SPECIAL EDITION

Selections from the Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations

# Title Page

Copyright

# Foreword

# Table of Contents: Part 1

## Neuroanatomy

# Table of Contents: Part 2

## Neurophysiology

# Installing Adobe Acrobat

## Reader 5.0

Illustrations by

Frank H. Netter, MD

John A. Craig, MD

James Perkins, MS, MFA

Text by

John T. Hansen, PhD

Bruce M. Koeppen, MD, PhD

# Atlas of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology

Selections from the Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations

Illustrations by

Frank H. Netter, MD John A. Craig, MD James Perkins, MS, MFA

Text by John T. Hansen, PhD Bruce M. Koeppen, MD, PhD

## Atlas of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology Selections from the Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations

### Copyright 2002 Icon Custom Communications. All rights reserved.

The contents of this book may not be reproduced in any form without written authorization from Icon Custom Communications. Requests for permission should be addressed to Permissions Department, Icon Custom Communications, 295 North St., Teterboro NJ 07608, or can be made at www. Netterart.com.

## NOTICE

Every effort has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented. Neither the publisher nor the authors can be held responsible for errors or for any consequences arising from the use of the information contained herein, and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the contents of the publication.

Printed in U.S.A.

# Foreword

## Frank Netter: The Physician, The Artist, The Art

This selection of the art of Dr. Frank H. Netter on neuroanatomy and neurophysiology is drawn from the *Atlas of Human Anatomy* and *Netter's Atlas of Human Physiology.* Viewing these pictures again prompts reflection on Dr. Netter's work and his roles as physician and artist.

Frank H. Netter was born in 1906 in New York City. He pursued his artistic muse at the Sorbonne, the Art Student's League, and the National Academy of Design before entering medical school at New York University, where he received his M.D. degree in 1931. During his student years, Dr. Netter's notebook sketches attracted the attention of the medical faculty and other physicians, allowing him to augment his income by illustrating articles and textbooks. He continued illustrating as a sideline after establishing a surgical practice in 1933, but ultimately opted to give up his practice in favor of a full-time commitment to art. After service in the United States Army during the Second World War, Dr. Netter began his long collaboration with the CIBA Pharmaceutical Company (now Novartis Pharmaceuticals). This 45-year partnership resulted in the production of the extraordinary collection of medical art so familiar to physicians and other medical professionals worldwide.

When Dr. Netter's work is discussed, attention is focused primarily on Netter the artist and only secondarily on Netter the physician. As a student of Dr. Netter's work for more than forty years, I can say that the true strength of a Netter illustration was always established well before brush was laid to paper. In that respect each plate is more of an intellectual than an artistic or aesthetic exercise. It is easy to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of Dr. Netter's work, but to overlook its intellectual qualities is to miss the real strength and intent of the art. This intellectual process requires thorough understanding of the topic, as Dr. Netter wrote: "Strange as it may seem, the hardest part of making a medical picture is not the drawing at all. It is the planning, the conception, the determination of point of view and the approach which will best clarify the subject which takes the most effort."

Years before the inception of "the integrated curriculum," Netter the physician realized that a good medical illustration can include clinical information and physiologic functions as well as anatomy. In pursuit of this principle Dr. Netter often integrates pertinent basic and clinical science elements in his anatomic interpretations. Although he was chided for this heresy by a prominent European anatomy professor, many generations of students training to be physicians rather than anatomists have appreciated Dr. Netter's concept.

The integration of physiology and clinical medicine with anatomy has led Dr. Netter to another, more subtle, choice in his art. Many texts and atlases published during the period of Dr. Netter's career depict anatomy clearly based on cadaver specimens with renderings of shrunken and shriveled tissues and organs. Netter the physician chose to render "live" versions of these structures—not shriveled, colorless, formaldehyde-soaked tissues, but plump, robust organs, glowing with color!

The value of Dr. Netter's approach is clearly demonstrated by the plates in this selection.

John A. Craig, MD Austin, Texas

This volume brings together two distinct but related aspects of the work of Frank H. Netter, MD, and associated artists. Netter is best known as the creator of the *Atlas of Human Anatomy*, a comprehensive textbook of gross anatomy that has become the standard atlas for students of the subject. But Netter's work included far more than anatomical art. In the pages of *Clinical Symposia*, a series of monographs published over a period of more than 50 years, and in *The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations*, this premier medical artist created superb illustrations of biological and physiological processes, disease pathology, clinical presentations, and medical procedures.

As a service to the medical community, Novartis Pharmaceuticals has commissioned this special edition of Netter's work, which includes his beautiful and instructive illustrations of nervous system anatomy as well as his depictions of neurophysiological concepts and functions. We hope that readers will find Dr. Netter's renderings of neurological form and function interesting and useful.

**Click any title below to link to that plate.**

# Part 1 Neuroanatomy

| Cerebrum—Medial Views

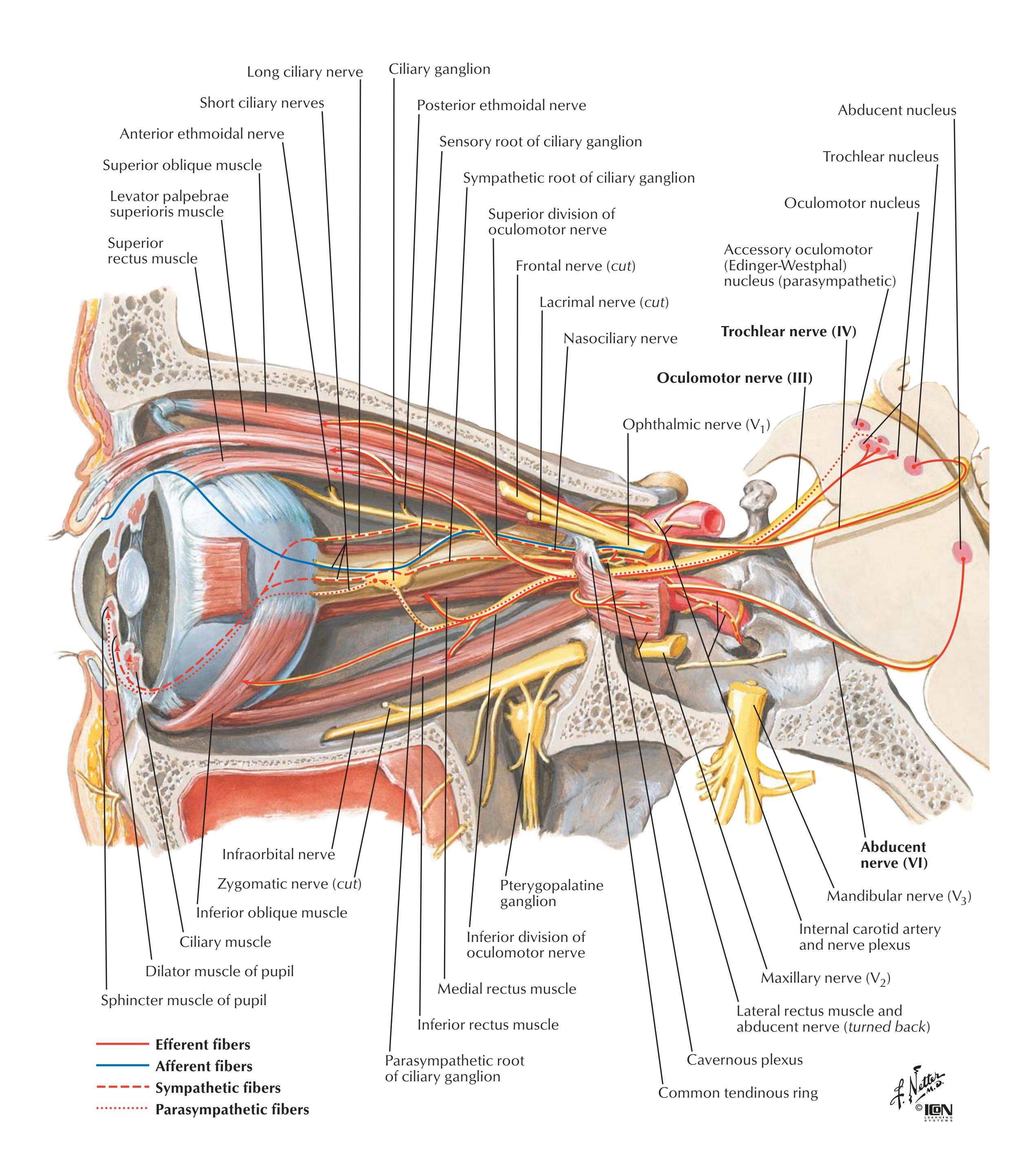

2 | Oculomotor (III), Trochlear (IV) | |

|---------------------------------------------------|-----------------------------------------------|--|

| Cerebrum—Inferior View 3 | and Abducent (VI) Nerves: Schema 27 | |

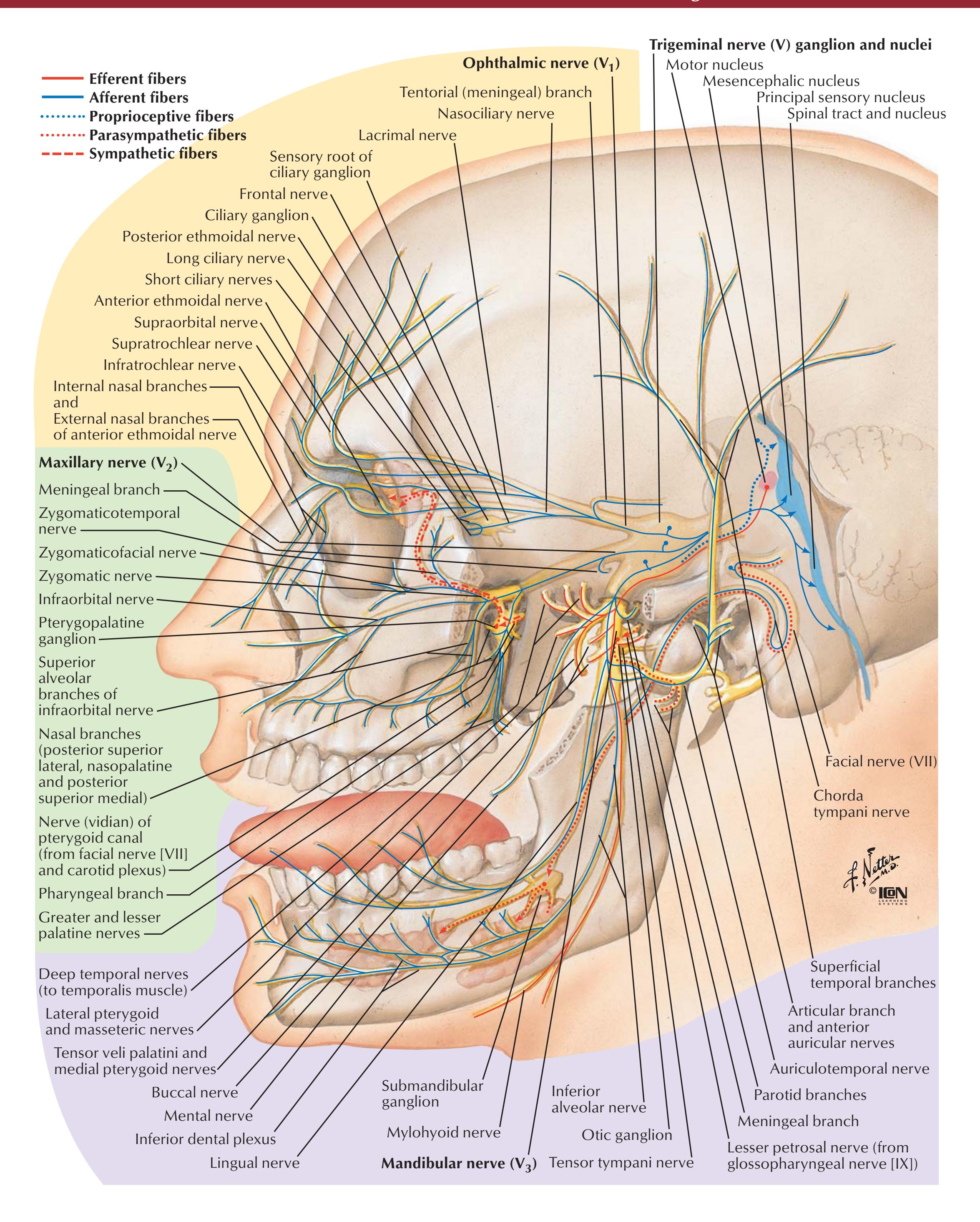

| Basal Nuclei (Ganglia) 4 | Trigeminal Nerve (V): Schema

28 | |

| Thalamus

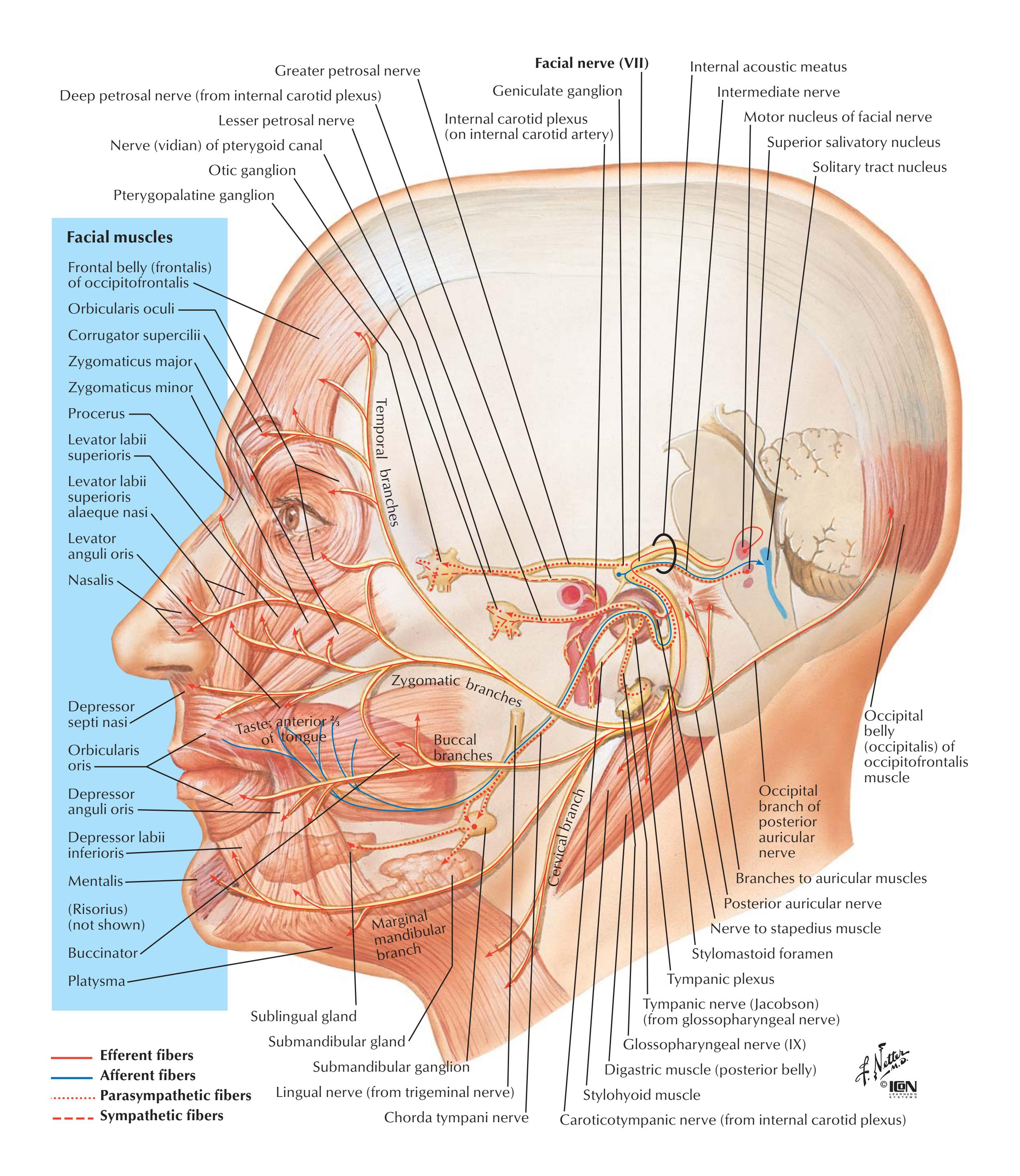

5 | Facial Nerve (VII): Schema

29 | |

| Cerebellum

6 | Vestibulocochlear Nerve (VIII): Schema 30 | |

| Brainstem 7 | Glossopharyngeal Nerve (IX): Schema

31 | |

| Fourth Ventricle and Cerebellum

8 | Vagus Nerve (X): Schema

32 | |

| Accessory Nerve (XI) 9 | Accessory Nerve (XI): Schema

33 | |

| Arteries to Brain and Meninges

10 | Hypoglossal Nerve (XII): Schema

34 | |

| Arteries to Brain: Schema

11 | Nerves of Heart

35 | |

| Arteries of Brain: Inferior Views

12 | Autonomic Nerves

and Ganglia of Abdomen 36 | |

| Cerebral Arterial Circle (Willis) 13 | Nerves of Stomach and Duodenum

37 | |

| Arteries of Brain: Frontal View and Section

14 | Nerves of Stomach | |

| Arteries of Brain: | and Duodenum (continued) 38 | |

| Lateral and Medial Views 15 | Nerves of Small Intestine

39 | |

| Arteries of Posterior Cranial Fossa

16 | Nerves of Large Intestine

40 | |

| Veins of Posterior Cranial Fossa

17 | Nerves of Kidneys, | |

| Deep Veins of Brain 18 | Ureters and Urinary Bladder

41 | |

| Subependymal Veins of Brain

19 | Nerves of Pelvic Viscera: Male

42 | |

| Hypothalamus and Hypophysis

20 | Nerves of Pelvic Viscera: Female

43 | |

| Arteries and Veins | Median Nerve

44 | |

| of Hypothalamus and Hypophysis

21 | Ulnar Nerve

45 | |

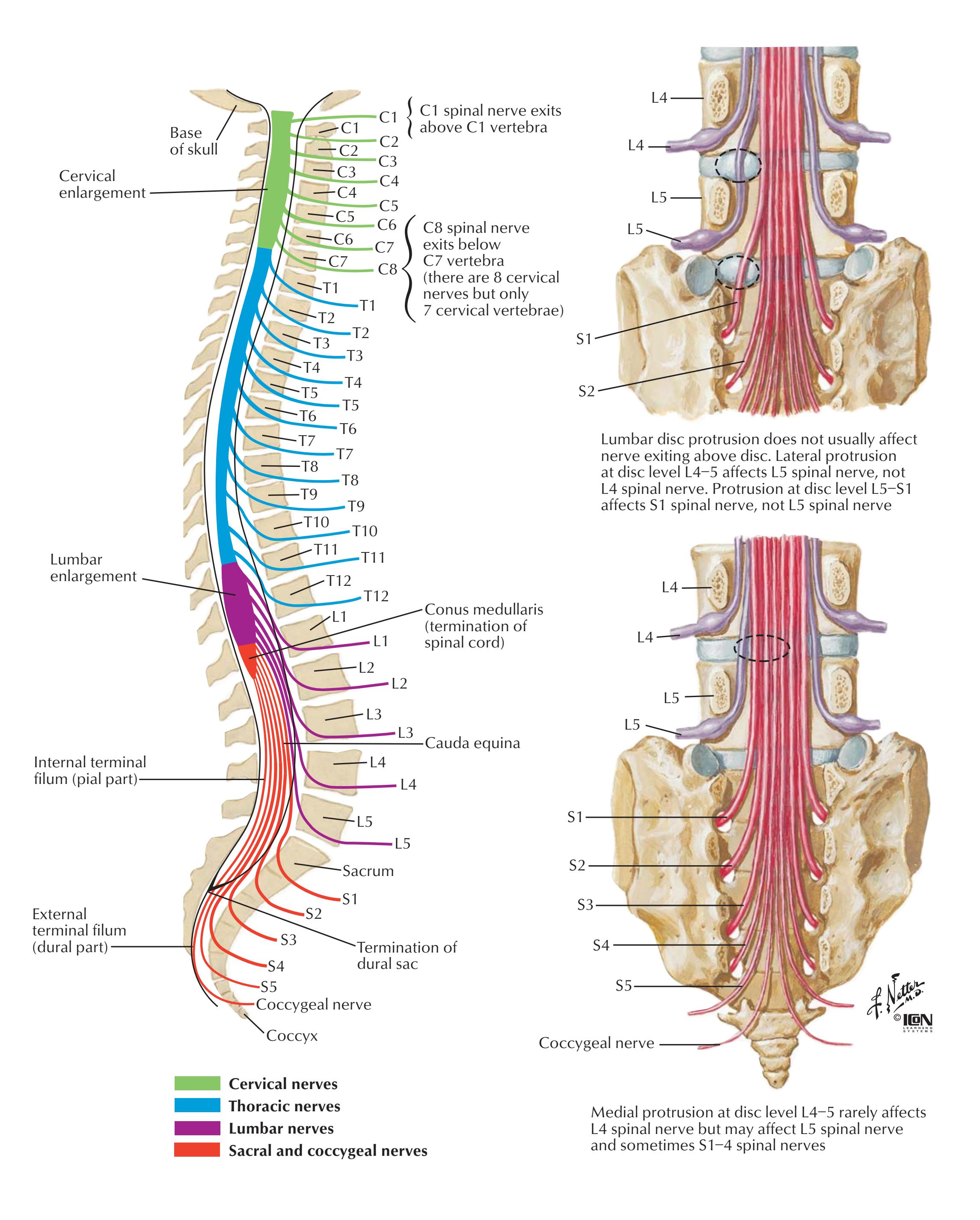

| Relation of Spinal Nerve Roots to Vertebrae

22 | Radial Nerve in Arm | |

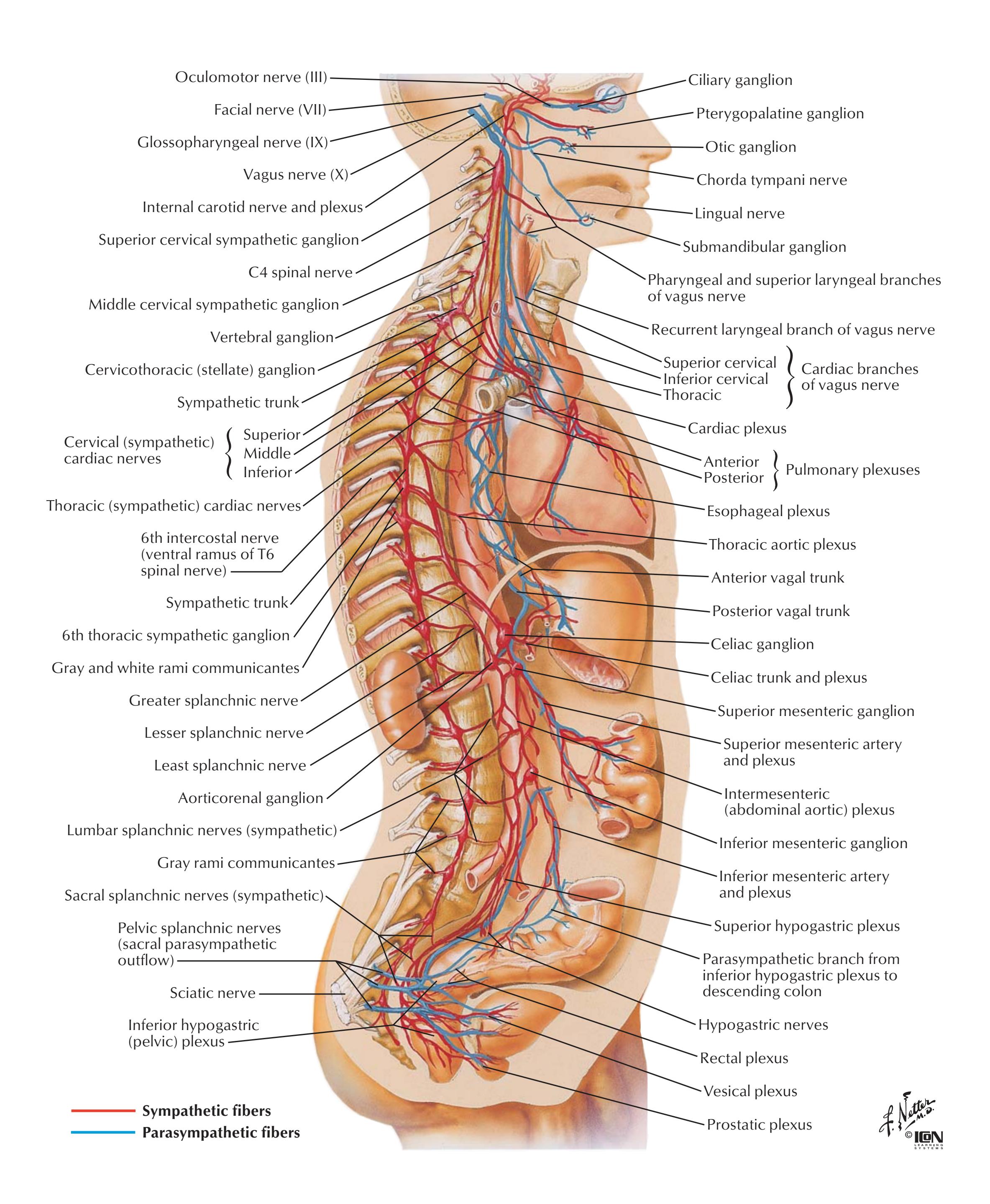

| Autonomic Nervous System: | and Nerves of Posterior Shoulder

46 | |

| General Topography 23 | Radial Nerve in Forearm

47 | |

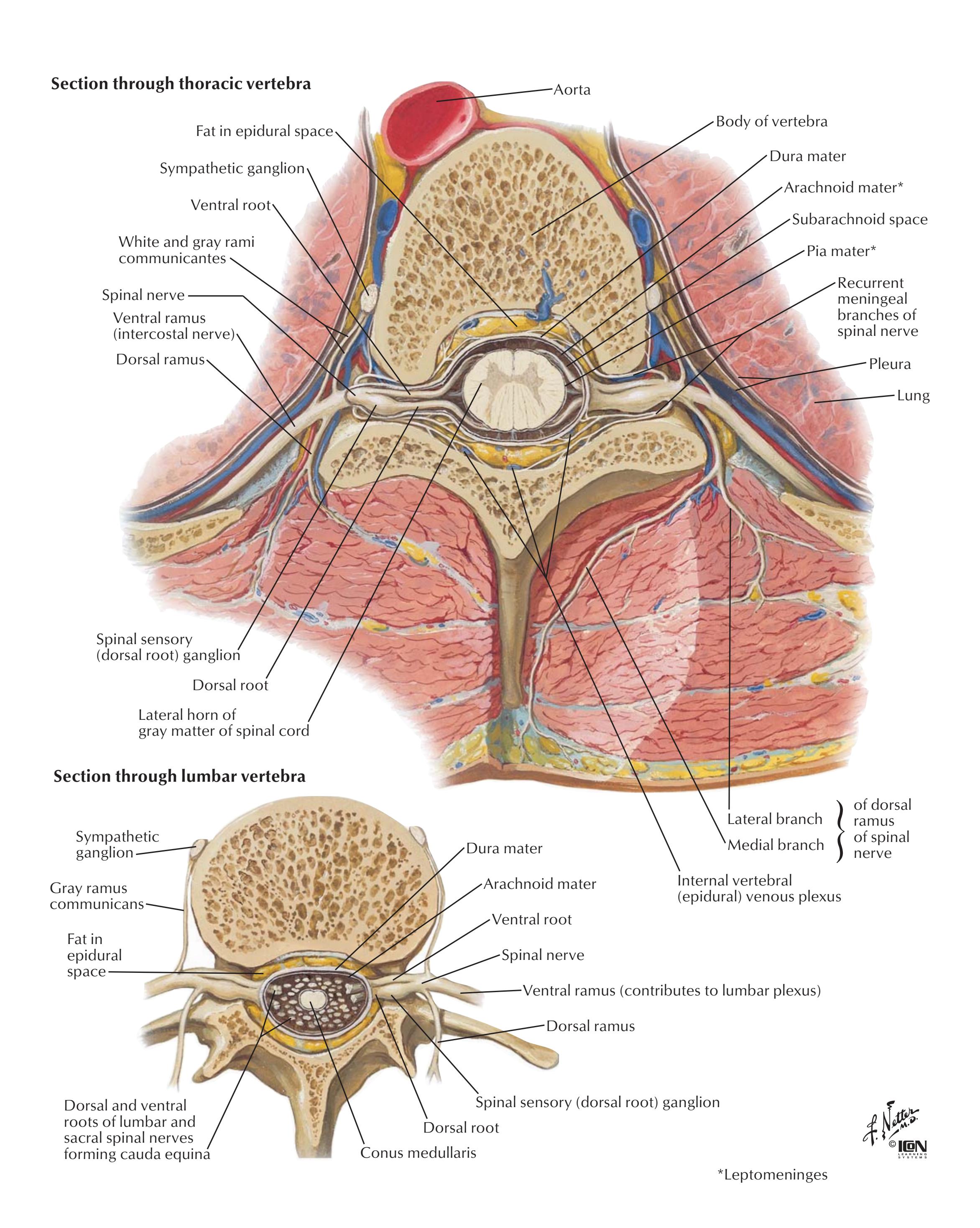

| Spinal Nerve Origin: Cross Sections 24 | Sciatic Nerve and Posterior | |

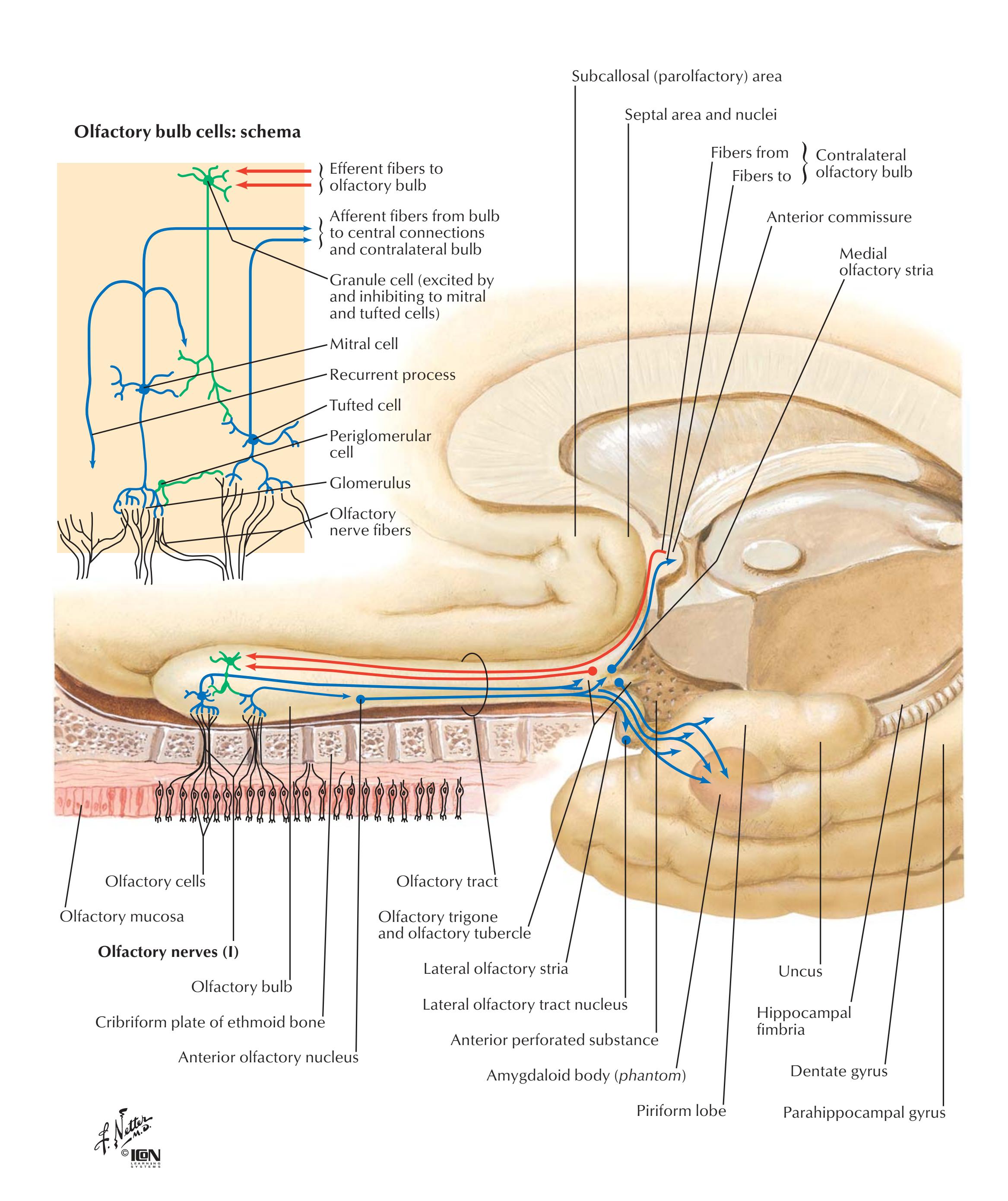

| Olfactory Nerve (I): Schema

25 | Cutaneous Nerve of Thigh

48 | |

| Optic Nerve (II) | Tibial Nerve

49 | |

| (Visual Pathway): Schema

26 | Common Fibular (Peroneal) Nerve 50 | |

**NEUROANATOMY Cerebrum: Medial Views**

**2**

**Cerebrum: Inferior View NEUROANATOMY**

**3**

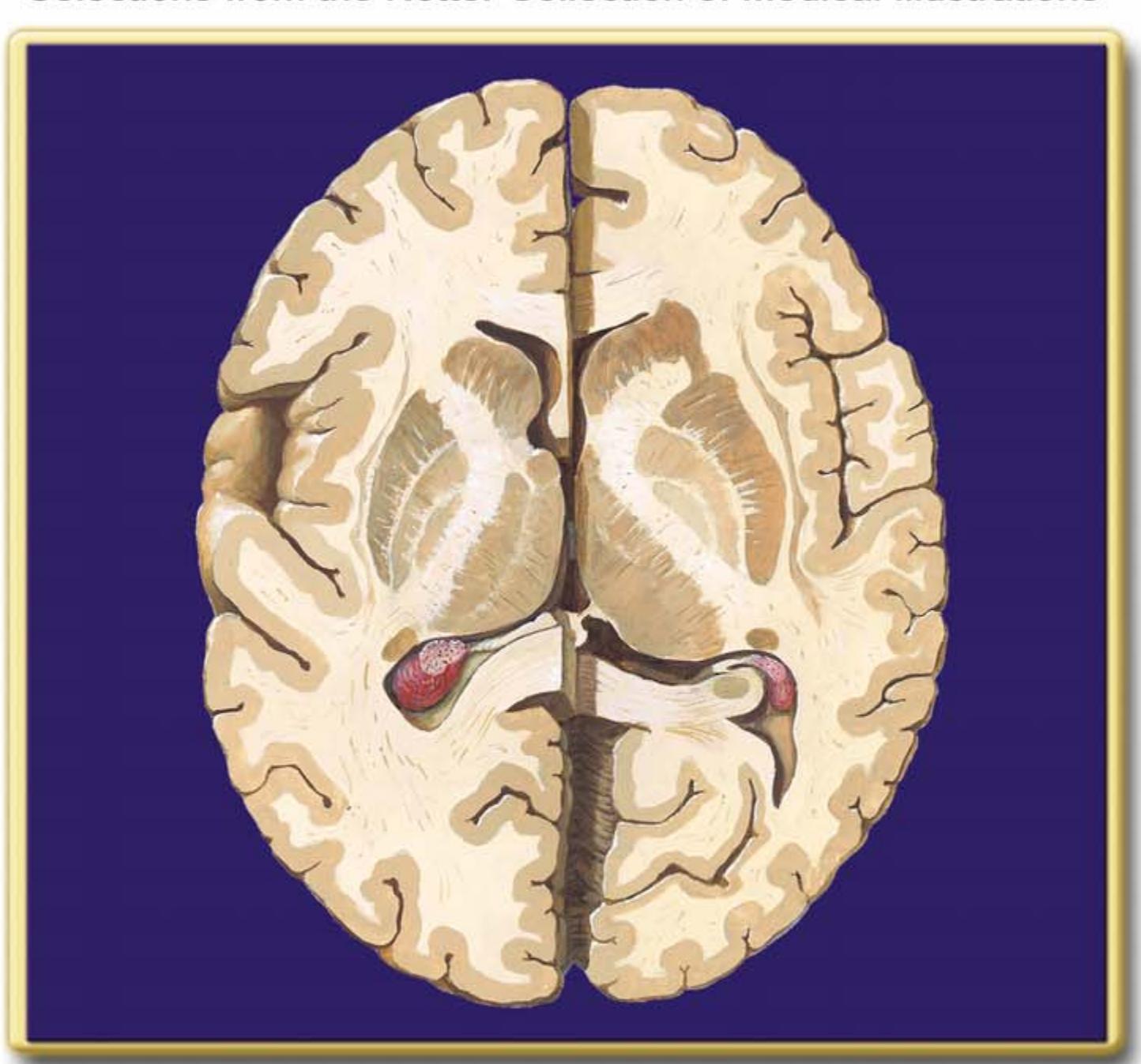

**NEUROANATOMY Basal Nuclei (Ganglia)**

**4**

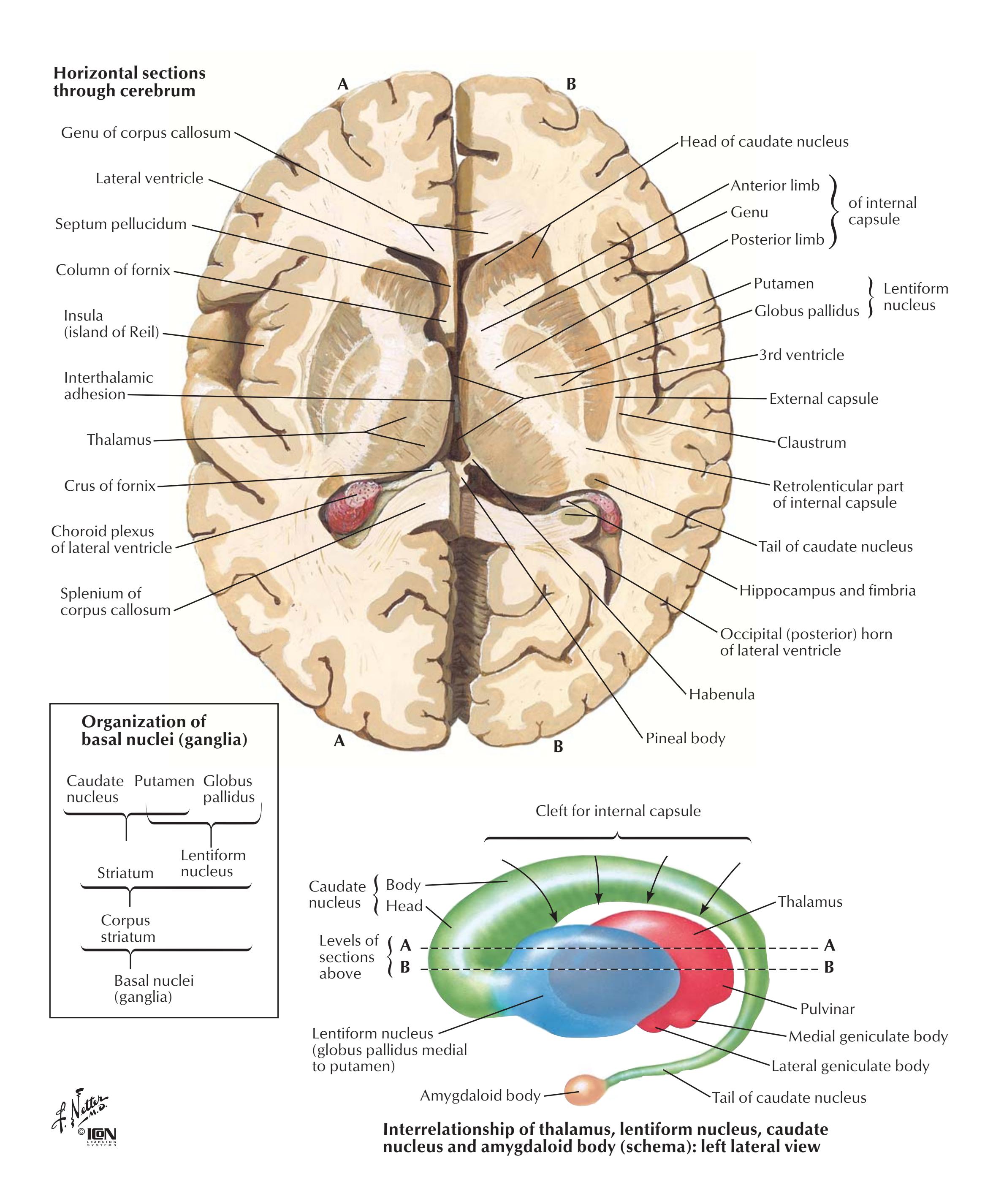

**Thalamus NEUROANATOMY**

**5**

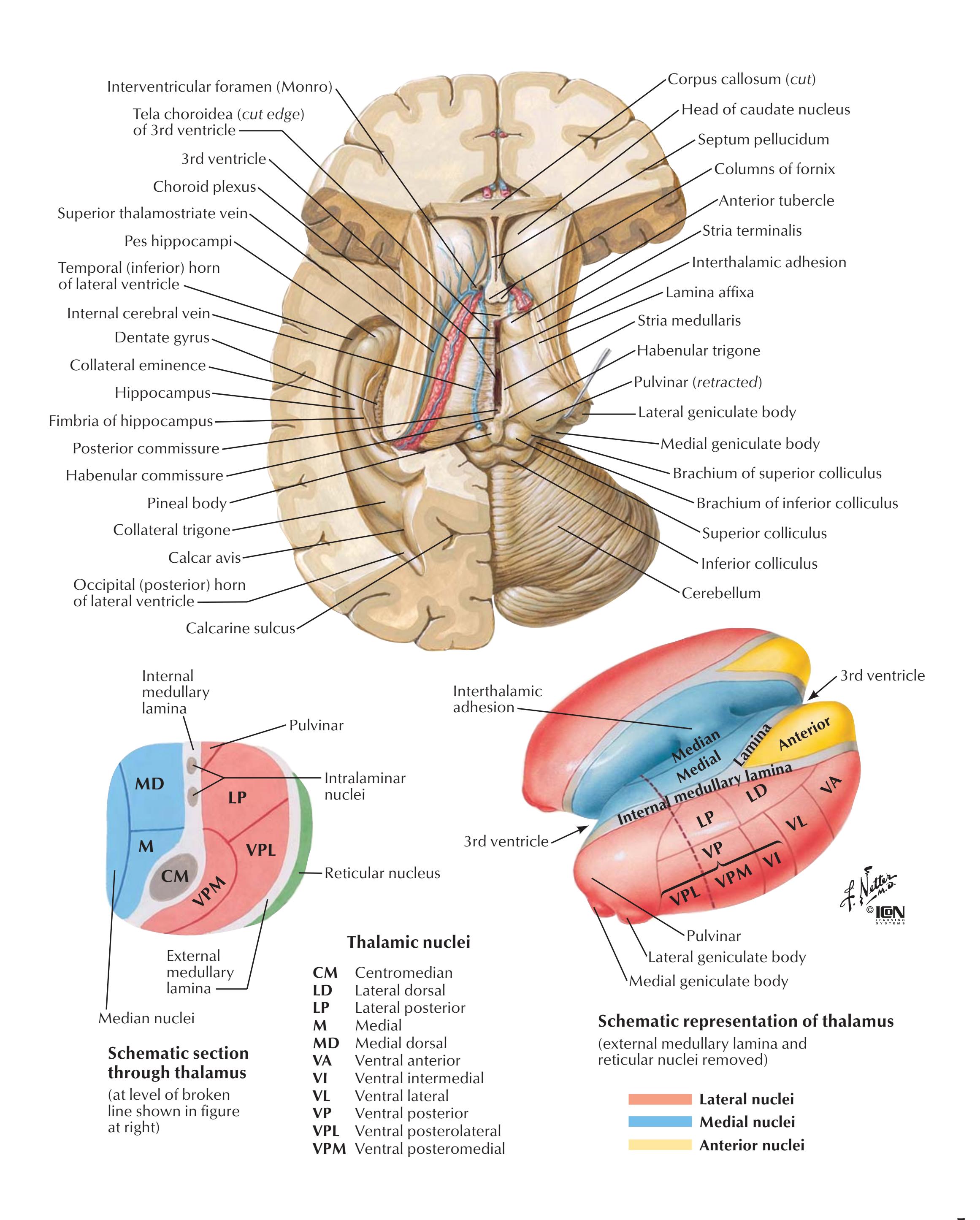

**NEUROANATOMY Cerebellum**

**6**

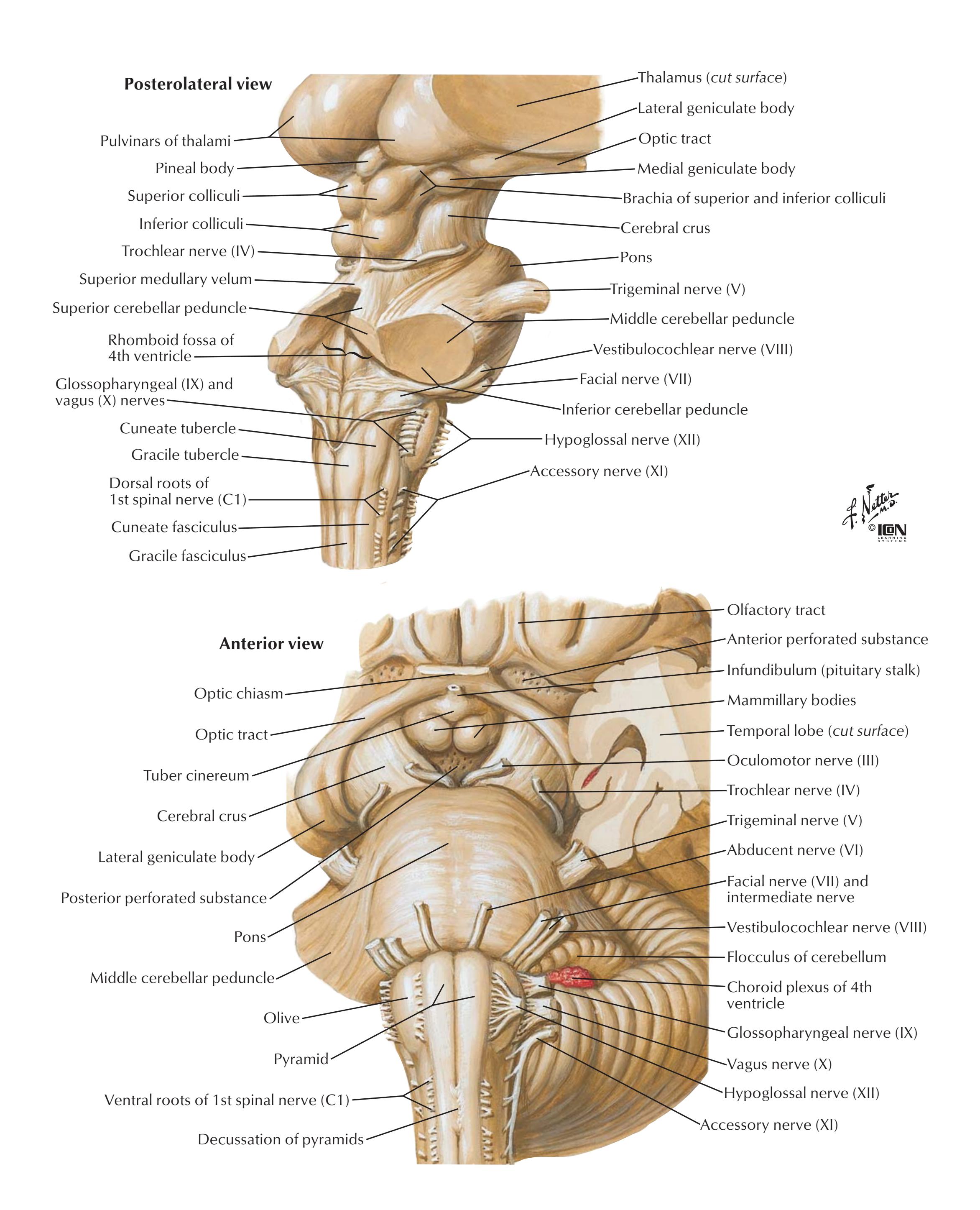

**Brainstem NEUROANATOMY**

**7**

**NEUROANATOMY Fourth Ventricle and Cerebellum**

**8**

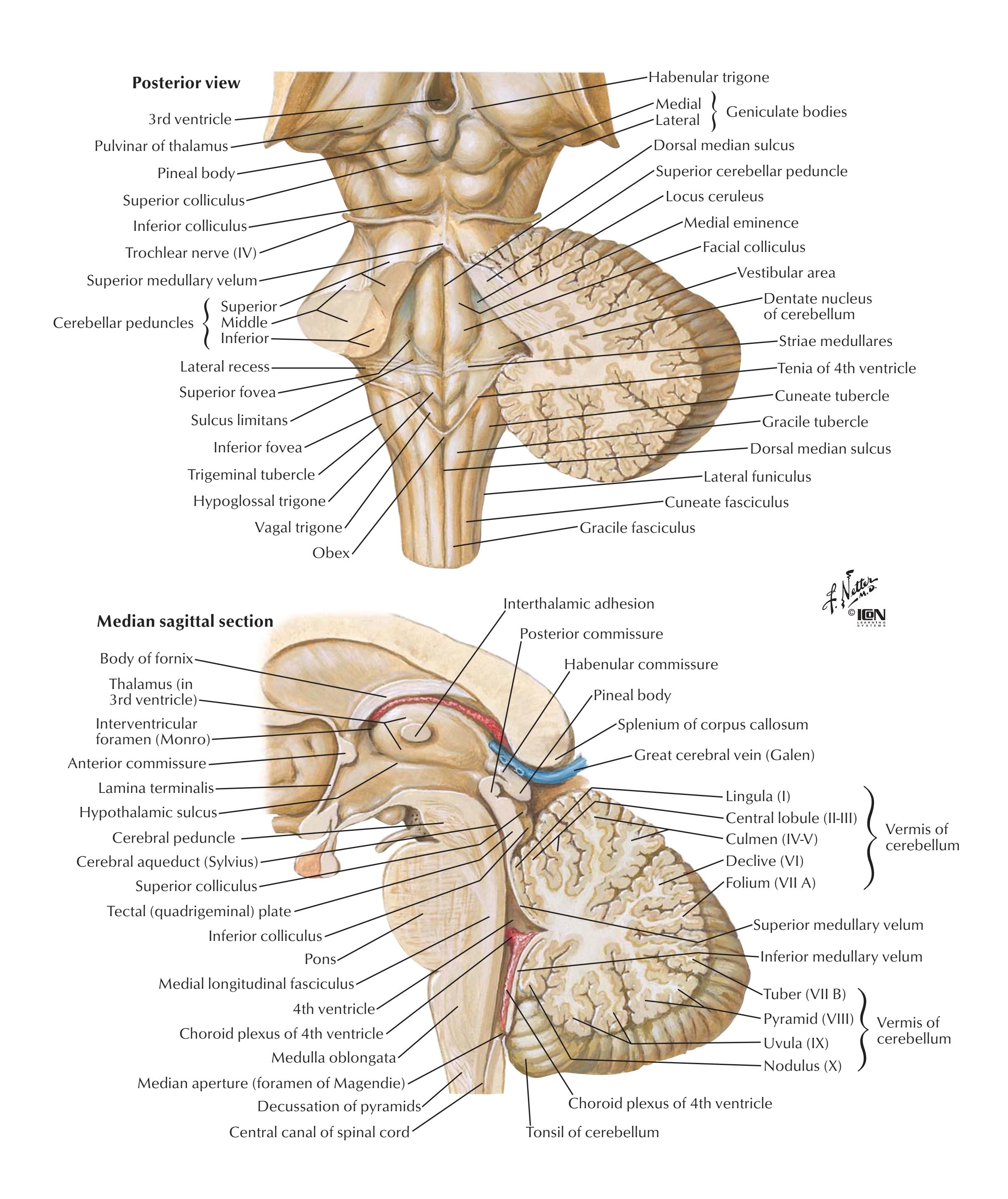

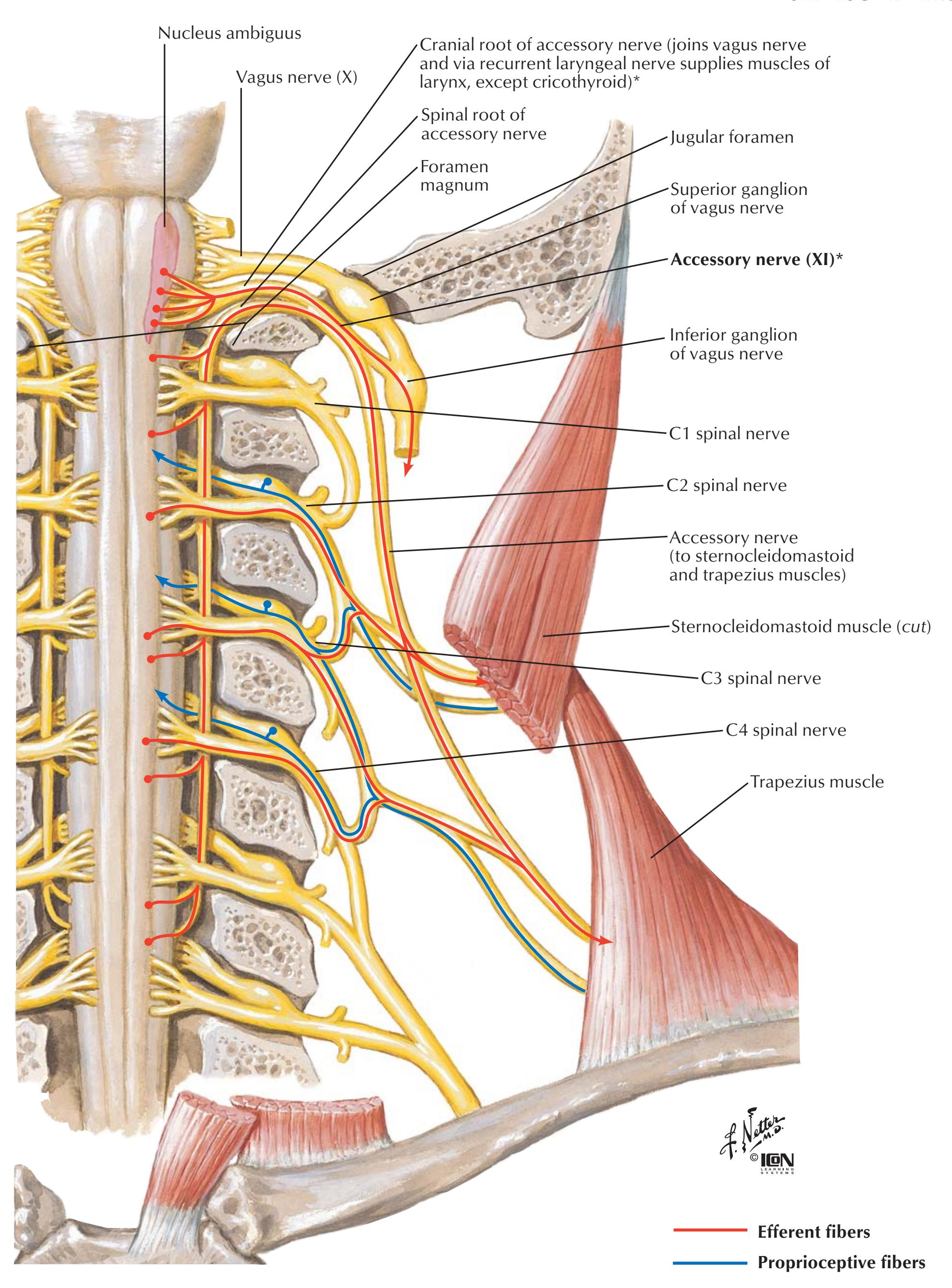

**Accessory Nerve (XI): Schema NEUROANATOMY**

\*Recent evidence suggests that the accessory nerve lacks a cranial root and has no connection to the vagus nerve. Verification of this finding awaits further investigation.

**9**

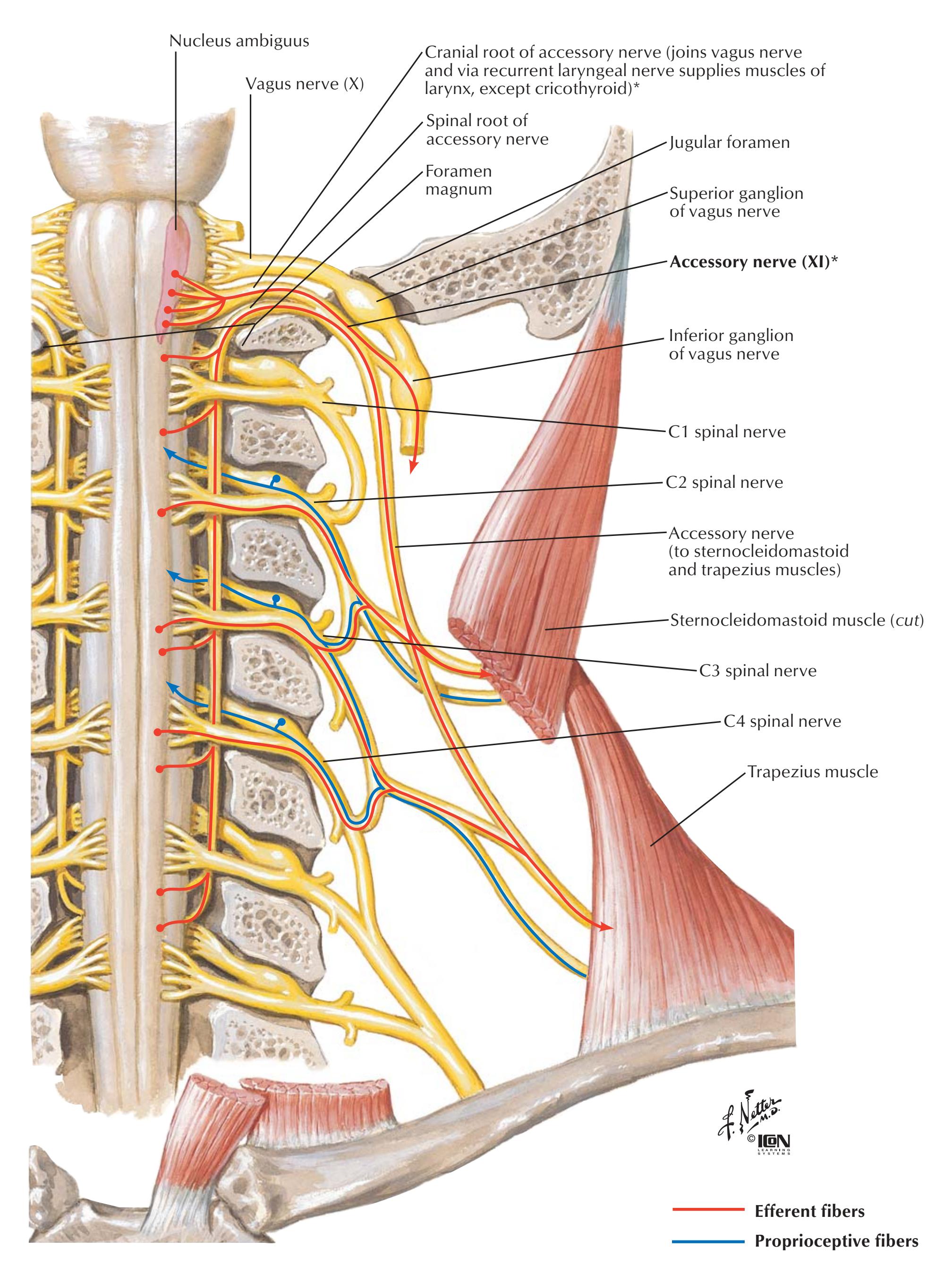

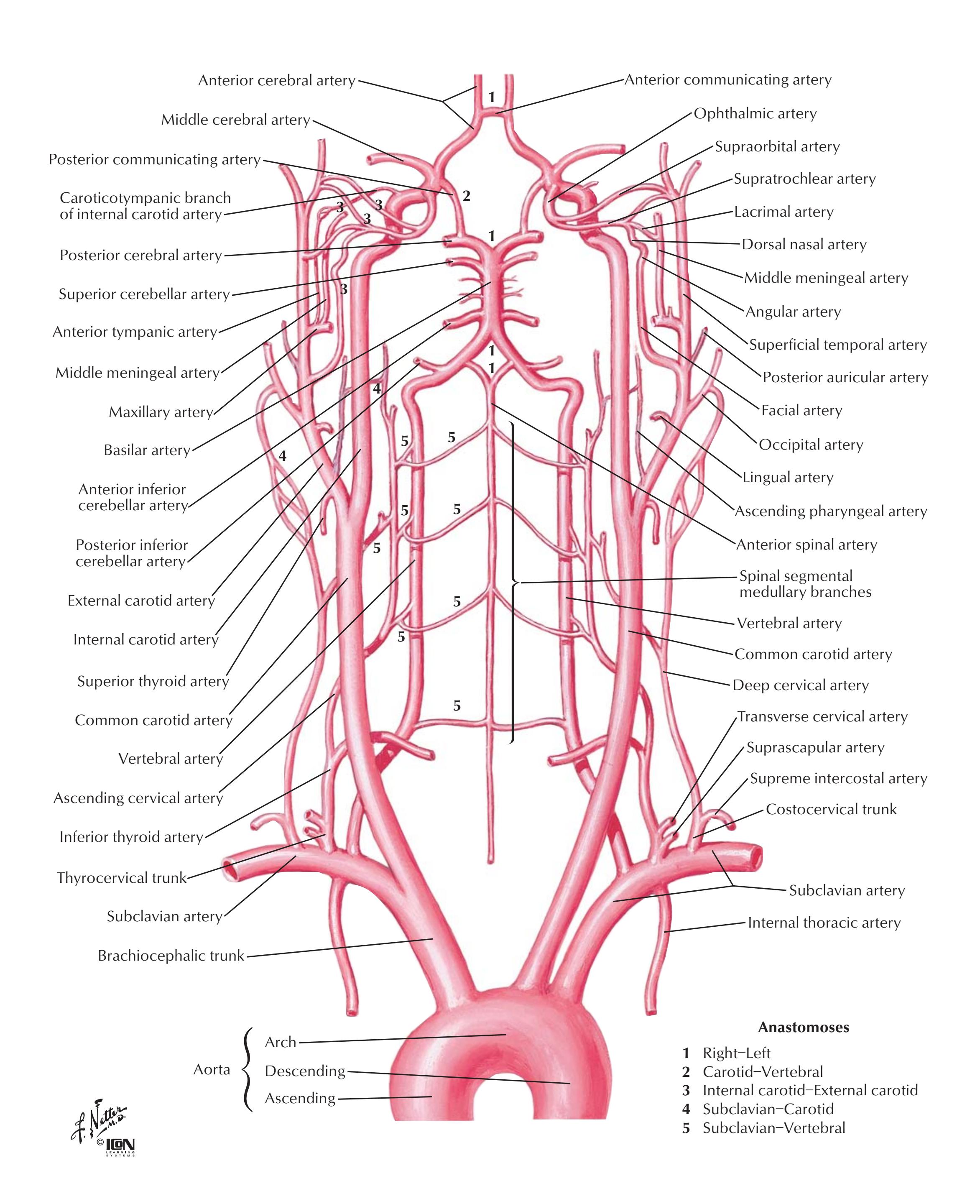

**NEUROANATOMY Arteries to Brain and Meninges**

**10**

**Arteries to Brain: Schema NEUROANATOMY**

**11**

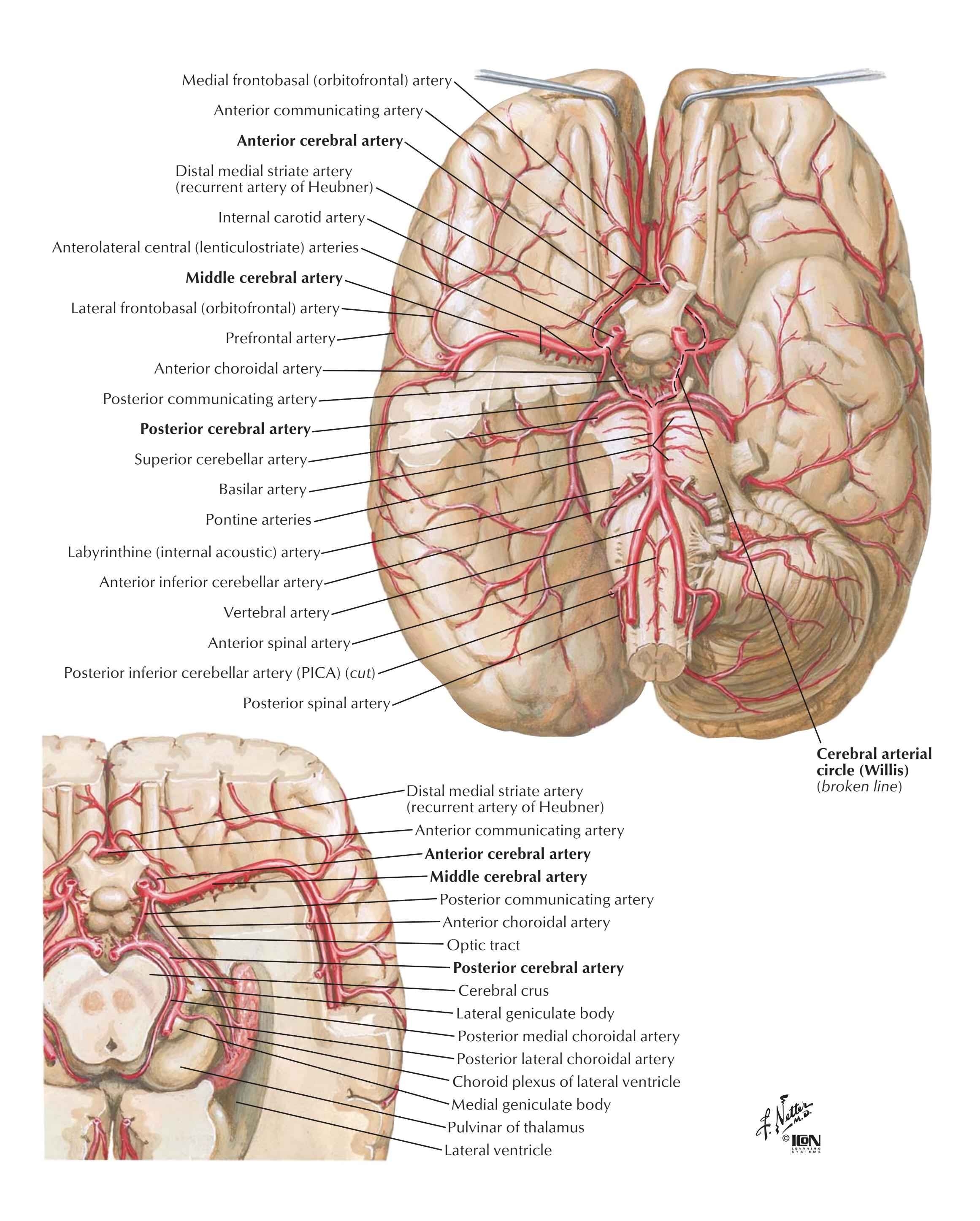

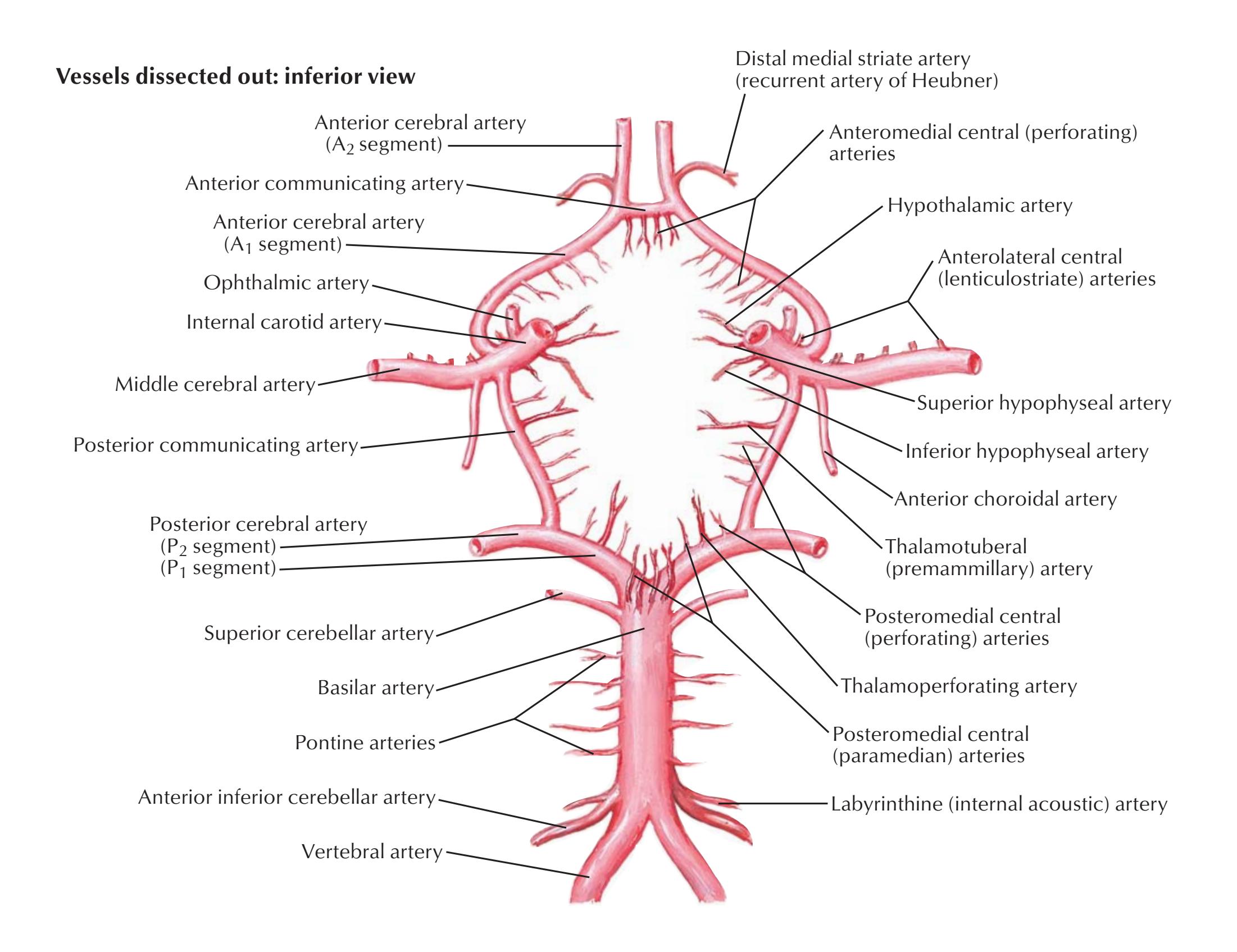

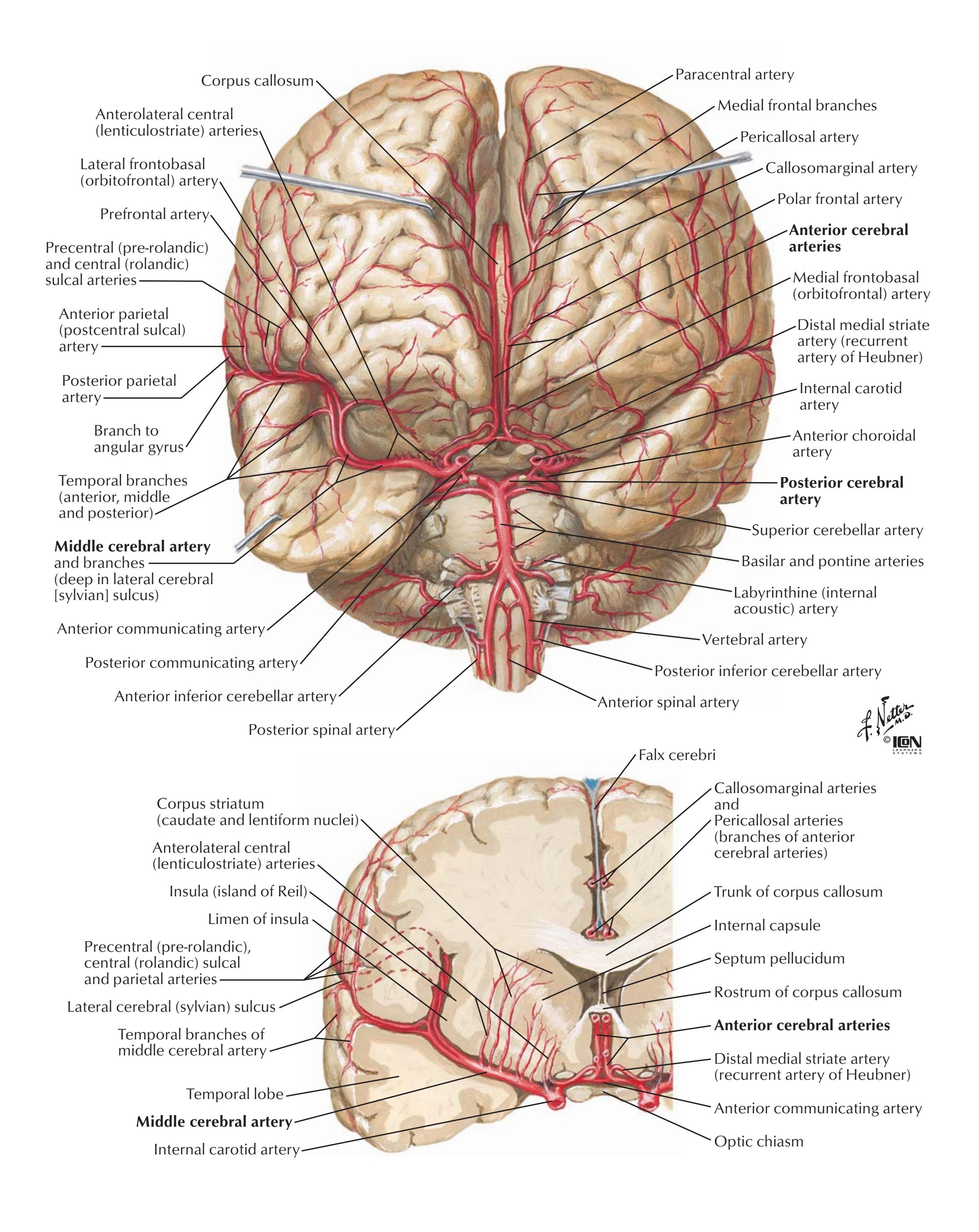

**NEUROANATOMY Arteries of Brain: Inferior Views**

**12**

**Cerebral Arterial Circle (Willis) NEUROANATOMY**

### Vessels in situ: inferior view

**13**

**NEUROANATOMY Arteries of Brain: Frontal View and Section**

**14**

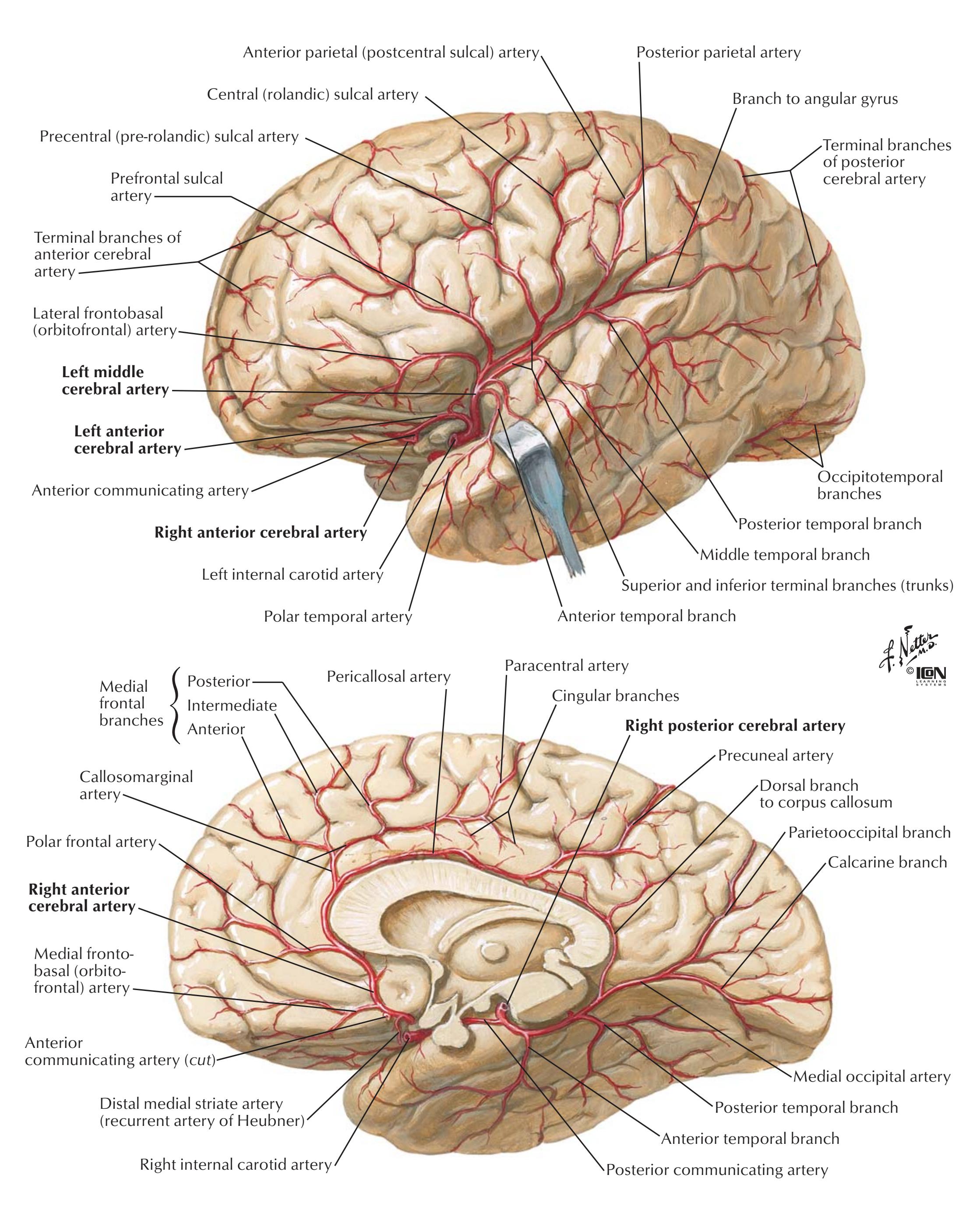

**Arteries of Brain: Lateral and Medial Views NEUROANATOMY**

Note: Anterior parietal (postcentral sulcal) artery also occurs as separate anterior parietal and postcentral sulcal arteries

**15**

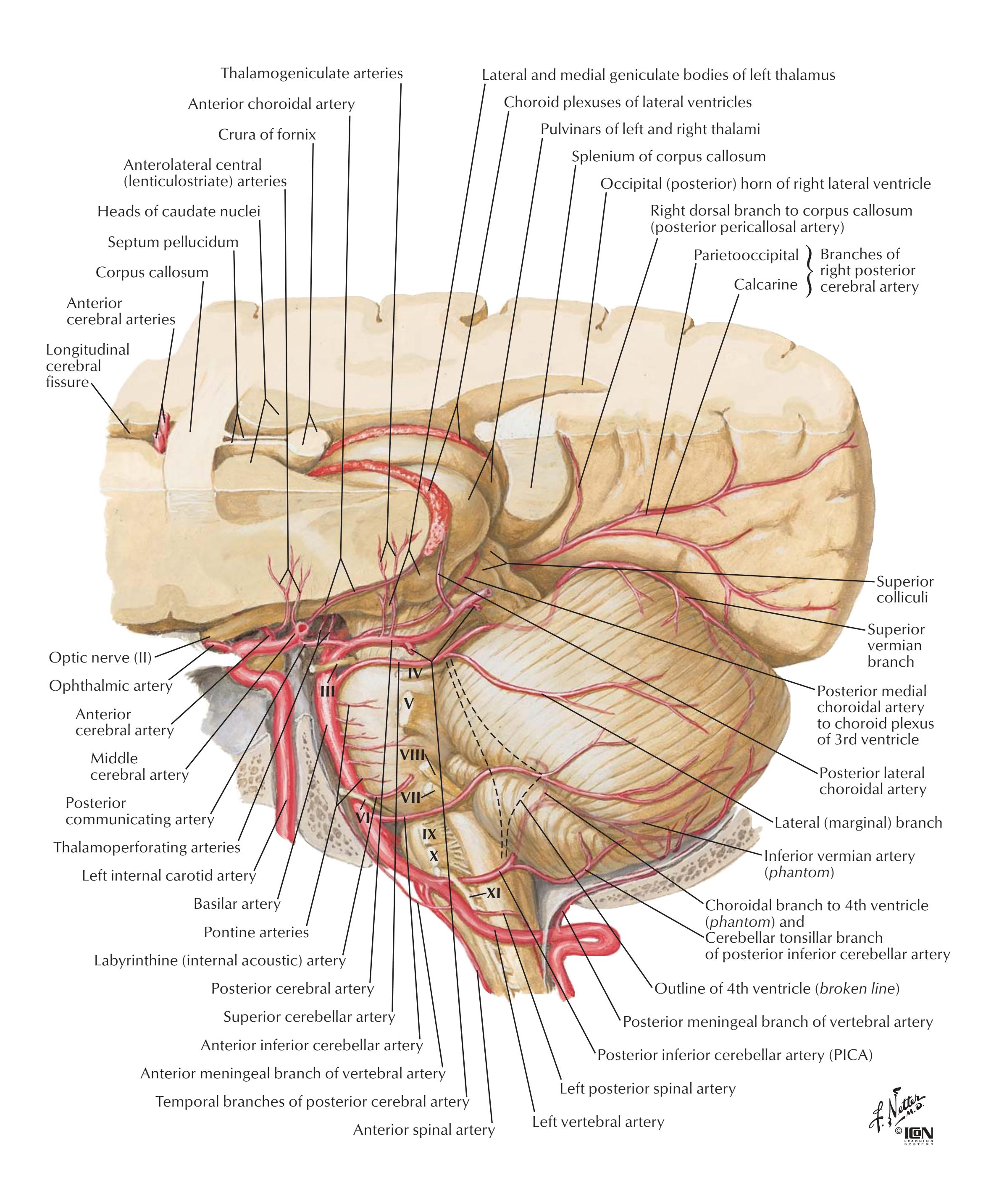

**NEUROANATOMY Arteries of Posterior Cranial Fossa**

**16**

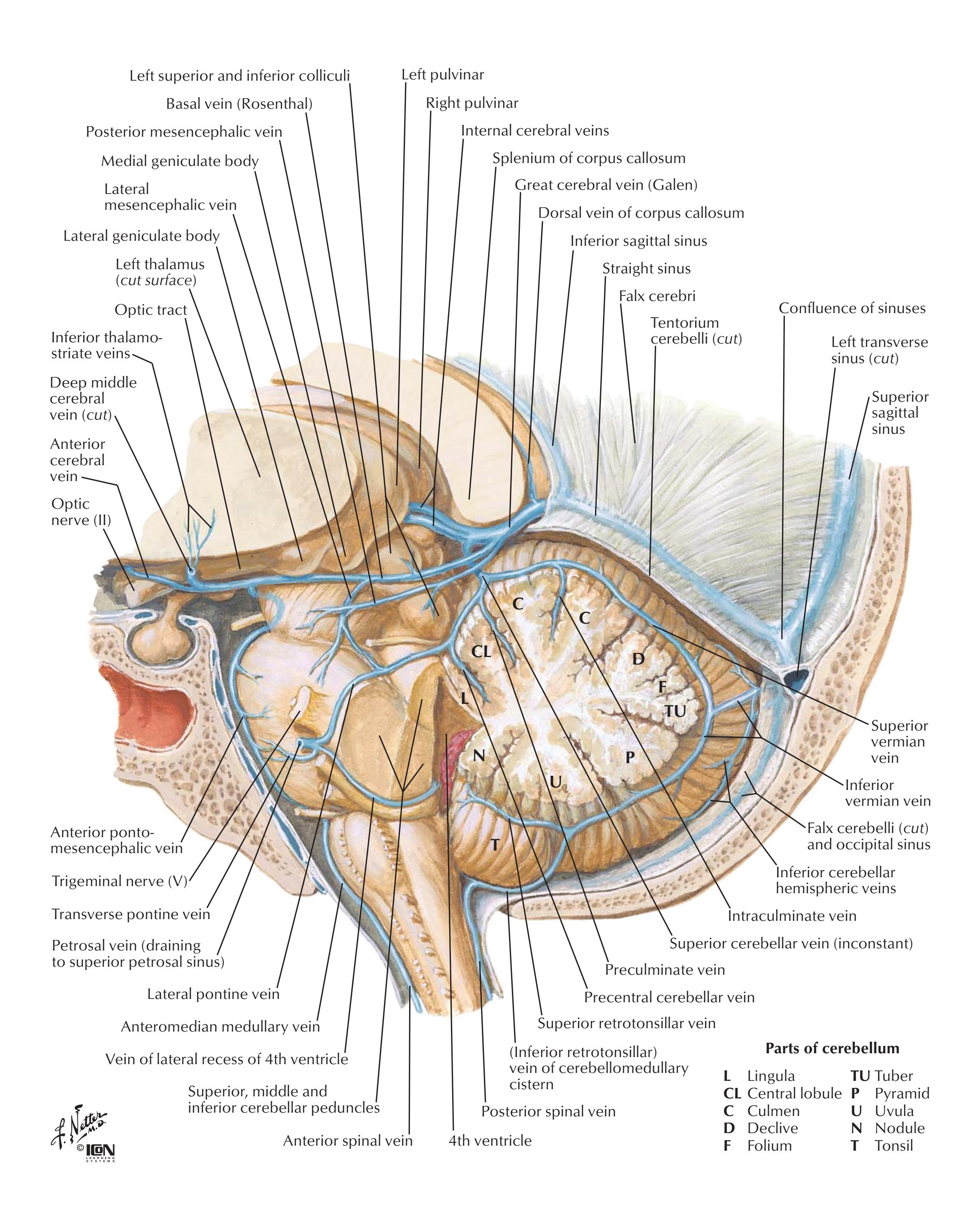

**Veins of Posterior Cranial Fossa NEUROANATOMY**

**17**

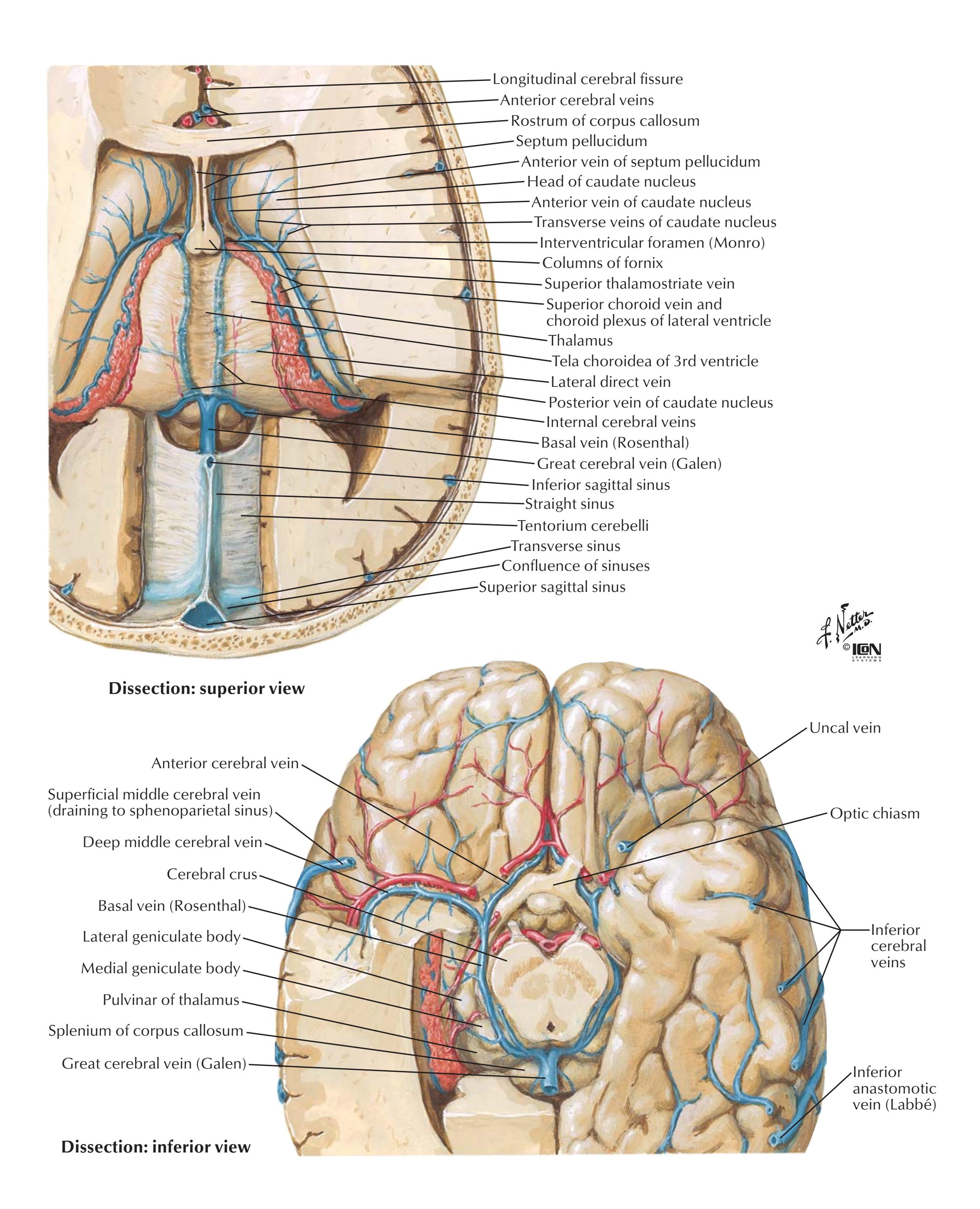

**NEUROANATOMY Deep Veins of Brain**

**18**

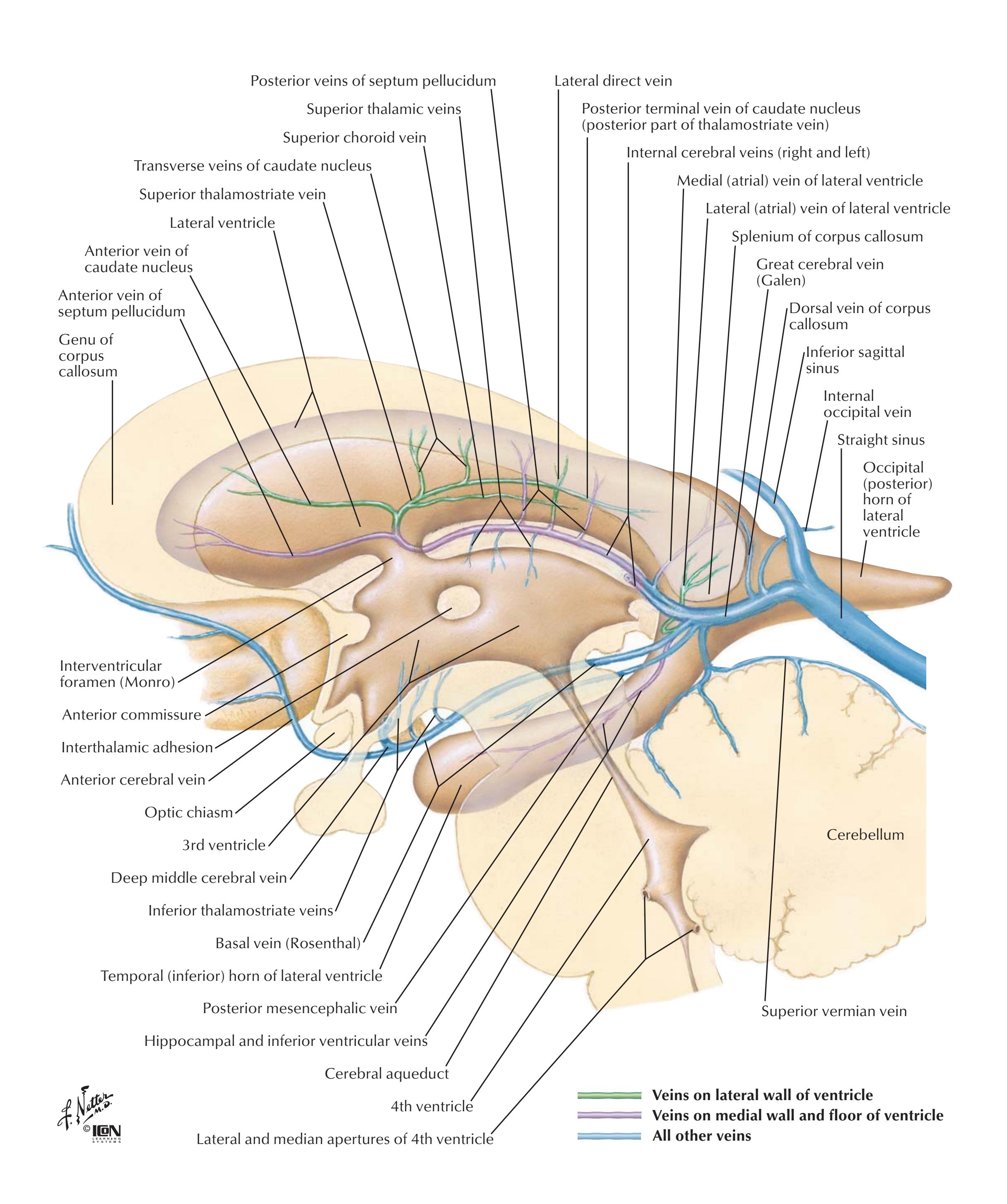

**Subependymal Veins of Brain NEUROANATOMY**

**19**

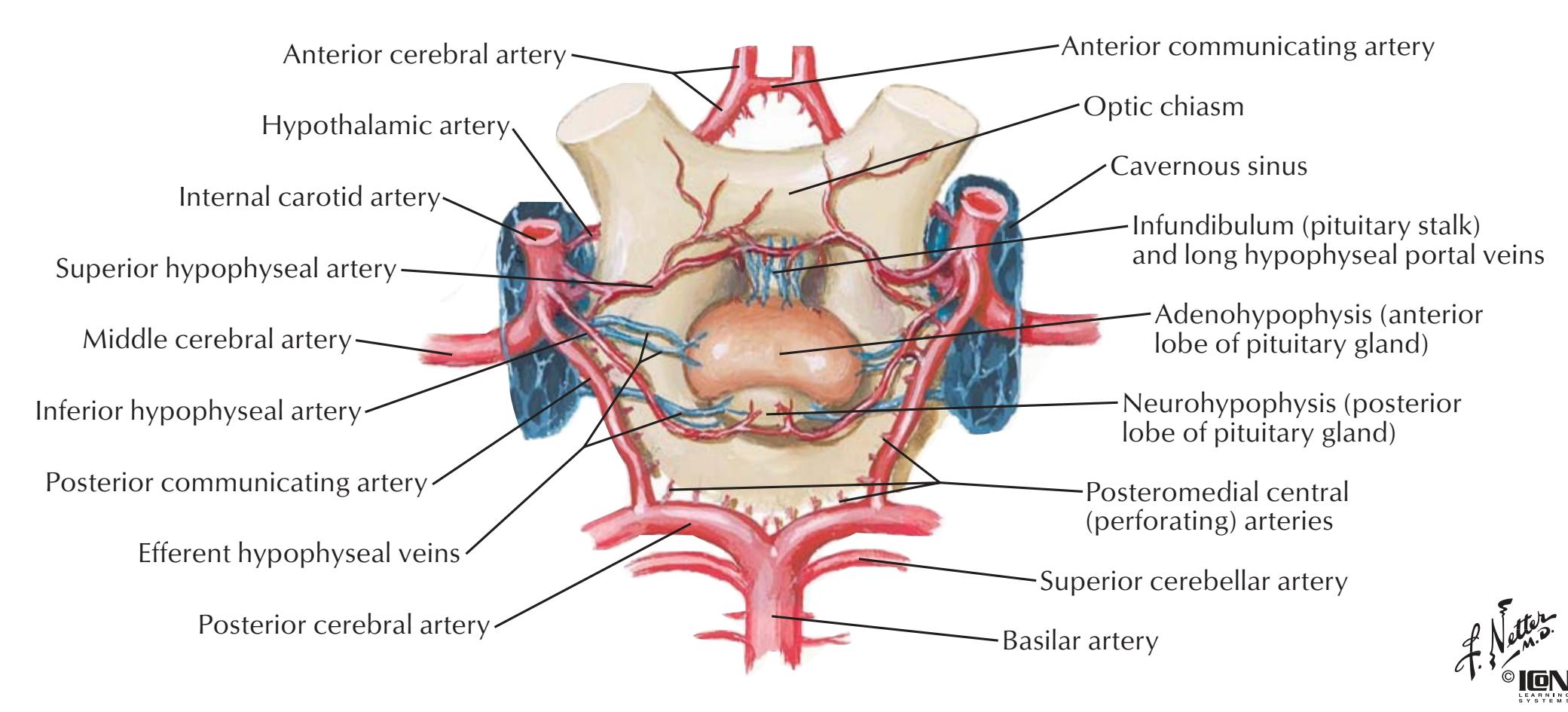

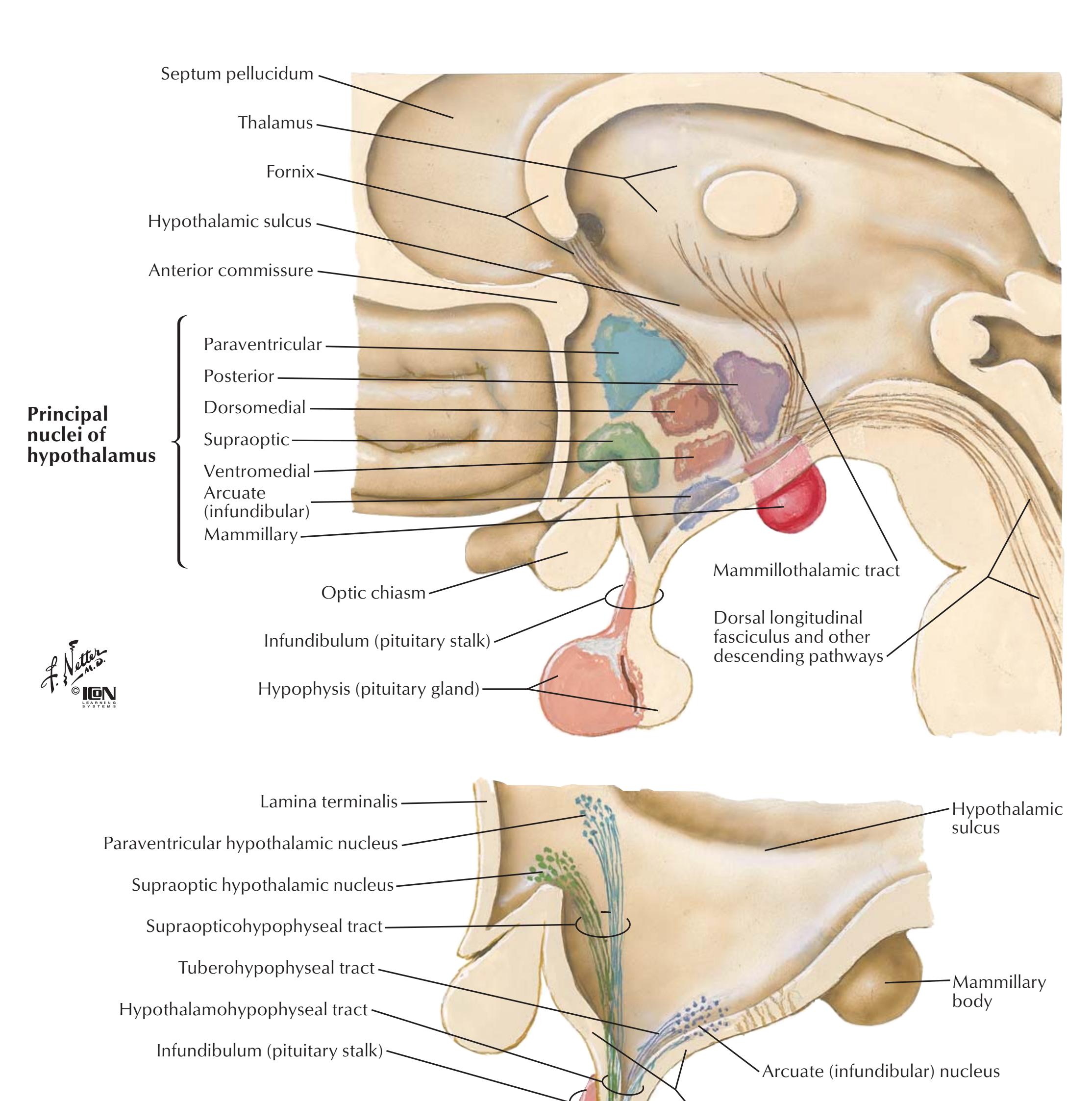

**NEUROANATOMY Hypothalamus and Hypophysis**

Neurohypophysis (posterior lobe of pituitary gland)

Adenohypophysis (anterior lobe of pituitary gland)

Fibrous trabecula Pars intermedia Pars distalis Cleft Pars tuberalis Median eminence of tuber cinereum Infundibular stem Infundibular process

**20**

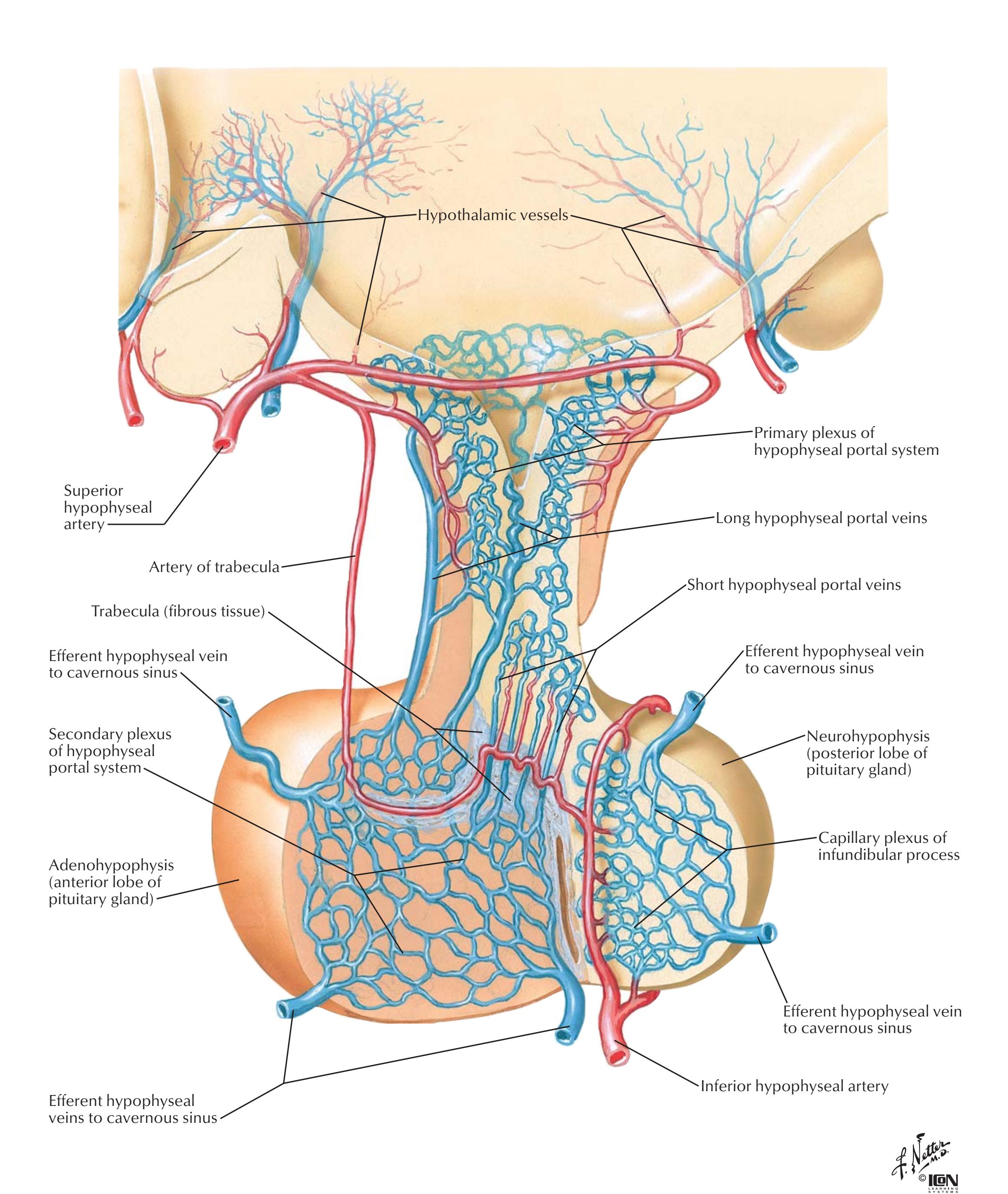

**Arteries and Veins of Hypothalamus and Hypophysis NEUROANATOMY**

**21**

**NEUROANATOMY Relation of Spinal Nerve Roots to Vertebrae**

**22**

**Autonomic Nervous System: General Topography NEUROANATOMY**

**23**

**NEUROANATOMY Spinal Nerve Origin: Cross Sections**

**24**

**Olfactory Nerve (I): Schema NEUROANATOMY**

**25**

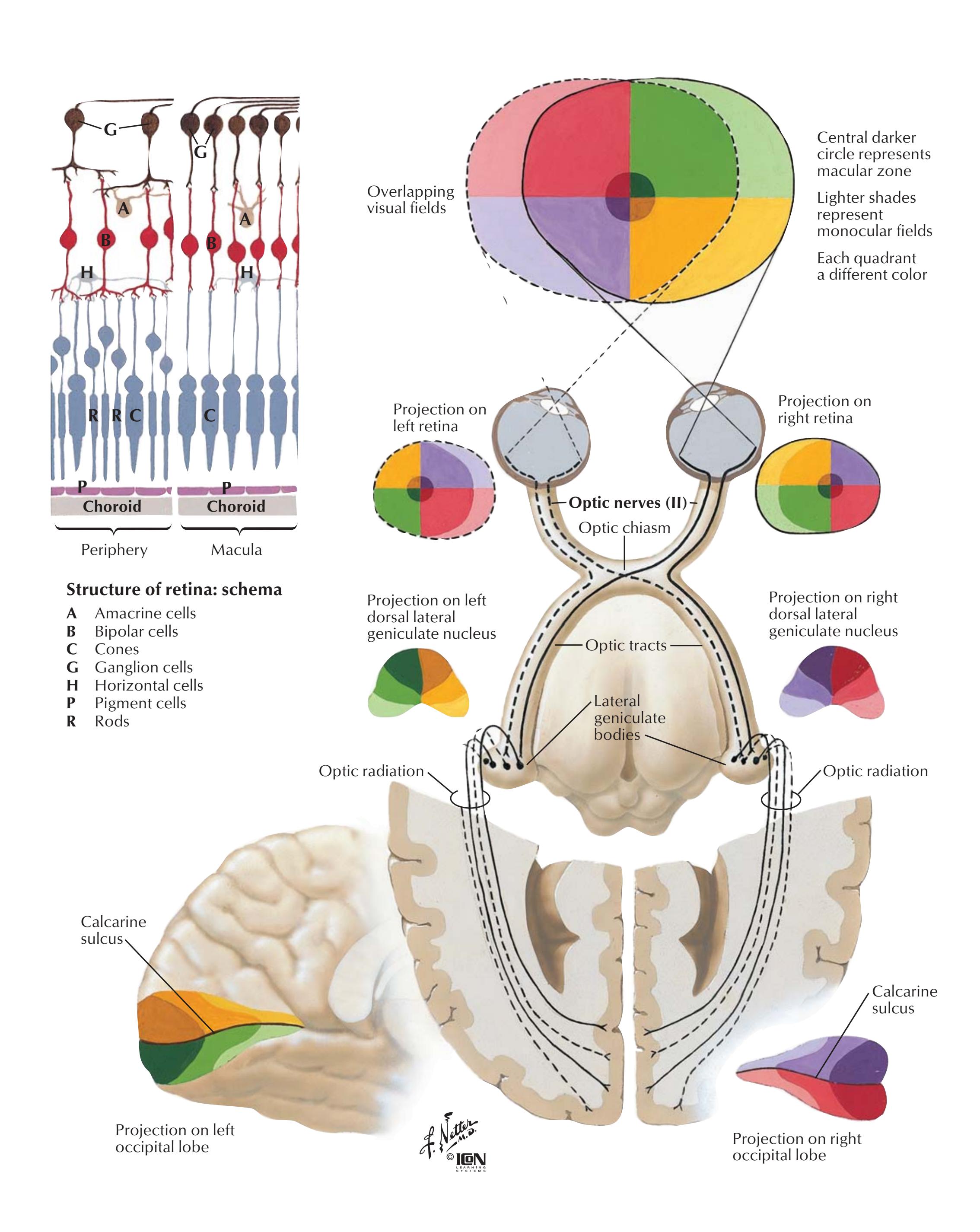

**NEUROANATOMY Optic Nerve (II) (Visual Pathway): Schema**

**26**

**Oculomotor (III), Trochlear (IV) and Abducent (VI) Nerves: Schema NEUROANATOMY**

**27**

**NEUROANATOMY Trigeminal Nerve (V): Schema**

**28**

**Facial Nerve (VII): Schema NEUROANATOMY**

**29**

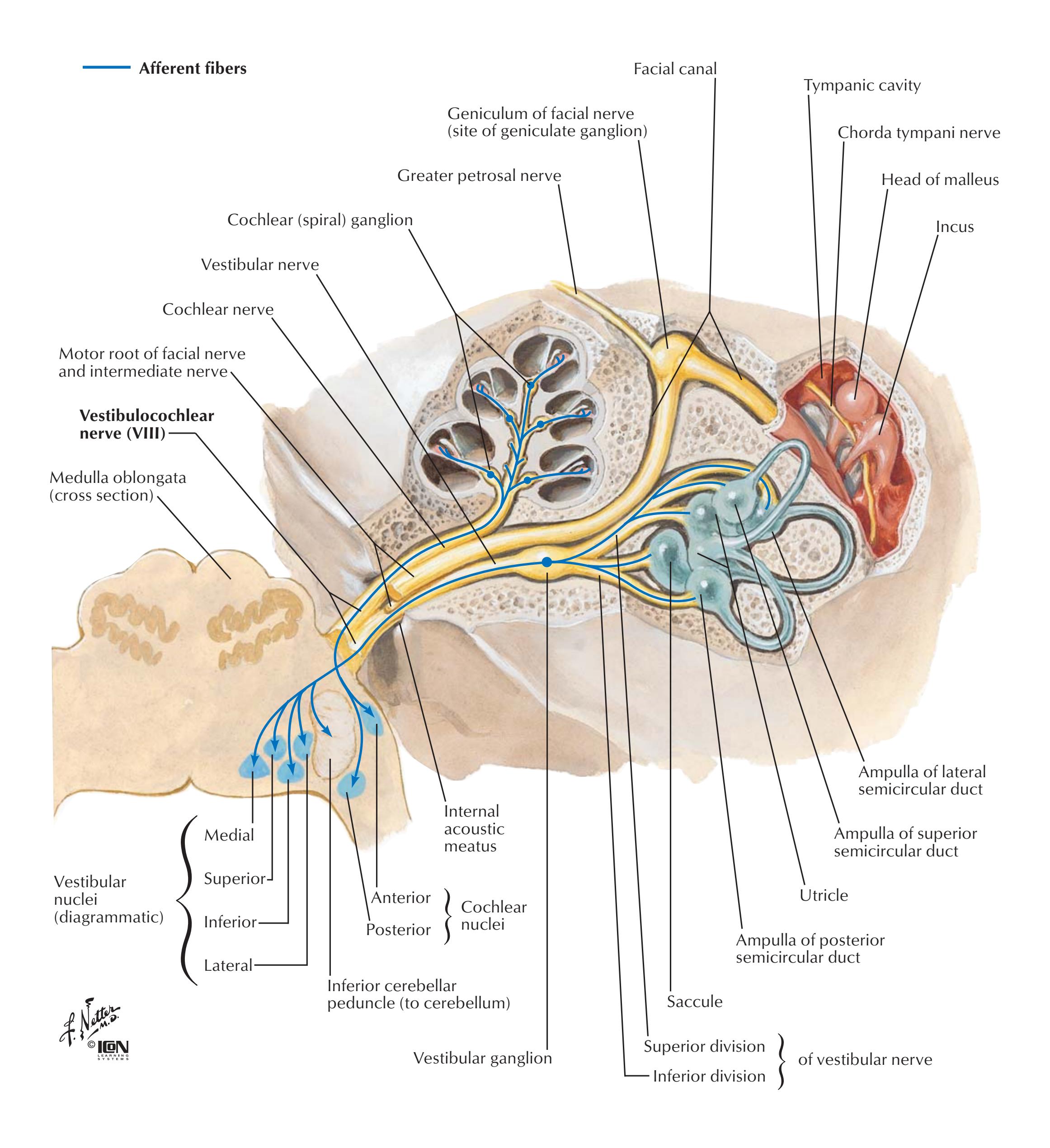

**NEUROANATOMY Vestibulocochlear Nerve (VIII): Schema**

**30**

**Glossopharyngeal Nerve (IX): Schema NEUROANATOMY**

**31**

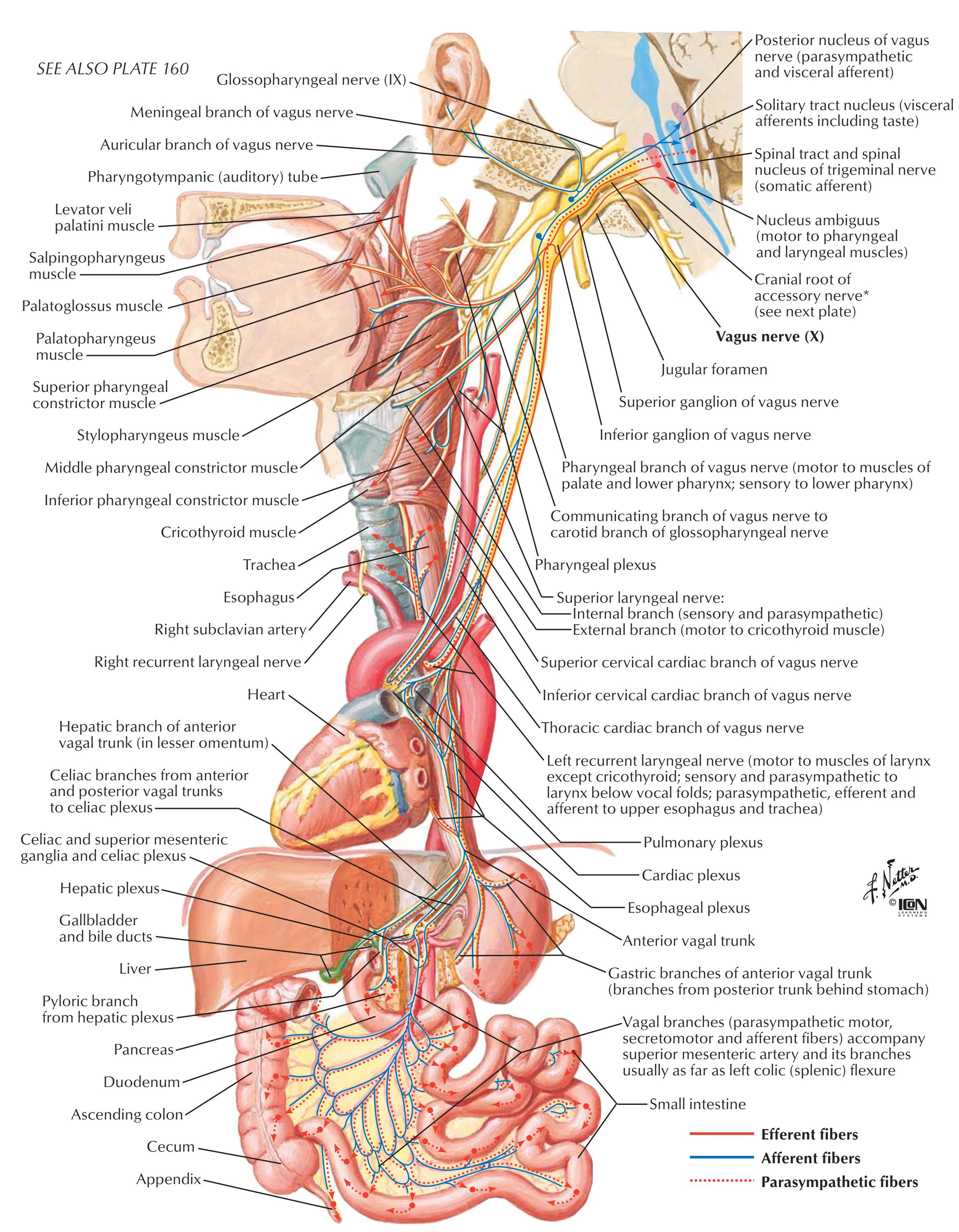

**NEUROANATOMY Vagus Nerve (X): Schema**

**32**

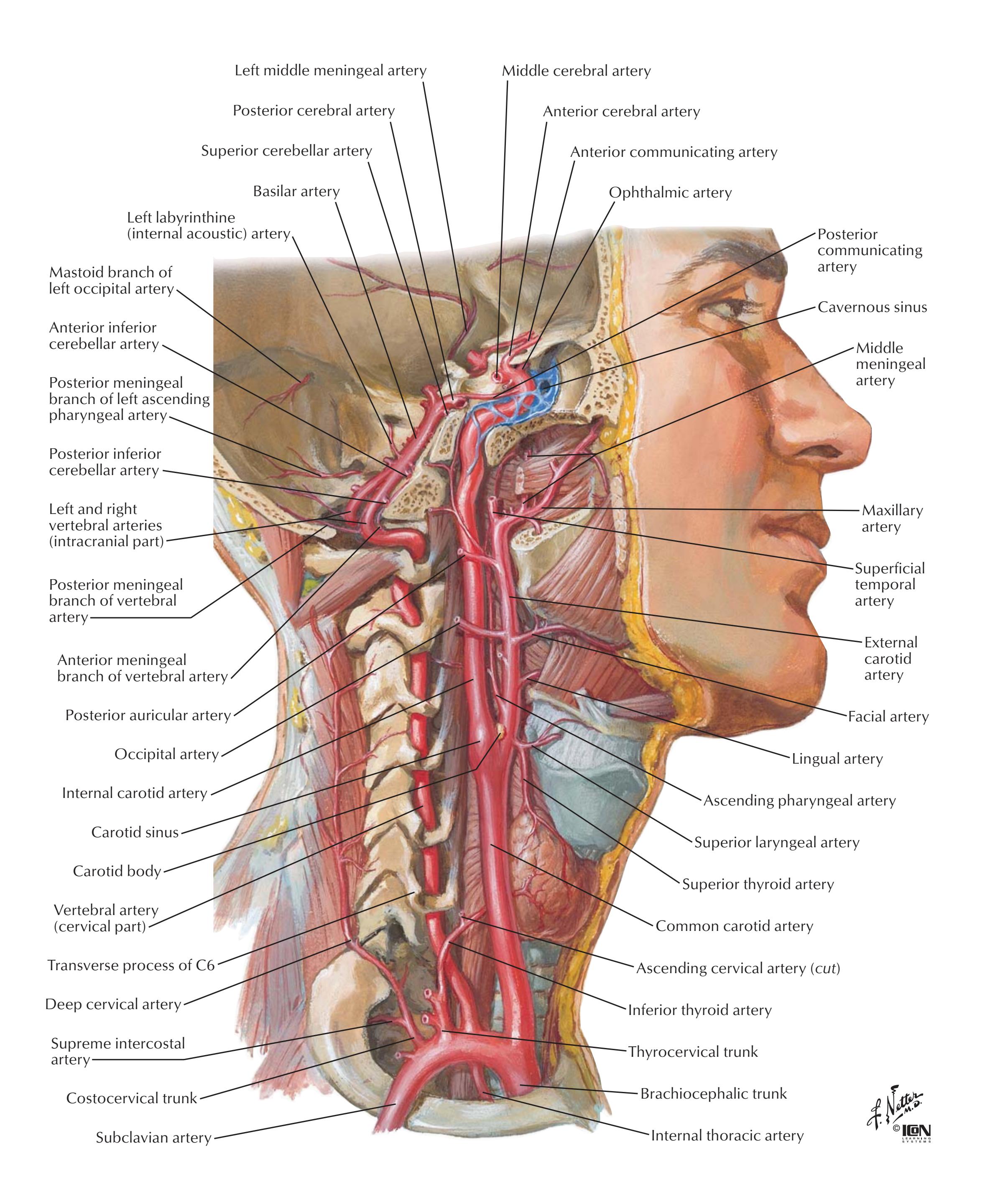

**Accessory Nerve (XI): Schema NEUROANATOMY**

*SEE ALSO PLATE 28*

\*Recent evidence suggests that the accessory nerve lacks a cranial root and has no connection to the vagus nerve. Verification of this finding awaits further investigation.

**33**

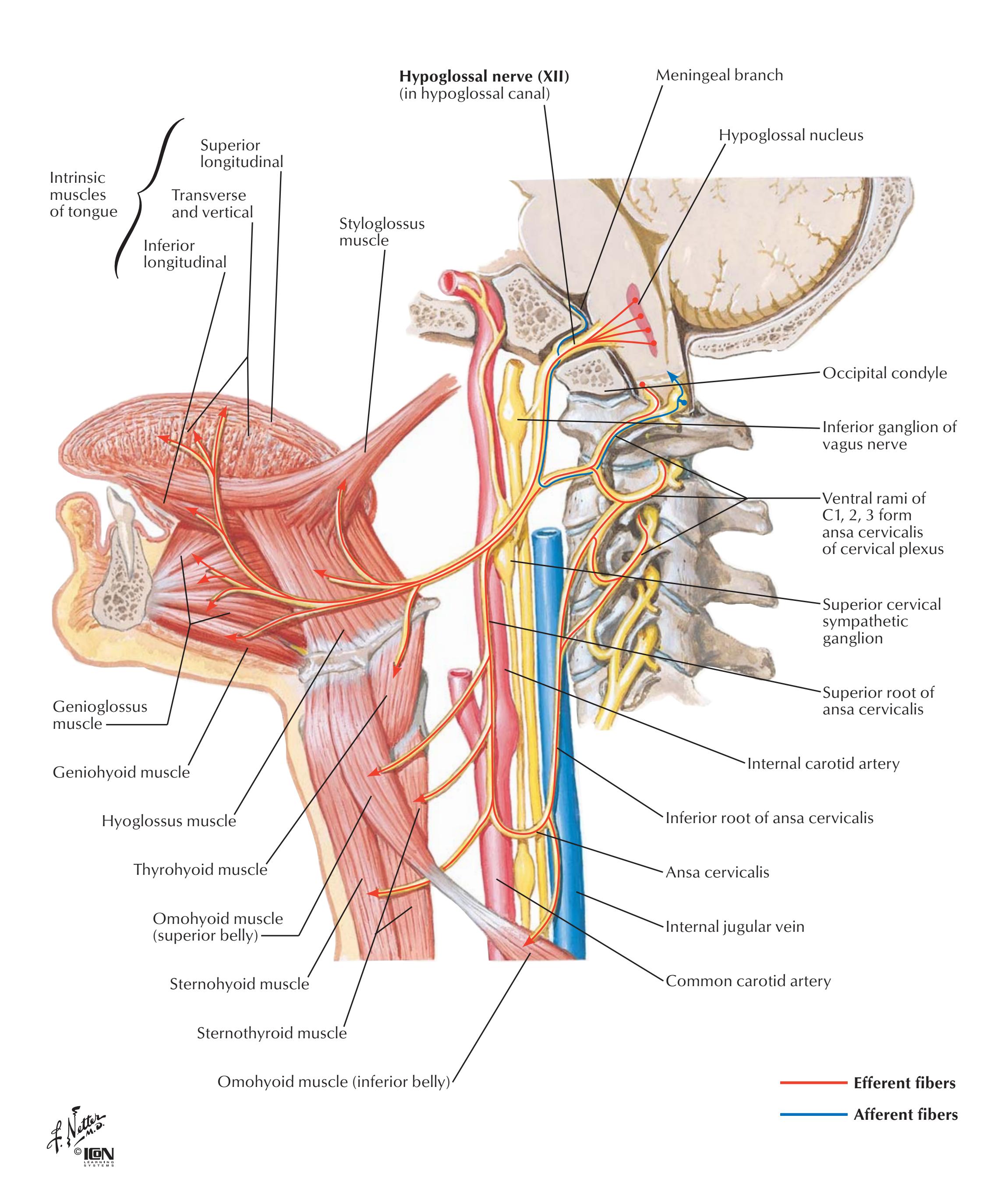

**NEUROANATOMY Hypoglossal Nerve (XII): Schema**

**34**

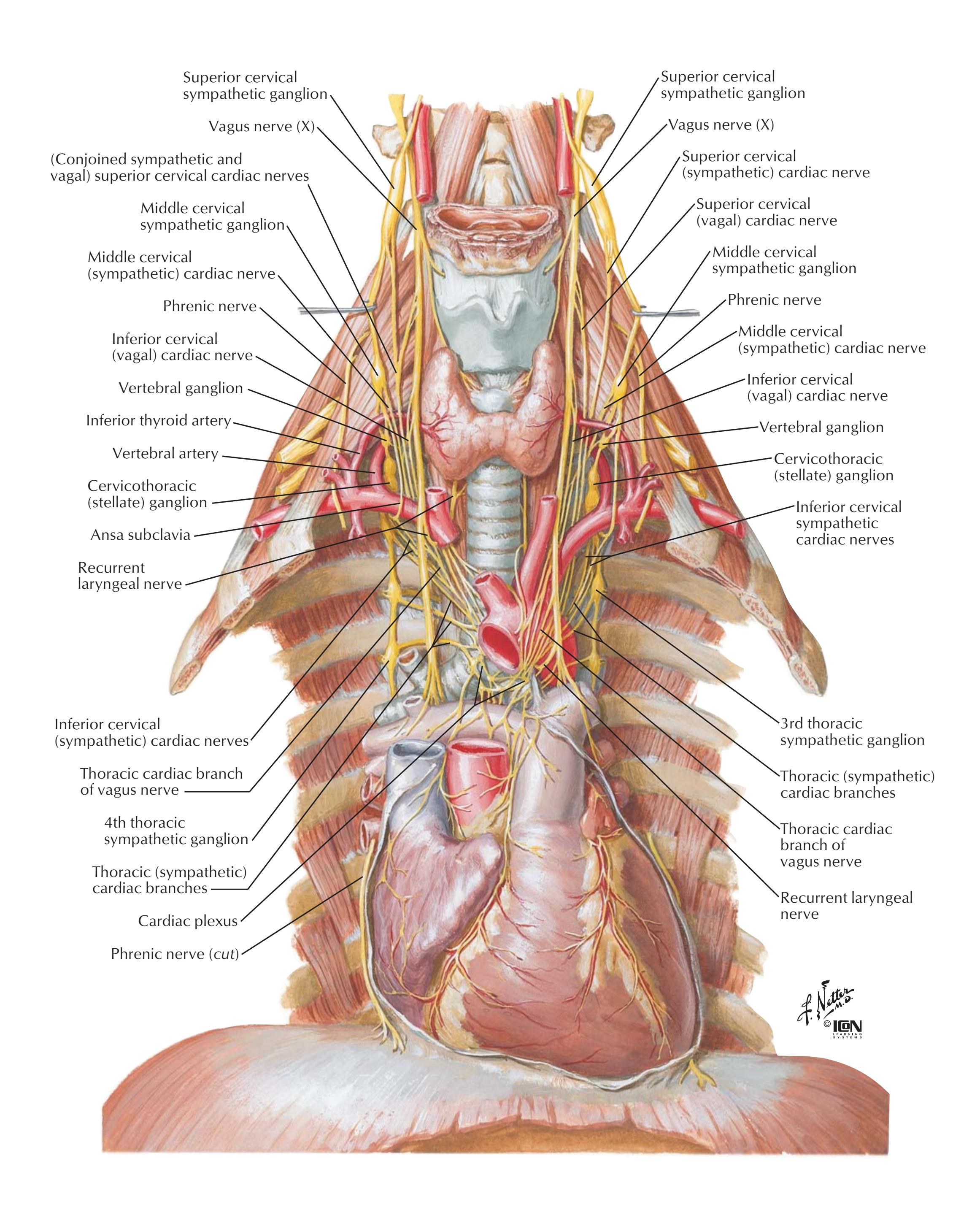

**Nerves of Heart NEUROANATOMY**

**35**

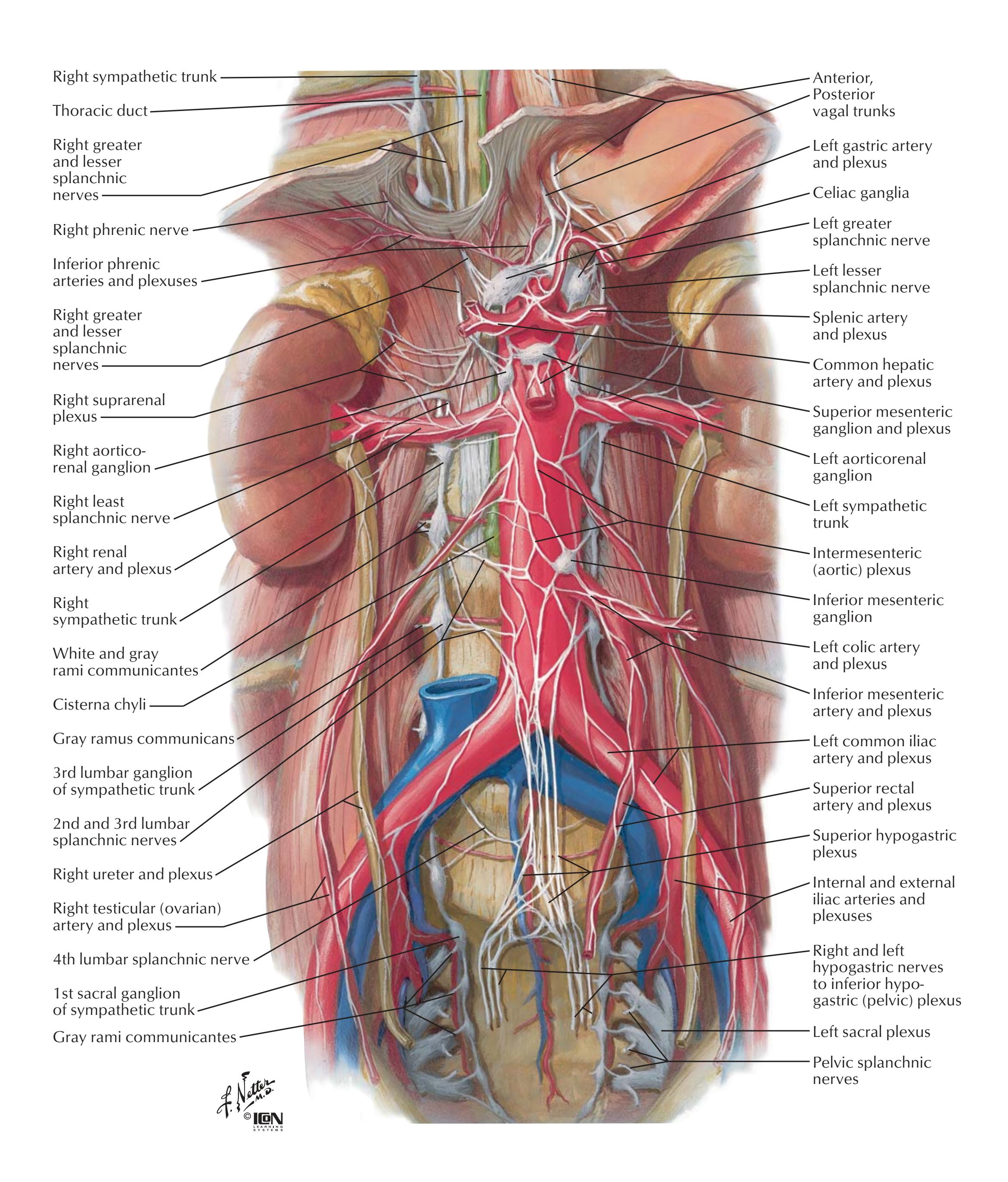

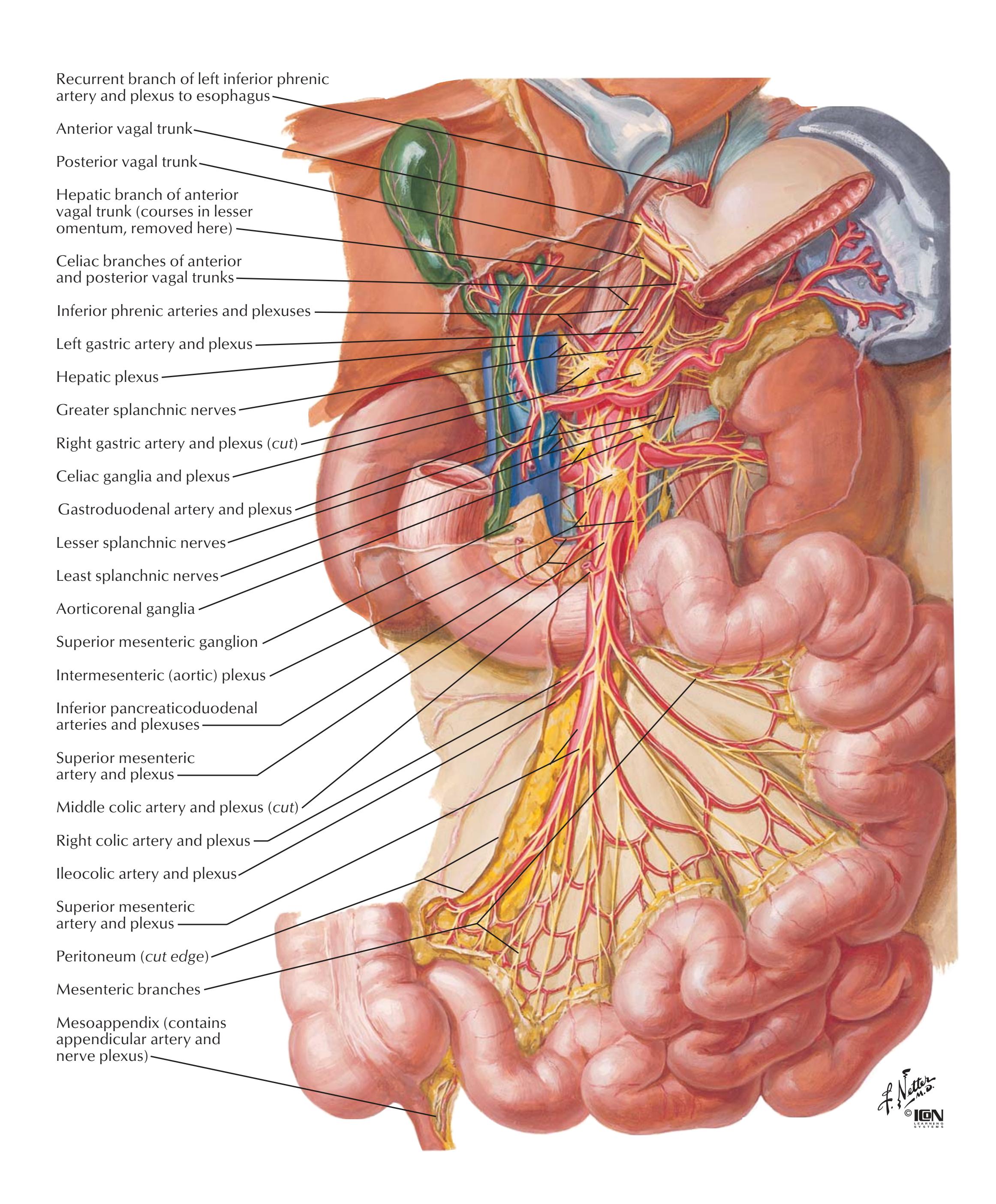

**NEUROANATOMY Autonomic Nerves and Ganglia of Abdomen**

**36**

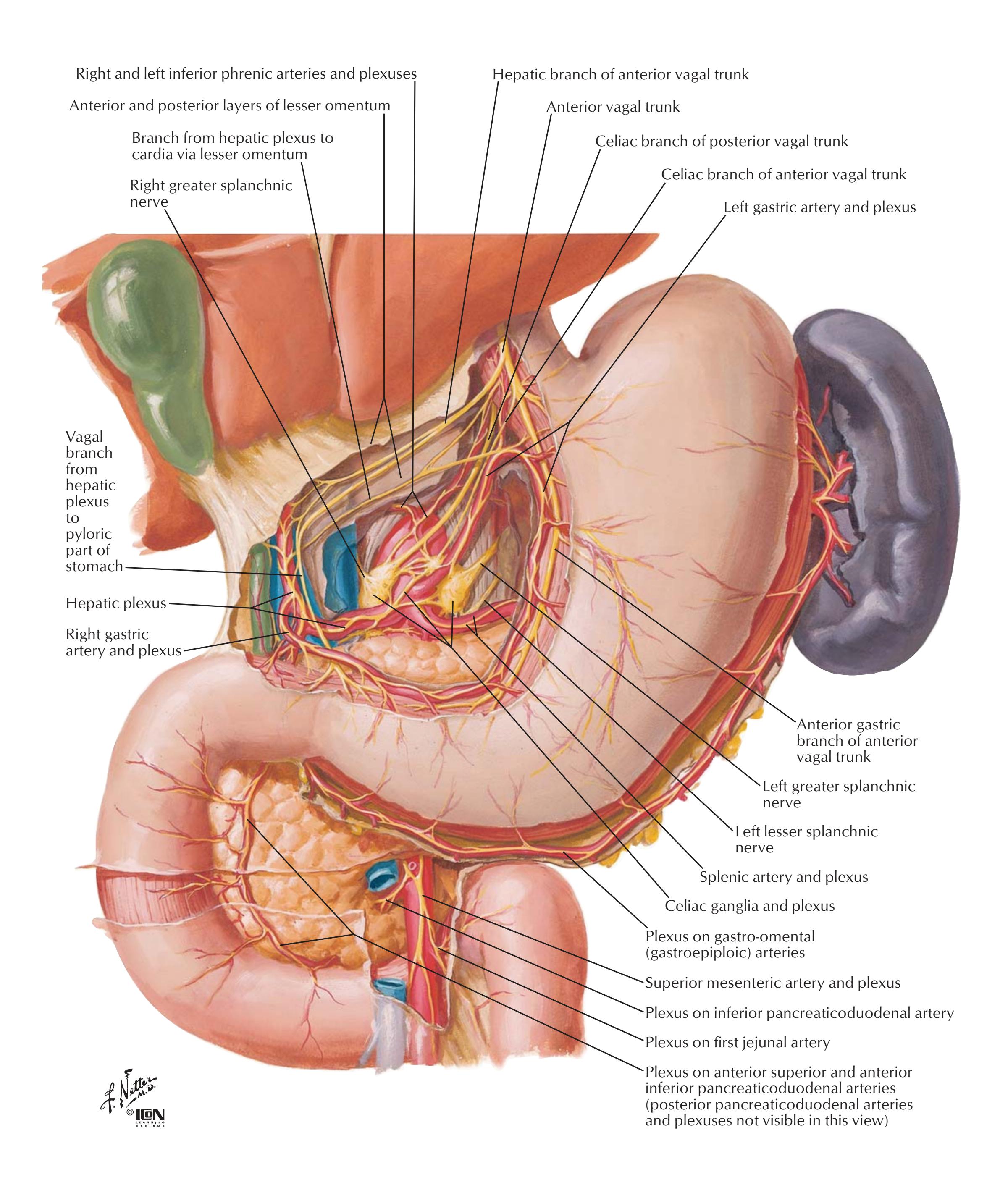

**Nerves of Stomach and Duodenum NEUROANATOMY**

**37**

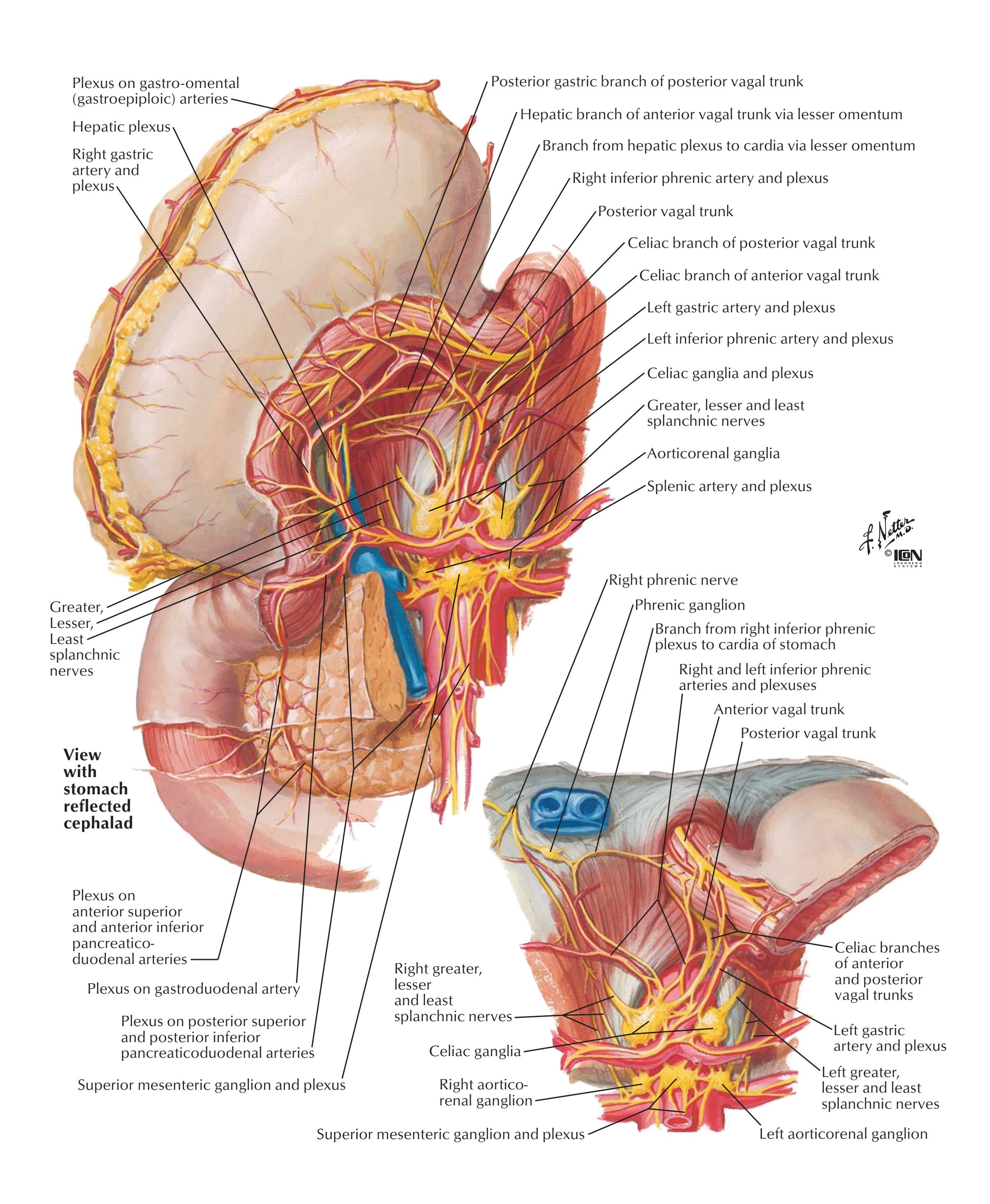

**NEUROANATOMY Nerves of Stomach and Duodenum (continued)**

**38**

**Nerves of Small Intestine NEUROANATOMY**

**39**

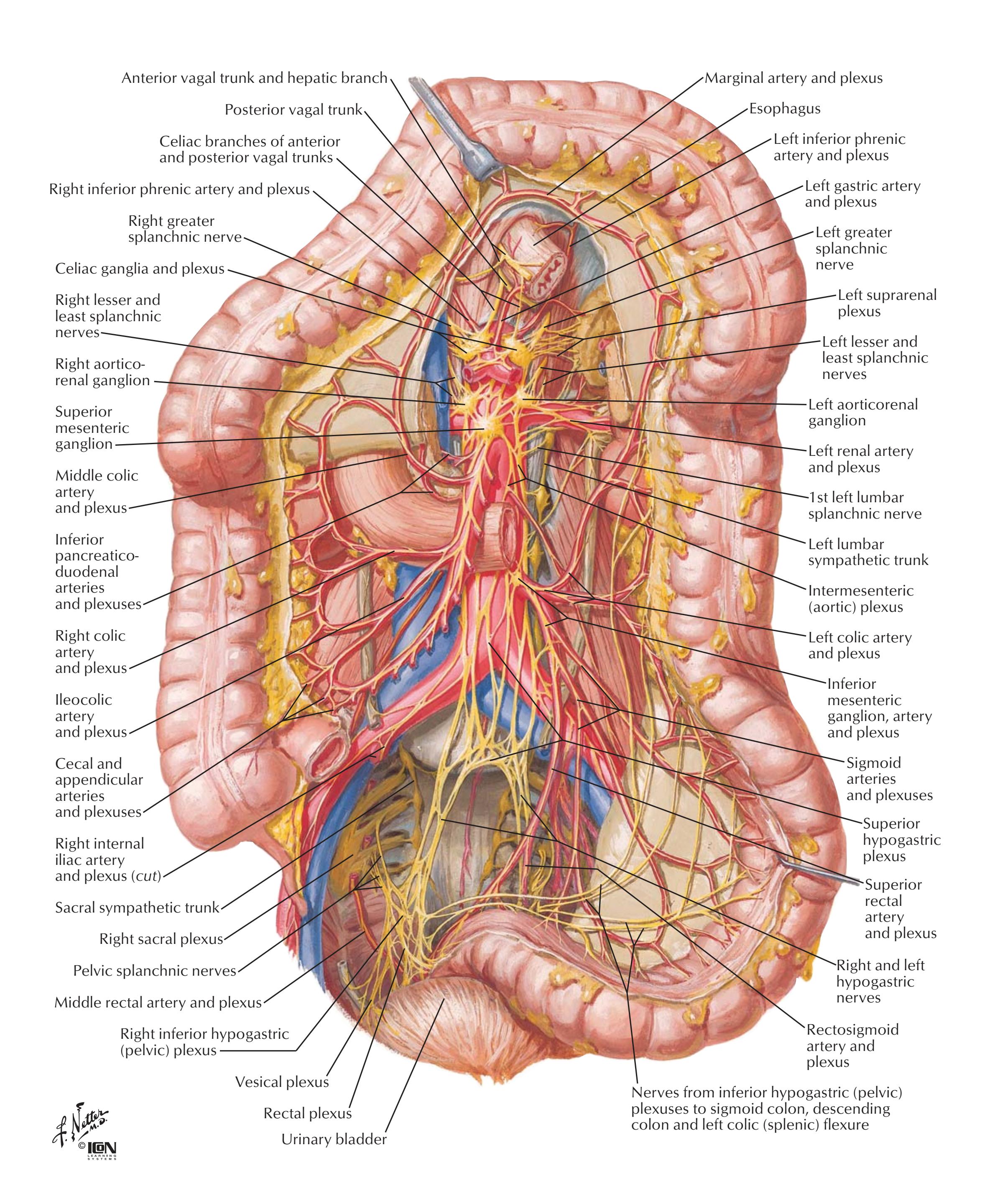

**NEUROANATOMY Nerves of Large Intestine**

**40**

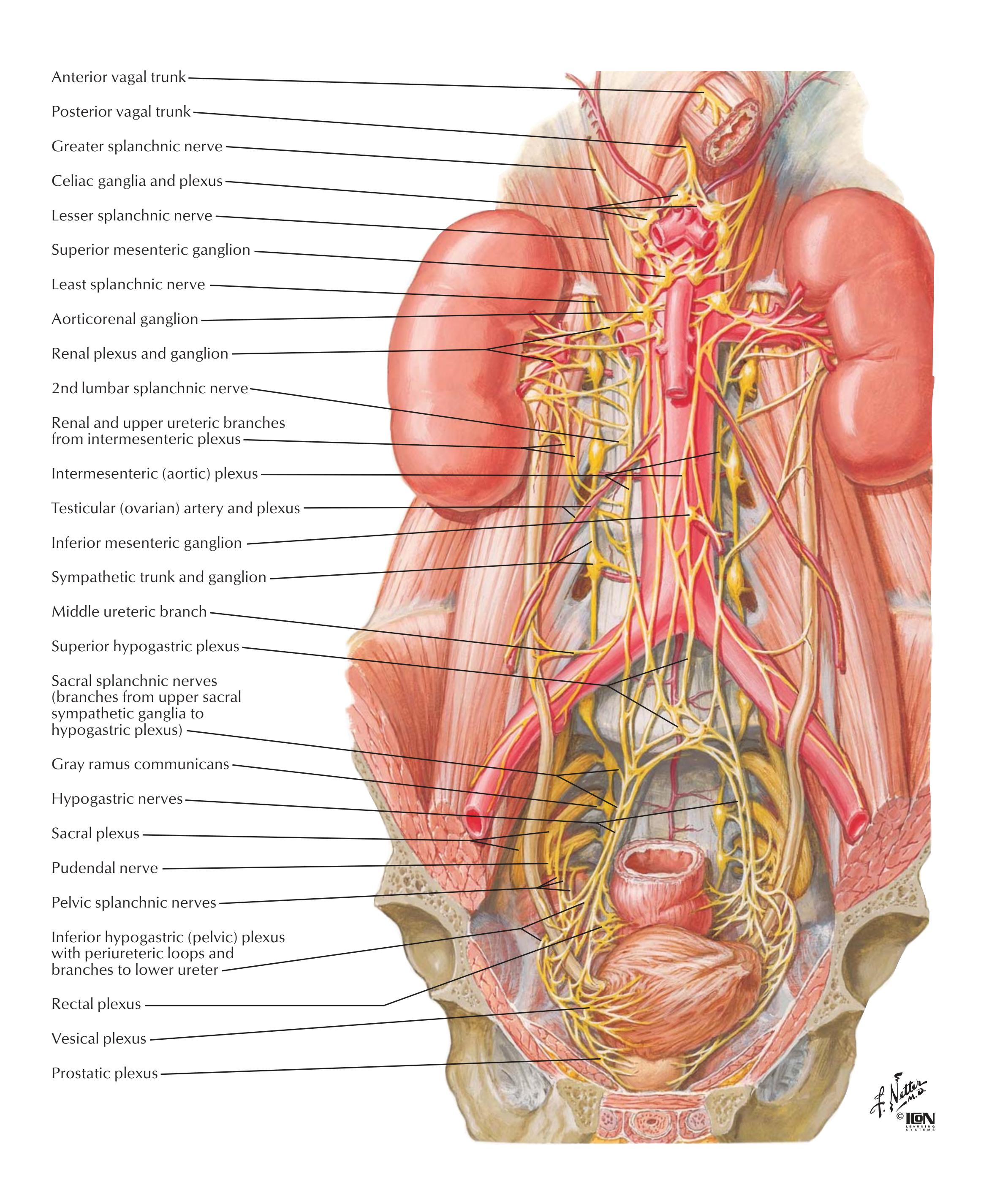

**Nerves of Kidneys, Ureters and Urinary Bladder NEUROANATOMY**

**41**

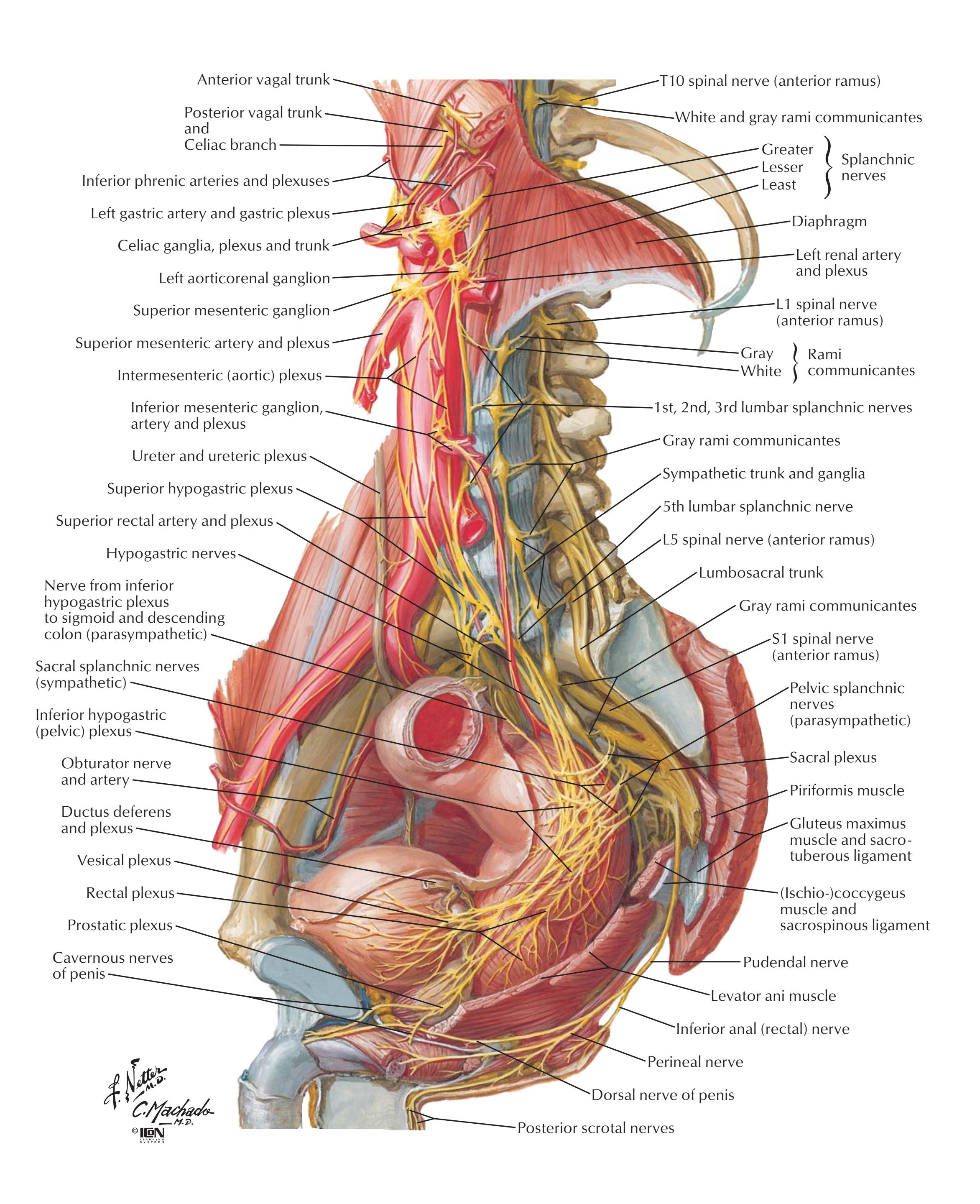

**NEUROANATOMY Nerves of Pelvic Viscera: Male**

**42**

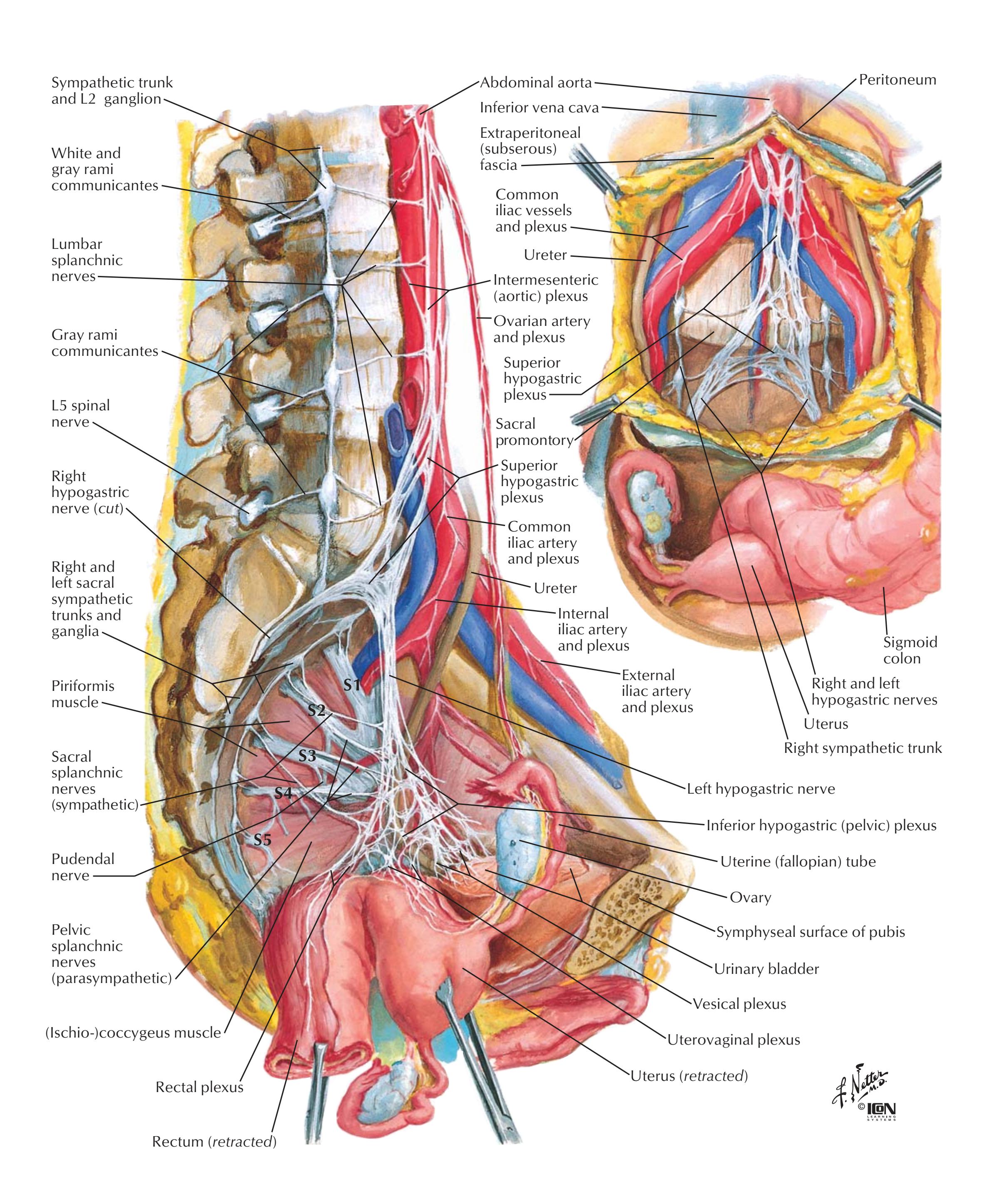

**Nerves of Pelvic Viscera: Female NEUROANATOMY**

**43**

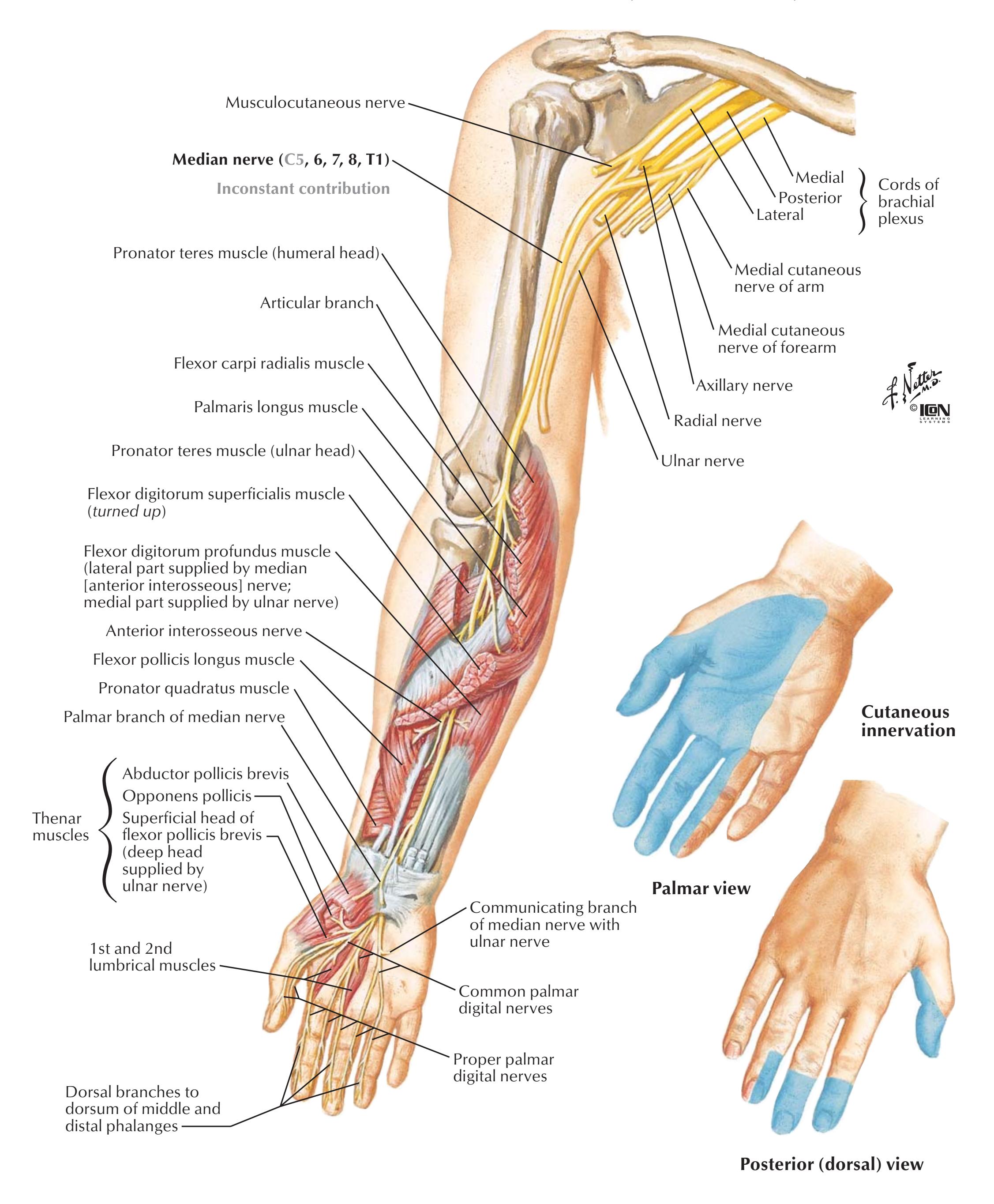

**NEUROANATOMY Median Nerve**

Anterior view Note: Only muscles innervated by median nerve shown

**44**

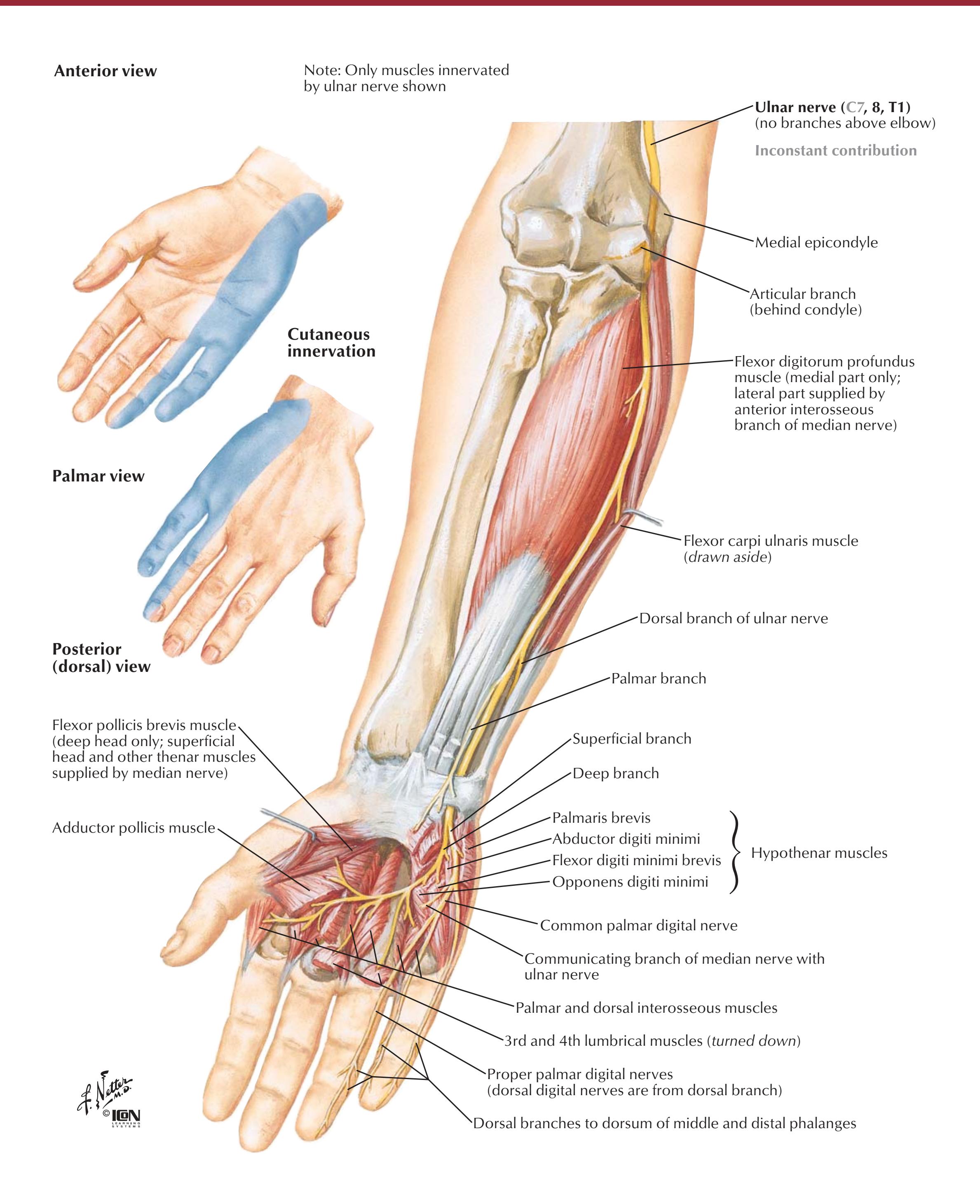

**Ulnar Nerve NEUROANATOMY**

**45**

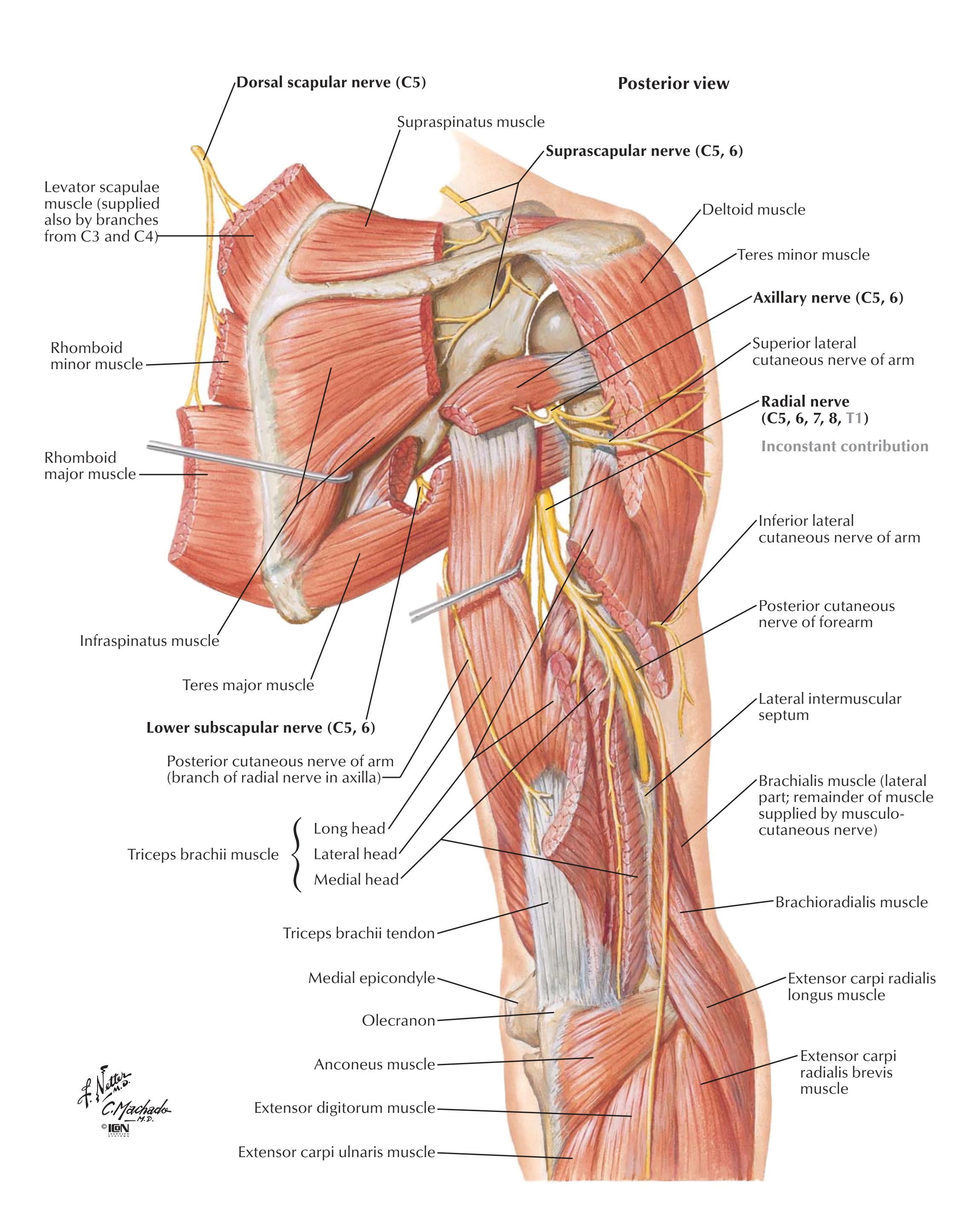

**NEUROANATOMY Radial Nerve in Arm and Nerves of Posterior Shoulder**

**46**

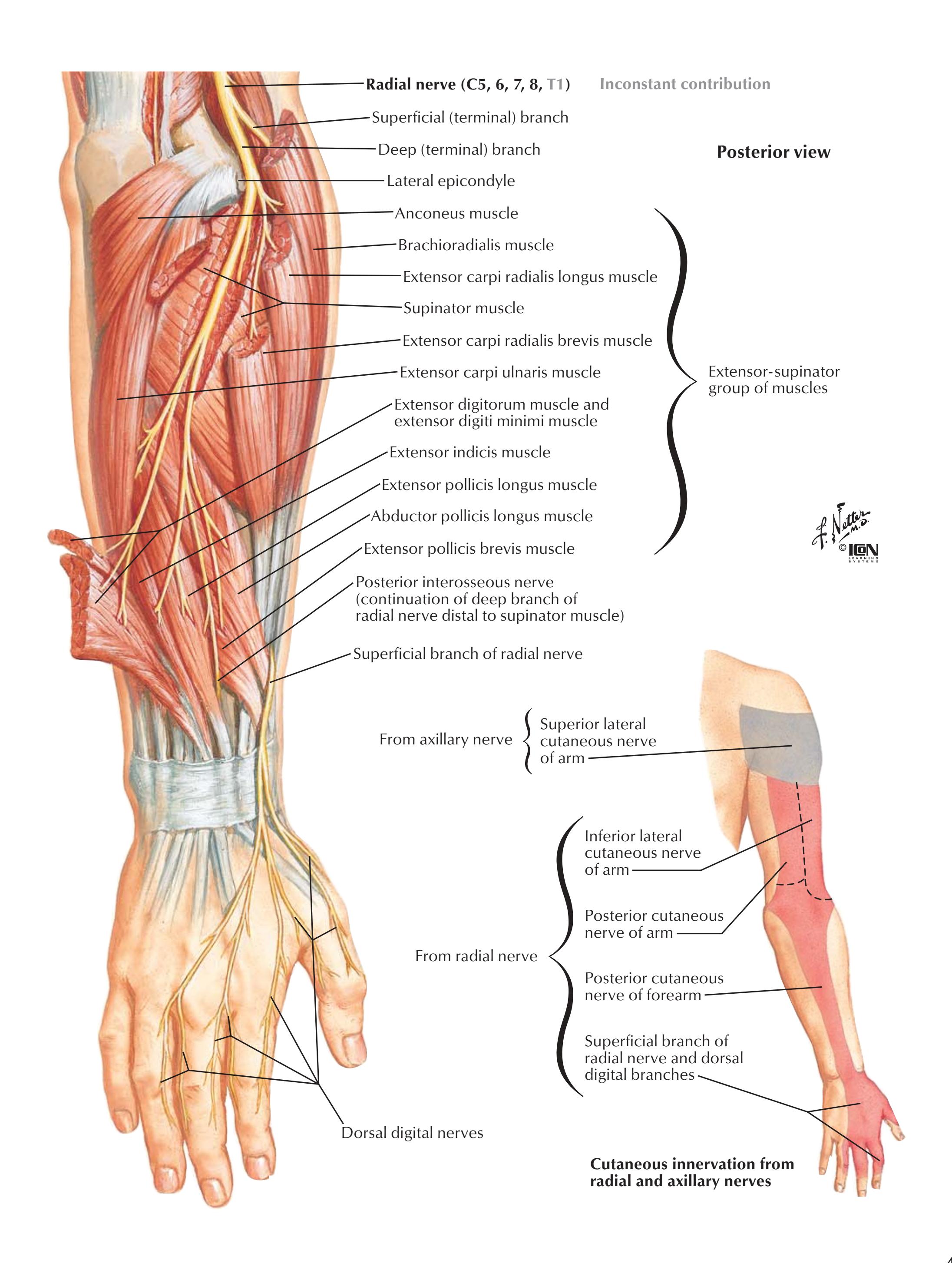

**Radial Nerve in Forearm NEUROANATOMY**

**47**

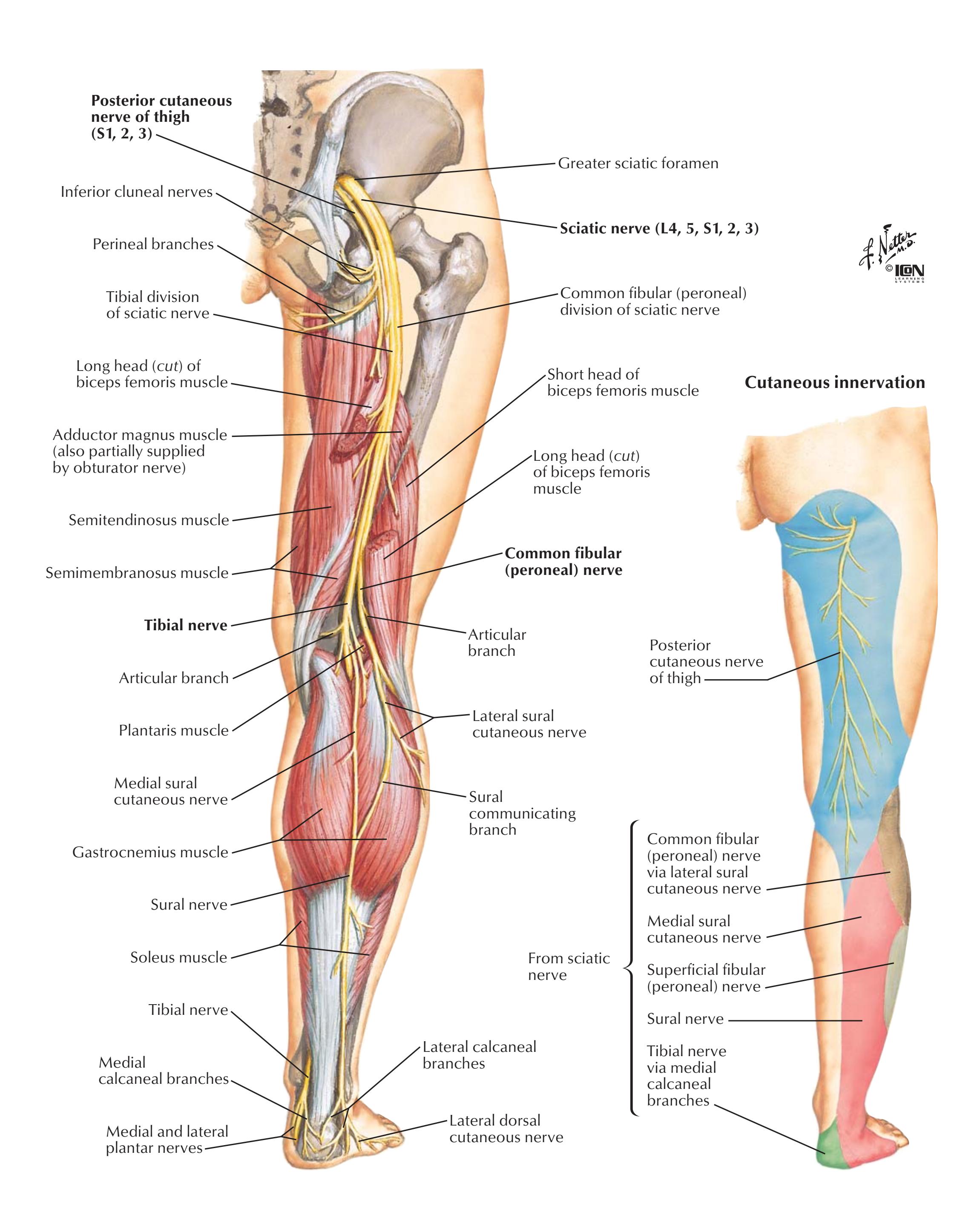

**NEUROANATOMY Sciatic Nerve and Posterior Cutaneous Nerve of Thigh**

**48**

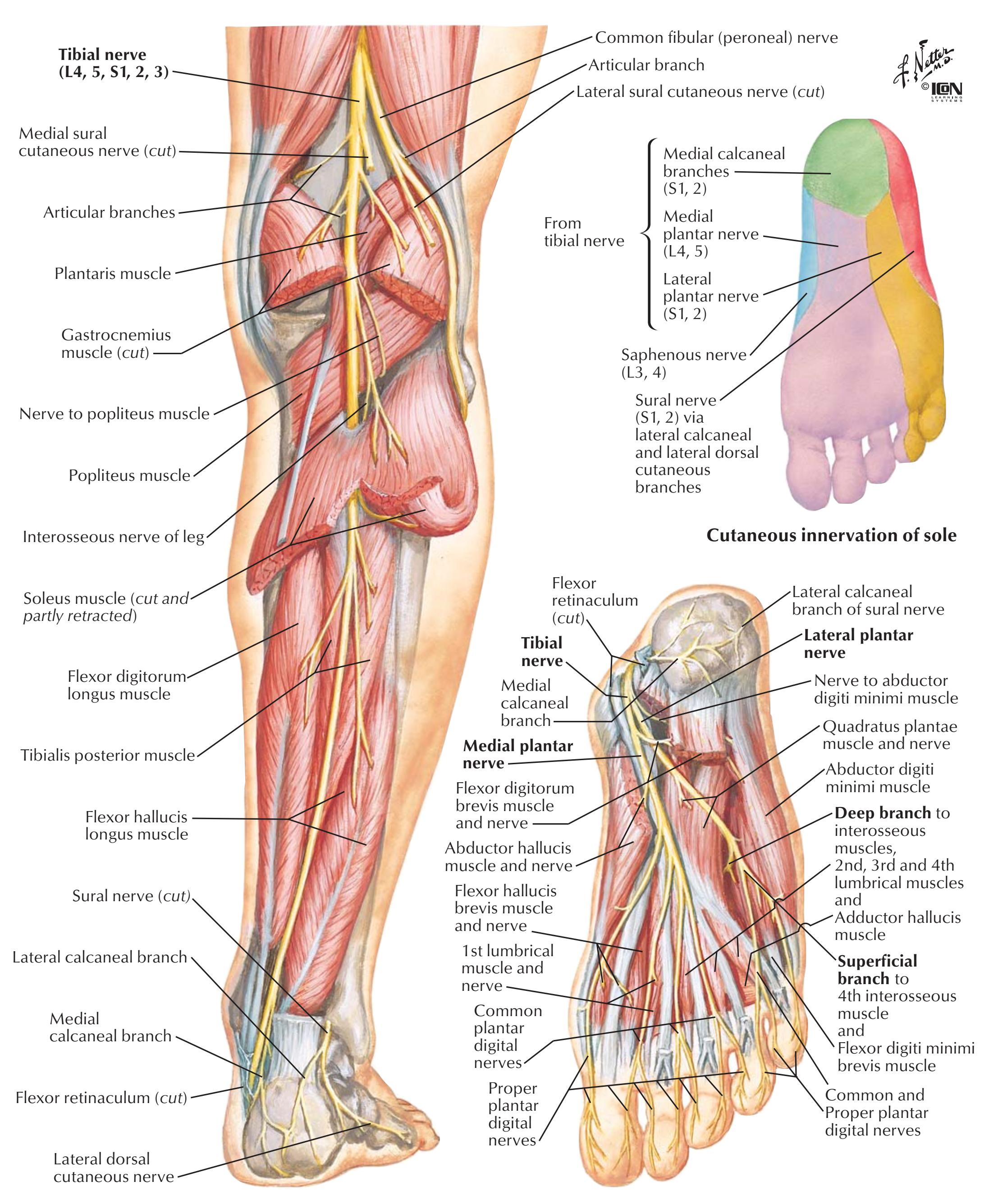

**Tibial Nerve NEUROANATOMY**

Note: Articular branches not shown

**49**

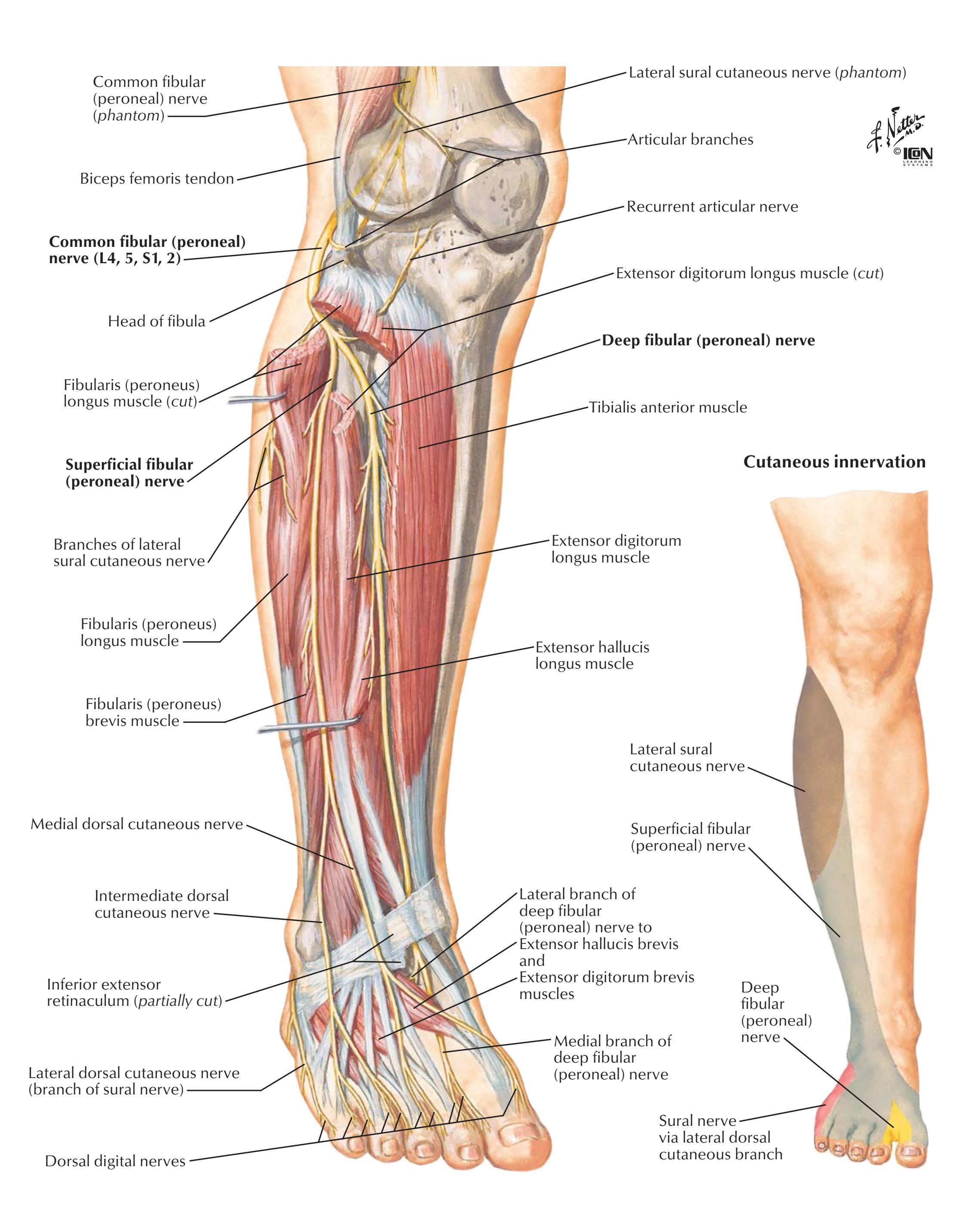

**NEUROANATOMY Common Fibular (Peroneal) Nerve**

**50**

## Click any title below to link to that plate.

# Part 2 Neurophysiology

| Chapter Title | Page Number |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------|-------------|

| Organization of the Brain: Cerebrum | 52 |

| Organization of the Brain: Cell Types | 53 |

| Blood-Brain Barrier | 54 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Morphology of Synapses | 55 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Neuromuscular Junction | 56 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Visceral Efferent Endings | 57 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Inhibitory Mechanisms | 58 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Chemical Synaptic Transmission | 59 |

| Synaptic Transmission: Temporal and Spatial Summation | 60 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Brain Ventricles and CSF Composition | 61 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Circulation of CSF | 62 |

| Spinal Cord: Ventral Rami | 63 |

| Spinal Cord: Membranes and Nerve Roots | 64 |

| Peripheral Nervous System | 65 |

| Autonomic Nervous System: Schema | 66 |

| Autonomic Nervous System: Cholinergic and Adrenergic Synapses | 67 |

| Hypothalamus | 68 |

| Limbic System | 69 |

| The Cerebral Cortex | 70 |

| Descending Motor Pathways | 71 |

| Cerebellum: Afferent Pathways | 72 |

| Cerebellum: Efferent Pathways | 73 |

| Cutaneous Sensory Receptors | 74 |

| Cutaneous Receptors: Pacinian Corpuscle | 75 |

| Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: I | 76 |

| Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: II | 77 |

| Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: III | 78 |

| Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: IV | 79 |

| Sensory Pathways: I | 80 |

| Sensory Pathways: II | 81 |

| Sensory Pathways: III | 82 |

| Visual System: Receptors | 83 |

| Visual System: Visual Pathway | 84 |

| Auditory System: Cochlea | 85 |

| Auditory System: Pathways | 86 |

| Vestibular System: Receptors | 87 |

| Vestibular System: Vestibulospinal Tracts | 88 |

| Gustatory (Taste) System: Receptors | 89 |

| Gustatory (Taste) System: Pathways | 90 |

| Olfactory System: Receptors | 91 |

| Olfactory System: Pathway | 92 |

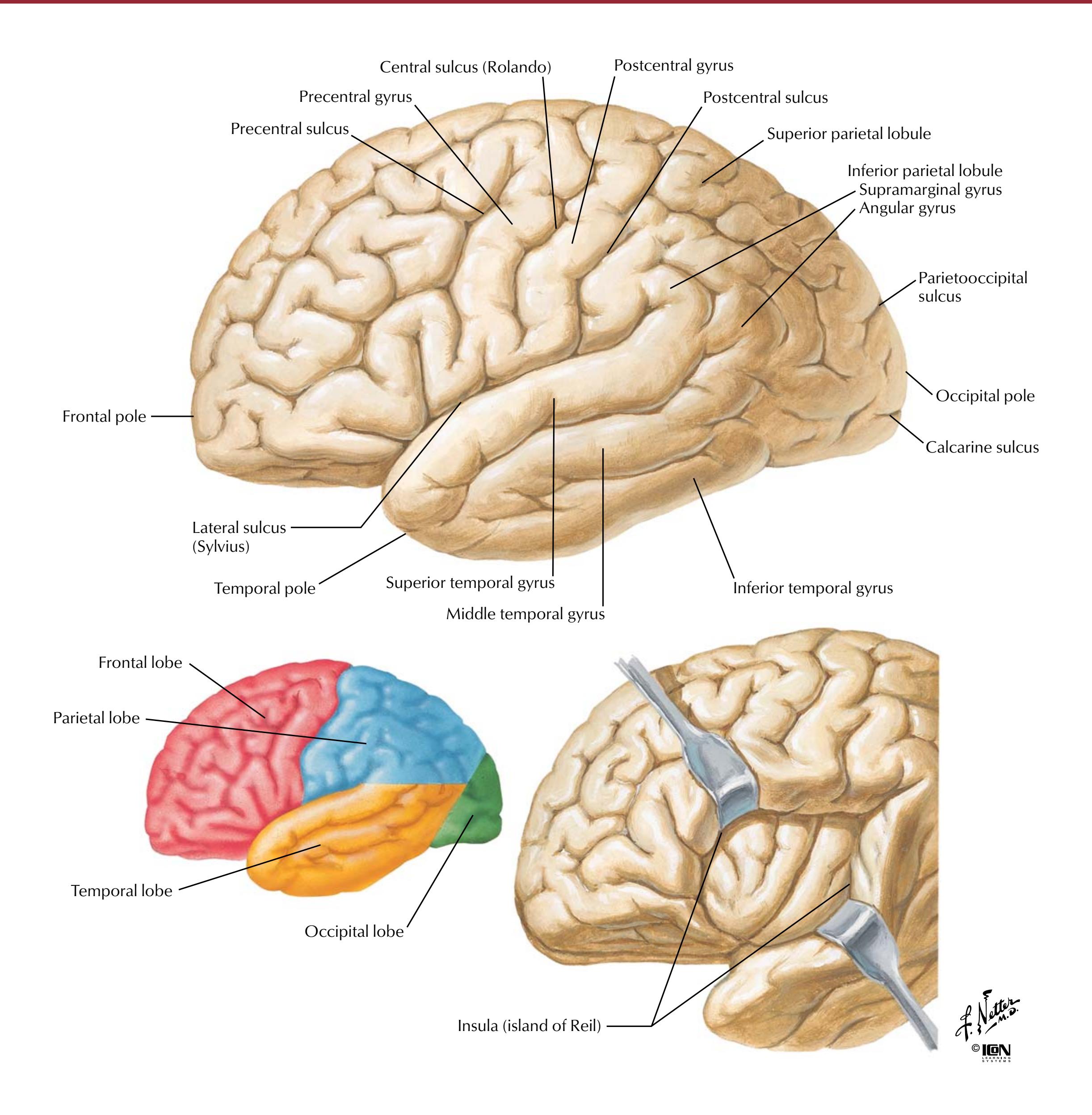

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Organization of the Brain: Cerebrum**

**FIGURE 2.1 ORGANIZATION OF THE BRAIN: CEREBRUM•**

The cerebral cortex represents the highest center for sensory and motor processing. In general, the frontal lobe processes motor, visual, speech, and personality modalities. The parietal lobe processes sensory information; the temporal lobe, auditory and memory modalities; and the occipital lobe, vision. The cerebellum coordinates smooth motor activities and processes muscle position. The brainstem (medulla, pons, midbrain) conveys motor and sensory information and mediates important autonomic functions. The spinal cord receives sensory input from the body and conveys somatic and autonomic motor information to peripheral targets (muscles, viscera).

**52**

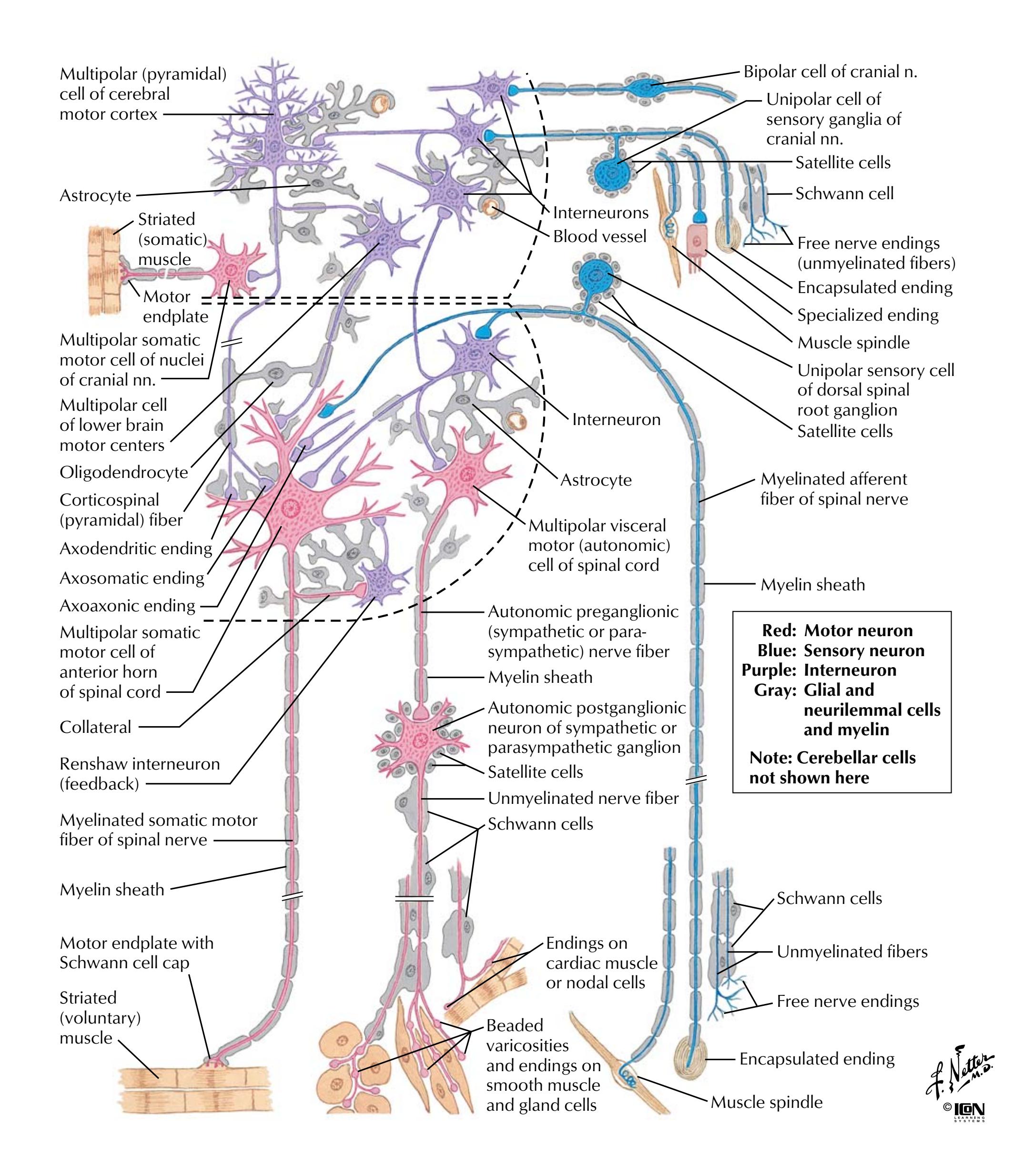

**Organization of the Brain: Cell Types NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**FIGURE 2.2 ORGANIZATION OF THE BRAIN: CELL TYPES•**

Neurons form the functional cellular units responsible for communication, and throughout the nervous system, they are characterized by their distinctive size and shapes (e.g., bipolar, unipolar, multipolar). Supporting cells include the neuroglia

(e.g., astrocytes, oligodendrocytes), satellite cells, and other specialized cells that optimize neuronal function, provide maintenance functions, or protect the nervous system.

**53**

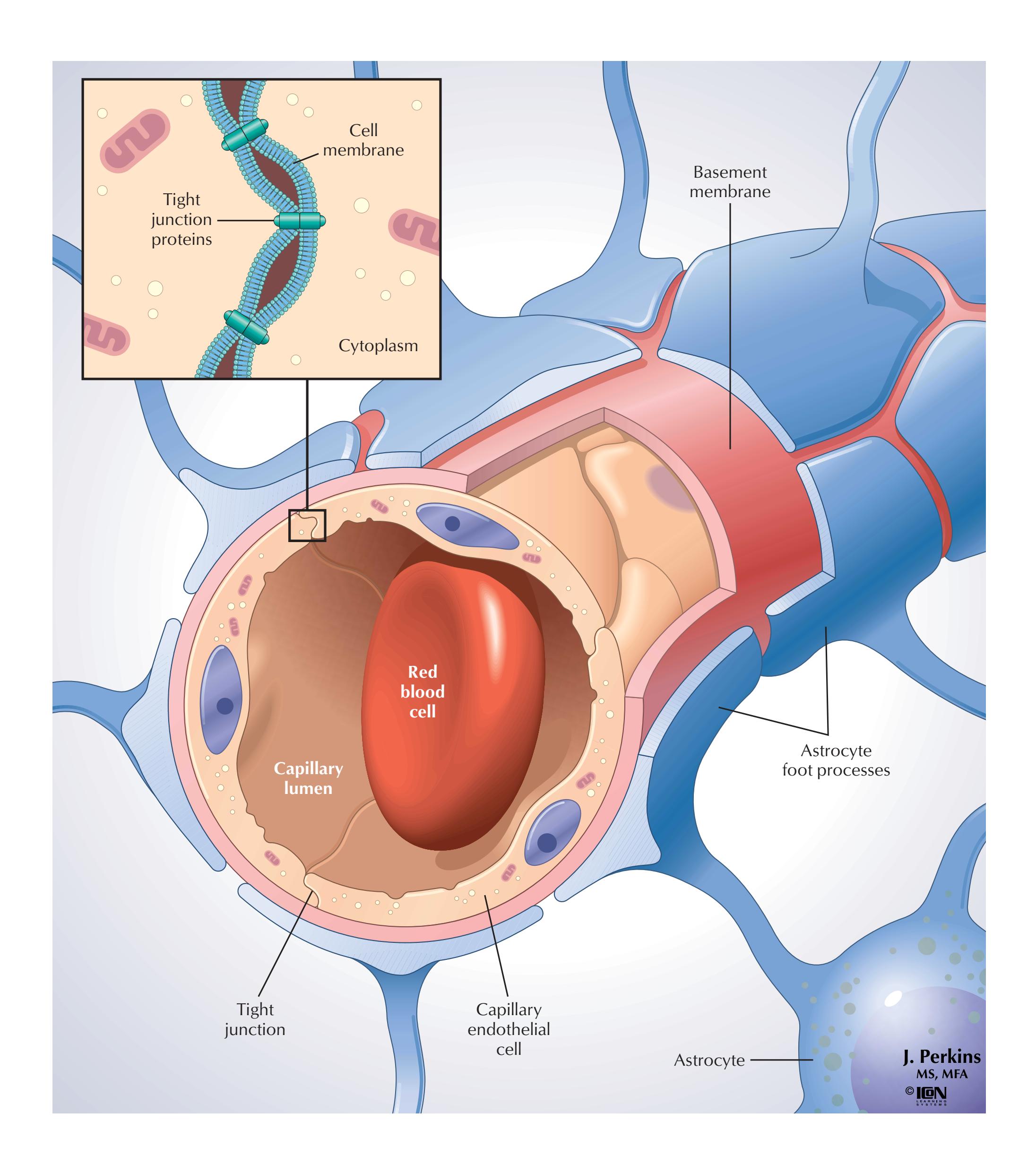

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Blood-Brain Barrier**

### FIGURE 2.3 BLOOD-BRAIN BARRIER

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is the cellular interface between the blood and the central nervous system (CNS; brain and spinal cord). It serves to maintain the interstitial fluid environment to ensure optimal functionality of the neurons. This barrier consists of the capillary endothelial cells with an elaborate network of tight junctions and astrocytic foot processes that abut the endothelium and its basement membrane. The movement of large molecules and

other substances (including many drugs) from the blood to the interstitial space of the CNS is restricted by the BBB. CNS endothelial cells also exhibit a low level of pinocytotic activity across the cell, so specific carrier systems for the transport of essential substrates of energy and amino acid metabolism are characteristic of these cells. The astrocytes help transfer important metabolites from the blood to the neurons and also remove excess K and neurotransmitters from the interstitial fluid.

**54**

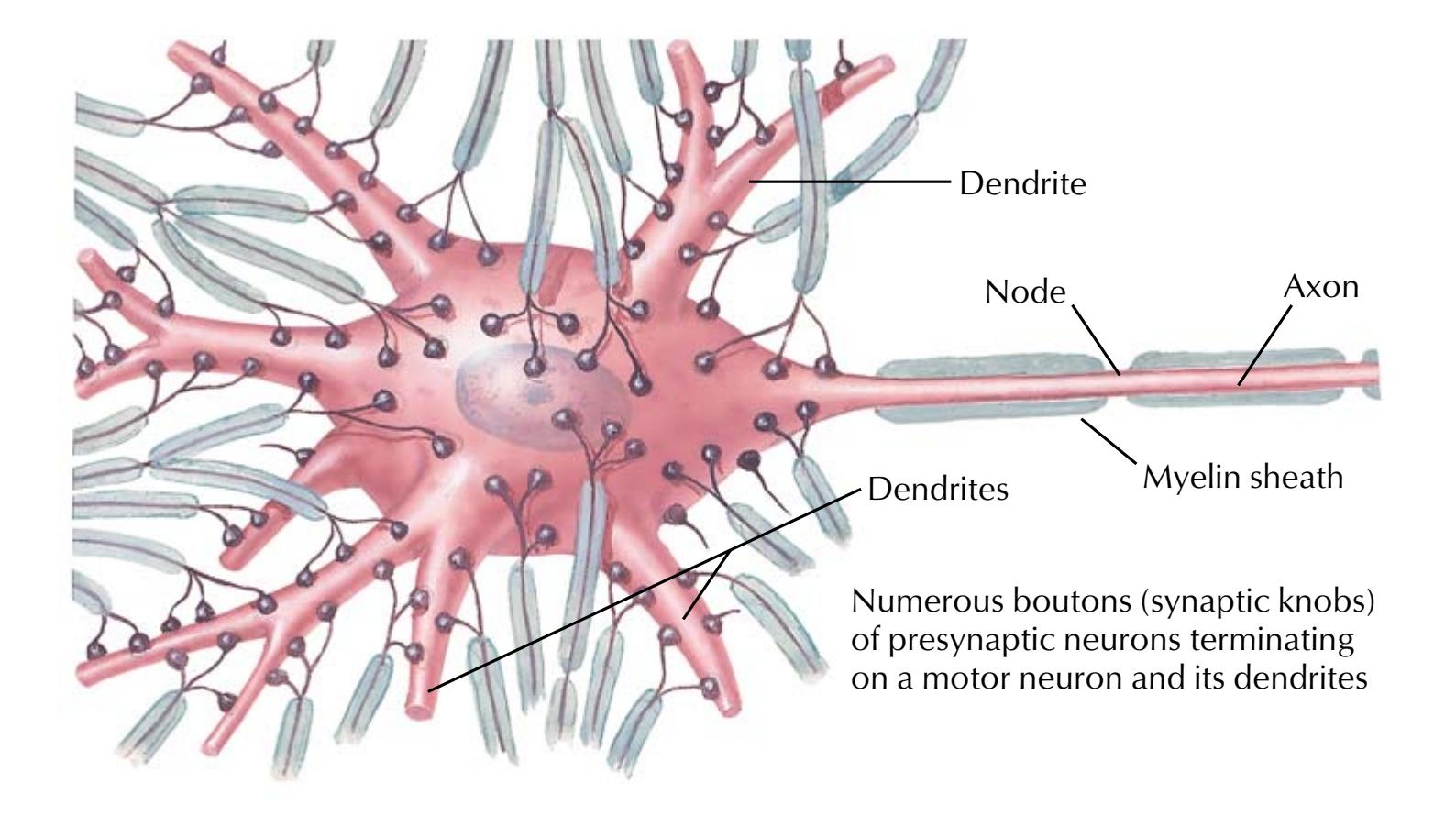

**Synaptic Transmission: Morphology of Synapses NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

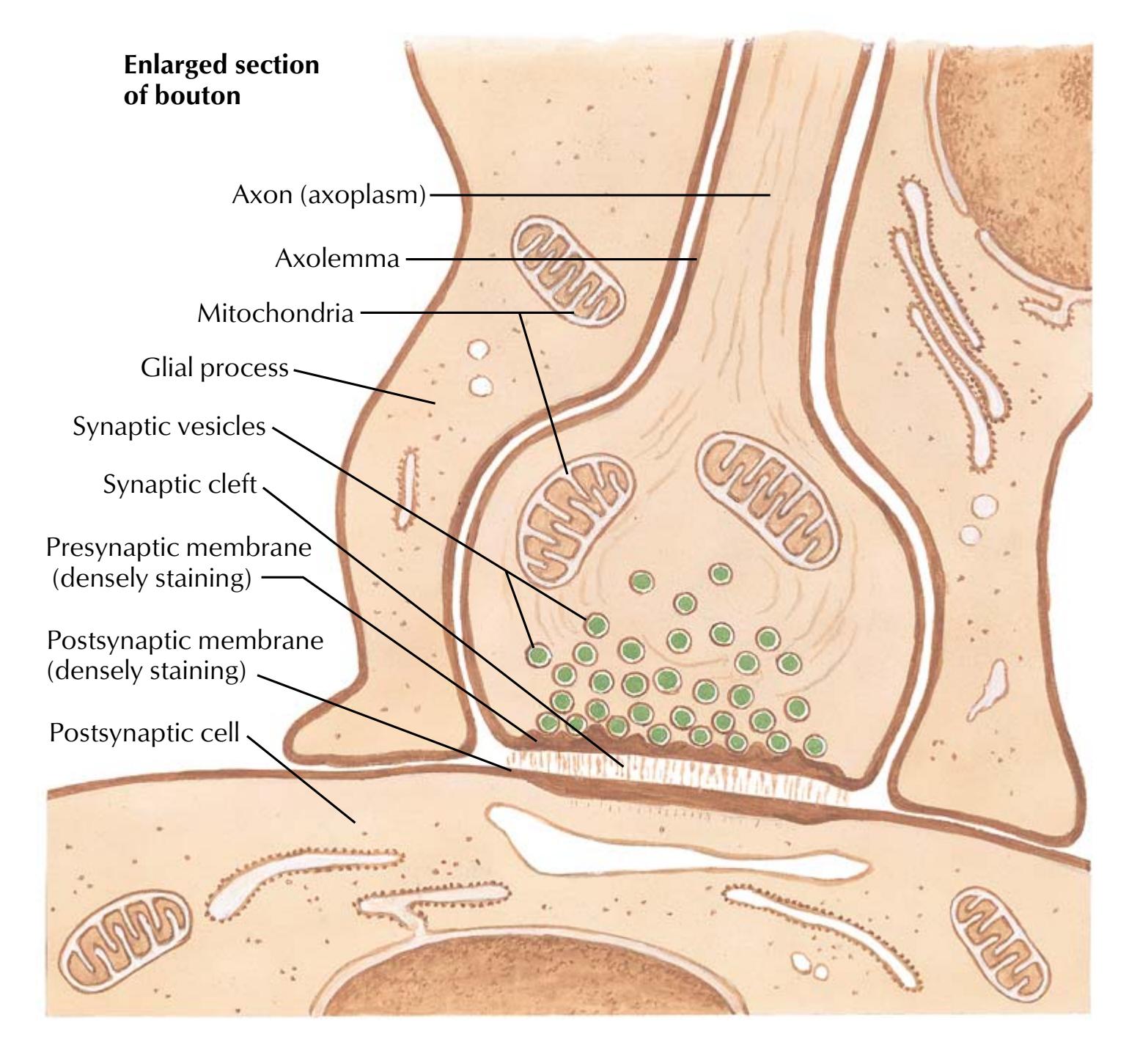

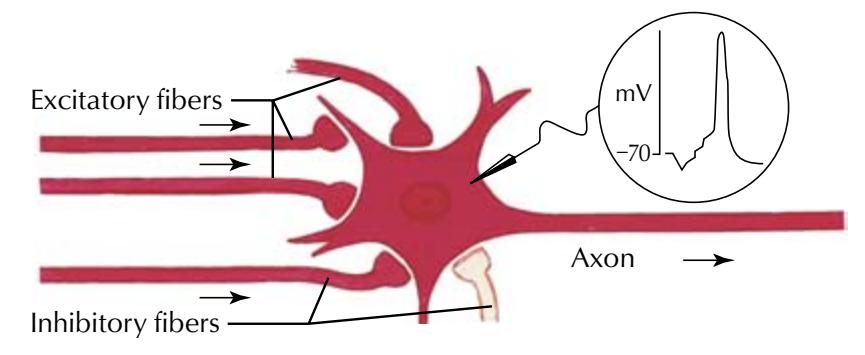

### FIGURE 2.4 MORPHOLOGY OF SYNAPSES

Neurons communicate with each other and with effector targets at specialized regions called synapses. The top figure shows a typical motor neuron that receives numerous synaptic contacts on its cell body and associated dendrites. Incoming axons lose their myelin sheaths, exhibit extensive branching, and terminate as synaptic boutons (synaptic terminals or knobs) on the motor neuron. The

lower figure shows an enlargement of one such synaptic bouton. Chemical neurotransmitters are contained in synaptic vesicles, which can fuse with the presynaptic membrane, release the transmitters into the synaptic cleft, and then bind to receptors situated in the postsynaptic membrane. This synaptic transmission results in excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory effects on the target cell.

**55**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Synaptic Transmission: Neuromuscular Junction**

### FIGURE 2.5 STRUCTURE OF THE NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION

Motor axons that synapse on skeletal muscle form expanded terminals called neuromuscular junctions (motor endplates). The motor axon loses its myelin sheath and expands into a Schwann cell–invested synaptic terminal that resides within a trough in the muscle fiber. Acetylcholine-containing synaptic vesicles accumulate adjacent to the presynaptic membrane and, when appropriately stimulated, release their neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft. The transmitter then binds to receptors that mediate depolarization of the muscle sarcolemma and initiate a muscle action potential. A single muscle fiber has only one neuromuscular junction, but a motor axon can innervate multiple muscle fibers.

**56**

**Synaptic Transmission: Visceral Efferent Endings NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

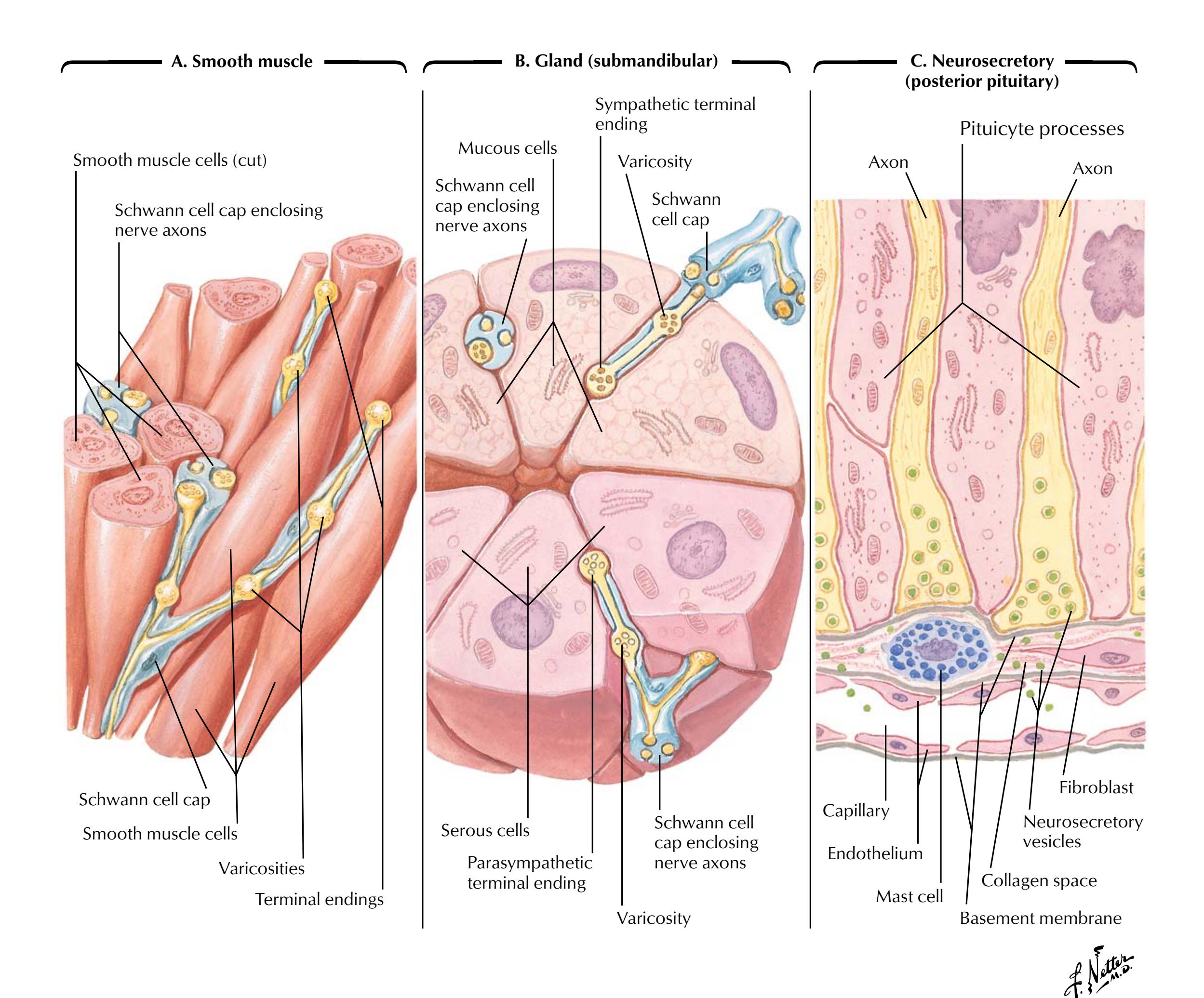

### FIGURE 2.6 VISCERAL EFFERENT ENDINGS

Neuronal efferent endings on smooth muscle (A) and glands (B and C) exhibit unique endings unlike the presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals observed in neuronal and neuromuscular junction synapses. Rather, neurotransmitter substances are released into interstitial spaces (A and B) or into the bloodstream (C, neurosecretion) from expanded nerve terminal endings. This arrangement allows for the stimulation of numerous target cells over a wide area. Not all smooth muscle cells are innervated. They are connected to adjacent cells by gap junctions and can therefore contract together with the innervated cells.

**57**

©

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Synaptic Transmission: Inhibitory Mechanisms**

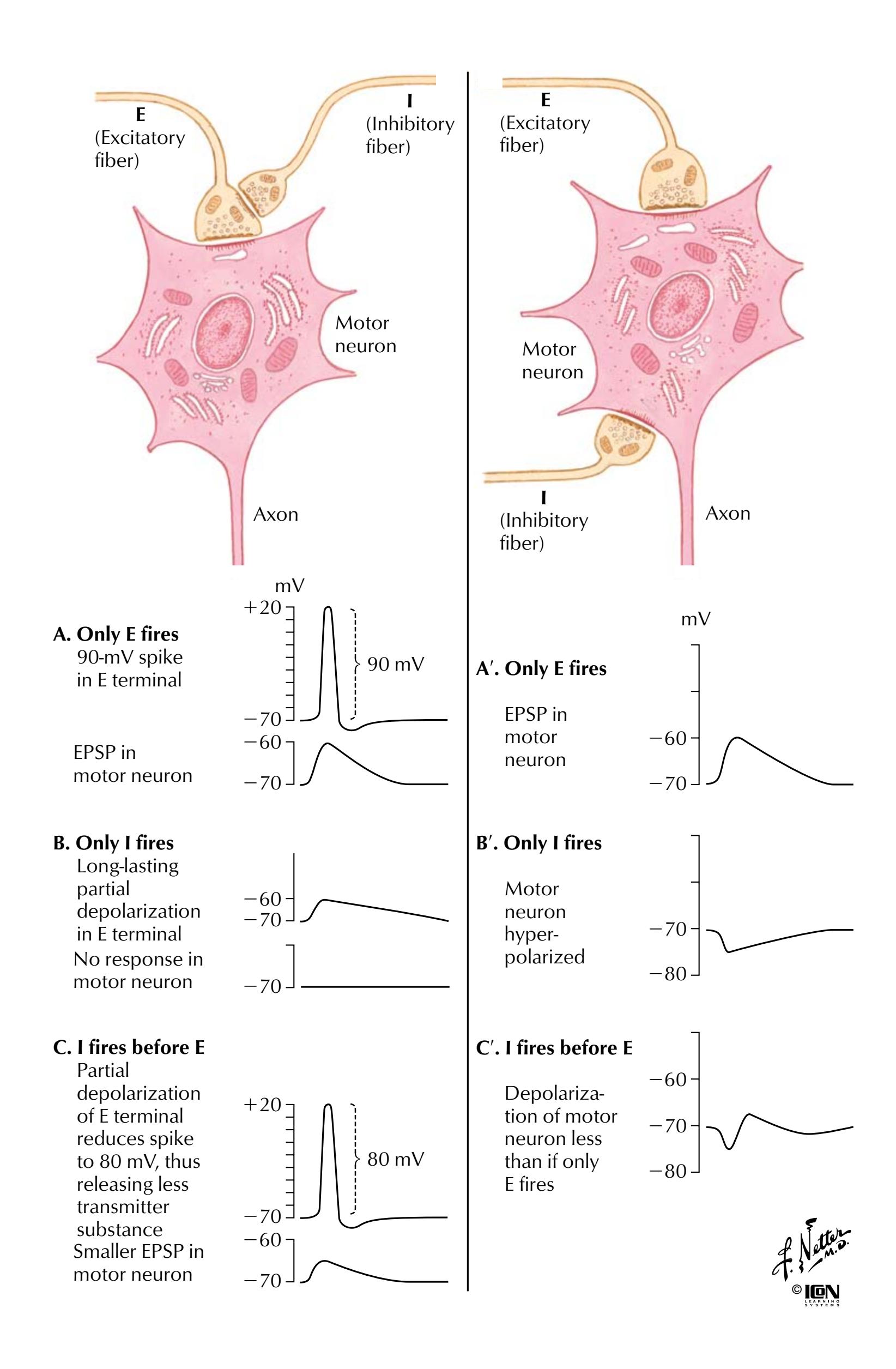

**FIGURE 2.7 SYNAPTIC INHIBITORY MECHANISMS•**

Inhibitory synapses modulate neuronal activity. Illustrated here is presynaptic inhibition (left panel) and postsynaptic inhibition (right panel) at a motor neuron.

**58**

**Synaptic Transmission: Chemical Synaptic Transmission NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

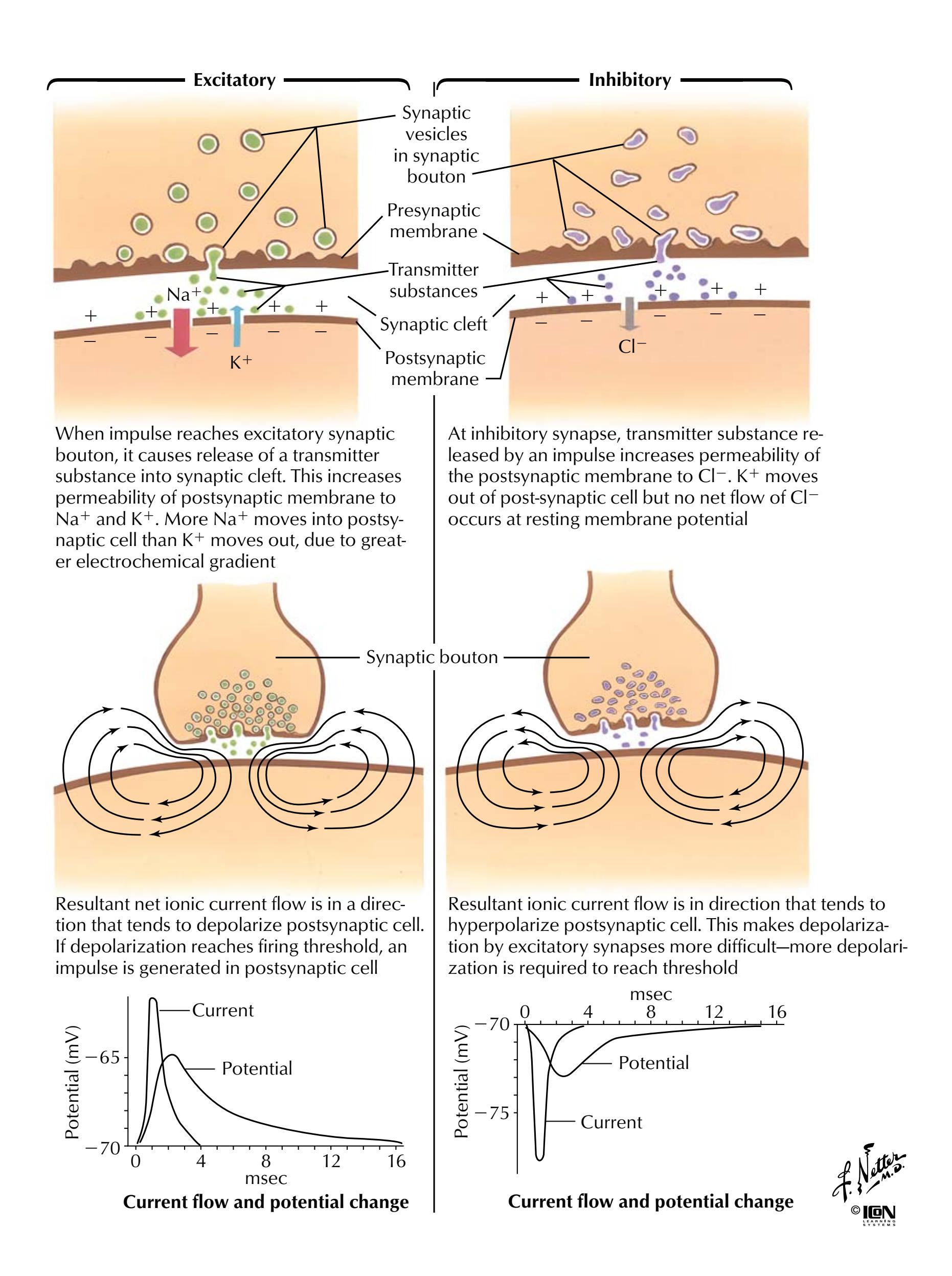

### FIGURE 2.8 CHEMICAL SYNAPTIC TRANSMISSION

Chemical synaptic transmission between neurons may be excitatory or inhibitory. During excitation (left column), a net increase in the inward flow of Na compared with the outward flow of K results in a depolarizing potential change (excitatory postsynaptic potential [EPSP]) that drives the postsynaptic cell closer to its

threshold for an action potential. During inhibition (right column), the opening of K and Cl channels drives the membrane potential away from threshold (hyperpolarization) and decreases the probability that the neuron will reach threshold (inhibitory postsynaptic potential [IPSP]) for an action potential.

**59**

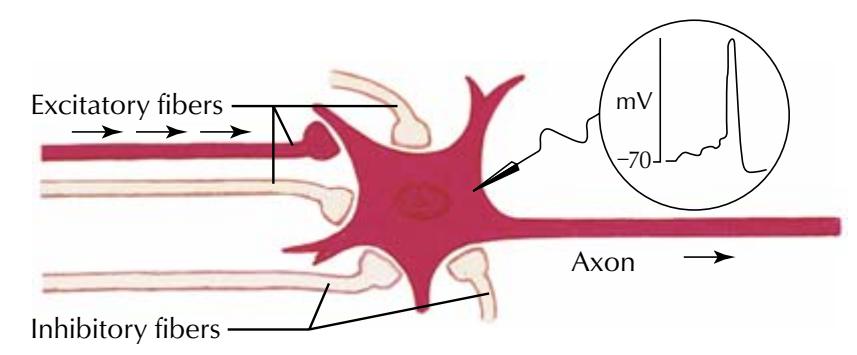

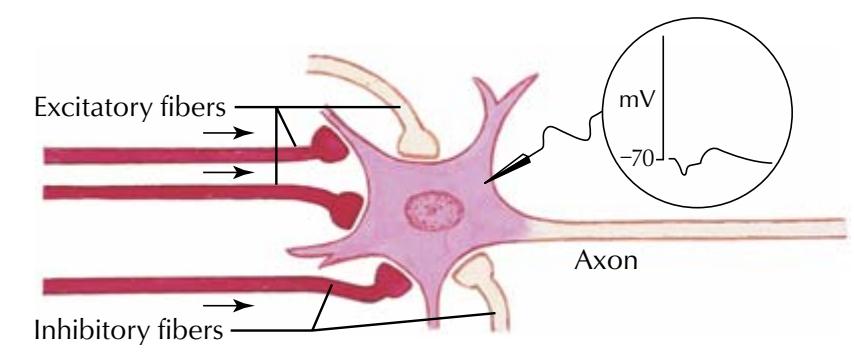

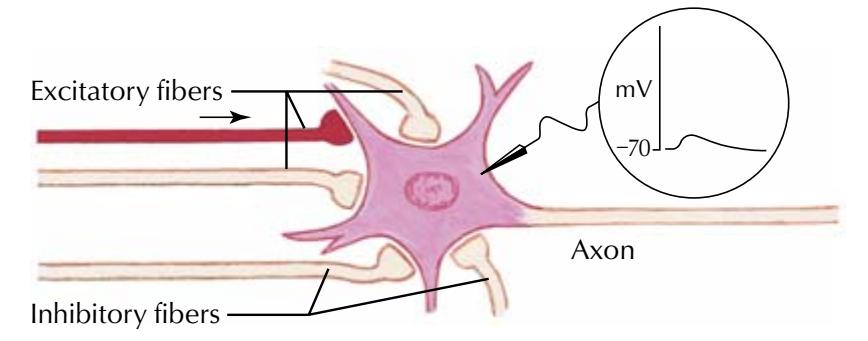

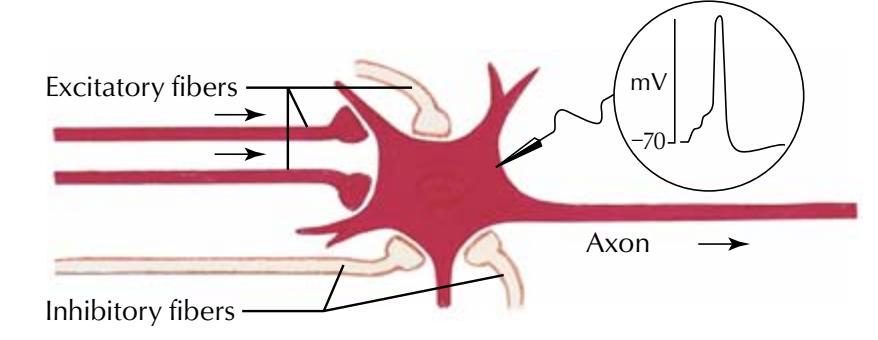

## NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Synaptic Transmission: Temporal and Spatial Summation

A. Resting state: motor nerve cell shown with synaptic boutons of excitatory and inhibitory nerve fibers ending close to it

C. Temporal excitatory summation: a series of impulses in one excitatory fiber together produce a suprathreshold depolarization that triggers an action potential

E. Spatial excitatory summation with inhibition: impulses from two excitatory fibers reach motor neuron but impulses from inhibitory fiber prevent depolarization from reaching threshold

B. Partial depolarization: impulse from one excitatory fiber has caused partial (below firing threshold) depolarization of motor neuron

D. Spatial excitatory summation: impulses in two excitatory fibers cause two synaptic depolarizations that together reach firing threshold triggering an action potential

E. (continued): motor neuron now receives additional excitatory impulses and reaches firing threshold despite a simultaneous inhibitory impulse; additional inhibitory impulses might still prevent firing

### CHART 2.1 SUMMARY OF SOME NEUROTRANSMITTERS AND WHERE WITHIN THE CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEM THEY ARE FOUND

| Transmitter | Location | Transmitter | Location |

|------------------------------------------------------------|------------------------------------------------------------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Acetylcholine | Neuromuscular junction, autonomic endings and ganglia, CNS | Gas

Nitric oxide | CNS, GI tract |

| Biogenic amines

Norepinephrine

Dopamine

Serotonin | Sympathetic endings, CNS

CNS

CNS, GI tract | Peptides

β-Endorphins

Enkephalins

Antidiuretic

hormone

Pituitary-releasing

hormones

Somatostatin

Neuropeptide Y

Vasoactive

intestinal peptide | CNS, GI tract

CNS

CNS (hypothalamus/posterior

pituitary)

CNS (hypothalamus/anterior

pituitary)

CNS, GI tract

CNS

CNS, GI tract |

| Amino acids

γ-Aminobutyric

acid (GABA)

Glutamate | CNS

CNS | | |

| Purines

Adenosine

Adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) | CNS

CNS | | |

*CNS,* Central nervous system; *GI,* gastrointestinal.

### FIGURE 2.9 TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL SUMMATION

Neurons receive multiple excitatory and inhibitory inputs. Temporal summation occurs when a series of subthreshold impulses in one excitatory fiber produces an action potential in the postsynaptic cell (panel C). Spatial summation occurs when subthreshold impulses from two or more different fibers trigger an action potential (panel D). Both temporal and spatial summation can be modulated by simultaneous inhibitory input (panel E). Inhibitory and excitatory neurons use a wide variety of neurotransmitters, some of which are summarized here.

**60**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Brain Ventricles and CSF Composition**

**CHART 2.2 CSF COMPOSITION**

| | CSF | Blood Plasma |

|-----------------|-----------|--------------|

| Na+ (mEq/L) | 140–145 | 135–147 |

| K+ (mEq/L) | 3 | 3.5–5.0 |

| Cl- (mEq/L) | 115–120 | 95–105 |

| HCO3- (mEq/L) | 20 | 22–28 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 50–75 | 70–110 |

| Protein (g/dL) | 0.05–0.07 | 6.0–7.8 |

| pH | 7.3 | 7.35–7.45 |

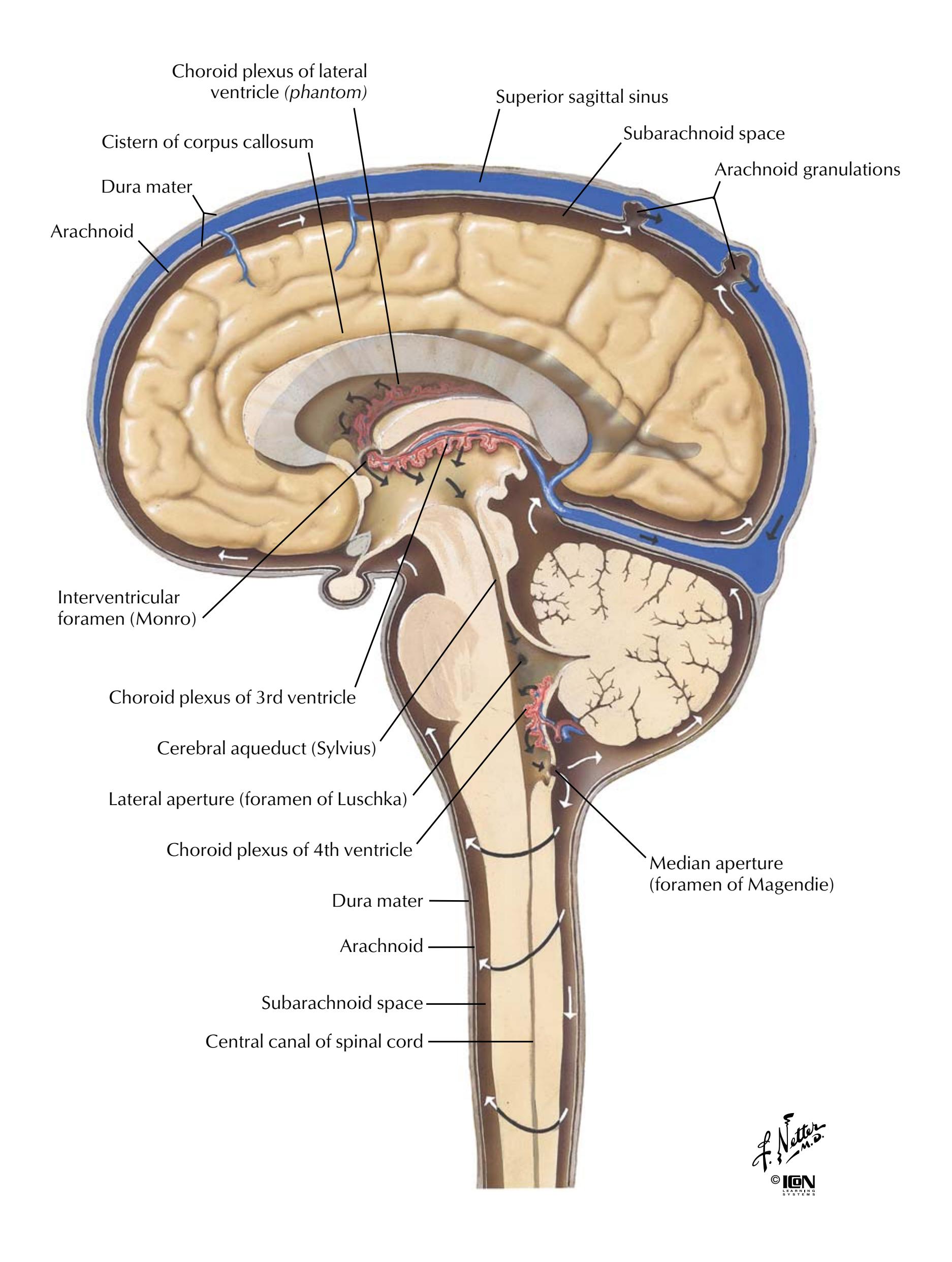

### FIGURE 2.10 BRAIN VENTRICLES AND CSF COMPOSITION

CSF circulates through the four brain ventricles (two lateral ventricles and a third and fourth ventricle) and in the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain and spinal cord. The electrolyte composition of the CSF is regulated by the choroid plexus, which

secretes the CSF. Importantly, the CSF has a lower $[HCO_3^-]$ than plasma and therefore a lower pH. This allows small changes in blood $PCO_2$ to cause changes in CSF pH, which in turn regulates the rate of respiration (see Chapter 5).**61**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Circulation of CSF**

### FIGURE 2.11 CIRCULATION OF CEREBROSPINAL FLUID

CSF circulates through the four brain ventricles (two lateral ventricles and a third and fourth ventricle) and in the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Most of the CSF is

reabsorbed into the venous system through the arachnoid granulations and through the walls of the capillaries of the central nervous system and pia mater.

**62**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Spinal Cord: Ventral Rami**

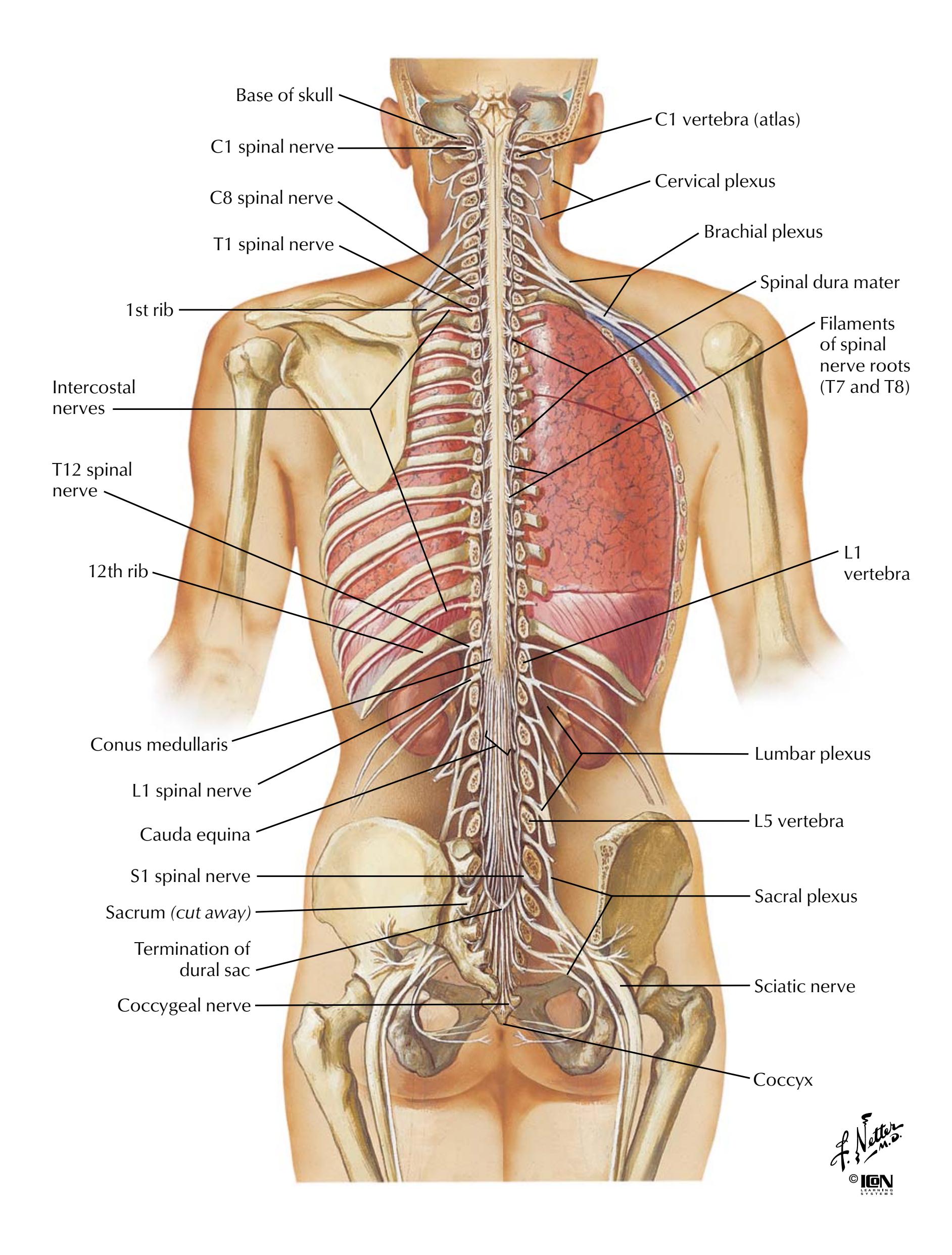

**FIGURE 2.12 SPINAL CORD AND VENTRAL RAMI IN SITU•**

The spinal cord gives rise to 31 pairs of spinal nerves that distribute segmentally to the body. These nerves are organized into plexuses that distribute to the neck (cervical plexus), upper limb (brachial plexus), and pelvis and lower limb (lumbosacral plexus). Motor

fibers of these spinal nerves innervate skeletal muscle, and sensory fibers convey information back to the central nervous system from the skin, skeletal muscles, and joints.

**63**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Spinal Cord: Membranes and Nerve Roots**

### FIGURE 2.13 SPINAL MEMBRANES AND NERVE ROOTS

The spinal cord gives rise to 31 pairs of spinal nerves that distribute segmentally to the body. Motor fibers of these spinal nerves innervate skeletal muscle, and sensory fibers convey information back to the central nervous system from the skin, skeletal muscles, and joints.

The spinal cord is ensheathed in three meningeal coverings: the outer, tough dura mater; the arachnoid mater; and the pia mater, which intimately ensheaths the cord itself. CSF bathes the cord and is found in the subarachnoid space.

**64**

**Peripheral Nervous System NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

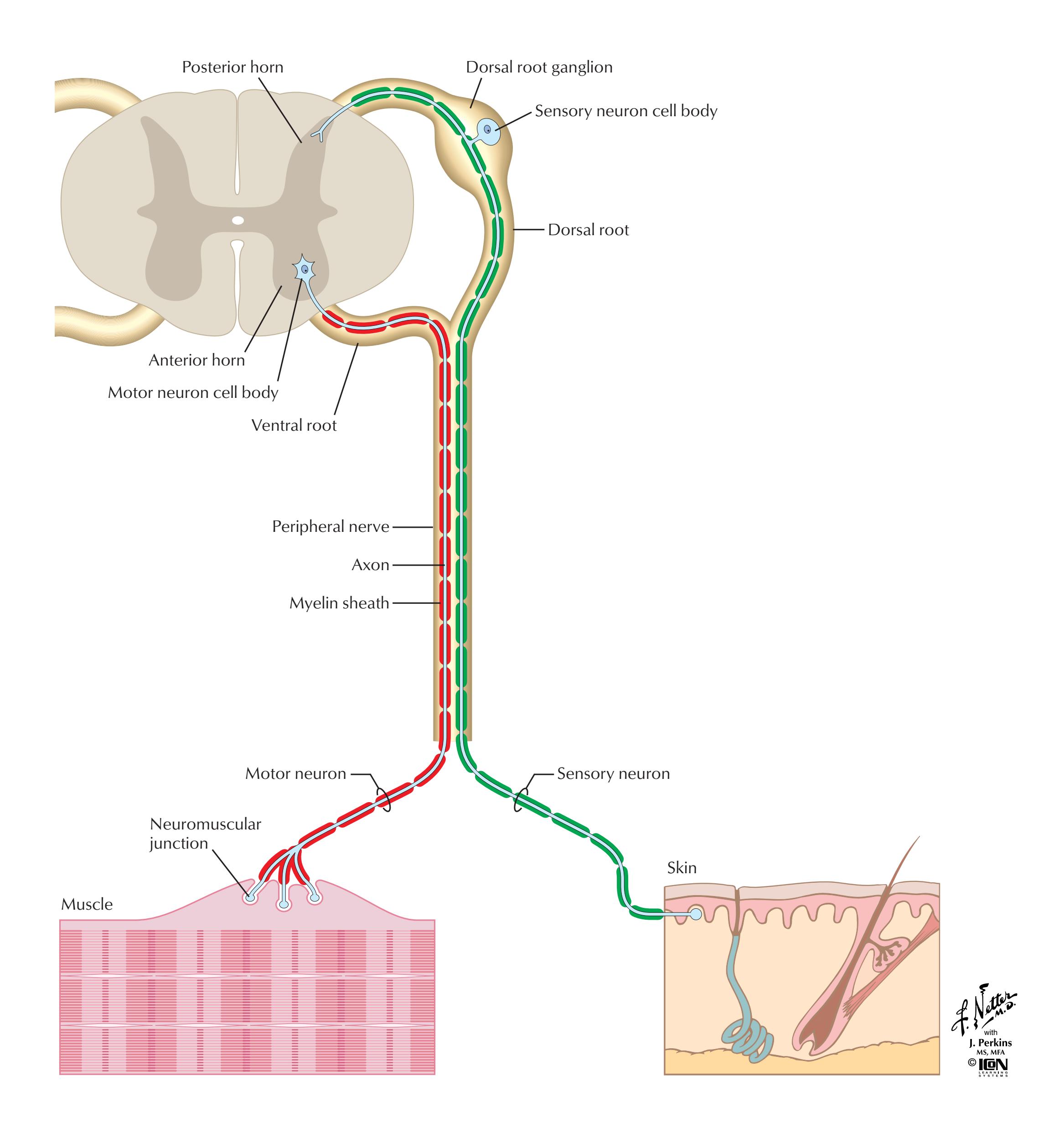

### FIGURE 2.14 PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all of the neural elements outside of the CNS (brain and spinal cord) and provides the connections between the CNS and all other body organ systems. The PNS consists of somatic and autonomic components. The somatic component innervates skeletal muscle and skin and is

shown here (see Figure 2.15 for the autonomic nervous system). The somatic component of the peripheral nerves contains both motor and sensory axons. Cell bodies of the motor neurons are found in the anterior horn gray matter, whereas the cell bodies of sensory neurons are located in the dorsal root ganglia.

**65**

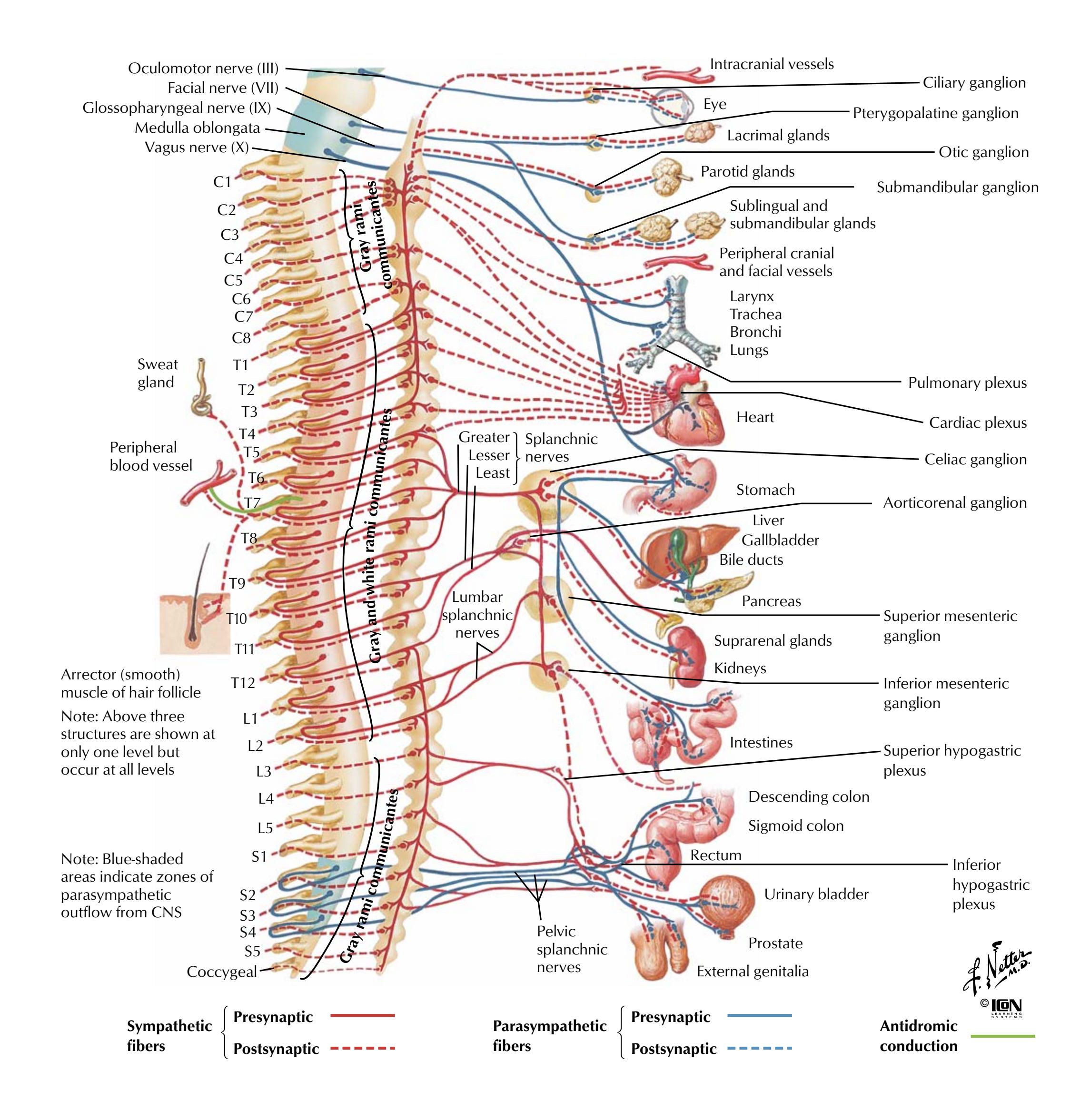

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Autonomic Nervous System: Schema**

### FIGURE 2.15 AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM: SCHEMA

The autonomic nervous system is composed of two divisions: the parasympathetic division derived from four of the cranial nerves (CN III, VII, IX, and X) and the S2-S4 sacral spinal cord levels, and the sympathetic division associated with the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord levels (T1-L2). The autonomic nervous system is a twoneuron chain, with the preganglionic neuron arising from the central nervous system and synapsing on a postganglionic neuron located in

a peripheral autonomic ganglion. Postganglionic axons of the autonomic nervous system innervate smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands. Basically, the sympathetic division mobilizes our body ("fight or flight") while the parasympathetic division regulates digestive and homeostatic functions. Normally, both divisions work in concert to regulate visceral activity (respiration, cardiovascular function, digestion, and associated glandular activity).

**66**

**Autonomic Nervous System: Cholinergic and Adrenergic Synapses NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

### FIGURE 2.16 CHOLINERGIC AND ADRENERGIC SYNAPSES: SCHEMA

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is a two-neuron chain, with the preganglionic neuron arising from the central nervous system and synapsing on a postganglionic neuron located in a peripheral autonomic ganglion. Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter in both the sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia. The parasympathetic division of the ANS releases acetylcholine at its postganglionic synapses and is characterized as having cholinergic (C) effects, whereas the sympathetic division releases predominantly noradrenaline (norepinephrine) at its postganglionic synapses, causing adrenergic (A) effects (except on sweat glands, where acetylcholine is released). Although acetylcholine and noradrenaline are the chief transmitter substances, other neuroactive peptides often are colocalized with them and include such substances as gammaaminobutyric acid (GABA), substance P, enkephalins, histamine, glutamic acid, neuropeptide Y, and others.

**67**

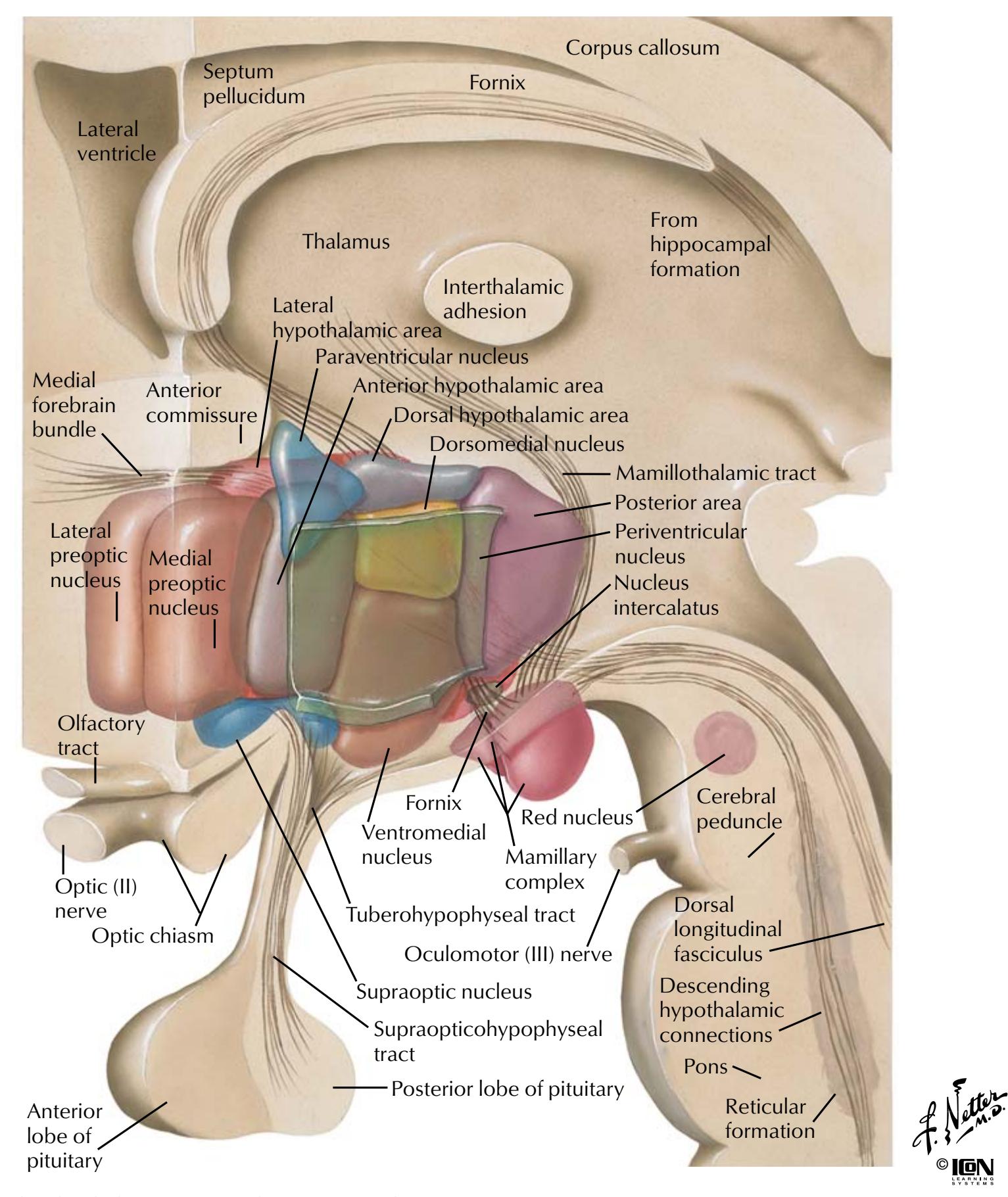

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Hypothalamus**

**CHART 2.3 MAJOR FUNCTIONS OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS**

| Hypothalamic Area | Major Functions* |

|-------------------------------------------------------|--------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Preoptic and anterior | Heat loss center: cutaneous vasodilation and sweating |

| Posterior | Heat conservation center: cutaneous vasoconstriction and shivering |

| Lateral | Feeding center: eating behavior |

| Ventromedial | Satiety center: inhibits eating behavior |

| Supraoptic (subfornical organ and organum vasculosum) | ADH and oxytocin secretion (sensation of thirst) |

| Paraventricular | ADH and oxytocin secretion |

| Periventricular | Releasing hormones for the anterior pituitary |

\*Stimulation of the center causes the responses listed.

### FIGURE 2.17 SCHEMATIC RECONSTRUCTION OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS

The hypothalamus, part of the diencephalon, controls a number of important homeostatic systems within the body, including temperature regulation, food intake, water intake, many of the endocrine systems (see Chapter 8), motivation, and emotional behavior. It receives inputs from the reticular formation (sleep/wake cycle

information), the thalamus (pain), the limbic system (emotion, fear, anger, smell), the medulla oblongata (blood pressure and heart rate), and the optic system, and it integrates these inputs for regulation of the functions listed.

**68**

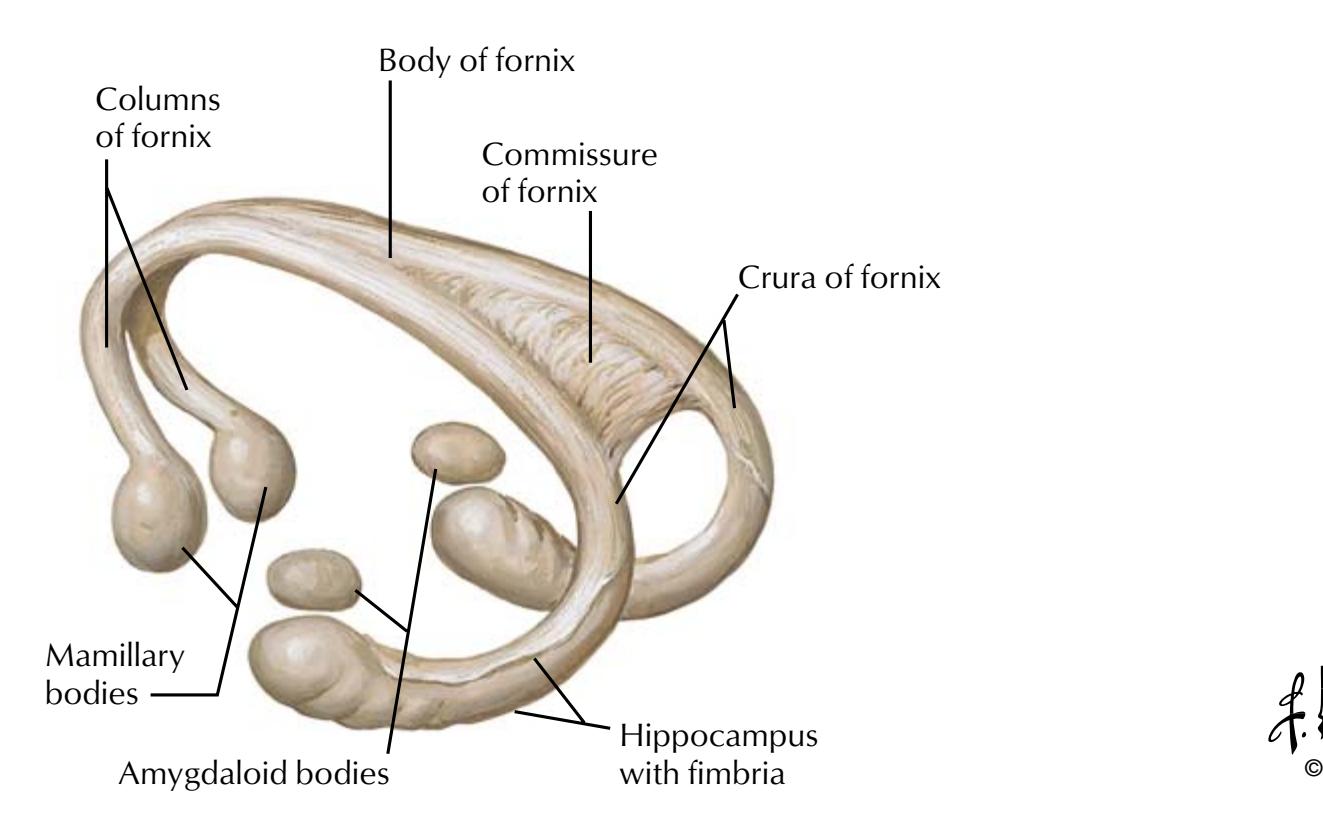

**Limbic System NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

### FIGURE 2.18 HIPPOCAMPUS AND FORNIX

The limbic system includes the hypothalamus and a collection of interconnected structures in the telencephalon (cingulate, parahippocampal, and subcallosal gyri), as well as the amygdala and hippocampal formation. The limbic system functions in linking emotion and motivation (amygdala), learning and memory (hippocampal formation), and sexual behavior (hypothalamus).

**69**

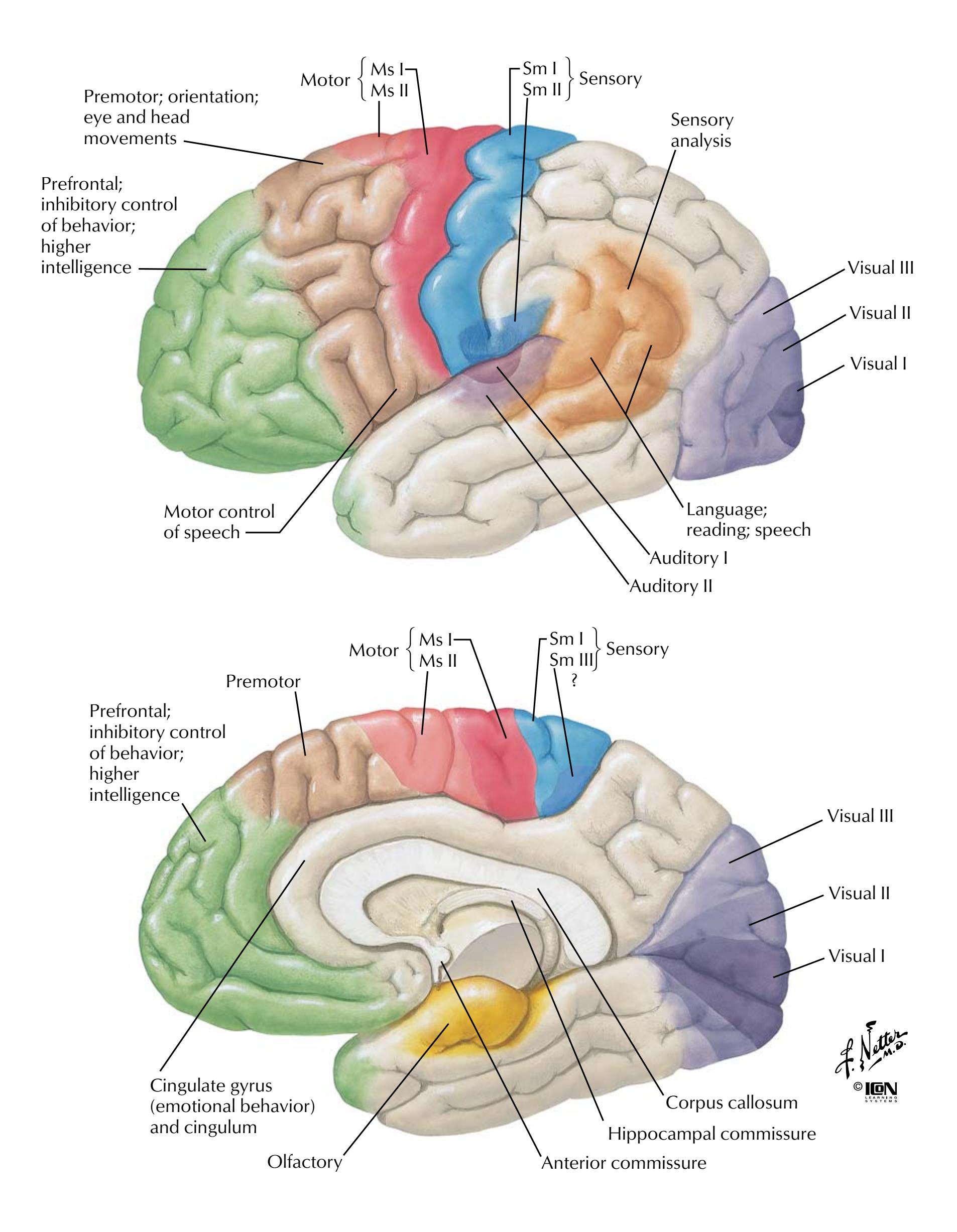

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY The Cerebral Cortex**

**FIGURE 2.19 CEREBRAL CORTEX: LOCALIZATION OF FUNCTION AND ASSOCIATION PATHWAYS•**

The cerebral cortex is organized into functional regions. In addition to specific areas devoted to sensory and motor functions, there are areas that integrate information from multiple sources. The cerebral cortex participates in advanced intellectual functions,

including aspects of memory storage and recall, language, higher cognitive functions, conscious perception, sensory integration, and planning/execution of complex motor activity. General cortical areas associated with these functions are illustrated.

**70**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Descending Motor Pathways**

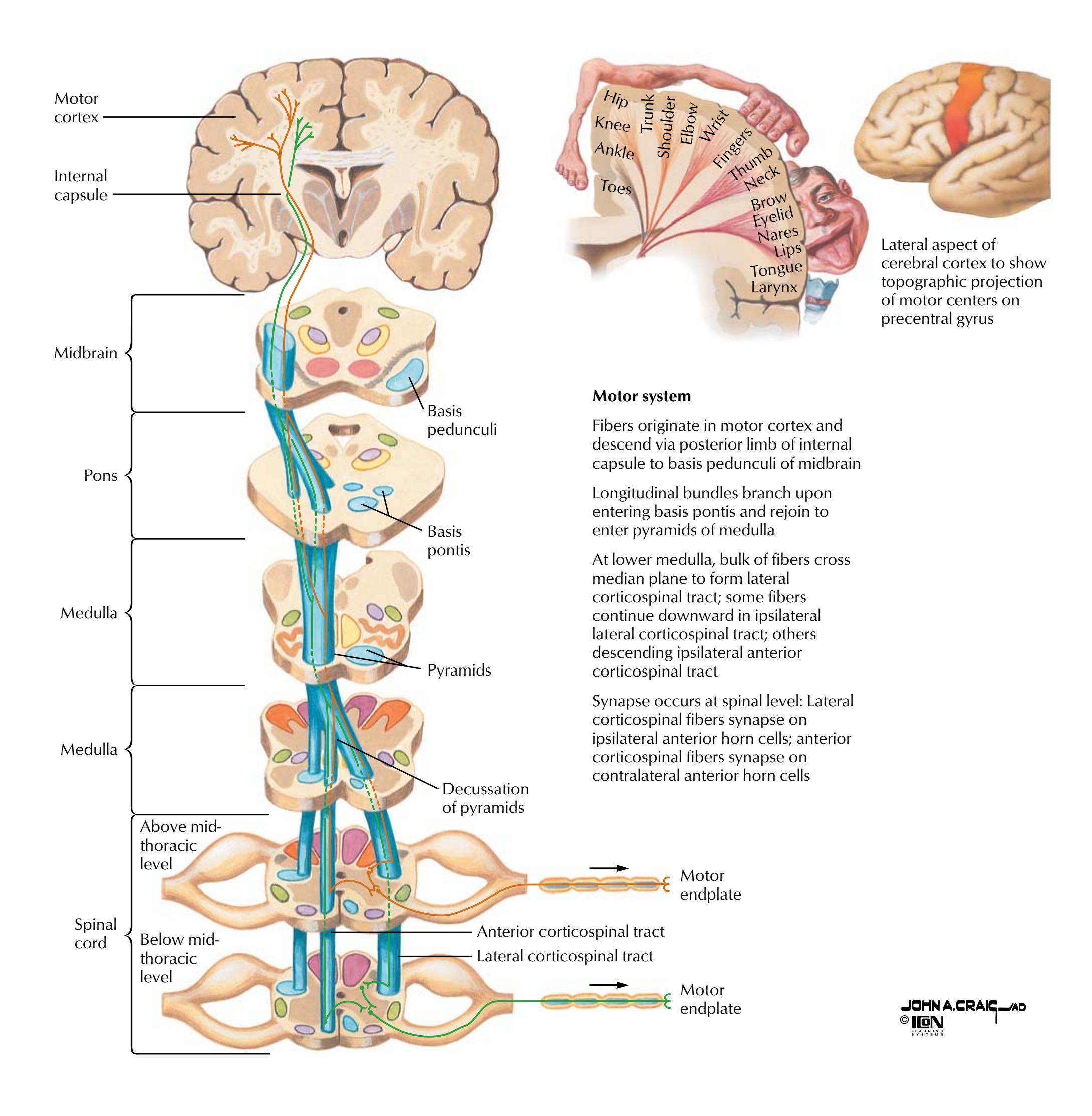

### FIGURE 2.20 CORTICOSPINAL TRACTS

The corticospinal, or pyramidal, tract is the major motor tract that controls voluntary movement of the skeletal muscles, especially skilled movements of distal muscles of the limbs. All structures from the cerebral cortex to the anterior horn cells in the spinal

cord constitute the upper portion of the system (upper motor neuron). The anterior horn cells and their associated axons constitute the lower portion of the system (lower motor neuron).

**71**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Cerebellum: Afferent Pathways**

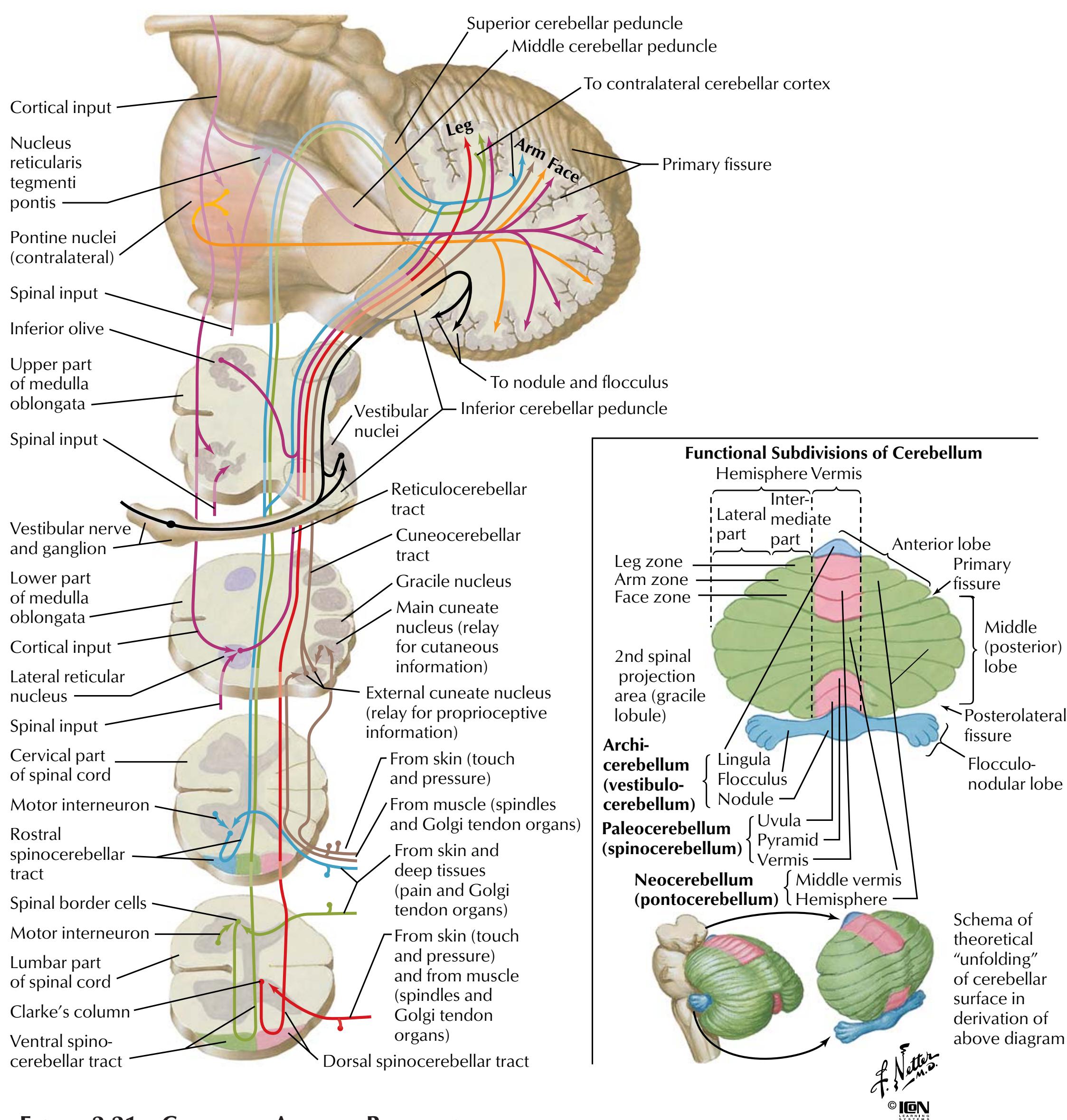

### FIGURE 2.21 CEREBELLAR AFFERENT PATHWAYS

The cerebellum plays an important role in coordinating movement. It receives sensory information and then influences descending motor pathways to produce fine, smooth, and coordinated motion. The cerebellum is divided into three general areas: archicerebellum (also called vestibulocerebellum) paleocerebellum (also called spinocerebellum) and the neocerebellum (also called the cerebrocerebellum). The archicerebellum is primarily involved in controlling posture and balance, as well as the movement of the head and eyes. It receives afferent signals from the vestibular apparatus and then sends efferent fibers to the appropriate descending motor pathways. The paleocerebellum primarily controls movement of the proximal portions of the limbs. It receives sensory information on limb position and muscle tone and then modifies and coordinates these movements through efferent pathways to the appropriate descending motor pathways. The neocerebellum is the largest portion of the cerebellum, and it coordinates the movement of the distal portions of the limbs. It receives input from the cerebral cortex and thus helps in the planning of motor activity (e.g., seeing a pencil and then planning and executing the movement of the arm and hand to pick it up).

**72**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Cerebellum: Efferent Pathways**

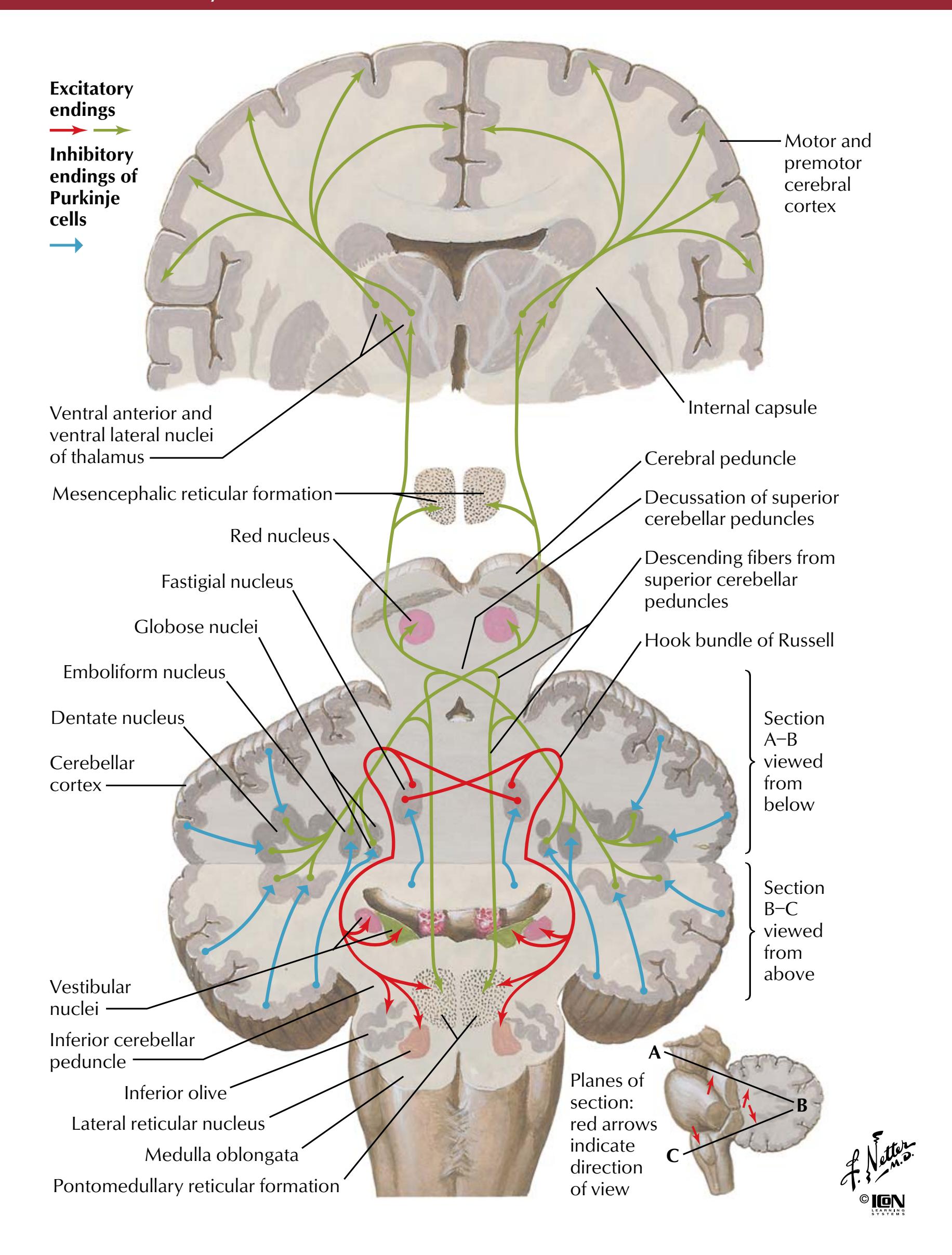

### FIGURE 2.22 CEREBELLAR EFFERENT PATHWAYS

The cerebellum plays an important role in coordinating movement. It influences descending motor pathways to produce fine, smooth, and coordinated motion. The archicerebellum is primarily involved in controlling posture and balance and movement of the head and eyes. It sends efferent fibers to the appropriate descending motor pathways. The paleocerebellum primarily controls movement of

the proximal portions of the limbs. It modifies and coordinates these movements through efferent pathways to the appropriate descending motor pathways. The neocerebellum coordinates the movement of the distal portions of the limbs. It helps in the planning of motor activity (e.g., seeing a pencil and then planning and executing the movement of the arm and hand to pick it up).

**73**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Cutaneous Sensory Receptors**

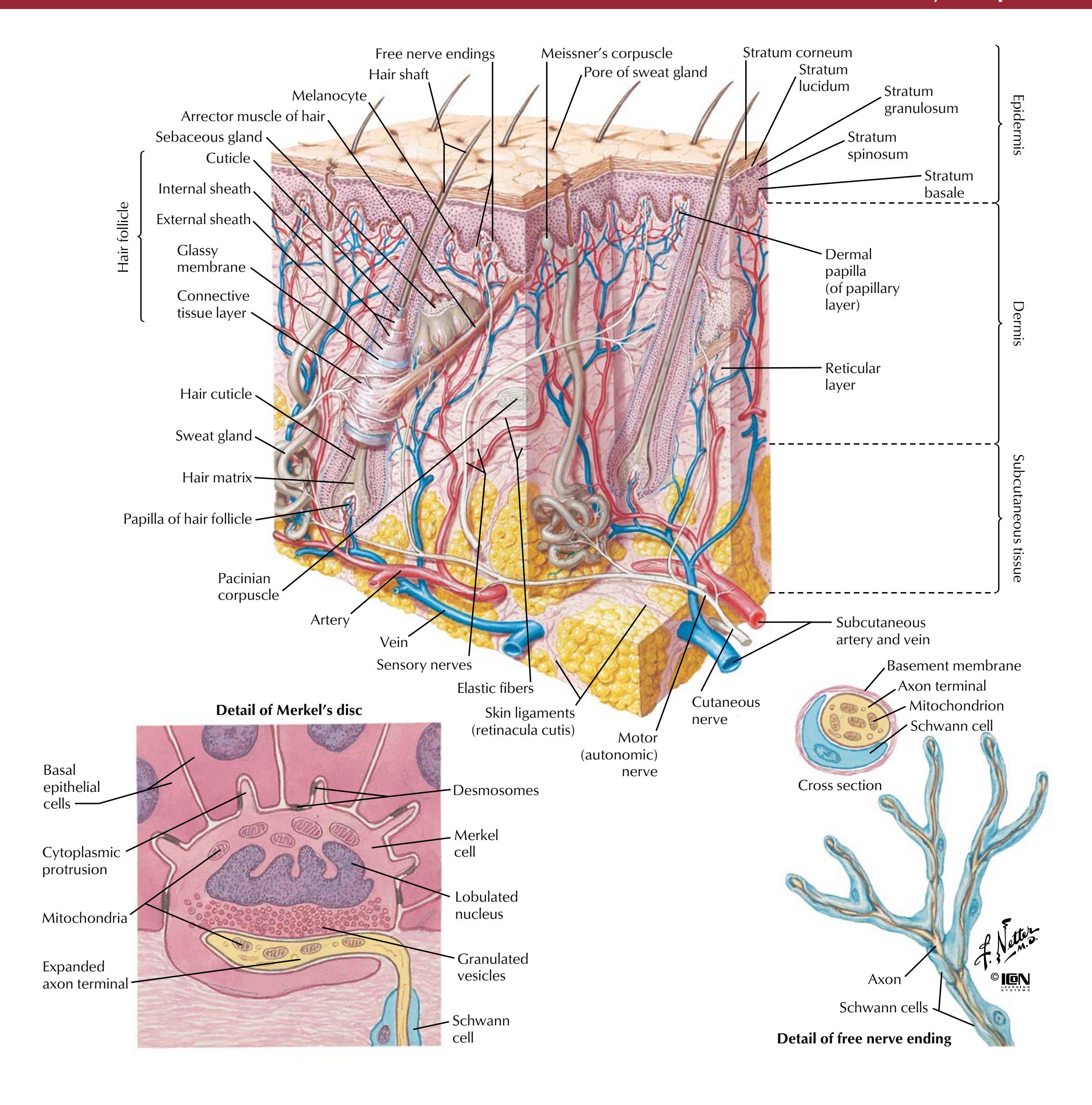

### FIGURE 2.23 SKIN AND CUTANEOUS RECEPTORS

Cutaneous receptors respond to touch (mechanoreceptors), pain (nociceptors), and temperature (thermoreceptors). Several different types of receptors are present in skin. Meissner's corpuscles have small receptive fields and respond best to stimuli that are applied at low frequency (i.e., flutter). The pacinian corpuscles are located in the subcutaneous tissue and have large receptive fields. They

respond best to high-frequency stimulation (i.e., vibration). Merkel's discs have small receptive fields and respond to touch and pressure (i.e., indenting the skin). Ruffini's corpuscles have large receptive fields, and they also respond to touch and pressure. Free nerve endings respond to pain and temperature.

**74**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

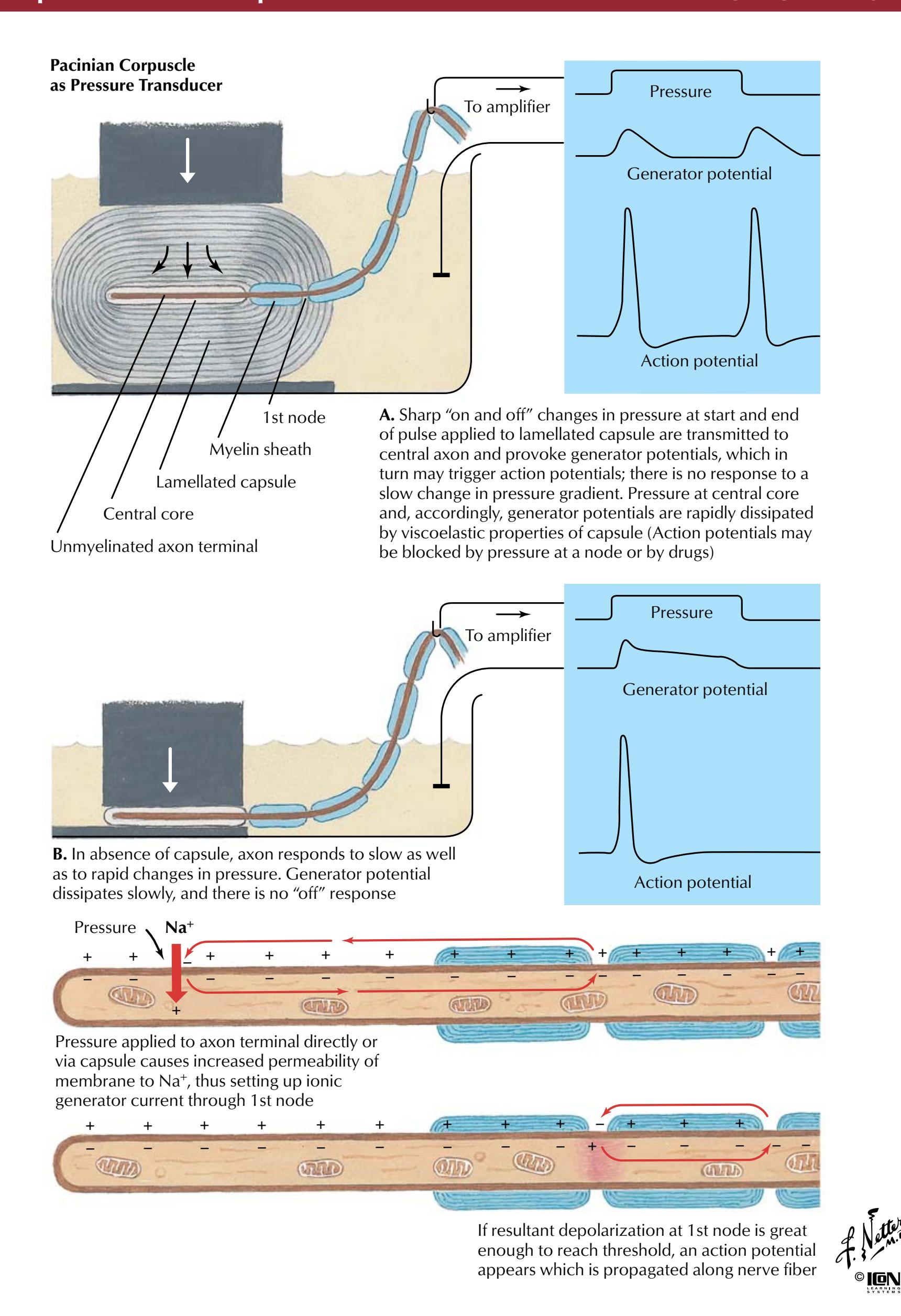

**Cutaneous Receptors: Pacinian Corpuscle**

### FIGURE 2.24 PACINIAN CORPUSCLE

Pacinian corpuscles are mechanoreceptors that transduce mechanical forces (displacement, pressure, vibration) into action potentials that are conveyed centrally by afferent nerve fibers. As the viscoelastic lamellae are displaced, the unmyelinated axon terminal membrane's ionic permeability is increased until it is capable of

producing a "generator potential." As demonstrated in the figure, pacinian corpuscles respond to the beginning and end of a mechanical force while the concentric lamellae dissipate slow changes in pressure. In the absence of the capsule, the generator potential decays slowly and yields only a single action potential.

**75**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: I**

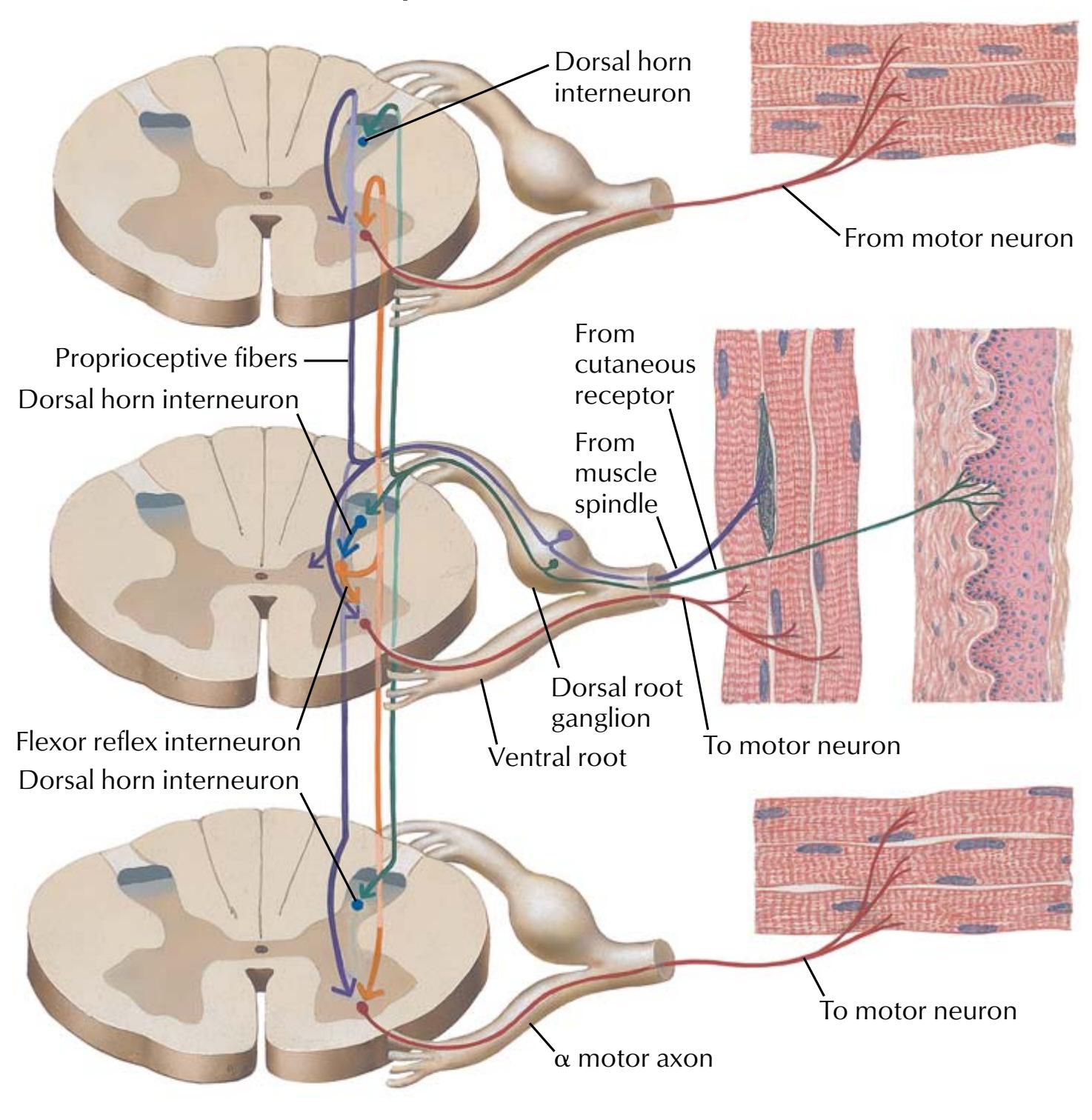

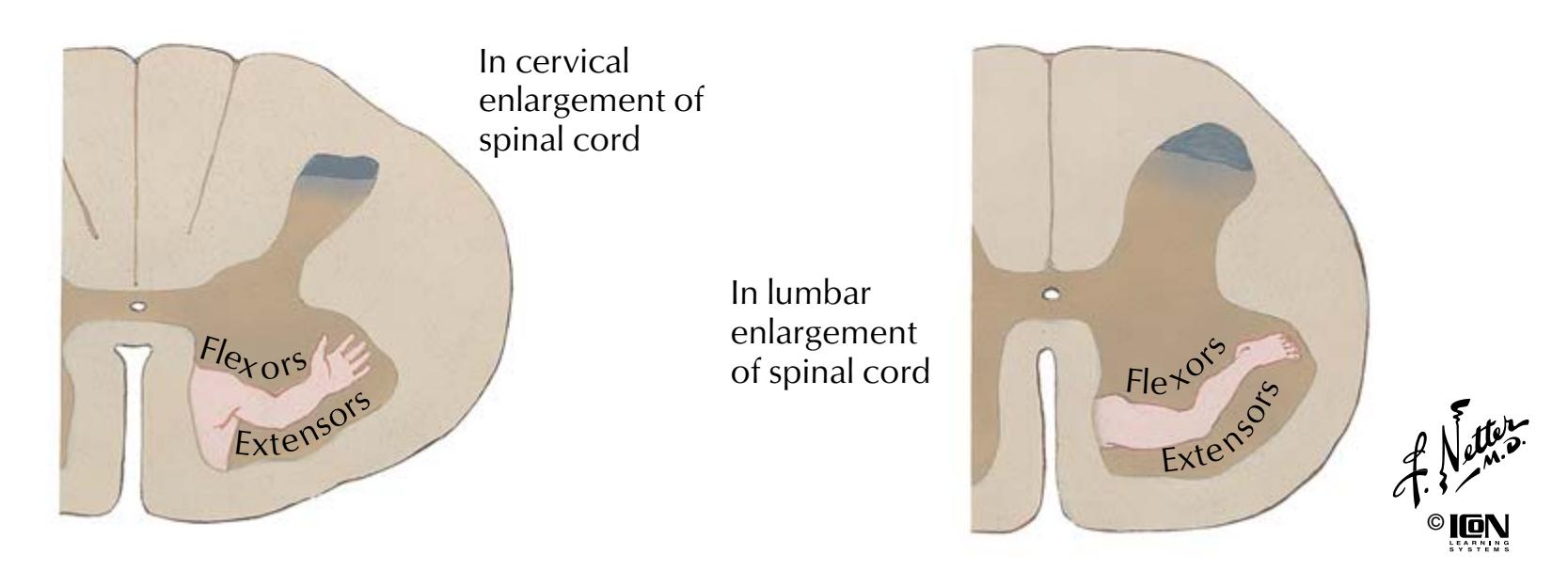

## Spinal Effector Mechanisms

### Schematic representation of motor neurons

### FIGURE 2.25 PROPRIOCEPTION: SPINAL EFFECTOR MECHANISM

Position sense or proprioception involves input from cutaneous mechanoreceptors, Golgi tendon organs, and muscle spindles (middle figure of upper panel). Both monosynaptic reflex pathways (middle figure of upper panel) and polysynaptic pathways involving several spinal cord segments (top and bottom figures of upper

panel) initiate muscle contraction reflexes. The lower panel shows the somatotopic distribution of the motor neuron cell bodies in the ventral horn of the spinal cord that innervate limb muscles (flexor and extensor muscles of upper and lower limbs).

**76**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

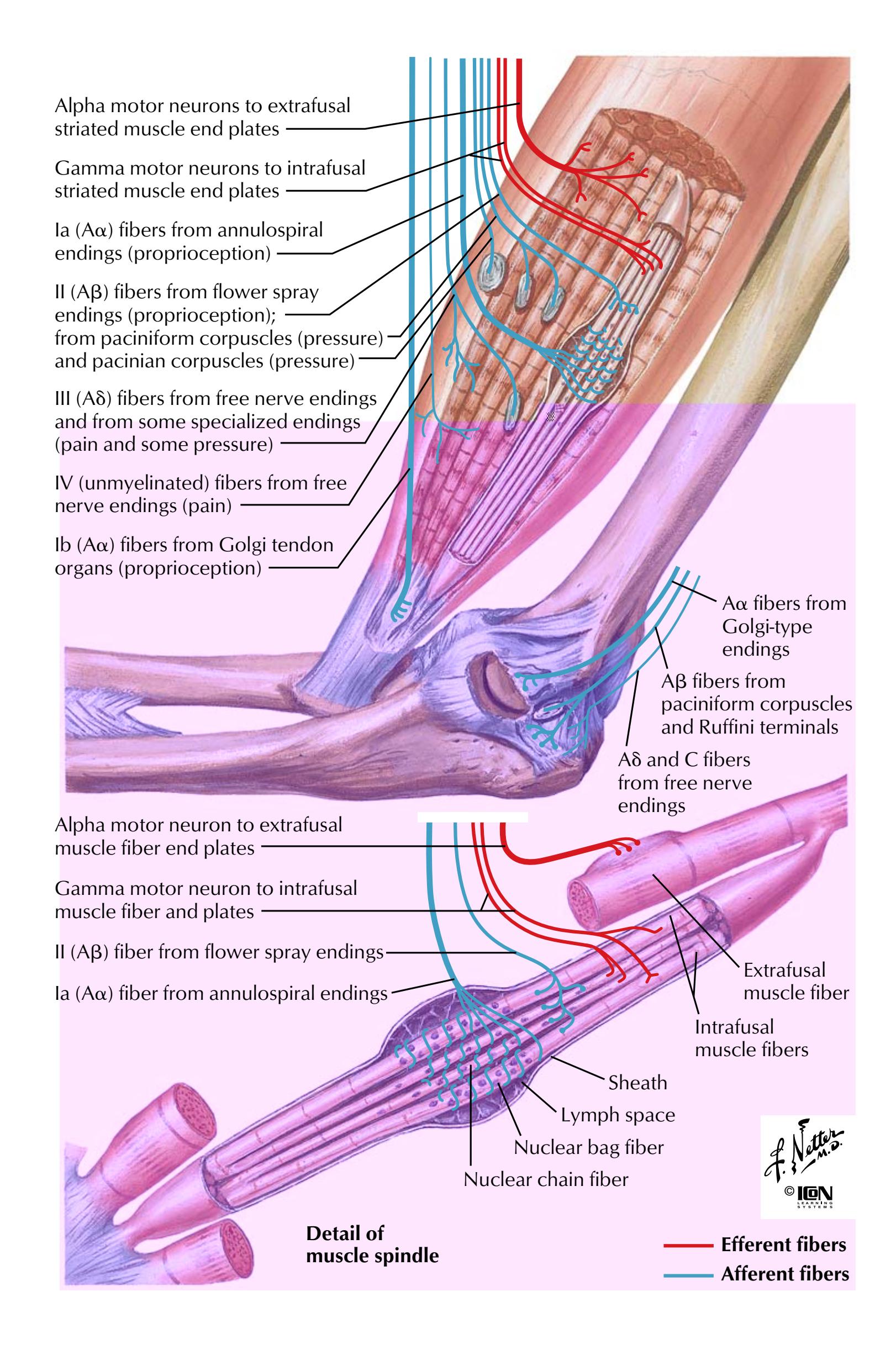

**Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: II**

### FIGURE 2.26 MUSCLE AND JOINT RECEPTORS

Muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs send afferent signals to the brain to convey the position of limbs and help coordinate muscle movement. Muscle spindles convey information on muscle tension and contraction (dynamic forces) and muscle length (static forces). The nuclear bag fibers respond to both dynamic and static

forces, whereas the nuclear chain fibers respond to static forces. Intrafusal fibers maintain appropriate tension on the nuclear bag and nuclear chain fibers. If the muscle tension is too great (e.g., overstretching of muscle or too heavy a load), activation of the Golgi tendon organ causes a reflex relaxation of the muscle.

**77**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: III**

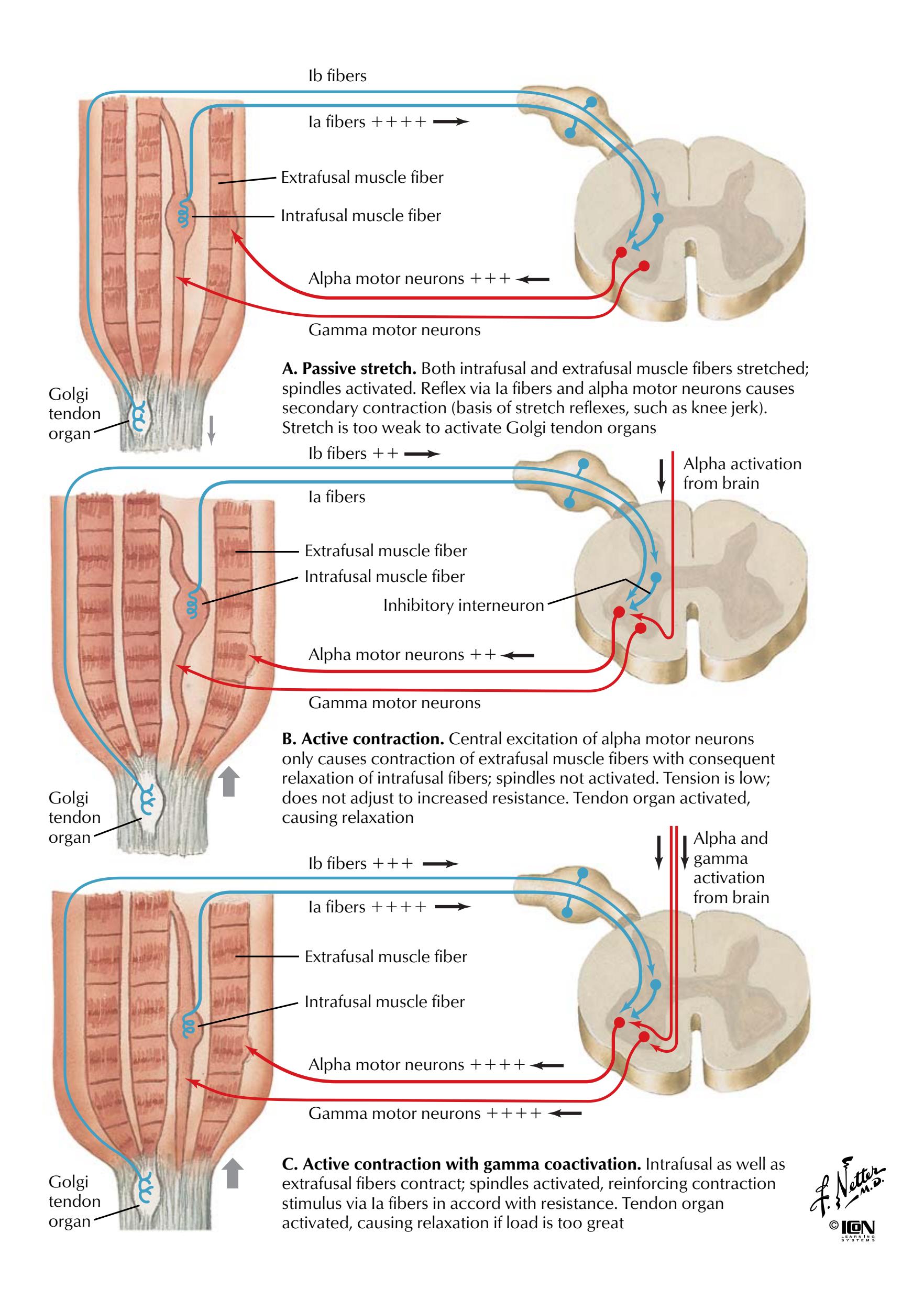

**FIGURE 2.27 PROPRIOCEPTIVE REFLEX CONTROL OF MUSCLE TENSION•**

Interaction of the muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ during passive stretch of a muscle (panel A) and during a contraction (panels B and C).

**78**

**Proprioception and Reflex Pathways: IV NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

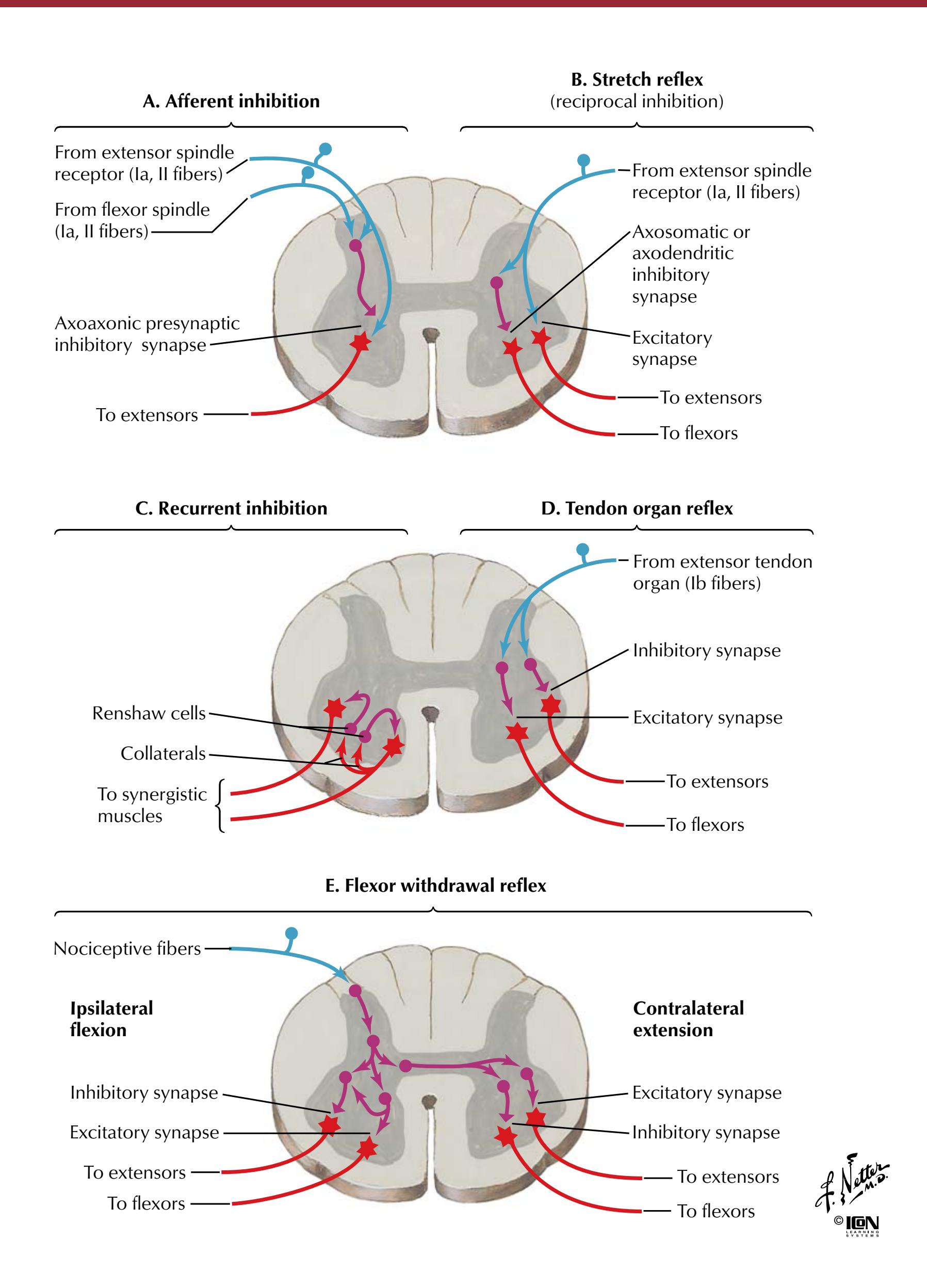

**FIGURE 2.28 SPINAL REFLEX PATHWAYS•**

Summary of the spinal reflex pathways.

**79**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Sensory Pathways: I**

### FIGURE 2.29 SOMESTHETIC SYSTEM OF THE BODY

Pain, temperature, and pressure sensations below the head ultimately are conveyed to the primary somatosensory cortex (postcentral gyrus) by the anterolateral system (spinothalamic and spinoreticular tracts). The fasciculus gracilis and cuneatus of the spinal lemniscal system convey proprioceptive, vibratory, and tactile sensations to the thalamus (ventral posterolateral nucleus), whereas the lateral cervical system mediates some touch, vibratory, and proprioceptive sensations (blue and purple lines show these dual pathways). Ultimately, these fibers ascend as parallel pathways to the thalamus, synapse, and ascend to the cortex.

**80**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Sensory Pathways: II**

### FIGURE 2.30 SOMESTHETIC SYSTEM OF THE HEAD

Nerve cells bodies for touch, pressure, pain, and temperature in the head are in the trigeminal (semilunar) ganglion of the trigeminal (CN V) nerve (blue and red lines in figure). Neuronal cell bodies mediating proprioception reside in the mesencephalic nucleus

of CN V (purple fibers). Most relay neurons project to the contralateral VPM nucleus of the thalamus and thence to the postcentral gyrus of the cerebral cortex, where they are somatotopically represented.

**81**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Sensory Pathways: III**

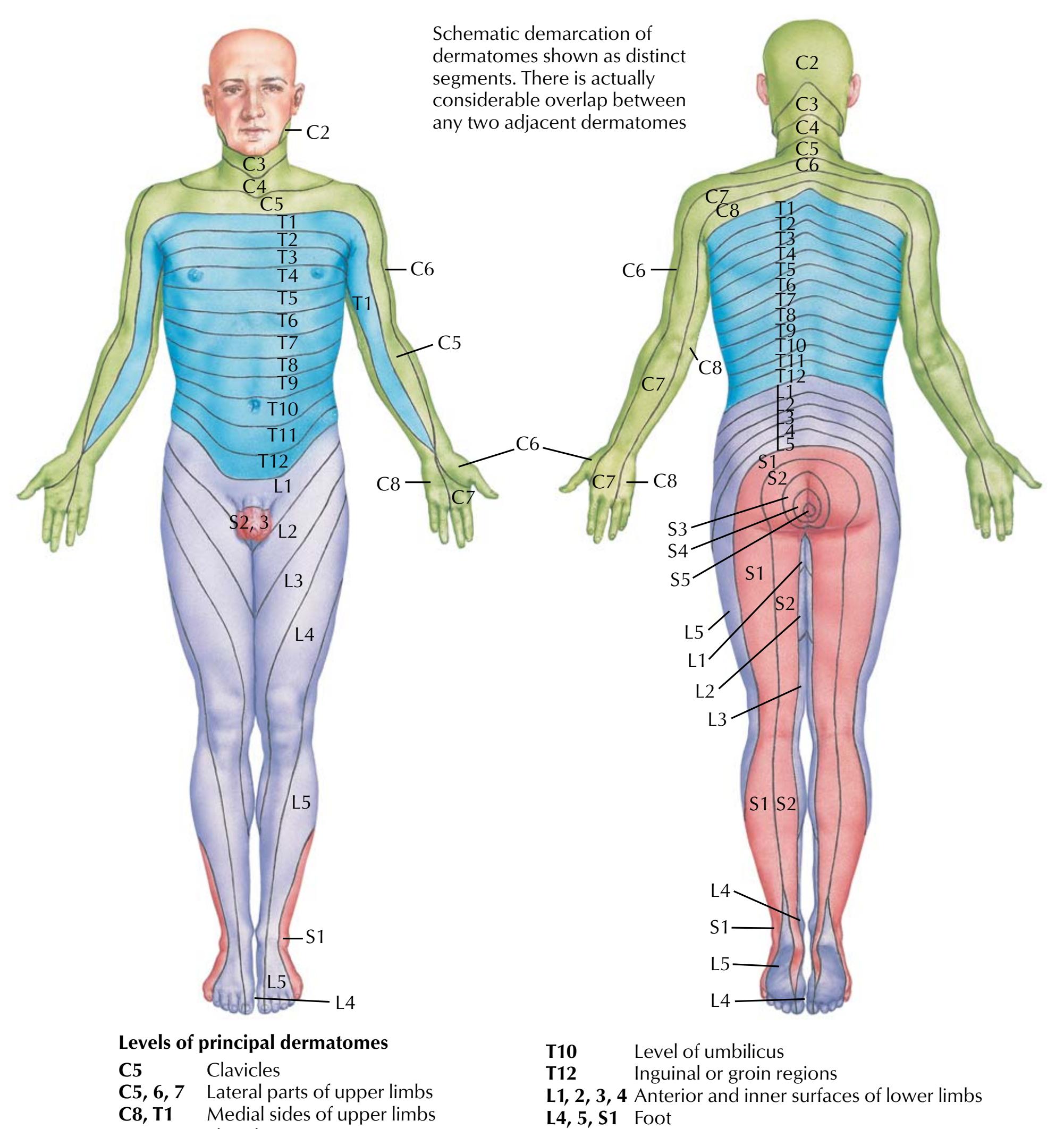

C8, T1 Medial sides of upper limbs

C6 C6, 7, 8 Thumb Hand

C8 T4 Ring and little fingers Level of nipples

L4 Medial side of great toe

S1, 2, L5 Posterior and outer surfaces of lower limbs

S1 Lateral margin of foot and little toe

S2, 3, 4 Perineum

### FIGURE 2.31 DERMATOMES

Sensory information below the head is localized to specific areas of the body, which reflect the distribution of peripheral sensory fibers that convey sensations to the spinal cord through the dorsal roots (sensory nerve cell bodies reside in the corresponding dorsal root ganglion). The area of skin subserved by afferent fibers of one

dorsal root is called a dermatome. This figure shows the dermatome segments and lists key dermatome levels used by clinicians. Variability and overlap occur, so all dermatome segments are only approximations.

**82**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Visual System: Receptors**

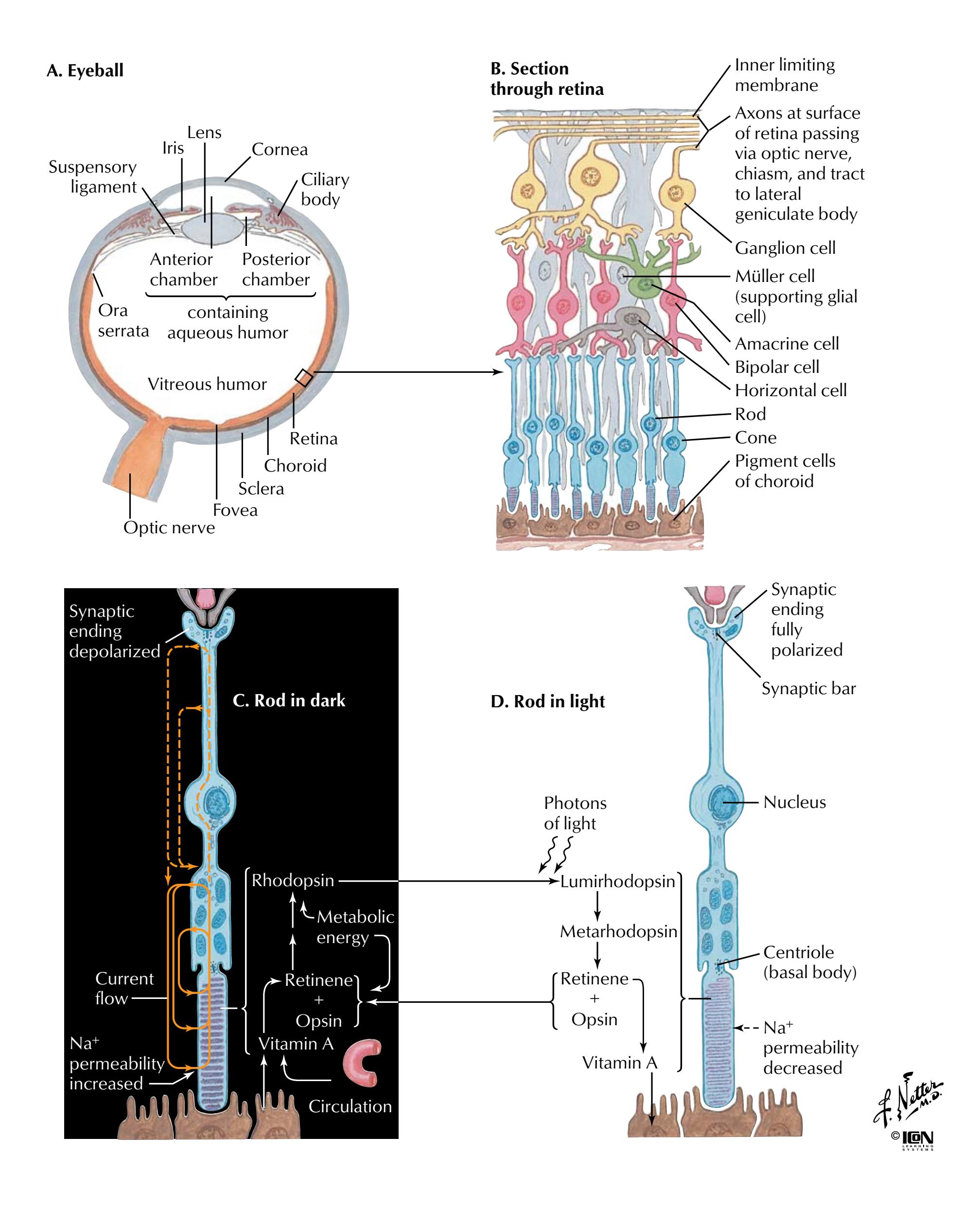

### FIGURE 2.32 VISUAL RECEPTORS

The rods and cones of the retina transduce light into electrical signals. As illustrated for the rod, light is absorbed by rhodopsin, and through the second messenger cGMP (not shown), Na channels in the membrane close and the cell hyperpolarizes. Thus, in the

dark the cell is depolarized, but it is hyperpolarized in the light. This electrical response to light is distinct from other receptor responses, in which the response to a stimulus results in a depolarization of the receptor cell membrane.

**83**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

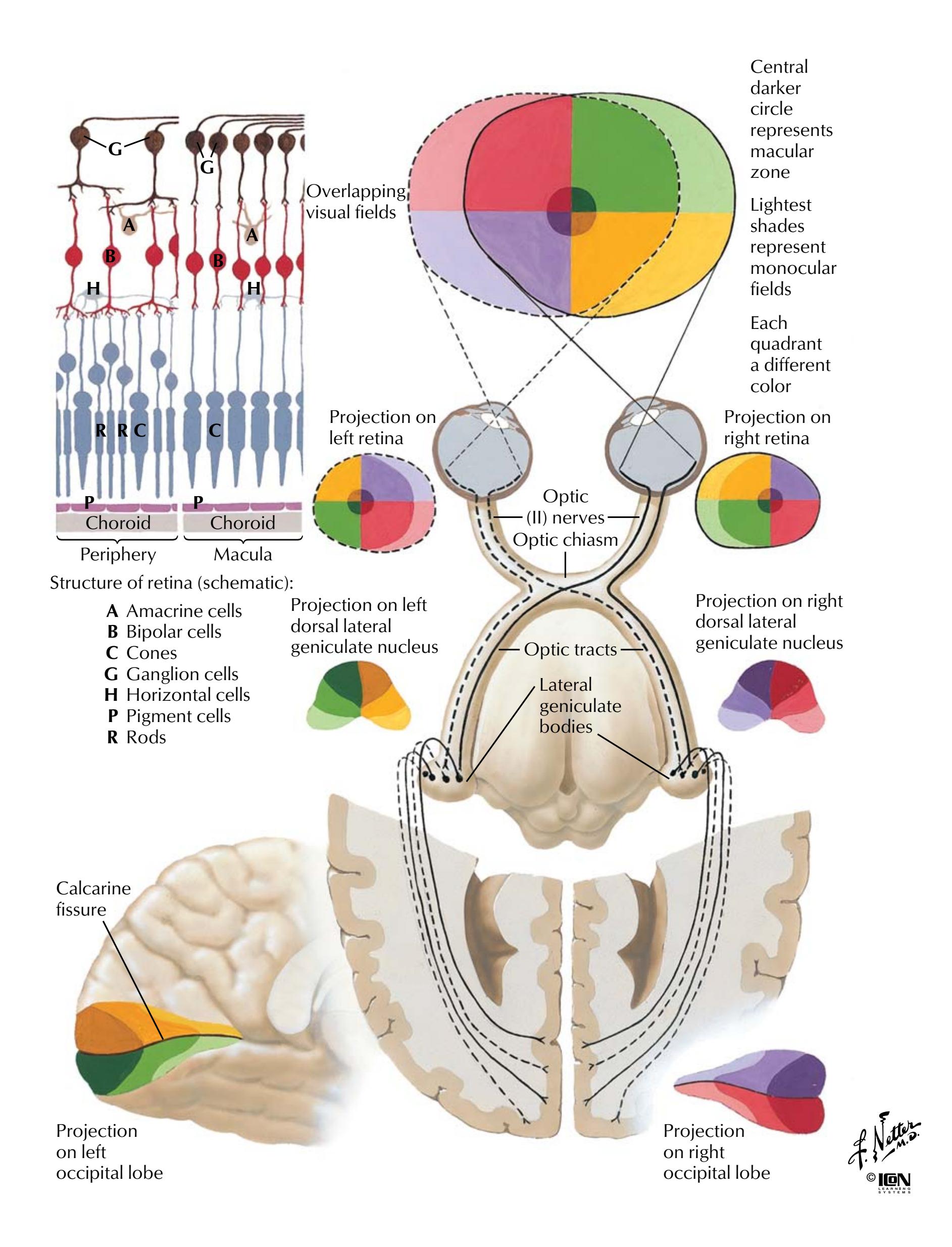

**Visual System: Visual Pathway**

### FIGURE 2.33 RETINOGENICULOSTRIATE VISUAL PATHWAY

The retina has two types of photoreceptors: cones that mediate color vision and rods that mediate light perception but with low acuity. The greatest acuity is found in the region of the macula of the retina, where only cones are found (upper left panel). Visual signals are conveyed by the ganglion cells whose axons course in the optic nerves. Visual signals from the nasal retina cross in the

optic chiasm while information from the temporal retina remains in the ipsilateral optic tract. Fibers synapse in the lateral geniculate nucleus (visual field is topographically represented here and inverted), and signals are conveyed to the visual cortex on the medial surface of the occipital lobe.

**84**

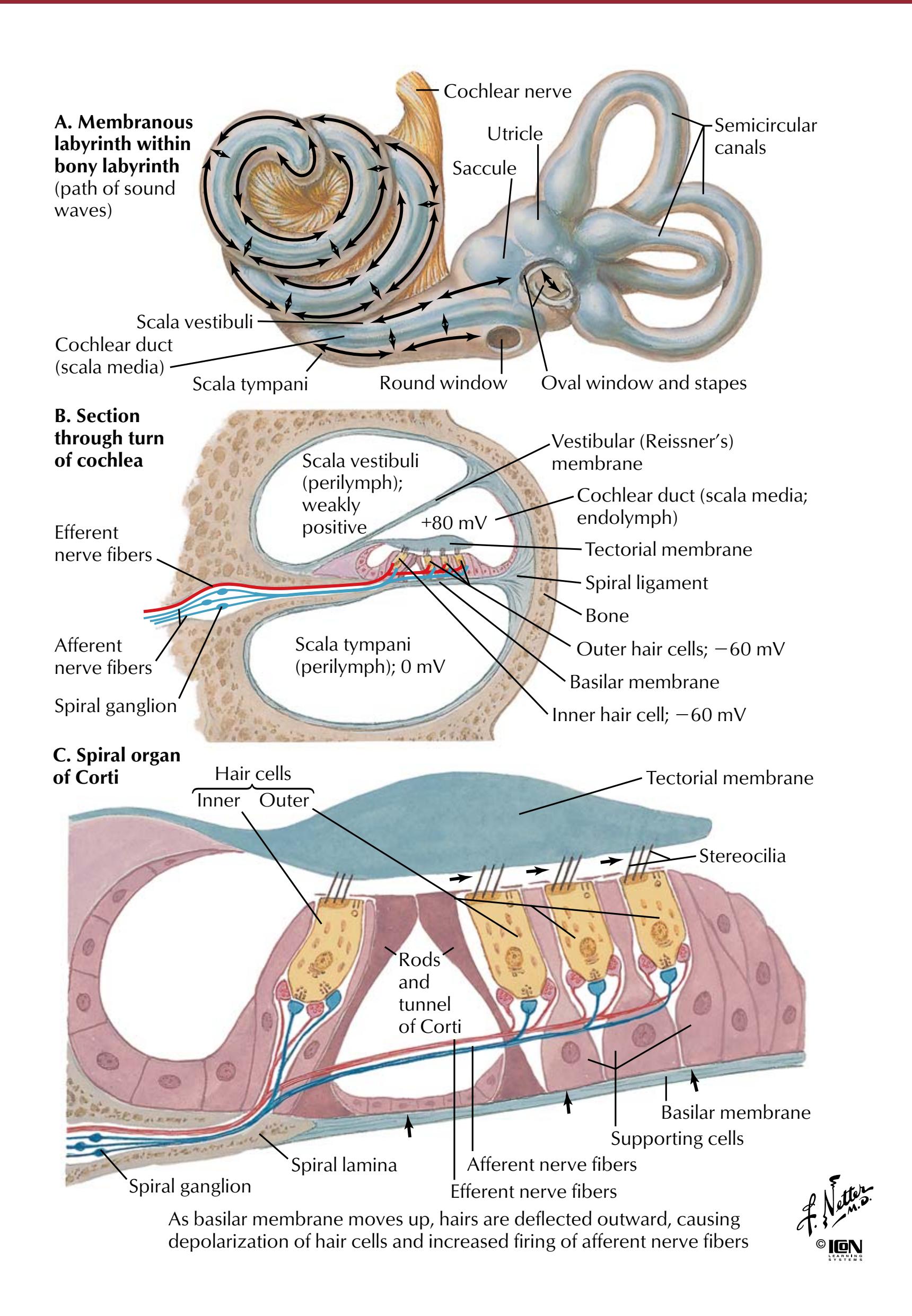

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Auditory System: Cochlea**

### FIGURE 2.34 COCHLEAR RECEPTORS

The cochlea transduces sound into electrical signals. This is accomplished by the hair cells, which depolarize in response to vibration of the basilar membrane. The basilar membrane moves in response to pressure changes imparted on the oval window of the cochlea in response to vibrations of the tympanic membrane.

**85**

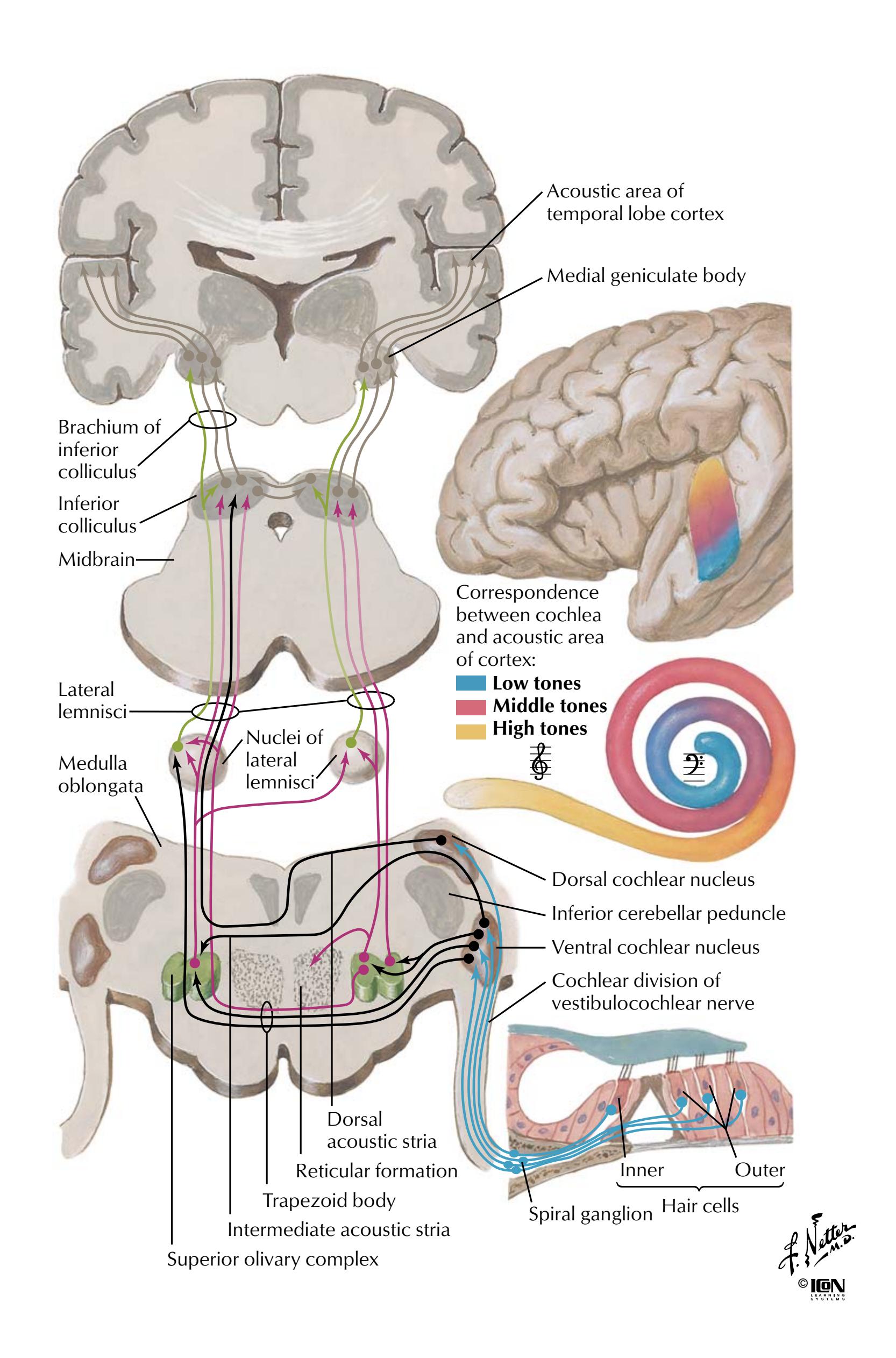

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Auditory System: Pathways**

### FIGURE 2.35 AUDITORY PATHWAYS

The cochlea transduces sound into electrical signals. Axons convey these signals to the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei, where it is tonotopically organized. Following a series of integrated relay pathways, the ascending pathway projects to the thalamus (medial

geniculate bodies) and then the acoustic cortex in the transverse gyrus of the temporal lobe, where information is tonotopically represented (low, middle, and high tones).

**86**

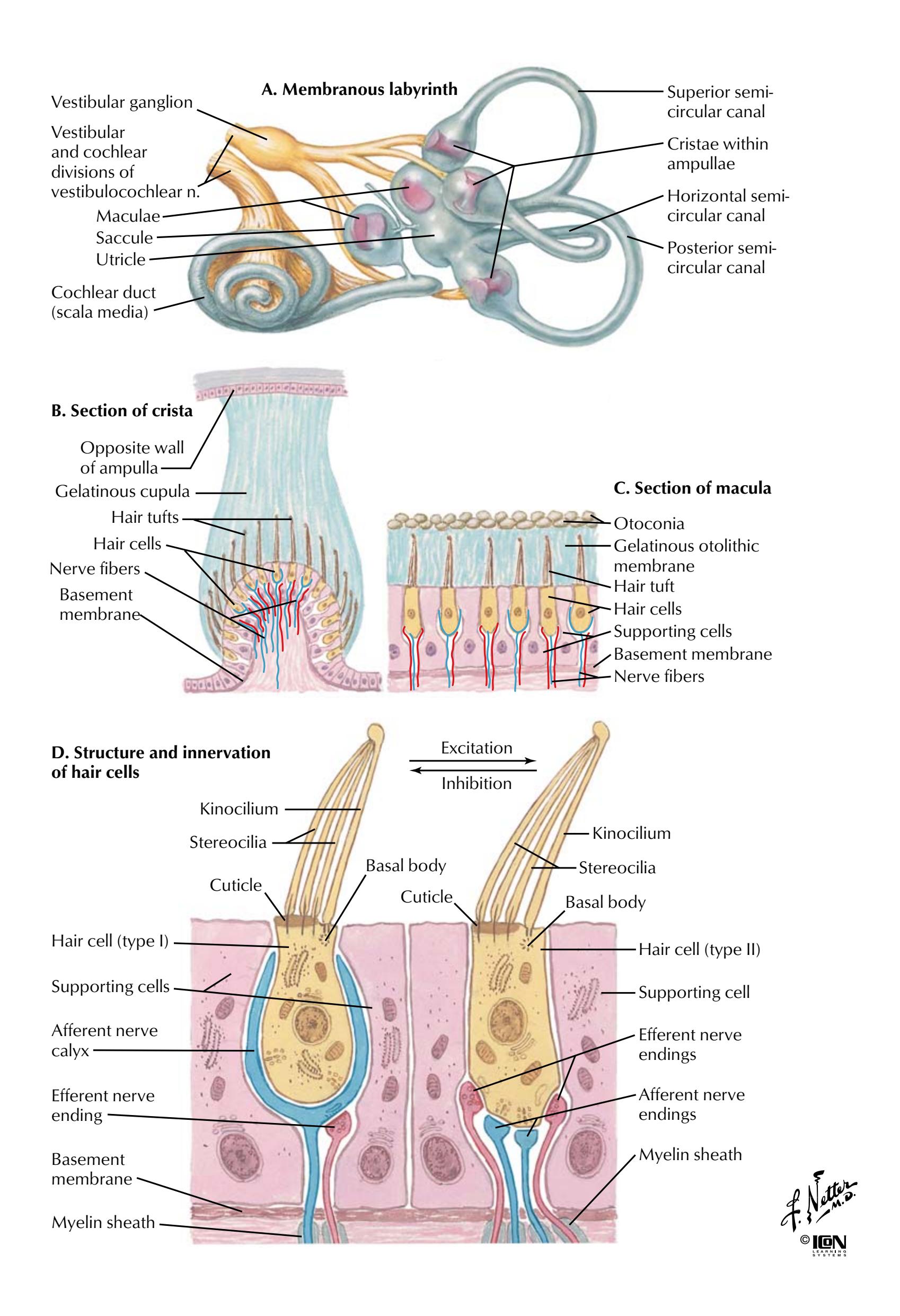

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**Vestibular System: Receptors**

### FIGURE 2.36 VESTIBULAR RECEPTORS

The vestibular apparatus detects movement of the head in the form of linear and angular acceleration. This information is important for the control of eye movements so that the retina can be provided with a stable visual image. It is also important for the control of posture. The utricle and saccule respond to linear acceleration,

such as the pull of gravity. The three semicircular canals are aligned so that the angular movement of the head can be sensed in all planes. The sensory hair cells are located in the maculae of the utricle and saccule and in the cristae within each ampullae.

**87**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Vestibular System: Vestibulospinal Tracts**

### FIGURE 2.37 VESTIBULOSPINAL TRACTS

Sensory input from the vestibular apparatus is used to maintain stability of the head and to maintain balance and posture. Axons convey vestibular information to the vestibular nuclei in the pons, and then secondary axons distribute this information to five sites: spinal cord (muscle control), cerebellum (vermis), reticular formation (vomiting center), extraocular muscles, and cortex (conscious perception). This figure shows only the spinal cord pathways.

**88**

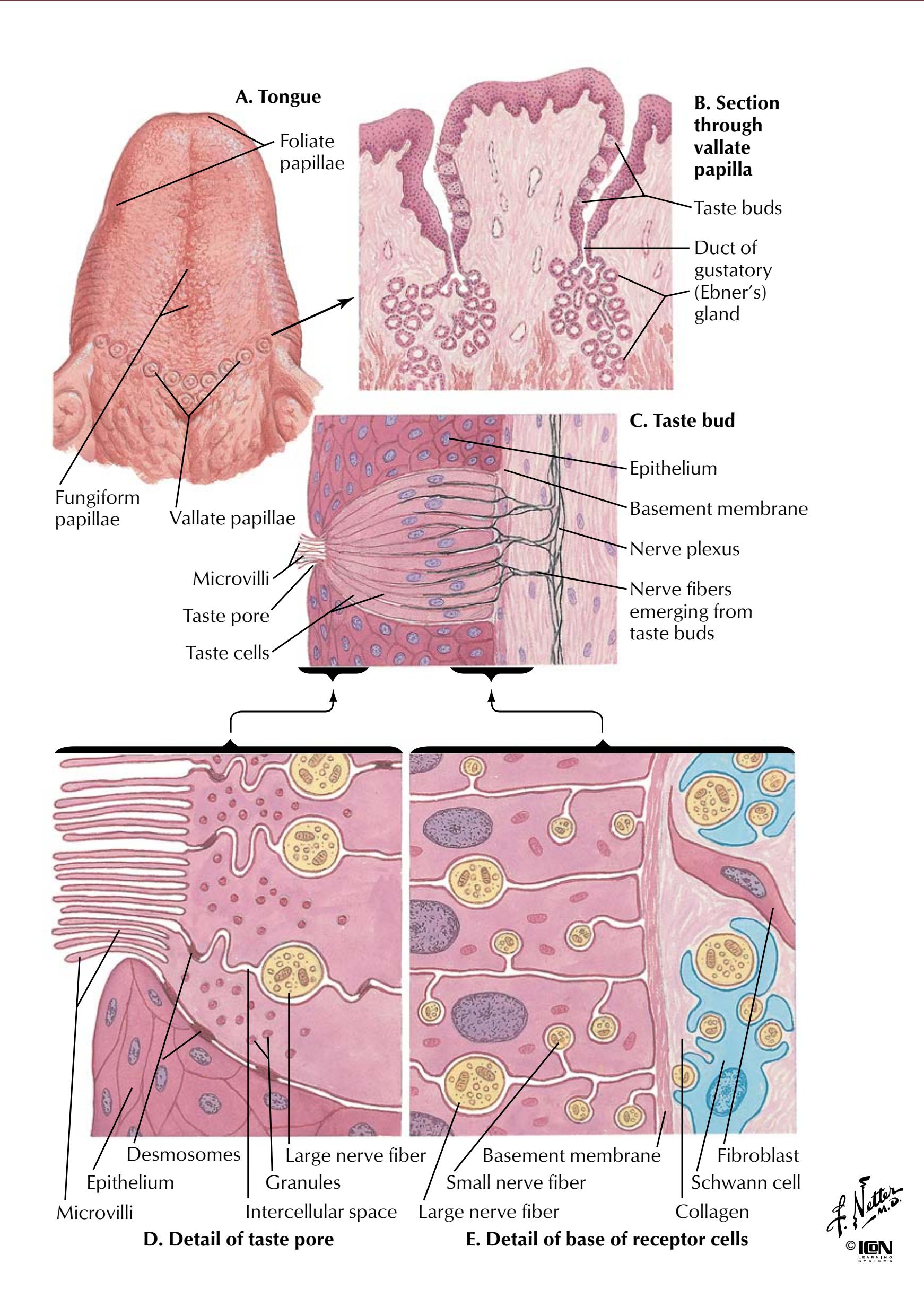

**Gustatory (Taste) System: Receptors NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

### FIGURE 2.38 TASTE RECEPTORS

Taste buds on the tongue respond to various chemical stimuli. Taste cells, like neurons, normally have a net negative charge internally and are depolarized by stimuli, thus releasing transmitters that depolarize neurons connected to the taste cells. A single taste bud can respond to more than one stimulus. The four traditional taste qualities that are sensed are sweet, salty, sour, and bitter.

**89**

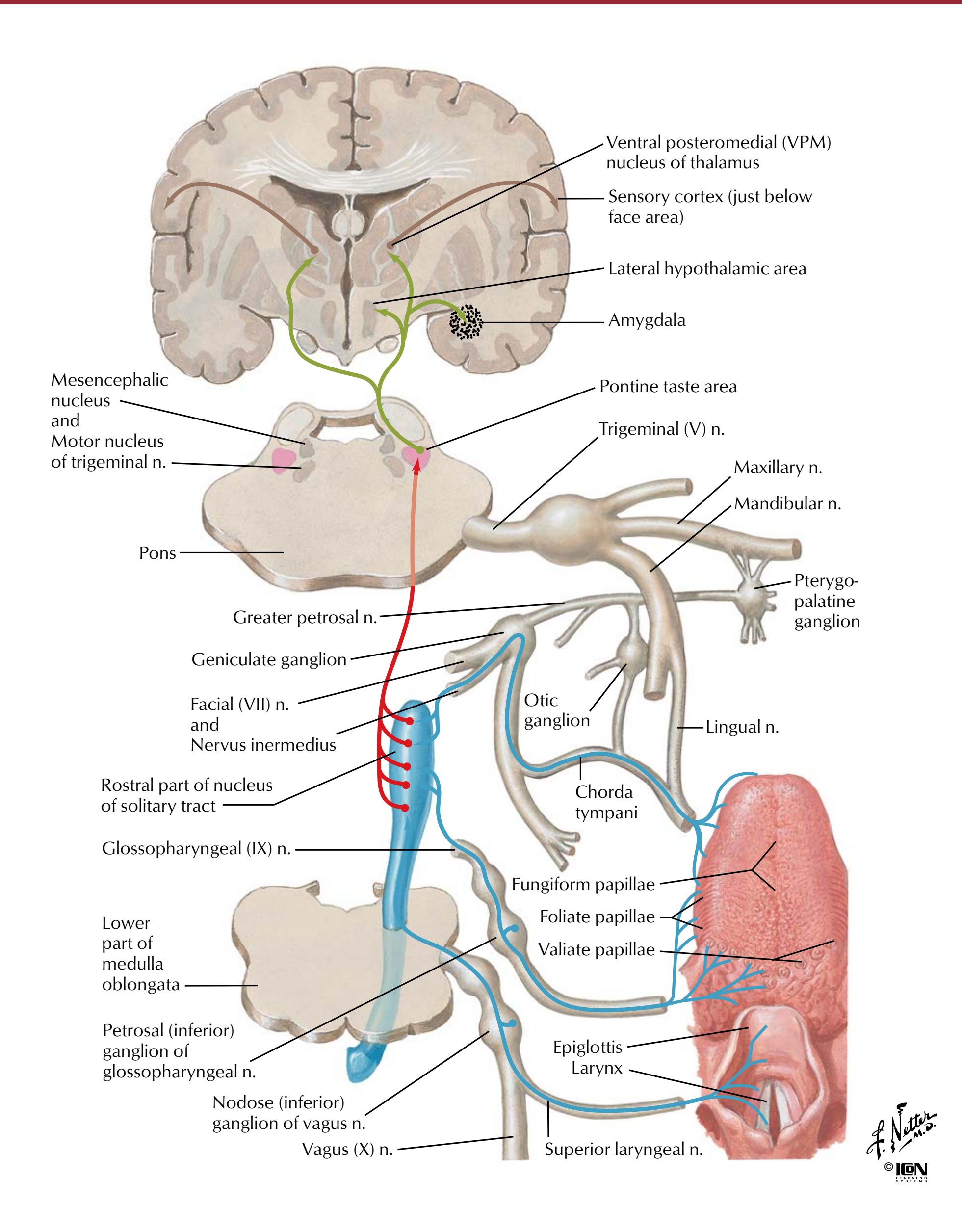

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Gustatory (Taste) System: Pathways**

**FIGURE 2.39 TASTE PATHWAYS•**

Depicted here are the afferent pathways leading from the taste receptors to the brainstem and, ultimately, to the sensory cortex in the postcentral gyrus.

**90**

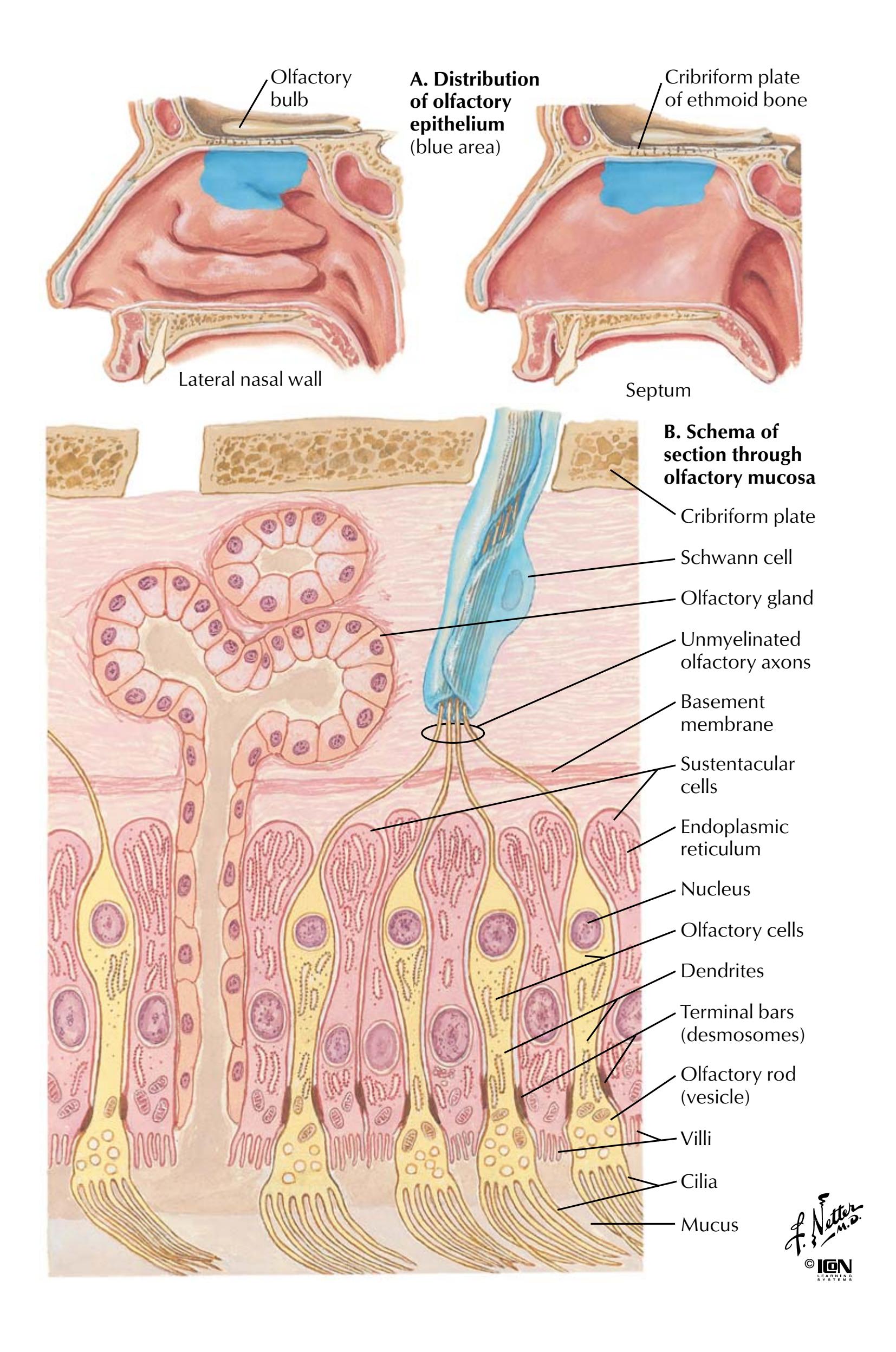

**Olfactory System: Receptors NEUROPHYSIOLOGY**

**FIGURE 2.40 OLFACTORY RECEPTORS•**

The sensory cells that make up the olfactory epithelium respond to odorants by depolarizing. Like taste buds, an olfactory cell can respond to more than one odorant. There are six general odor

qualities that can be sensed: floral, ethereal (e.g., pears), musky, camphor (e.g., eucalyptus), putrid, and pungent (e.g., vinegar, peppermint).

**91**

**NEUROPHYSIOLOGY Olfactory System: Pathway**

### FIGURE 2.41 OLFACTORY PATHWAY

Olfactory stimuli are detected by the nerve fibers of the olfactory epithelium and conveyed to the olfactory bulb (detailed local circuitry shown in upper left panel). Integrated signals pass along the olfactory tract and centrally diverge to pass to the anterior commissure (some efferent projections course to the contralateral olfactory bulb, blue lines) or terminate in the ipsilateral olfactory trigone (olfactory tubercle). Axons then project to the primary olfactory cortex (piriform cortex), entorhinal cortex, and amygdala.

**92**

# Installing Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0

The images and text included in this atlas are contained in a Portable Document Format (pdf) file and can be viewed with Adobe Acrobat Reader. A copy of Acrobat Reader 5.0 is included on this CD. You will need to install or upgrade to Acrobat Reader 5.0 in order to have full functionality.

Please follow these instructions:

- 1. Choose Run from the Start menu and then click Browse.

- 2. Double-click the InstallAcrobat.exe file to open the Reader Installer.

- 3. Follow the onscreen instructions.

## Running the Atlas of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology

### Windows

- 1. Insert the CD into the CD-ROM drive.

- 2. If Acrobat Reader 5.0 is not already installed on your computer, follow the installation instructions above.

- 3. Choose Run from the Start menu and type x:\ (where x is the letter of your CD-ROM drive).

- 4. Under Files of Type, click All Files.

- 5. Double-click the Neuro Atlas.pdf file to open the program.

- 6. For best viewing results, use the Edit menu to access the Preferences. Select General and open the Display preferences to activate the Smooth Line Art option.

### Macintosh

- 1. Insert the CD into the CD-ROM drive.

- 2. If Acrobat Reader 5.0 is not already installed on your computer, follow the installation instructions above.

- 3. Double-click the Neuro Atlas.pdf file to open the program.

- 4. For best viewing results, use the Edit menu to access the Preferences. Select General and open the Display preferences to activate the Smooth Line Art option.

All rights reserved. No material on this CD-ROM may be reproduced in any electronic format, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Send requests for permissions to Permissions Editor, Icon Custom Communications, 295 North St., Teterboro NJ 07608, or visit www.netterart.com/request.cfm.