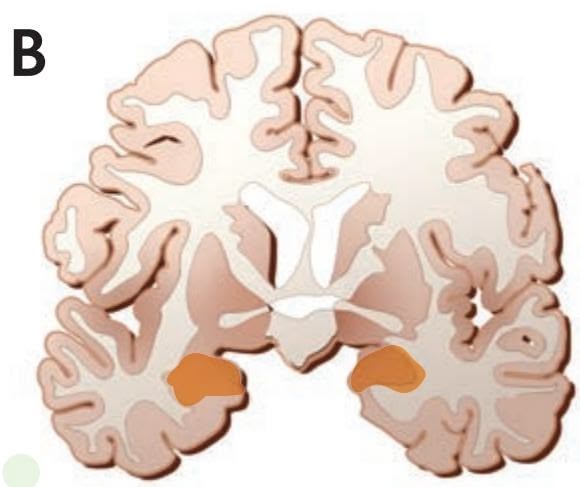

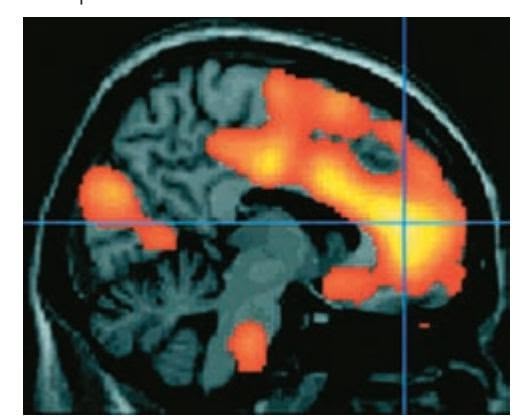

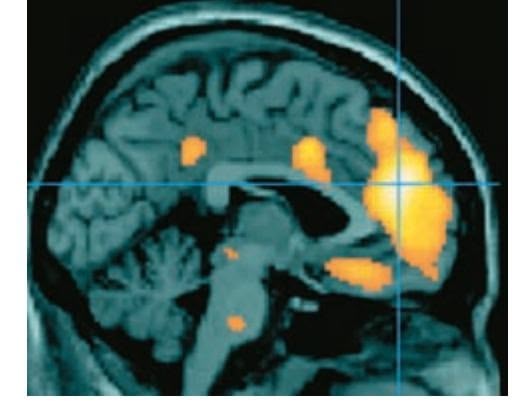

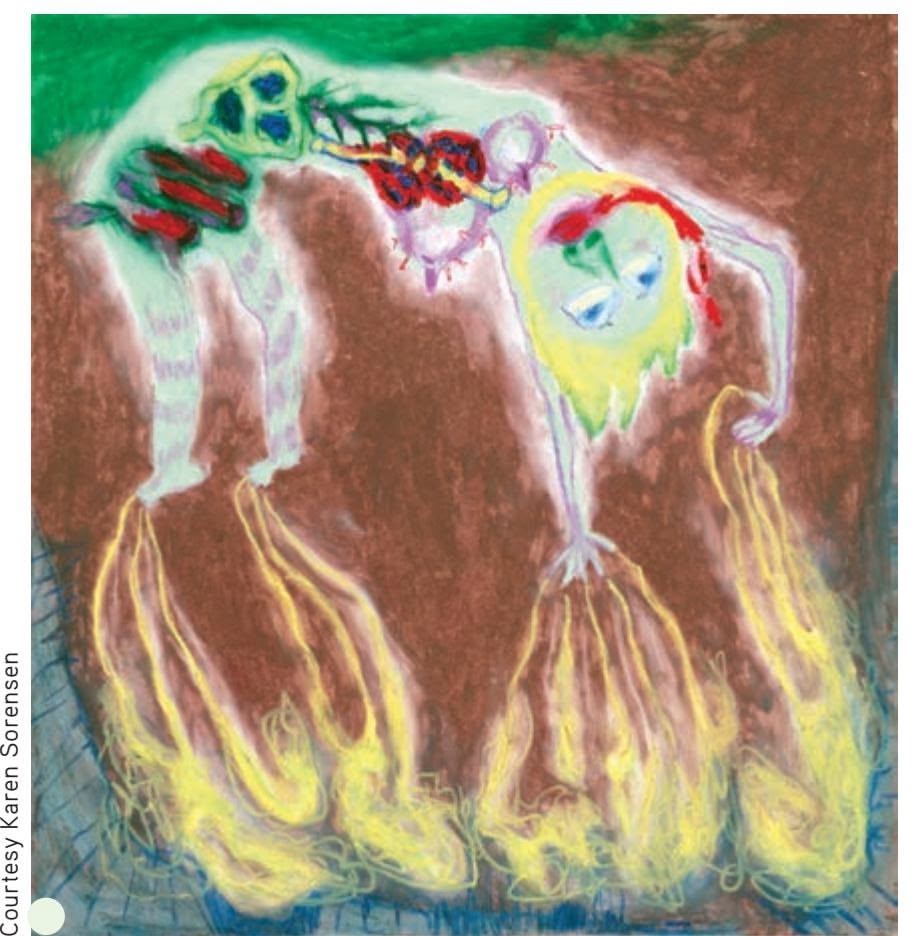

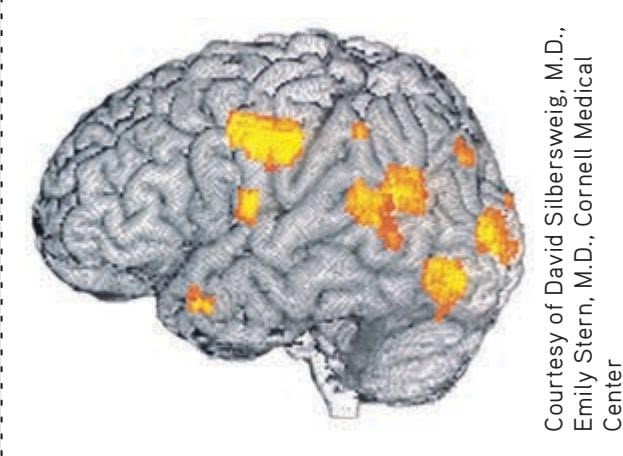

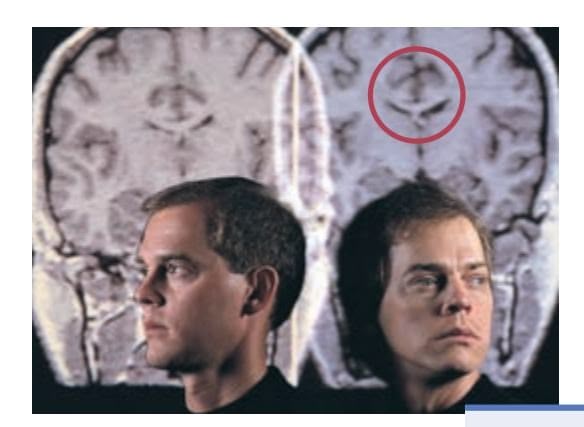

- • **Focus on Neuroscience** sections provide clear explanations of intriguing studies that use brain-imaging techniques to study psychological processes. Among the topics that are highlighted: schizophrenic hallucinations, mental images, drug addiction, and romantic love and the brain.

The **Psych for Your Life** section at the end of each chapter provides specific suggestions to help apply chapter information to help you deal with real-life concerns. These suggestions are based on psychological research, rather than opinions, anecdotes, or pop psych self-help philosophies.

Especially important is the Psych for Your Life section at the end of Chapter 1, which provides a list of research-based study techniques that you can use to help you succeed in psychology and other courses as well. In addition, the Psych for Your Life sections for Chapters 5, 6, and 8 deal with setting and achieving goals and enhancing motivation and memory, so you may want to skip ahead and read them after you finish this To the Student section. We hope that all of the Psych for Your Life sections make a difference in your life.

There are two special appendices at the back of the text. The **Statistics: Understanding Data** appendix discusses how psychologists use statistics to summarize and draw conclusions from the data they have gathered. The **Industrial/Organizational Psychology** appendix describes the branch of psychology that studies human behavior in the workplace. Your instructor may assign one or both of these appendices, or you may want to read them on your own.

Also at the back of this text is a **Glossary** containing the definitions for all **key terms** in the book and the pages on which they are discussed in more detail. You can use the **Subject Index** to locate discussions of particular topics and the **Name Index** to locate particular researchers. Finally, interested students can look up the specific studies we cite in the **References** sections.

### LAUNCHPAD FOR *DiScovering PSychoLogy,* SEVENTH EDITION

Get the most out of *Discovering Psychology,* Seventh Edition, with **LaunchPad,** which combines an interactive e-Book with high-quality multimedia content and activities that give you immediate feedback on your performance. Throughout the book you will see callouts that signal you to go to LaunchPad to access this online content.

- • **Fully Interactive e-Book:** The LaunchPad e-Book for *Discovering Psychology,* Seventh Edition, comes with powerful study tools. You can search, highlight, and bookmark, making it easier to study.

- • **Multimedia Content:** Access videos, simulations, tutorials, and *Think Like a Scientist* activities that help you understand and master the material.

- • **LearningCurve:** These game-like quizzes adapt to what you already know and help you master the concepts you need to learn.

To the Student li

To learn more about LaunchPad for *Discovering Psychology,* Seventh Edition, or to request access, go to **launchpadworks.com**.

That's it! We hope you enjoy reading and learning from the seventh edition of *Discovering Psychology.* If you want to share your thoughts or suggestions for the next edition of this book, you can write to us at the following address:

Sandy Hockenbury, Susan Nolan, and Don Hockenbury c/o Worth Publishers One New York Plaza Suite 4500 [New York, NY 10004-1562](mailto:Hockenbury.Psychology@gmail.com)

Or you can contact us at our e-mail address:

**Hockenbury.Psychology@gmail.com**

Have a great semester!

Hockenbury\_7e\_FM\_Printer.indd 51 04/12/15 12:21 PM

## [THE FIRST EX](#page--1-0)AM

## **PROLOGUE**

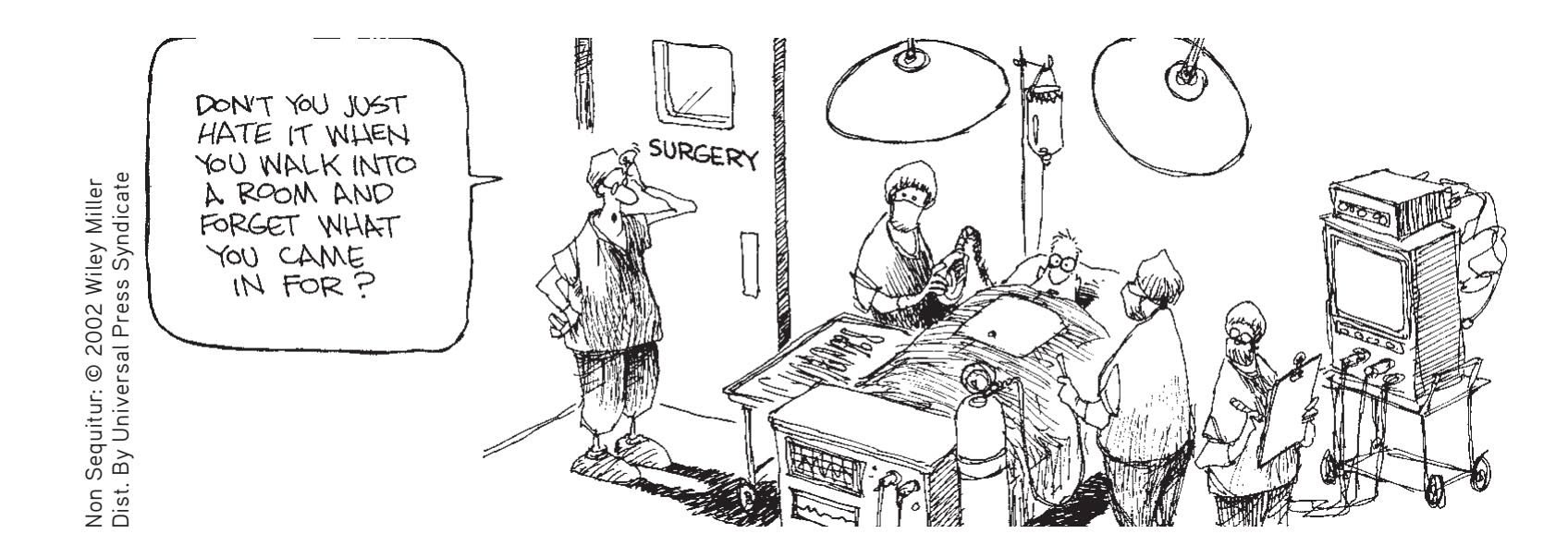

**YOU DON'T NEED TO BE A PSYCHOL-OGIST** to notice that the classroom atmosphere can be a little tense the day after the first exam. As we handed back the test results, several faces fell. Many of the students were freshmen and not yet accustomed to the selfpaced learning required in a college course. But there were also several older adults, including two military vets, one recently returned from Afghanistan.

"So let's go over these test questions," your author Sandy began. "I noticed a lot of you had trouble with the difference between independent and dependent variables. Maybe we should talk about that again before we go on to Chapter 2."

Jacob frowned. "I can't understand why I did so badly," he said. "I mean, I read the chapter! Look." He held up his textbook. The pages were heavily underlined and covered with highlight colors—yellow, blue, and green.

It isn't unusual for students to have trouble with their first real exam in college. Knowing that, we usually take some time to talk about study skills after exams are returned. "How did you prepare for the exam?" your author Susan asked the class.

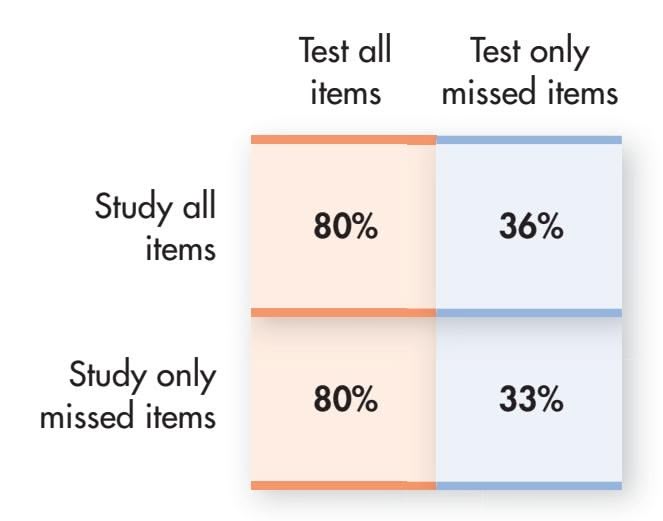

"I made flashcards," Latisha said. "But it didn't seem to help that much. I only got a B-, and I thought I really knew this stuff."

"Flashcards can be a great technique," Sandy said, "if you use them correctly."

Latisha looked puzzled. "What do you mean? I used them the way everybody uses flashcards. I tested myself and if I knew the answer, I set the card aside. I kept running through the ones I missed until they were all gone and I knew them all."

"Well, believe it or not," Sandy said, "psychologists have done a lot of research on learning new material, and it turns out that that's *not* the most effective way to use flashcards."

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 2 11/20/15 11:58 AM

"Stay tuned," Sandy said with a smile. "We're going to talk about it in today's class."

Jenna broke in. "I always freeze on tests. They stress me out so bad my mind goes blank."

"I do too," Tyler piped up. "So my girlfriend gave me this bracelet to wear for exams. She swears by hers. Do you think it helps?"

"What is that?" Sandy said. Tyler handed the heavy metal bracelet to Sandy. "What's it supposed to do?"

"It's made of some kind of special metal—maybe titanium?" Tyler said. "It's magnetic. Oh, and the Web site said it generated a negative ion field, It didn't make a whole lot of sense to me. But my girlfriend said that a lot of famous baseball players and golfers wear one. It's supposed to help with pain but it's also supposed to help you concentrate and give you a better memory. I figured it couldn't hurt, so why not try it?"

"I'm not aware of any research on using magnets for concentration or memory," Sandy said carefully. "But we can certainly look it up and let you know what we find out."

Later in the chapter, we'll share what we found out about magnetic jewelry—and more important, what psychologists have discovered about

- ❯ **IntroductIon:** What Is Psychology?

- ❯ Contemporary Psychology

- ❯ The Scientific Method

- ❯ Descriptive Research

- ❯ Experimental Research

- ❯ Ethics in Psychological Research

- ❯ Closing Thoughts

- ❯ **PSYcH For Your LIFE:** Successful Study Techniques

1

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 1 11/20/15 11:58 AM

2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

the most effective ways to study. You'll also see how psychological research can help you critically evaluate new ideas and claims that you encounter outside the classroom.

As you'll discover, psychology has a lot to say about many of the questions that are of interest to college students. In this introductory chapter, we'll explore the scope of contemporary psychology as well as psychology's historical origins. The common theme connecting psychology's varied topics is its reliance on a solid foundation of scientific evidence. By the end of the chapter, you'll have a better appreciation of the scientific methods that psychologists use to answer questions, big and small, about behavior and mental processes.

Welcome to psychology!

# **[INTRODUCTION:](#page--1-0)** What Is Psychology?

### KEY THEME

Today, psychology is defined as the science of behavior and mental processes, a definition that reflects psychology's origins and history.

#### KEY QUESTIONS

- ❯ What are the goals and scope of contemporary psychology?

- ❯ What roles did Wundt and James play in establishing psychology?

- ❯ What were the early schools of thought and approaches in psychology, and how did their views differ?

**Psychology** is formally defined as *the scientific study of behavior and mental processes.* But this definition is deceptively simple. As you'll see in this chapter, the scope of contemporary psychology is very broad—ranging from the behavior of a single brain cell to the behavior of a crowd of people or even entire cultures.

Many people think that psychologists are primarily—or even exclusively interested in studying and treating psychological disorders and problems. But as this chapter will show, psychologists are just as interested in "normal," everyday behaviors and mental processes—topics like learning and memory, emotions and motivation, relationships and loneliness. And, psychologists seek ways to use the knowledge that they discover through scientific research to optimize human performance and potential in many different fields, from classrooms to offices to the military.

**psychology** The scientific study of behavior and mental processes.

**MYTH** SCIENCE

Is it true that the field of psychology focuses primarily on treating people with psychological problems and disorders?

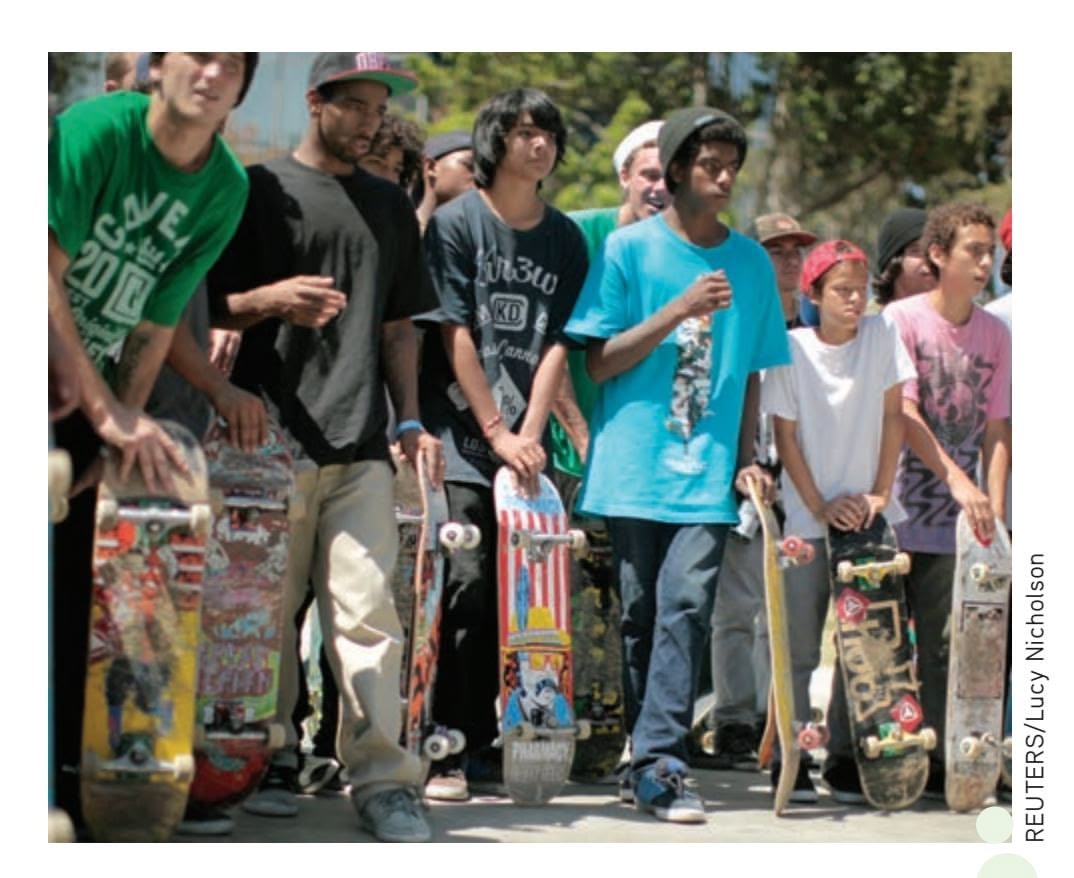

**What Do Psychologists Study?** It's International Pillow Fight Day and these young members of a flash mob join the fun in Vancouver, British Columbia. What motivated them to show up? What kind of emotions might they be feeling? How does the presence of like-minded others affect their behavior? Whether studying the behavior of a crowd of people or a single brain cell, psychologists rely on the scientific method to guide their investigations.

Carmine M.

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 2 11/20/15 11:58 AM

**INTRODUCTION:** What Is Psychology? 3

The four basic goals of psychology are to *describe, predict, explain,* and *control* or *influence* behavior and mental processes. To illustrate how these goals guide psychological research, think about our classroom discussion. Most people, like Jenna in the Prologue, have an intuitive understanding of what the word *stress* refers to. Psychologists, however, seek to go beyond intuitive or "common sense" understandings of human experience.

Here's how psychology's goals might help guide research on stress:

- **1.***Describe:* Trying to objectively *describe* the experience of stress, Dr. Garcia studies the sequence of emotional responses that occur during stressful experiences.

- **2.***Predict:* Dr. Kiecolt investigates responses to different kinds of challenging events, hoping to be able to *predict* the kinds of events that are most likely to evoke a stress response.

- **3.***Explain:* Seeking to *explain* why some people are more vulnerable to the effects of stress than others, Dr. Lazarus studies the different ways in which people respond to natural disasters.

- **4.***Control or Influence:* After studying the effectiveness of different coping strategies, Dr. Folkman helps people use those coping strategies to better *control* their reactions to stressful events.

How did psychology evolve into today's diverse and rich science? We begin this introductory chapter by stepping backward in time to describe the early origins of psychology and its historical development. As you become familiar with how psychology began and developed, you'll have a better appreciation for how it has come to encompass such diverse subjects. Indeed, the early history of psychology is the history of a field struggling to define itself as a separate and unique scientific discipline. The early psychologists debated such fundamental issues as:

- • What is the proper subject matter of psychology?

- • What methods should be used to investigate psychological issues?

- • Should psychological findings be used to change or enhance human behavior?

These debates helped set the tone of the new science, define its scope, and set its limits. Over the past century, the shifting focus of these debates has influenced the [topics studied and the research methods used.](#page--1-0)

## Psychology's Origins THE INFLUENCE OF PHILOSOPHY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The earliest origins of psychology can be traced back several centuries to the writings of the great philosophers. More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote extensively about topics such as sleep, dreams, the senses, and memory. Many of Aristotle's ideas remained influential until the beginnings of modern science in the seventeenth century (Kheriaty, 2007).

At that time, the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) proposed a doctrine called *interactive dualism*—the idea that mind and body were separate entities that interact to produce sensations, emotions, and other conscious experiences. Today, psychologists continue to explore the relationship between mental activity and the brain.

Philosophers also laid the groundwork for another issue that would become central to psychology, the *nature–nurture issue.* For centuries, philosophers debated which was more important: the inborn *nature* of the individual or the environmental influences that *nurture* the individual. This debate was sometimes framed as nature *versus* nurture. Today, however, psychologists understand that "nature" and "nuture" are impossible to completely disentangle (Sameroff, 2010). So, while some psychologists do investigate the relative influences of *heredity versus environmental factors* on behavior, today's researchers also focus on studying the dynamic *interaction* between environmental factors and genetic heritage (Dick & others, 2015; Szyf, 2013).

**Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.)** The first Western thinker to study psychological topics, Aristotle combined the logic of philosophy with empirical observation. His best-known psychological work, *De Anima*, is regarded as the first systematic treatise on psychology. Its topics included such basic psychological processes as the senses, perception, memory, thinking, and motivation. Aristotle's writings on psychology anticipated topics and theories that would be central to scientific psychology centuries later.

**Nature or Nurture?** Both father and daughter are clearly enjoying the experience of making art together. Is the child's interest in art an expression of her natural tendencies, or is it the result of her father's encouragement and teaching? Originally debated by philosophers hundreds of years ago, the relationship between heredity and environmental factors continues to interest psychologists today (Dick & others, 2015).

David Sacks/Getty Images

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 3 11/20/15 11:58 AM

4 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

**structuralism** Early school of psychology that emphasized studying the most basic components, or structures, of conscious experiences.

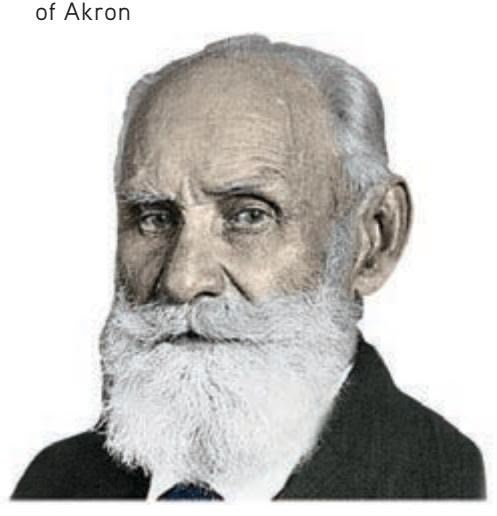

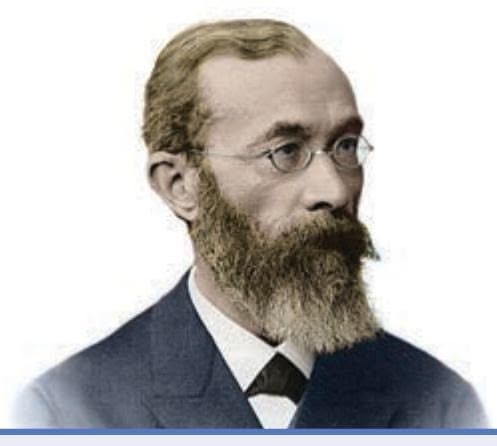

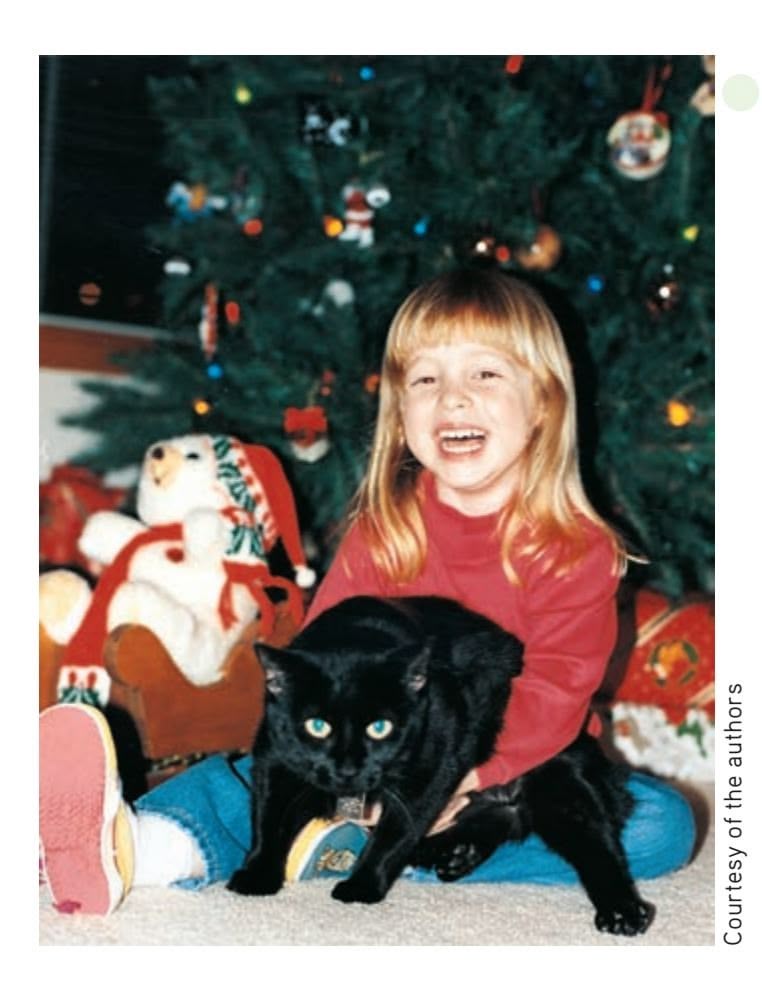

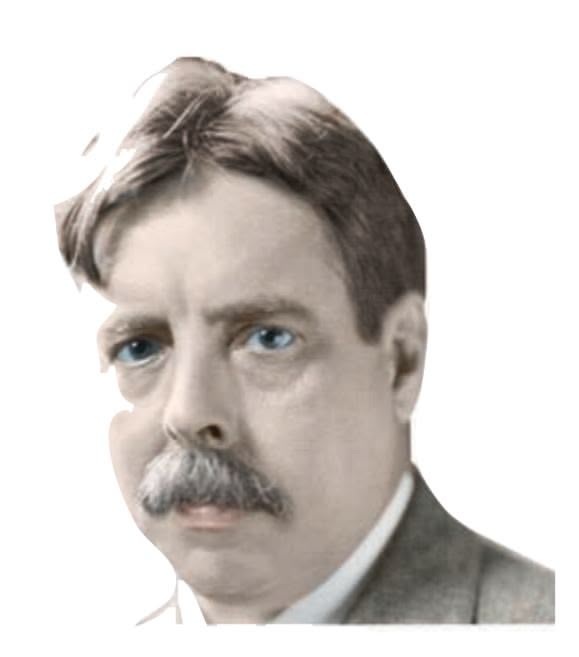

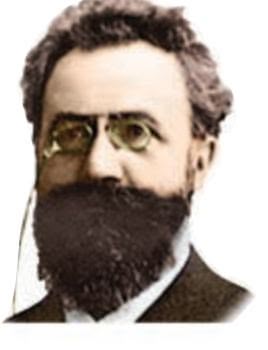

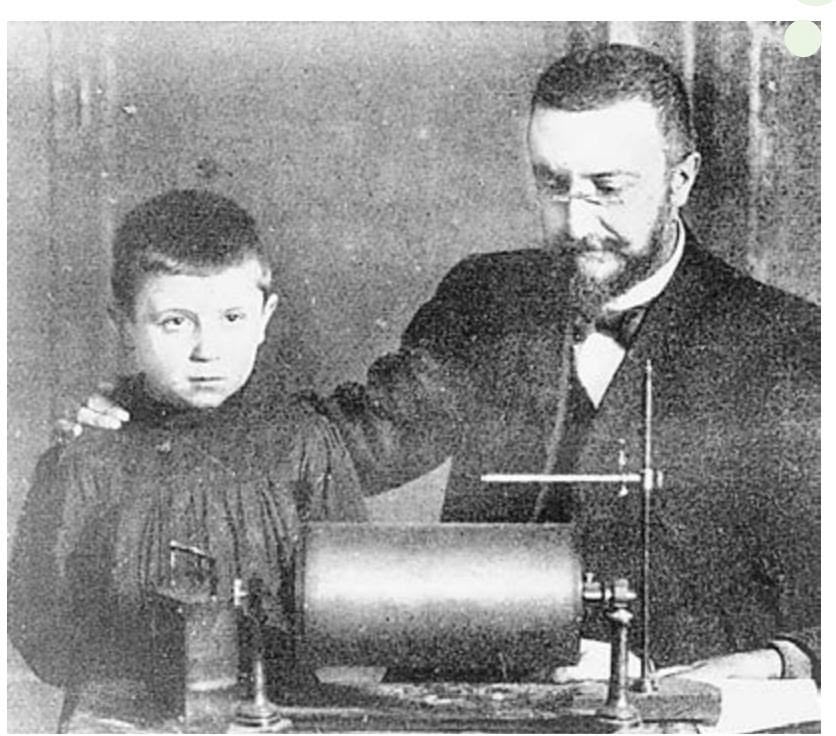

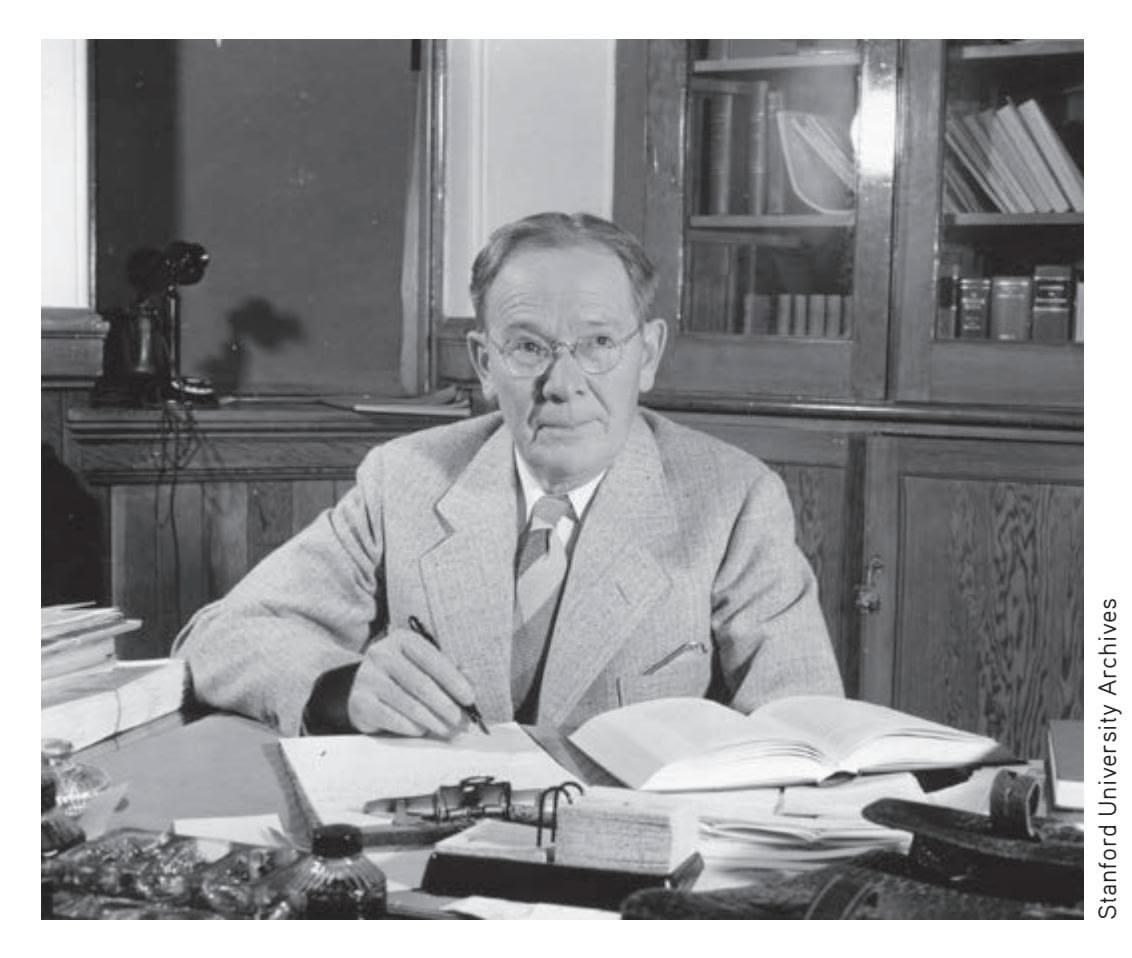

**Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920)** German physiologist Wilhelm Wundt is generally credited as being the founder of psychology as an experimental science. In 1879, he established the first psychology research laboratory. By the early 1900s, Wundt's research had expanded to include such topics as cultural psychology and developmental psychology (Wong, 2009).

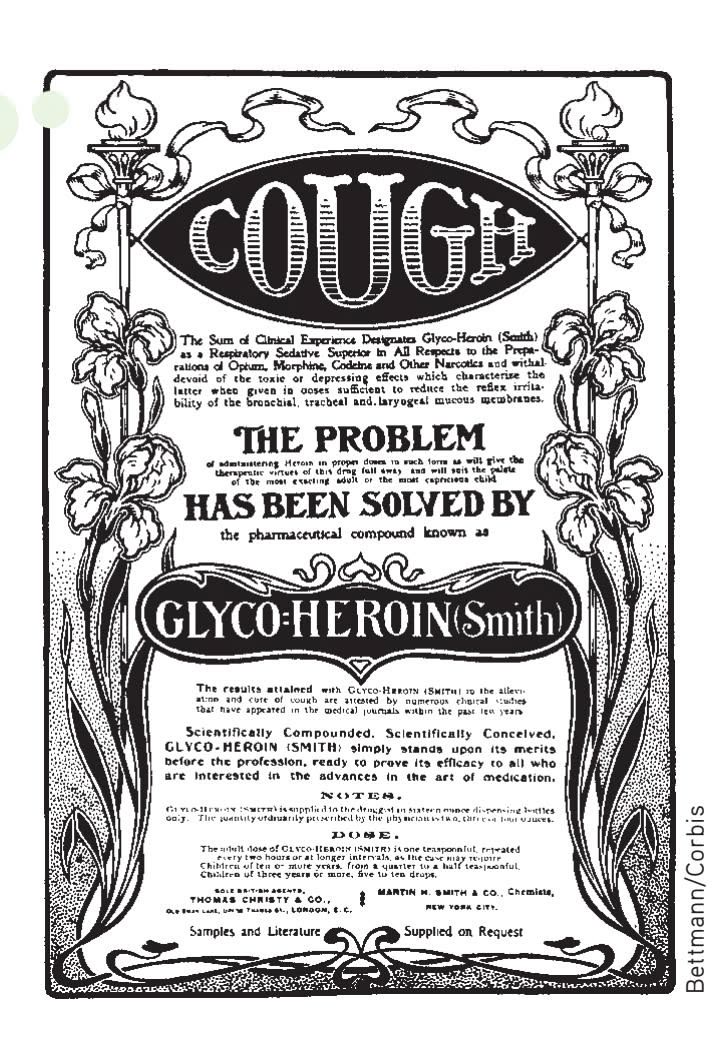

Bettmann/Corbis

**Edward B. Titchener (1867–1927)** In contrast to the psychology programs at both Harvard and Columbia at the time, Edward Titchener welcomed women into his graduate program at Cornell. In fact, more women completed their psychology doctorates under Titchener's direction than under any other male psychologist of his generation (Evans, 1991).

Archives of the History of American Psychology, The University of Akron. Color added by publisher

Such philosophical discussions influenced the topics that would be considered in psychology. But the early philosophers could advance the understanding of human behavior only to a certain point. Their methods were limited to intuition, observation, and logic.

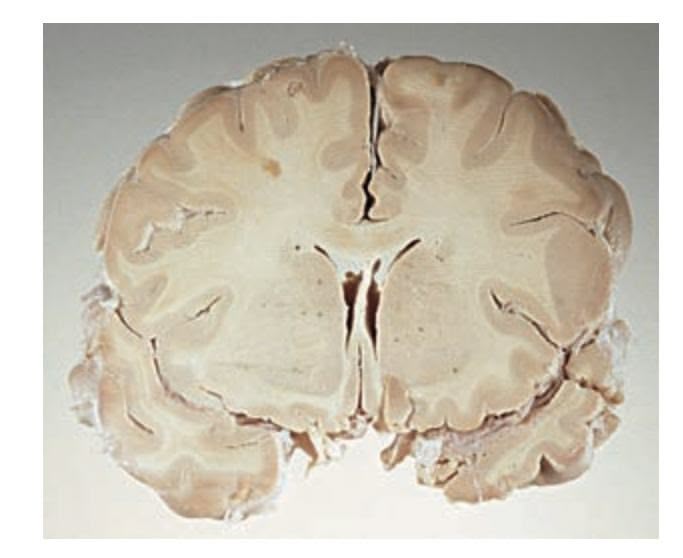

The eventual emergence of psychology as a science hinged on advances in other sciences, particularly physiology. *Physiology* is a branch of biology that studies the functions and parts of living organisms, including humans. In the 1600s, physiologists were becoming interested in the human brain and its relation to behavior. By the early 1700s, it was discovered that damage to one side of the brain produced a loss of function in the opposite side of the body. By the early 1800s, the idea that different brain areas were related to different behavioral functions was being vigorously debated. Collectively, the early scientific discoveries made by physiologists were establishing the foundation for an idea that was to prove critical to the emergence of psychology—namely, that scientific methods could be applied to answering questions [about behavior and mental proce](#page--1-0)sses.

## Wilhelm Wundt THE FOUNDER OF PSYCHOLOGY

By the second half of the 1800s, the stage had been set for the emergence of psychology as a distinct scientific discipline. The leading proponent of this idea was a German physiologist named **Wilhelm Wundt** (Gentile & Miller, 2009). Wundt used scientific methods to study fundamental psychological processes, such as mental reaction times in response to visual or auditory stimuli. For example, Wundt tried to measure precisely how long it took a person to consciously detect the sight and sound of a bell being struck.

A major turning point in psychology occurred in 1874, when Wundt outlined the connections between physiology and psychology in his landmark text, *Principles of Physiological Psychology* (Diamond, 2001). He also promoted his belief that psychology should be established as a separate scientific discipline that would use experimental methods to study mental processes. In 1879, Wundt realized that goal when he opened the first psychology research laboratory at the University of Leipzig. Many mark this event as the formal beginning of psychology as an experimental science (Kohls & Benedikter, 2010).

Wundt defined psychology as the study of consciousness and emphasized the use of experimental methods to study and measure it. Until he died in 1920, Wundt exerted a strong influence on the development of psychology as a science (Wong, 2009). Two hundred students from around the world traveled to Leipzig to earn doctorates in experimental psychology under Wundt's direction. Over the years, some 17,000 students attended Wundt's afternoon lectures on general psychology, which often [included demonstrations of dev](#page--1-0)ices he had developed to measure mental processes (Blumenthal, 1998).

## Edward B. Titchener STRUCTURALISM

One of Wundt's most devoted students was a young Englishman named **Edward B. Titchener.** After earning his doctorate in Wundt's laboratory, Titchener began teaching at Cornell University in New York. There he established a psychology laboratory that ultimately spanned 26 rooms.

Titchener shared many of Wundt's ideas about the nature of psychology. Eventually, however, Titchener developed his own approach, which he called *structuralism.* **Structuralism** became the first major school of thought in psychology. Structuralism held that even our most complex conscious experiences could be broken down into elemental *structures,* or component parts, of sensations and feelings. To identify these structures of conscious thought, Titchener trained subjects in a procedure

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 4 11/20/15 11:58 AM

**INTRODUCTION:** What Is Psychology? 5

called *introspection.* The subjects would view a simple stimulus, such as a book, and then try to reconstruct their sensations and feelings immediately after viewing it. (In psychology, a *stimulus* is anything perceptible to the senses, such as a sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste.) They might first report on the colors they saw, then the smells, and so on, in the attempt to create a total description of their conscious experience (Titchener, 1896).

In addition to being distinguished as the first school of thought in early psychology, Titchener's structuralism holds the dubious distinction of being the first school to disappear. Titchener's death in 1927 essentially marked the end of structuralism as an influential school of thought in psychology. But even before Titchener's death, structuralism was often criticized for relying too heavily on the method of introspection.

As noted by Wundt and other scientists, introspection had significant limitations. First, introspection was an unreliable method of investigation. Different subjects often provided very different introspective reports about the same stimulus. Even subjects well trained in introspection varied in their responses to the same stimulus from trial to trial.

Second, introspection could not be used to study children or animals. Third, complex topics, such as learning, development, mental disorders, and personality, could not be investigated using introspection. Ultimately, the methods and goals of struc[turalism were simply too limit](#page--1-0)ed to accommodate the rapidly expanding interests of the field of psychology.

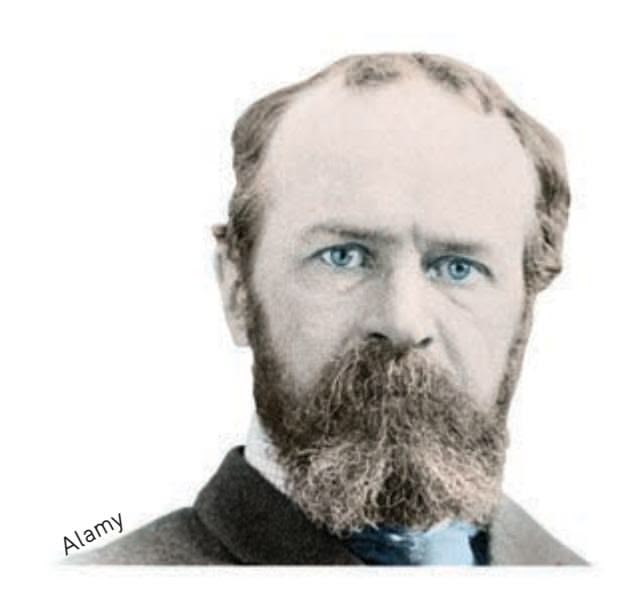

## William James FUNCTIONALISM

By the time Titchener arrived at Cornell University, psychology was already well established in the United States. The main proponent of American psychology was one of Harvard's most outstanding teachers—**William James.** James had become intrigued by the emerging science of psychology after reading one of Wundt's articles. But there were other influences on the development of James's thinking.

Like many other scientists and philosophers of his generation, James was fascinated by the idea that different species had evolved over time (Menand, 2001). Many nineteenth-century scientists in England, France, and the United States were *evolutionists*—that is, they believed that species had not been created all at once but rather had changed over time (Caton, 2007).

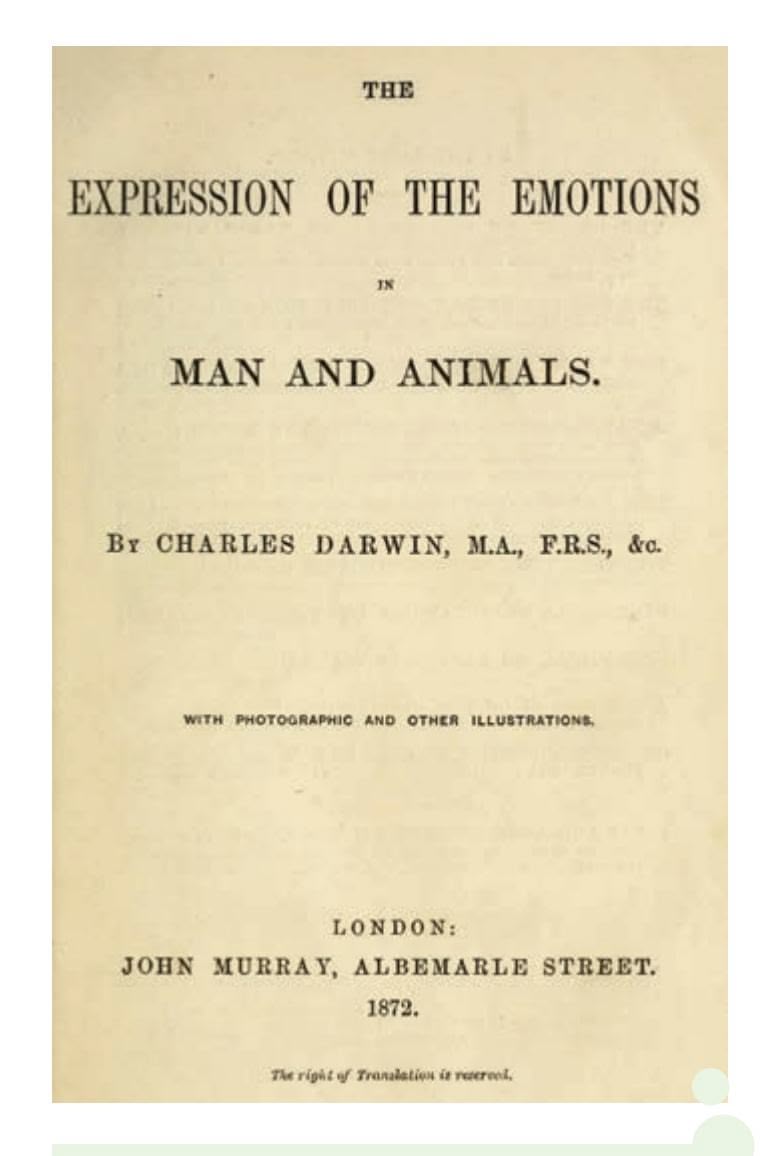

In the 1850s, British philosopher Herbert Spencer had published several works arguing that modern species, including humans, were the result of gradual evolutionary change. In 1859, **Charles Darwin's** groundbreaking work, *On the Origin of Species,* was published. James and his fellow thinkers actively debated the notion of evolution, which came to have a profound influence on James's

importance of adaptation to environmental challenges. In the early 1870s, James began teaching a physiology and anatomy class at Harvard University. An intense, enthusiastic teacher, James was prone to changing the subject matter of his classes as his own interests changed (B. Ross, 1991). By the late 1870s, James was teaching classes devoted exclusively to the topic of psychology.

ideas (Richardson, 2006). Like Darwin, James stressed the

At about the same time, James began writing a comprehensive textbook of psychology, a task that would take him more than a decade. James's *Principles of Psychology* was finally published in 1890. Despite its length of more than 1,400 pages, *Principles of Psychology* quickly became the leading psychology textbook.

**William James (1842–1910)** Harvard professor William James was instrumental in establishing psychology in the United States. In 1890, James published a highly influential text, *Principles of Psychology.* James's ideas became the basis of another early school of psychology, called *functionalism,* which stressed studying the adaptive and practical functions of human behavior.

Bettmann/Corbis

**Charles Darwin (1809–1882)** Naturalist Charles Darwin had a profound influence on the early development of psychology. Darwin was not the first scientist to propose that complex organisms evolved from simpler species (Caton, 2007). However, Darwin's book, *On the Origin of Species,* published in 1859, gathered evidence from many different scientific fields to present a compelling account of evolution through the mechanism of natural selection. Darwin's ideas have had a lasting impact on scientific thought (Dickins, 2011; Pagel, 2009).

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 5 11/20/15 11:58 AM

6 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

**functionalism** Early school of psychology that emphasized studying the purpose, or function, of behavior and mental experiences.

**G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924)** G. Stanley Hall helped organize psychology in the United States. Among his many achievements was the establishment of the first psychology research laboratory in the United States. Hall also founded the American Psychological Association.

Corbis

**Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930)** Under the direction of William James, Mary Whiton Calkins completed all the requirements for a Ph.D. in psychology. Calkins had a distinguished professional career. She established a psychology laboratory at Wellesley College and became the first woman president of the American Psychological Association.

In it, James discussed such diverse topics as brain function, habit, memory, sensation, perception, and emotion.

James's ideas became the basis for a new school of psychology, called functionalism. **Functionalism** stressed the importance of how behavior *functions* to allow people and animals to adapt to their environments. Unlike structuralists, functionalists did not limit their methods to introspection. They expanded the scope of psychological research to include direct observation of living creatures in natural settings. They also examined how psychology could be applied to areas like education, child rearing, and the work environment.

Both the structuralists and the functionalists thought that psychology should focus on the study of conscious experiences. But the functionalists had very different ideas about the nature of consciousness and how it should be studied. Rather than trying to identify the essential structures of consciousness at a given moment, James saw consciousness as an ongoing stream of mental activity that shifts and changes.

Like structuralism, functionalism no longer exists as a distinct school of thought in contemporary psychology. Nevertheless, functionalism's twin themes of the importance of the adaptive role of behavior and the application of psychology to enhance human behavior are still important in modern psychology.

## WILLIAM JAMES AND HIS STUDENTS

Like Wundt, James profoundly influenced psychology through his students, many of whom became prominent American psychologists. Two of James's most notable students were G. Stanley Hall and Mary Whiton Calkins.

In 1878, **G. Stanley Hall** received the first Ph.D. in psychology awarded in the United States. Hall founded the first psychology research laboratory in the United States at Johns Hopkins University in 1883. He also began publishing the *American Journal of Psychology,* the first U.S. journal devoted to psychology. Most important, in 1892, Hall founded the American Psychological Association and was elected its first president (Anderson, 2012). Today, the American Psychological Association (APA) is the world's largest professional organization of psychologists, with approximately 150,000 members. (The Association for Psychological Science, founded in 1988, has about 26,000 members.)

In 1890, **Mary Whiton Calkins** was assigned the task of teaching experimental psychology at a new women's college—Wellesley College. Calkins studied with James at nearby Harvard University. She completed all the requirements for a Ph.D. in psychology. However, Harvard refused to grant her the Ph.D. degree because she was a woman and at the time Harvard was not a coeducational institution (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010).

Although never awarded the degree she had earned, Calkins made several notable contributions to psychology. She conducted research in dreams, memory, and personality. In 1891, she established a psychology laboratory at Wellesley College. At the turn of the twentieth century, she wrote a well-received textbook, titled *Introduction to Psychology.* In 1905, Calkins was elected president of the American Psychological Association—the first woman, but not the last, to hold that position.

For the record, the first American woman to earn an official Ph.D. in psychology was **Margaret Floy Washburn,** Edward Titchener's first doctoral student at Cornell University. Washburn strongly advocated the scientific study of the mental processes of different animal species. In 1908, she published an influential text, titled *The Animal Mind.* Her book summarized research on sensation, perception, learning, and other "inner experiences" of different animal species. In 1921, Washburn became the second woman elected president of the American Psychological Association (Viney & Burlingame-Lee, 2003).

Finally, one of G. Stanley Hall's notable students was **Francis C. Sumner.** Sumner was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. in psychology, awarded by Clark University in 1920. After teaching at several southern universities,

**INTRODUCTION:** What Is Psychology? 7

**Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939)** After becoming the first American woman to earn an official Ph.D. in psychology, Washburn went on to a distinguished career. Despite the discrimination against women that was widespread in higher education during the early twentieth century, Washburn made many contributions to psychology. She was the second woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association.

Archives of the History of American Psychology, The University of Akron. Color added by publisher

**Francis C. Sumner (1895–1954)** Francis Sumner studied under G. Stanley Hall at Clark University. In 1920, he became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in psychology. Sumner later joined Howard University in Washington, D.C., and helped create a strong psychology program that led the country in training African American psychologists (Belgrave & Allison, 2010).

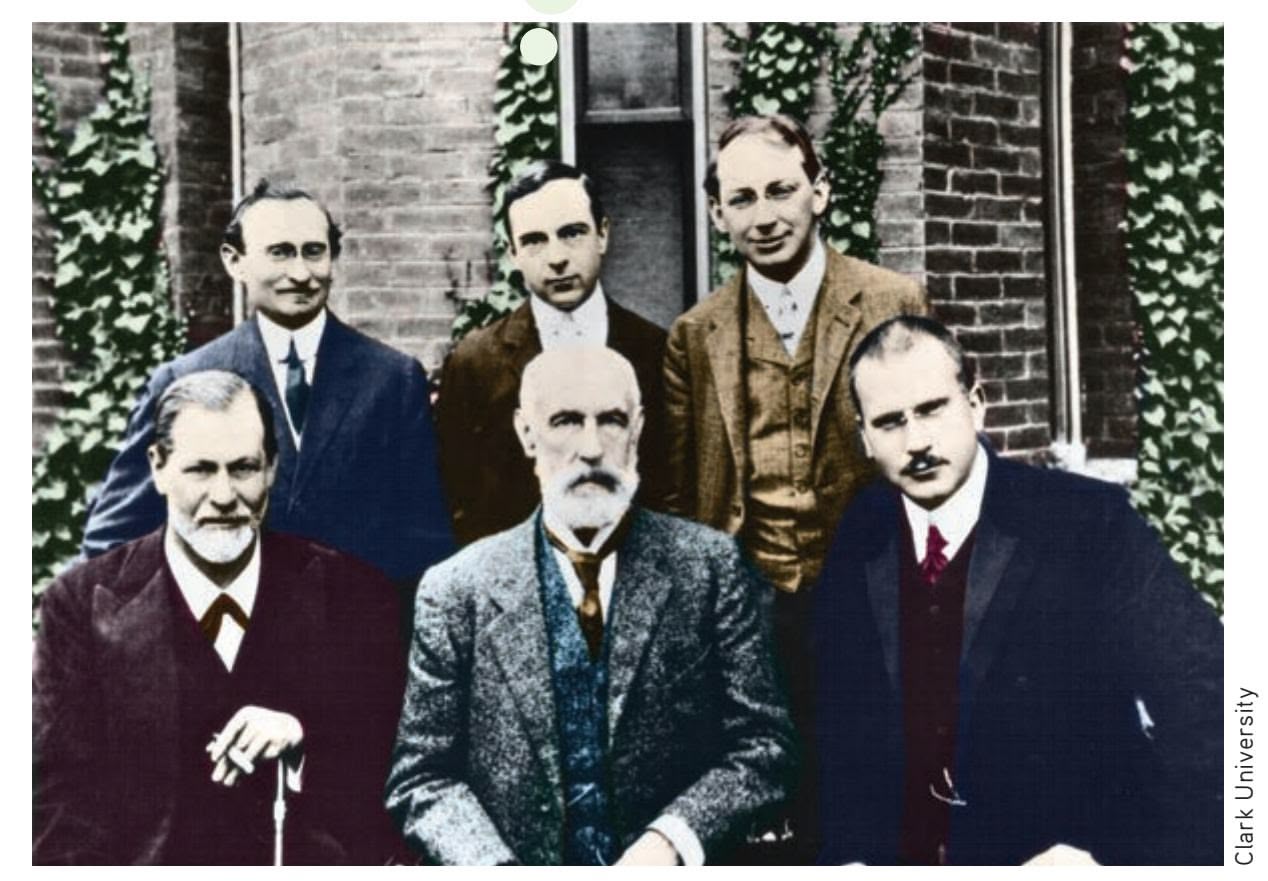

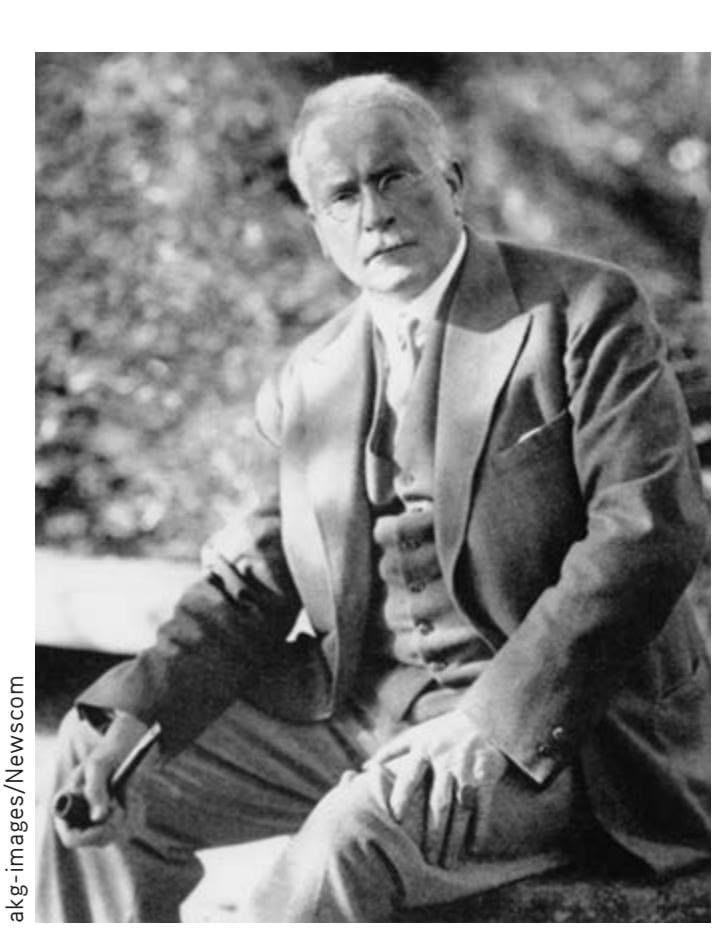

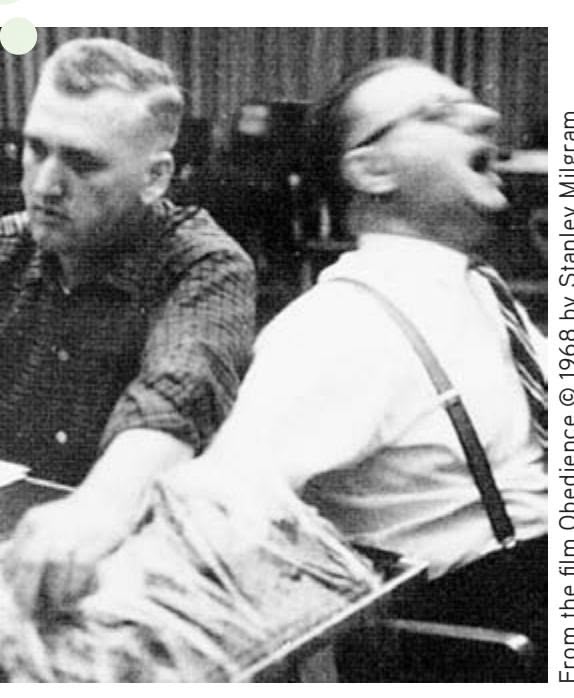

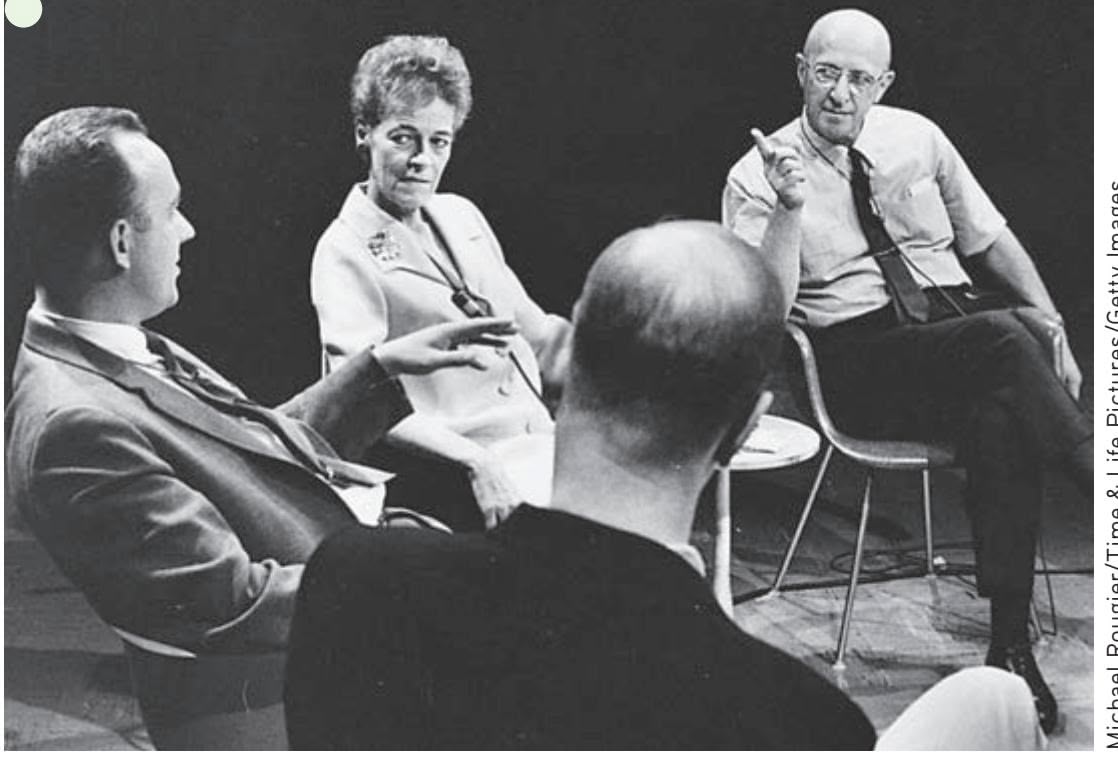

**Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)** In 1909, Freud *(front left)* and several other psychoanalysts were invited by G. Stanley Hall *(front center)* to participate in Clark University's twentieth-anniversary celebration in Worcester, Massachusetts (Hogan, 2003). Freud delivered five lectures on psychoanalysis. Listening in the audience was William James, who later wrote to a friend that Freud struck him as "a man obsessed with fixed ideas" (Rosenzweig, 1997). Carl Jung *(front right),* who later developed his own theory of personality, also attended this historic conference.

Sumner moved to Howard University in Washington, D.C. While at Howard, he published papers on a wide variety of topics and chaired a psychology department that produced more African American psychologists than all other American colleges and universities combined (Guthrie, 2000, 2004). One of Sumner's most famous students was **Kenneth Bancroft Clark.** Clark's research on the negative effects of discrimination was instrumental in the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision to end segregation in schools (Jackson, 2006). In 1970, Clark became the first African American president of [the American Psycho](#page--1-0)logical Association (Belgrave & Allison, 2010).

## Sigmund Freud PSYCHOANALYSIS

Wundt, James, and other early psychologists emphasized the study of conscious experiences. But at the turn of the twentieth century, new approaches challenged the principles of both structuralism and functionalism.

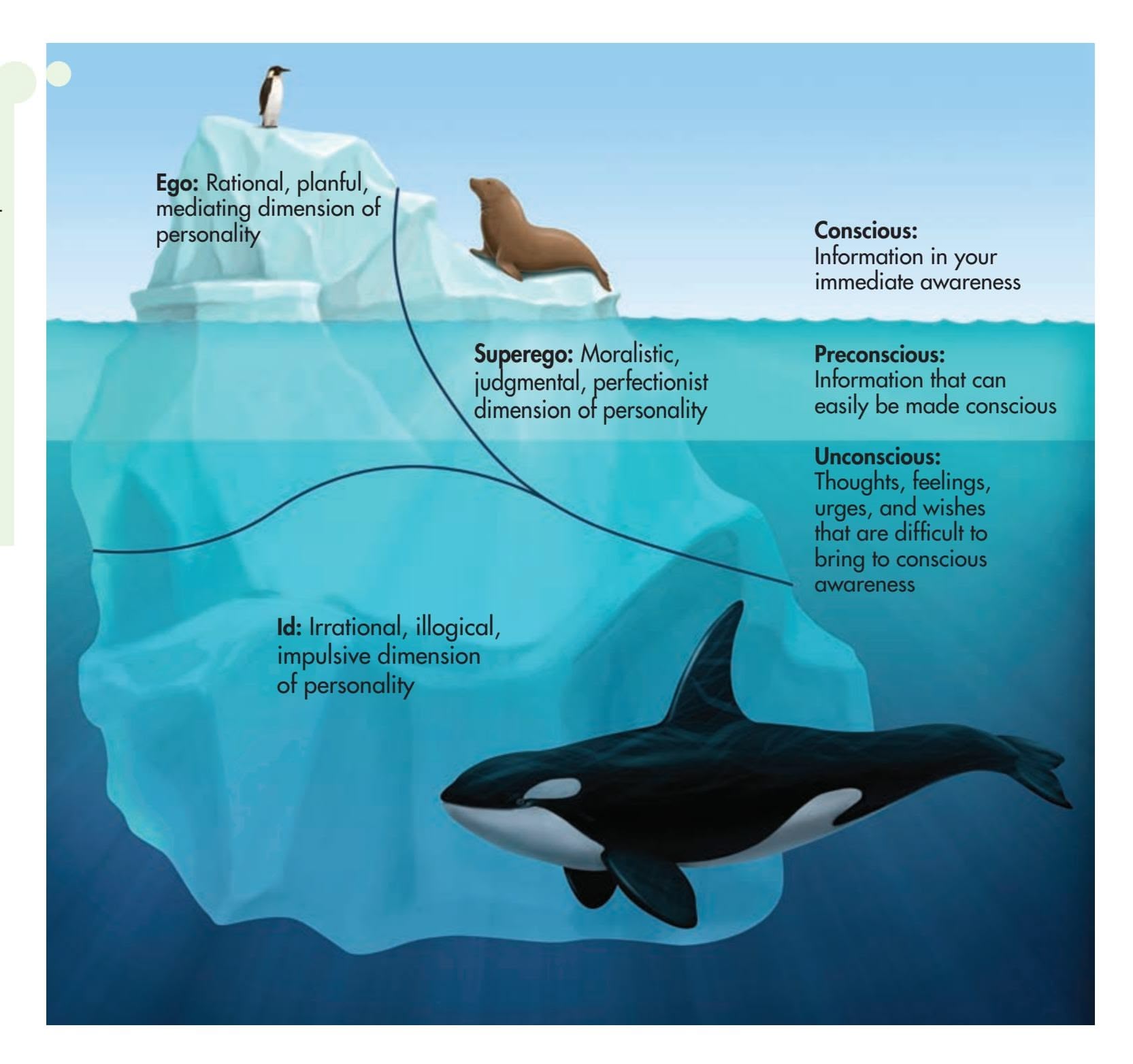

In Vienna, Austria, a physician named **Sigmund Freud** was developing an intriguing theory of personality based on uncovering causes of behavior that were *unconscious,* or hidden from the person's conscious awareness. Freud's school of thought, called **psychoanalysis,** emphasized the role of unconscious conflicts in determining behavior and personality. Freud himself was a neurologist, *not* a psychologist. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis had a strong influence on psychological thinking in the early part of the century.

Freud's psychoanalytic theory of personality and behavior was based largely on his work with his patients and on insights derived from self-analysis. Freud believed that

**MYTH** SCIENCE Is it true that Sigmund Freud was the first psychologist?

**psychoanalysis** Personality theory and form of psychotherapy that emphasizes the role of unconscious factors in personality and behavior.

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 7 11/20/15 11:58 AM

8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

**behaviorism** School of psychology and theoretical viewpoint that emphasizes the study of observable behaviors, especially as they pertain to the process of learning.

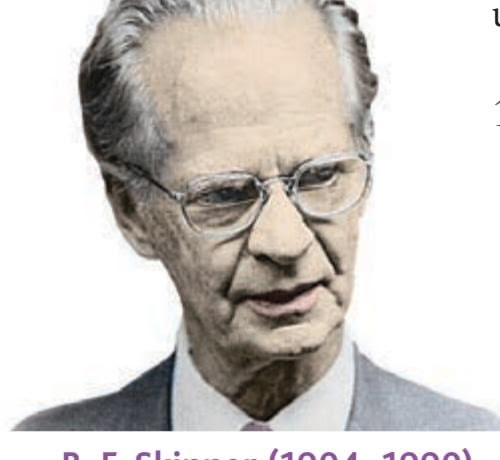

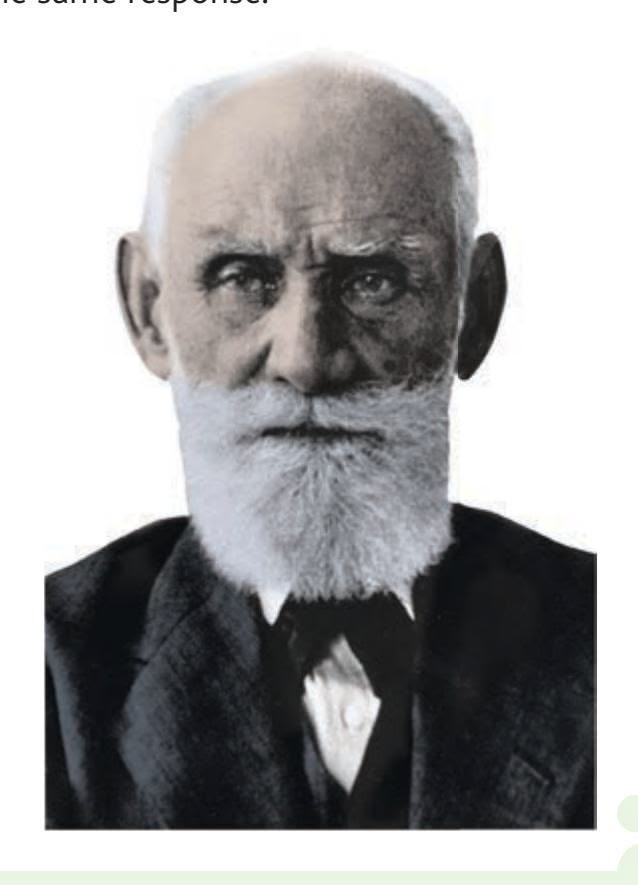

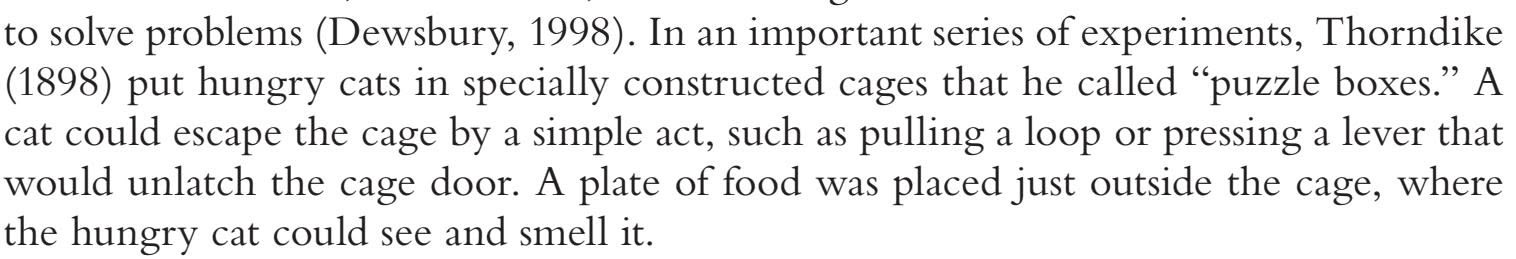

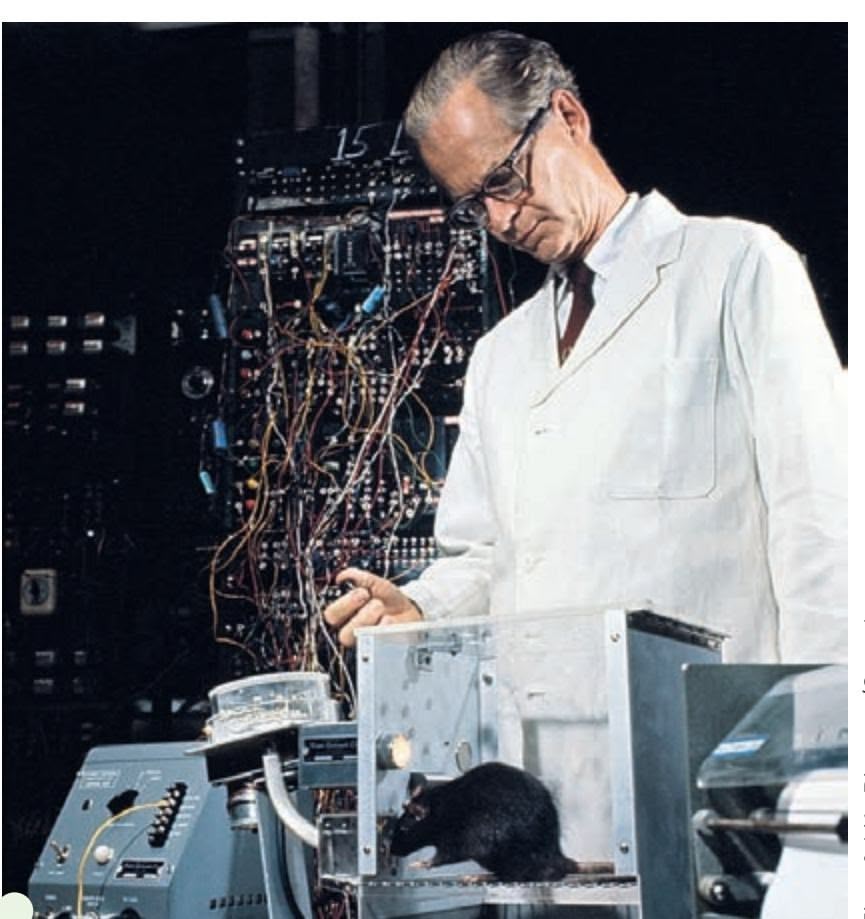

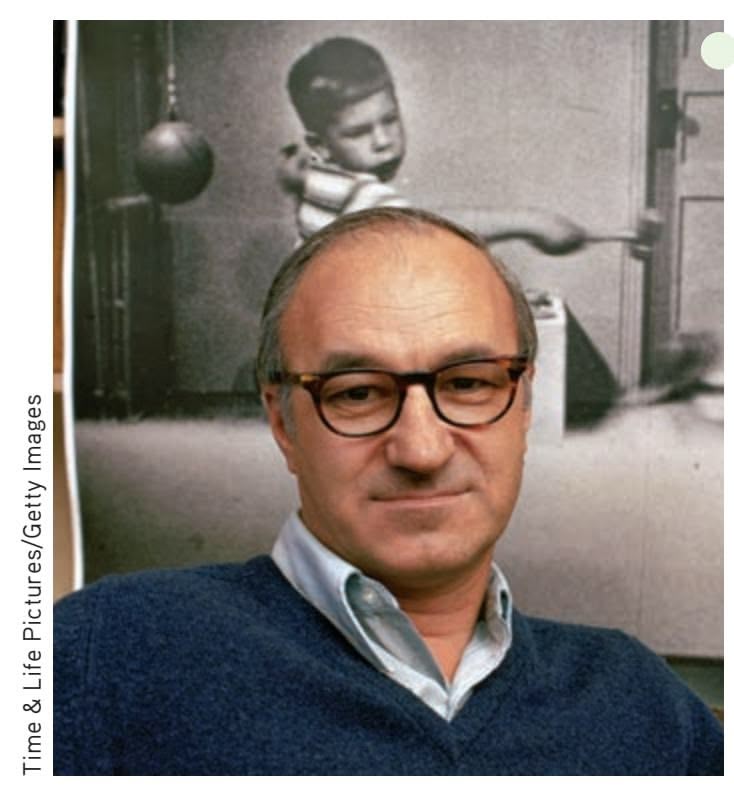

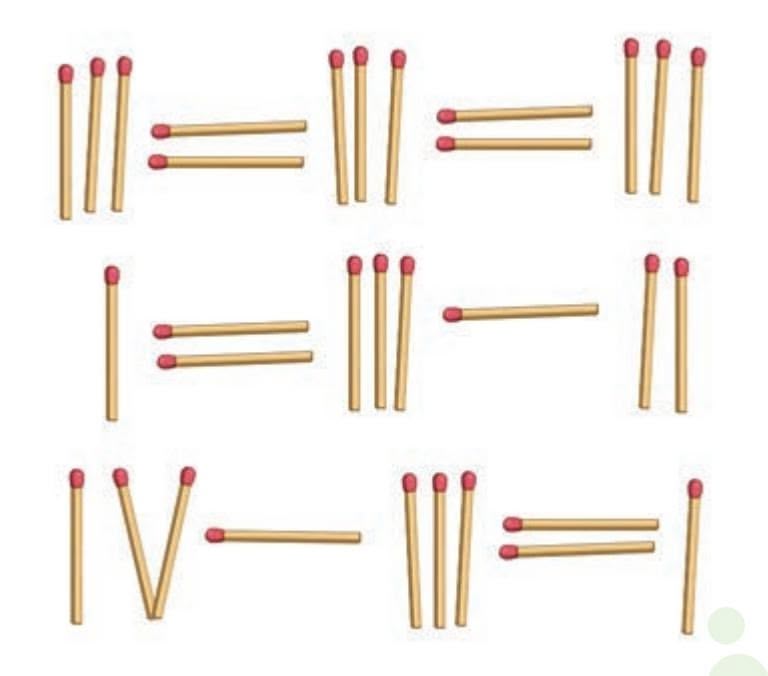

**Three Key Scientists in the Development of Behaviorism** Building on the pioneering research of Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, American psychologist John B. Watson founded the school of behaviorism. Behaviorism advocated that psychology should study observable behaviors, not mental processes. Following Watson, B. F. Skinner continued to champion the ideas of behaviorism. Skinner became one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century. Like Watson, he strongly advocated the study of observable behaviors rather than mental processes.

(t) Culver Pictures/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY (bl) Underwood & Underwood/ Corbis (br) Archives of the History of American Psychology, The University

**Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936)**

**John B. Watson (1878–1958)**

human behavior was motivated by unconscious conflicts that were almost always sexual or aggressive in nature. Past experiences, especially childhood experiences, were thought to be critical in the formation of adult personality and behavior. According to Freud (1904), glimpses of these unconscious impulses are revealed in everyday life in dreams, memory blocks, slips of the tongue, and spontaneous humor. Freud believed that when unconscious conflicts became extreme, psychological disorders could result.

Freud's psychoanalytic theory of personality also provided the basis for a distinct form of psychotherapy. Many of the fundamental ideas of psychoanalysis, such as the importance of unconscious influences and early childhood experiences, continue to influence psychologists and other professionals in the mental health field. We'll [explore Freud's theory in more](#page--1-0) depth in Chapter 10 on personality and Chapter 14 on therapies.

## John B. Watson BEHAVIORISM

The course of psychology changed dramatically in the early 1900s when another approach, called **behaviorism,** emerged as a dominating force. Behaviorism rejected the emphasis on consciousness promoted by structuralism and functionalism. It also flatly rejected Freudian notions about unconscious influences, claiming that such ideas were unscientific and impossible to test. Instead, behaviorism contended that psychology should focus its scientific investigations strictly on *overt behavior*—observable behaviors that could be objectively measured and verified.

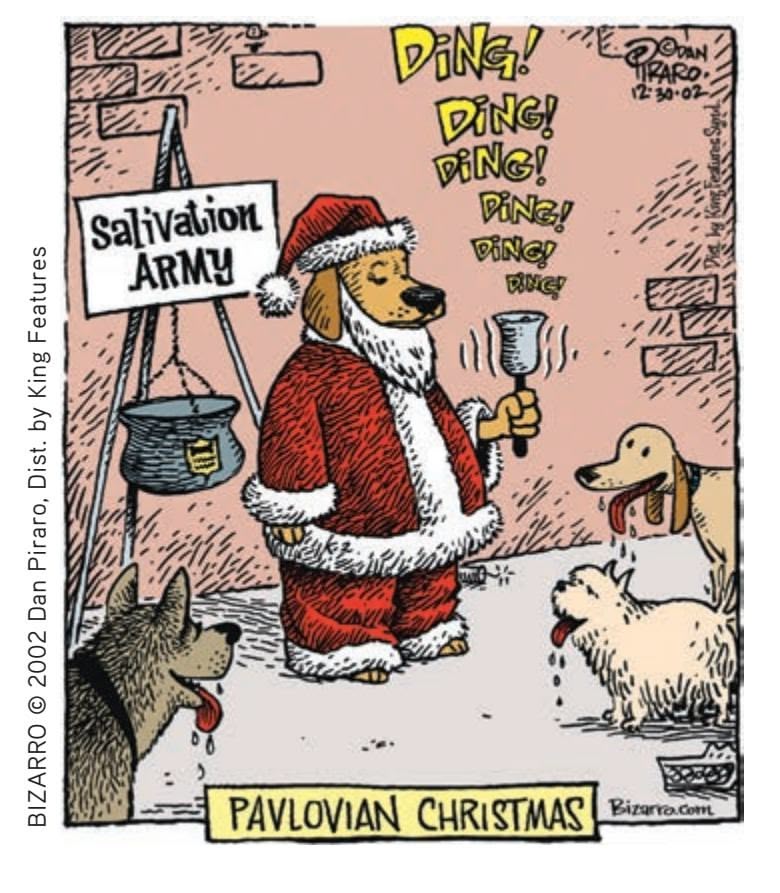

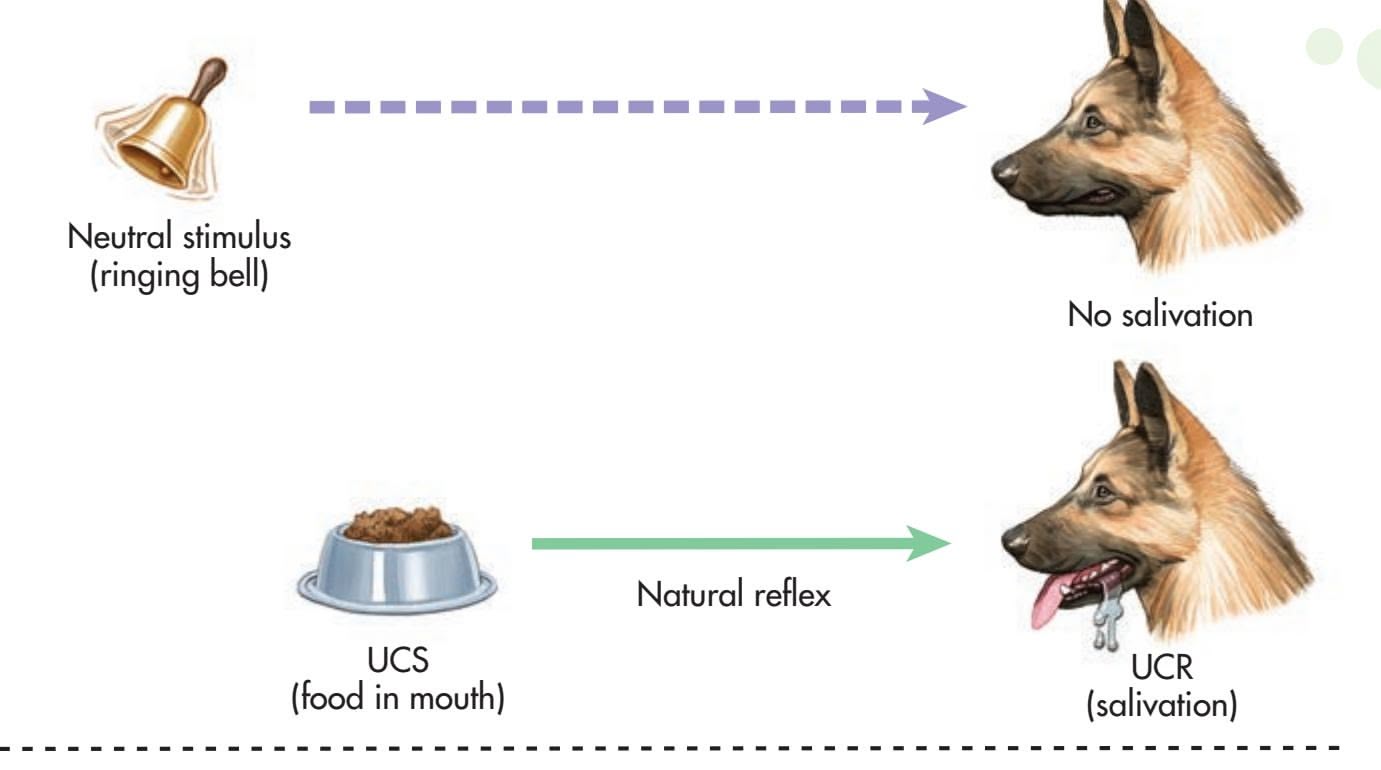

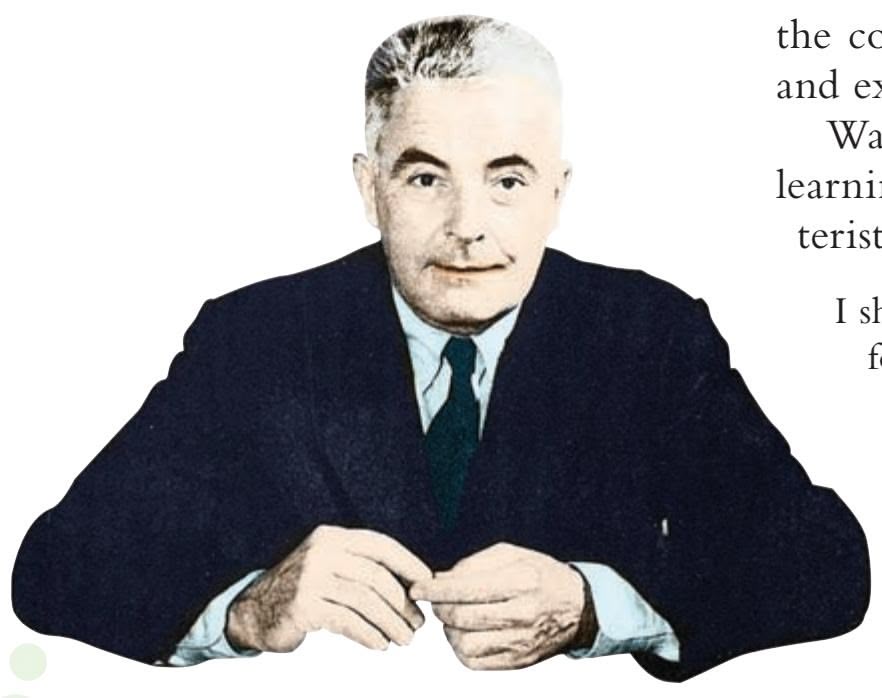

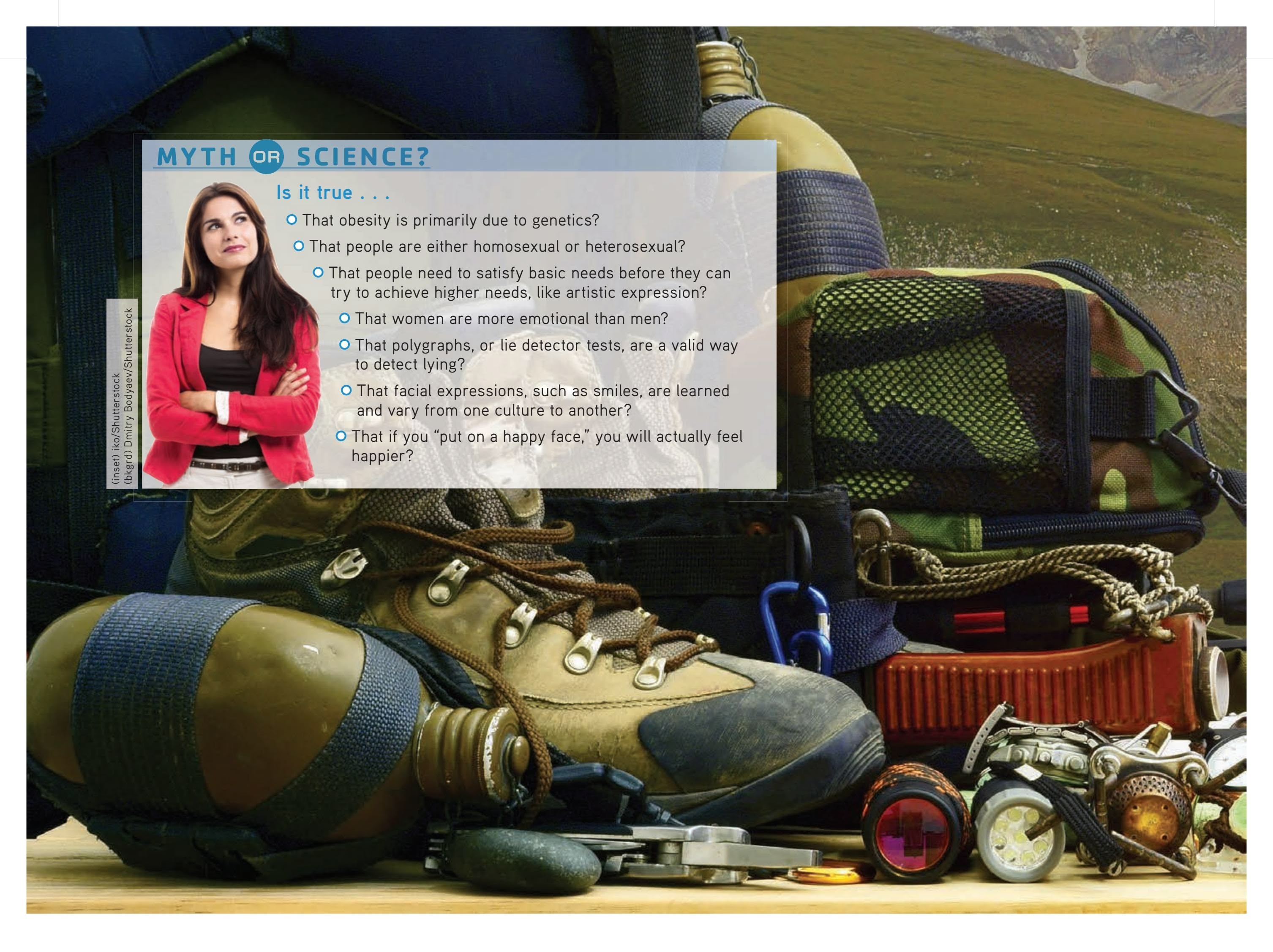

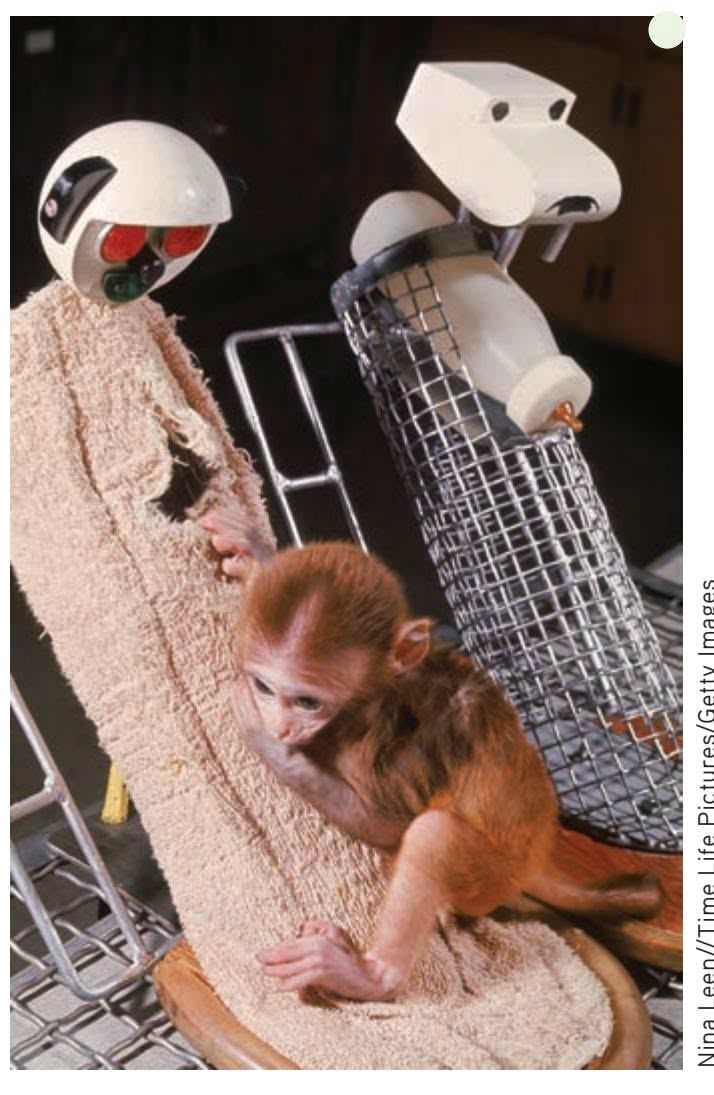

Behaviorism is another example of the influence of physiology on psychology. Behaviorism grew out of the pioneering work of a Russian physiologist named **Ivan Pavlov.** Pavlov demonstrated that dogs could learn to associate a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, with an automatic behavior, such as reflexively salivating to food. Once an association between the sound of the bell and the food was formed, the sound of the bell alone would trigger the salivation reflex in the dog. Pavlov enthusiastically believed he had discovered the mechanism by which all behaviors were learned.

In the United States, a young, dynamic psychologist named **John B. Watson** shared Pavlov's enthusiasm. Watson (1913) championed behaviorism as a new school of psychology. Structuralism was still an influential perspective, but Watson strongly objected to both its method of introspection and its focus on conscious mental processes. As Watson (1924) wrote in his classic book, *Behaviorism:*

Behaviorism, on the contrary, holds that the subject matter of human psychology *is the behavior of the human being.* Behaviorism claims that consciousness is neither a definite nor a usable concept. The behaviorist, who has been trained always as an experimentalist, holds, further, that belief in the existence of consciousness goes back to the ancient days of superstition and magic.

Behaviorism's influence on American psychology was enormous. The goal of the behaviorists was to discover the fundamental principles of *learning*—how behavior is

> acquired and modified in response to environmental influences. For the most part, the behaviorists studied animal behavior under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

> Although Watson left academic psychology in the early 1920s, behaviorism was later championed by an equally force-

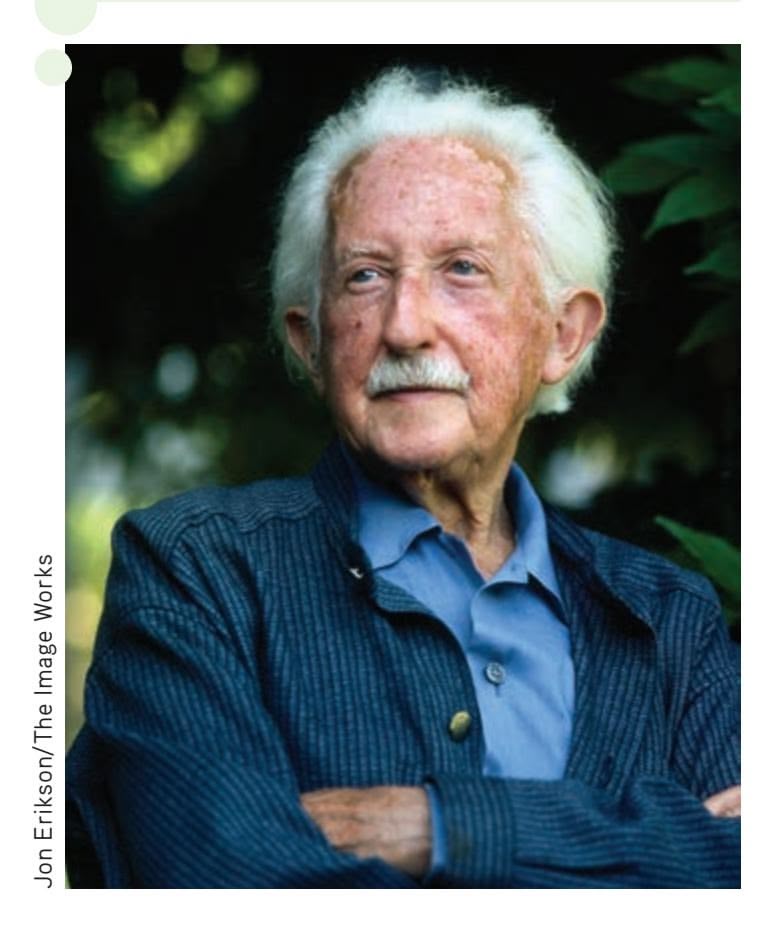

ful proponent—the famous American psychologist **B. F. Skinner.** Like Watson, Skinner believed that psychology should restrict itself to studying outwardly observable behaviors that could be measured and verified. In compelling experimental demonstrations, Skinner systematically used reinforcement or punishment to shape the behavior of rats and pigeons.

**B. F. Skinner (1904–1990)**

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 8 11/20/15 11:58 AM

Contemporary Psychology 9

**Carl Rogers (1902–1987)**

Between Watson and Skinner, behaviorism dominated American psychology for almost half a century. During that time, the study of conscious experiences was largely ignored as a topic in psychology (Baars, 2005). In Chapter 5 on learning, we'll [look at the lives and contribution](#page--1-0)s of Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner in greater detail.

**humanistic psychology** School of psychology and theoretical viewpoint that emphasizes each person's unique potential for psychological growth and self-direction.

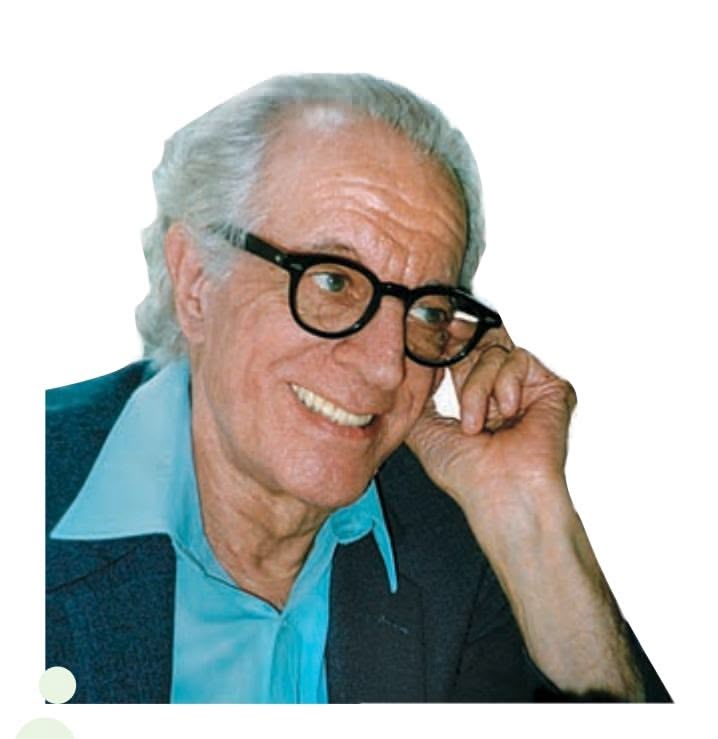

## Carl Rogers HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY

For several decades, behaviorism and psychoanalysis were the perspectives that most influenced the thinking of American psychologists. In the 1950s, a new school of thought emerged, called **humanistic psychology.** Because humanistic psychology was distinctly different from both psychoanalysis and behaviorism, it was sometimes referred to as the "third force" in American psychology (Waterman, 2013; Watson & others, 2011).

Humanistic psychology was largely founded by American psychologist **Carl Rogers** (Elliott & Farber, 2010). Like Freud, Rogers was influenced by his experiences with his psychotherapy clients. However, rather than emphasizing unconscious conflicts, Rogers emphasized the *conscious* experiences of his clients, including each person's unique

potential for psychological growth and self-direction. In contrast to the behaviorists, who saw human behavior as being shaped and maintained by external causes, Rogers emphasized self-determination, free will, and the importance of choice in human behavior (Elliott & Farber, 2010; Kirschenbaum & Jourdan, 2005).

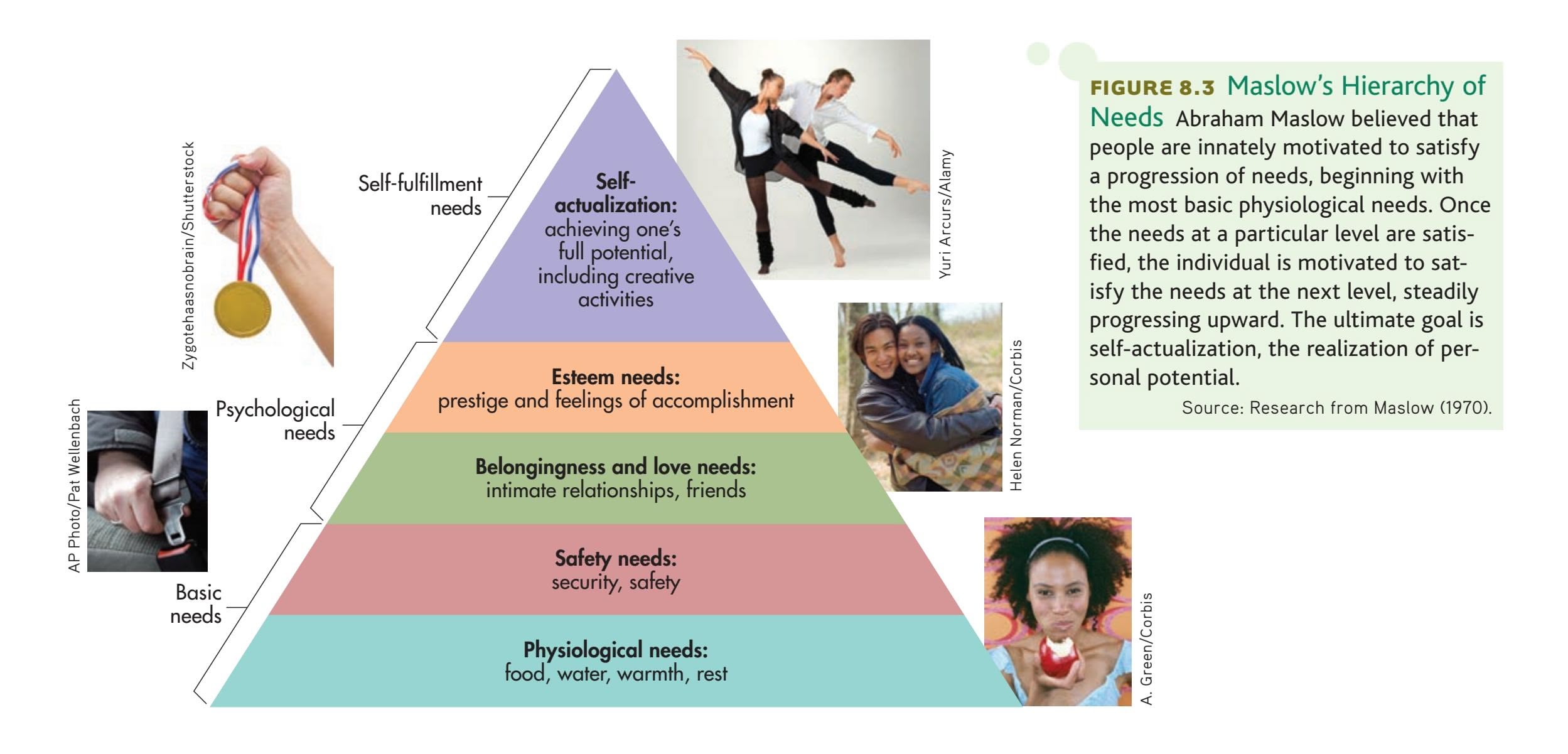

**Abraham Maslow** was another advocate of humanistic psychology. Maslow developed a theory of motivation that emphasized psychological growth, which we'll discuss in Chapter 8. Like psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology included not only influential theories of personality but also a form of psychotherapy, which we'll discuss in later chapters.

By briefly stepping backward in time, you've seen how the debates among the key thinkers in psychology's history shaped the development of psychology as a whole. Each of the schools that we've described had an impact on the topics and methods of psychological research. As you'll see throughout this textbook, that impact has been a lasting one. In the next sections, we'll touch on some of the more recent developments in psychology's evolution. We'll also explore the diversity that characterizes contemporary psychology.

❯ [Test your understanding of](#page--1-0) **The Origins of Psychology** with .

**Abraham Maslow (1908–1970)**

**Two Leaders in the Development of Humanistic Psychology** Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow were key figures in establishing humanistic psychology. Humanistic psychology emphasized the importance of selfdetermination, creativity, and human potential (Serlin, 2012). The ideas of Carl Rogers have been particularly influential in modern psychotherapy. Abraham Maslow's theory of motivation emphasized the importance of psychological growth.

(l) Special Collections, Donald C. Davidson Library/University of California, Santa Barbara (r) Courtesy of Robert D. Farber University Archives at Brandeis University

# Contemporary Psychology

## KEY THEME

As psychology has developed as a scientific discipline, the topics it investigates have become progressively more diverse.

#### KEY QUESTIONS

- ❯ How do the perspectives in contemporary psychology differ in emphasis and approach?

- ❯ How do psychiatry and psychology differ, and what are psychology's major specialty areas?

Over the past half-century, the range of topics in psychology has become progressively more diverse. And, as psychology's knowledge base has increased, psychology itself has become more specialized. Rather than being dominated by a particular approach or school of thought, today's psychologists tend to identify themselves according to: (1) the *perspective* they emphasize in investigating psychological topics and (2) the *specialty area* in which they have been trained and practice.

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 9 11/20/15 11:58 AM

10 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and [Research](#page--1-0) Methods

**neuroscience** The study of the nervous system, especially the brain.

## Major Perspectives in Psychology

Any given topic in contemporary psychology can be approached from a variety of perspectives. Each perspective discussed here represents a different emphasis or point of view that can be taken in studying a particular behavior, topic, or issue. As you'll see in this section, the influence of the early schools of psychology is apparent in the first four perspectives that characterize contemporary psychology.

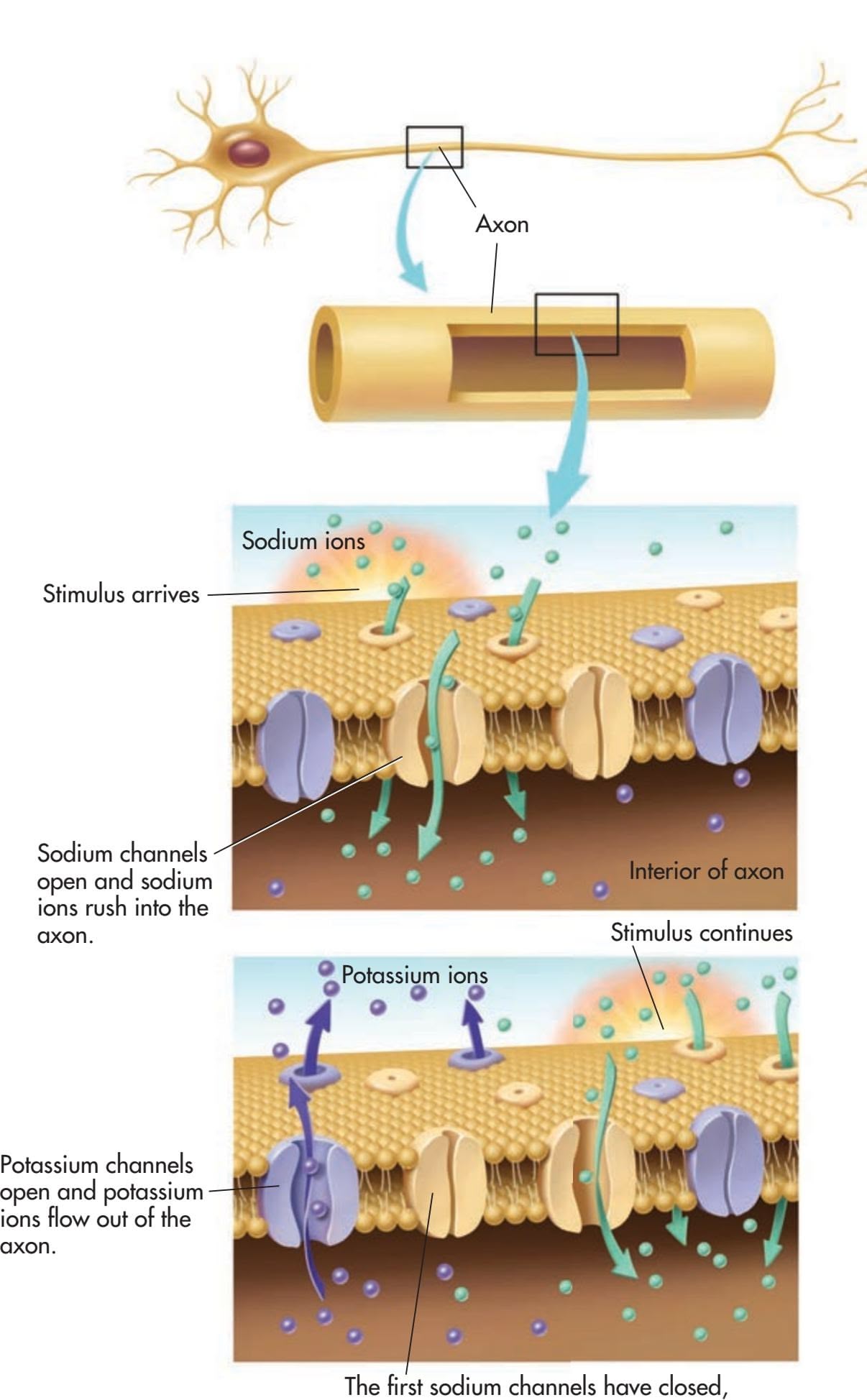

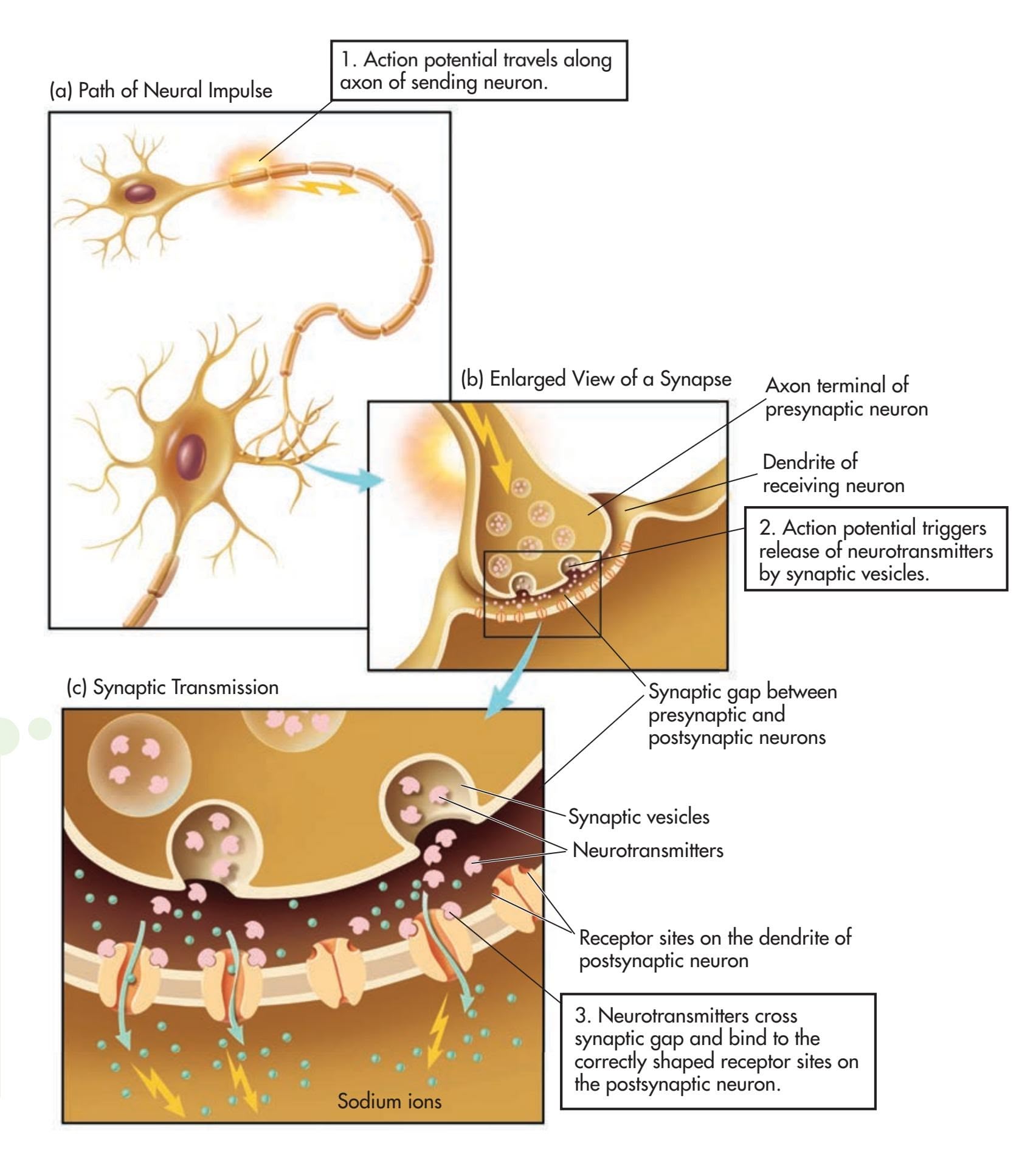

### THE BIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

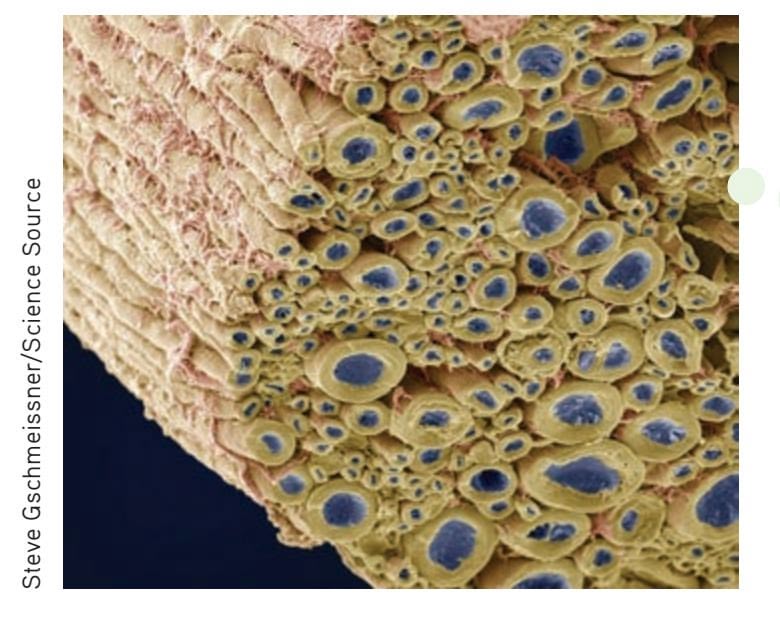

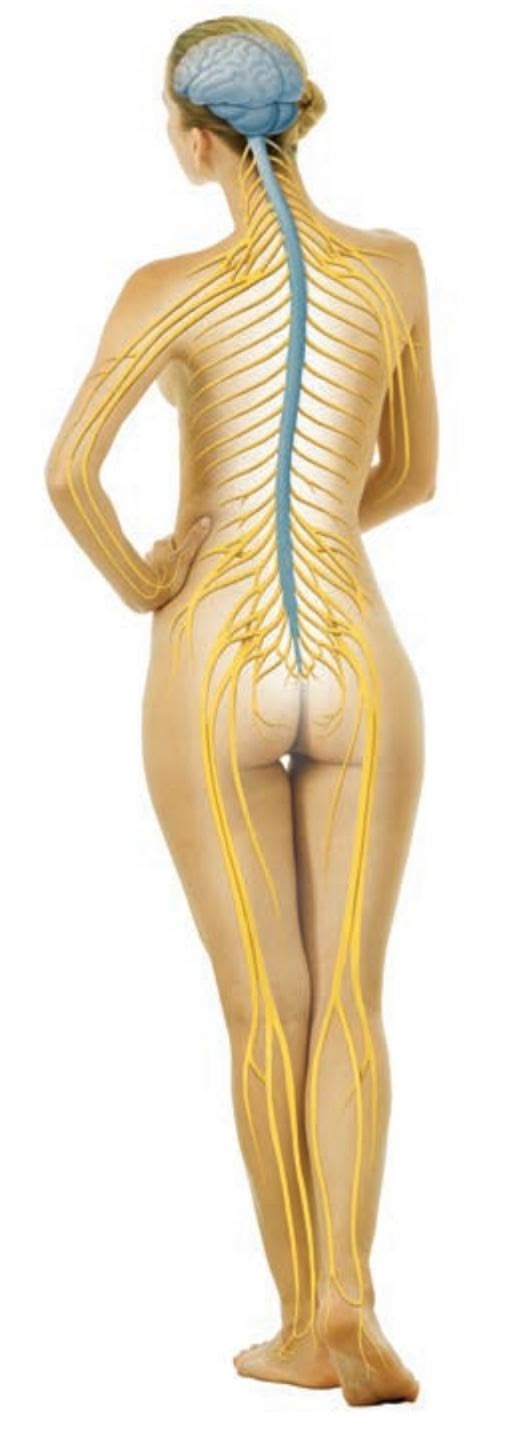

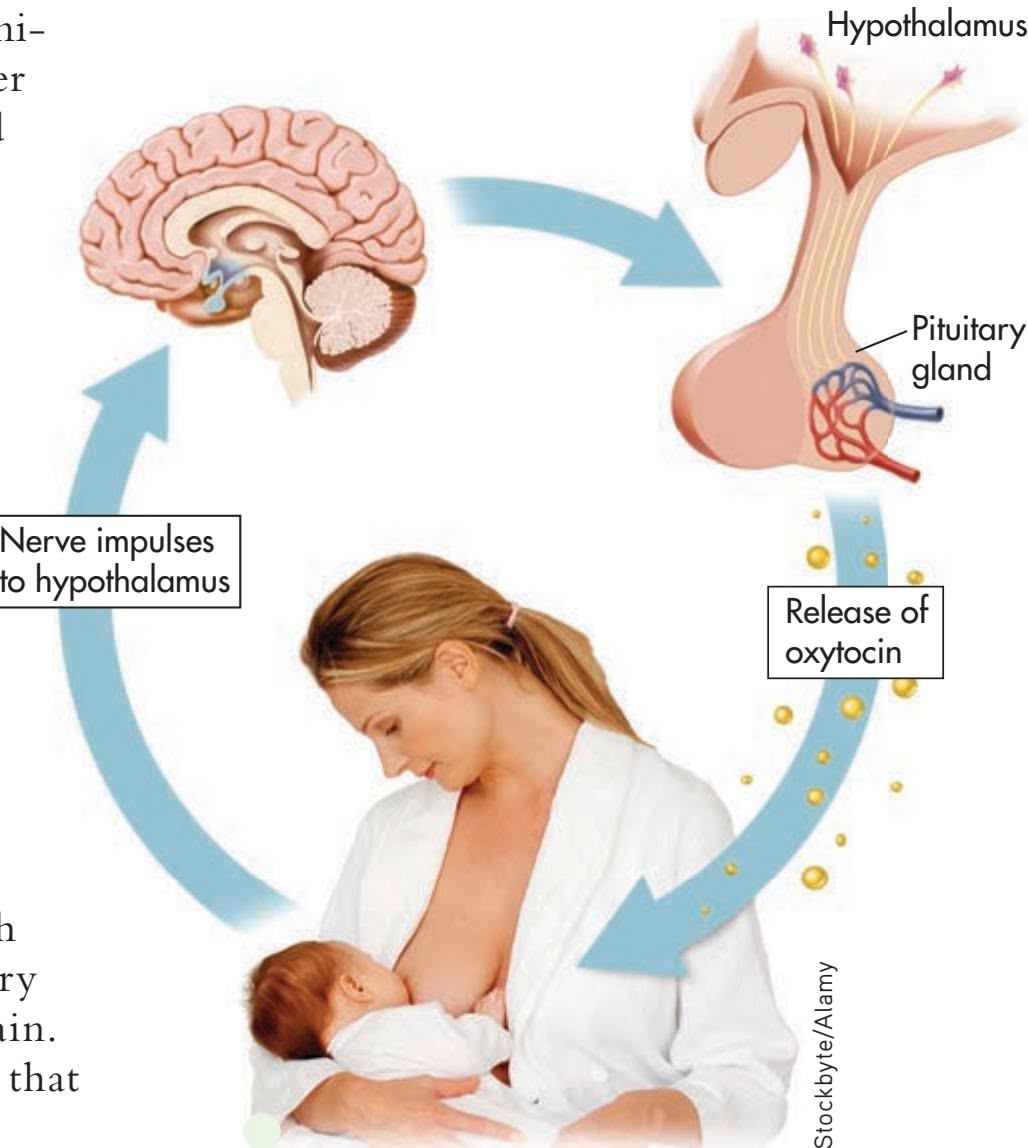

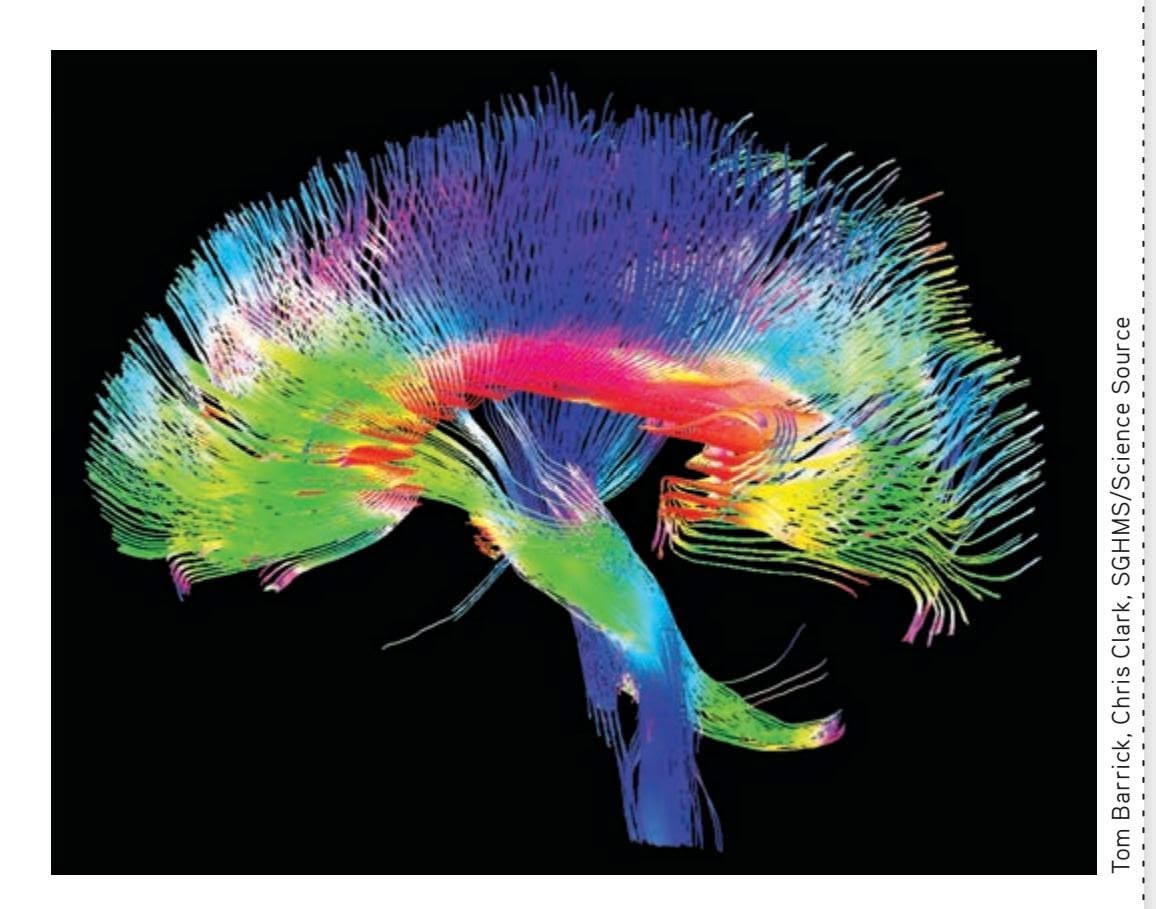

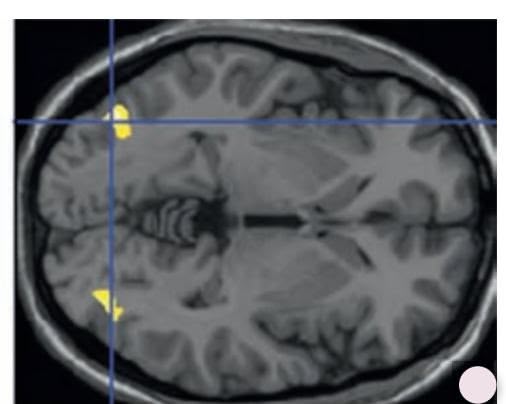

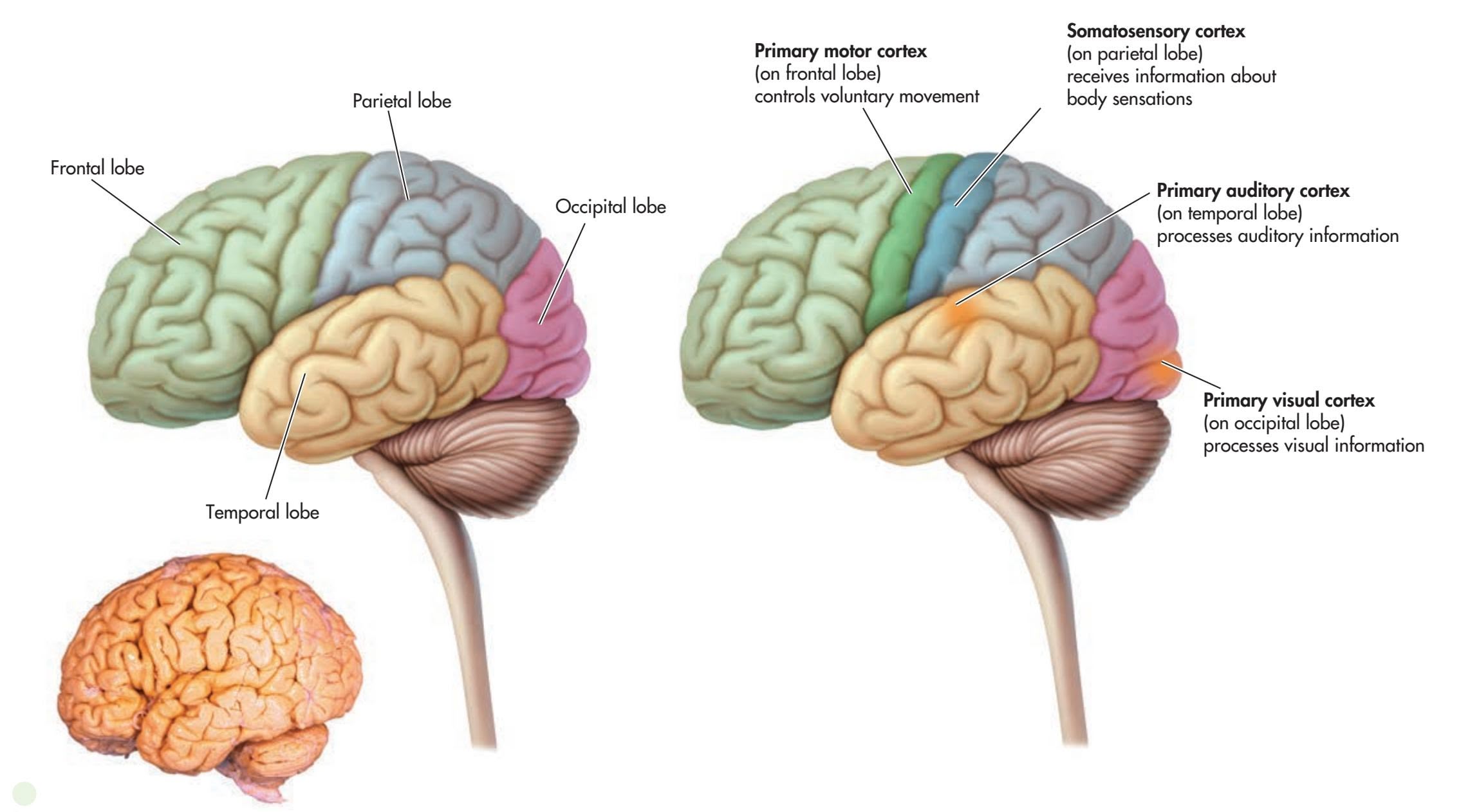

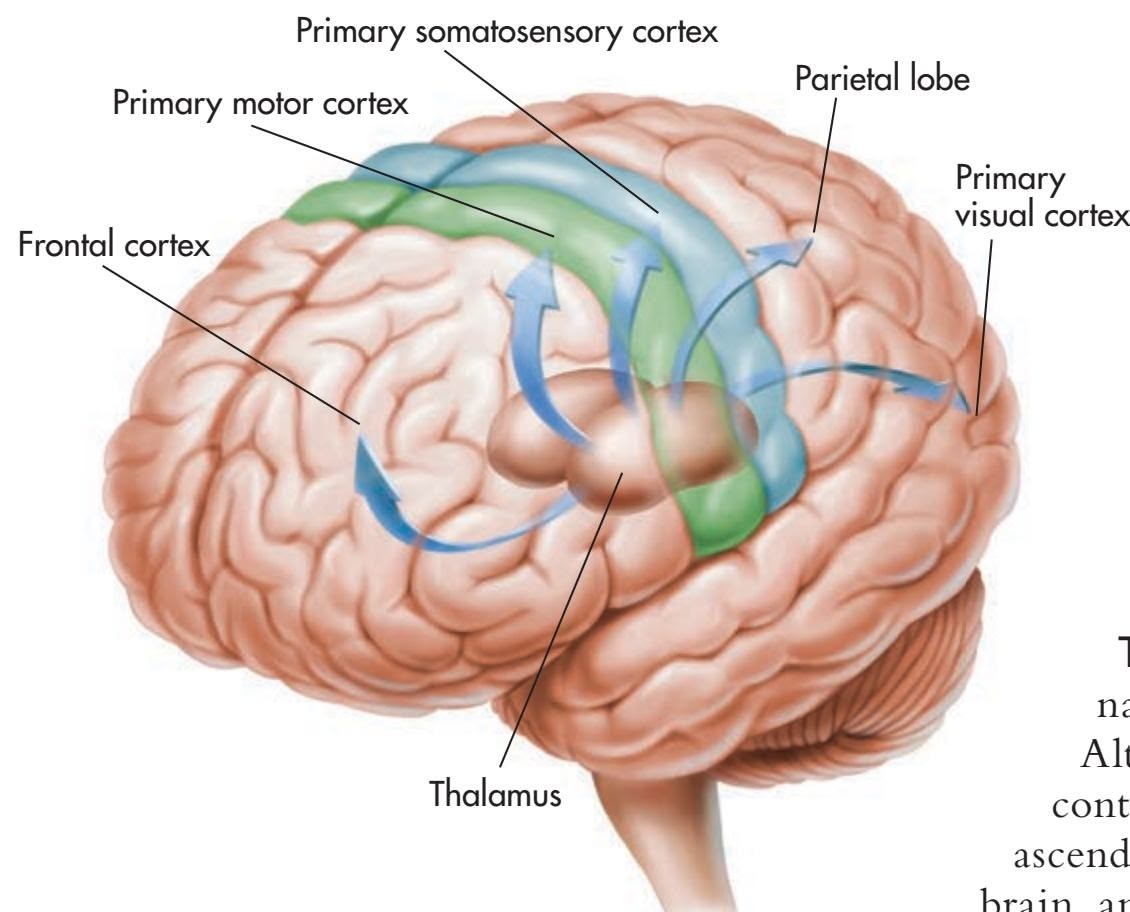

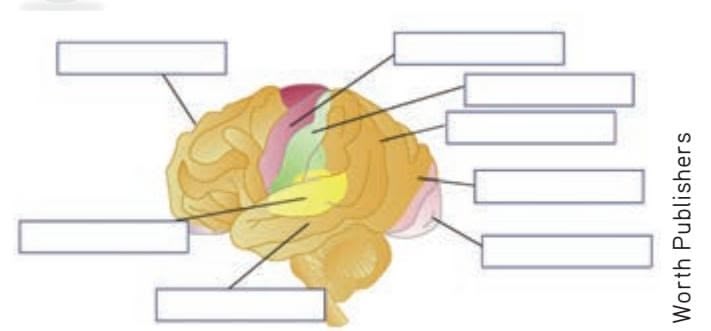

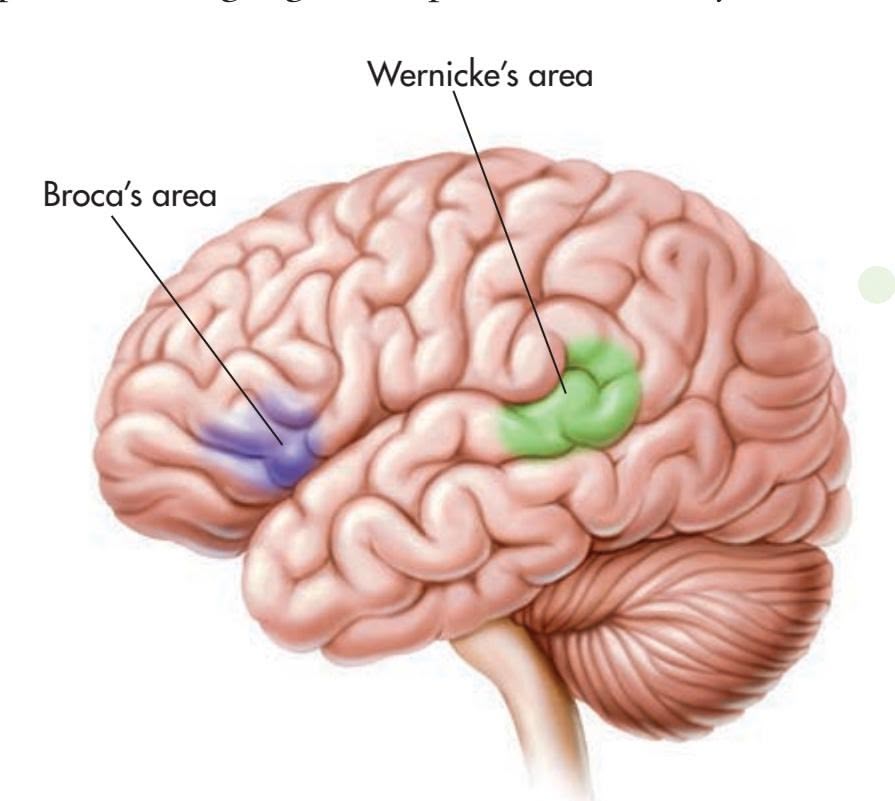

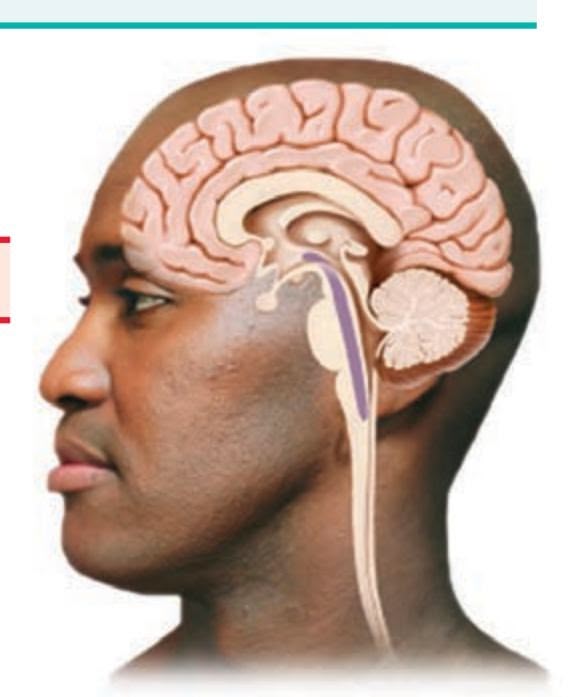

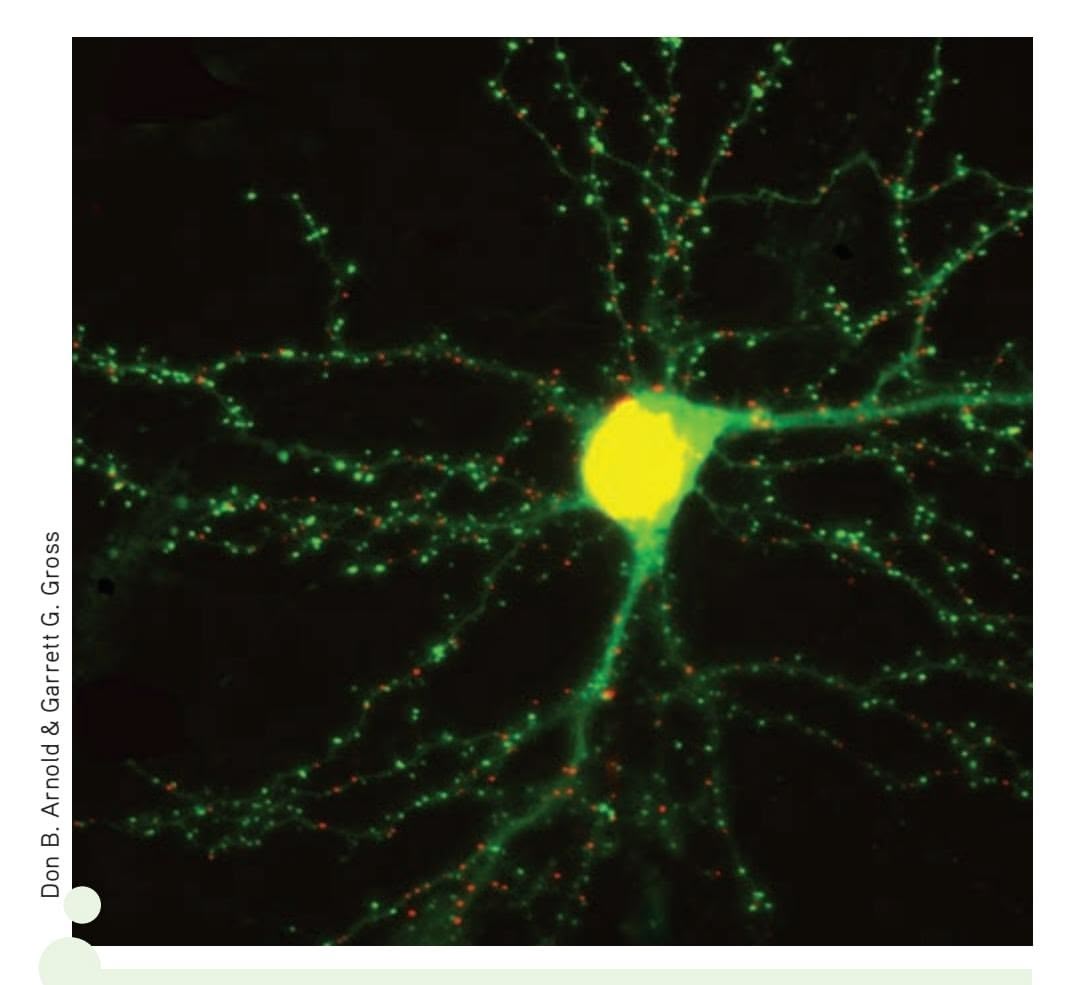

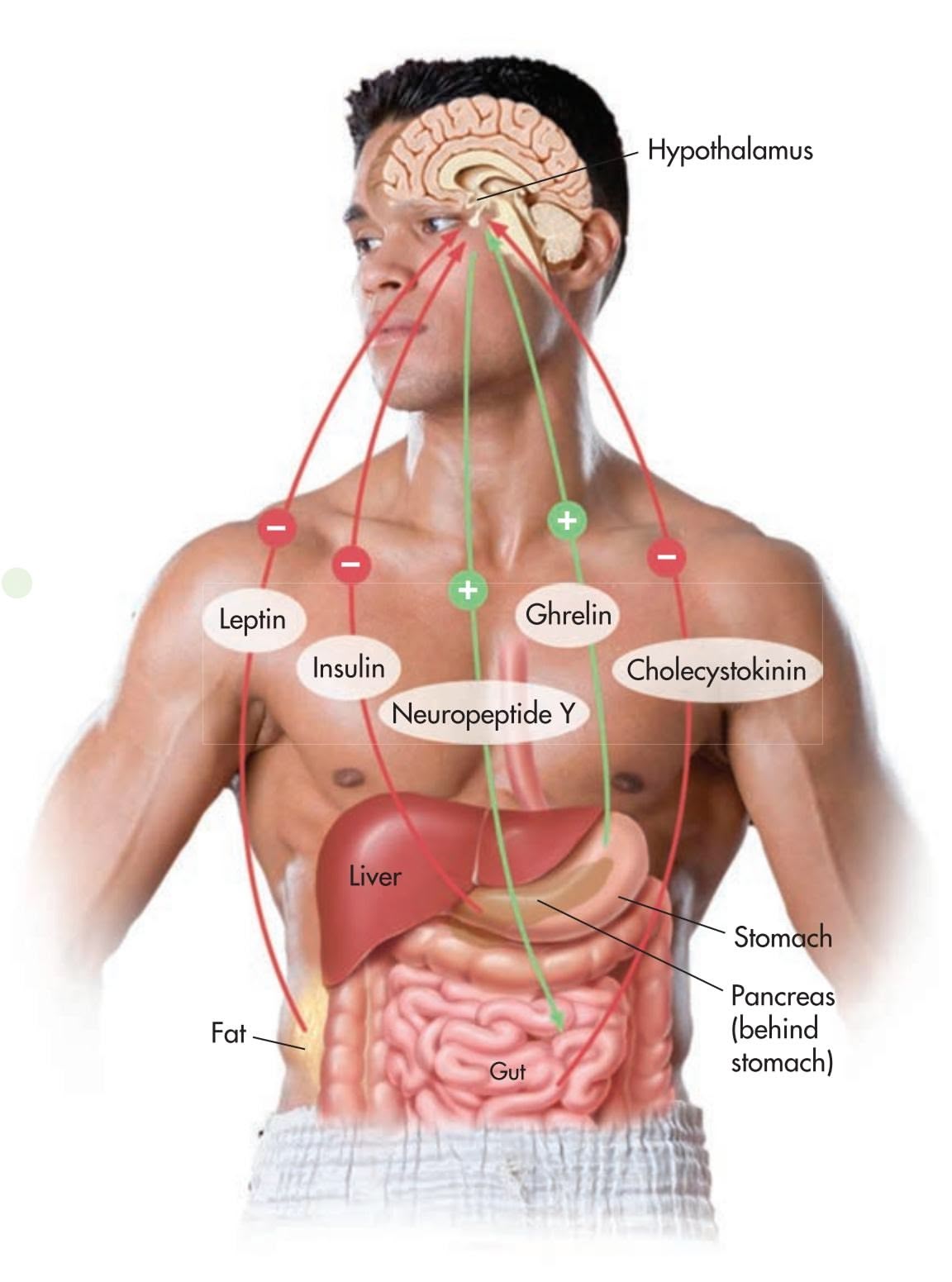

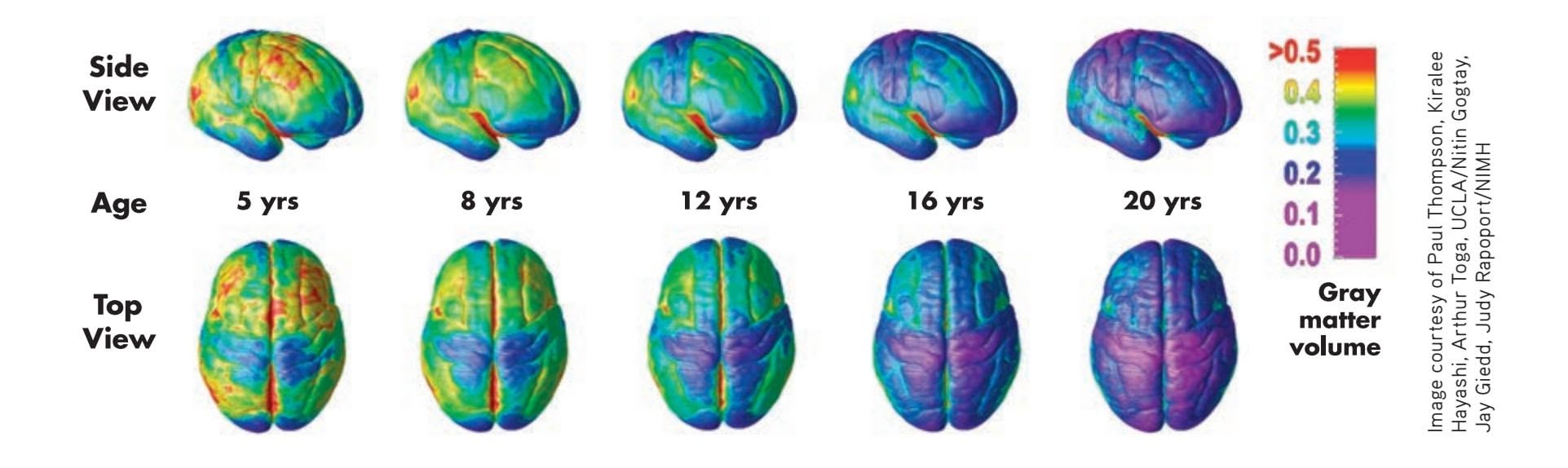

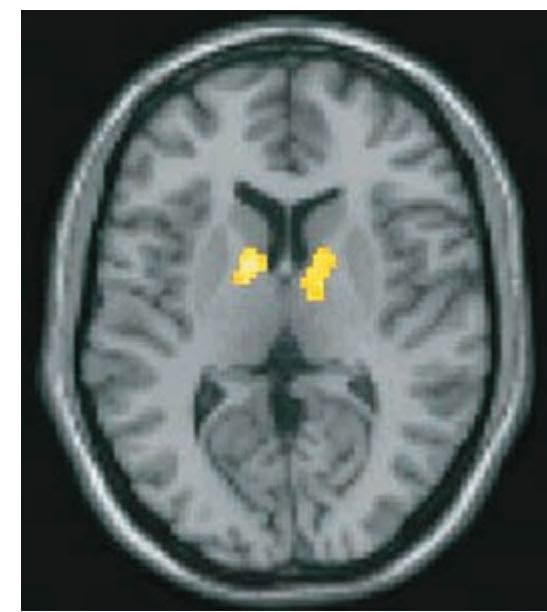

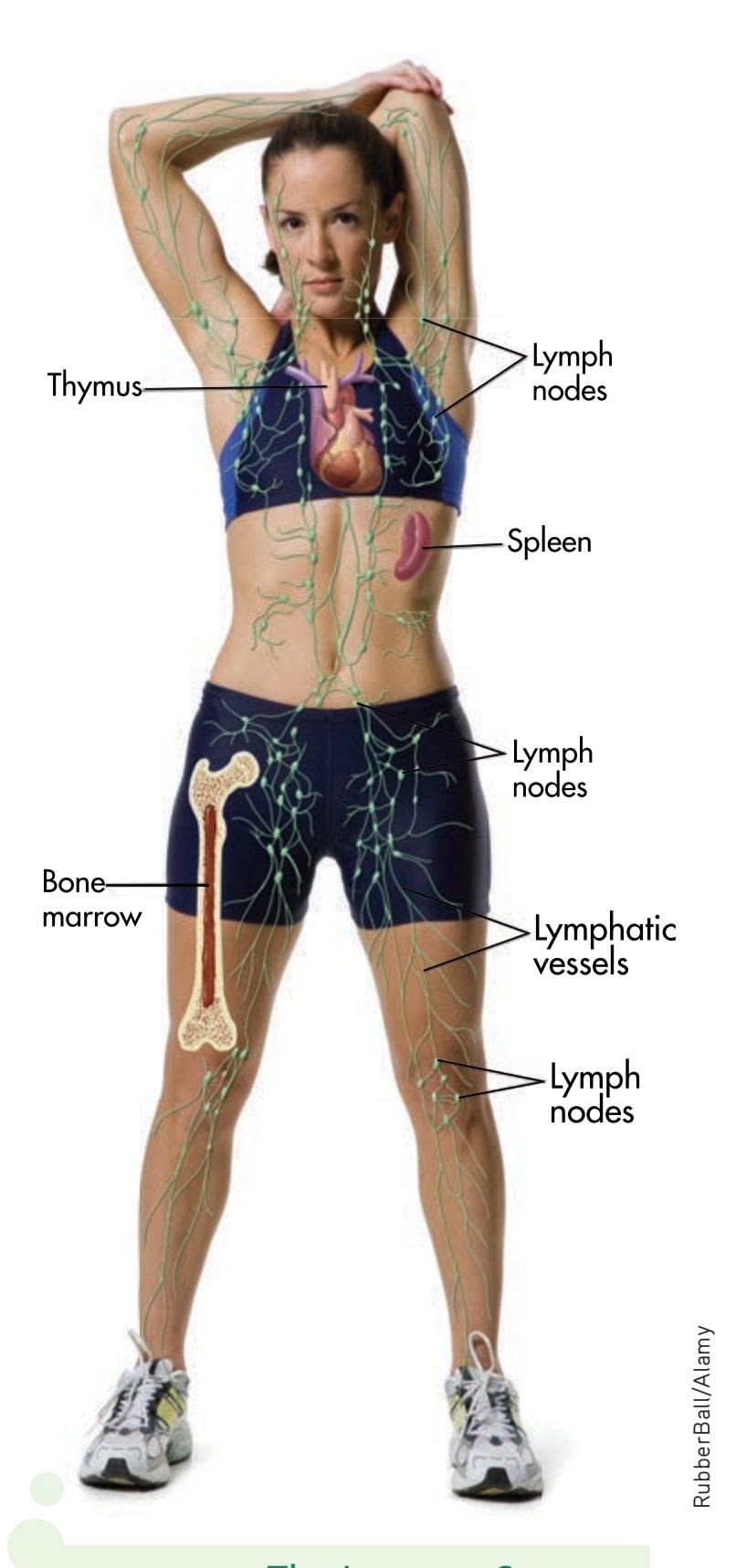

As we've already noted, physiology has played an important role in psychology since it was founded. Today, that influence continues, as is shown by the many psychologists who take the biological perspective. The *biological perspective* emphasizes studying the physical bases of human and animal behavior, including the nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, and genetics. More specifically, **neuroscience** refers to the study of the nervous system, especially the brain. Sophisticated brainscanning techniques, including the *PET scan, MRI scan,* and *functional MRI (fMRI) scan*, allow neuroscientists to study the structure and activity of the intact, living brain in increasing detail. Later in the chapter, we'll describe these brain-imaging techniques and explain how psychologists use them as research tools.

## THE PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

The key ideas and themes of Freud's landmark theory of psychoanalysis continue to be important among many psychologists, especially those working in the mental health field. As you'll see in Chapter 10 on personality, and Chapter 14 on therapies, many of Freud's ideas have been expanded or modified by his followers. Today, psychologists who take the *psychodynamic perspective* may or may not follow Freud or take a psychoanalytic approach. However, they do tend to emphasize the importance of unconscious influences, early life experiences, and interpersonal relationships in explaining the underlying dynamics of behavior or in treating people with psychological problems.

### THE BEHAVIORAL PERSPECTIVE

Watson and Skinner's contention that psychology should focus on observable behaviors and the fundamental laws of learning is evident today in the *behavioral perspective.* Contemporary psychologists who take the behavioral perspective continue to study

**The Biological Perspective** The physiological aspects of behavior and mental processes are studied by biological psychologists. Psychologists and other scientists who specialize in the study of the brain and the rest of the nervous system are called neuroscientists*.* Here, Swiss neuroscientist Juliane Britz uses a device called an *electroencephalogram* to monitor brain wave activity in a research participant. Dr. Britz studies the brain processes involved in sensation, perception, and awareness (Britz & others, 2014).

BSIP/Newscom

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 10 11/20/15 11:58 AM

Contemporary Psychology 11

how behavior is acquired or modified by environmental causes. Many psychologists who work in the area of mental health also emphasize the behavioral perspective in explaining and treating psychological disorders. In Chapter 5 on learning, and Chapter 14 on therapies, we'll discuss different applications of the behavioral perspective.

## THE HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVE

The influence of the work of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow continues to be seen among contemporary psychologists who take the humanistic perspective (Serlin, 2012; Waterman, 2013). The *humanistic perspective* focuses on the motivation of people to grow psychologically, the influence of interpersonal relationships on a person's selfconcept, and the importance of choice and self-direction in striving to reach one's potential. Like the psychodynamic perspective, the humanistic perspective is often emphasized among psychologists working in the mental health field. You'll encounter the humanistic perspective in the chapters on motivation (8), personality (10), and therapies (14).

## THE POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PERSPECTIVE

The humanistic perspective's emphasis on psychological growth and human potential contributed to the recent emergence of a new perspective. **Positive psychology** is a field of psychological research and theory focusing on the study of positive emotions and psychological states, positive individual traits, and the social institutions that foster those qualities in individuals and communities (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011; Peterson, 2006; Seligman & others, 2005). By studying the conditions and processes that contribute to the optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions, positive psychology seeks to counterbalance psychology's traditional emphasis on psychological problems and disorders (McNulty & Fincham, 2012).

Topics that fall under the umbrella of positive psychology include personal happiness, optimism, creativity, resilience, character strengths, and wisdom. Positive psychology is also focused on developing therapeutic techniques that increase personal well-being rather than just alleviating the troubling symptoms of psychological disorders (Snyder & others, 2011). Insights from positive psychology research will be evident in many chapters, including the chapters on motivation and emotion (8); personality (10); stress, health, and coping (12); and therapies (14).

### THE COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

During the 1960s, psychology experienced a return to the study of how mental processes influence behavior. Often referred to as "the cognitive revolution" in psychology, this movement represented a break from traditional behaviorism. Cognitive psychology focused once again on the important role of mental processes in how people process and remember information, develop language, solve problems, and think.

The development of the first computers in the 1950s contributed to the cognitive revolution. Computers gave psychologists a new model for conceptualizing human mental processes—human thinking, memory, and perception could be understood in terms of an information-processing model. We'll consider the cognitive perspective in several chapters, including Chapter 7 on thinking, language, and intelligence. The cognitive perspective has also influenced other areas of psychology, including personality (Chapter 10) and psychotherapy (Chapter 14).

## THE CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

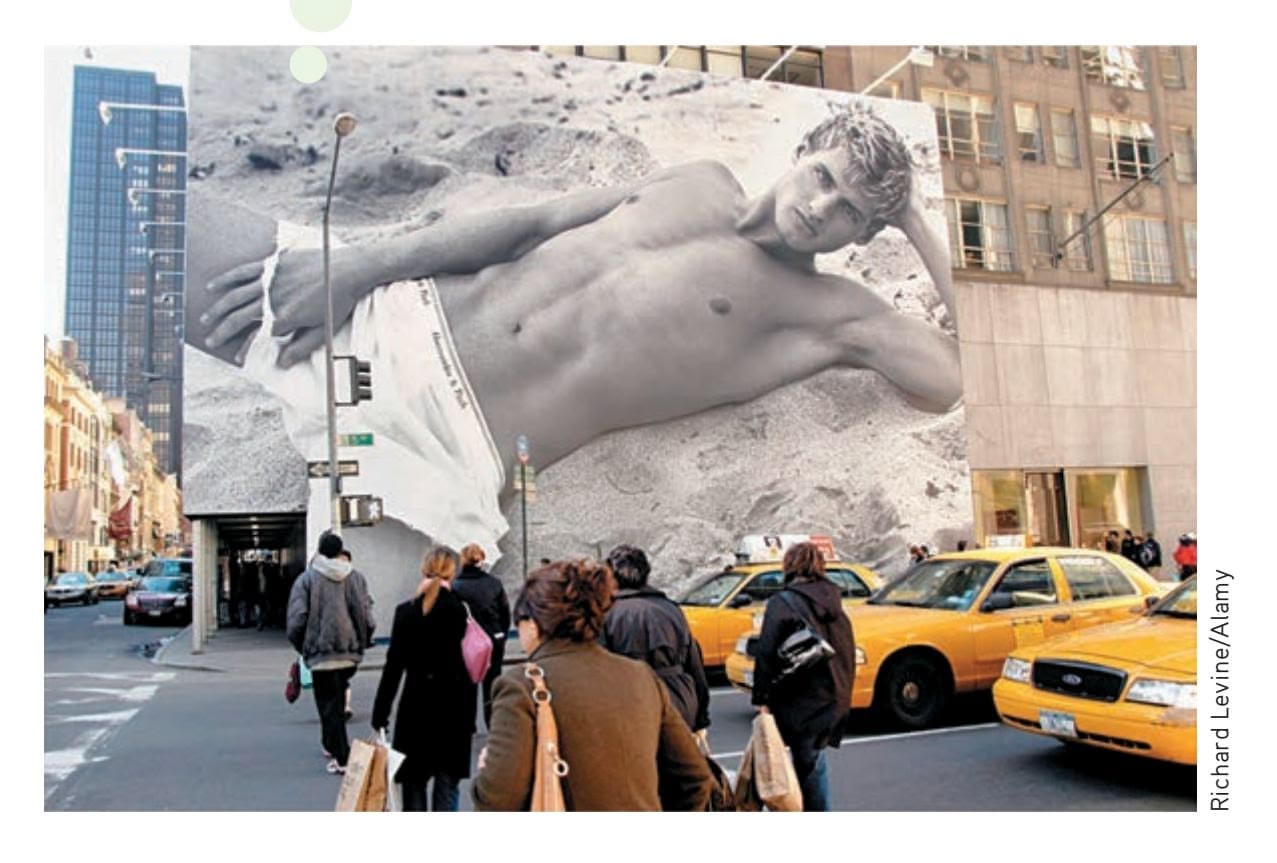

More recently, psychologists have taken a closer look at how cultural factors influence patterns of behavior—the essence of the *cross-cultural perspective.* By the late 1980s, *cross-cultural psychology* had emerged in full force as large numbers of

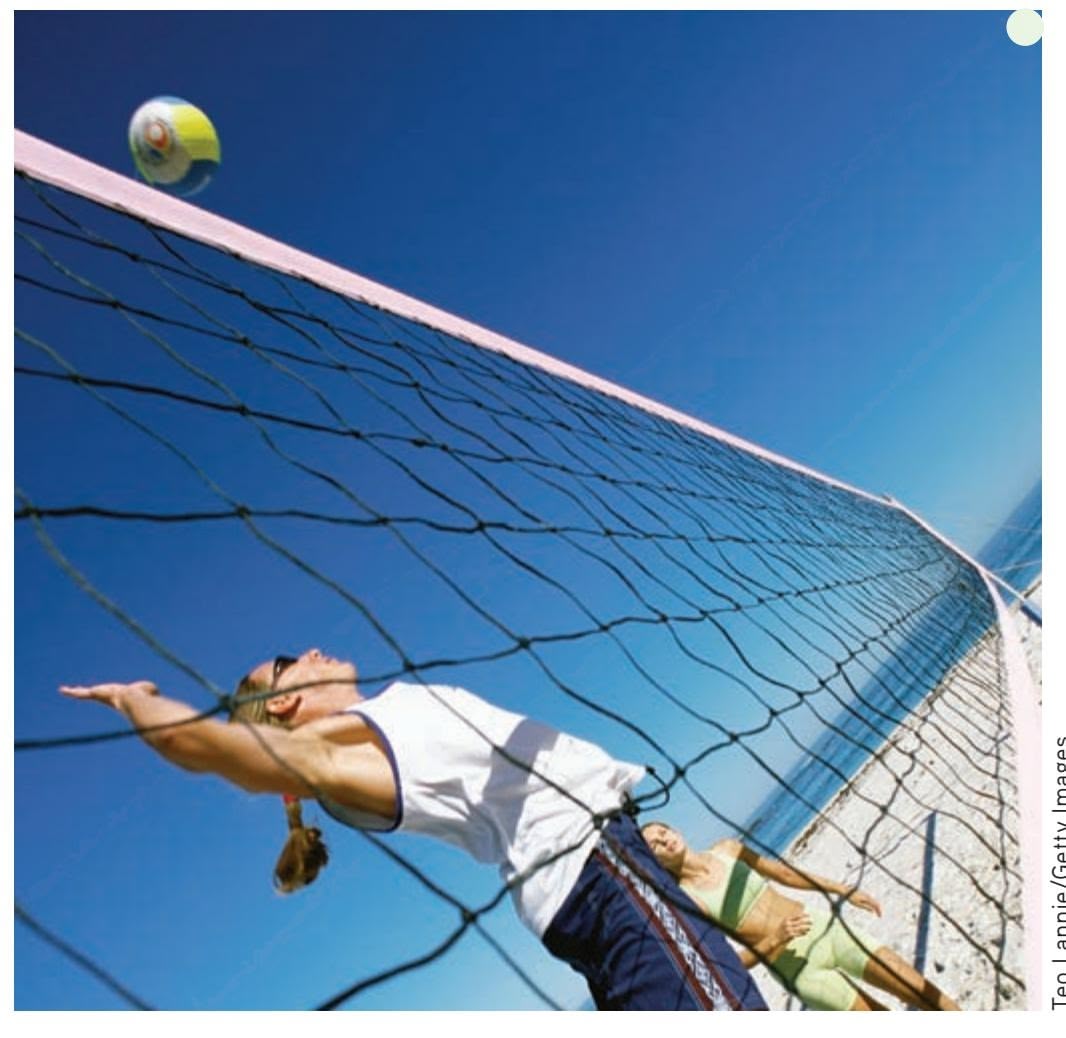

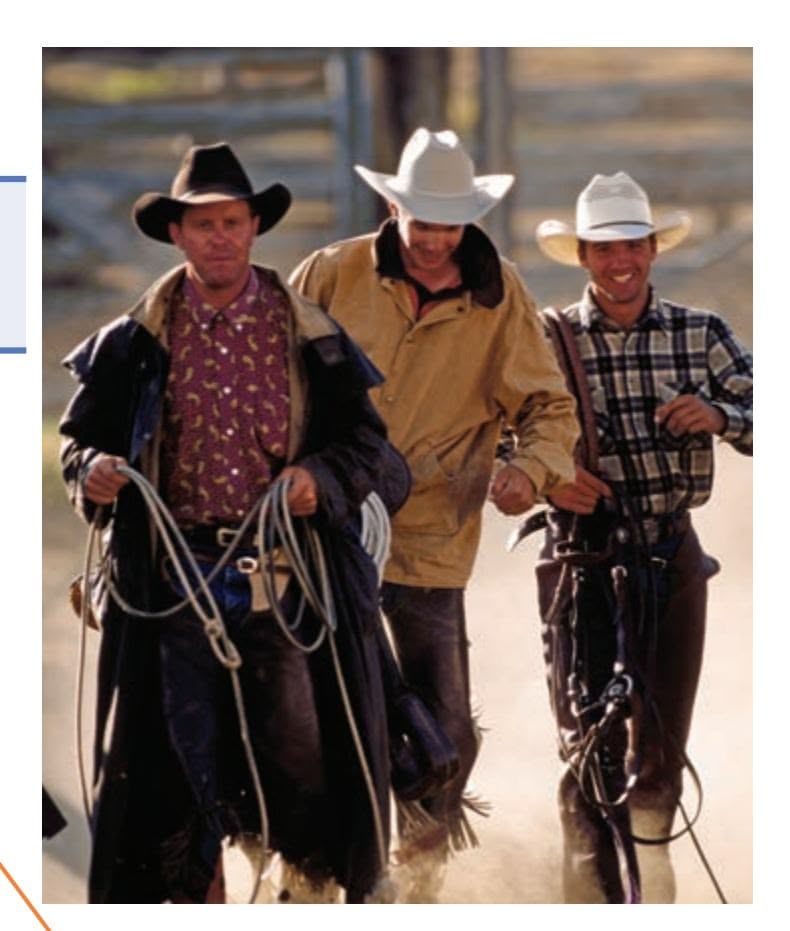

**Studying Behavior from Different Psychological Perspectives** Psychologists can study a particular behavior, topic, or issue from different perspectives. For example, taking the biological perspective, a psychologist might study whether there are biological differences between rock climbers and other people, such as the ability to stay calm and focused in the face of dangerous situations. A psychologist taking the behavioral perspective might look at how people learn to climb and the types of rewards that reinforce their climbing behavior. And, a psychologist who took the positive psychology perspective might investigate how meeting the challenge of climbing a difficult and dangerous route contributed to selfconfidence and personal growth.

Greg Epperson/Getty Images

**positive psychology** The study of positive emotions and psychological states, positive individual traits, and the social institutions that foster positive individuals and communities.

12 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

## **[c](#page--1-0) [uLturE And HuM](#page--1-0) [An BEHAVIor](#page--1-0)**

## What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology?

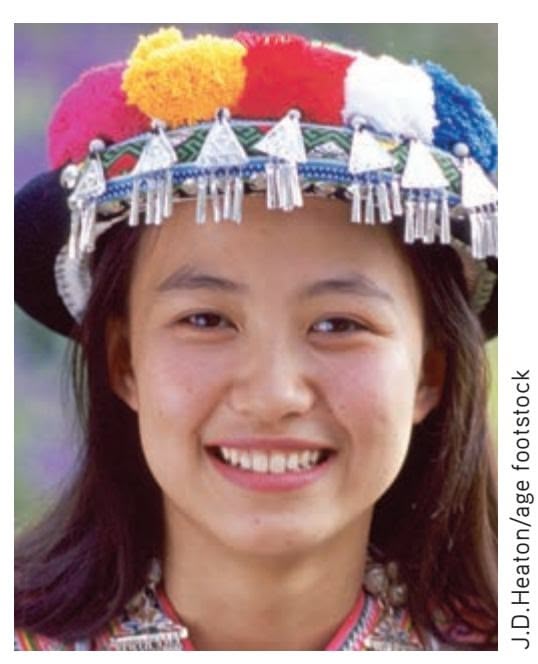

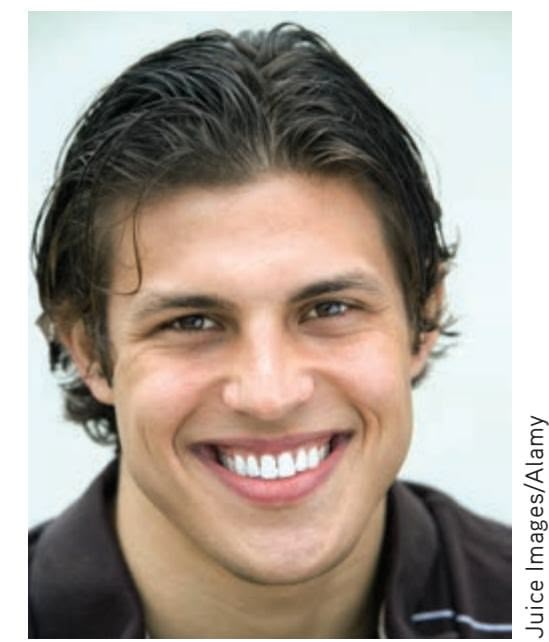

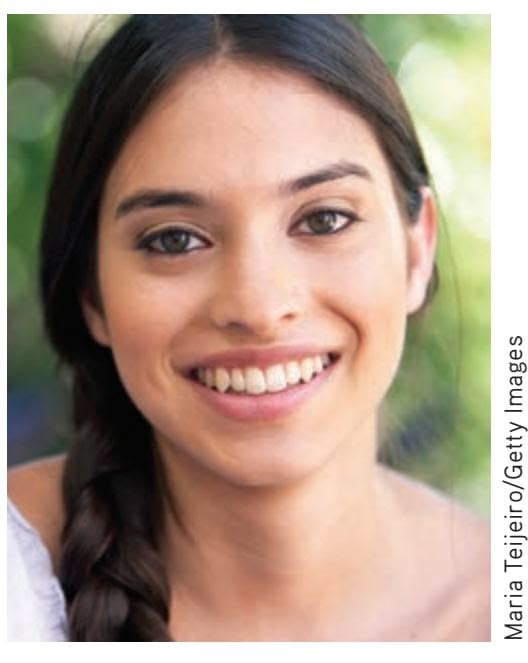

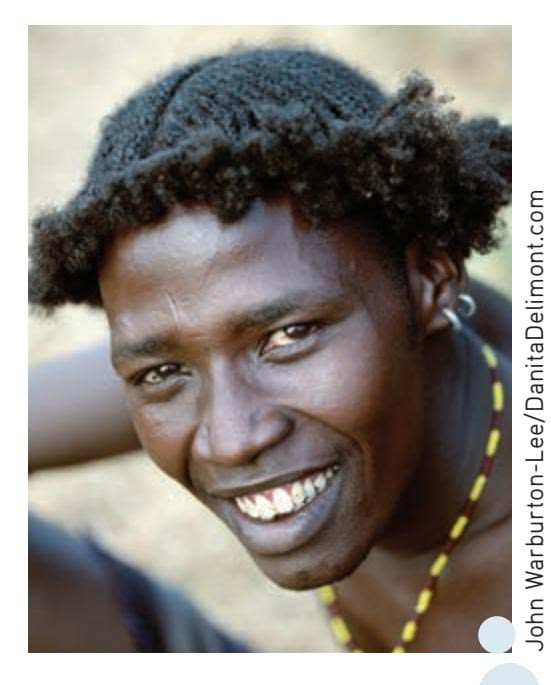

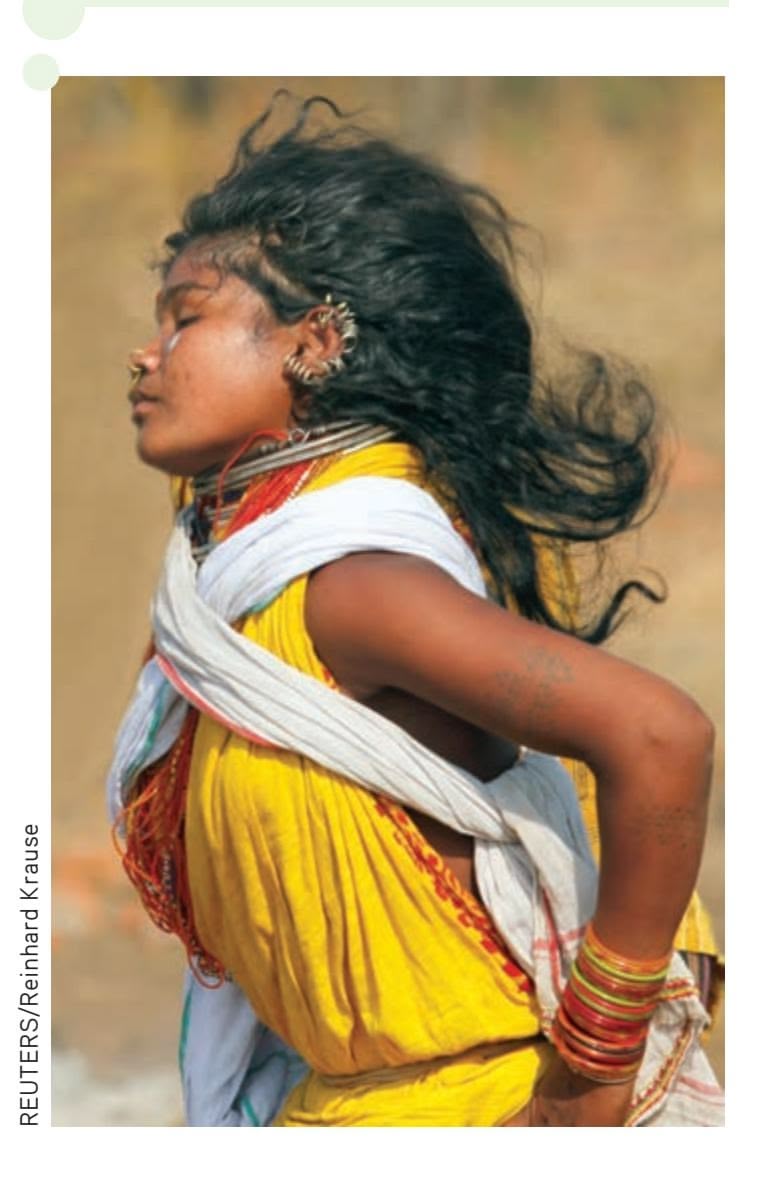

People around the globe share many attributes: We all eat, sleep, form families, seek happiness, and mourn losses. Yet the *way* in which we express our human qualities can vary considerably among cultures (Triandis, 2005). *What* we eat, *where* we sleep, and *how* we form families, define happiness, and express sadness can differ greatly in different cultures.

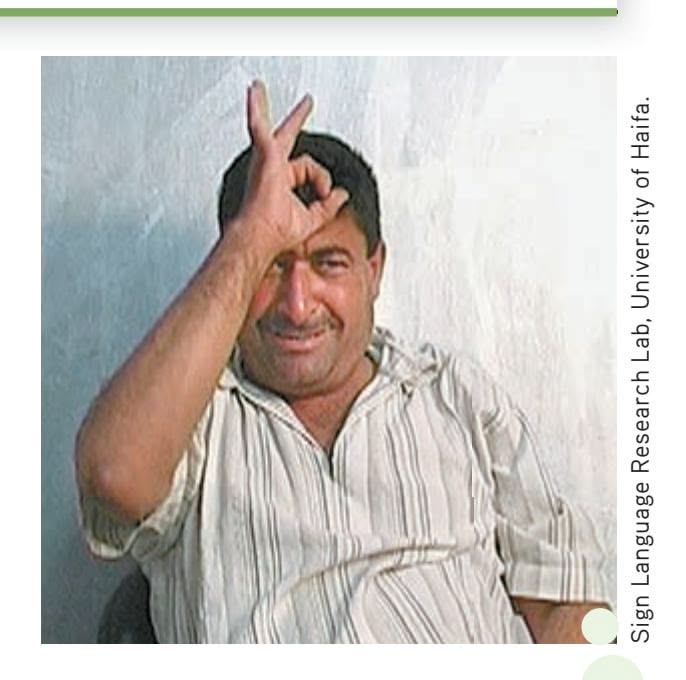

**Culture** refers to the attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to another (Cohen, 2009, 2010). Studying the differences among cultures and the influences of culture on behavior are the fundamental goals of **cross-cultural psychology.**

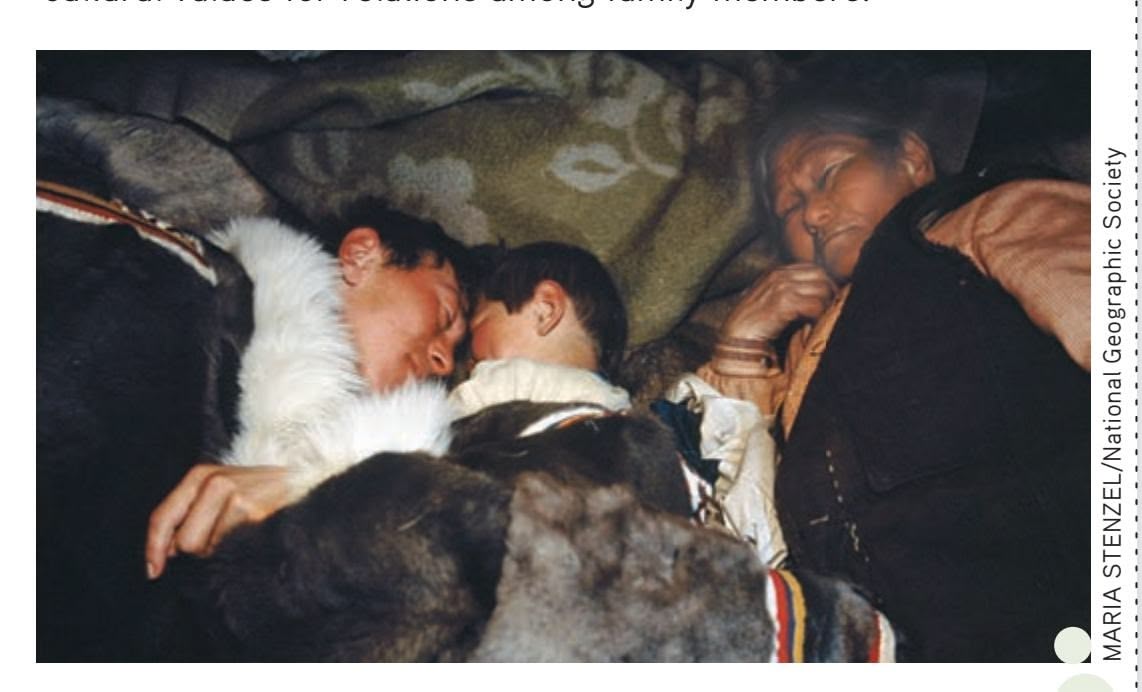

Cultural identity is influenced by many factors, including ethnicity, nationality, race, religion, and language. As we grow up within a given culture, we learn our culture's *norms,* or unwritten rules of behavior. And, we tend to act in accordance with those internalized norms without thinking. For example, according to the dominant cultural norms in the United States, babies usually sleep separately from their parents. But in many cultures around the world, it's taken for granted that babies will sleep in the same bed as their parents (Mindell & others, 2010a, b). Members of these other cultures are often surprised and even shocked at the U.S. practice of separating babies from their parents at night. (In Chapter 9 on lifespan development, we discuss this topic at greater length.)

The tendency to use your own culture as the standard is called **ethnocentrism.** Ethnocentrism may be a natural tendency, but it can prevent us from understanding the behaviors of others (Bizumic & others, 2009). Ethnocentrism may also prevent us from being aware of how our behavior has been shaped by our own culture.

Extreme ethnocentrism can lead to intolerance toward other cultures. If we believe that our way of seeing things or behaving is the only proper one, other ways of behaving and thinking may seem laughable, inferior, wrong, or even immoral.

In addition to influencing how we behave, culture affects how we define our sense of self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998, 2010). For the most part, the dominant cultures of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe can be described as individualistic cultures. **Individualistic cultures** emphasize the needs and goals of the individual over the needs and goals of the group (Henrich, 2014; Markus & Kitayama, 2010). In individualistic societies, the self is seen as *independent,* autonomous, and distinctive. Personal identity is defined by individual achievements, abilities, and accomplishments.

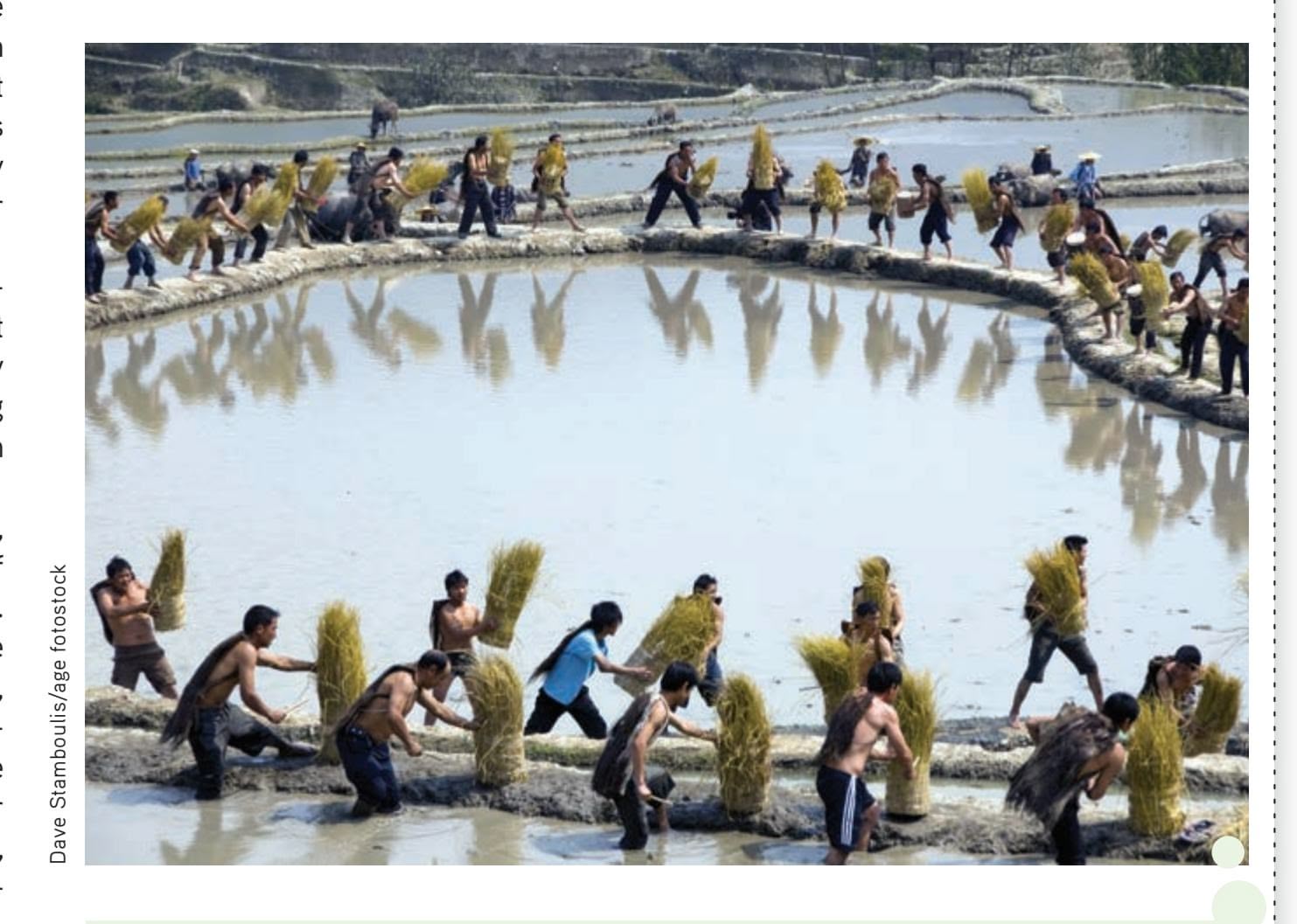

In contrast, **collectivistic cultures** emphasize the needs and goals of the group over those of the individual. Social behavior is more heavily influenced by cultural norms and social context than by individual preferences and attitudes (Owe & others, 2013; Talhelm & others, 2014). In a collectivistic culture, the self is seen as being much more *interdependent* with others. Relationships with others and identification with a larger group, such as the family or tribe, are key components of personal identity. The cultures of Asia, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America tend to be collectivistic. About two-thirds of the world's population live in collectivistic cultures (Triandis, 2005).

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic societies is useful in cross-cultural psychology. However, most cultures are neither completely individualistic nor completely collectivistic, but fall somewhere between the two extremes. And, psychologists are careful not to assume that these generalizations are true of every member or every aspect of a given culture (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011). Psychologists also recognize that there is a great deal of individual variation among the members of every culture (Heine & Norenzayan, 2006). It's important to keep that qualification in mind when cross-cultural findings are discussed.

The Culture and Human Behavior boxes that we have included in this book will help you learn about human behavior in other cultures. They will also help you understand how culture affects *your* behavior, beliefs, attitudes, and values as well.

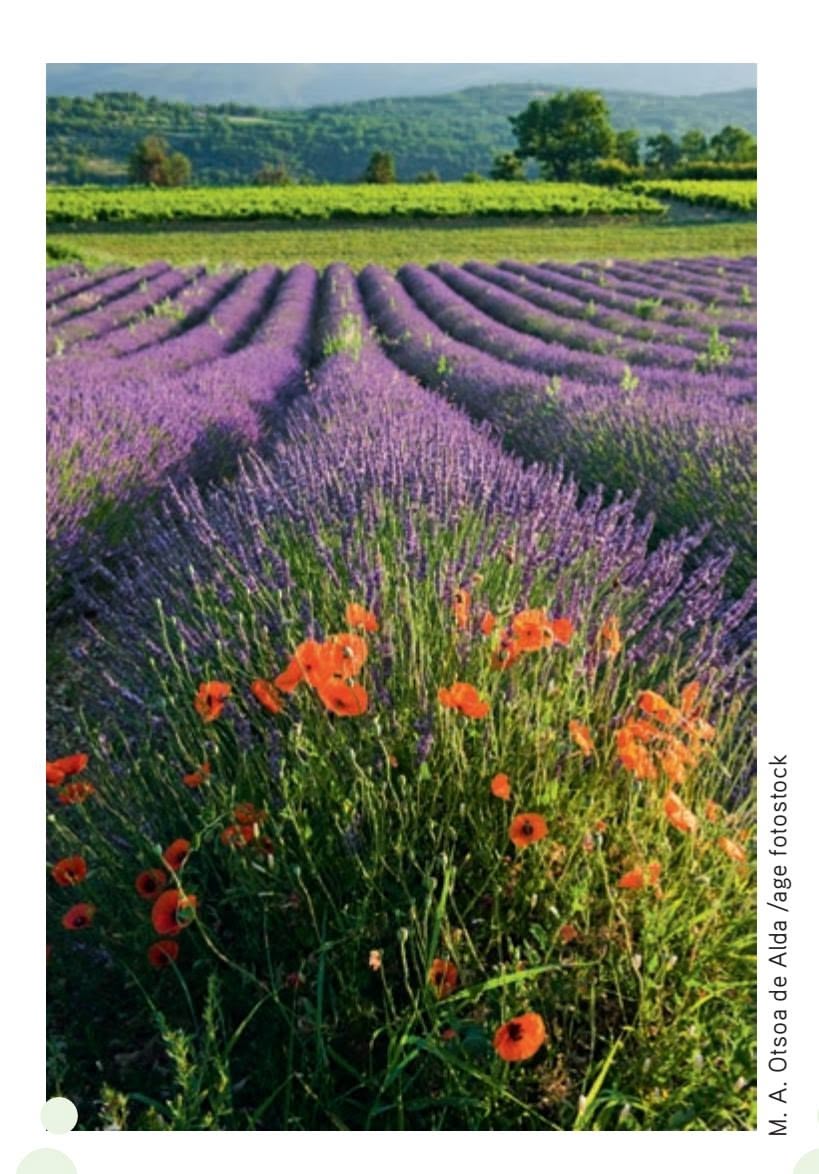

**The Roots of Collectivistic Culture?** Even within a given society, people's cultural values may vary. Thomas Talhem and his colleagues (2014) found that Chinese from northern China, where wheat is traditionally grown, are more individualistic than Chinese from southern China, where rice is grown, despite sharing the same ethnic, educational, and socioeconomic background. The explanation? As this photo of villagers in southwest China harvesting rice shows, rice farming requires an extraordinary level of cooperation and coordination among villagers, characteristics that are highly valued in collectivistic cultures. In contrast, wheat farmers can succeed without help from their neighbors.

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 12 11/20/15 11:58 AM

Contemporary Psychology 13

psychologists began studying the diversity of human behavior in different cultural settings and countries (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011; P. Smith, 2010). In the process, psychologists discovered that some well-established psychological findings were not as universal as they had thought.

For example, one well-established psychological finding was that people exert more effort on a task when working alone than

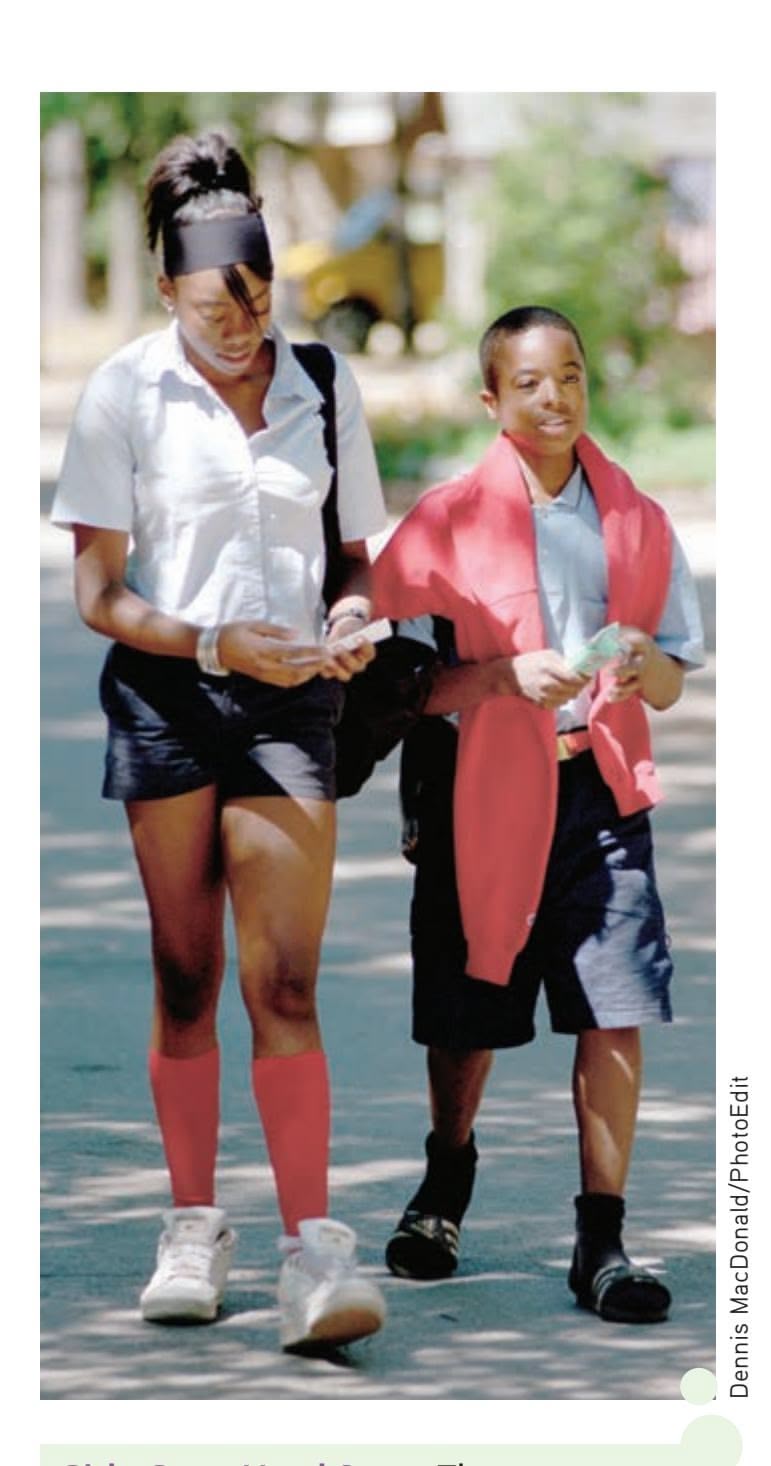

**Cultural Differences in Everyday**

**Behavior** Our everyday behavior reflects *cultural norms*—unspoken standards of social behavior. For example, imagine the behavior of commuters on a subway platform in any large U.S. city. Contrast that behavior with that of commuters in Japan. White-gloved conductors obligingly "assist" passengers in boarding by shoving them in from behind, cramming as many people into the subway car as possible.

when working as part of a group, a phenomenon called *social loafing.* First demonstrated in the 1970s, social loafing was a consistent finding in several psychological studies conducted with American and European subjects. But when similar studies were conducted with Chinese participants, the opposite was found to be true (Hong & others, 2008). Chinese participants worked harder on a task when they were part of a group than when they were working alone, a phenomenon called *social striving*.

Today, psychologists are keenly attuned to the influence of cultural factors on behavior (Heine, 2010; Henrich & others, 2010). Although many psychological processes *are* shared by all humans, it's important to keep in mind that there are cultural variations in behavior. Thus, we have included Culture and Human Behavior boxes throughout this textbook to help sensitize you to the influence of culture on behavior—including your own. We describe cross-cultural psychology in more detail in the Culture and Human Behavior box on page 12.

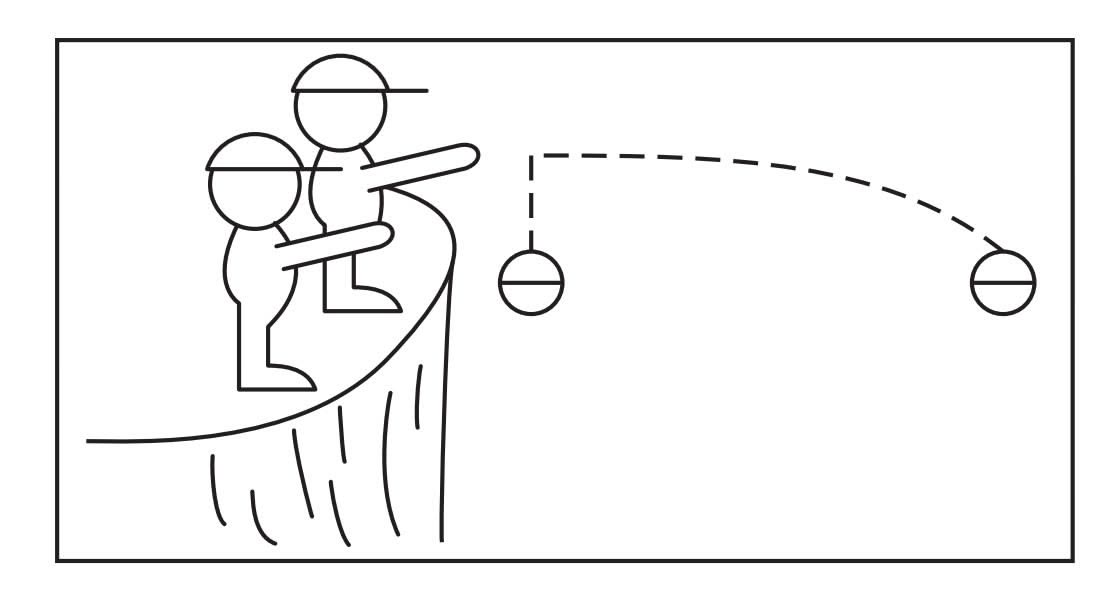

## THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

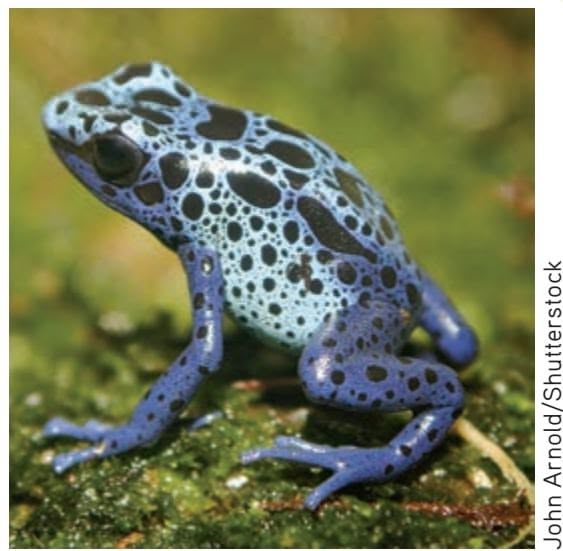

**Evolutionary psychology** refers to the application of the principles of evolution to explain psychological processes and phenomena (Buss, 2009, 2011b). The *evolutionary perspective* reflects a renewed interest in the work of English naturalist Charles Darwin. As noted previously, Darwin's (1859) first book on evolution, *On the Origin of Species,* played an influential role in the thinking of many early psychologists.

The theory of evolution proposes that the individual members of a species compete for survival. Because of inherited differences, some members of a species are better adapted to their environment than are others. Organisms that inherit characteristics that increase their chances of survival in their particular habitat are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics to their offspring. But individuals that inherit less useful characteristics are less likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics. This process reflects the principle of *natural selection*: The most adaptive characteristics are "selected" and perpetuated in the next generation.

Psychologists who take the evolutionary perspective assume that psychological processes are also subject to the principle of natural selection. As David Buss (2008) writes, "An evolved psychological mechanism exists in the form that it does because it solved a specific problem of survival or reproduction recurrently over evolutionary history." That is, psychological processes that helped individuals adapt to their environments also helped them survive, reproduce, and pass those abilities **culture** The attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to another.

**cross-cultural psychology** Branch of psychology that studies the effects of culture on behavior and mental processes.

**ethnocentrism** The belief that one's own culture or ethnic group is superior to all others and the related tendency to use one's own culture as a standard by which to judge other cultures.

**individualistic cultures** Cultures that emphasize the needs and goals of the individual over the needs and goals of the group.

**collectivistic cultures** Cultures that emphasize the needs and goals of the group over the needs and goals of the individual.

**evolutionary psychology** The application of principles of evolution, including natural selection, to explain psychological processes and phenomena.

14 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

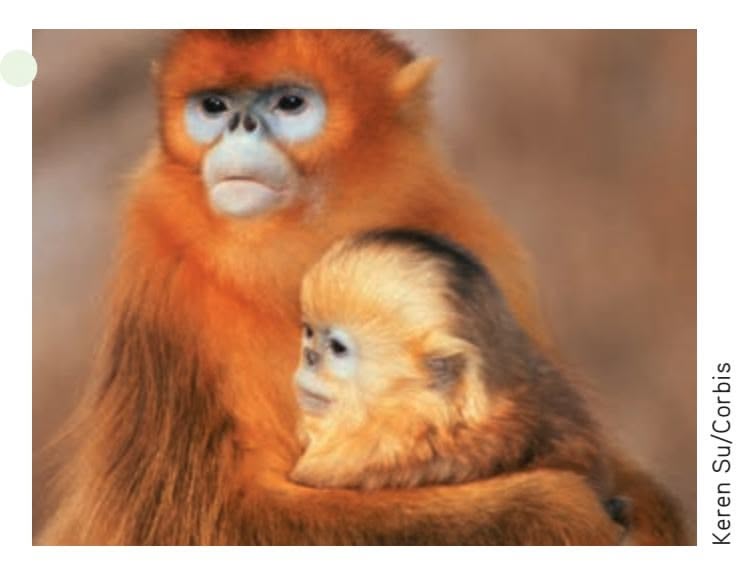

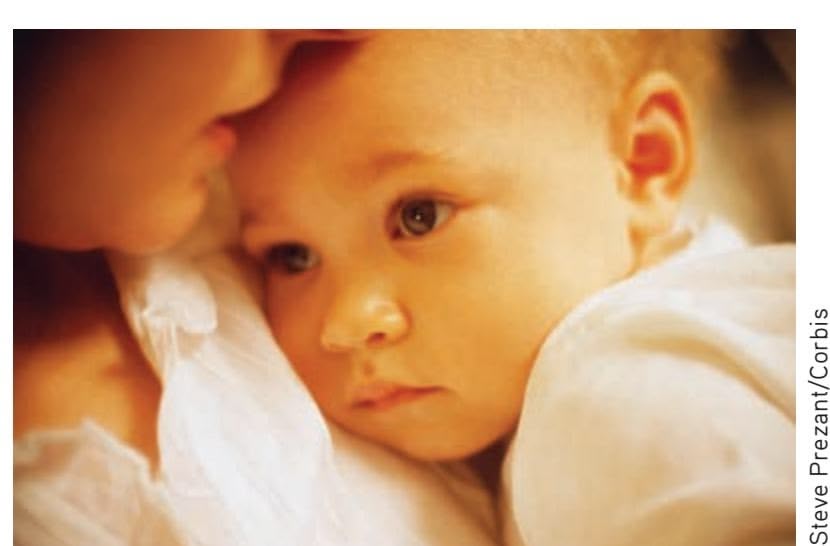

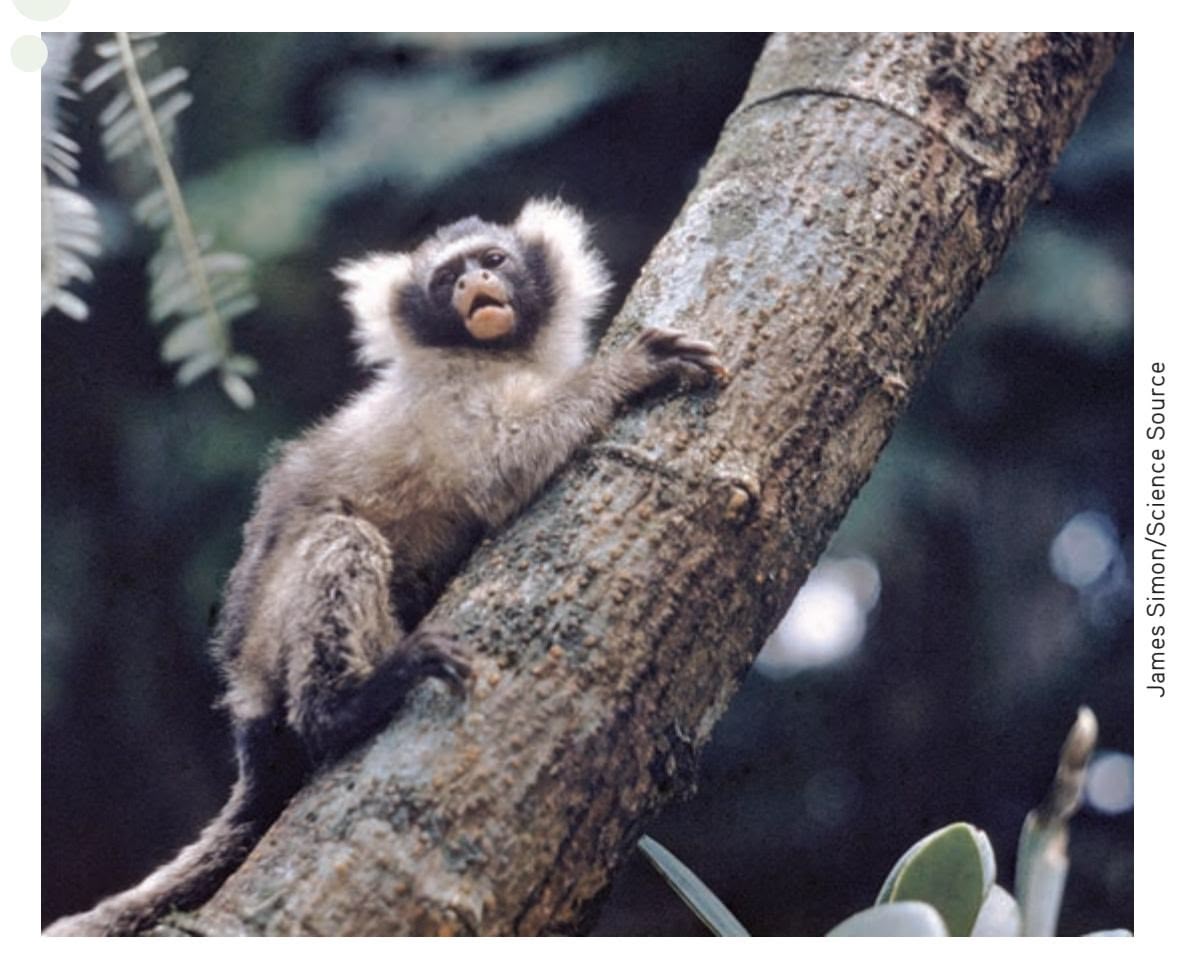

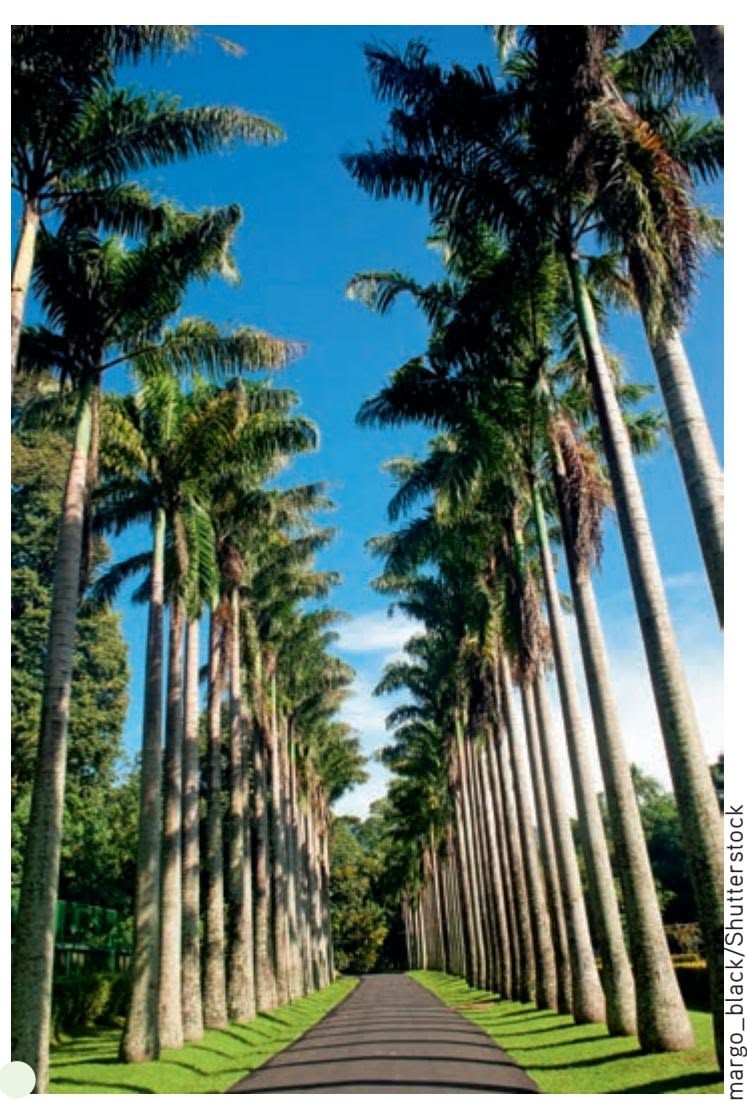

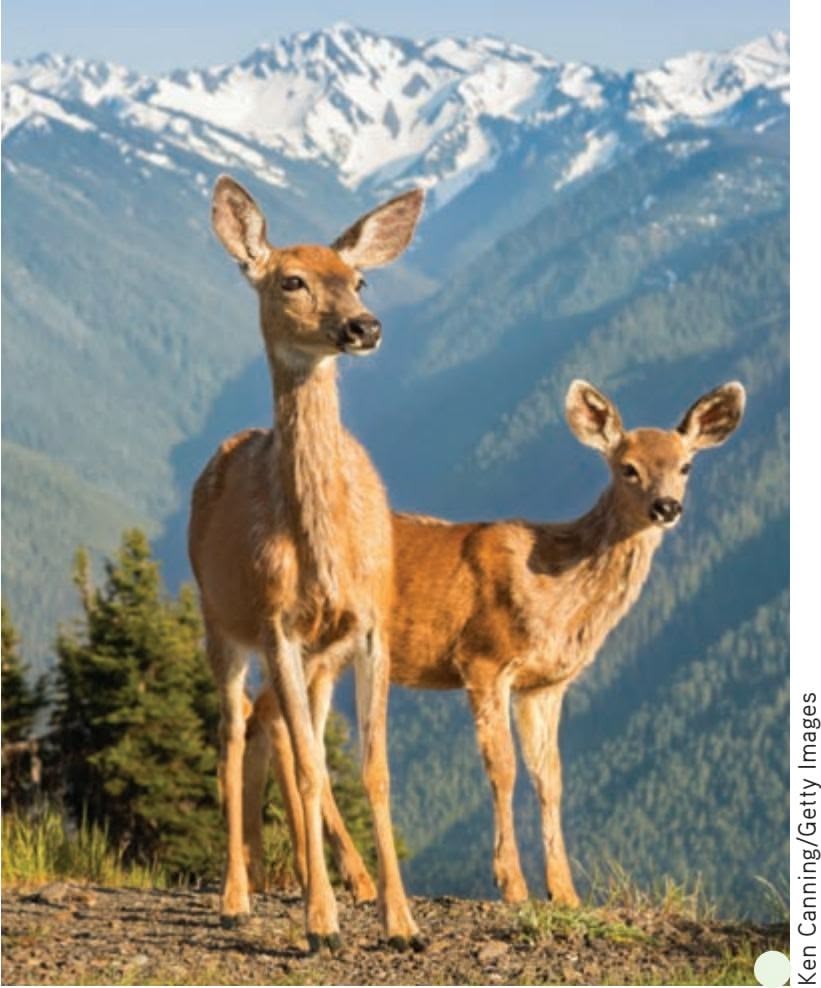

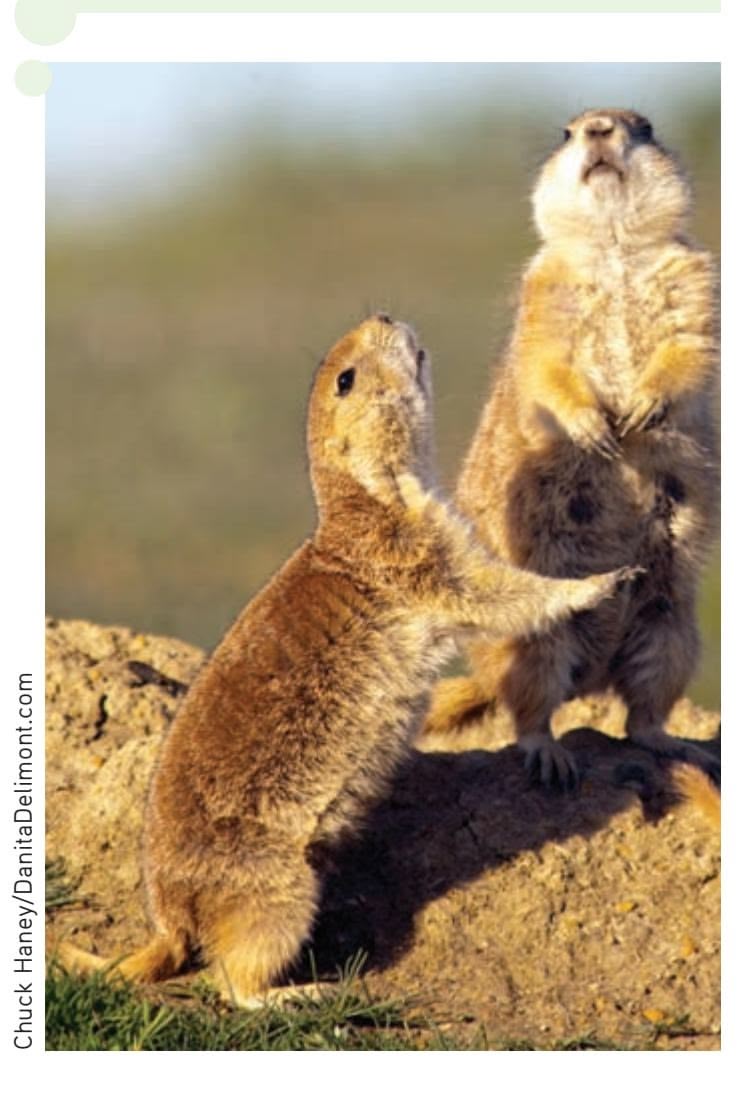

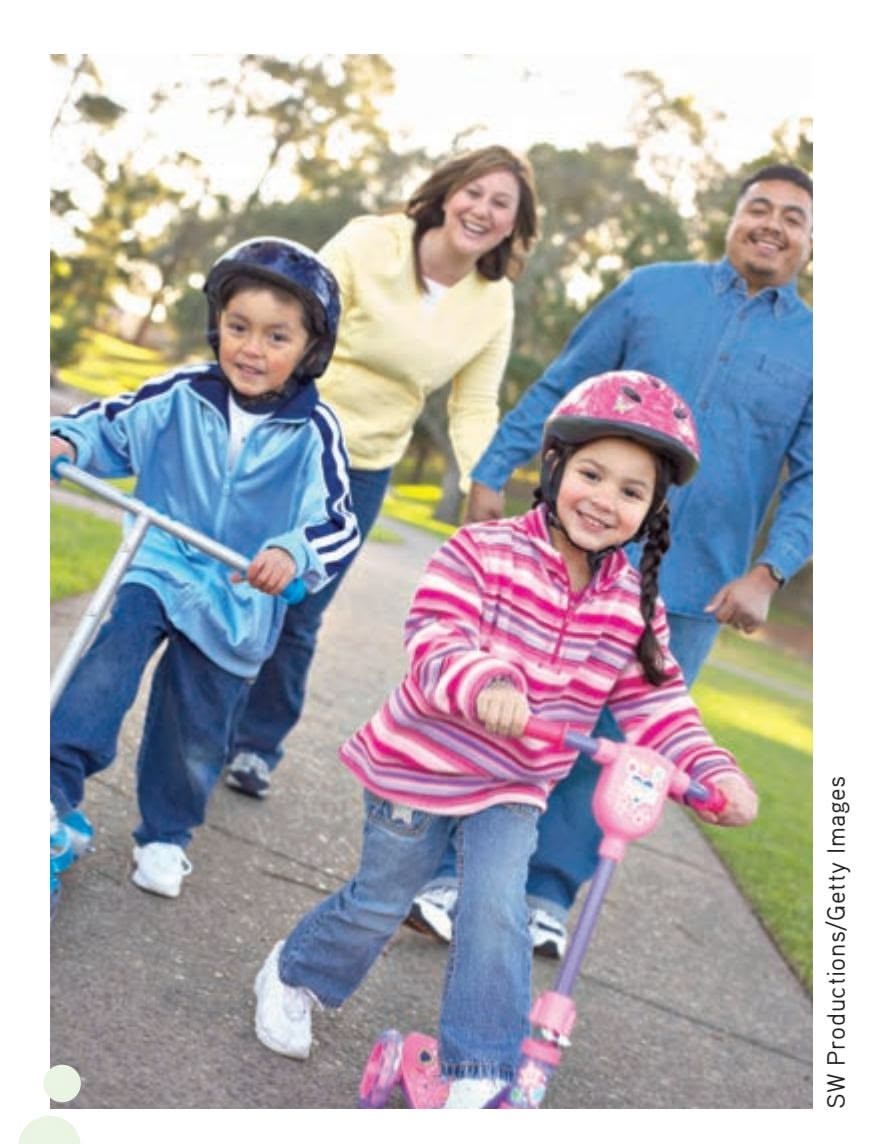

**The Evolutionary Perspective** The evolutionary perspective analyzes behavior in terms of how it increases a species' chances to survive and reproduce. Comparing behaviors across species can often lead to new insights about the adaptive function of a particular behavior. For example, close bonds with caregivers are essential to the primate infant's survival—whether that infant is a golden monkey at a wildlife preserve in northern China or a human infant at a family picnic in Norway. As you'll see in later chapters, the evolutionary perspective has been applied to many different areas of psychology, including human relationships, eating behaviors, and emotional responses (Confer & others, 2010; Scott-Phillips & others, 2011).

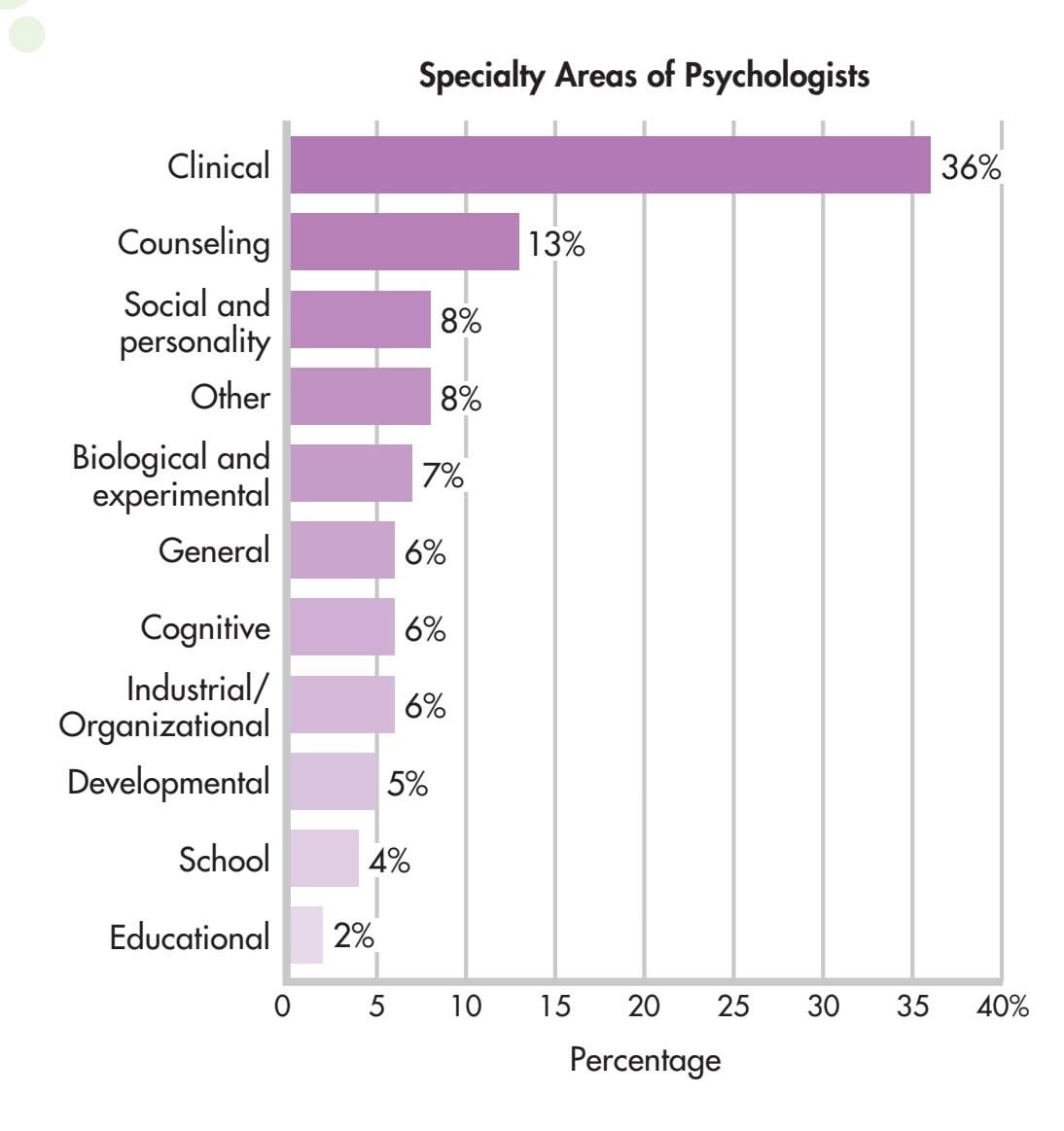

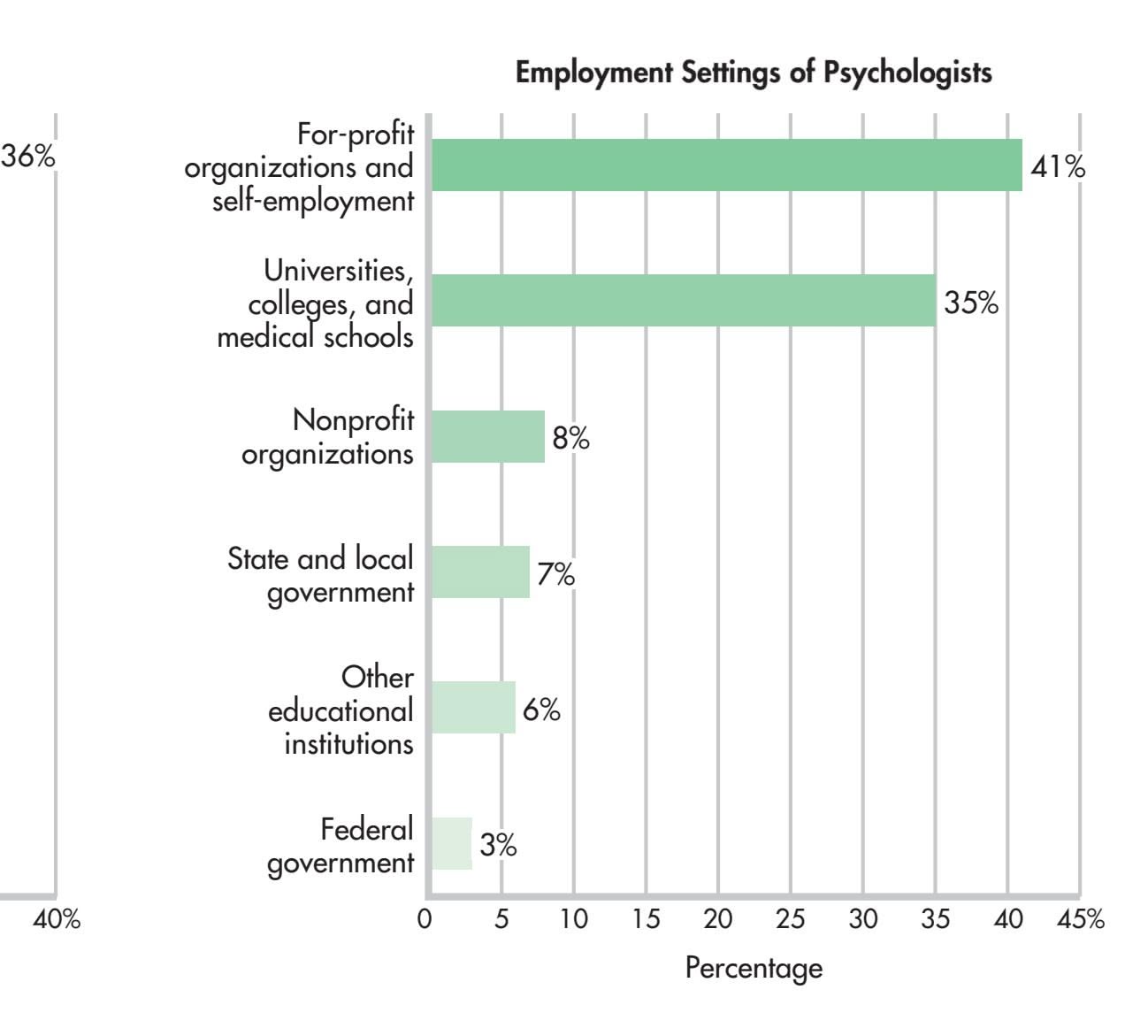

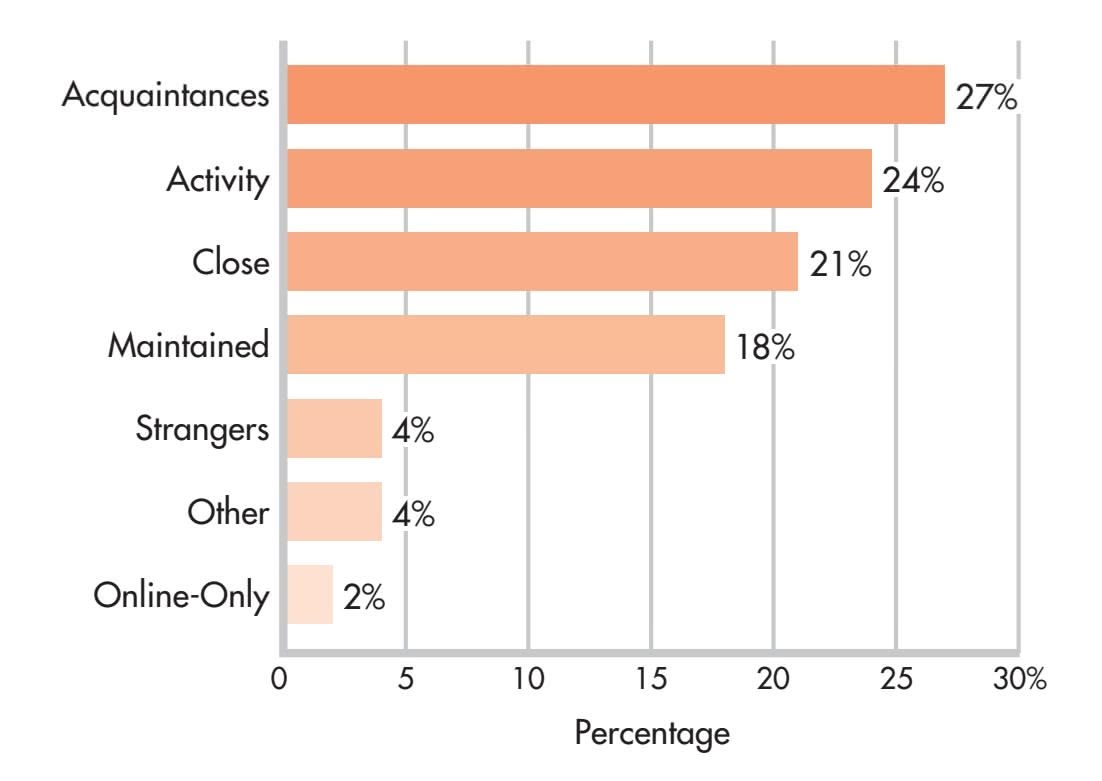

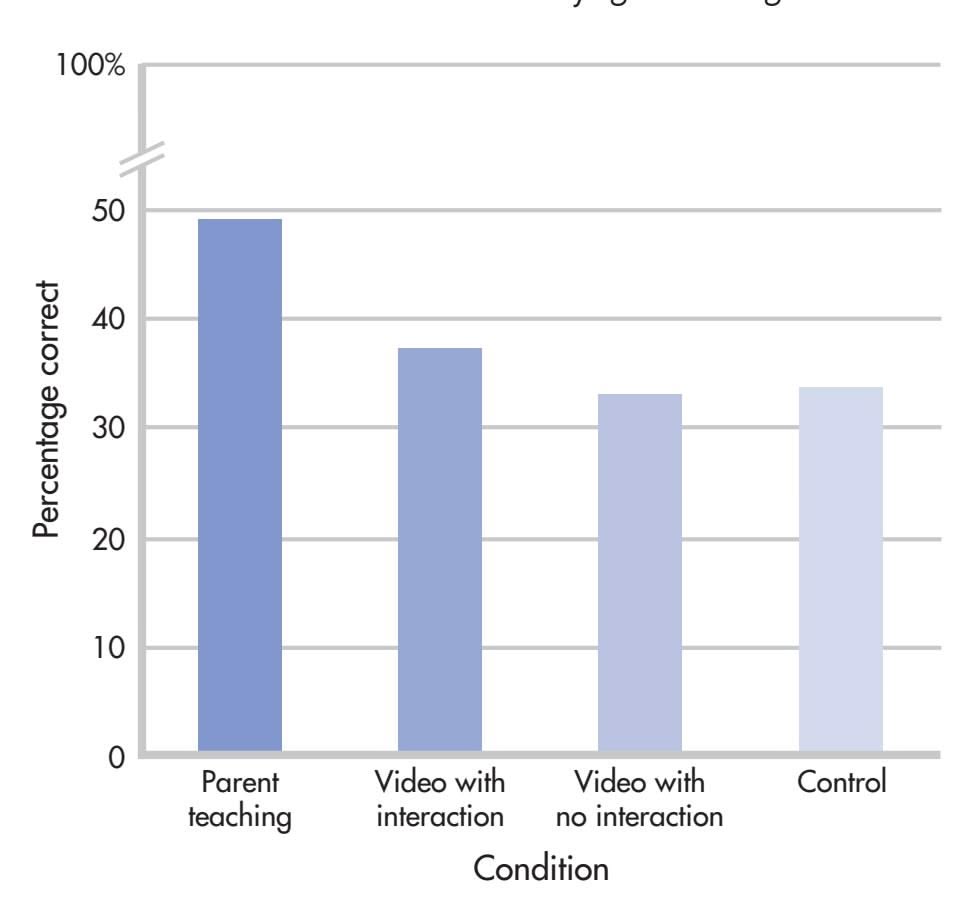

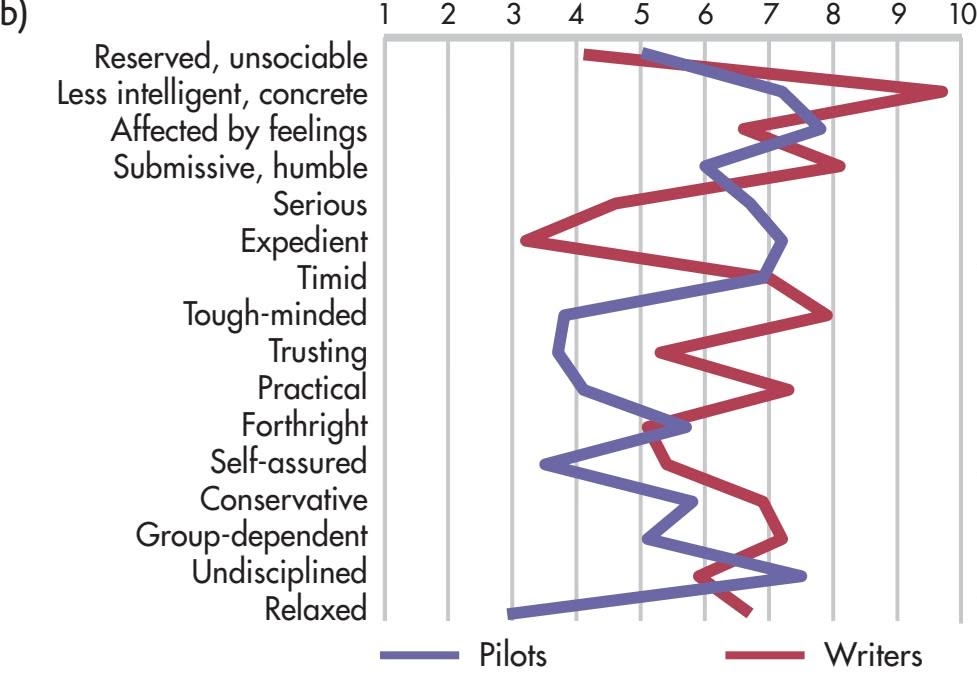

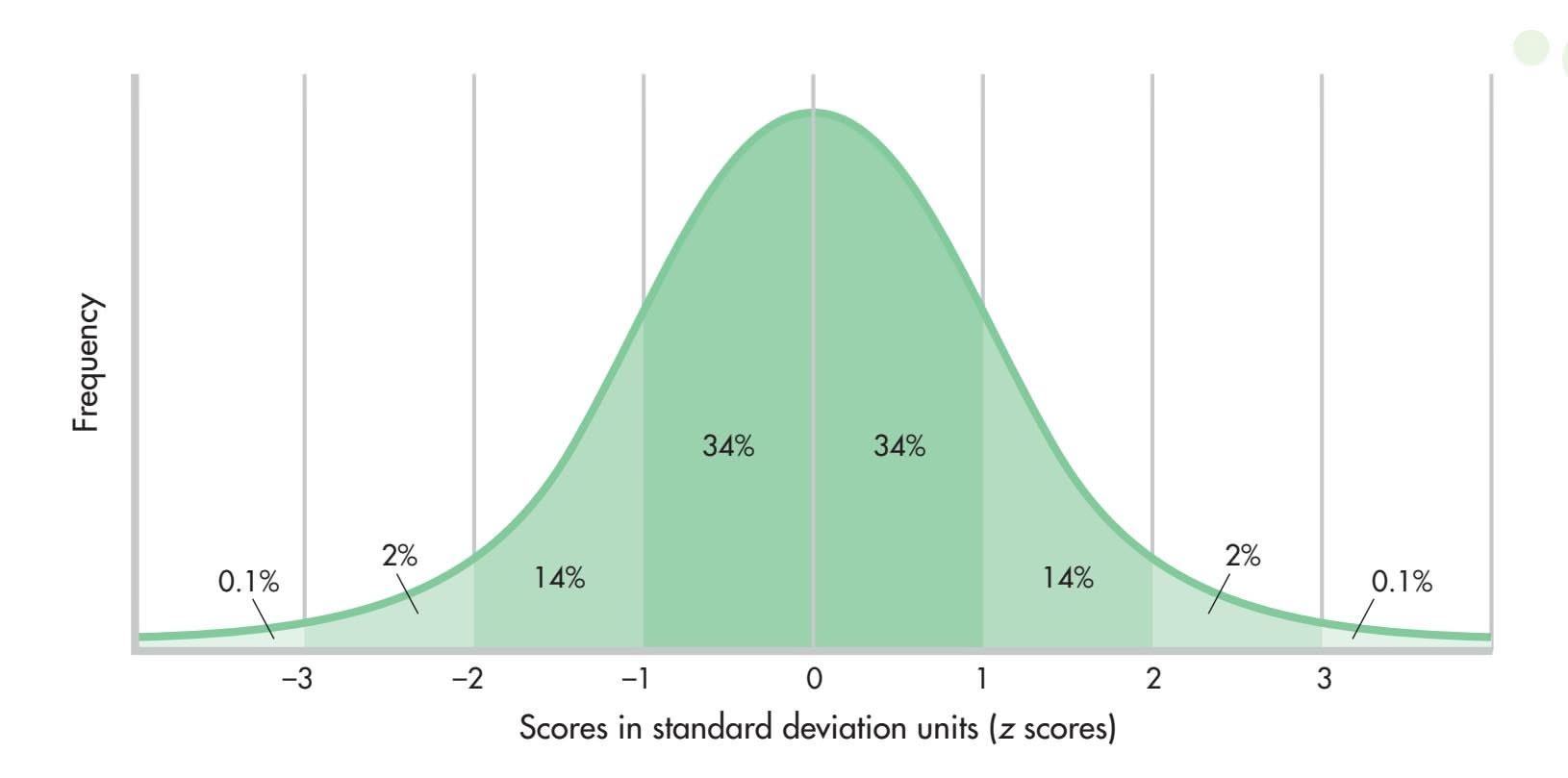

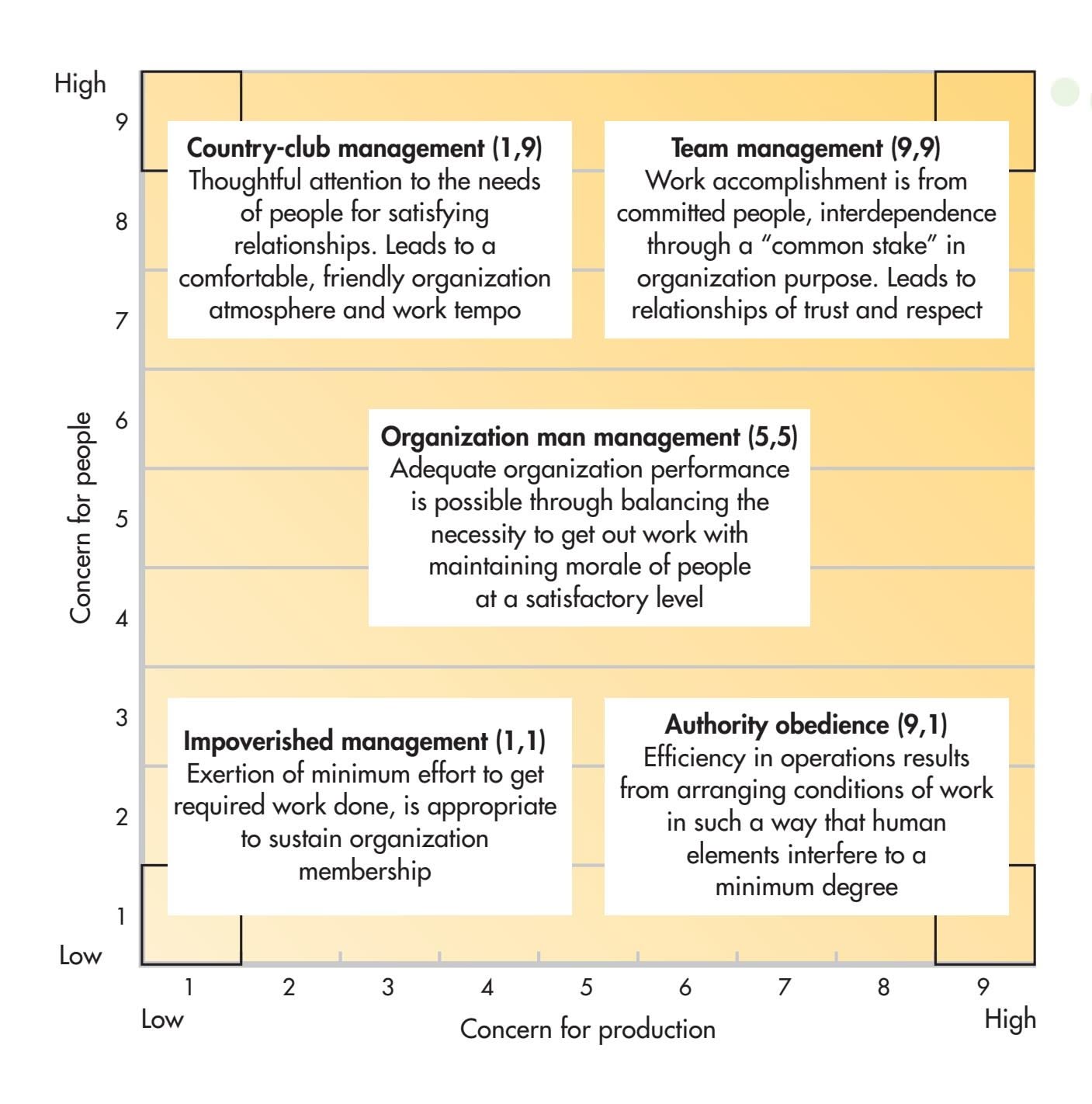

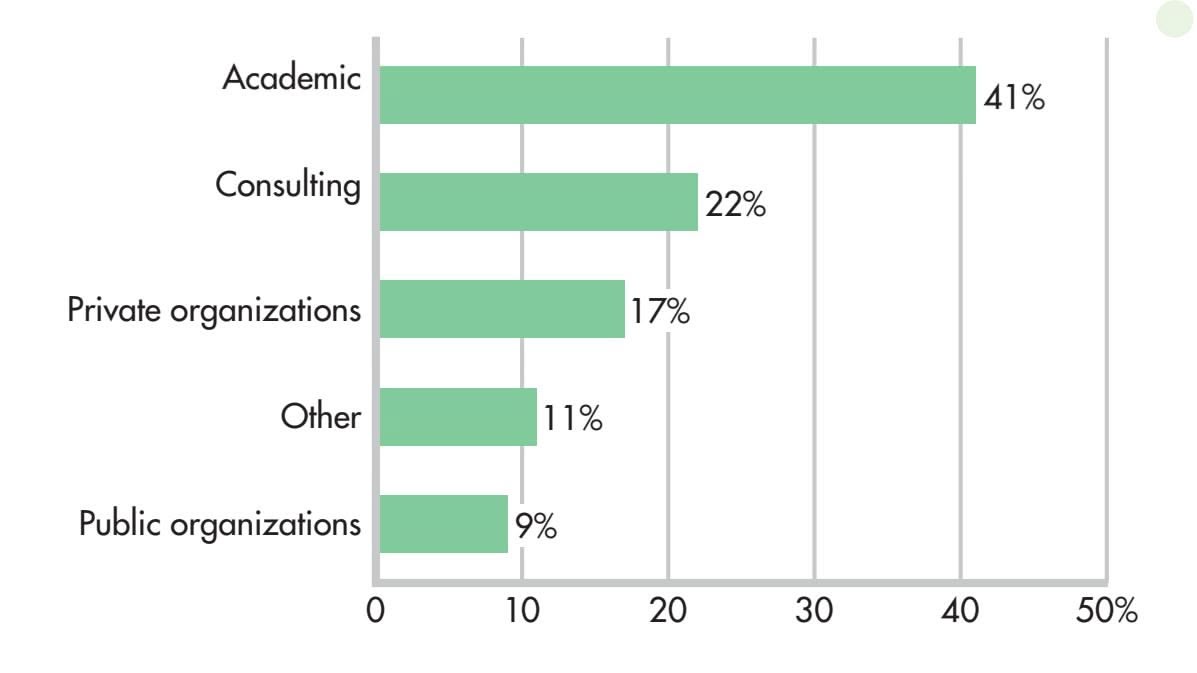

**FIGurE 1.1** Specialty Areas and Employment Settings The graph on the left shows the specialty areas of individuals who recently received their doctorates in psychology. The category "Other" includes such specialty areas as health psychology, forensic psychology, and sports psychology. The right graph shows psychologists' primary places of employment.

> Source: Data from Finno & others (2006); NSF/NIH/USED/USDA/NEH/NASA, 2009 Survey of Earned Doctorates.

on to their offspring (Confer & others, 2010). However, as you'll see in later chapters, some of those processes may not necessarily be adaptive in our modern world [\(Loewenstein, 2010; Tooby & Cosmides,](#page--1-0) 2008).

## Specialty Areas in Psychology

Many people think that psychologists primarily diagnose and treat people with psychological problems or disorders. In fact, psychologists who specialize in *clinical psychology* are trained in the diagnosis, treatment, causes, and prevention of psychological disorders, leading to a doctorate in clinical psychology.

In contrast, **psychiatry** is a medical specialty. A psychiatrist has earned a medical degree, either an M.D. or D.O., followed by several years of specialized training in the treatment of mental disorders. As physicians, psychiatrists can hospitalize people, order biomedical therapies such as *electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),* and prescribe medications. Clinical psychologists are not medical doctors and cannot order medical treatments. However, a few states have passed legislation allowing clinical psychologists to prescribe medications after specialized training (Riding-Malon & Werth, 2014).

As you'll learn, contemporary psychology is a very diverse discipline that ranges far beyond the treatment of psychological problems. This diversity is reflected in Figure 1.1, which shows the range of specialty areas and employment settings for

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 14 11/20/15 11:58 AM

The Scientific Method 15

### **tABLE 1.1**

## Major Specialties in Psychology

| Specialty | Major Focus |

|-----------------------------------------|--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Biological psychology | Relationship between psychological processes and the body's physi

cal systems; neuroscience refers specifically to the study of the

brain and the rest of the nervous system. |

| Clinical psychology | Causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of psychological

disorders. |

| Cognitive psychology | Mental processes, including reasoning and thinking, problem

solving, memory, perception, mental imagery, and language. |

| Counseling psychology | Helping people adjust, adapt, and cope with personal and interper

sonal challenges; improving well-being, alleviating distress and mal

adjustment, and resolving crises. |

| Developmental psychology | Physical, social, and psychological changes that occur at different

ages and stages of the life span. |

| Educational psychology | Applying psychological principles and theories to methods of

learning. |

| Experimental psychology | Basic psychological processes, including sensation and perception,

and principles of learning, emotion, and motivation. |

| Health psychology | Psychological factors in the development, prevention, and treat

ment of illness; stress and coping; promoting health-enhancing

behaviors. |

| Industrial/Organizational

psychology | The relationship between people and work. |

| Personality psychology | The nature of human personality, including the uniqueness of each

person, traits, and individual differences. |

| Social psychology | How an individual's thoughts, feelings, and behavior are affected by

social environments and the presence of other people. |

| School psychology | Applying psychological principles and findings in primary and

secondary schools. |

| Applied psychology | Applying the findings of basic psychology to diverse areas; examples

include sports psychology, media psychology, forensic psychology,

rehabilitation psychology, and military psychology. |

psychologists. Table 1.1 provides a brief overview of psychology's most important specialty areas.

❯ [Test your understanding of](#page--1-0) **Contemporary Psychology** with .

# The Scientific Method

#### KEY THEME

The scientific method is a set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that guides all scientists, including psychologists, in conducting research.

#### KEY QUESTIONS

- ❯ What assumptions and attitudes are held by psychologists?

- ❯ What characterizes each step of the scientific method?

- ❯ How does a hypothesis differ from a theory?

Whatever their approach or specialty, psychologists who do research are scientists. And, like other scientists, they rely on the scientific method to guide their research. The **scientific method** refers to a set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that **psychiatry** Medical specialty area focused on the diagnosis, treatment, causes, and prevention of mental and behavioral disorders.

**scientific method** A set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that guide researchers in creating questions to investigate, in generating evidence, and in drawing conclusions.

Hockenbury\_7e\_CH01\_Printer.indd 15 11/20/15 11:58 AM

16 CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Research Methods

**empirical evidence** Verifiable evidence that is based upon objective observation, measurement, and/or experimentation.

**hypothesis** (high-POTH-uh-sis) A tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables; a testable prediction or question.

**variable** A factor that can vary, or change, in ways that can be observed, measured, and verified.

**operational definition** A precise description of how the variables in a study will be manipulated or measured.

guide researchers in creating questions to investigate, in generating evidence, and in drawing conclusions.