# **Brief Contents**

- **[Preface](#page--1-0)** ix

- **Chapter 1** [The Science of Psychology](#page-4-0) 2

- **Chapter 2** [Research Methodology](#page-83-0) 28

- **Chapter 3** [Biology and Behavior](#page-188-0) 66

- **Chapter 4** [Consciousness](#page-326-0) 118

- **Chapter 5** [Sensation and Perception](#page-431-0) 158

- **[Chapter 6](#page-550-0)** Learning 202

- **[Chapter 7](#page-664-0)** Memory 242

- **Chapter 8** [Thinking, Decisions, Intelligence, and Language](#page-772-0) 282

- **Chapter 9** [Human Development](#page-904-0) 328

- **Chapter 10** [Emotion and Motivation](#page-1028-0) 374

- **Chapter 11** [Health and Well-Being](#page-1130-0) 410

- **Chapter 12** [Social Psychology](#page-1222-0) 444

- **Chapter 13** [Personality](#page-1356-0) 494

- **Chapter 14** [Psychological Disorders](#page-1458-0) 538

- **Chapter 15** [Treatment of Psychological Disorders](#page-1603-0) 594

- **[Answer Key for Practice Exercises](#page--1-1)** A-1

- **[Glossary](#page--1-0)** G-1

- **[References](#page--1-0)** R-1

- **[Permissions Acknowledgments](#page--1-0)** P-1

- **[Name Index](#page--1-0)** N-1

- **[Subject Index](#page--1-0)** S-1

# **The Science of Psychology**

# Big Questions

- [What Is Psychological Science? 4](#page-6-0)

- [What Is the Scientific Scope of Psychology? 9](#page-21-0)

- [What Are the Latest Developments in Psychology? 15](#page-43-0)

**WHY IS PSYCHOLOGY ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR MAJORS** at many colleges? The simple answer is that people want to understand the minds and actions of themselves and others. Knowing how humans think, feel, and behave can be incredibly useful. The science of psychology can help you understand your motives, your personality, even why you remember some things and forget others. In addition, psychology will prepare you for many professions, and much of the research you will read about in this book can be used to make people's lives better. It will benefit you whether you're studying environmental science (how do you encourage people to recycle?), anthropology (how does culture shape behavior?), biology (how do animals learn?), or philosophy (do people have free will?). Whatever your major, this class will help you succeed in your academic work and your broader life beyond it, now and in the future.

# What Is Psychological Science?

# Learning Objectives

- Define psychological science.

- Define critical thinking, and describe what it means to be a critical thinker.

- Identify major biases in thinking, and explain why these biases result in faulty thinking.

*Psychology* involves the study of thoughts, feelings, and behavior. The term *psychologist* is used broadly to describe someone whose career involves understanding people's minds or predicting their behavior. We humans are intuitive psychologists. We could not function very well in our world without natural ways to understand and predict others' behavior. For example, we quite rapidly get a sense of whether we can trust a stranger before we interact with them. But we cannot simply use our own common sense or gut feelings as a guide to know whether many of the claims related to psychology are fact or fiction. Will playing music to newborns make them more intelligent? Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? Psychological science uses data to find answers.

# **1.1 Psychological Science Is the Study of Mind, Brain, and Behavior**

[Psychological science](#page-7-0) is the study, through research, of mind, brain, and behavior. But what exactly does each of these terms mean, and how are they all related?

*Mind* refers to mental activity. The mind includes the memories, thoughts, feelings, and perceptual experiences (sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and touches) we have while interacting with the world. Mental activity results from biochemical processes within the *brain*. *Behavior* describes the totality of observable human (or animal) actions. These actions range from the subtle to the complex. Some occur exclusively in humans, such as debating philosophy or performing surgery. Others occur in all animals, such as eating and drinking.

For many years, psychologists focused on behavior rather than on mental states. They did so largely because they had few objective techniques for assessing the mind. The advent of technology to observe the working brain in action has enabled psychologists to study mental states and has led to a fuller understanding of human behavior. Although psychological science is most often associated with its important contributions to understanding and treating mental disorders, much of the field seeks to understand mental activity (both typical and atypical), the biological basis of that activity, how people change as they develop through life, how people differ from one another, how people vary in their responses to social situations, and how people acquire healthy and unhealthy behaviors.

# How do the mind and the brain relate?

**Answer:** The mind (mental activity) is produced by biochemical processes in the brain.

# **Glossary**

# psychological science

The study, through research, of mind, brain, and behavior.

# 1.2 Psychological Science Teaches Critical Thinking

One of this textbook's most important goals is to provide a basic, state-of-the-art education about the methods of psychological science. Even if your only exposure to psychology is through the introductory course and this textbook, you will become psychologically literate. That means you will learn not only how to critically evaluate psychological claims you hear about in social and traditional media but also how to use data to answer your own questions about people's minds and behavior. With a good understanding of the field's major issues, theories, and controversies, you will also avoid common misunderstandings about psychology.

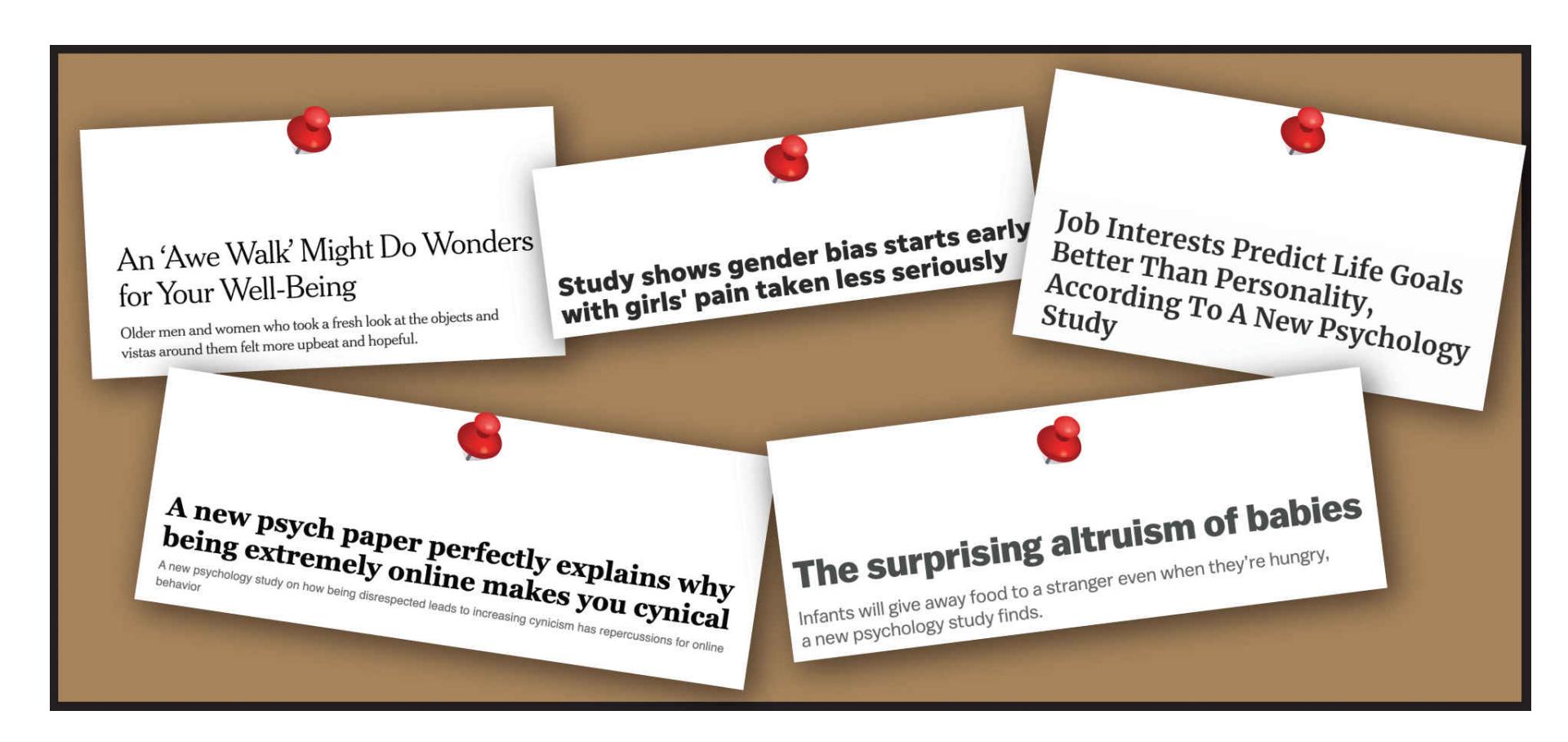

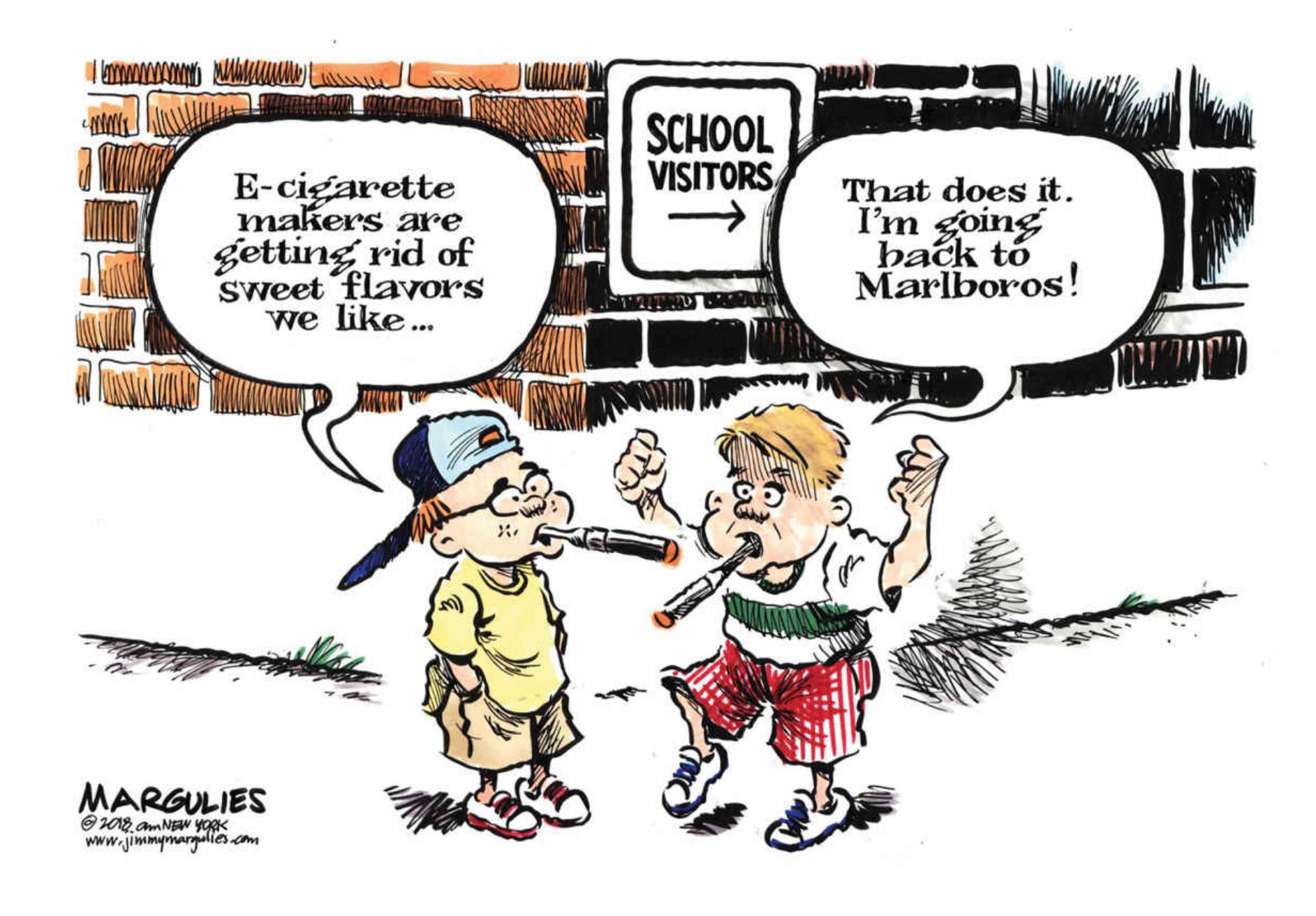

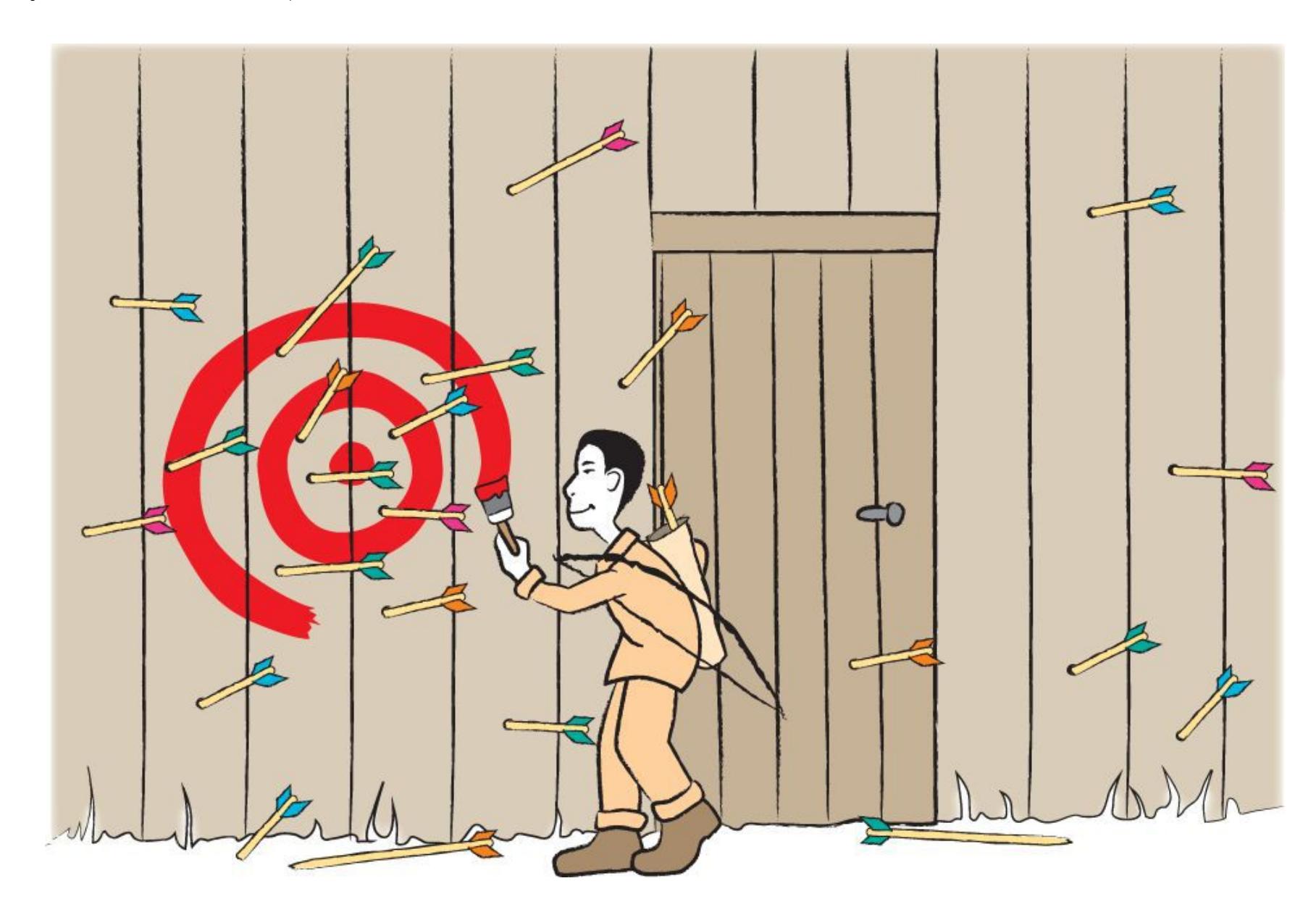

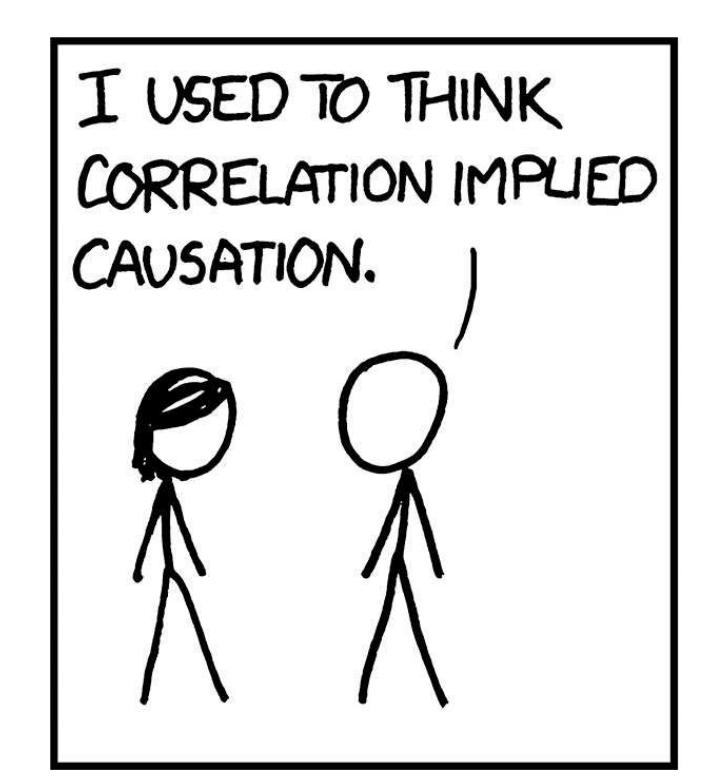

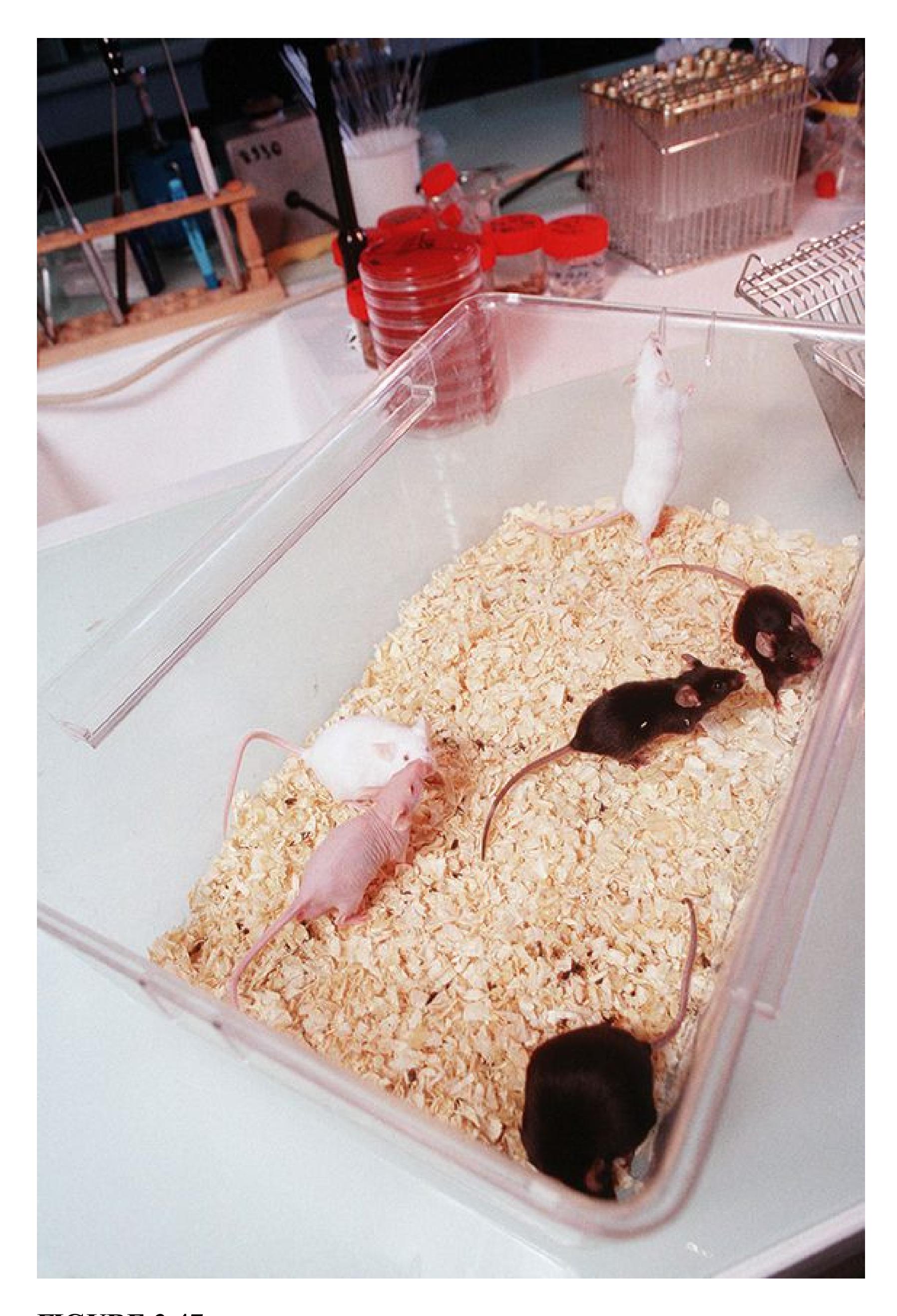

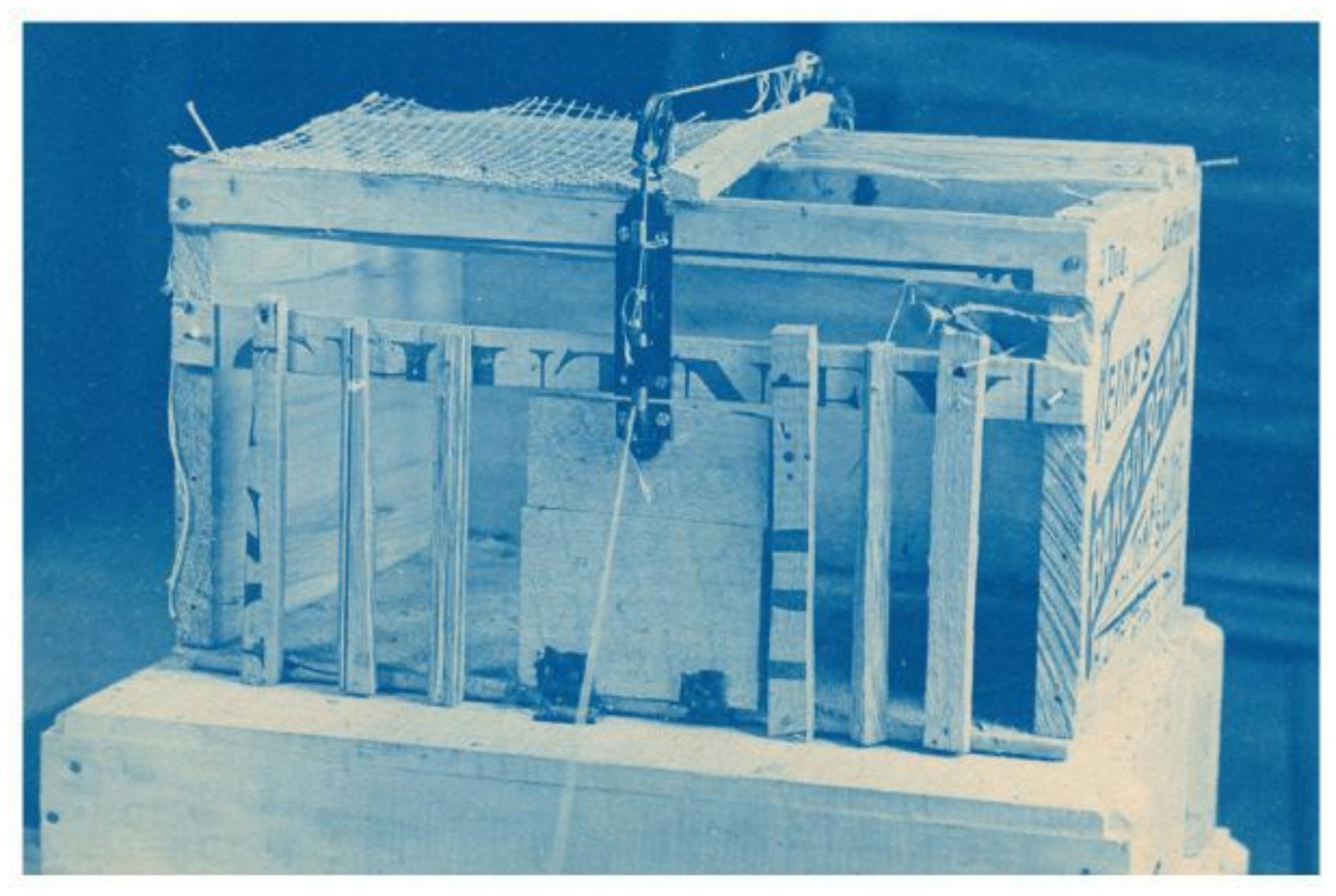

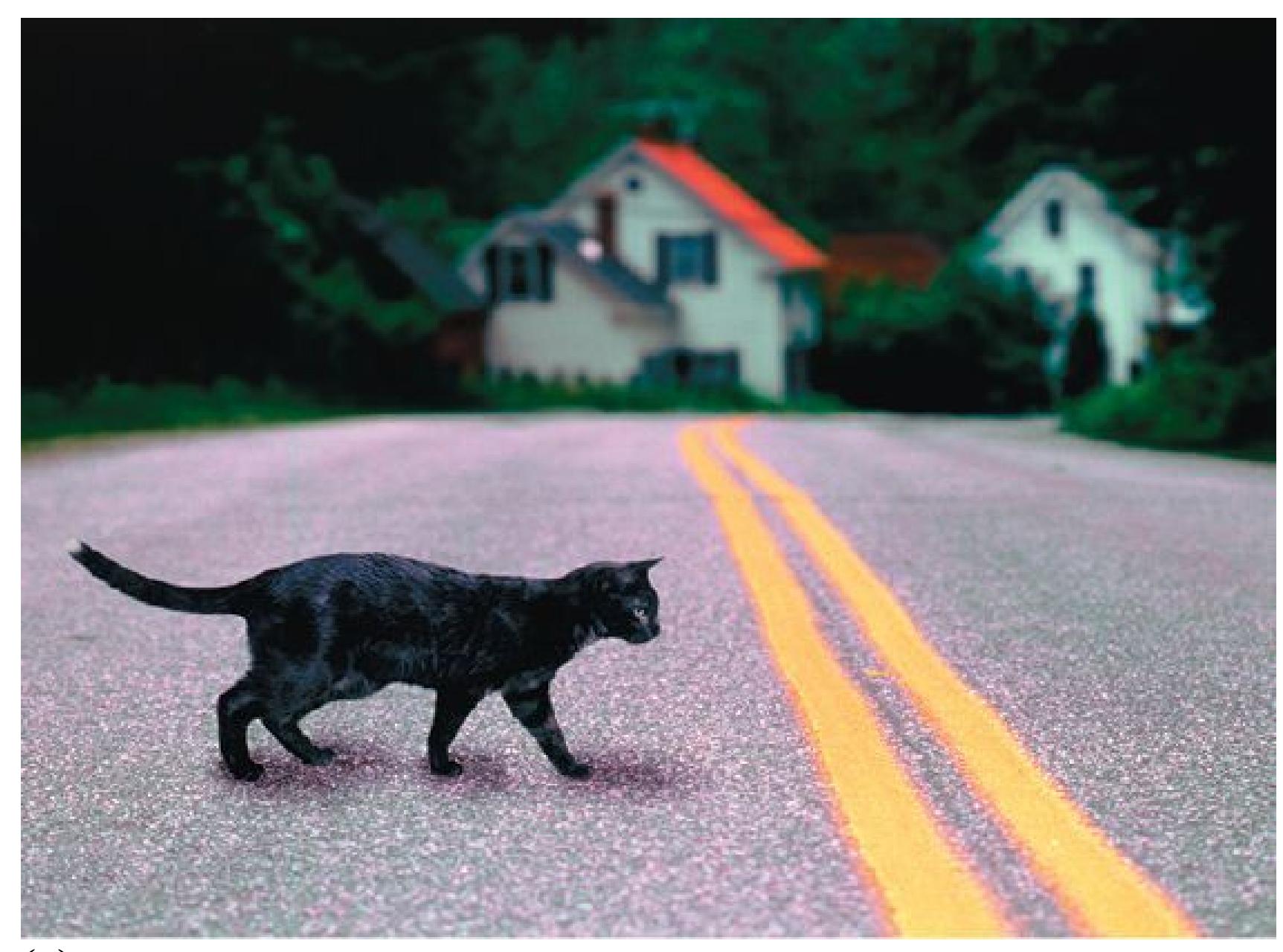

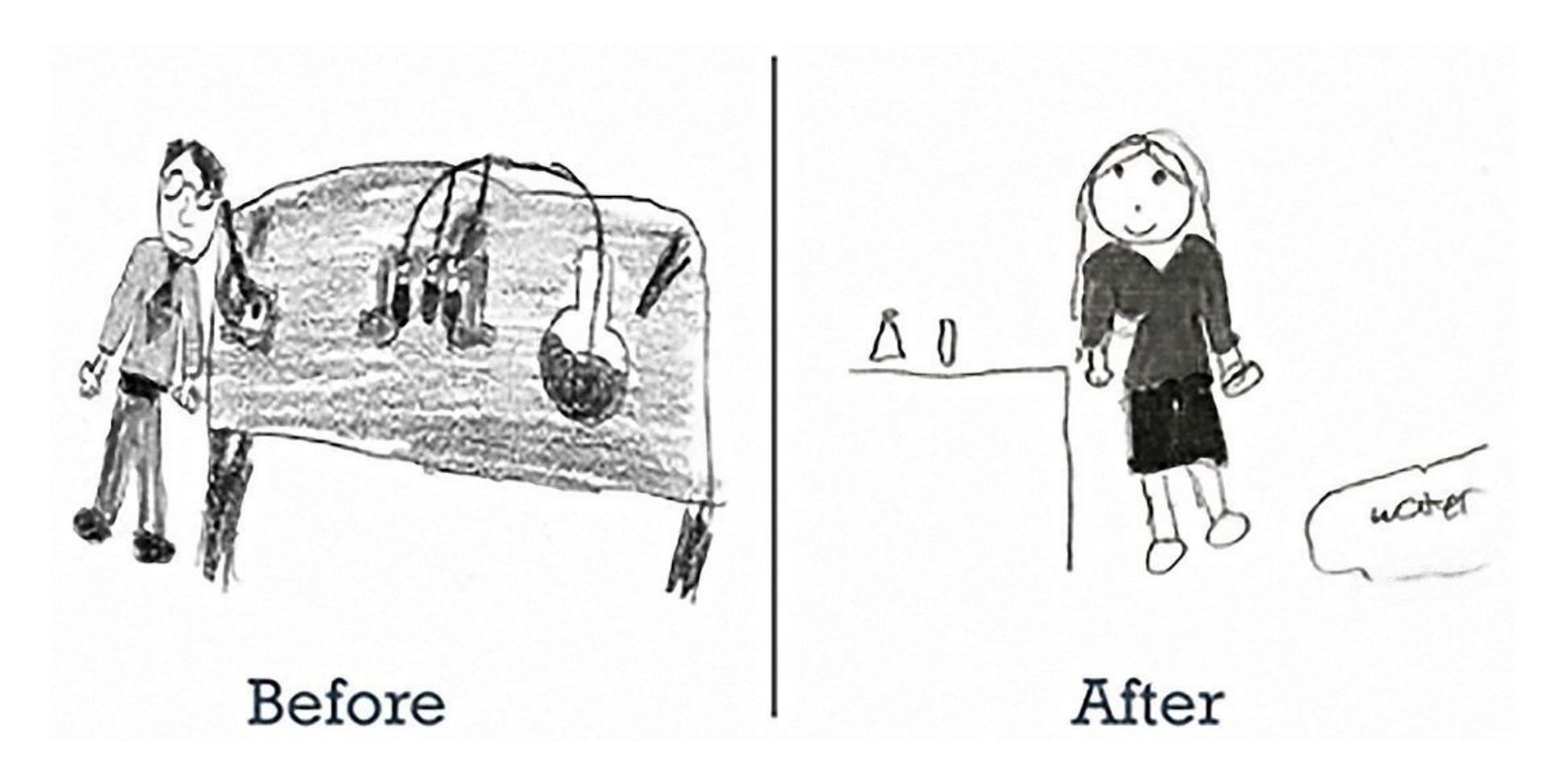

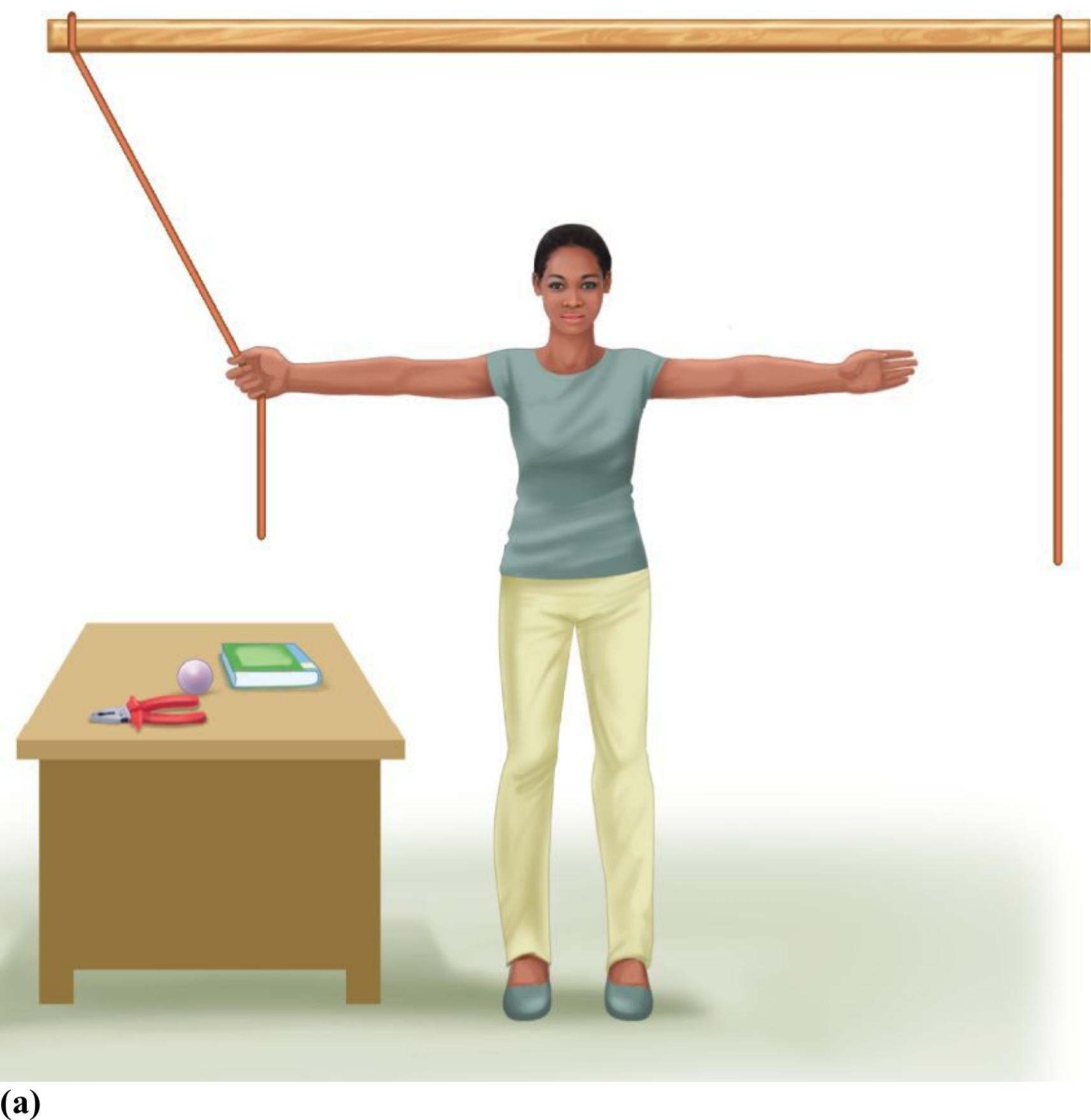

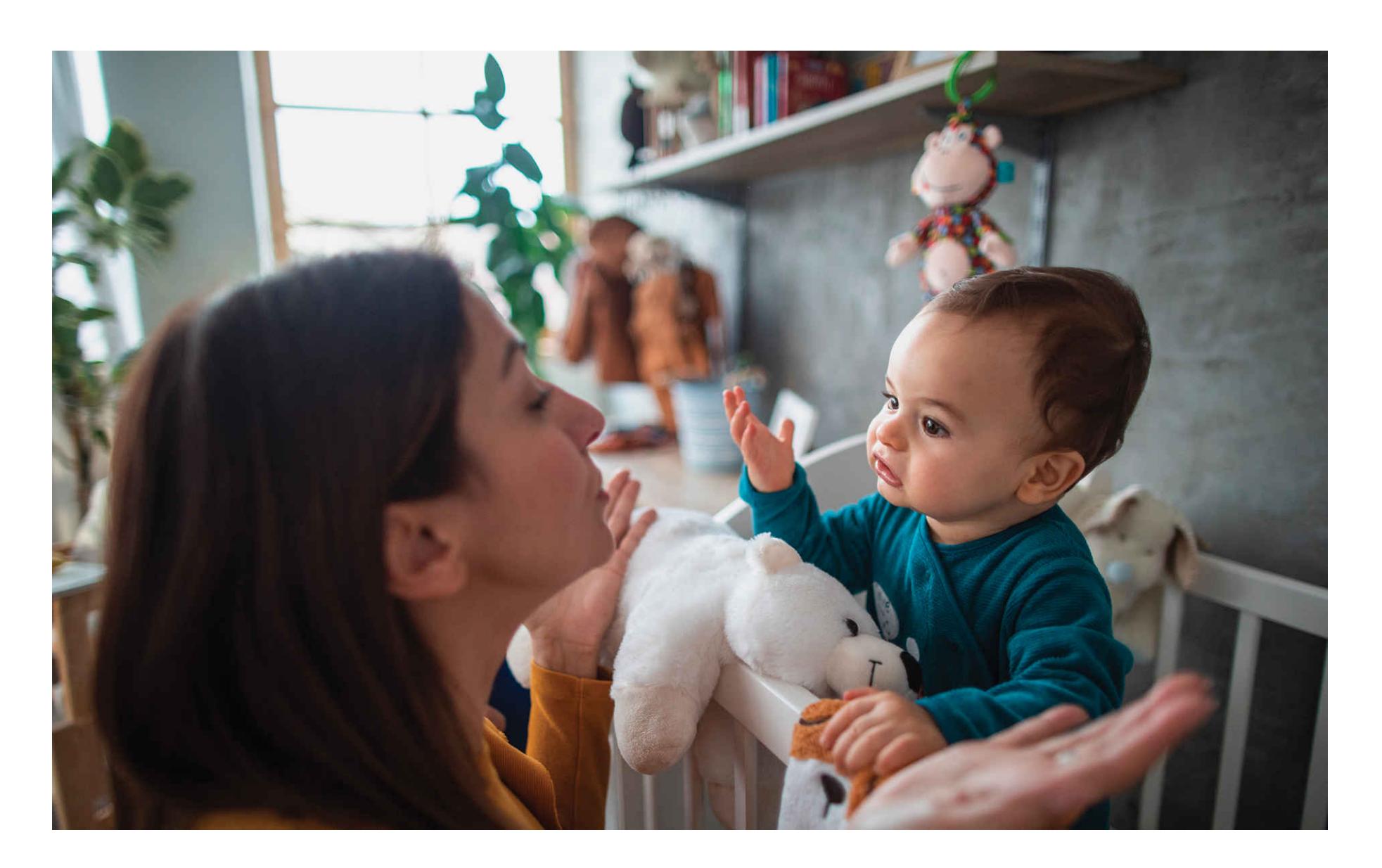

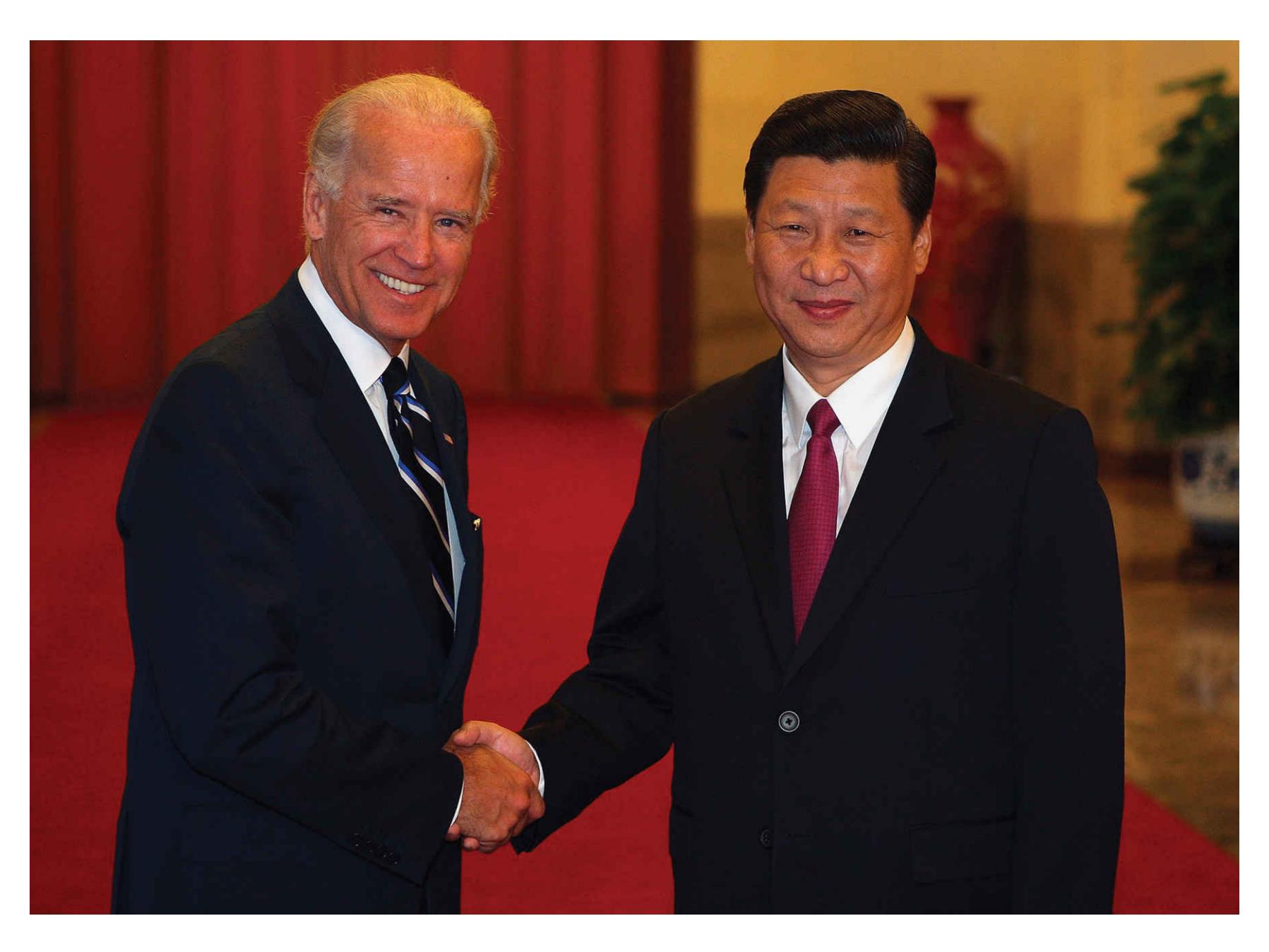

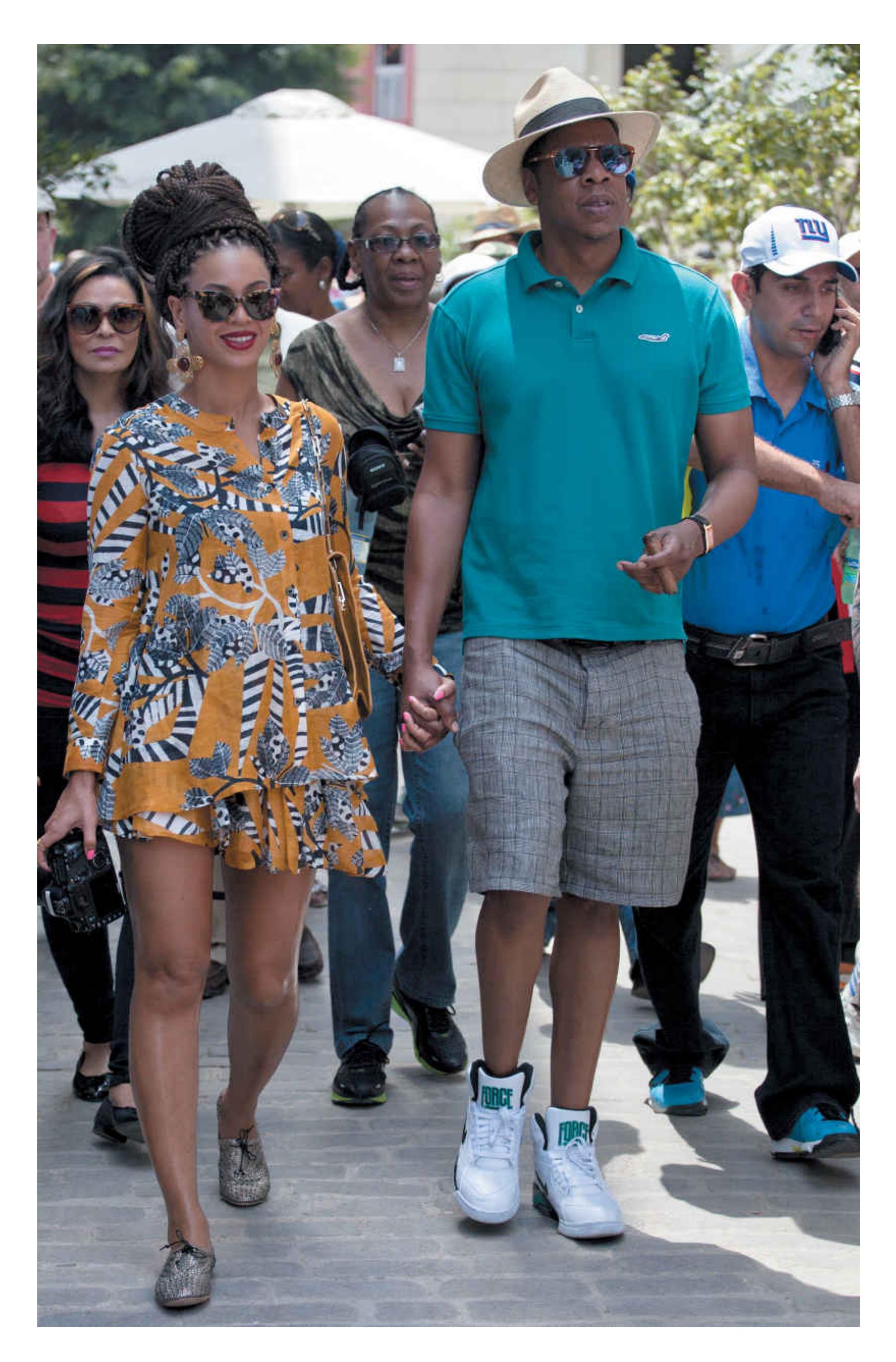

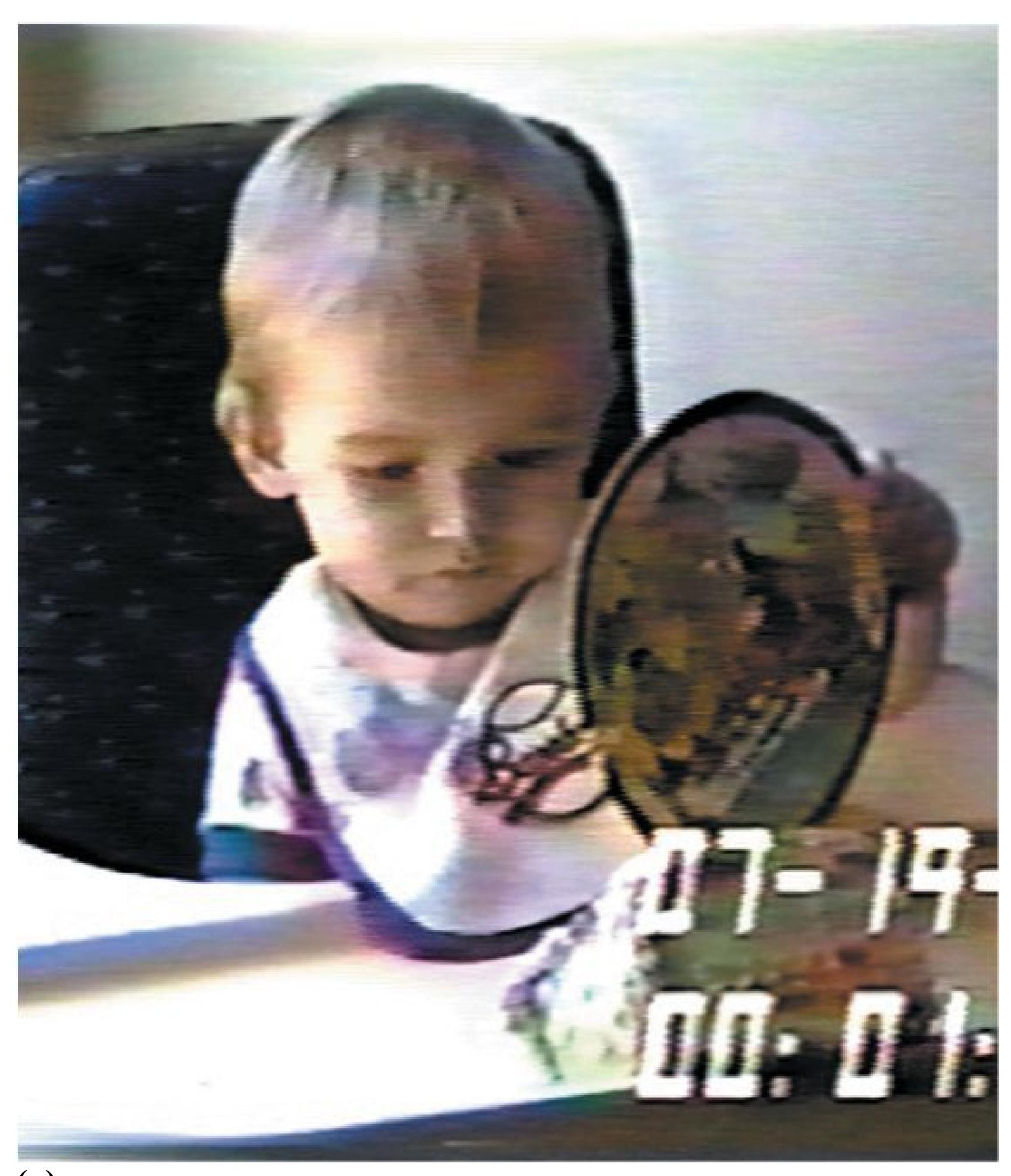

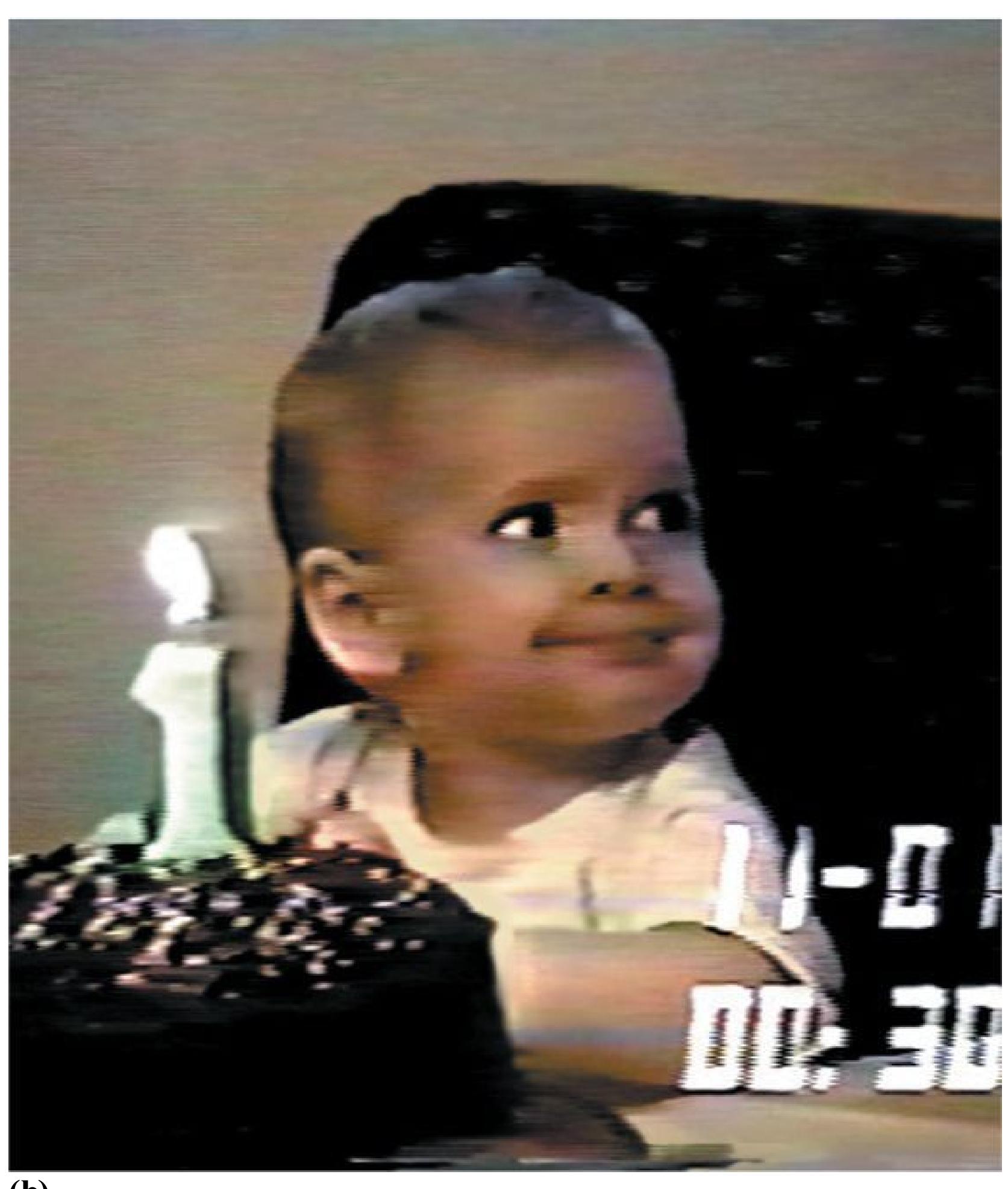

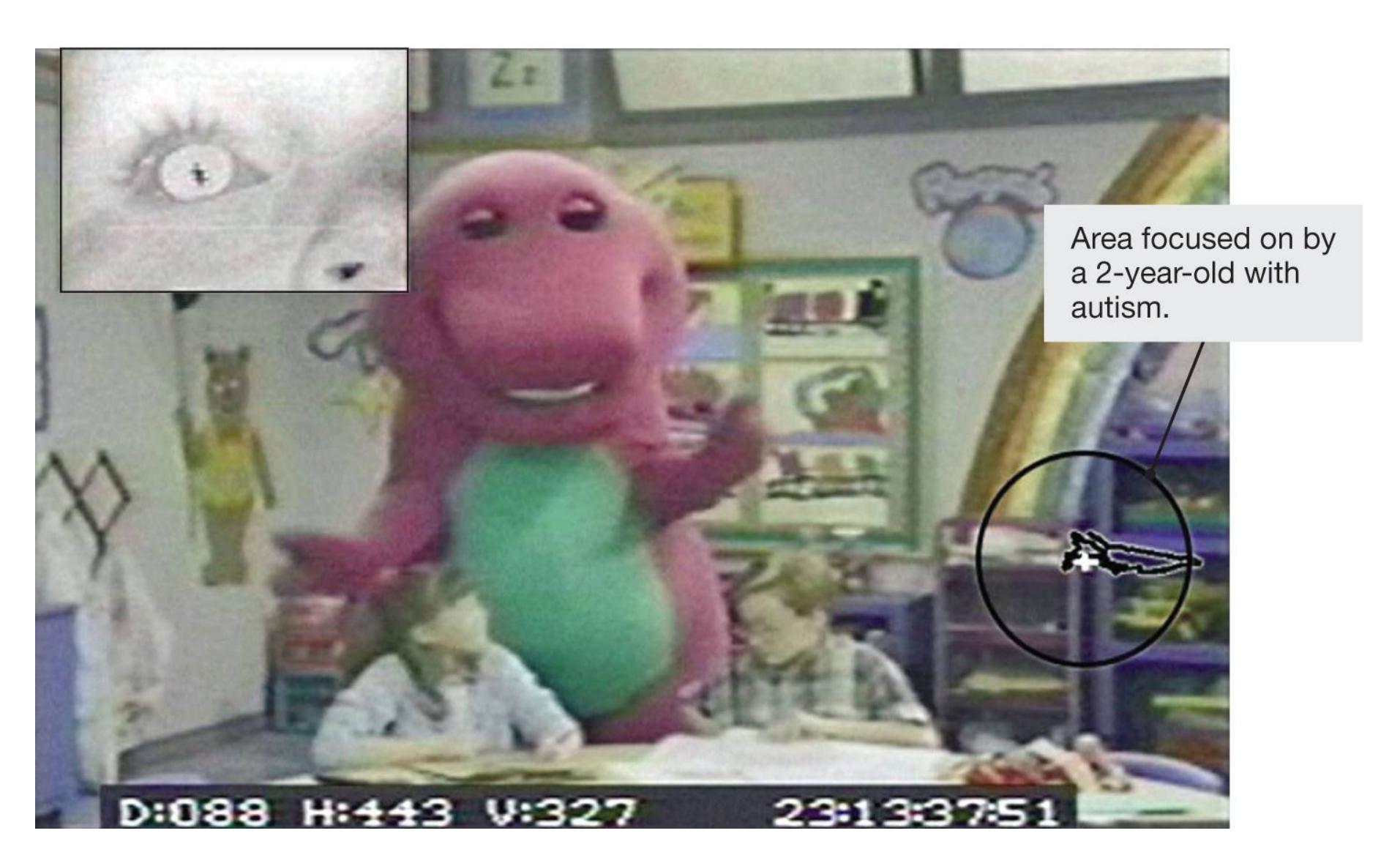

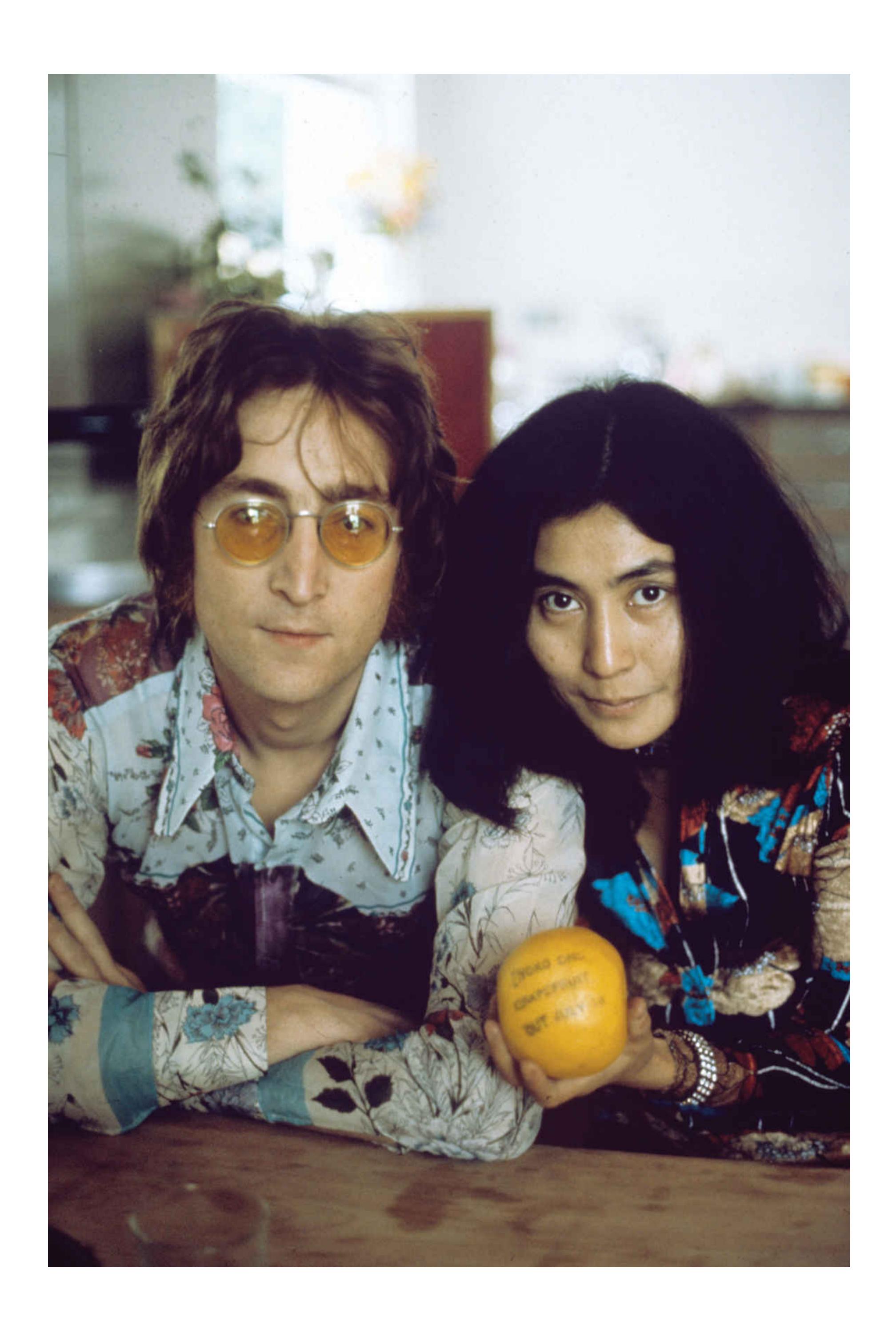

The media love a good story, and findings from psychological research are often provocative (**FIGURE 1.1**). Unfortunately, media reports can be distorted or even flat-out wrong. Throughout your life, as a consumer of psychological science, you will need to be skeptical of overblown media reports of "brand-new" findings obtained by "groundbreaking" research. With the rapid expansion of online information sharing and thousands of searchable research findings on just about any topic, you need to be able to sort through and evaluate the information you find in

order to gain a correct understanding of the phenomenon (observable thing) you are trying to investigate.

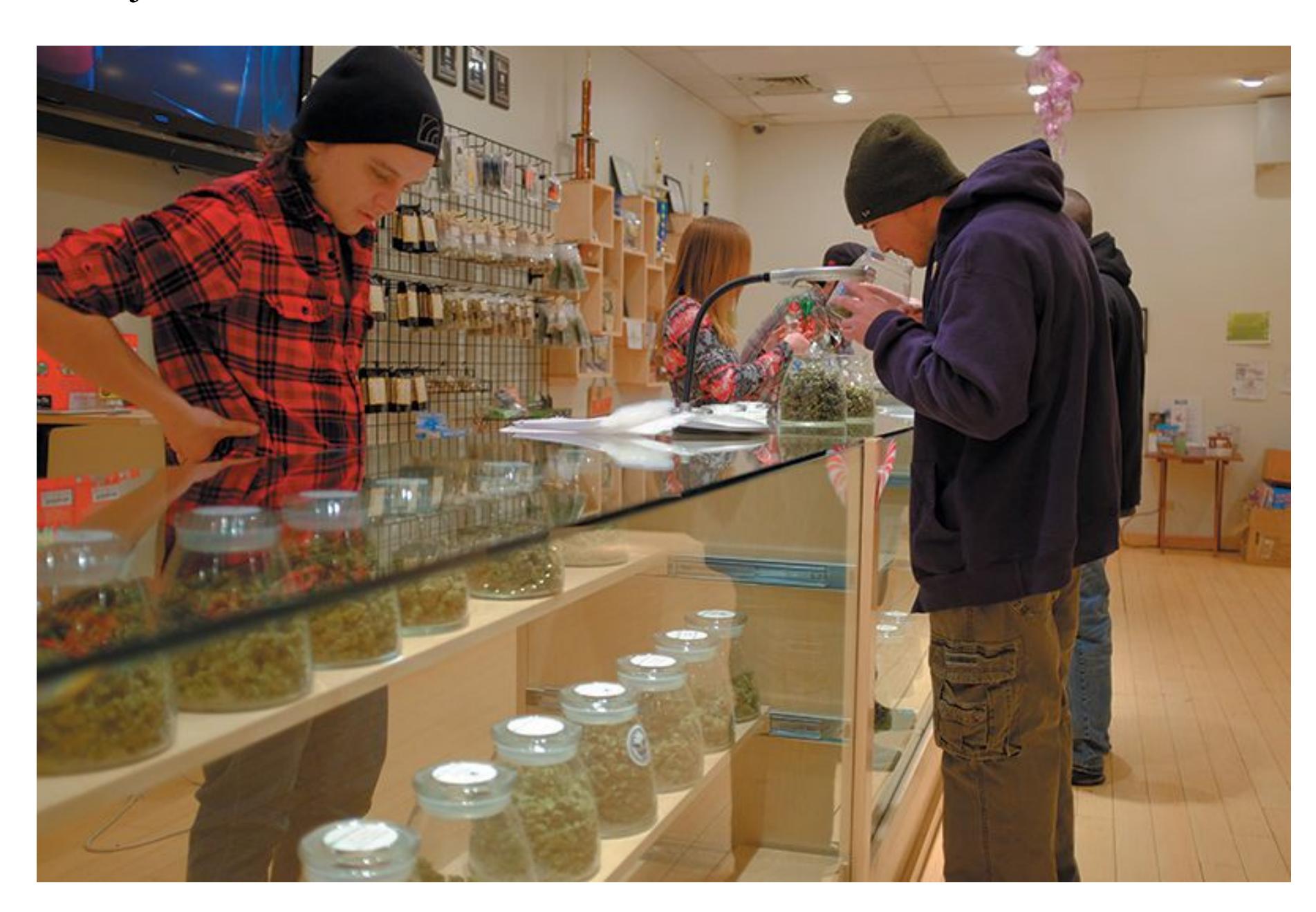

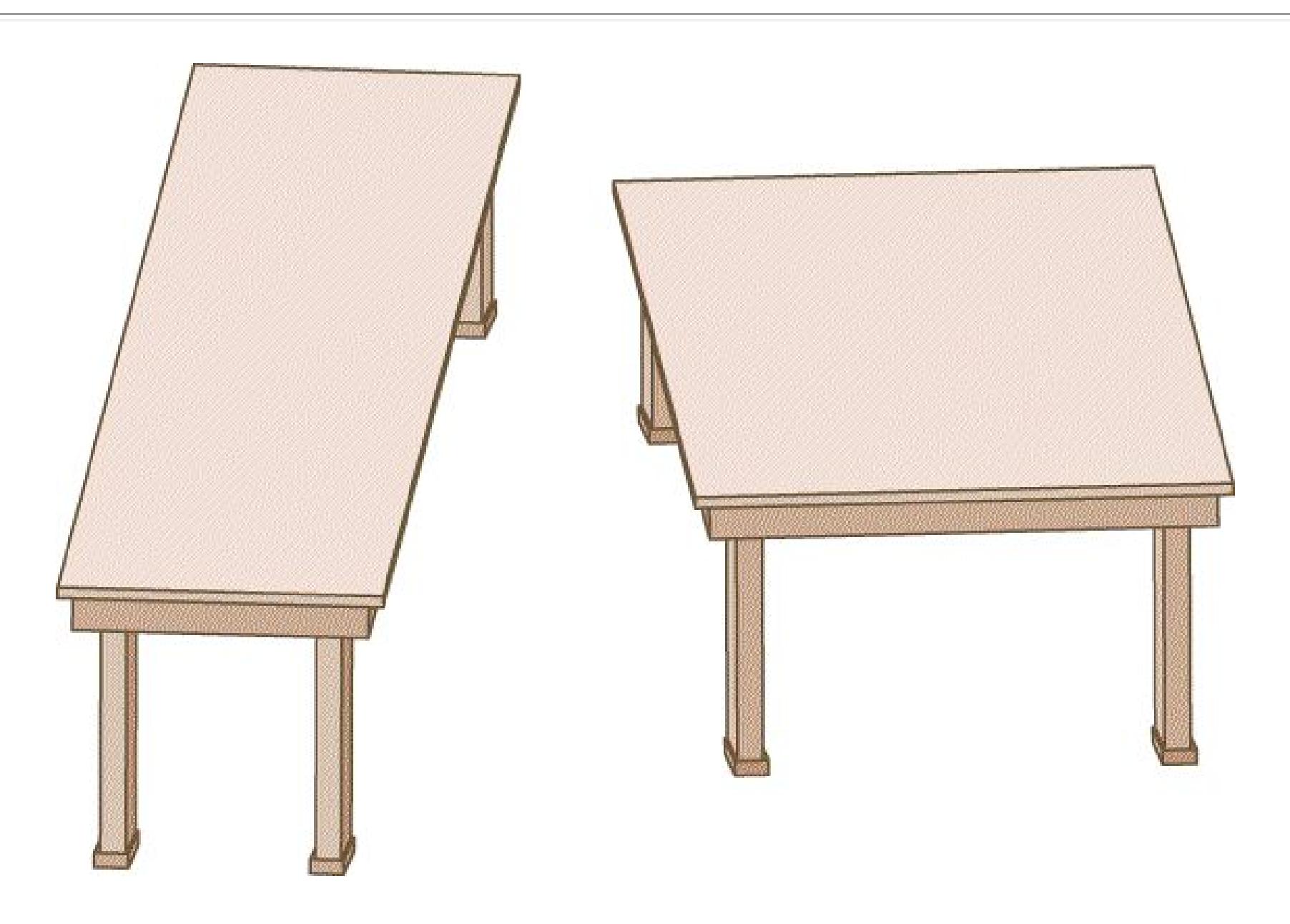

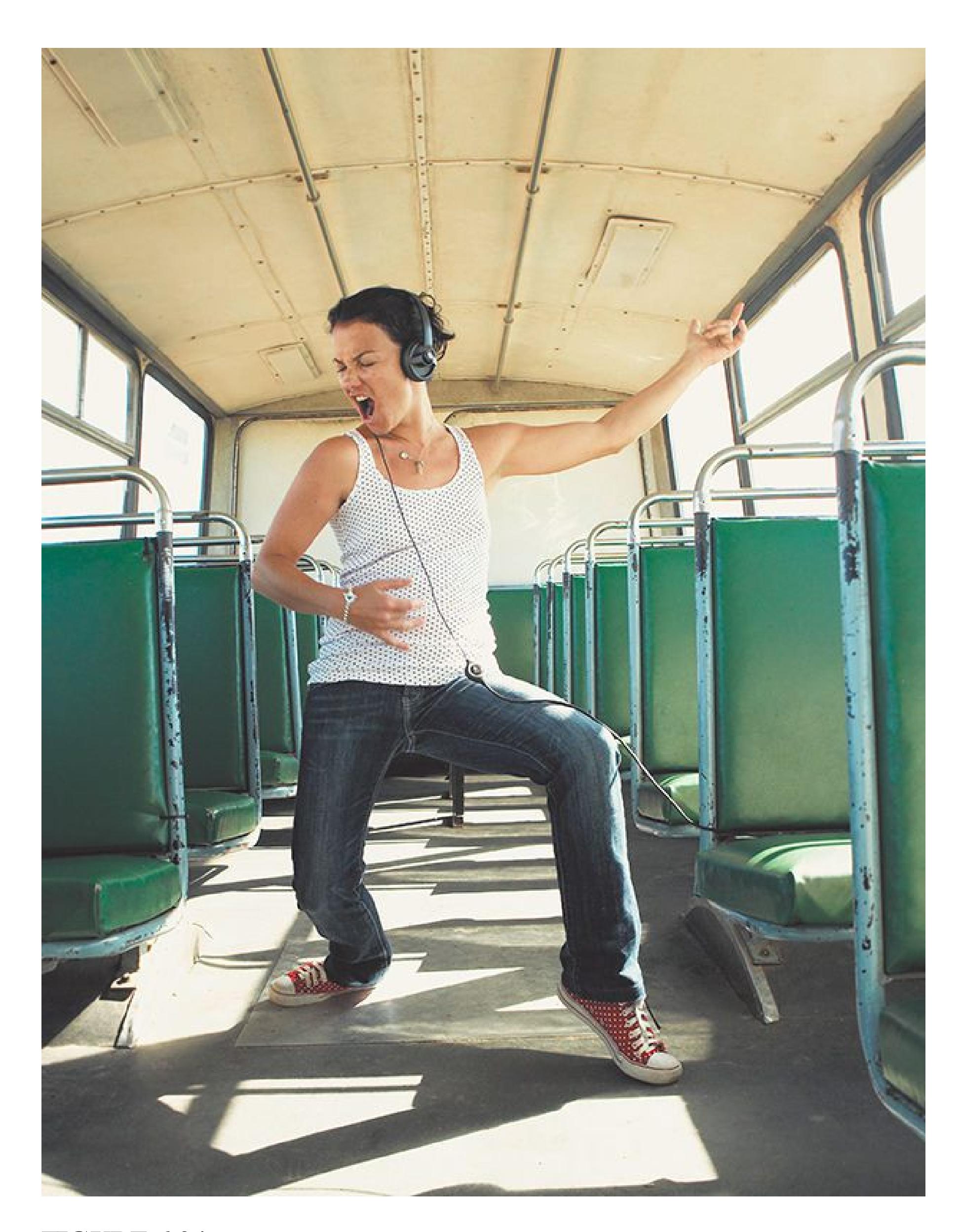

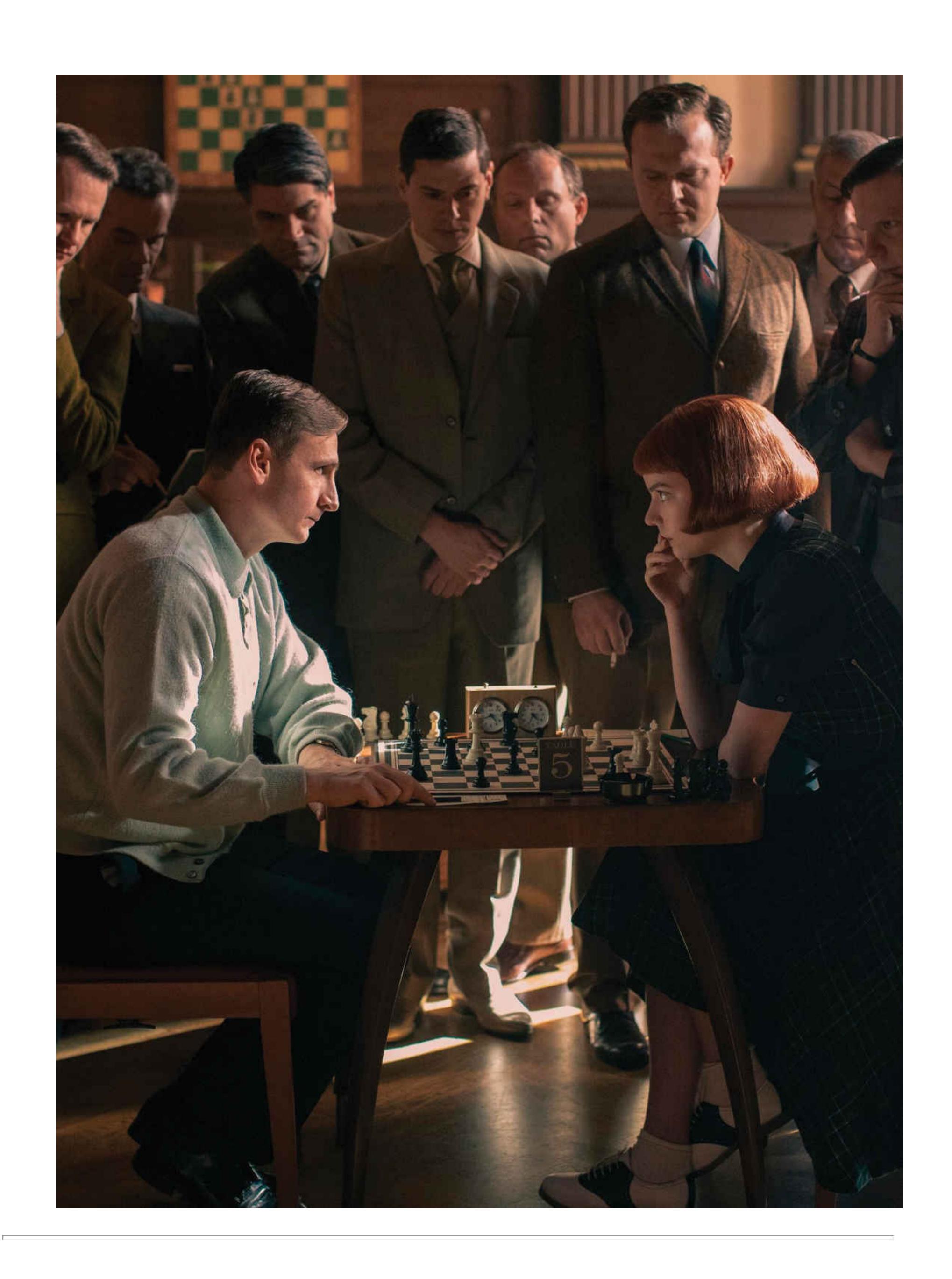

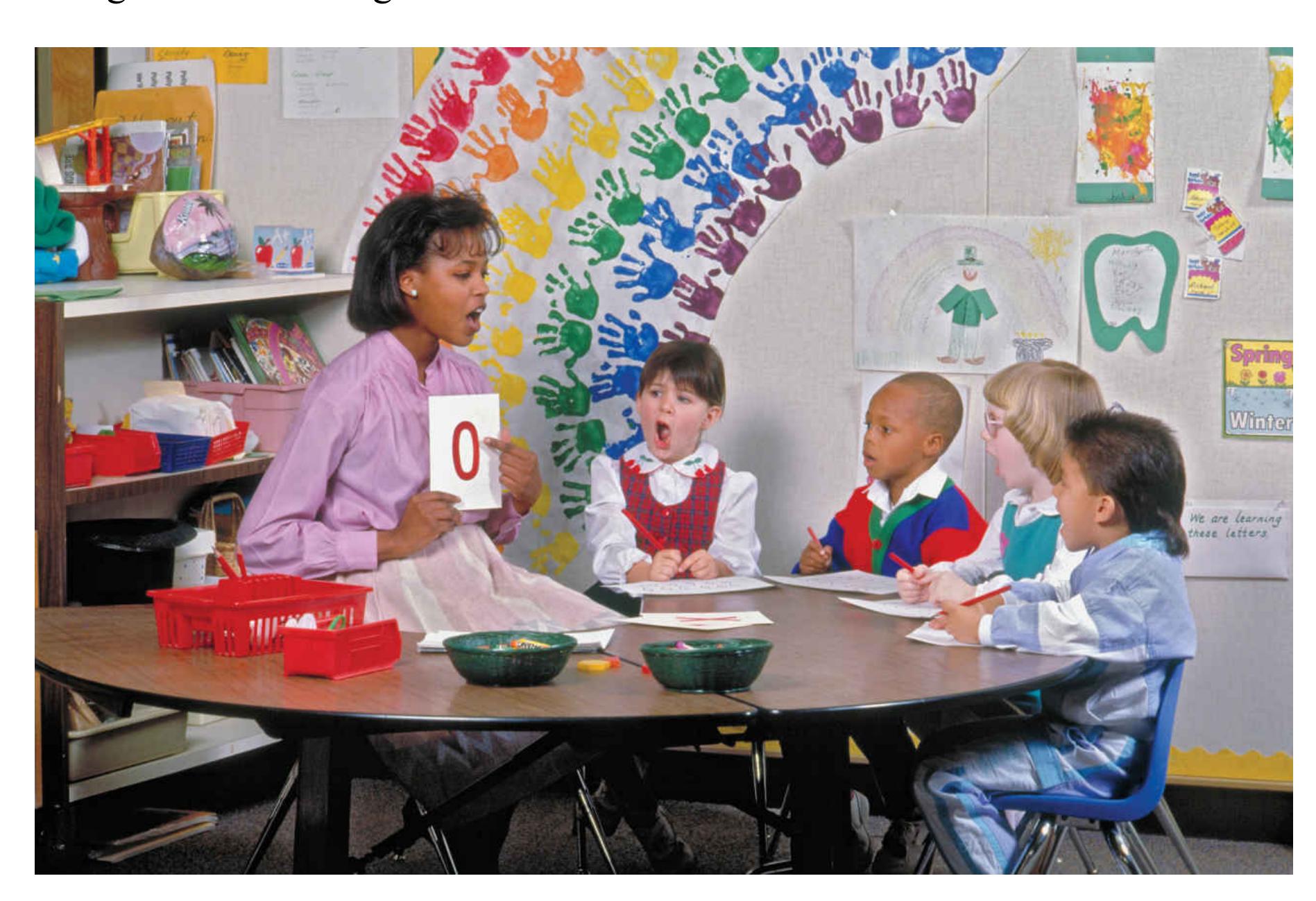

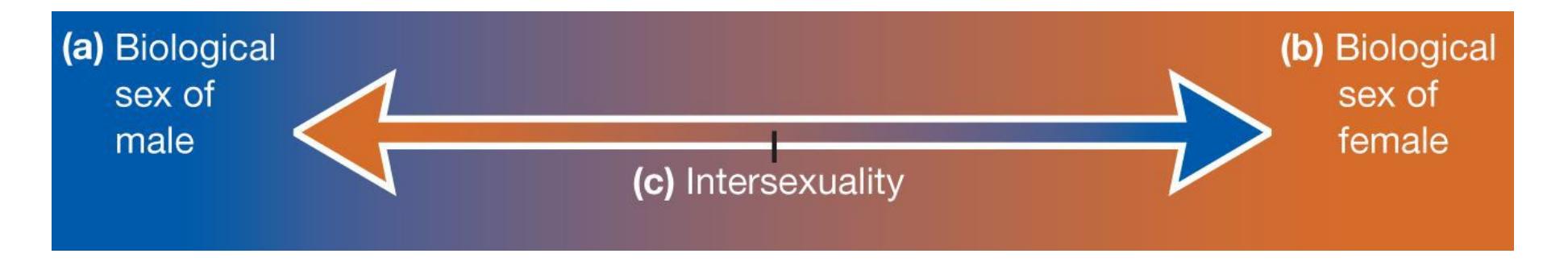

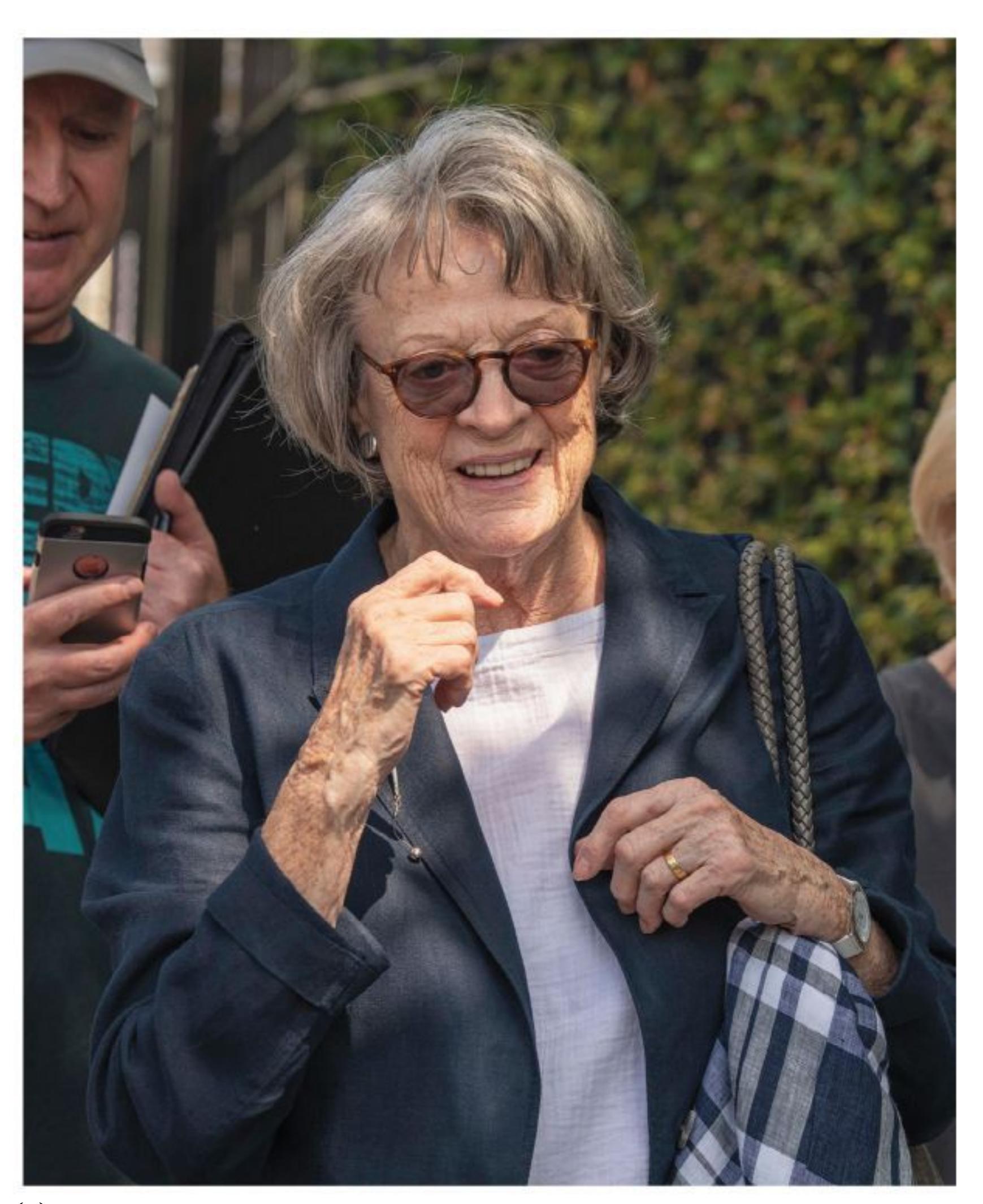

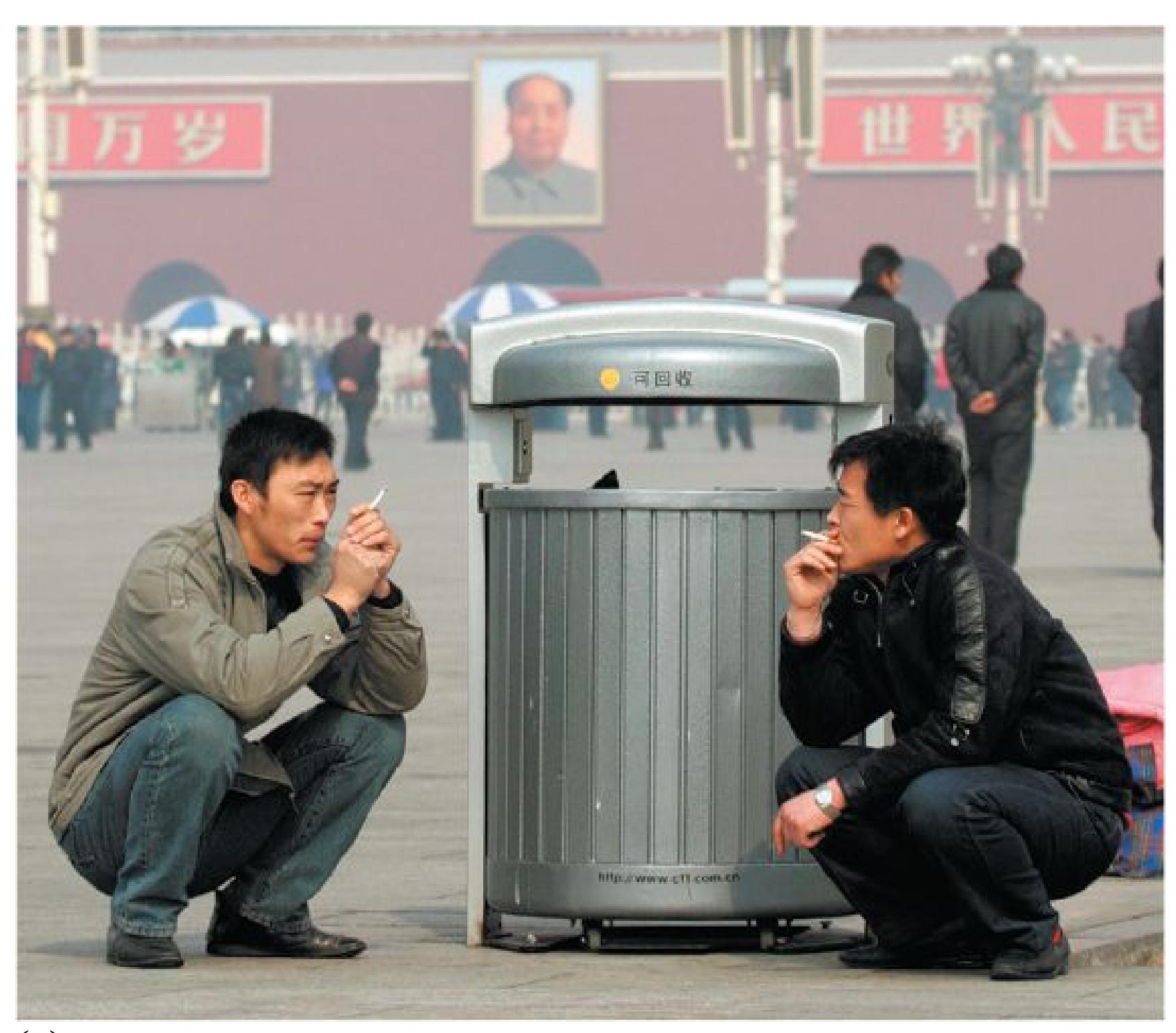

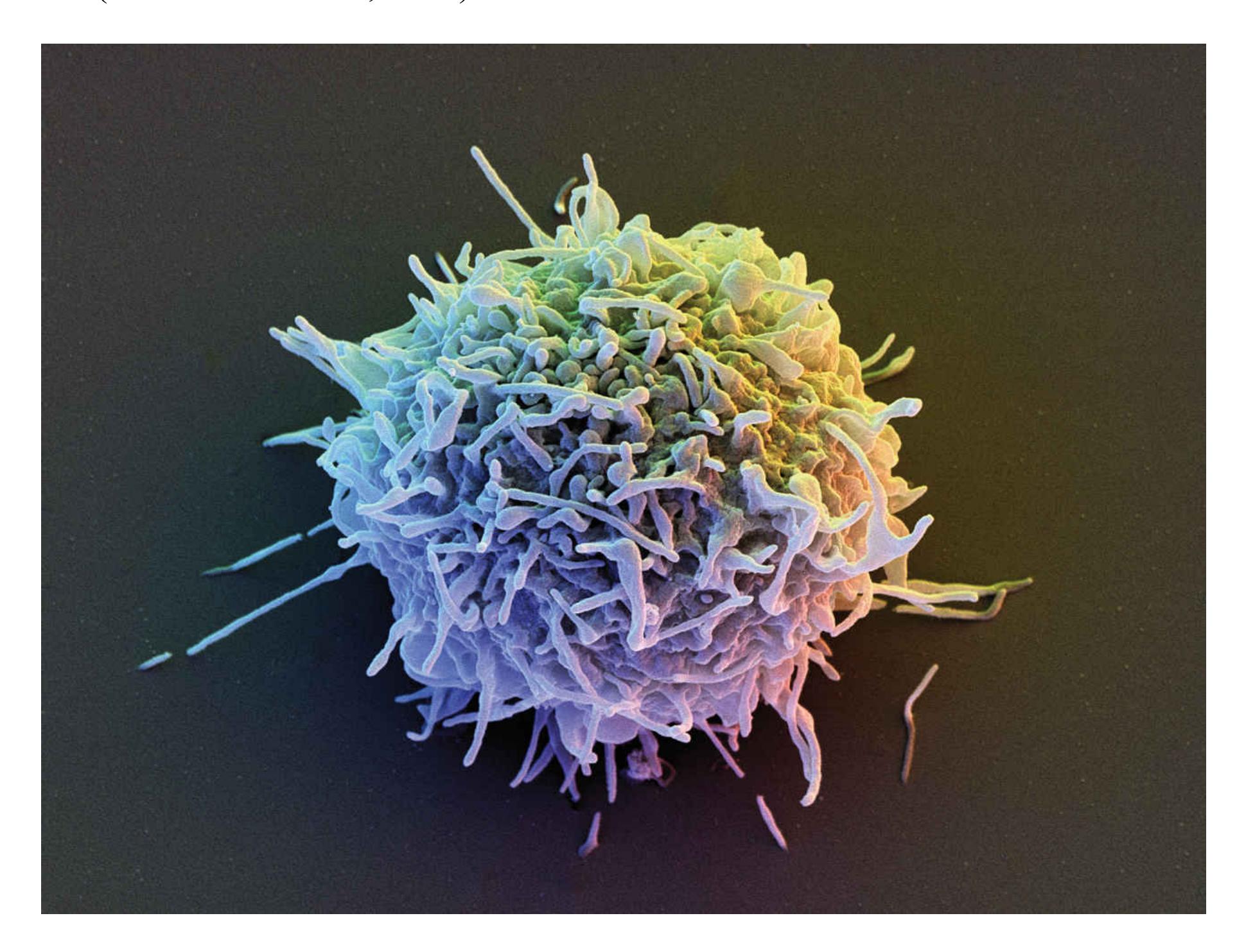

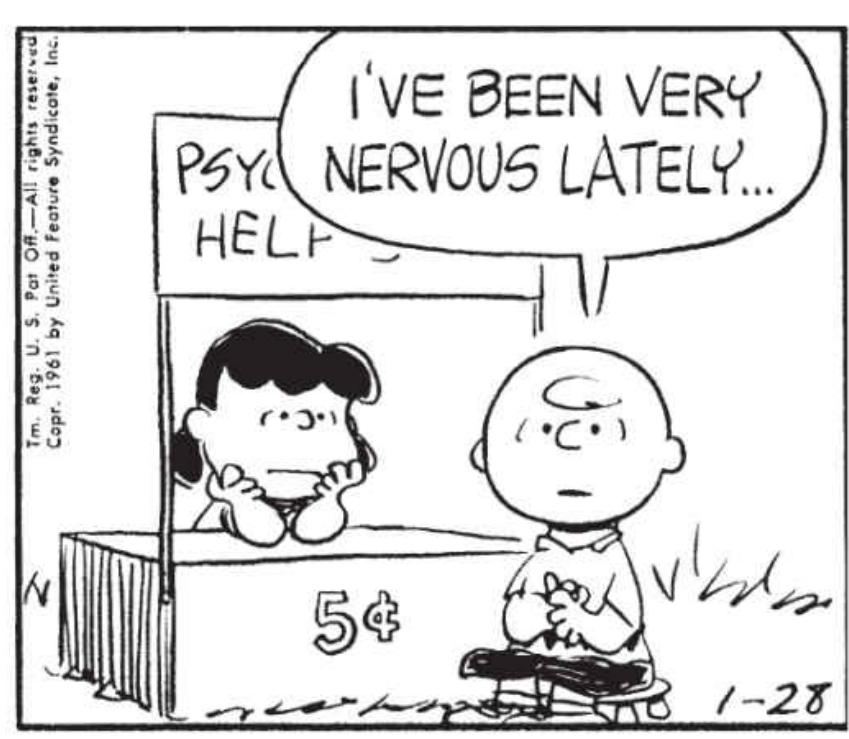

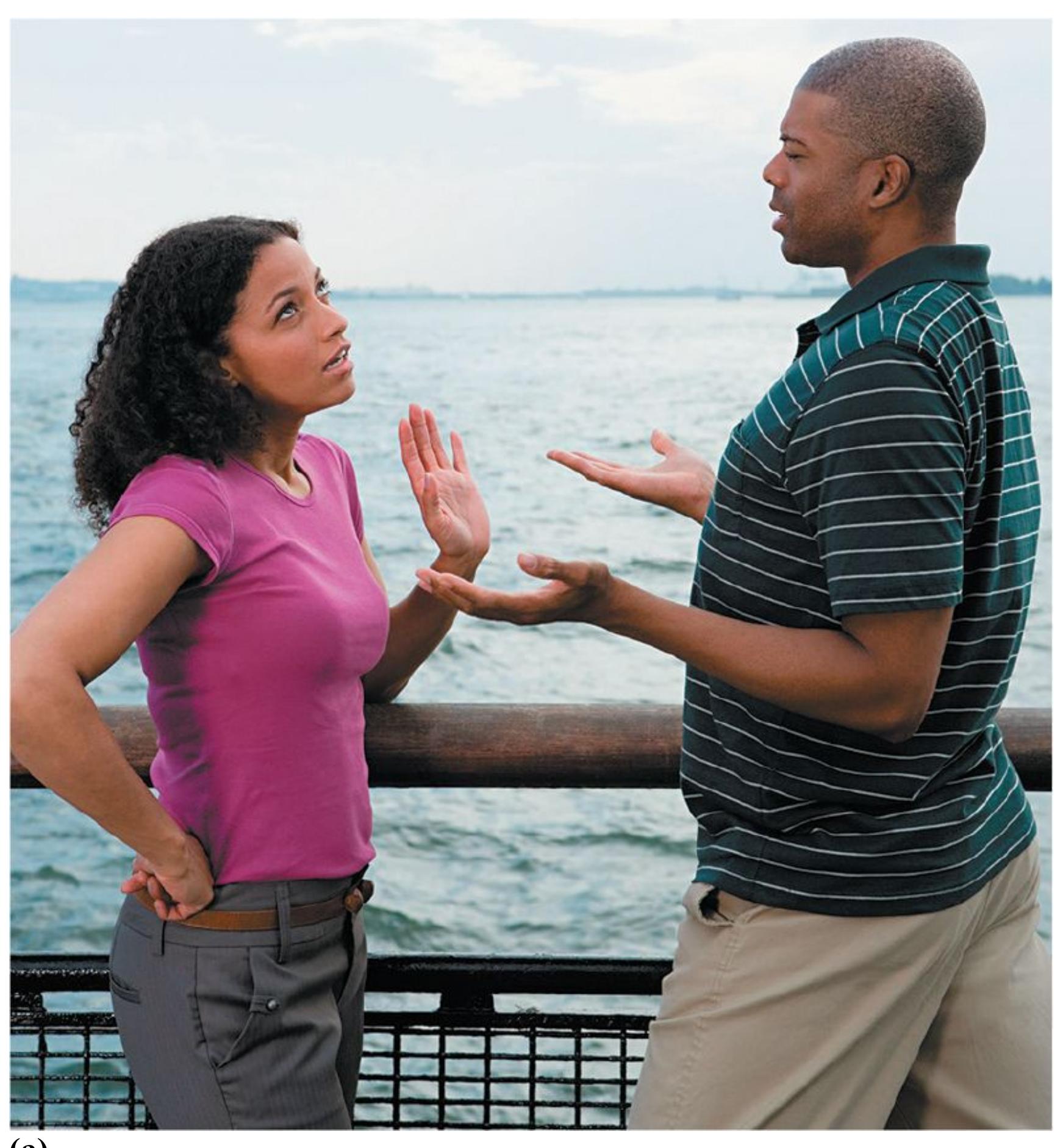

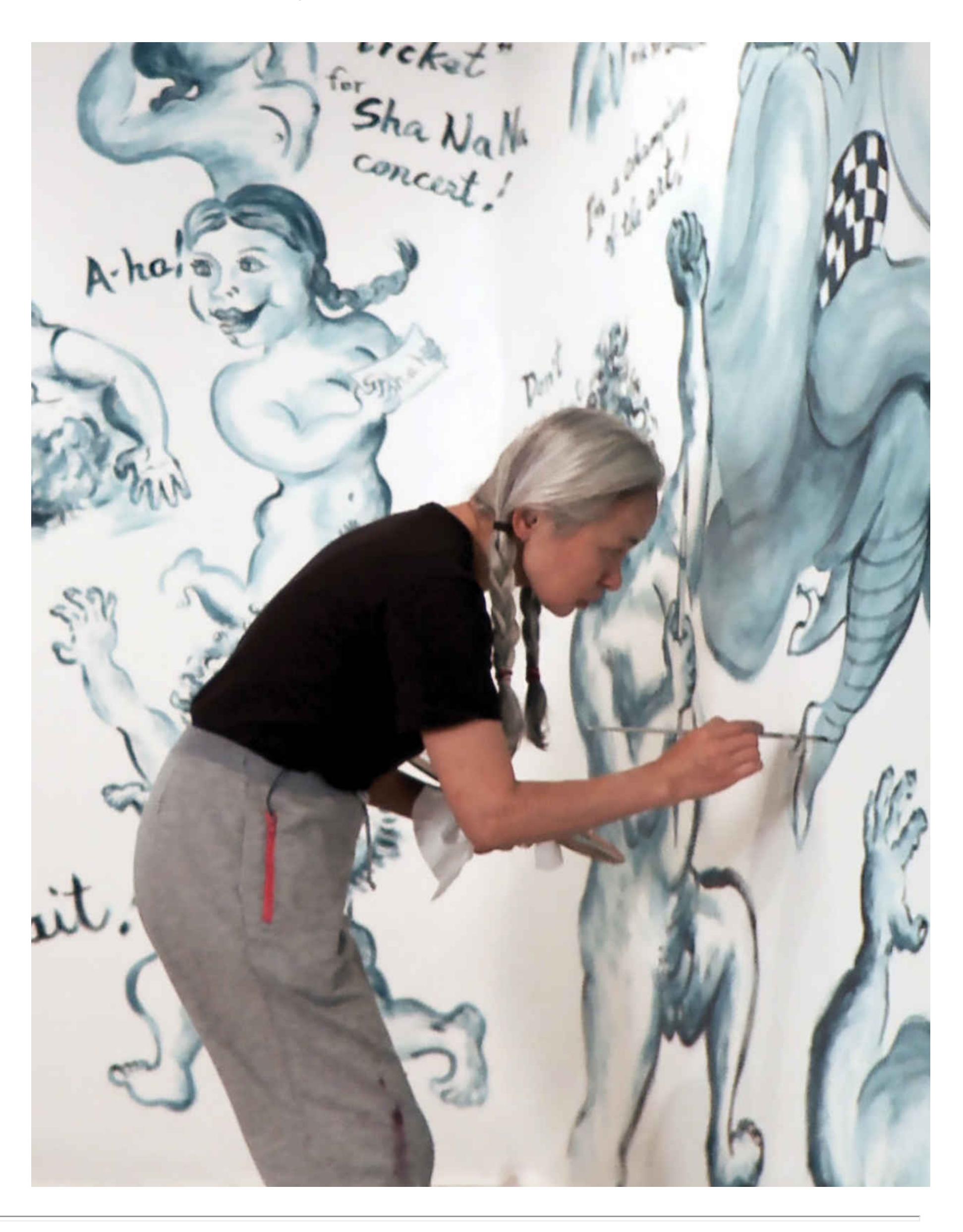

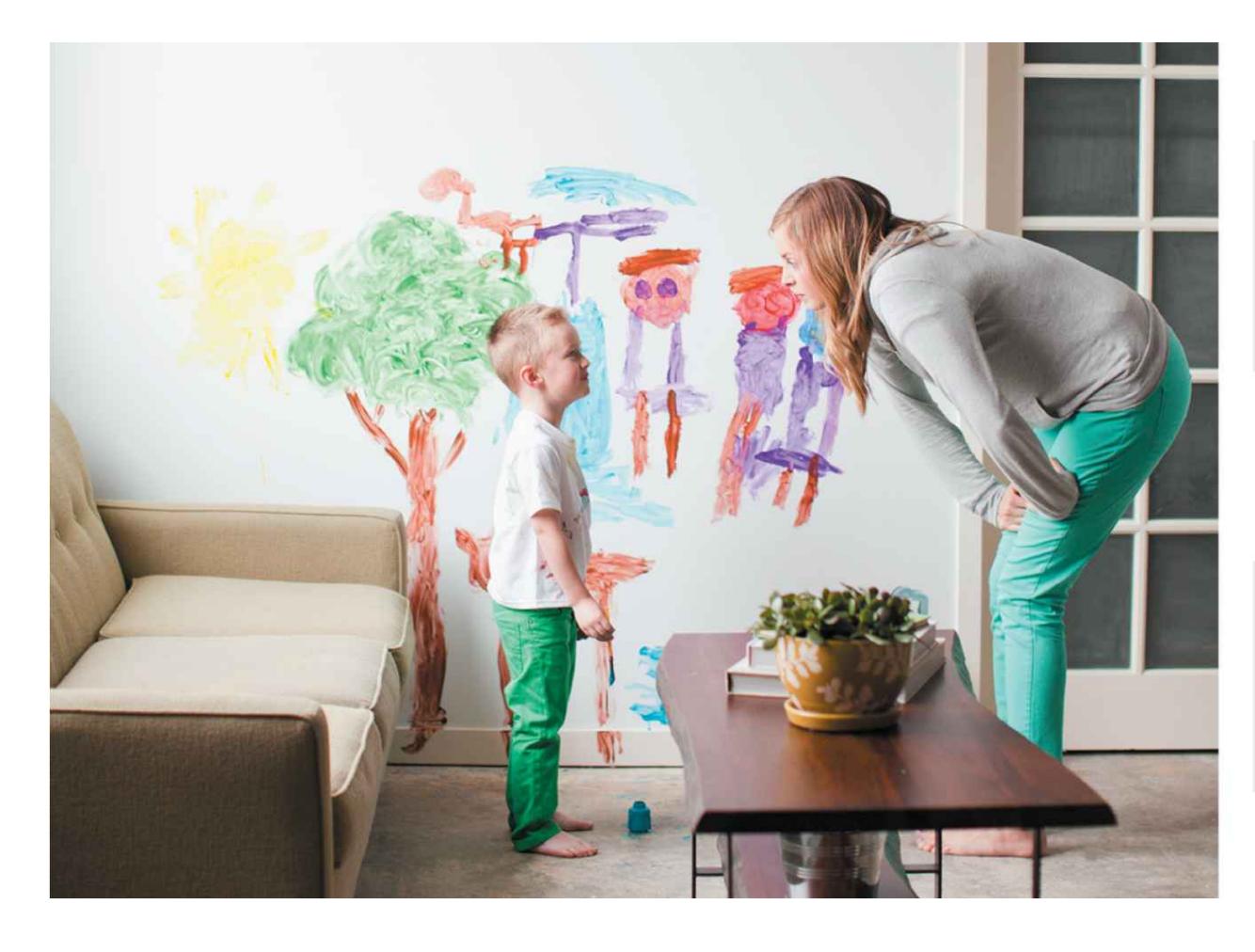

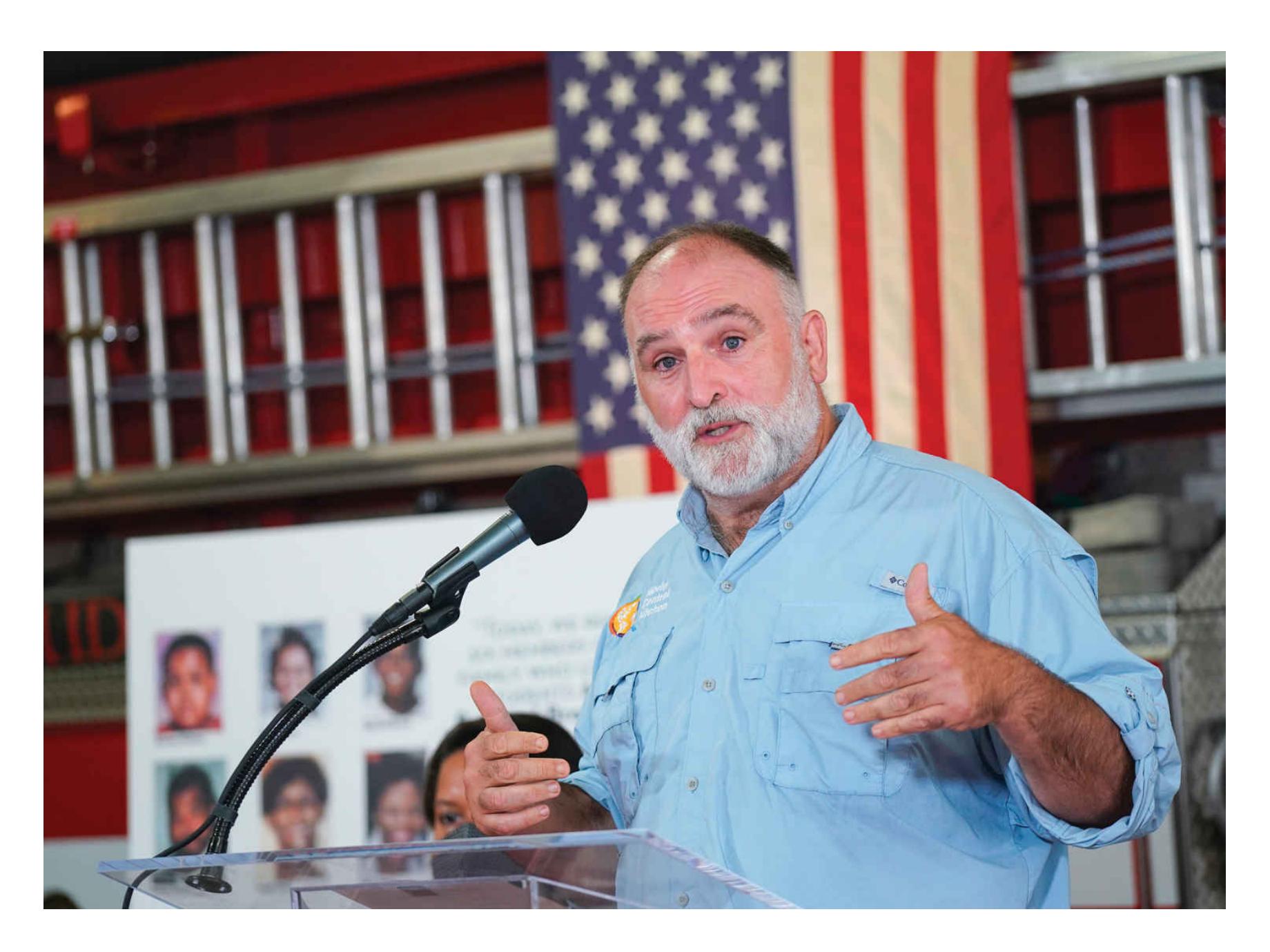

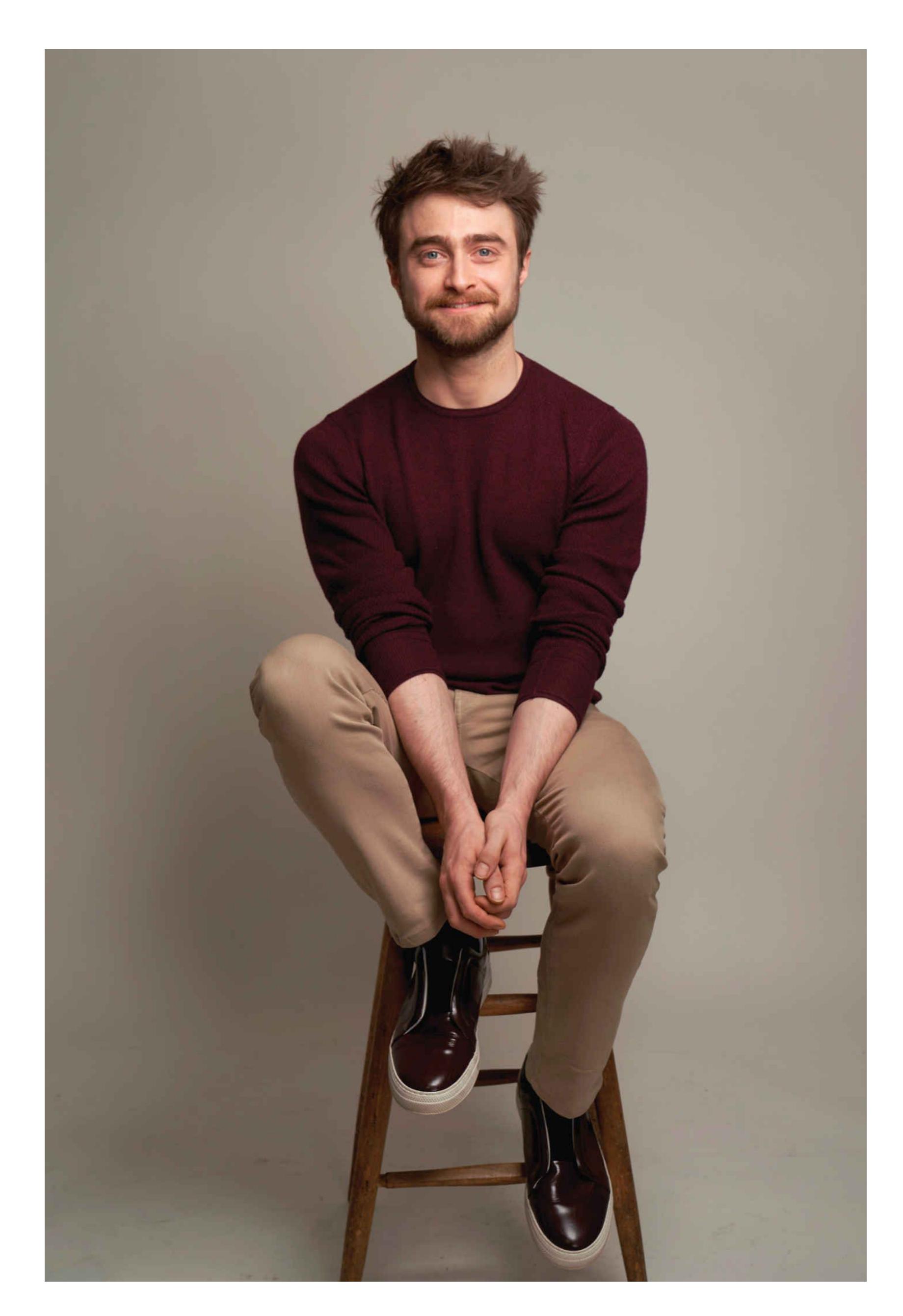

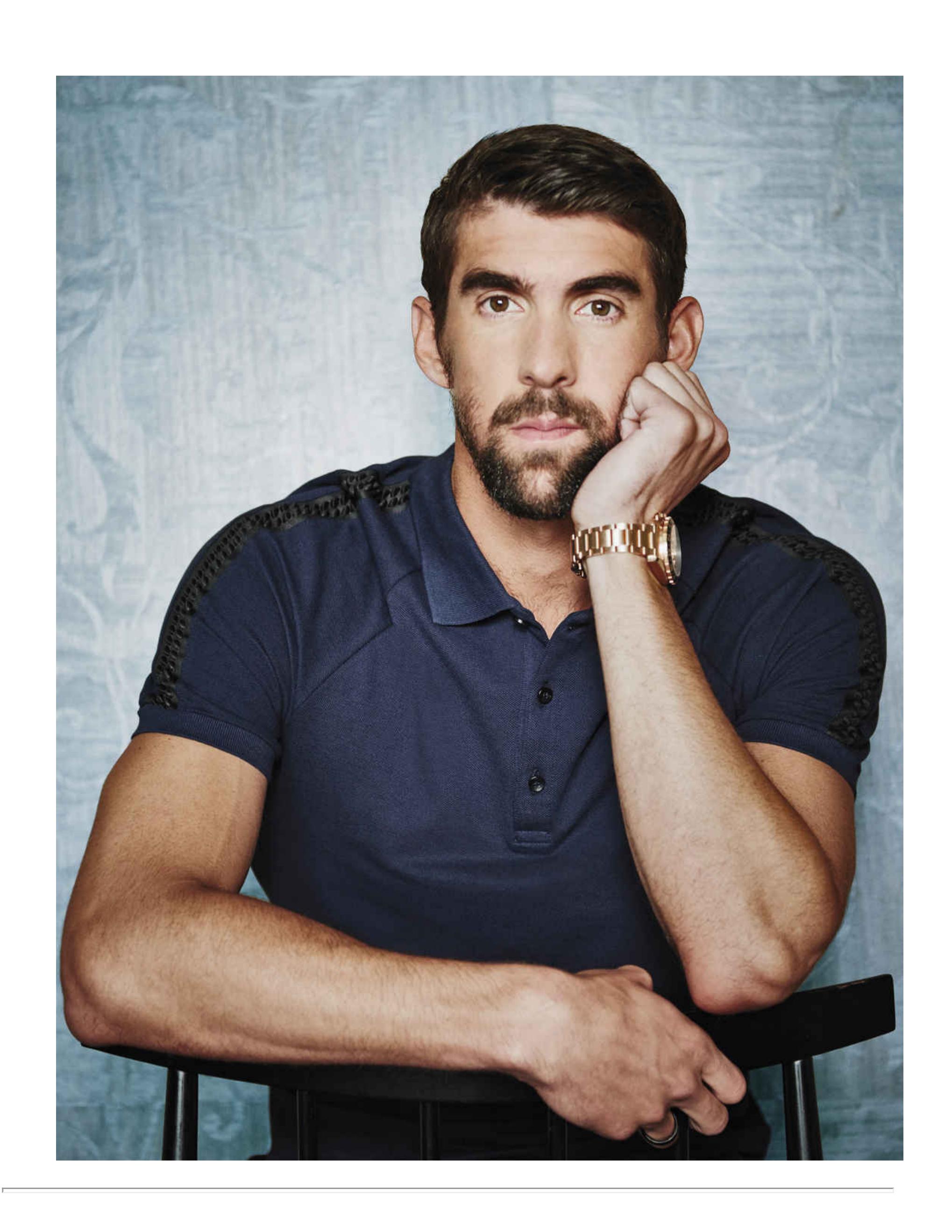

# FIGURE 1.1

# Psychology in the News

Psychological research is often in the news because the findings are intriguing and relevant to people's lives.

One of the hallmarks of a good scientist—or a savvy consumer of scientific research—is *amiable skepticism*. This trait combines openness and wariness. An amiable skeptic remains open to new ideas but is wary of new "scientific findings" when good evidence and sound reasoning do not seem to support them. An amiable skeptic develops the habit of carefully weighing the facts when deciding what to believe. Thinking in this way—systematically questioning and evaluating information using well-supported evidence—is called [critical thinking.](#page-11-0)

Critical thinking is useful in every aspect of your life. It is also important in all fields of study throughout the humanities and the sciences. In fact, psychological science itself sheds light on the way people typically think when they encounter information. Many decades of psychological research have shown that people's intuitions are often wrong, and they tend to be wrong in predictable ways that make critical thinking very difficult. Through scientific study, psychologists have discovered types of situations in which common sense fails and biases influence people's judgments.

Being aware of your own biases in thinking will also help you do better in your classes, including this one. Many students have misconceptions about psychological phenomena before they have taken a psychology course. The psychologists Patricia Kowalski and Annette Kujawski Taylor (2004) found that students who employ critical thinking skills complete an introductory course with a more accurate understanding of psychology than students who complete the same course but do not employ critical thinking skills. As you read this book, you will benefit from the critical thinking skills that you will learn about and get to practice. These skills are the most valuable lessons from this course, and you will bring them to your other classes, your workplace, and your everyday life.

The Material Design

Understanding the Pursuit of Goals

by Elliot Berkman, Ph.D.

Don't believe the hype—there's a catch to mental skills training programs.

Published on December 31, 2013 by Dr. Elliot T. Berkman in The Motivated Brain

The recent

[proliferation](url) of commercial online "brain-training" services that promise to enhance

intelligence and other cognitive abilities is understandable: Who wouldn't want to be smarter and have

greater working memory and [inhibitory control](url)? Seeing the potential for low-cost and reliable

measurement of performance, some corporations have begun using similar tools to assess potential

hire and evaluate employees ("[people analytics](url)"). No doubt there is some amount of benefit to be

gained on both fronts. After all, people have an amazing capacity to develop expertise with practice in a

huge range of skills (think video games, driving, or crosswords), and it is an open secret that qualitative

interviews, the dominant tool currently used for evaluating new hires, are [subject](url) to [bias](url) and [don't](url)

[predict](url) job performance in the first place.

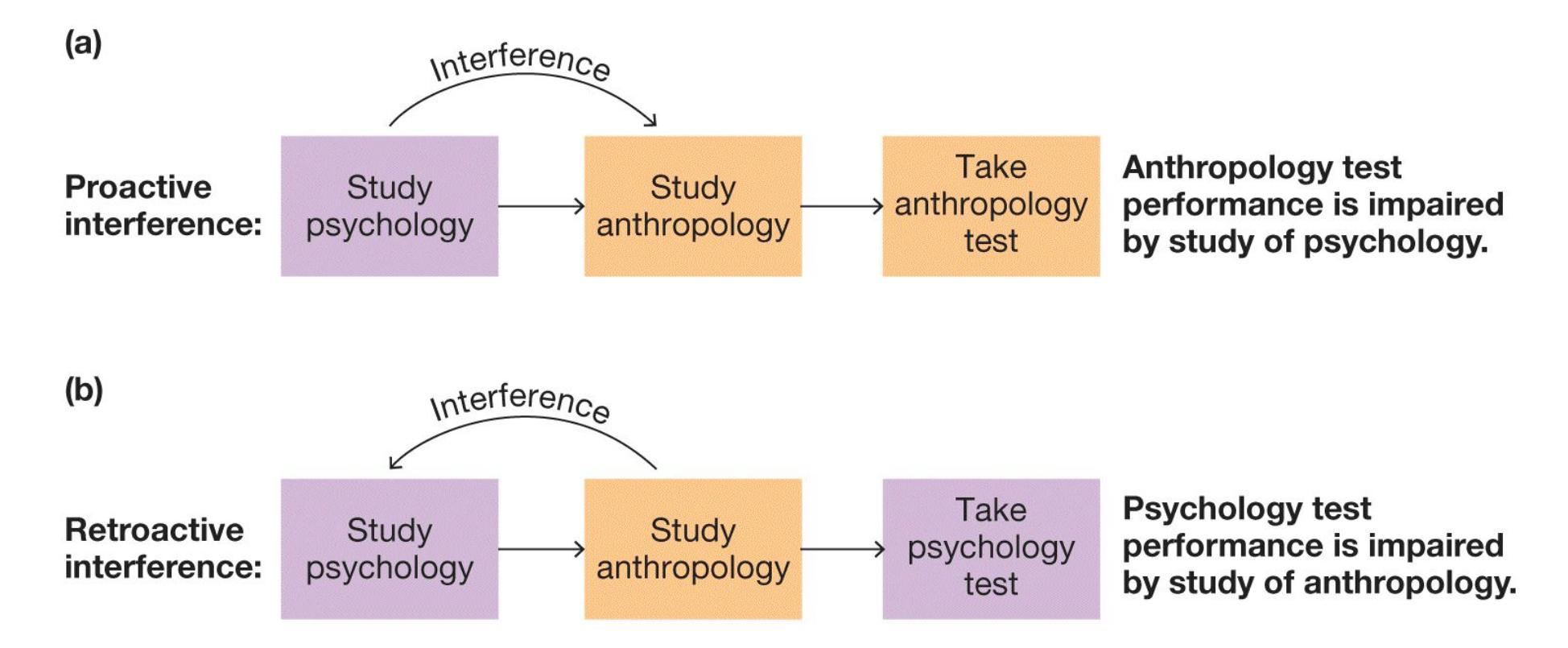

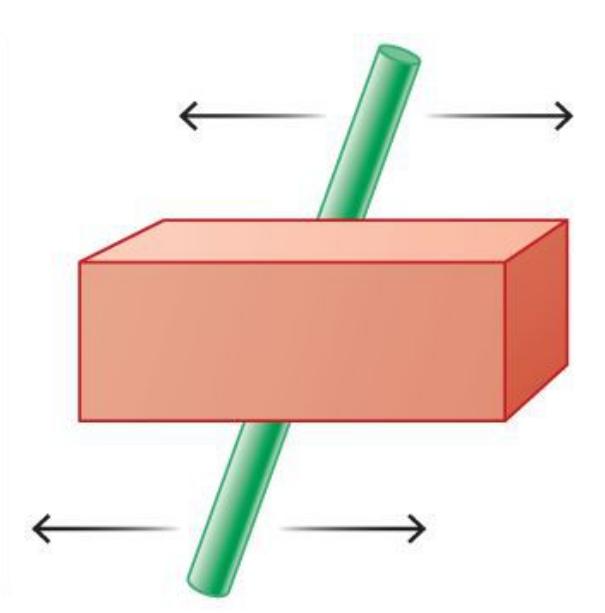

# FIGURE 1.2

# Critically Evaluating Research

Psychologists use critical thinking to evaluate provocative research questions. Here, Elliot Berkman cautions against believing the hype about brain training.

Being a critical thinker involves looking for holes in evidence, using logic and reasoning to see whether the information makes sense, and considering alternative explanations (**FIGURE 1.2**). It also requires considering whether the information might be biased, such as by personal or political agendas. Most people are quick to question information that does not fit with their beliefs. But as an educated person, you need to think critically about all information. Even when you "know" something, you need to keep refreshing that information in your mind. Ask yourself: Is my belief still true? What led me to believe it? What facts support it? Has science produced new findings that require me to reevaluate and update my beliefs? This exercise is important because you may be least motivated to think critically about information that verifies your preconceptions. In [Chapter 2](#page-83-0), you will learn much more about how critical thinking helps our scientific understanding of psychological phenomena. A feature throughout the book called "You Be the Psychologist" gives you opportunities to practice critical thinking about psychology.

# What is amiable skepticism?

**Answer:** being open to new ideas but carefully considering the evidence

## **Glossary**

# critical thinking

Systematically questioning and evaluating information using well-supported evidence.

# 1.3 Psychological Science Helps Us Understand Biased or Inaccurate Thinking

Psychologists have cataloged some ways that intuitive thinking can lead to errors (Gilovich, 1991; Hines, 2003; Kida, 2006; Stanovich, 2013). These errors and biases do not occur because we lack intelligence or motivation. Just the opposite is true. Most of these biases occur *because* we are motivated to use our intelligence. We want to make sense of events that involve us or happen around us. Our minds are constantly analyzing all the information we receive and trying to make sense of that information. These attempts generally result in relevant and correct conclusions.

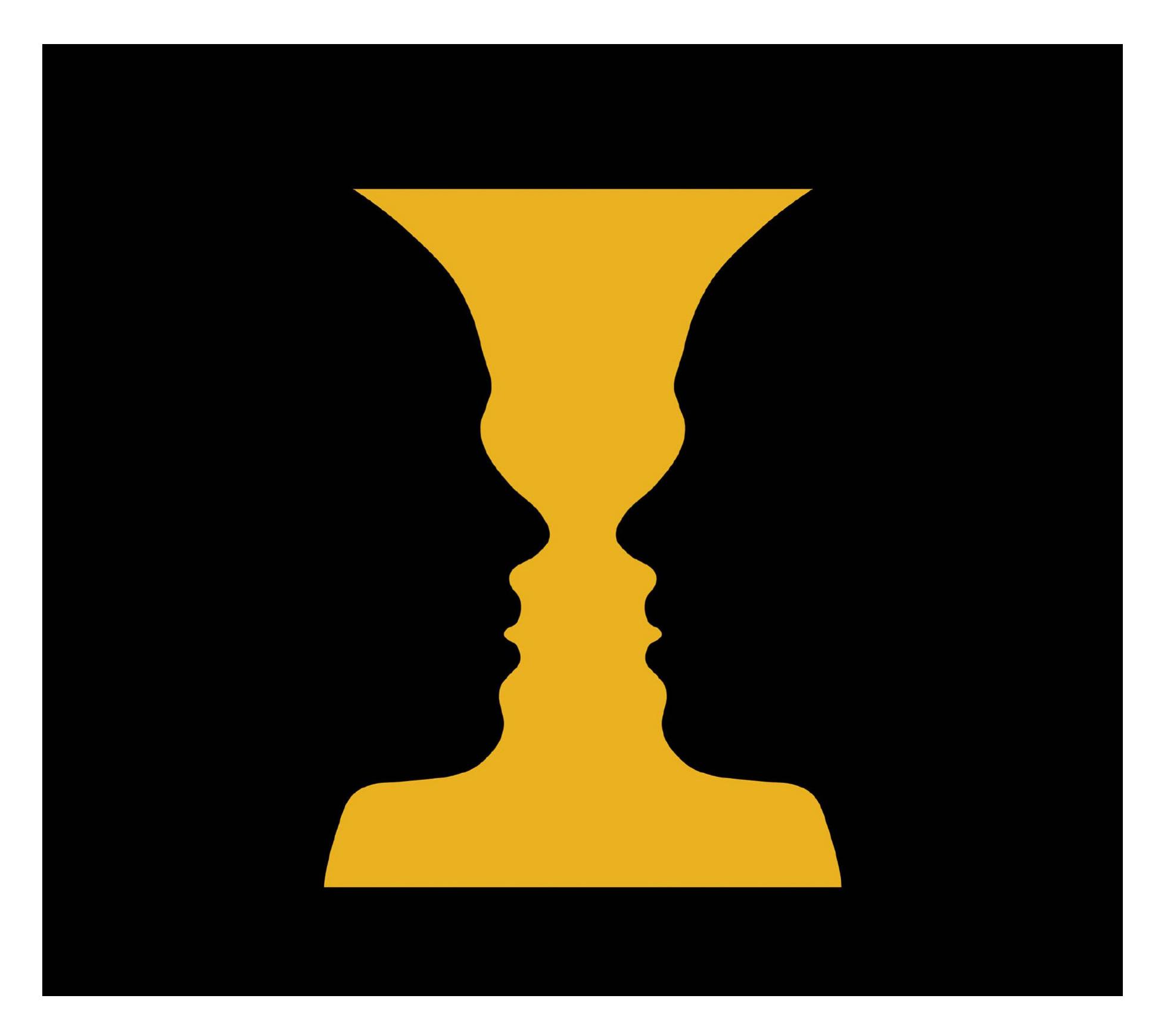

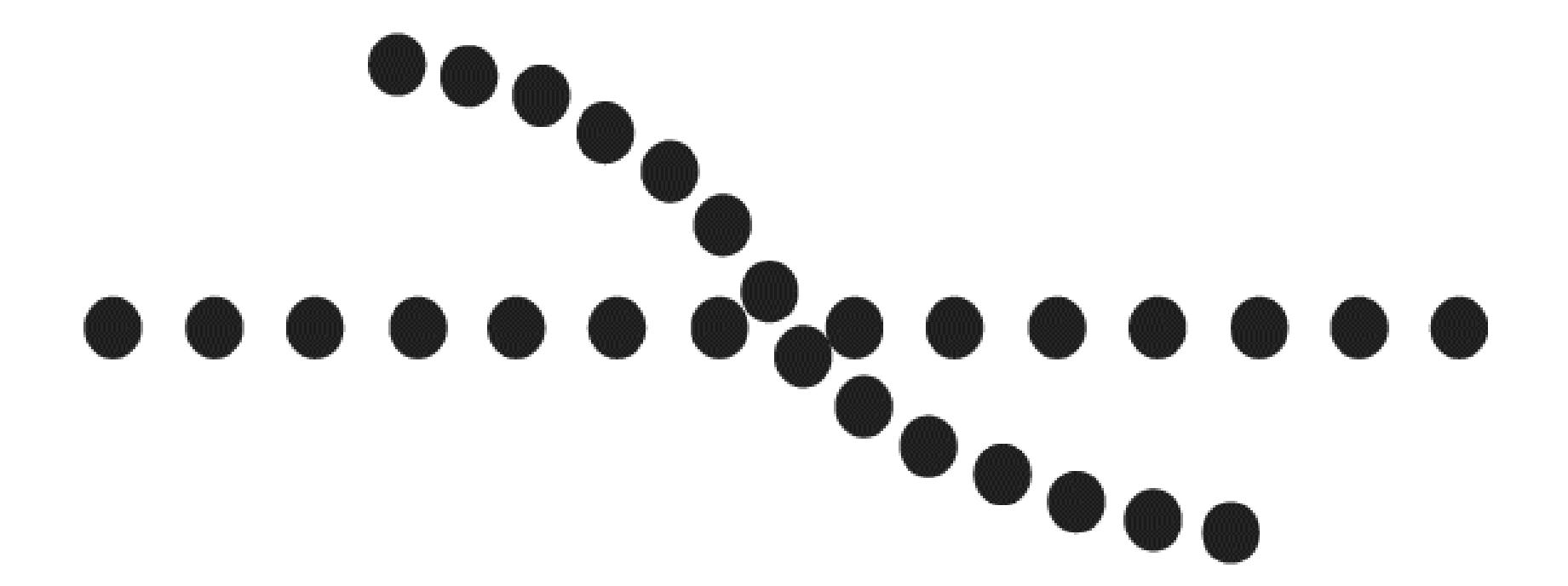

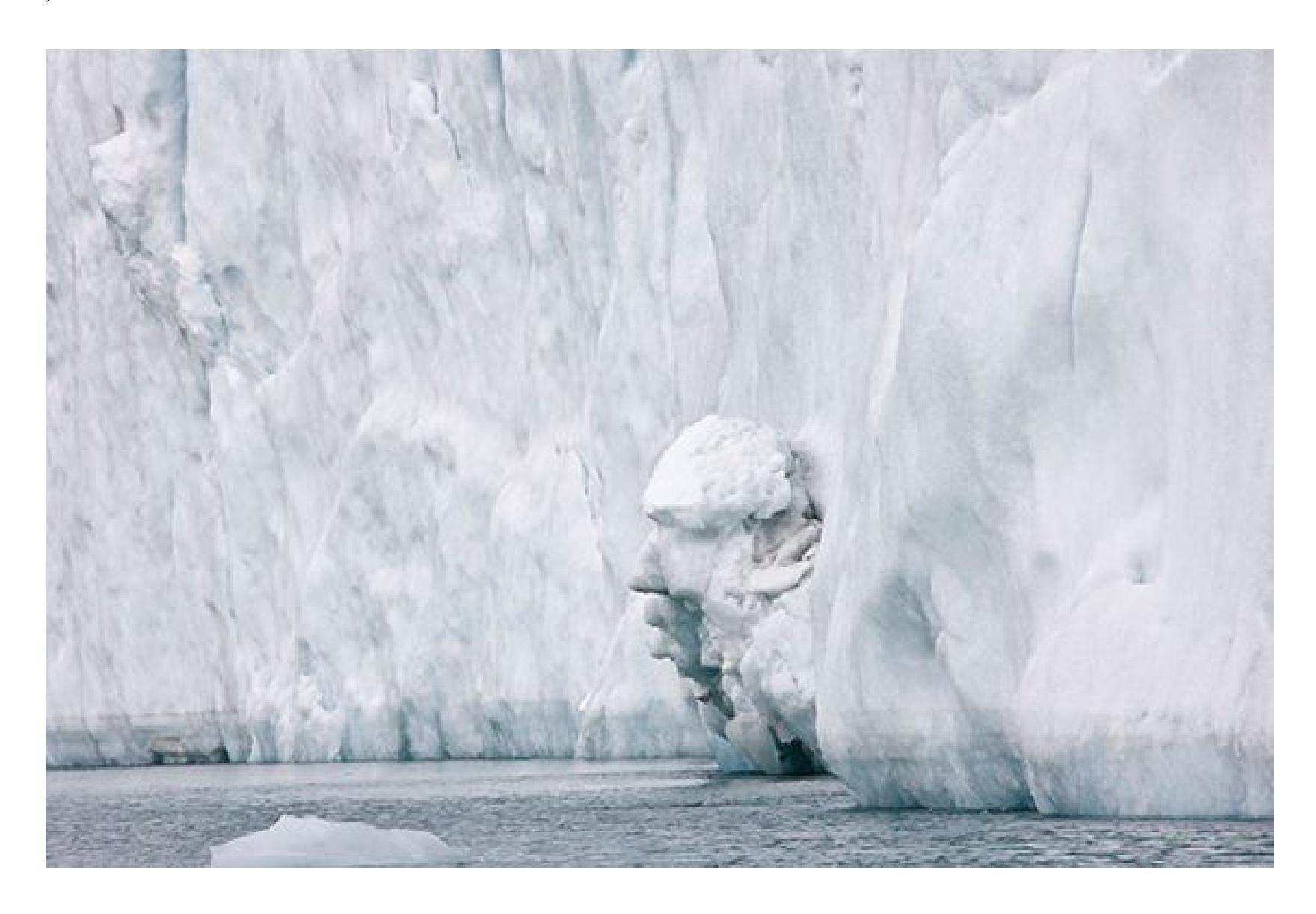

**FIGURE 1.3**

# Patterns That Do Not Exist

People often think they see faces in objects. When someone claimed to see the face of the Virgin Mary on this grilled cheese sandwich, the sandwich sold to a casino for \$28,000 on eBay.

Indeed, the human brain is highly efficient at finding patterns and noting connections between things. By using these abilities, we make new discoveries and advance society. But sometimes we see patterns that do not really exist (**FIGURE 1.3**). We see images of famous people in toast. We play recorded music backward and hear satanic messages. We believe that events, such as the deaths of celebrities, happen in threes. Often, we see what we expect to see and fail to notice things that do not fit with our expectations. For instance, as you will learn in [Chapter 12,](#page-1222-0) our stereotypes about people shape our expectations about them, and we interpret their behavior in ways that confirm these stereotypes.

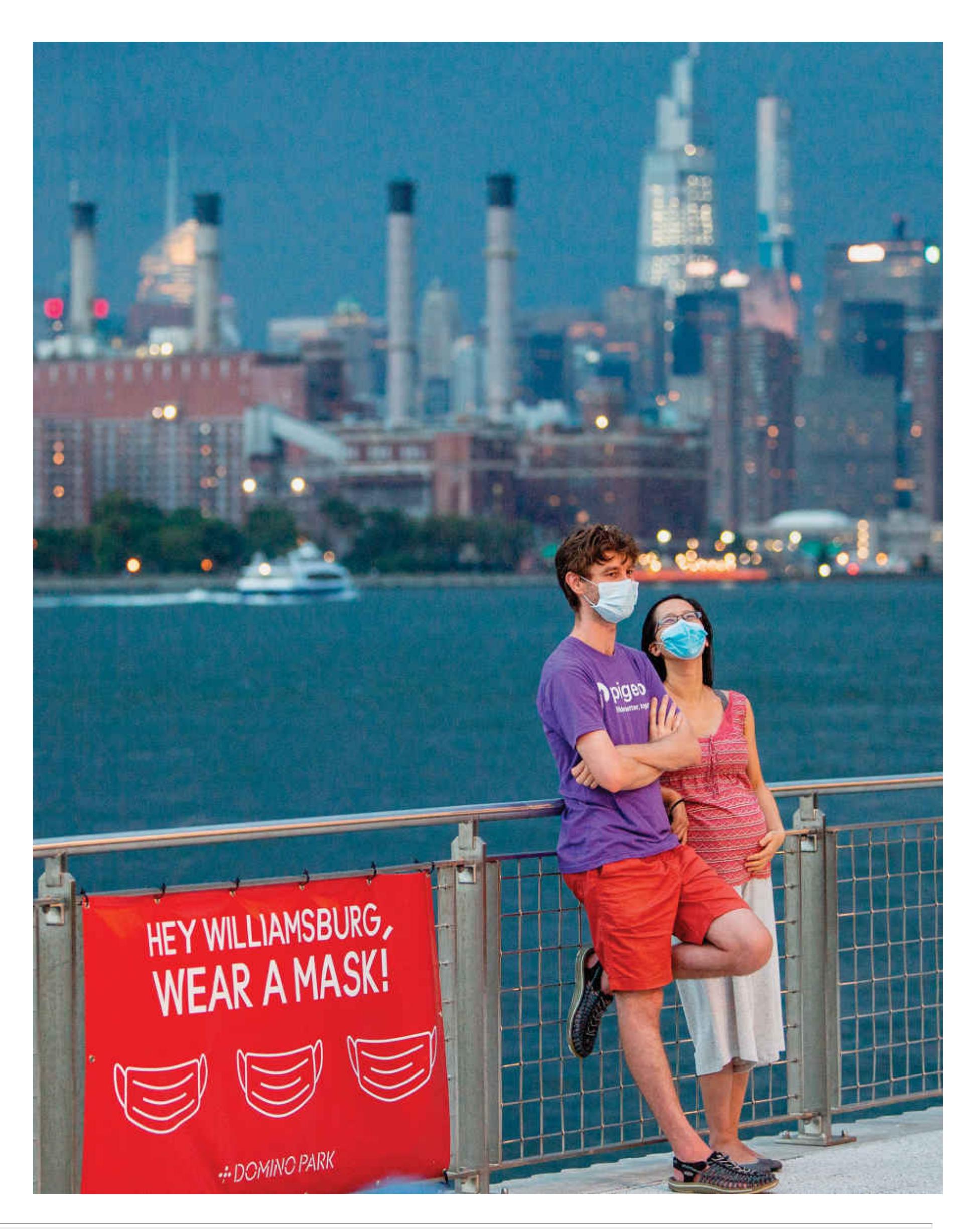

Why is it important to care about errors and biases in thinking? False beliefs can sometimes lead to dangerous actions. During the coronavirus pandemic that circled the globe in 2020, many people were motivated to believe that the disease was not as deadly as reported. Sometimes people reject information that is not consistent with their political beliefs or that threatens their self-image (for example, as being invulnerable to illness). People who dismissed the evidence about how the virus was spread were less likely to engage in social distancing and more likely to contract the disease (Hamel et al., 2020; Owens, 2020).

In each chapter, the feature "You Be the Psychologist" draws your attention to at least one major example of biased or erroneous thinking and how psychological science has provided insights into it. The following are a few of the common biases you will encounter.

- *Ignoring evidence (confirmation bias).* People are inclined to overweigh evidence that supports their beliefs and tend to downplay evidence that does not match what they believe. When people hear about a study that is consistent with their beliefs, they generally believe the study has merit. When they hear about a study that contradicts those beliefs, they look for flaws or other problems. One factor that contributes to confirmation bias is the selective sampling of information. For instance, people with certain political beliefs may visit only websites that are consistent with those beliefs. However, if we restrict ourselves to evidence that supports our views, then of course we will believe we are right. Similarly, people show selective memory, tending to better remember information that supports their existing beliefs.

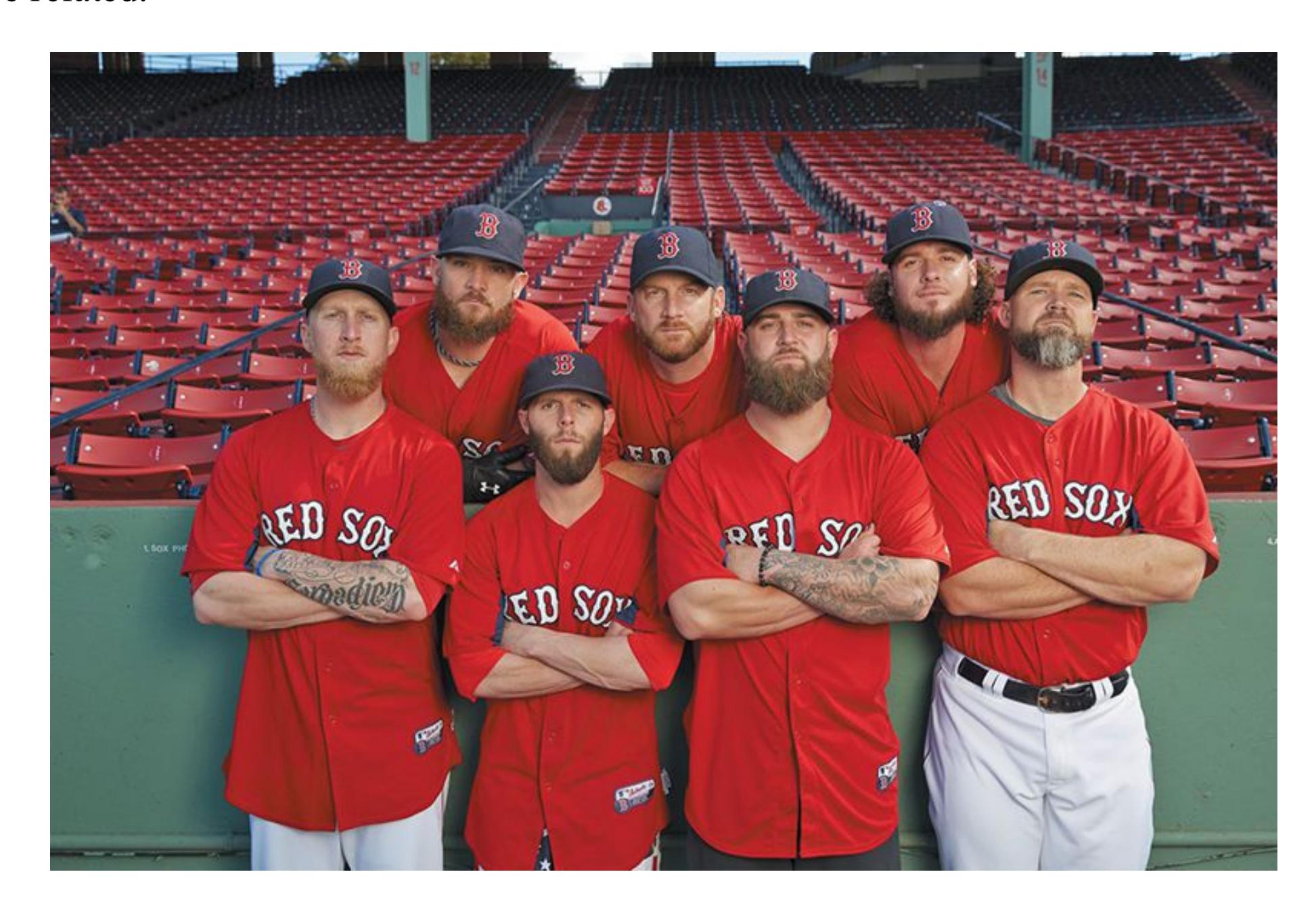

- *Seeing causal relationships that do not exist.* An extremely common reasoning error is the misperception that two events that happen at the same time must somehow be related. In our desire to find predictability in the world, we sometimes see order that does not exist. For instance, over the past 200 years, the mean global temperature has increased, and during that same period the number of pirates on the high seas has decreased. Would you argue that the demise of pirates has led to increased global warming?

*Accepting after-the-fact explanations.* Another reasoning bias is known as *hindsight bias*. We are wonderful at explaining why things happened in the past, but we are much less successful at predicting future events. Think about the shooting in 2016 at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. In hindsight, we know that there were warning signs that the shooter might become violent, such as a history of violence against women (**FIGURE 1.4**). Yet none of these warning signs prompted anyone to take action. People saw the signs but failed to predict the tragic outcome. More generally, once we know the outcome, we interpret and reinterpret old evidence to make sense of that outcome. We need to be wary of after-the-fact explanations because they give a false sense of certainty about our ability to make predictions about future behavior.

**FIGURE 1.4**

# Orlando Pulse Shootings

In hindsight, there were warning signs that the shooter, Omar Mateen, was troubled. But it is very difficult to predict violent behavior in advance.

*Taking mental shortcuts.* People often follow simple rules, called *heuristics*, to make decisions. These mental shortcuts are valuable because they often produce reasonably good decisions without too much effort (Kahneman, 2011). But at times heuristics can lead to inaccurate judgments and biased outcomes. One example of this problem occurs when things that come most easily to mind guide our thinking. This shortcut is known as the *availability heuristic*. For example, child abductions are much more likely to be reported in the news than more common dangers are, and the vivid nature of the reports makes them easy to remember. After hearing a series of news reports about child abductions, parents may overestimate their frequency and become overly concerned that their children might be abducted. As a result, they may underestimate other dangers facing their children, such as bicycle accidents, food poisoning, or drowning. Similar processes lead people to drive rather than fly even though the chances of injury or death from passenger vehicles are much greater than the chances of dying in a plane crash. In [Chapter 8,](#page-772-0) we will consider a number of heuristic biases.

# Why should you be suspicious of after-the-fact explanations?

**Answer:** Once people know an outcome, they interpret and reinterpret old evidence to make sense of that outcome, giving a false sense of predictability.

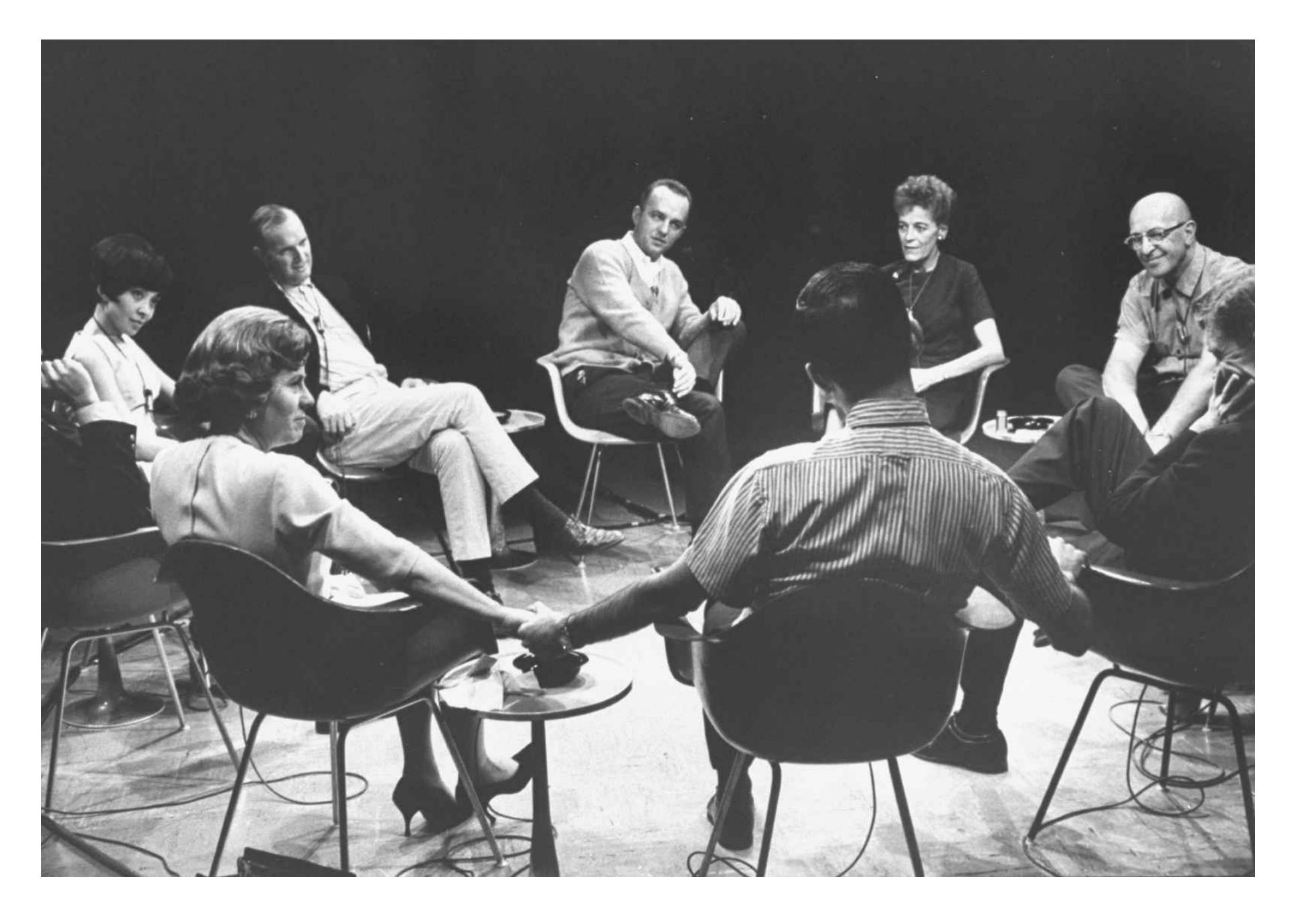

**YOU BE THE PSYCHOLOGIST**

# 1.4 Why Are People Unaware of Their Weaknesses?

Another bias in thinking is that people are motivated to feel good about themselves, and this motivation affects how they interpret information (Cai et al., 2016). For example, many people believe they are better than average on any number of dimensions. Ask your friends, for example, if they think they are better-thanaverage drivers. More than 90 percent of drivers hold this belief despite the statistical reality that only 50 percent can be above average. People use various strategies to support their positive views, such as choosing a definition of what it means to be good at something in a self-serving way. The flip side of this is that people are resistant to recognizing their own weaknesses. Consider the following.

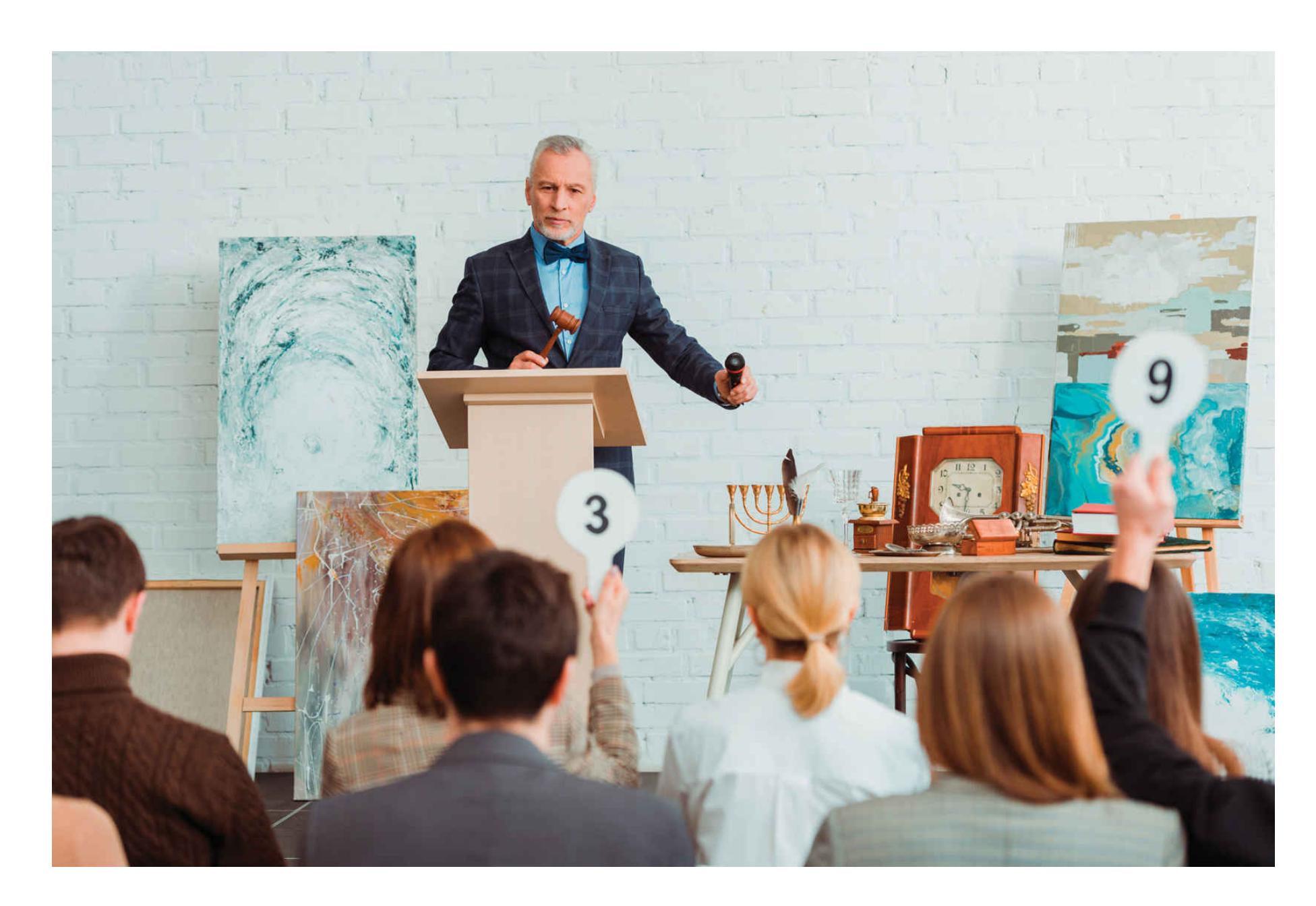

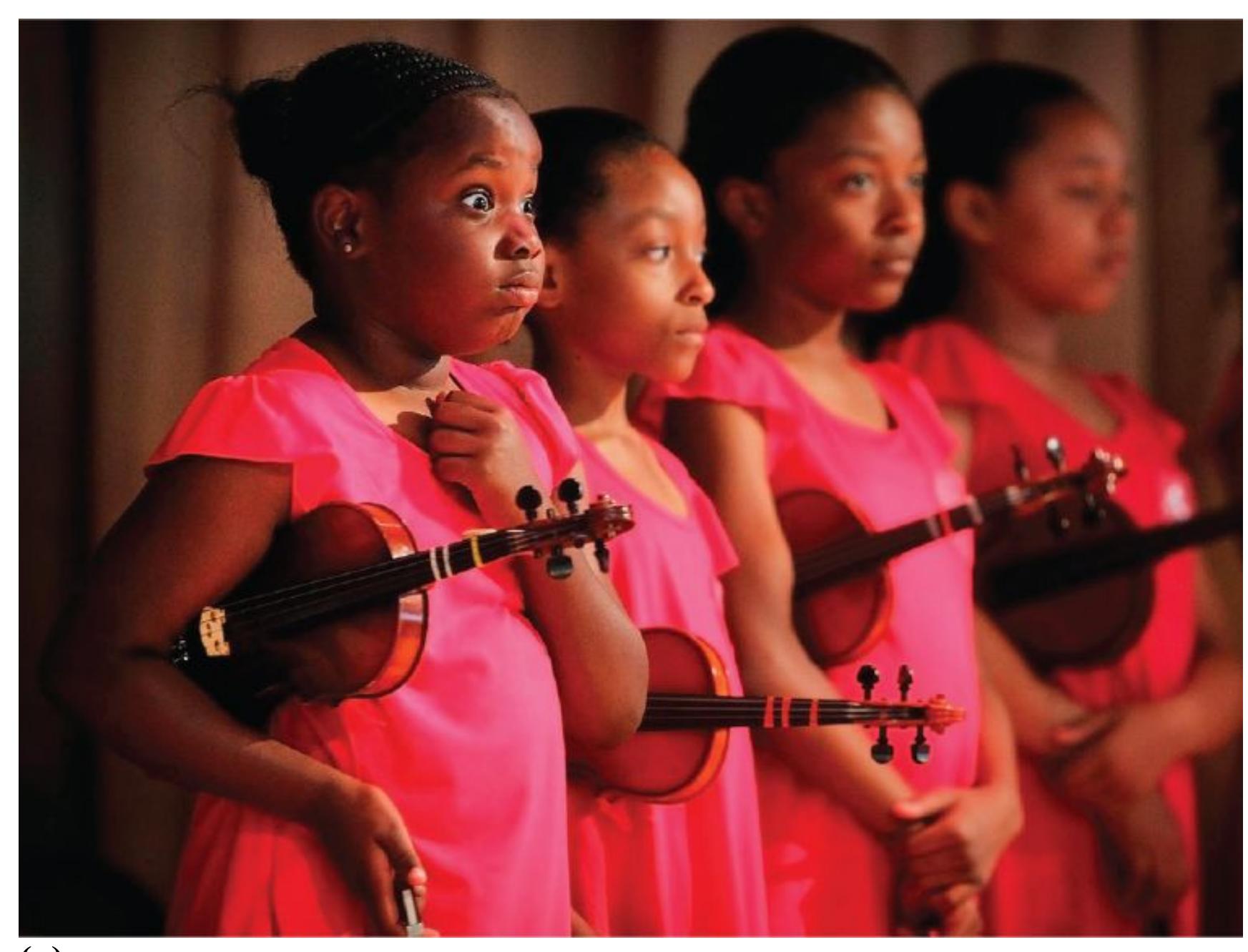

You are judging an audition for a musical, and the singer, while passionate, is just awful (**FIGURE 1.5**). Everyone in the room is laughing or holding back laughter out of politeness. When the judges react unenthusiastically and worse, the performer is crushed and cannot believe the verdict. "But everyone says I am a great singer," he argues. "Singing is my life!" You sit there thinking, *How does he not know how bad he is?*

**FIGURE 1.5**

# Judging a Performance

Judges react to an audition.

How is it that people who are tone-deaf can believe their singing talents merit participating in singing competitions? The social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger have an explanation: People are often blissfully unaware of their weaknesses because they cannot judge those weaknesses at all (Dunning et al., 2003; Kruger & Dunning, 1999). How does this limitation come about?

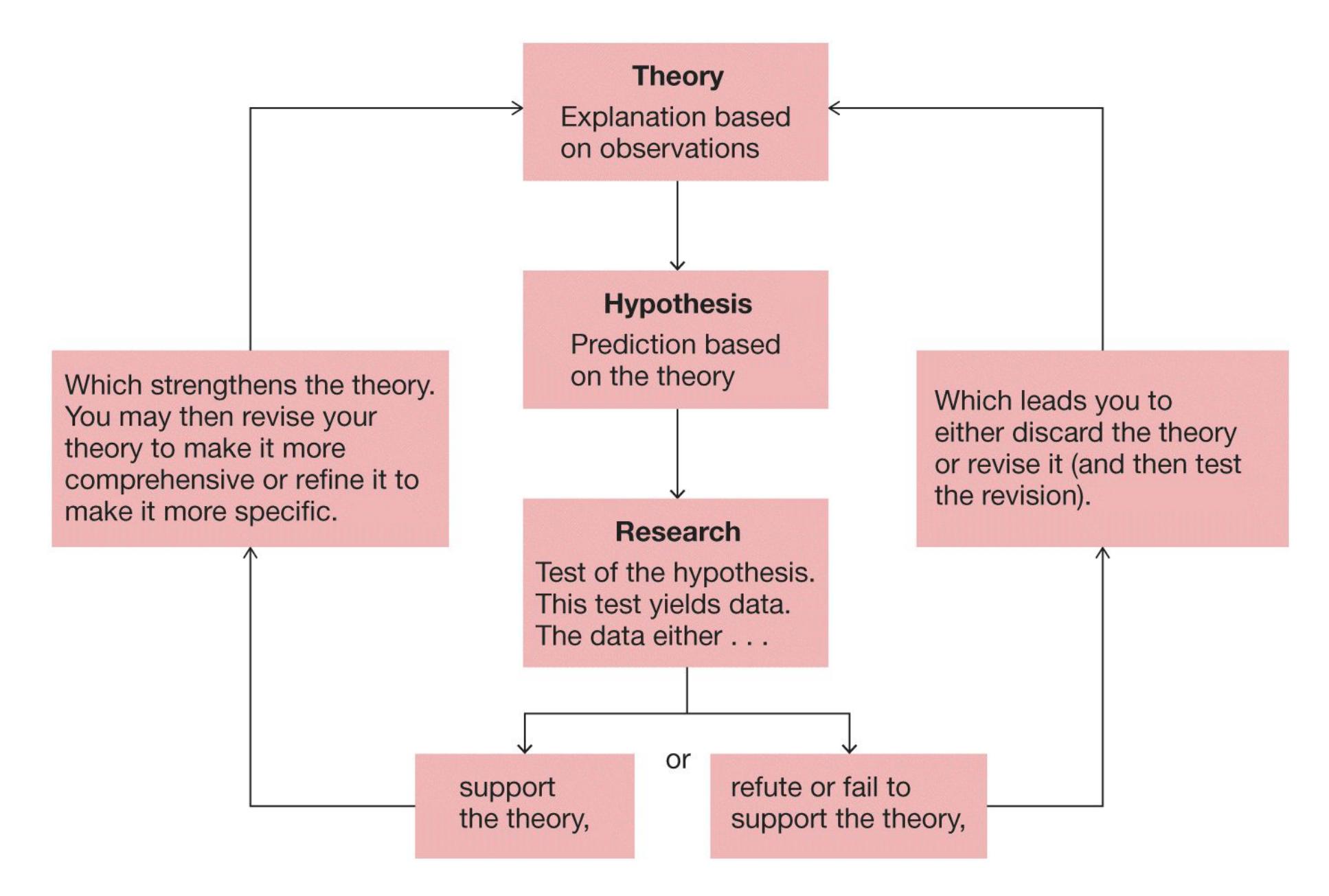

Take a moment to consider some possibilities. This kind of thinking is known as *hypothesis generation*, and it occurs near the beginning of the scientific process. Hypothesis generation is also one of the most fun parts of thinking like a psychologist. You get to explore the idea space of explanations. Are people unaware of their weaknesses because they have never bothered to think carefully about them? Or is it that they have never received honest feedback? Try to come up with three explanations for the effect. And keep in mind that there is rarely only one

explanation for something in psychology, so combinations of explanations count, too!

**FIGURE 1.6**

# Personal Ratings Versus Actual Performance

Students rated their mastery of course material and test performance. Points on the *y*-axis reflect how the students perceived their percentile rankings (value on a scale of 100). Points on the *x*-axis reflect these students' actual performance rank (*quartile* here means that people are divided into four groups). The top students' predictions were close to their actual results. By contrast, the bottom students' predictions were far off.

In studies of college students, Dunning and Kruger found that people with the lowest grades rate their mastery of academic skills much higher than is warranted by their performance (**FIGURE 1.6**). A student who receives a grade of C may protest to the instructor, "My work is as good as my roommate's, but she got an A." This result hints that one explanation might be that people lack the ability to evaluate their own performance in areas where they have little expertise—a phenomenon known as the *Dunning-Kruger ef ect*.

Of course, additional explanations might also be at play. Think like a psychologist and ask yourself: Why do people hold overly rosy estimations of their own abilities to begin with? How does it benefit us, and when might it be harmful? What function does it serve for us in social situations? In [Chapter 12,](#page-1222-0) you will learn why most people believe they are better than average in many things. As is often the case in psychology research, the answer to one question leads us to the next. Thinking like a psychologist begins, and ends, by asking questions and considering multiple possible answers. ■

**Why should you be skeptical of people's descriptions of their personal strengths?**

**Answer:** because people often lack the expertise to accurately evaluate and compare their abilities.

# What Is the Scientific Scope of Psychology?

# Learning Objectives

- Trace the history of the mind/body problem and the nature/nurture debate.

- Define the concept of functionalism and understand how it fits into an evolutionary framework.

- Identify the major areas of research within psychology and the focus of their work.

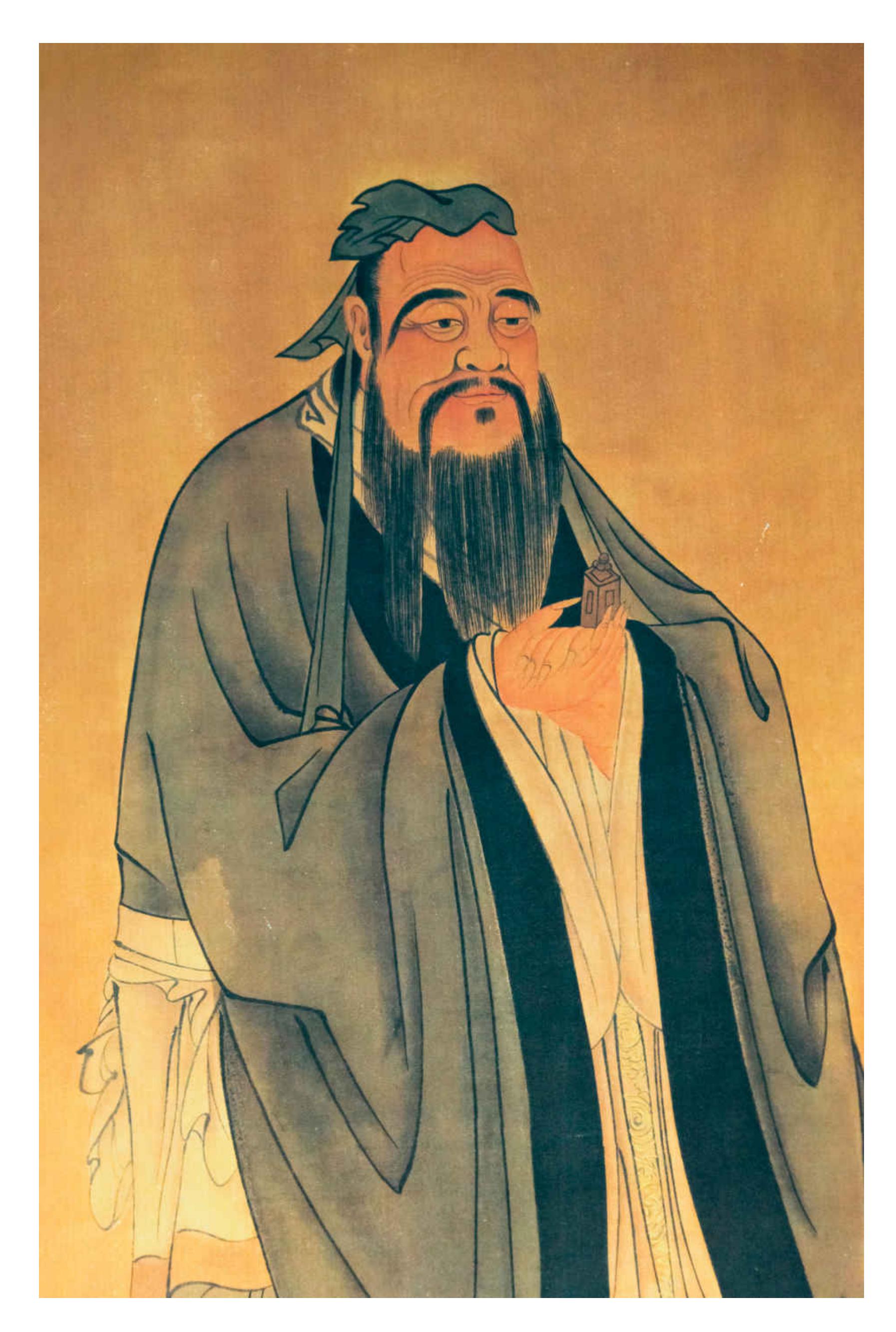

**FIGURE 1.7**

# Confucius

Confucius studied topics that remain important in contemporary psychology.

Psychology originated with the ancient philosophers, who explored questions about human nature. For example, the Chinese philosopher Confucius emphasized human development, education, and interpersonal relations, all of which remain contemporary topics in psychology around the world (Higgins & Zheng, 2002; **FIGURE 1.7**). But it was not until the 1800s that psychologists began to use scientific methods to investigate mind, brain, and behavior. Now, psychologists study a wide range of topics, from brain and other biological mechanisms to life span development to cultural and social issues.

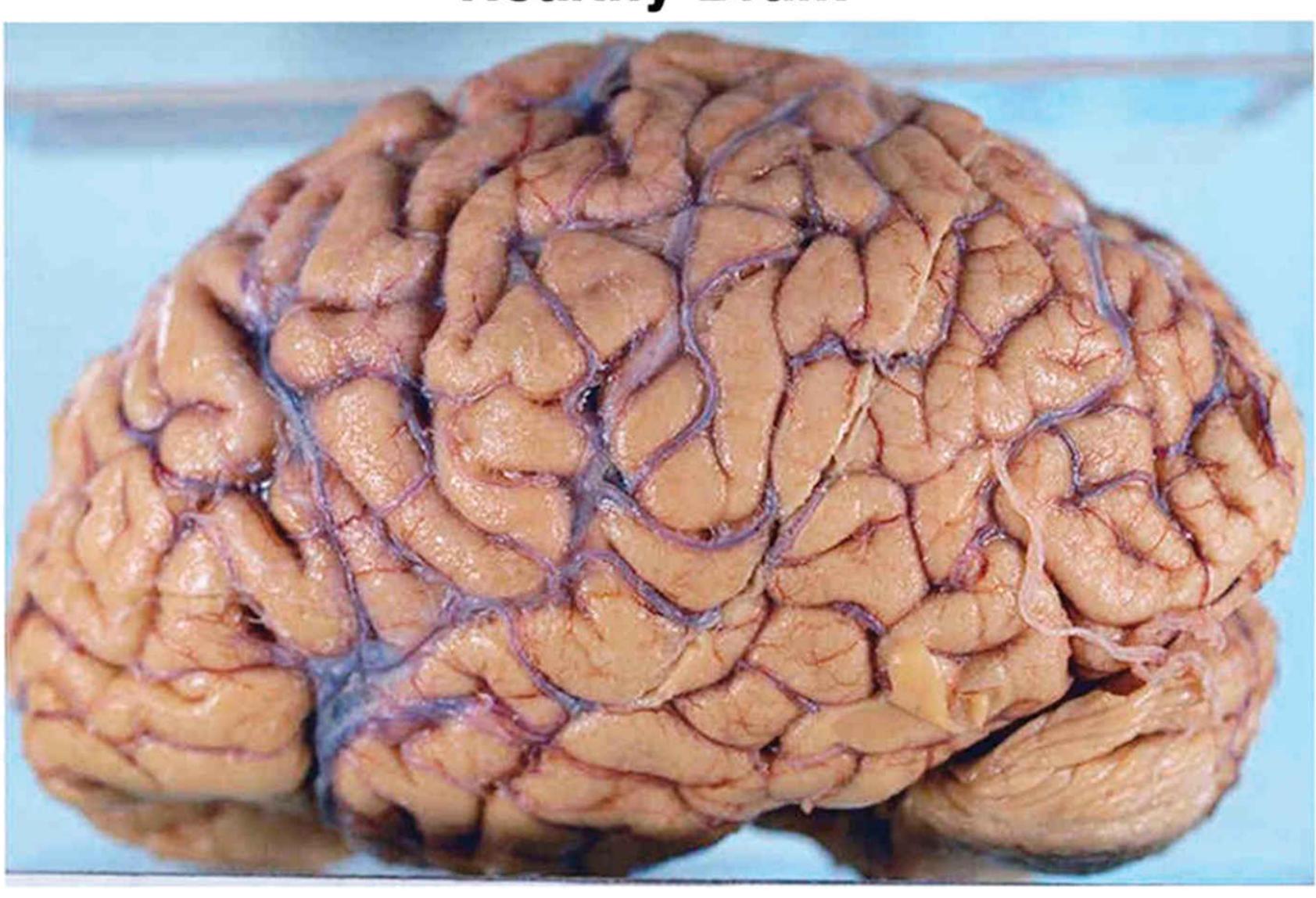

# 1.5 Many Psychological Questions Have a Long History

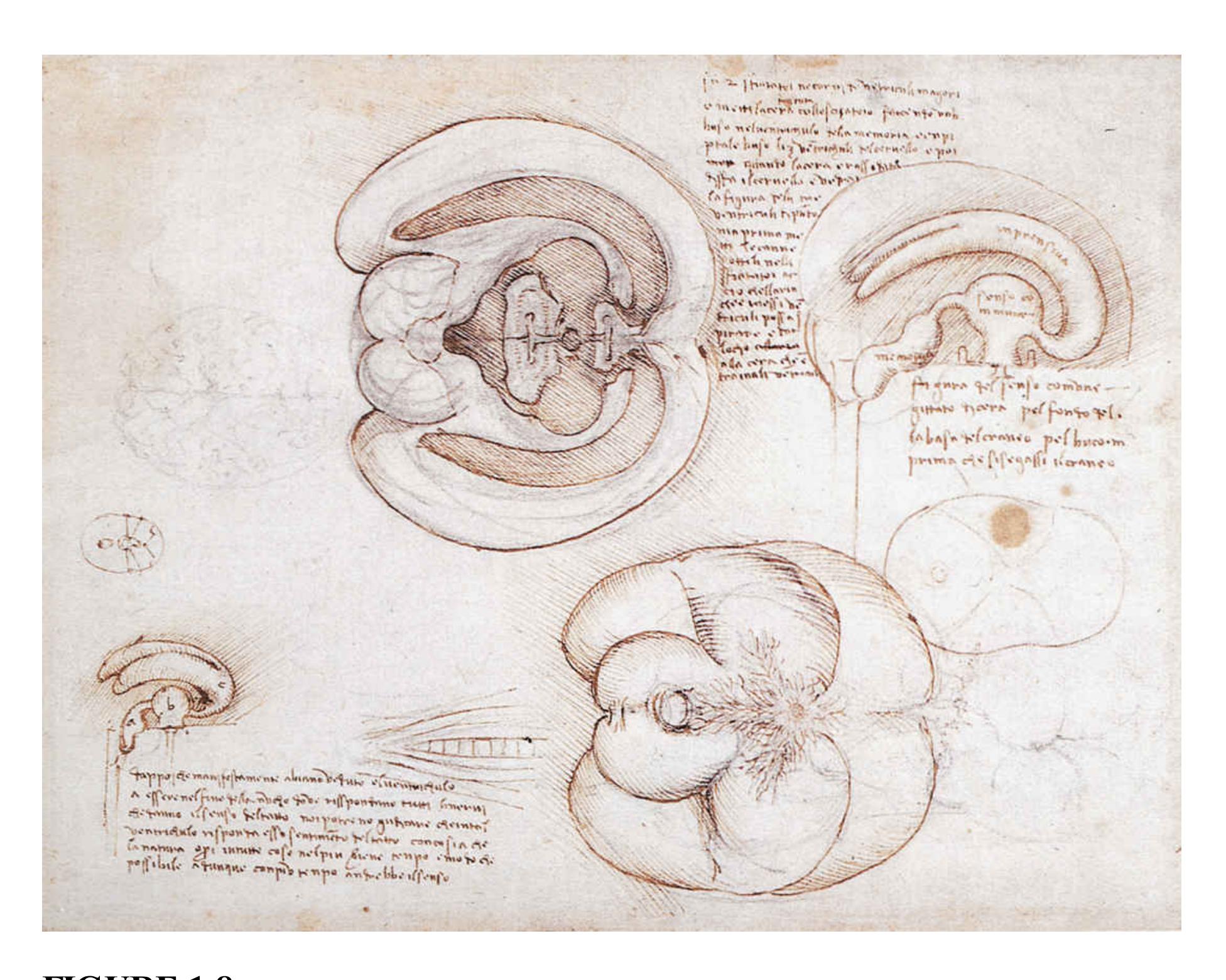

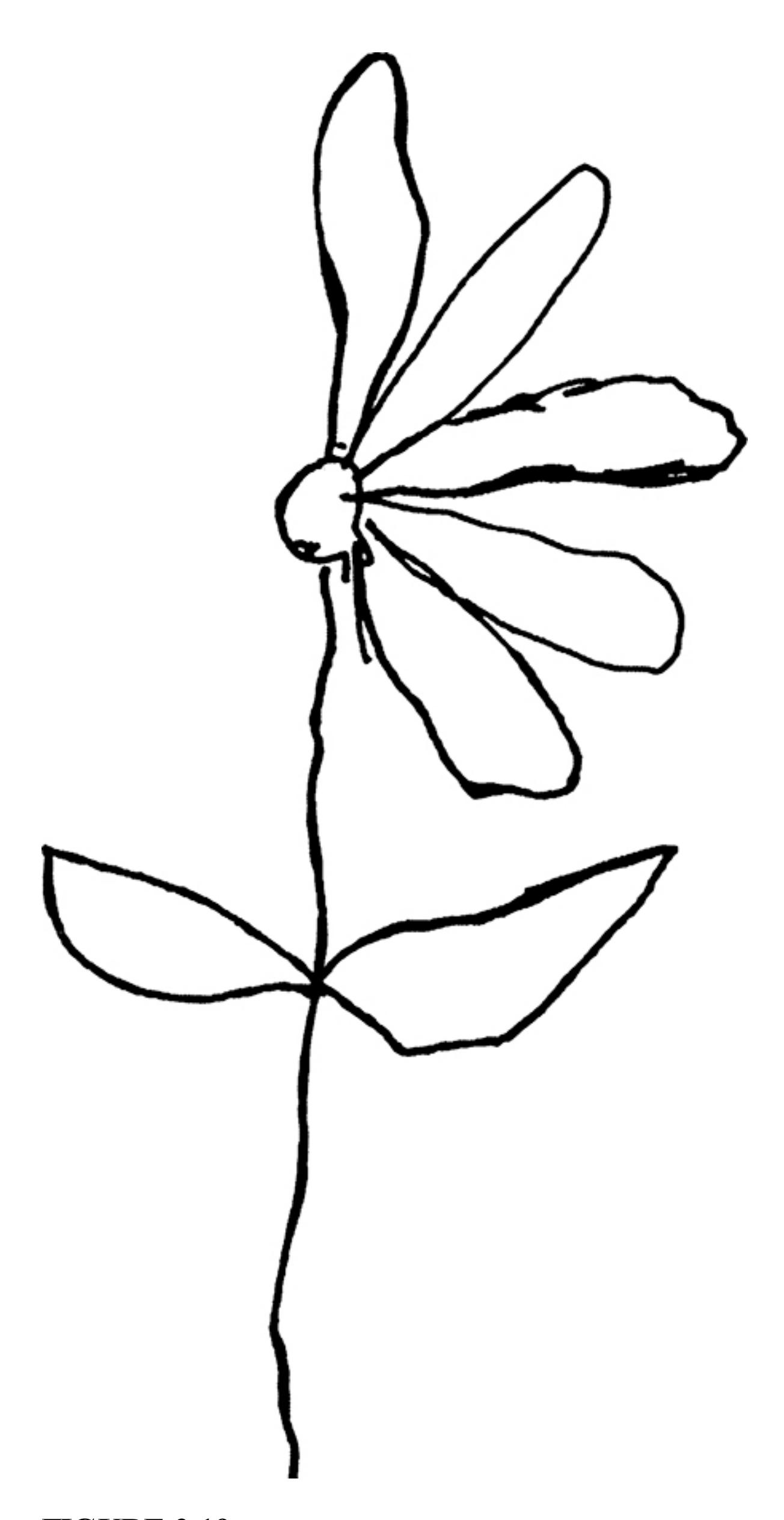

Since at least the times of ancient Greece, people have wondered why humans think and act in certain ways. The [mind/body problem](#page-26-0) was perhaps the quintessential psychological issue: Are the mind and body separate and distinct, or is the mind simply the subjective experience of ongoing brain activity? Throughout history, the mind has been viewed as residing in many organs of the body, including the liver and the heart. The ancient Egyptians, for example, elaborately embalmed each dead person's heart, which was to be weighed in the afterlife to determine the person's fate. They simply threw away the brain. In the following centuries, scholars continued to believe that the mind was separate from the body, as though thoughts and behaviors were directed by something other than the squishy ball of tissue between our ears. Around 1500, the artist Leonardo da Vinci challenged this doctrine when he dissected human bodies to make his anatomical drawings more accurate. His dissections led him to many conclusions about the brain's workings. Some of da Vinci's specific conclusions about brain functions were not accurate, but his work represents an early and important attempt to link the brain's anatomy to psychological functions (**FIGURE 1.8**).

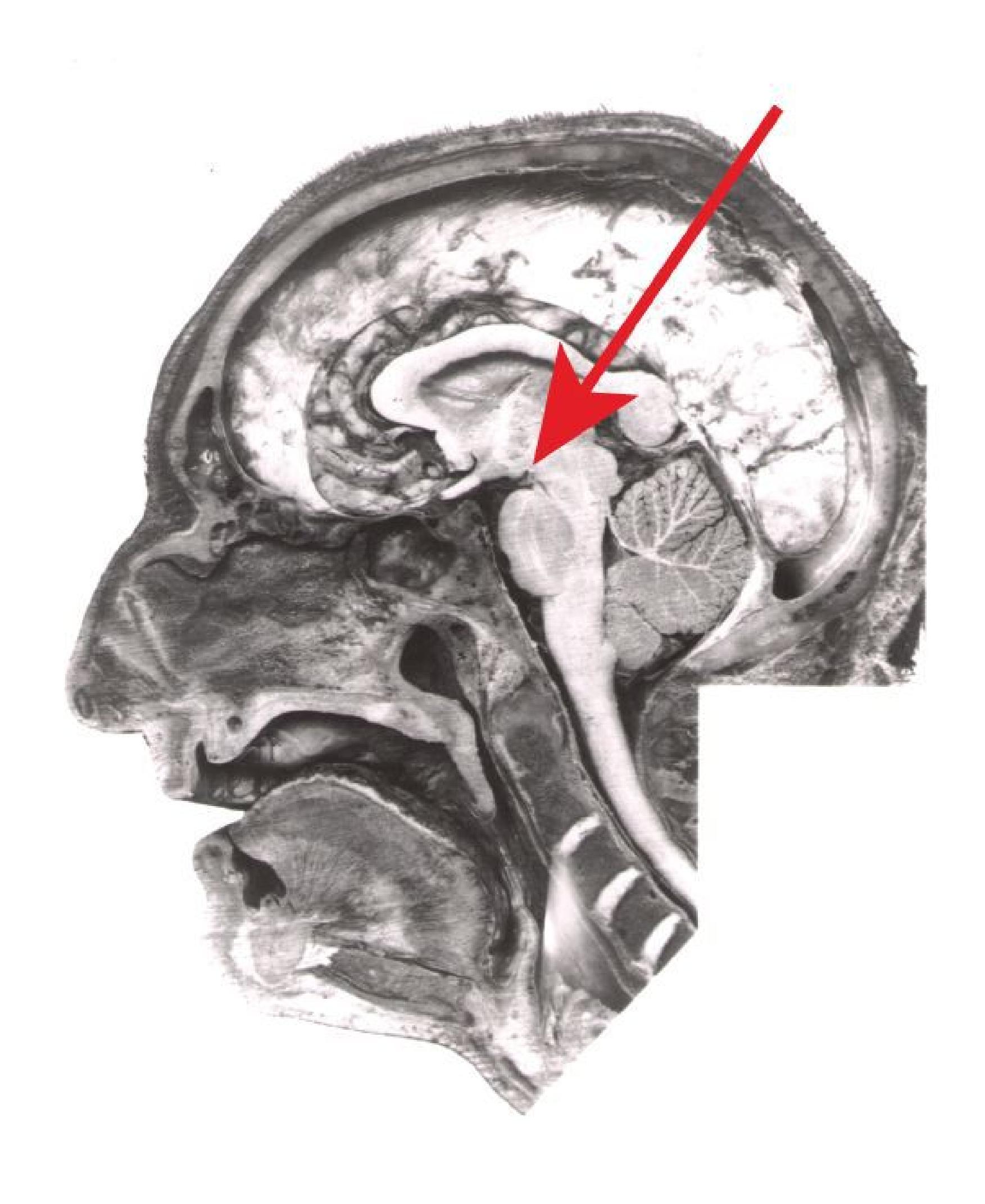

# FIGURE 1.8

# Da Vinci and the Brain

This drawing by Leonardo da Vinci dates from around 1506. Da Vinci used a wax cast to study the brain. He believed that sensory images arrived in the middle region of the brain. He called this region the *sensus communis*.

In the 1600s, the philosopher René Descartes promoted the influential theory of *dualism*. This term refers to the idea that the mind and the body are separate yet intertwined. In earlier views of dualism, mental functions had been considered the mind's sovereign domain, separate from body functions. Descartes proposed a somewhat different view. The body, he argued, was nothing more than an organic machine governed by "reflex." Many mental functions—such as memory and imagination—resulted from body functions. Deliberate action, however, was controlled by the rational mind. And in keeping with the prevailing religious beliefs, Descartes concluded that the rational mind was divine and separate from

the body. Nowadays, psychologists reject dualism. In their view, the mind arises from brain activity, and the activities of the mind change the brain. The mind and brain do not exist separately.

# Learning Tip

**Students often confuse the mind/body problem and the nature/nurture debate. This is understandable because they are similar in some ways. Remember, however, that the mind/body problem speaks to the** *separation of mental life and the body***. For instance, is an emotion separate from the brain that produces it? In contrast, the nature/nurture debate is about the** *origin of mental life***. Is an emotion caused by genetics or culture (regardless of whether the emotion "lives" in the mind or brain)?**

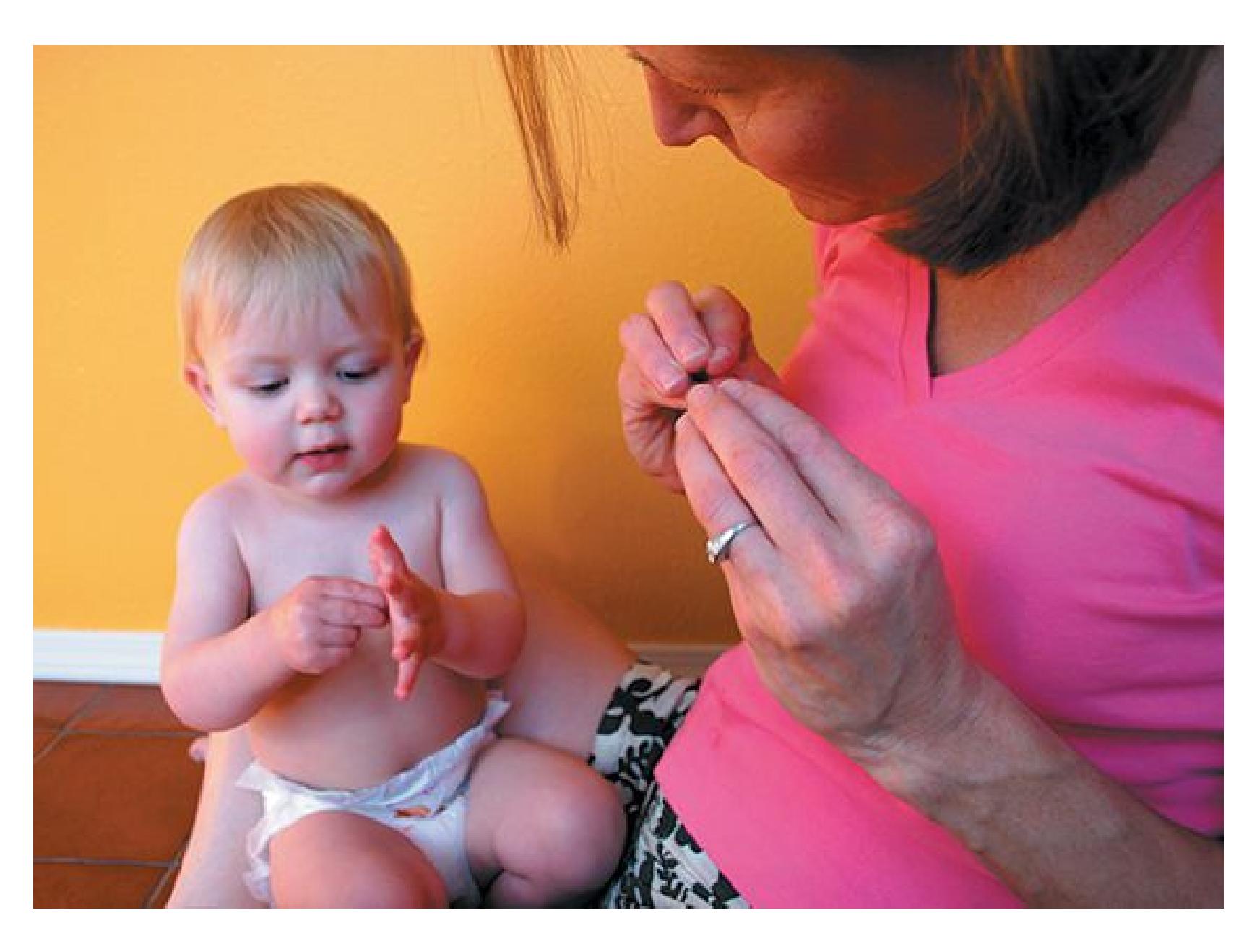

Other questions considered by the ancients are still explored by psychologists today. Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato debated whether an individual's psychology is attributable more to *nature* or to *nurture*. That is, are psychological characteristics biologically innate? Or are they acquired through education, experience, and [culture—](#page-26-1)the beliefs, values, rules, norms, and customs existing within a group of people who share a common language and environment? The [nature/nurture debate](#page-26-2) has taken one form or another throughout psychology's history. Psychologists now widely recognize that nature and nurture dynamically interact in human psychological development. For example, consider a college basketball player who is very tall (nature) and has an excellent coach (nurture). That player has a better chance of excelling enough to become a professional player than does an equally talented player who has only the height or the coach. In many of the psychological phenomena you will read about in this book, nature and nurture are so enmeshed that they cannot be separated.

**Why is it important for psychologists to pay attention to both nature and nurture?**

**Answer:** They both contribute to our mental activity and behavior, individually and in interaction with each other.

## **Glossary**

# mind/body problem

A fundamental psychological issue: Are mind and body separate and distinct, or is the mind simply the physical brain's subjective experience?

# culture

The beliefs, values, rules, norms, and customs that exist within a group of people who share a common language and environment.

# nature/nurture debate

The arguments concerning whether psychological characteristics are biologically innate or acquired through education, experience, and culture.

# 1.6 Mental Processes and Behaviors Serve Functions for Individuals and Groups

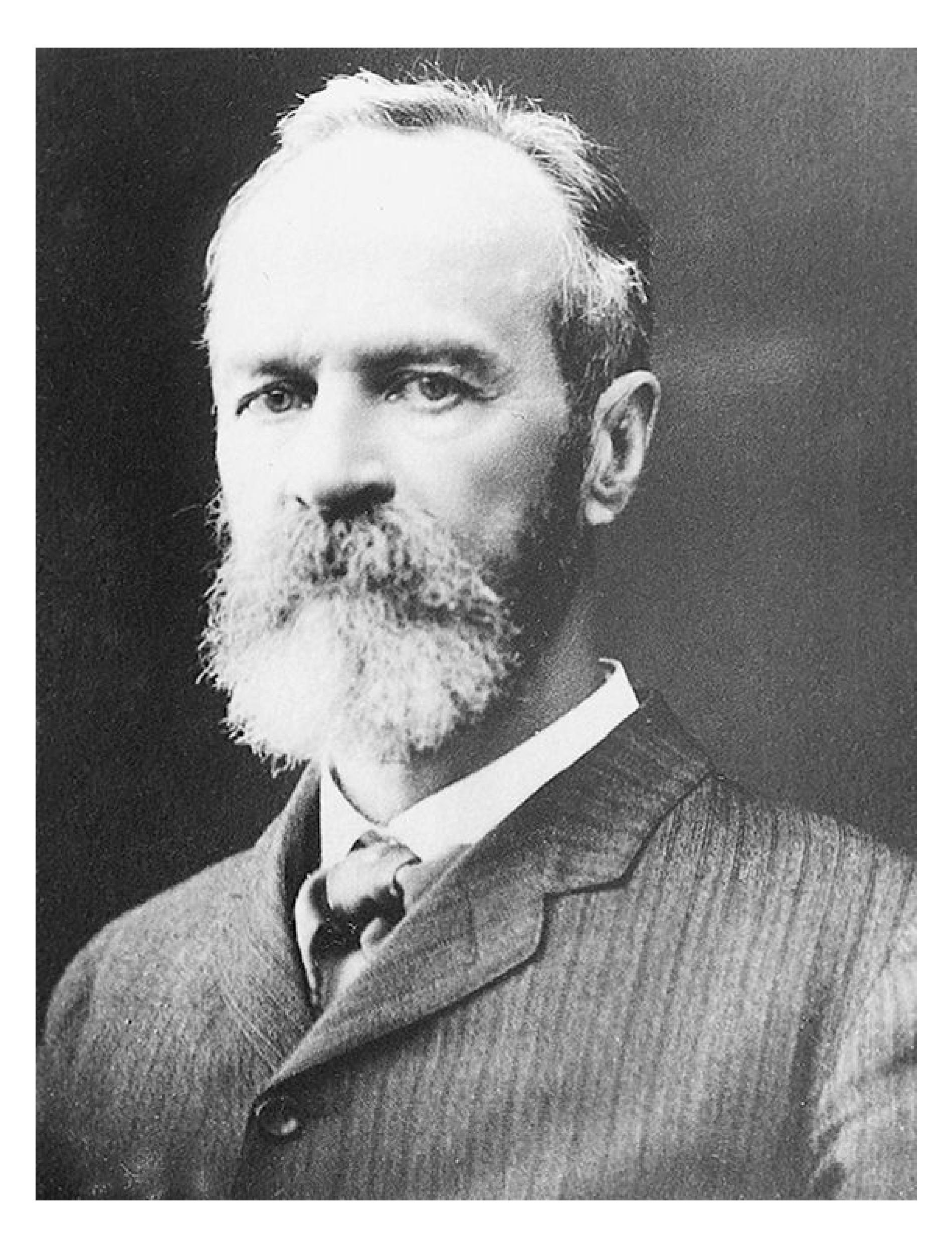

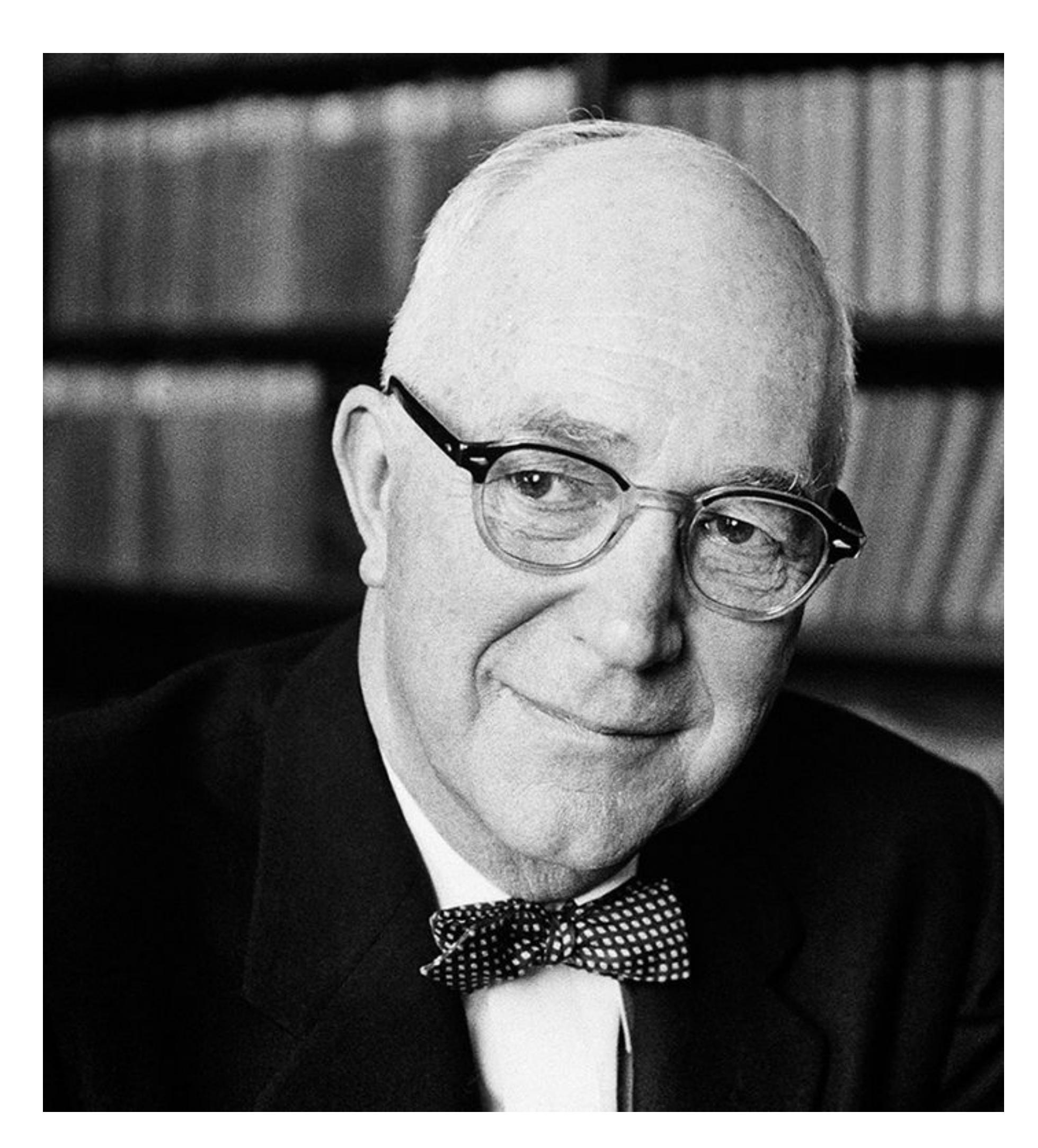

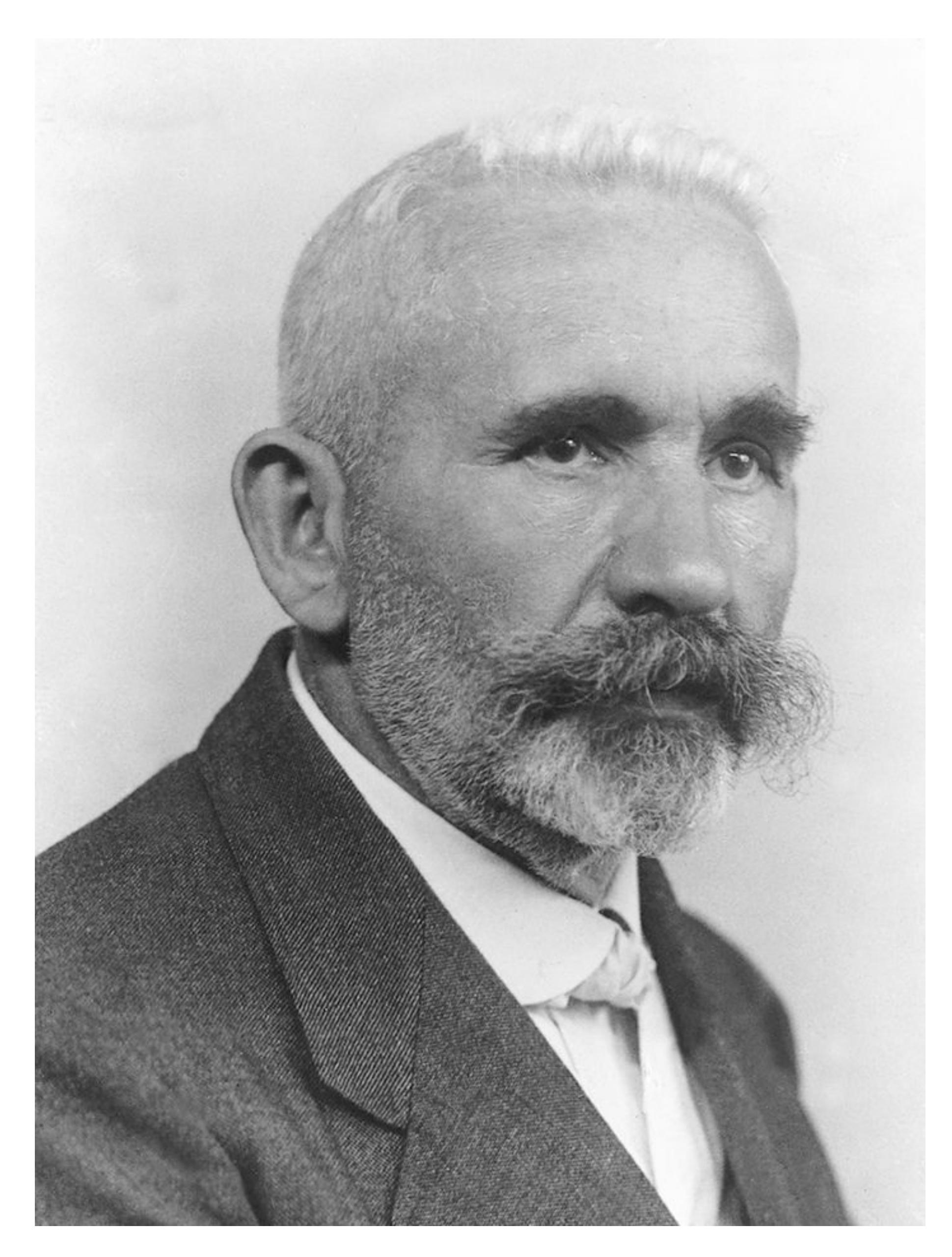

**FIGURE 1.9 William James**

In 1890, James published the first major overview of psychology. Many of his ideas have passed the test of time. In theorizing about how the mind works, he moved psychology beyond considering minds as sums of individual units (e.g., a sensory part, an emotional part, and so forth) and into functionalism.

In the mid-1800s in Europe, psychology arose as a field of study built on the experimental method. In *A System of Logic* (1843), the philosopher John Stuart Mill declared that psychology should leave the realms of philosophy and speculation and become a science of observation and experiment. Indeed, he defined psychology as "the science of the elementary laws of the mind" and argued that only through the methods of science would the processes of the mind be understood. Throughout the 1800s, early psychologists increasingly studied mental activity through careful scientific observation.

If one person could be credited for laying the intellectual foundation for modern psychology, it would be William James, a brilliant scholar whose wide-ranging work has had an enormous, enduring impact on psychology (**FIGURE 1.9**). In 1873, James abandoned a career in medicine to teach physiology at Harvard University. In 1875, he gave his first lecture on psychology. (He later quipped that it was also the first lecture on psychology he had ever heard.) He was among the first professors at Harvard to openly welcome questions from students rather than have them listen silently to lectures. James also was an early supporter of women trying to break into the male-dominated sciences. He trained Mary Whiton Calkins, who was the first woman to set up a psychological laboratory and was the first woman president of the American Psychological Association (**FIGURE 1.10**).

# FIGURE 1.10

# Mary Whiton Calkins

Calkins was an important early contributor to psychological science. In 1905, she became the first woman president of the American Psychological Association.

James's personal interests were more philosophical than physiological. He was captivated by the nature of conscious experience. To this day, psychologists find rich delight in reading James's penetrating analysis of the human mind, *Principles of Psychology* (1890). It was the most influential book in the early history of psychology, and many of its central ideas have held up over time.

A core idea James had that remains a central pillar of psychology today is that the mind is much more complex than its elements and therefore cannot be broken down. For instance, he noted that the mind consists of an everchanging, continuous series of thoughts. This [stream of consciousness](#page-32-0) is the product of interacting and dynamic stimuli coming from both inside our heads, such as the decision of what to have for lunch, and outside in the world, such as the smell of pie wafting from downstairs. Because of this complexity, James argued, the mind is too complex to understand merely as a sum of separate parts, such as a decision-making unit, a smelling unit, and so forth. Trying to understand psychology like that, he said, would be like people trying to understand a house by studying each of its bricks individually. More important to James was that the bricks together form a house and that a house has a particular function (i.e., as a place where you can live). The mind's elements matter less than the mind's usefulness to people.

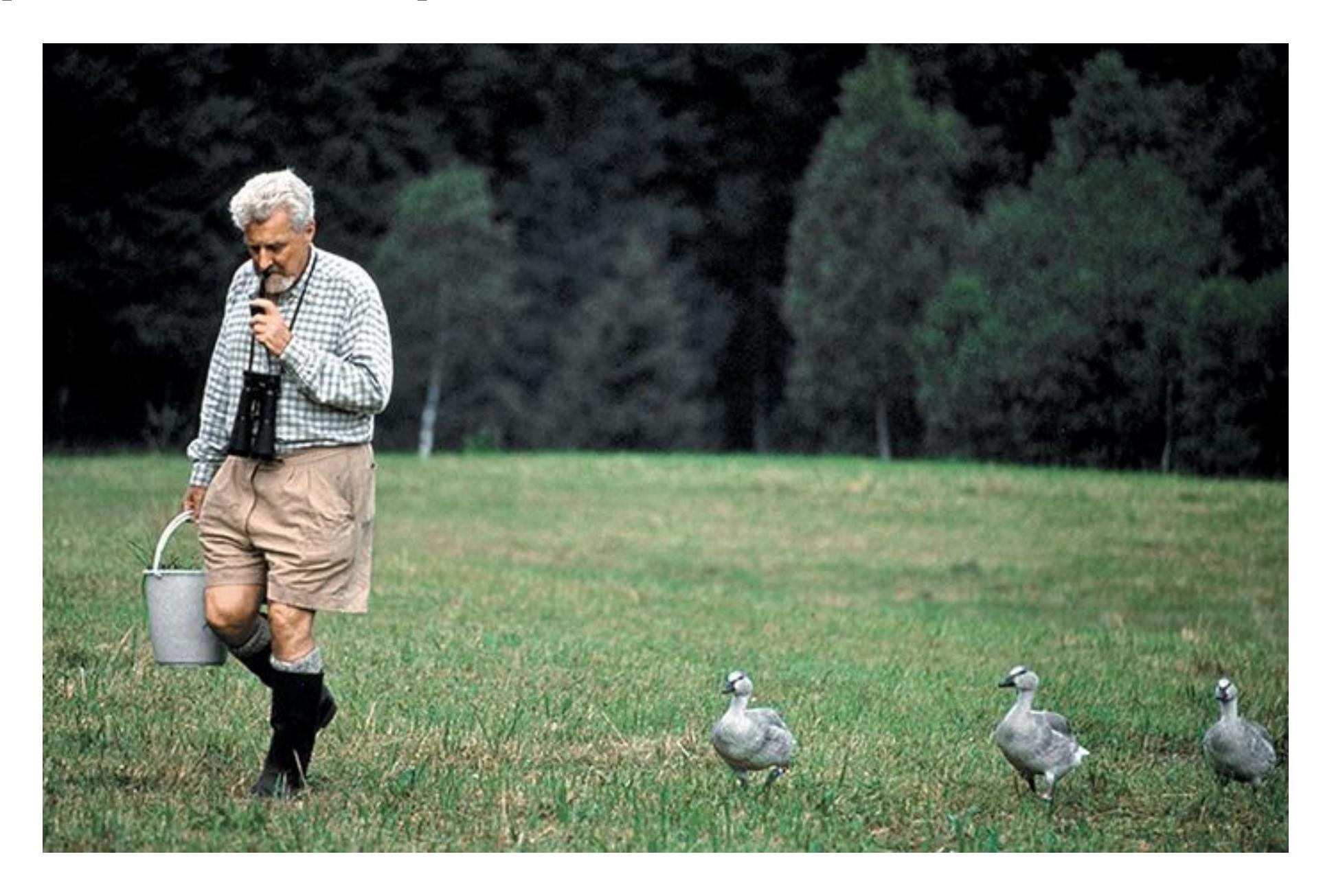

James argued that psychologists ought to examine the functions served by the mind—how the mind operates. According to his approach, which became known as [functionalism](#page-32-1), the mind came into existence over the course of human evolution. It works as it does because it is useful for preserving life and passing along genes to future generations. In other words, it helps humans *adapt* to environmental demands.

Nowadays, psychologists take for granted that any given feature of human psychology serves some kind of purpose. Some features, particularly those that are common to all humans (e.g., sensation and perception), are likely to have evolved through the evolutionary process of [natural selection,](#page-32-2) by which features that are adaptive (that facilitate survival and reproduction) are passed along and those that are not adaptive (that hinder survival and reproduction) are not passed along. Language is a good example, as it is easy to see how the ability to represent and communicate ideas in social groups would be beneficial for human survival: just try communicating to your brother without using words that the third tree on the left about a quarter of a mile down the road has the best apples. Other features, particularly those that are specific to a culture or an individual, probably did not evolve through natural selection but might still be functional. Cultural traditions, such as religious rules against eating certain types of foods, or personal quirks, such as nail biting, are viewed within psychology as "functional" in the sense that they arose to solve a problem: Food prohibitions can protect against illness, and nervous habits can be ways people learn to reduce their anxiety.

**According to William James's functionalism, why should psychologists focus on the operations of the mind?**

**Answer:** The mind is too complex to understand as a sum of separate parts.

# **Glossary**

# stream of consciousness

A phrase coined by William James to describe each person's continuous series of ever-changing thoughts.

# functionalism

An approach to psychology concerned with the adaptive purpose, or function, of mind and behavior.

# natural selection

In evolutionary theory, the idea that those who inherit characteristics that help them adapt to their particular environments have a selective

advantage over those who do not.

# 1.7 The Field of Psychology Spans the Range of Human Experience

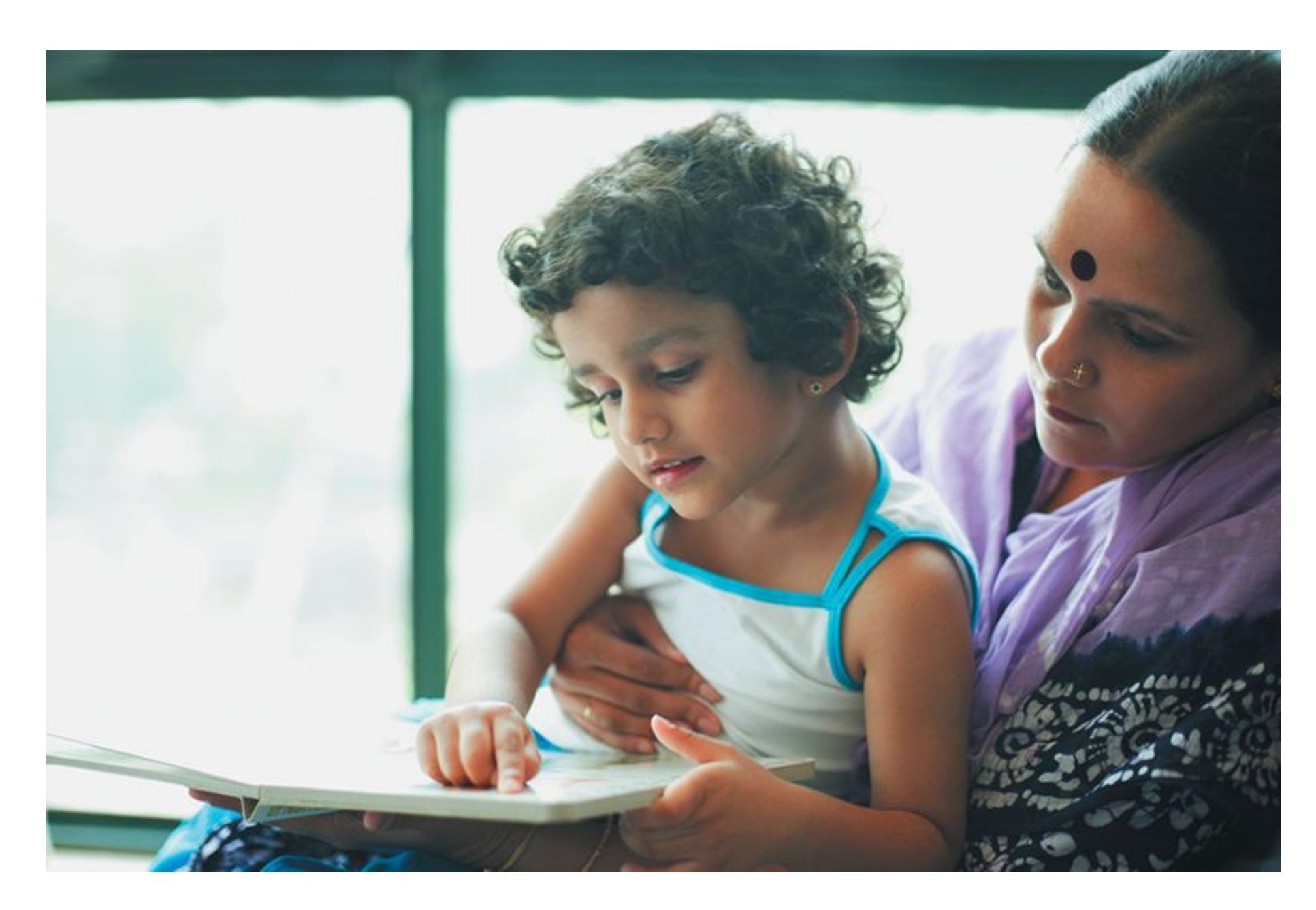

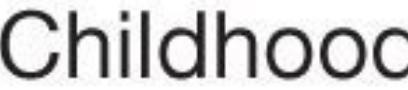

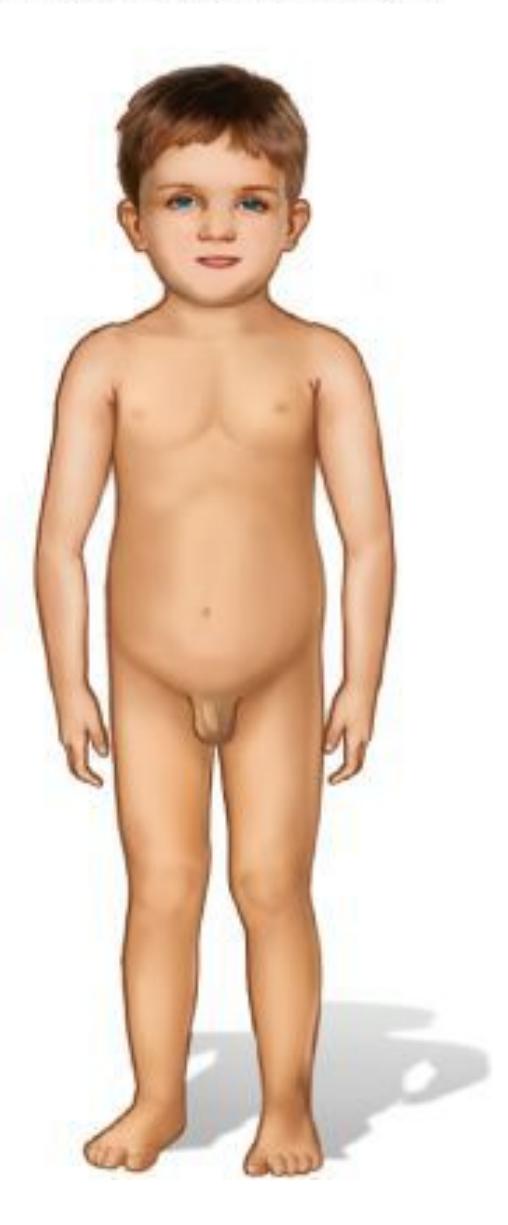

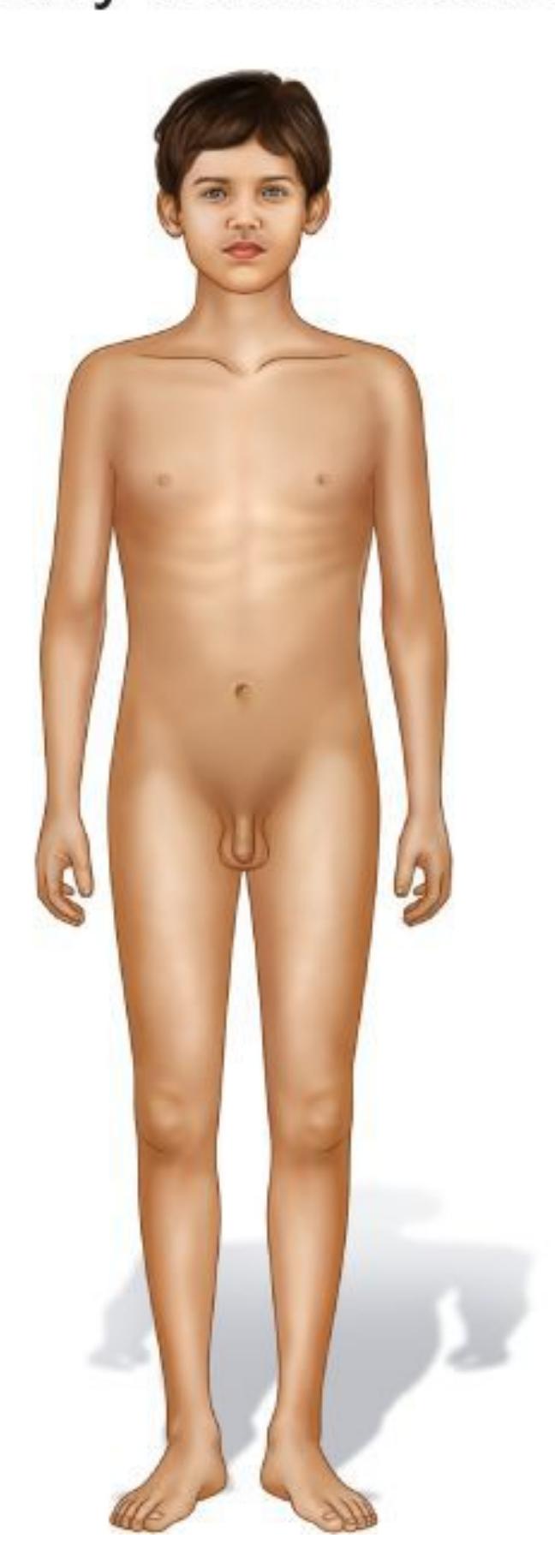

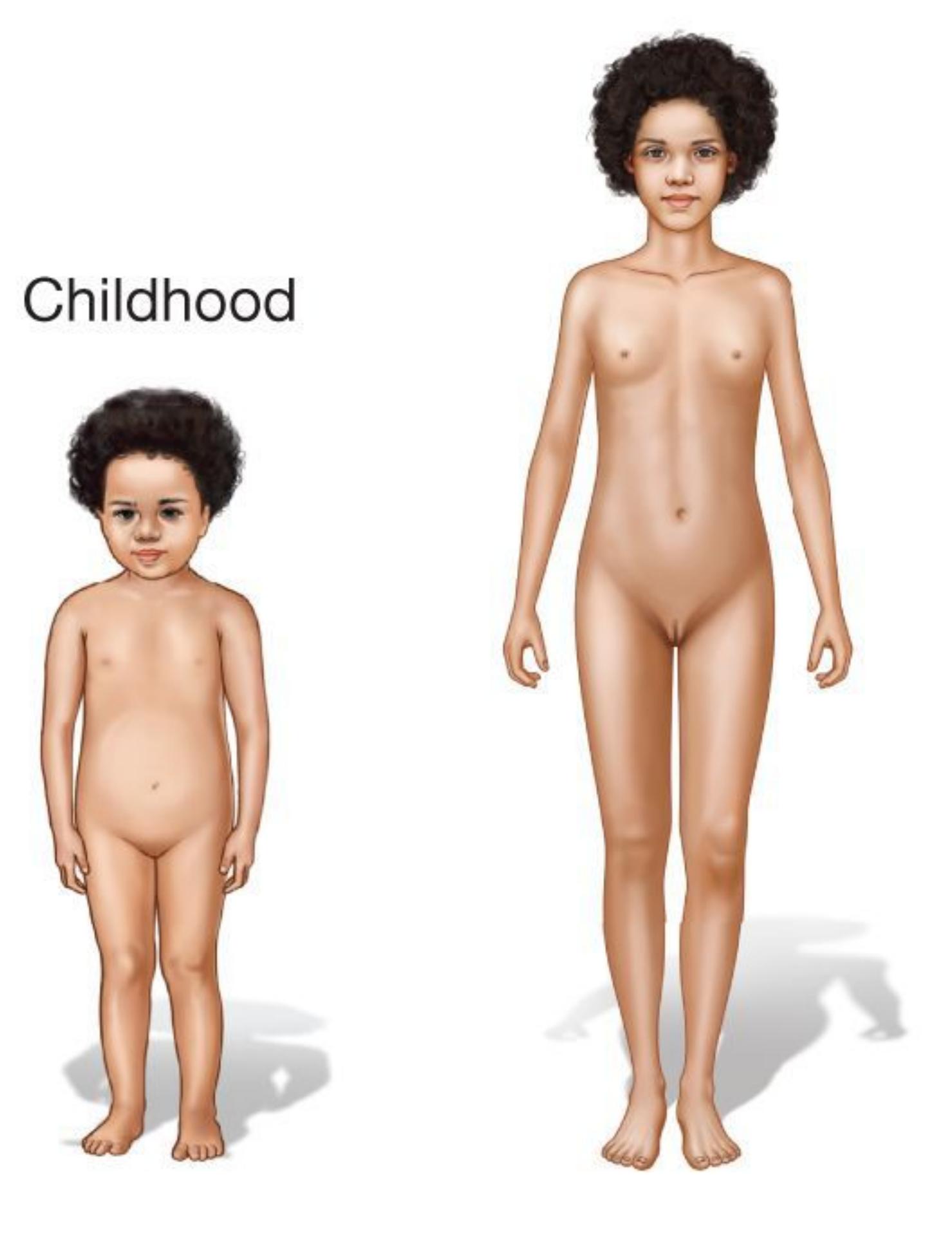

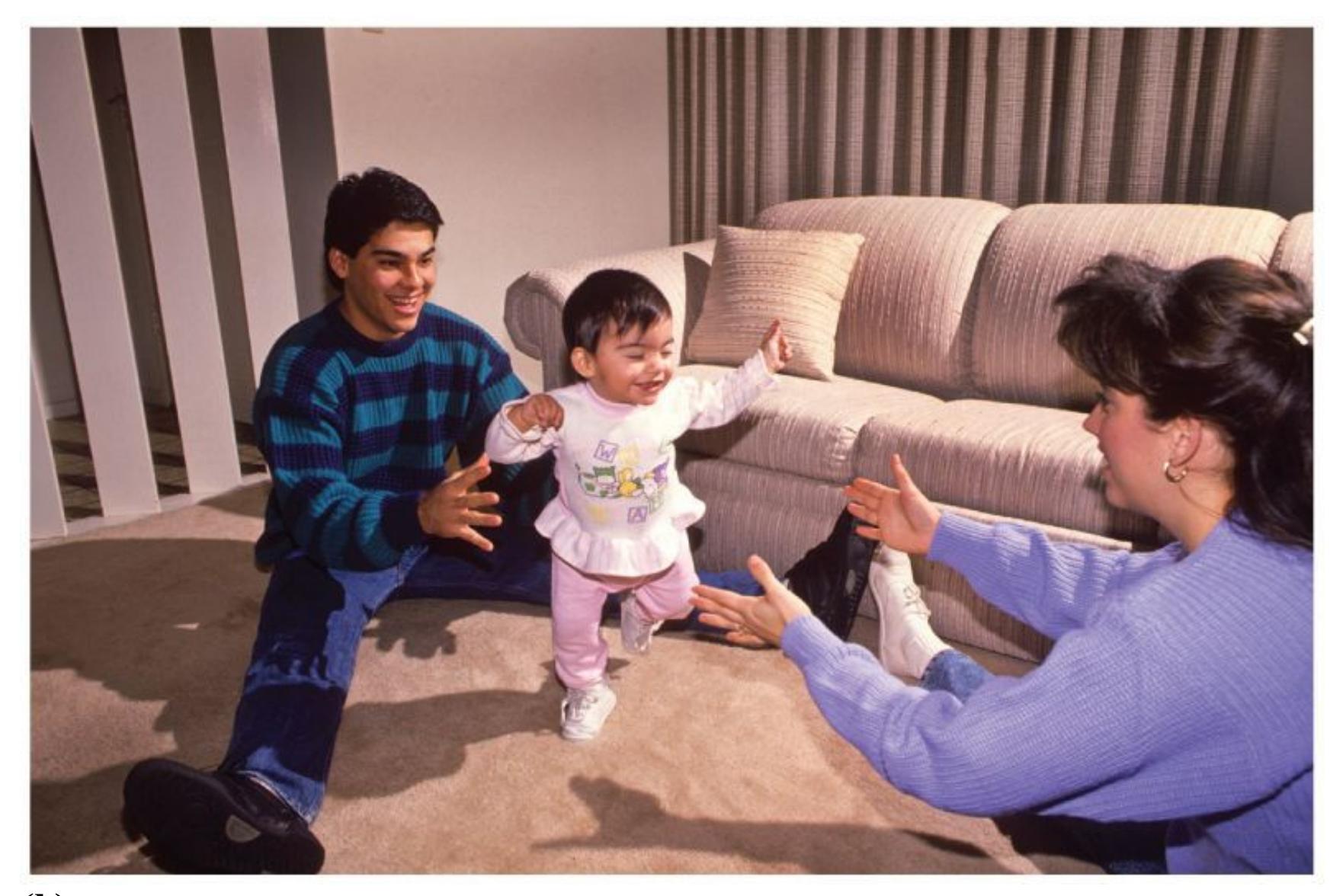

Psychologists are interested in mental phenomena ranging from basic sensory and brain processes to abstract thoughts and complex social interactions (**FIGURE 1.11**). Those topics are universal to humans, but the way we experience sensations, thoughts, feelings, and so forth can vary dramatically within an individual person and across people. Consider, for example, your own emotional range within a day when you were a toddler compared to now, or what a refugee of the Syrian civil war would consider to be a stressful event compared with a typical North American undergraduate student.

**FIGURE 1.11 Employment Settings for Psychologists**

This chart shows the types of settings where psychologists work, based on a survey of those obtaining a doctorate or professional degree in psychology in 2017 (American Psychological Association, 2018).

After decades of focusing on a relatively narrow slice of the world population, the field of psychology is finally beginning to increase its [diversity and inclusion.](#page-42-0) The field views as critical to its mission not only racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity but also diversity in terms of age, ability, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and immigration status, among other features. As part of this shift toward a broader and more central view of diversity and inclusion, the field is moving away from viewing cultural psychology as an area unto itself. Culture and many other forms of diversity are becoming integral to all areas of psychology as researchers learn that key developmental, social, personality, cognitive, and clinical phenomena can vary considerably as a function of culture and personal experiences. The internet allows researchers to gather data from across the globe, and it is becoming more and more common for research projects to feature samples from several and even dozens of countries. Many psychology departments now ask applicants to professor positions to include as part of the application package a statement about how their research considers diversity and inclusion. The field still lacks diversity in many ways, but this progress shows that there is motivation to change.

Psychologists began to specialize in specific areas of research as the kinds of human experiences under investigation by psychological science broadened over the years. **Table 1.1** describes some of the most popular areas of specialization in psychology. The psychology departments at most universities have clusters of professors in several of these areas. Some departments offer master's and doctorate degrees with these specializations.

**Table 1.1** Areas of Specialization in Psychology

| AREA | FOCUS | SAMPLE QUESTIONS | CHAPTER |

|---------------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|---------|

| Clinical | The area of psychology that seeks to understand, characterize, and treat | Are there underlying psychological | 14 |

| | | | 15 |

| | mental illness is called

clinical psychology.

Clinical psychology is

one of the most common

specializations in the

field. Advanced degrees

in clinical psychology

focus on research,

clinical work/therapy, or

a blend of the two. | or biological

causes across

different

mental

disorders?

What are the

most effective

ways to treat

personality

disorders?

Can

mindfulness

meditation

reduce

psychological

distress in

anxiety

disorders? | |

| Cognitive | Laboratory research in

cognitive psychology

aims to understand the

basic skills and processes

that are the foundation of

mental life and behavior.

Topics such as attention,

memory, sensation, and

perception are within the

scope of cognitive

psychology. | Why is

multitasking

harder than

working on

tasks one after

the other?

How does

damage in

particular

areas of the

brain alter

color

perception but

not motion

perception?

3

4

5

6

7

8 | |

| | | Do some

people learn

more quickly

than others to

associate

cause and

effect? | |

| Cultural | Cultural psychology

studies how cultural

factors such as

geographical regions,

national beliefs, and

religious values can have

profound effects on

mental life and behavior.

A major contribution of

cultural psychology is to

highlight the profound

ways that the samples

used in psychological

studies can influence the

results and their

implications. Cultural

psychology is the area

most closely linked to the

adjacent fields of

sociology and

anthropology. | Why does the

southern

United States

have the

highest rate of

per capita gun

violence in

the country?

Do people

think of

themselves in

fundamentally

different ways

depending on

where they

were raised?

Does thinking

about a

forgiving

versus

vengeful deity

influence

moral

behavior such

as lying? | 1

2 |

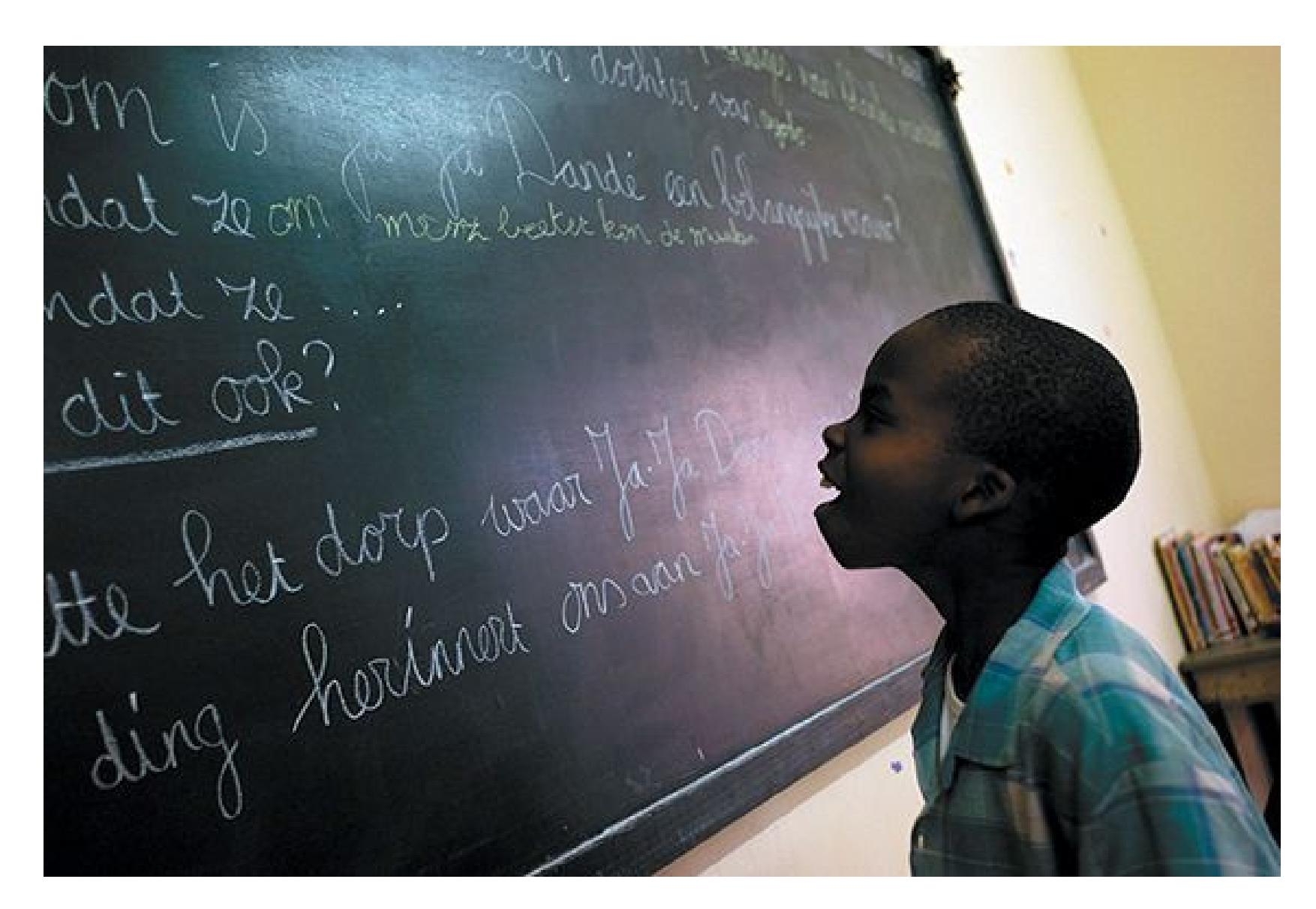

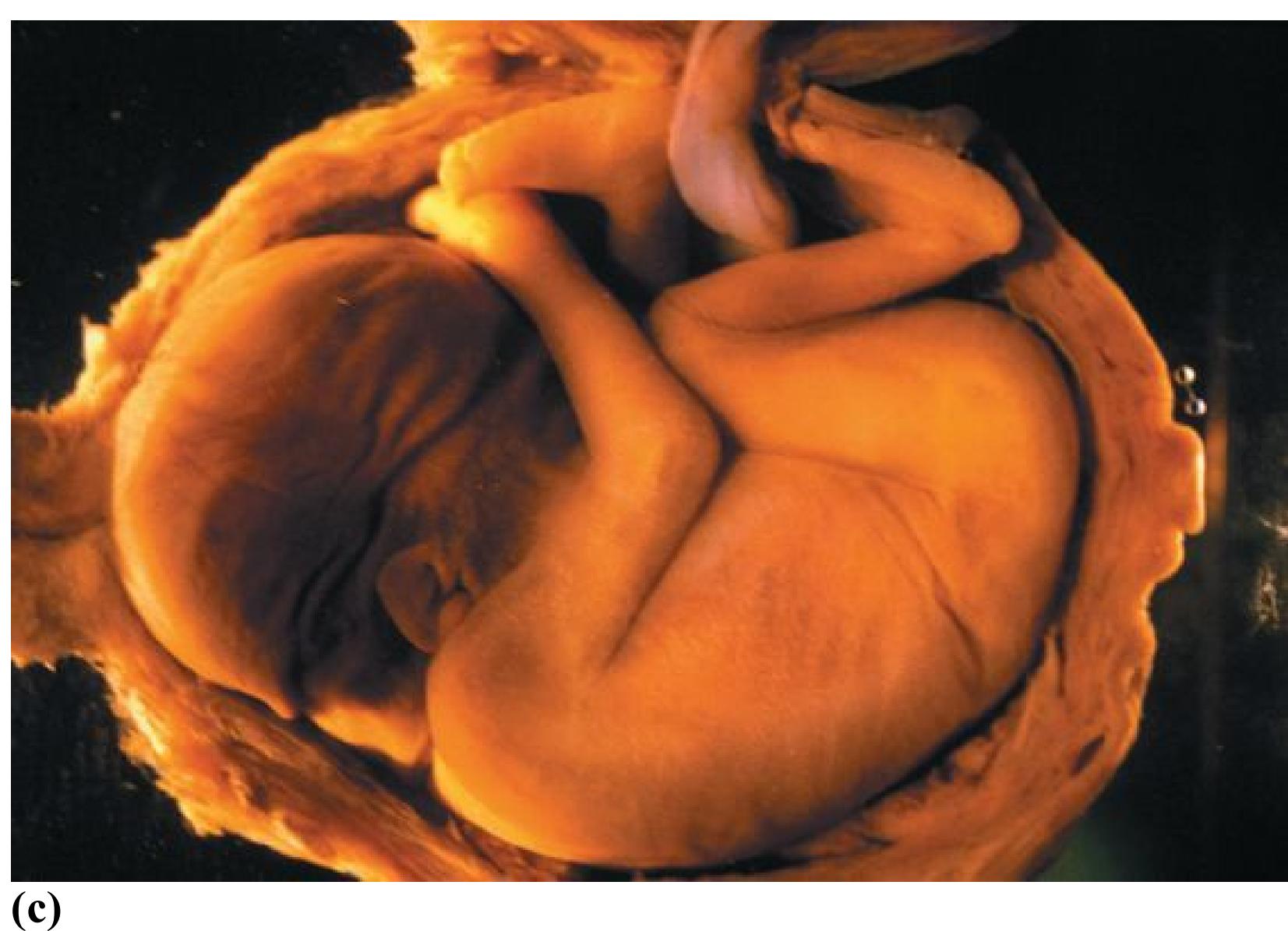

| Developmental | Developmental

psychology studies how | How does

stress | 9 |

| humans grow and develop from the prenatal period through infancy and early childhood, through adolescence and early adulthood, and into old age. Developmental psychology encompasses the full range of topics covered by other areas in psychology, focusing on how experiences change across the life span and the periods in life when they are particularly important. | experienced by the mother alter the developing immune system of a fetus in utero? Why do children learn languages more easily than adults? In what ways is risk-taking functional for adolescents as they seek to establish themselves in new social groups? | | |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|----|

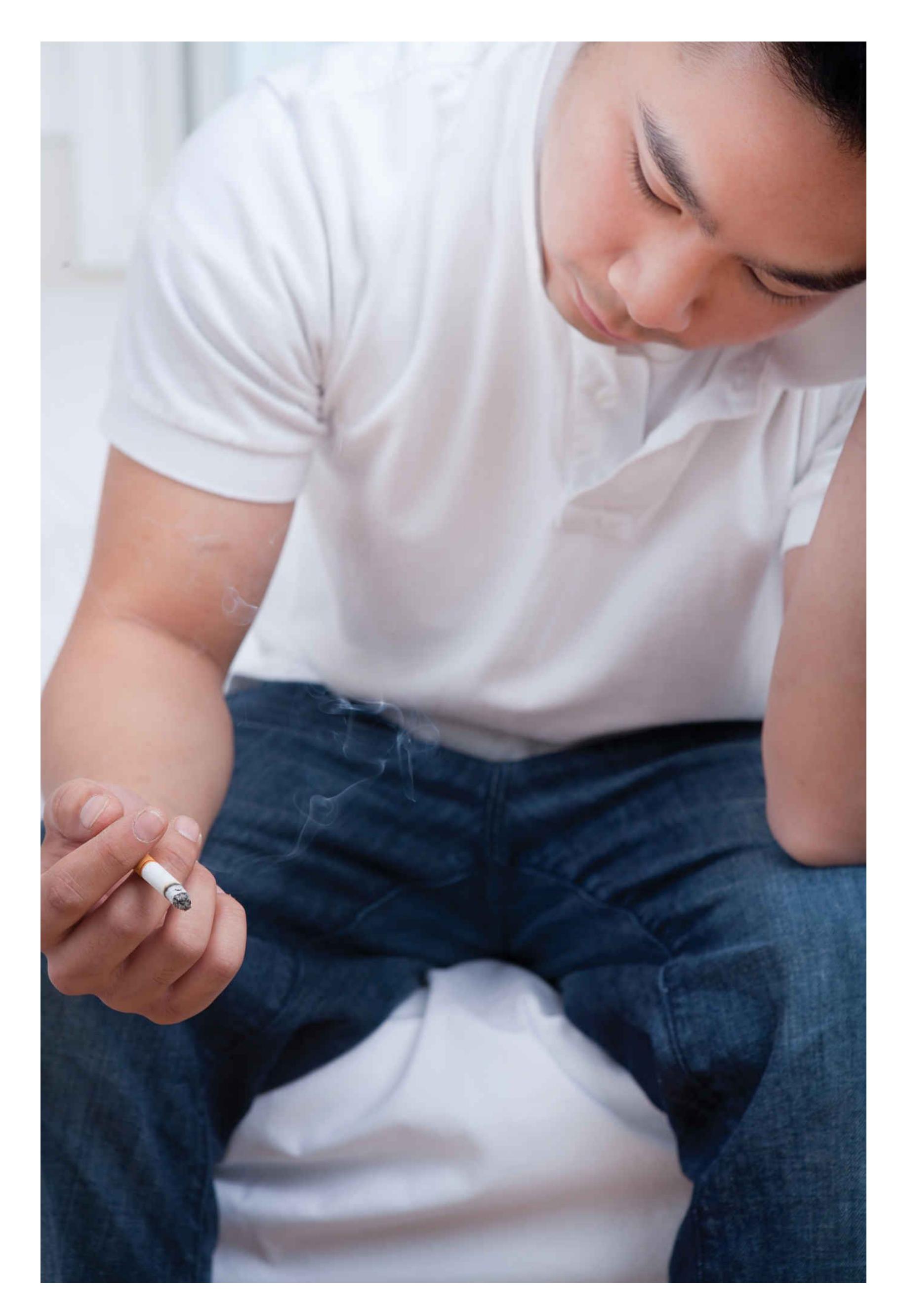

| Health | Health psychology is concerned with how psychological processes influence physical health and vice versa. Psychological factors such as stress, loneliness, and impulsivity can powerfully influence a range of health disorders and even mortality. In contrast, optimism, social support, and conscientiousness can | How can strong friendships protect or "buffer" us from the harmful effects of stress? Does memory training help people resist temptations such as | 11 |

| | promote healthy

behaviors. | excessive

alcohol or

tobacco use?

When does

experiencing

discrimination

increase the

likelihood of

heart disease? | |

|---------------------------|---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|--|

| Industrial/Organizational | Industrial/organizational

(I/O) psychology

explores how

psychological processes

play out in the workplace.

This field is one of the

more pragmatic

specializations in

psychology because it

speaks to real-world

problems such as dealing

with interpersonal

conflicts at work and

organizational change.

I/O psychology blends

social-personality

psychology approaches

with principles from

management,

communication, and

marketing. Research on

I/O psychology happens

in organizational settings

as well as in psychology

departments and business

schools. | What are

ways that

organizations

can increase

employee

motivation in

stressful

times?

How can

critical

feedback be

provided to

managers so

that it is gentle

yet results in

behavior

change?

What types of

people should

organizations

hire into

specialized

versus more

general roles? | |

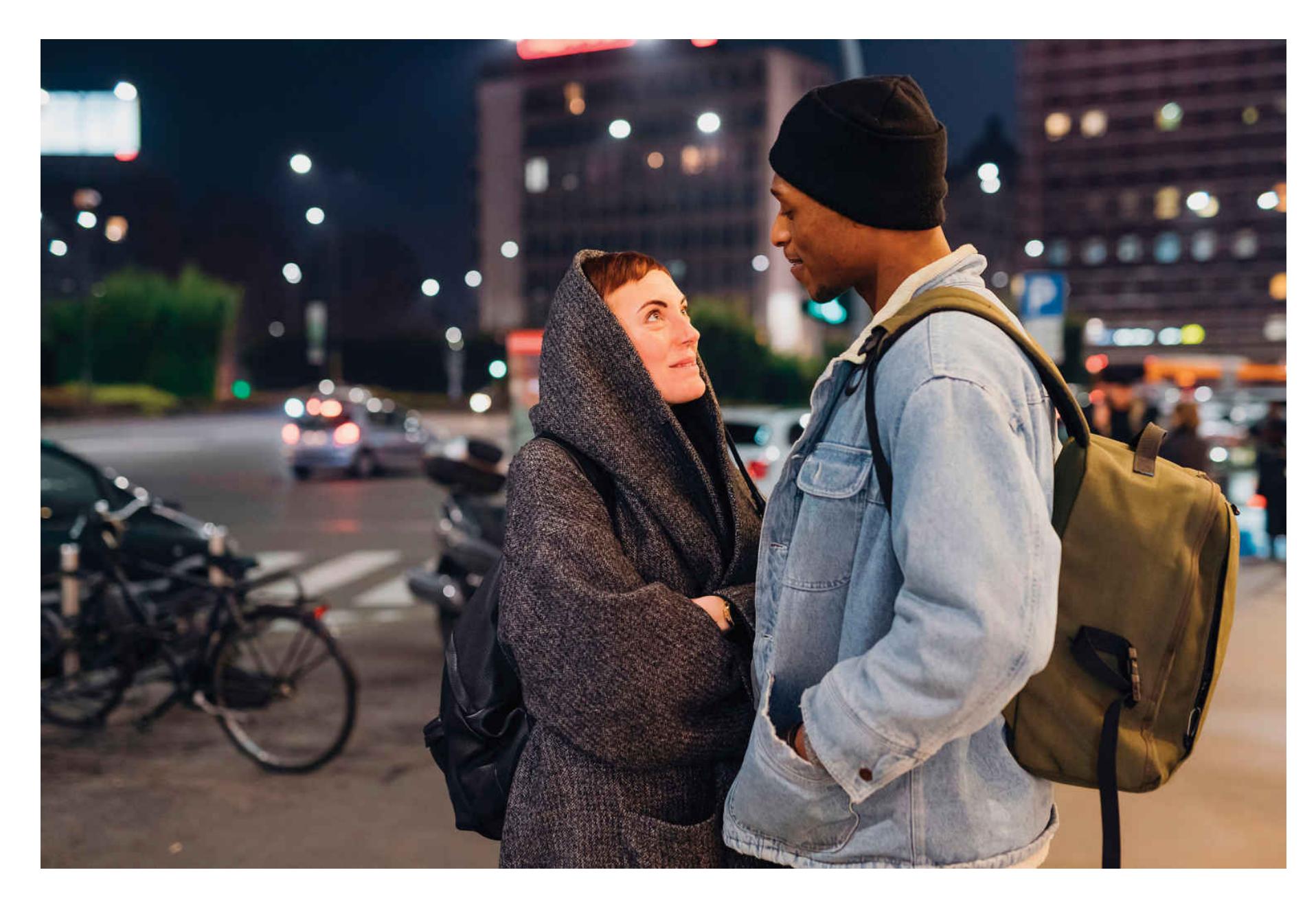

| Relationships | The quality of our close

relationships, including

romantic partnerships and

intimate friendships, is

the most consistent

predictor of overall

happiness and well-

being, and relationship

issues are the most

common reason people

seek psychotherapy.

Close relationships

psychologists research

our intimate relationships,

properties that make them

succeed or fail, and the

two-way effects between

intimate relationships and

other aspects of our lives. | What

differentiates

long-lasting

marriages

from those

that end in

early divorce?

In what ways

do romantic

partners

influence each

other's goal

pursuit?

Is it important

for

relationship

satisfaction

that partners

"match" on

certain

personality

traits? If so,

which ones? | 12 |

|--------------------|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|----------------|

| Social-Personality | Social-personality

psychology is the study of

everyday thoughts,

feelings, and behaviors—

and the factors that give

rise to them. Social-

personality psychology

focuses on the situational

and dispositional causes

of behavior and the

interactions between

them. Social and

personality psychology | What are the

causes of

stereotyping

and prejudice

and what are

people

understand

and explain

other people's

behaviors? | 10

12

13 |

| were once separate |

|---------------------------|

| fields, but scholars from |

| both sides now recognize |

| that mental life and |

| behavior cannot be fully |

| understood without both |

| pieces and their |

| interaction. |

their effects on victims?

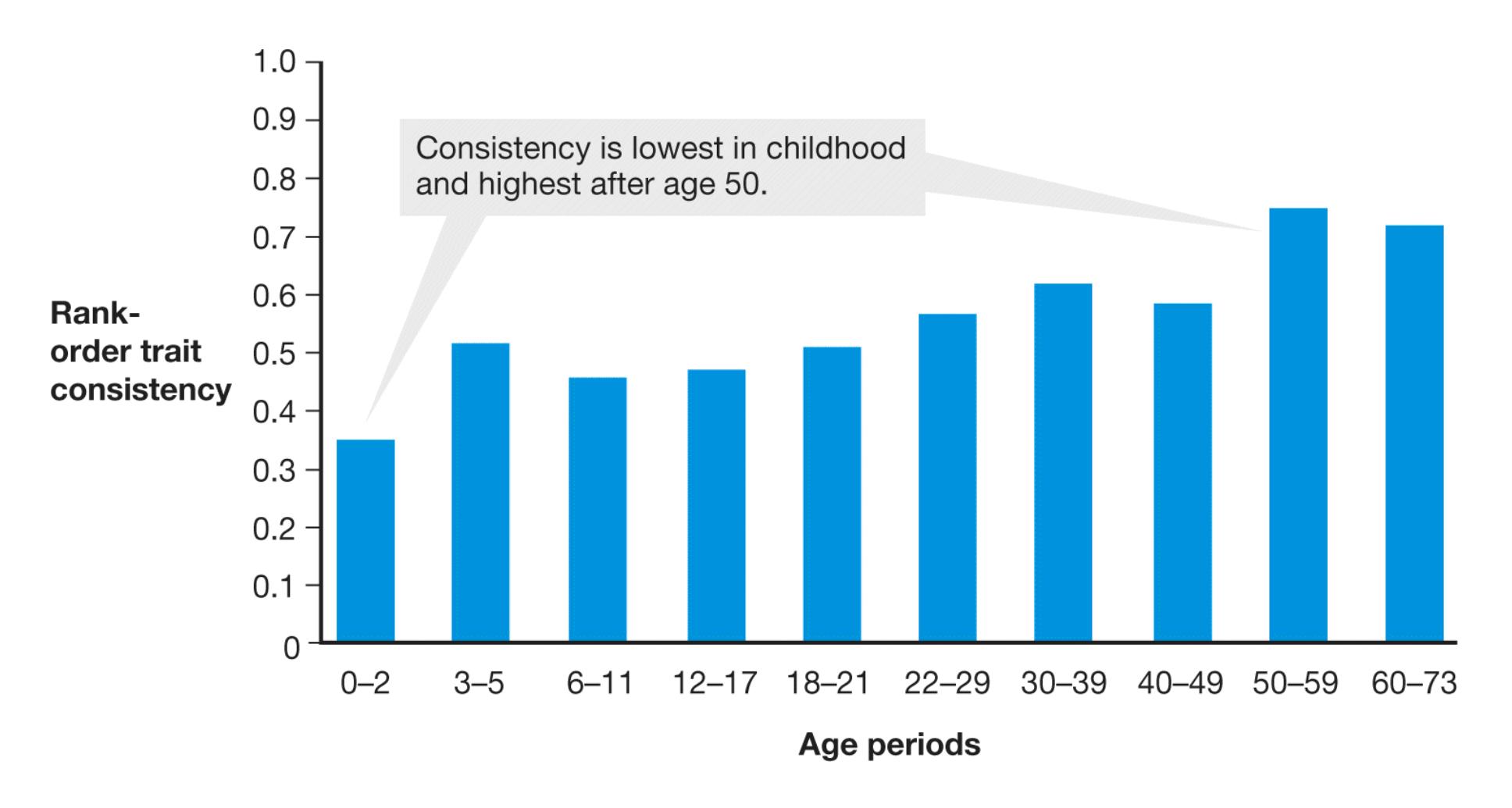

Does personality remain stable across the life span? If not, in what ways does personality change as people age and why?

**Which area of psychology specializes in understanding the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of daily life?**

**Answer:** social-personality psychology

# **Glossary**

# diversity and inclusion

The value and practice of ensuring that psychological science represents the experiences of all humans.

# What Are the Latest Developments in Psychology?

# Learning Objectives

- Identify recent developments in psychological science.

- Explain how the science of learning can help your performance in class.

In the many decades since psychology was founded, researchers have made significant progress in understanding mind, brain, and behavior. As in all sciences, this wisdom progresses incrementally: As psychologists ask more questions about what is already known, new knowledge springs forth. During various periods in the history of the field, new approaches have transformed psychology, such as when William James prompted psychologists to collect data to study minds. We do not know what approaches the future of psychology will bring, but this section outlines some of the developments that contemporary psychologists are most excited about.

# 1.8 Biology Is Increasingly Emphasized in Explaining Psychological Phenomena

Recent decades have seen remarkable growth in the understanding of the biological bases of mental activities. This section outlines three major advances that have helped further the scientific understanding of psychological phenomena: developments in neuroscience, progress in genetics and epigenetics, and advances in immunology and other peripheral systems.

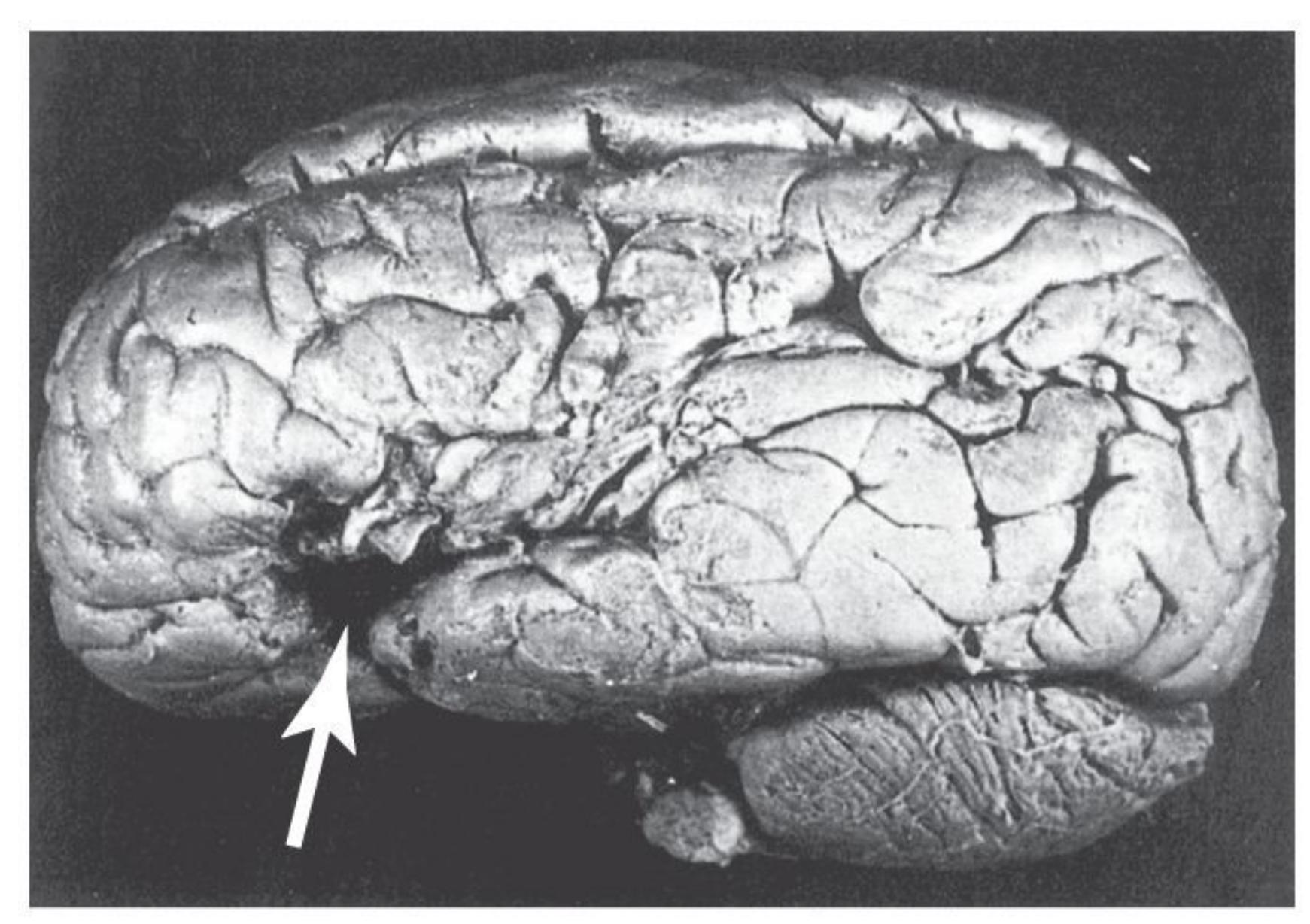

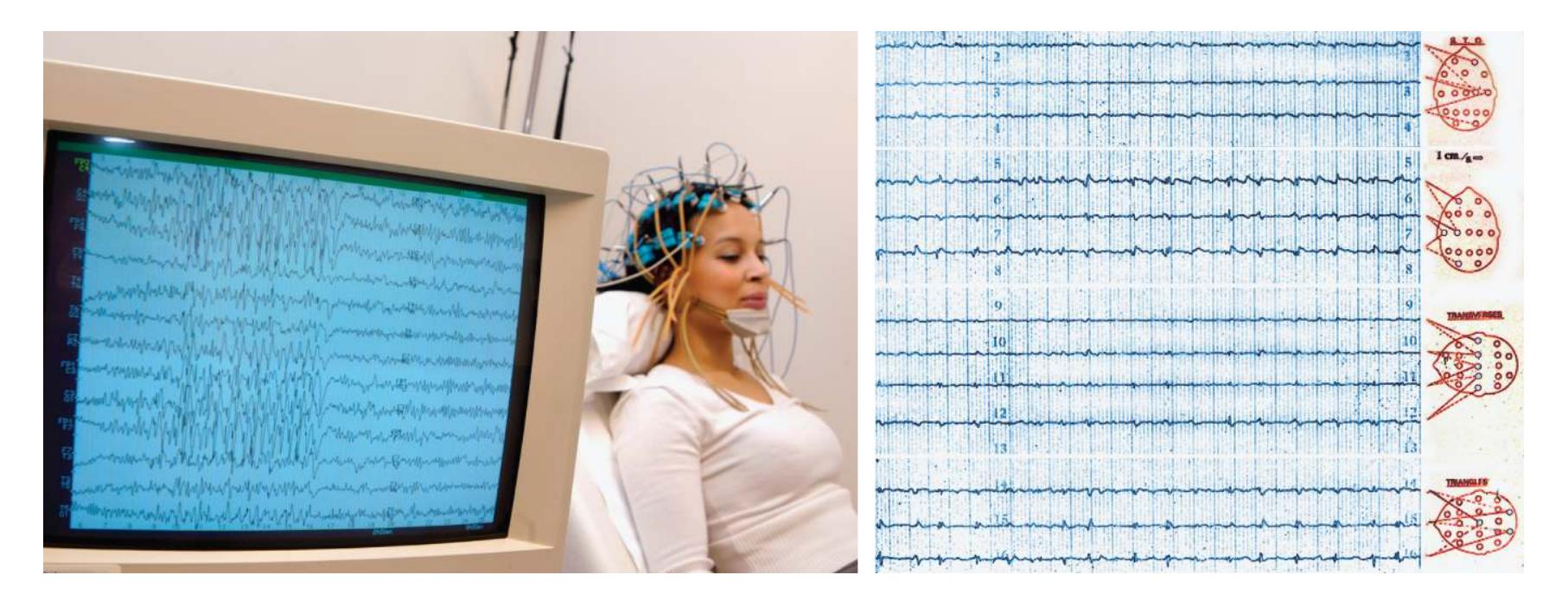

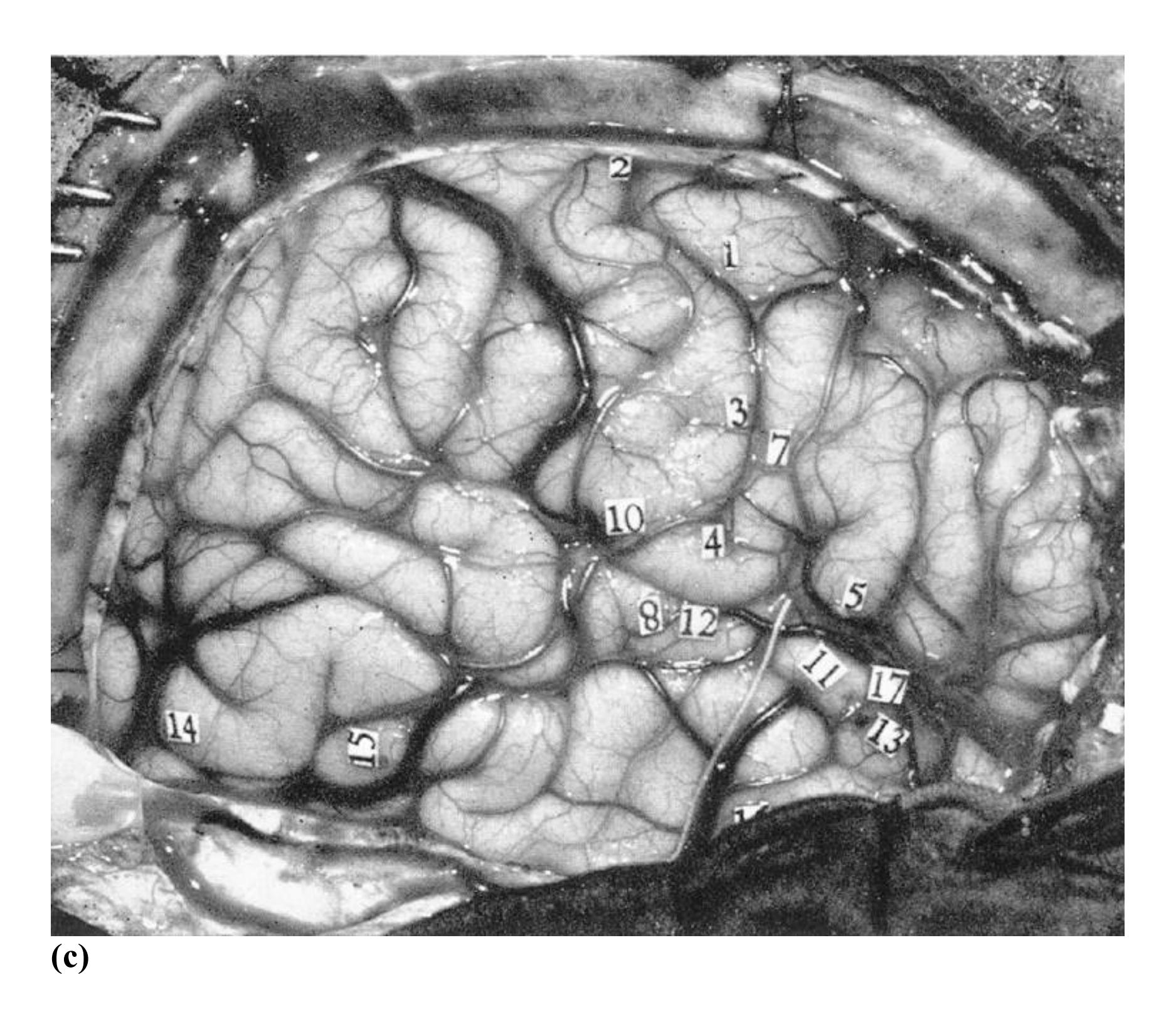

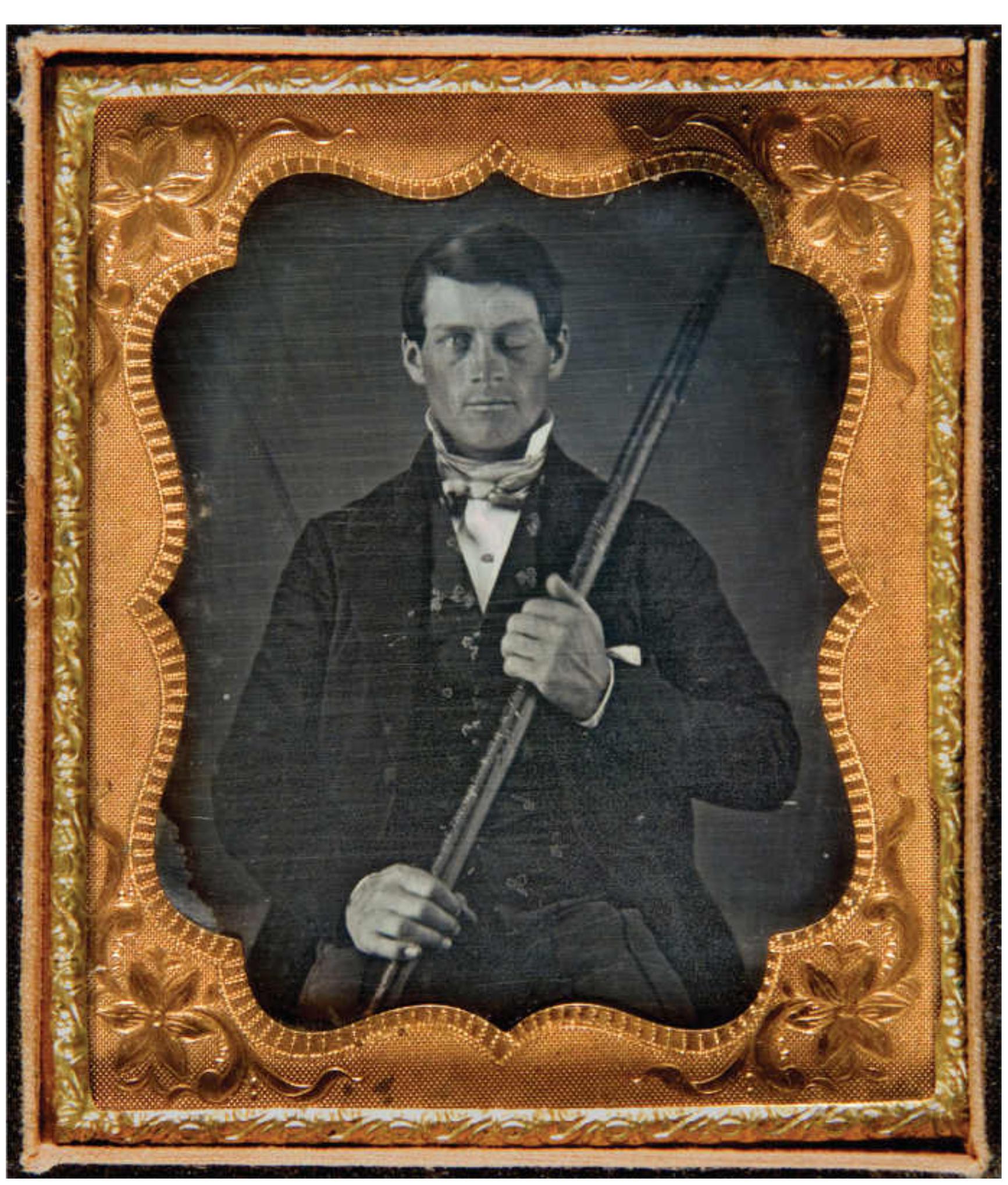

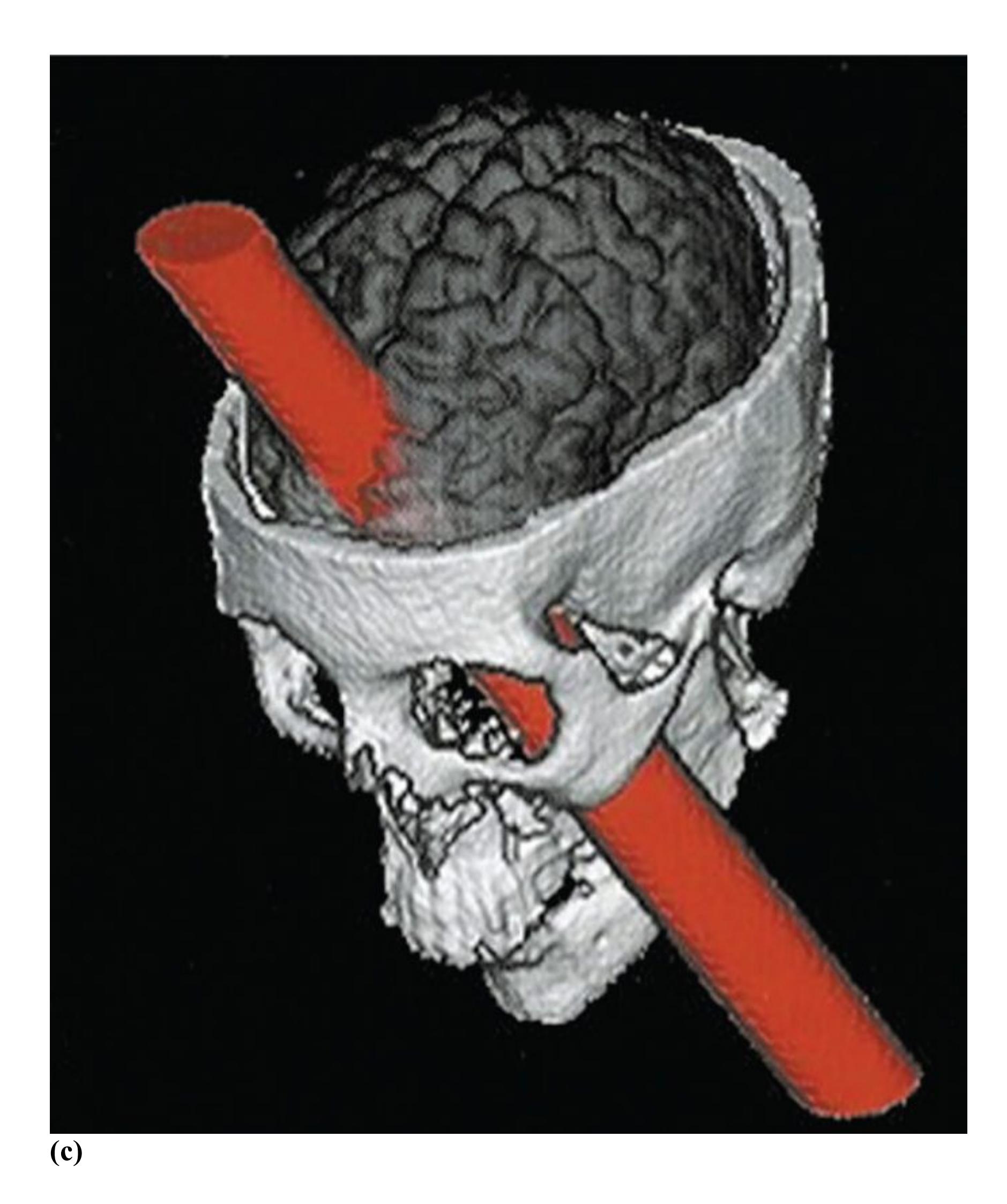

**BRAIN IMAGING** There is a very long history of brain science in psychology. Since ancient times, people have recognized that alterations to the soft mass of tissue between our ears can cause profound changes in mind and behavior. Pioneers such as Pierre Paul Broca discovered that damage to specific regions can correspond to specific changes in parts of our psychology, such as speech and language. But technology such as electroencephalography (EEG), which measures

changes in electrical activity, and now devices that measure subtle changes in the magnetic field caused by changes in blood flow have significantly accelerated progress in brain science.

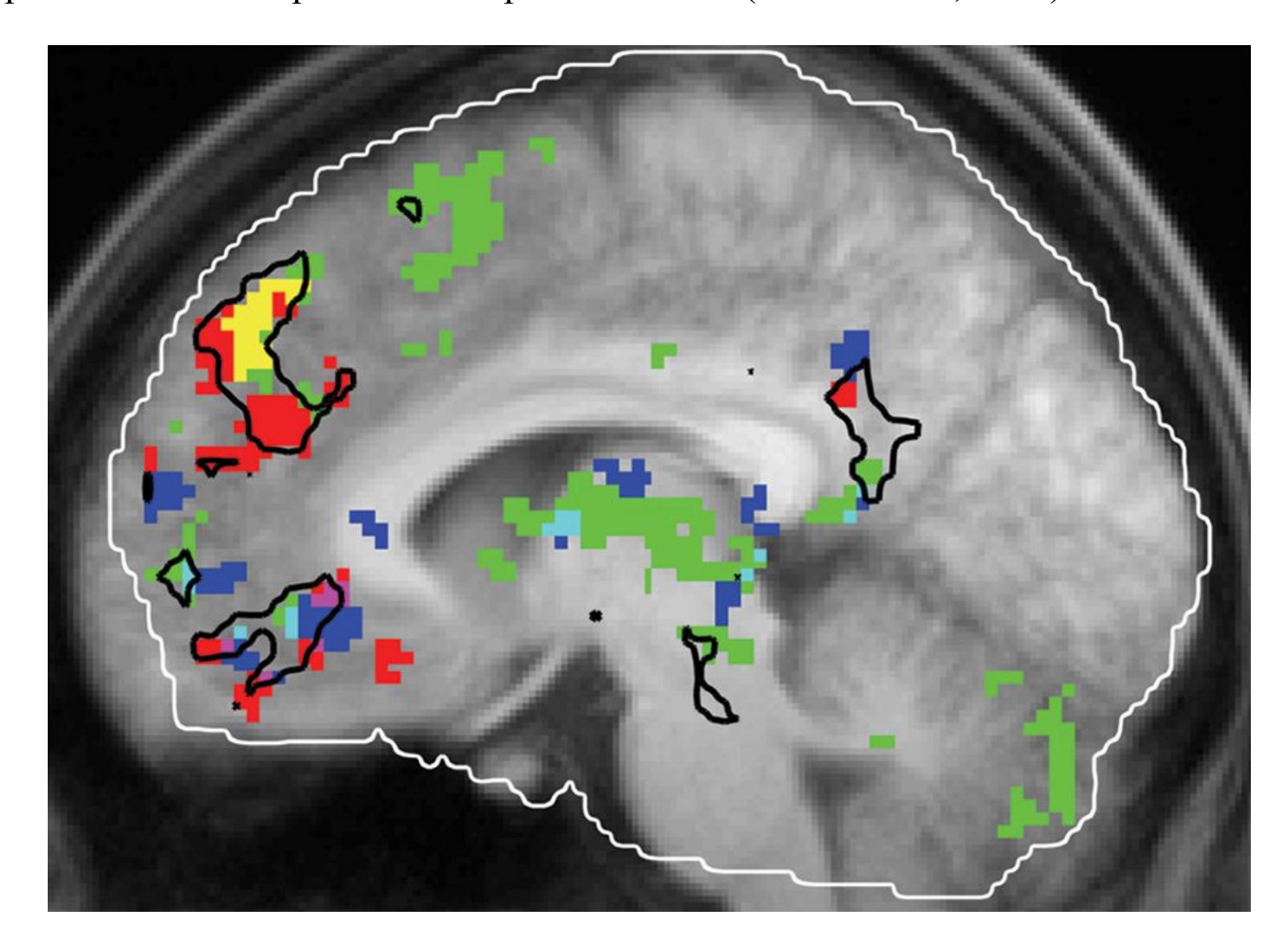

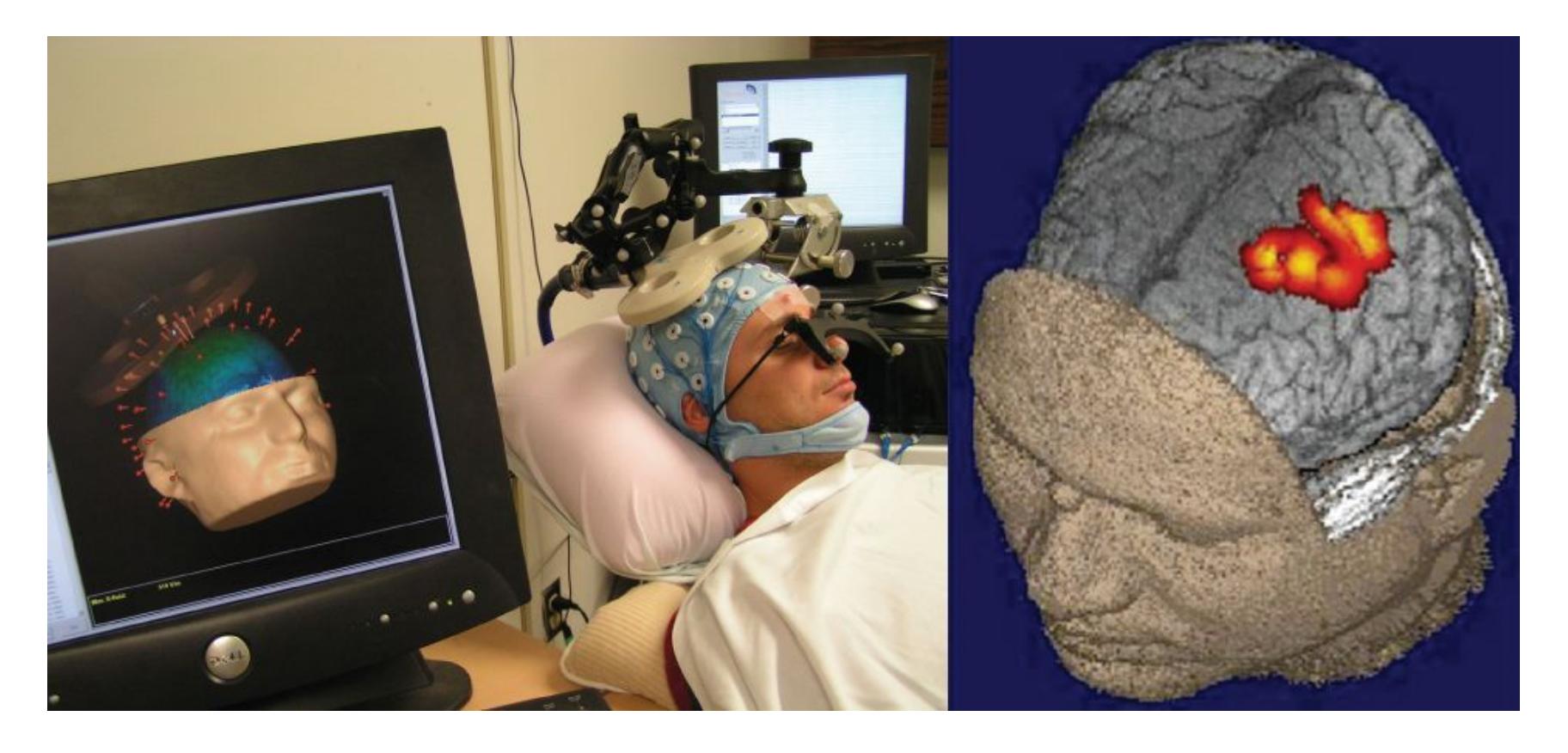

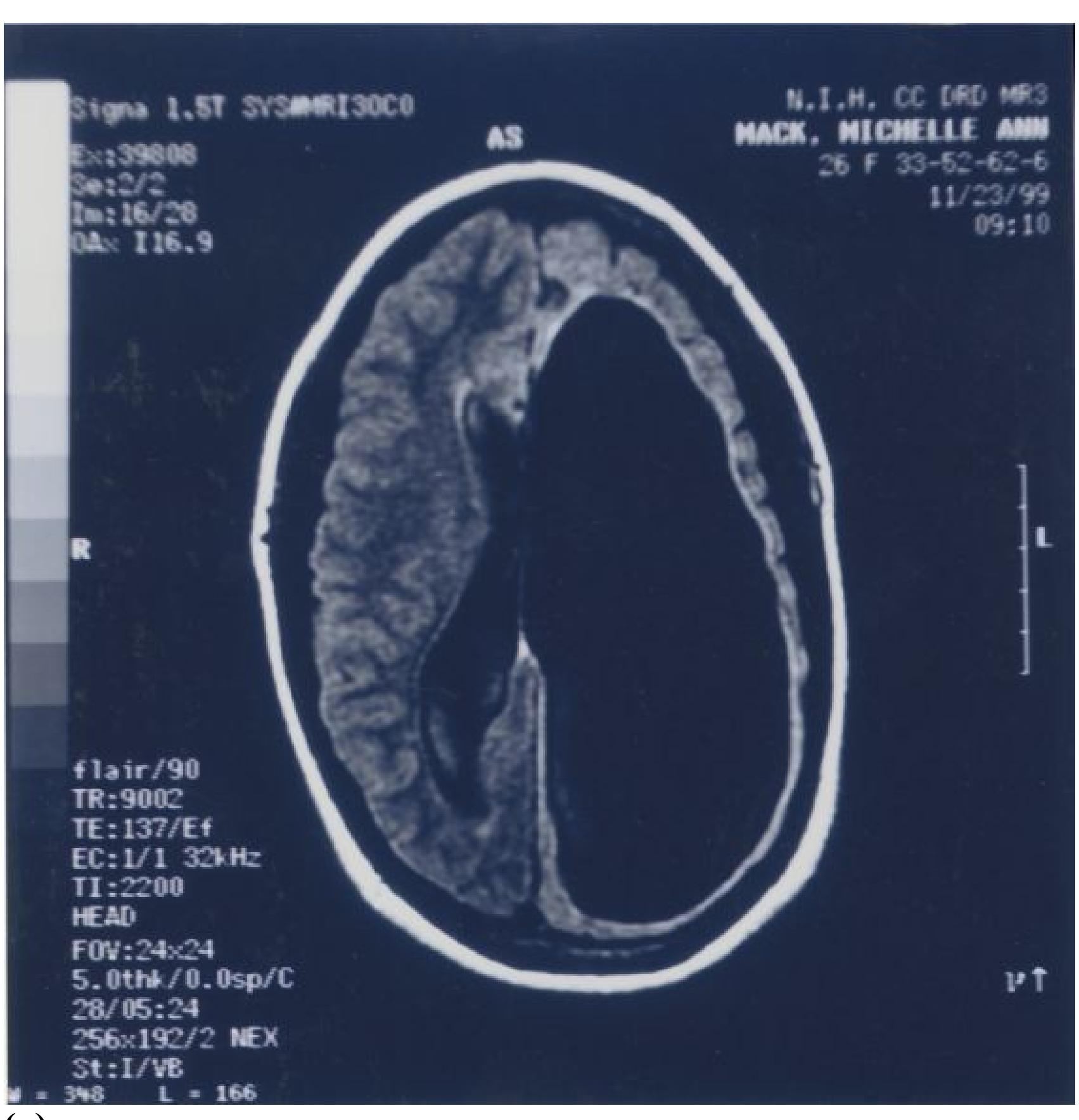

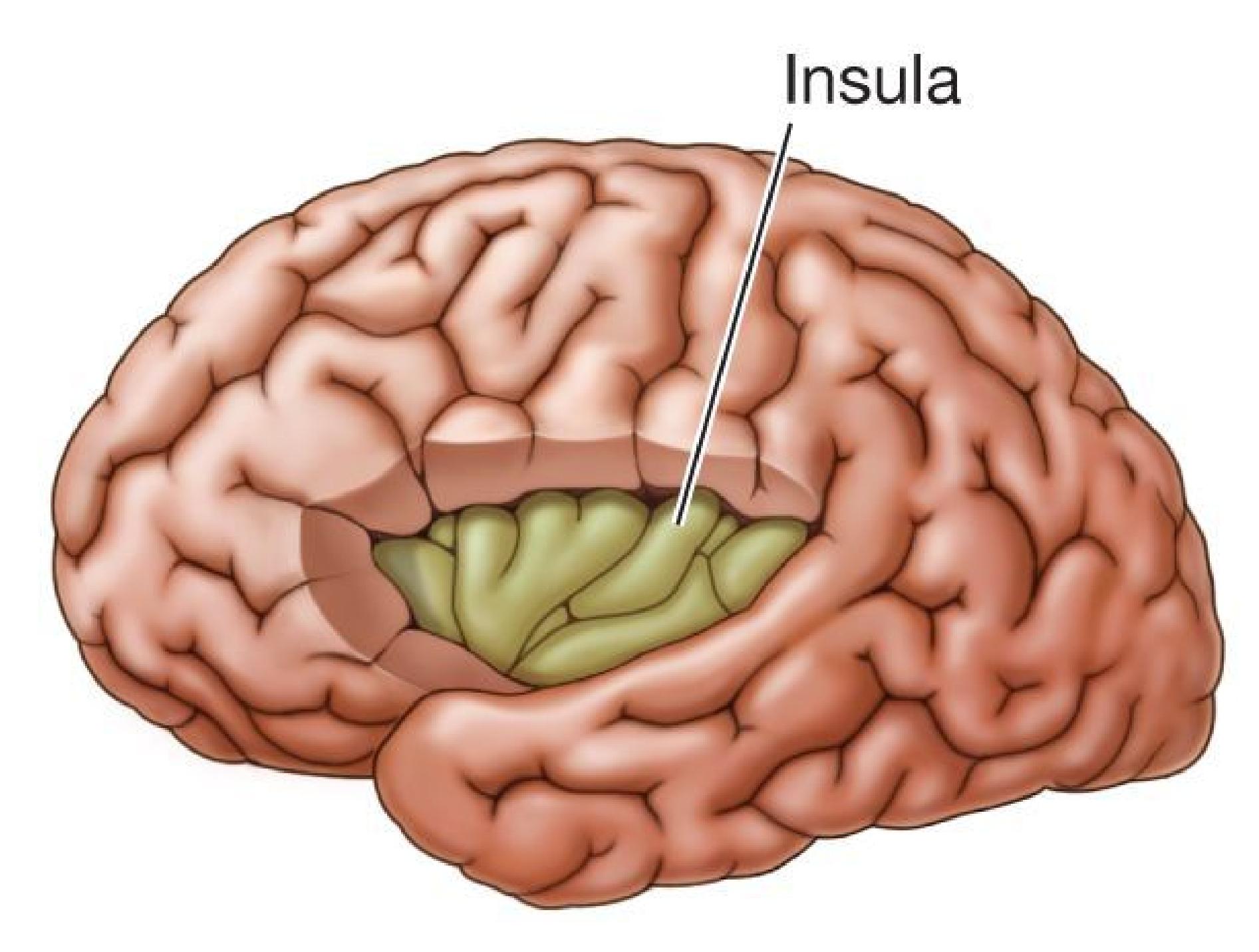

One method, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), enables researchers to study the working brain as it performs its psychological functions in close to real time (**FIGURE 1.12**). Since its development, the progress in understanding the neural basis of mental life has been rapid and dramatic. Knowing where in the brain something happens does not by itself reveal much. However, when consistent patterns of brain activation are associated with specific mental tasks, the activation appears to be connected with the tasks. Earlier scientists disagreed about whether psychological processes are located in specific parts of the brain or are distributed throughout the brain. Research has made clear that there is some *localization* of function. That is, different areas of the brain are specialized for different functions, such as language, control over behavior, and abstract thinking.

**FIGURE 1.12**

**fMRI**

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can reveal changes in brain activation in response to different mental processes.

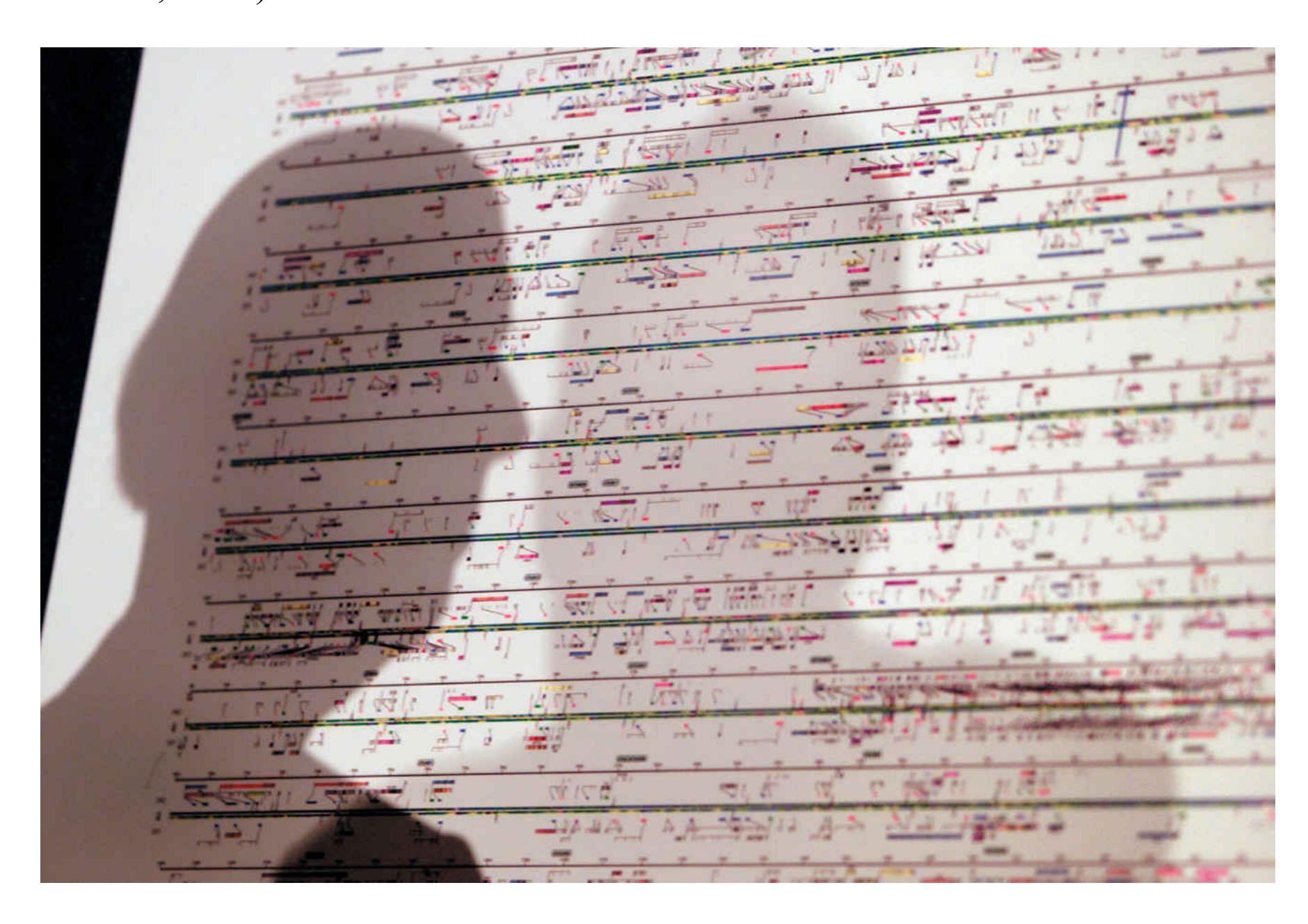

However, many brain regions have to work together to produce complex behaviors and mental activity. One of the greatest contemporary scientific challenges is mapping out how various brain regions are connected and how they work together to produce mental activity. To achieve this mapping, the *Human Connectome Project* was launched in 2010 as a major international research effort involving collaborators at a number of universities. A greater understanding of brain connectivity may be especially useful for understanding how brain circuitry changes in psychological disorders (**FIGURE 1.13**).

**FIGURE 1.13 Brain Connectivity**

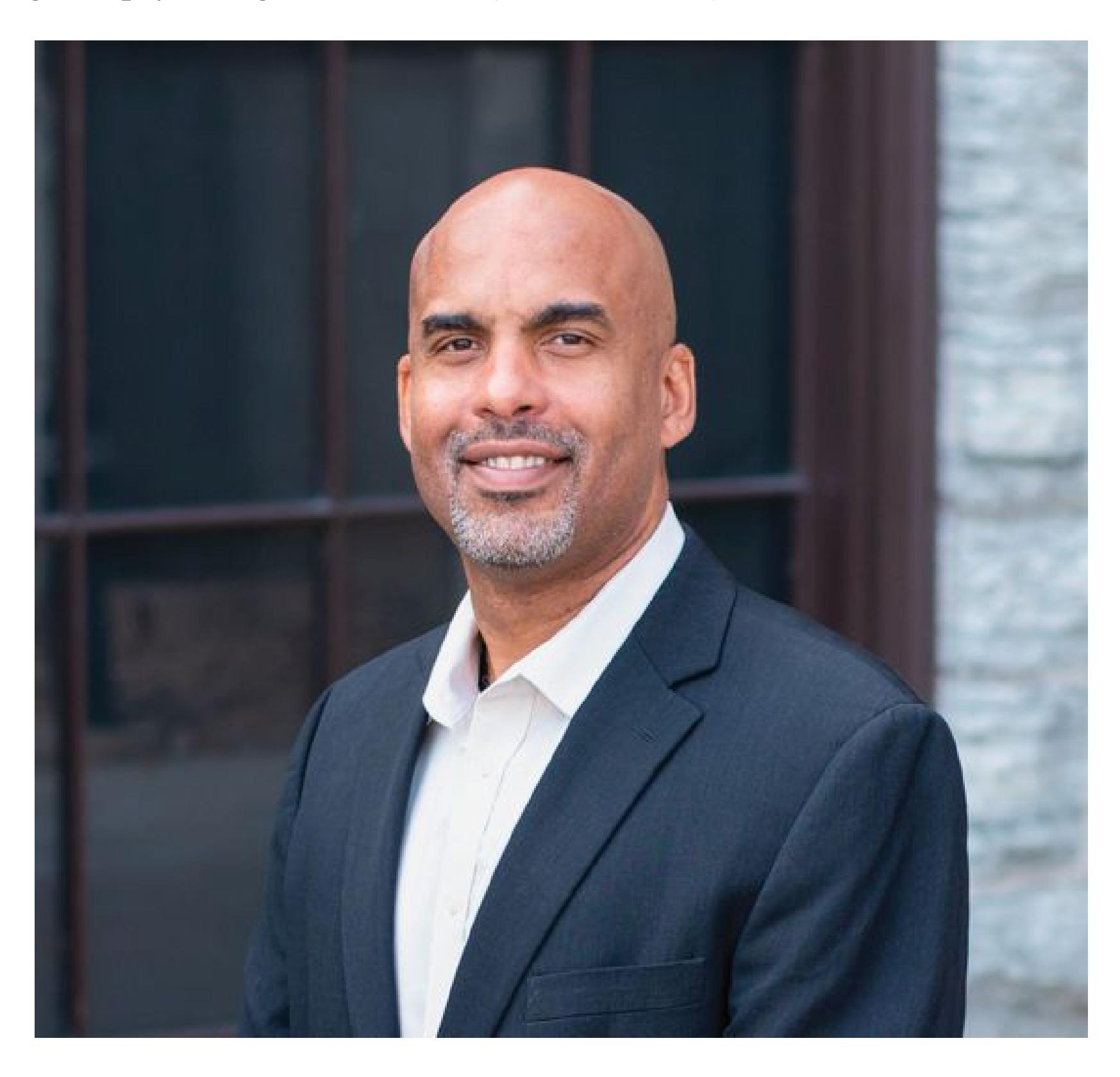

Psychologist Damien Fair received a MacArthur "Genius" Fellowship for his research on the ways parts of the brain are connected to each other and how those patterns of connectivity relate to disorders in children and adolescents.

Neuroscience approaches, such as fMRI, were originally used to study basic psychological processes, such as how people see or remember information. Today, such techniques are used to understand a wide range of phenomena, from how emotions change during adolescence (Silvers et al., 2017), to how people process information regarding social groups (Freeman & Johnson, 2016), to how thinking patterns contribute to depression (Hamilton et al., 2015).

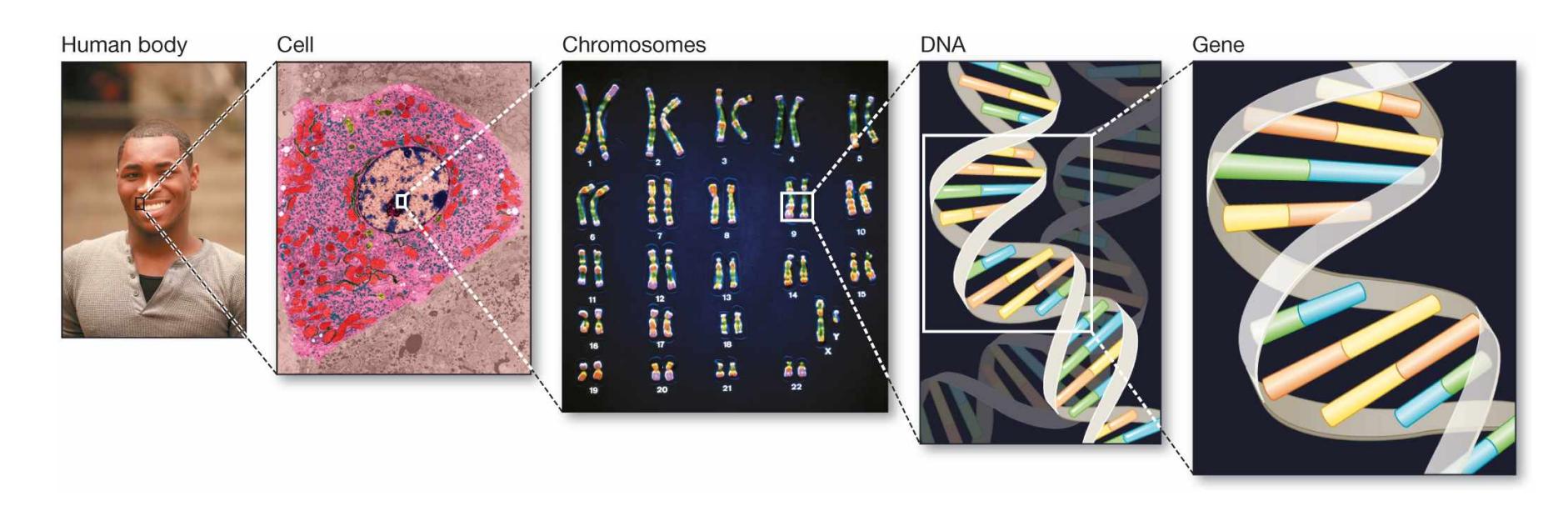

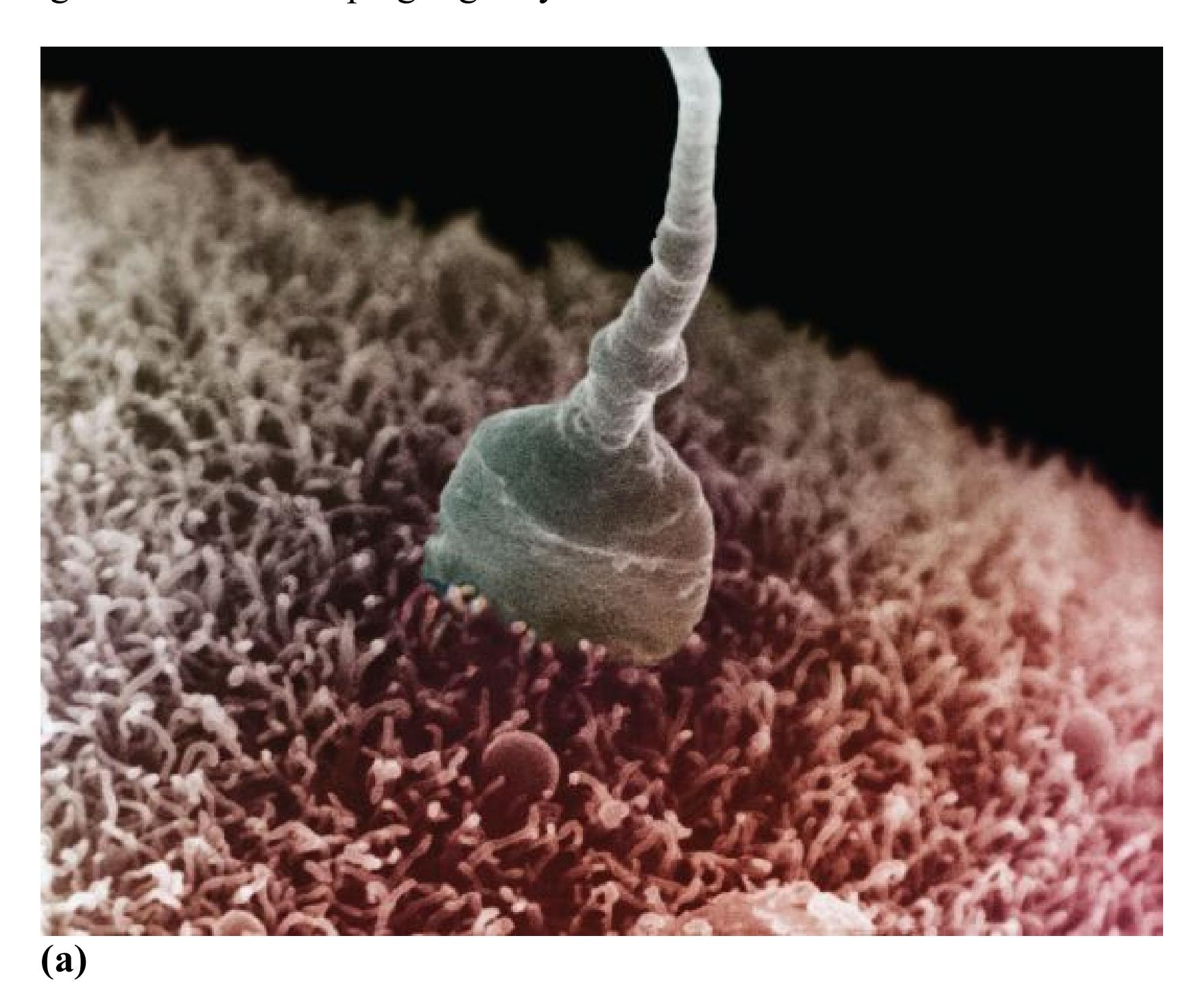

**GENETICS AND EPIGENETICS** The *human genome* is the basic *genetic code*, or blueprint, for the human body. For psychologists, this map represents the foundational knowledge for studying how specific genes—the basic units of hereditary transmission—affect thoughts, actions, feelings, and disorders. By identifying the genes involved in memory, for example, researchers might eventually be able to develop treatments, based on genetic manipulation, that will assist people who have memory problems.

Meanwhile, the scientific study of genetic influences has made clear that though nearly all aspects of human psychology and behavior have at least a small genetic component, very few single genes cause specific behaviors. Combinations of genes can predict certain psychological characteristics, but the pathways of these effects are mostly unknown. Adding to the complexity of this picture, a number of biological and environmental processes can influence how genes are expressed (for example, which genes get "turned on" and when) without changing the genetic code itself. [Epigenetics](#page-48-0) is the study of the ways these environmental mechanisms can get "under the skin," particularly in early life, to influence our mind and behavior.

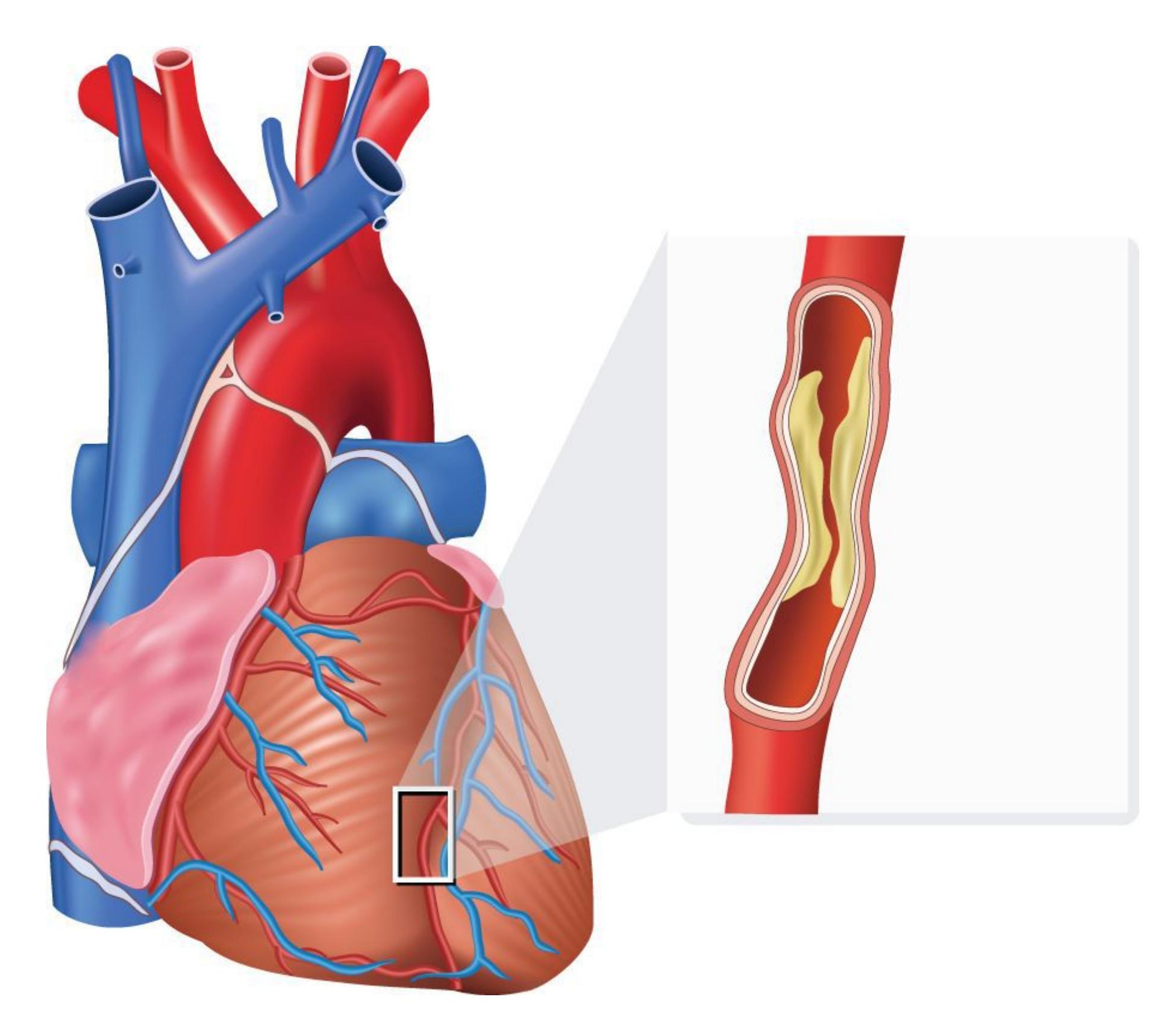

**IMMUNOLOGY AND OTHER PERIPHERAL SYSTEMS** Scientists have made enormous progress in understanding how the immune system protects our bodies and interacts with other systems that respond to stress, regulate our digestion, and metabolize energy. And all of these systems interact with brain function, structure, and development in fascinating ways. For psychologists, this knowledge reveals the deep and multilayered connections between our minds and other systems previously thought to be relatively independent. Some recent discoveries have transformed how psychologists conceive of stress, pain, and even depression (Alfven et al., 2019; Peirce & Alviña, 2019).

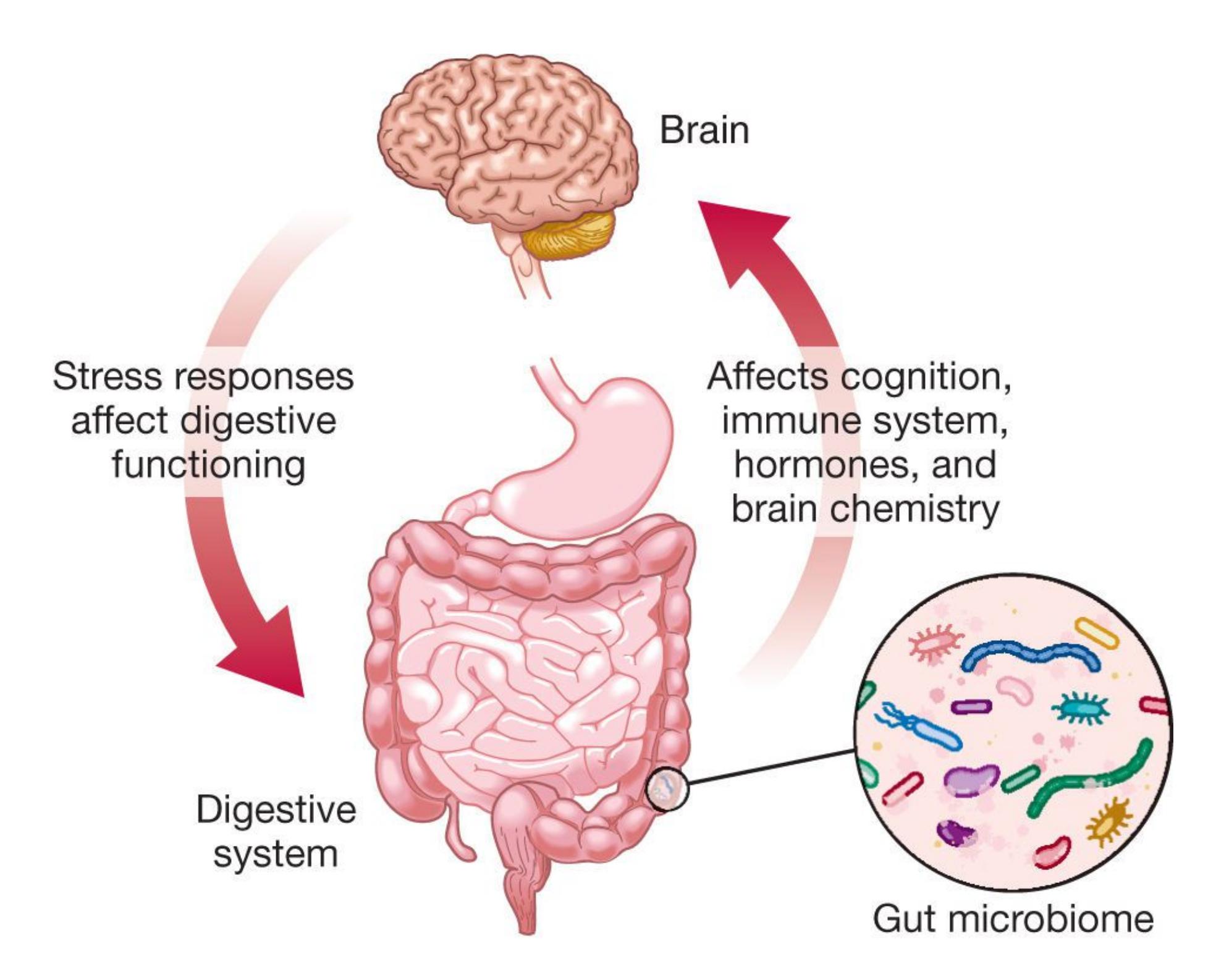

# FIGURE 1.14

# Gut-Brain Axis

Peripheral systems in the body, including the digestive system shown here, have two-way communication with the brain.

One particularly active area of research in psychology explores the two-way relation between the *gut microbiome*, the billions of microorganisms that live in our digestive tract, and our mind and behavior. Rapidly emerging science on the *gut-brain axis* reveals that the composition and diversity of these microorganisms can alter, and be altered by, the way our bodies respond to stress, mount an immune response, and direct attention (Foster et al., 2017; **FIGURE 1.14**). Through its complex interactions with the immune and metabolic systems, hormones, and neurotransmitters, the gut microbiome has a role in a variety of health conditions including irritable bowel syndrome, autism spectrum disorders, and anxiety.

Biological data can provide a unique window into understanding human psychology. But keep in mind that human psychology is the product of many factors beyond just biological ones. Our early experiences, our genes, our close relationships, our brains, and our cultures all contribute to who we are and what we do.

**What does brain imaging help psychologists study?**

**Answer:** localization of mental activity

## **Glossary**

# epigenetics

The study of biological or environmental influences on gene expression that are not part of inherited genes.

# 1.9 Psychology Is a Computational and Data Science

The widespread availability of very fast computers, low storage costs, and the internet connecting it all has transformed the way psychologists do their jobs. What began as a handy technological tool is now an integral part of the way psychologists gather, share, and analyze their data. Psychology is part of the "data science" revolution in at least three ways.

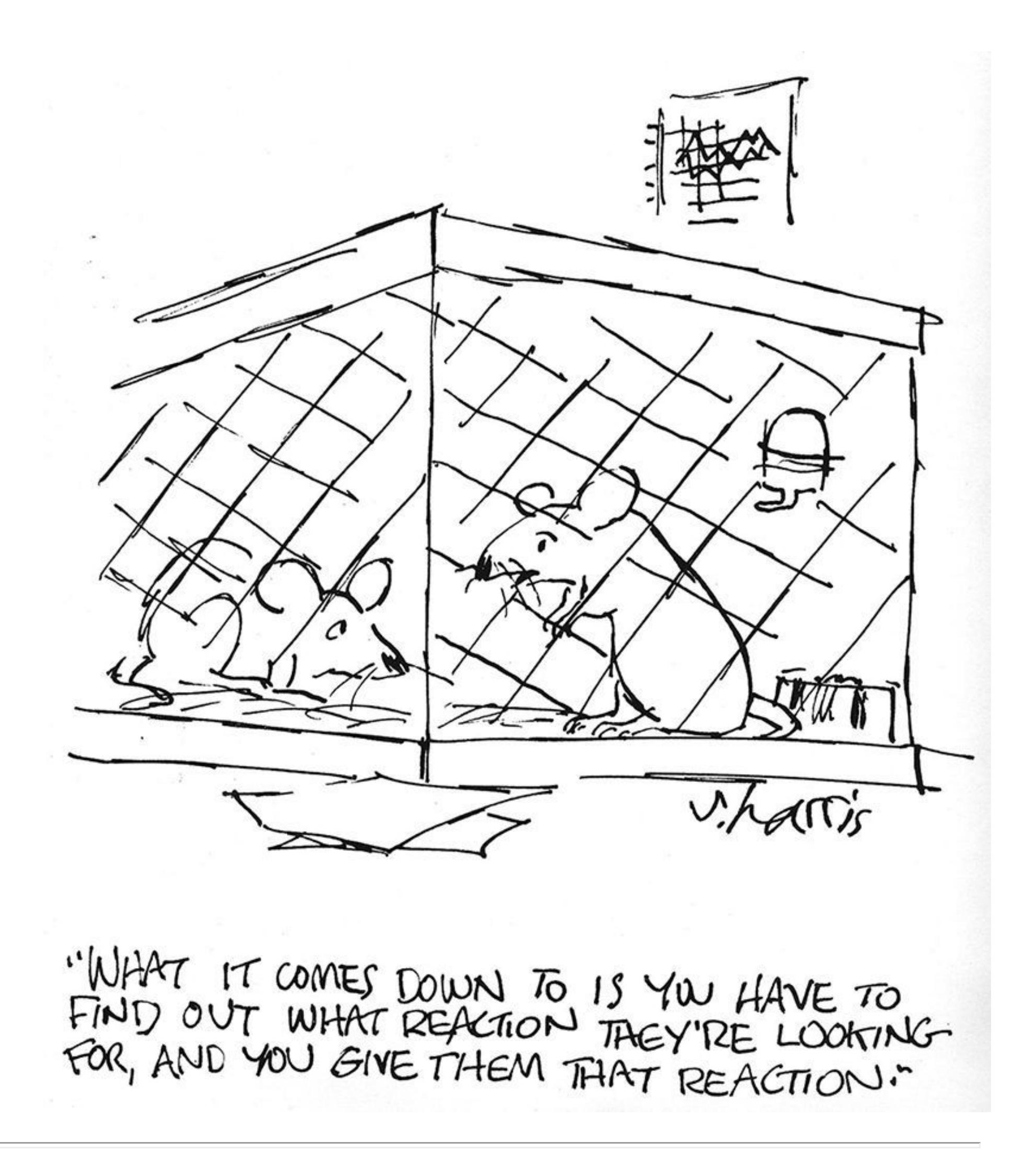

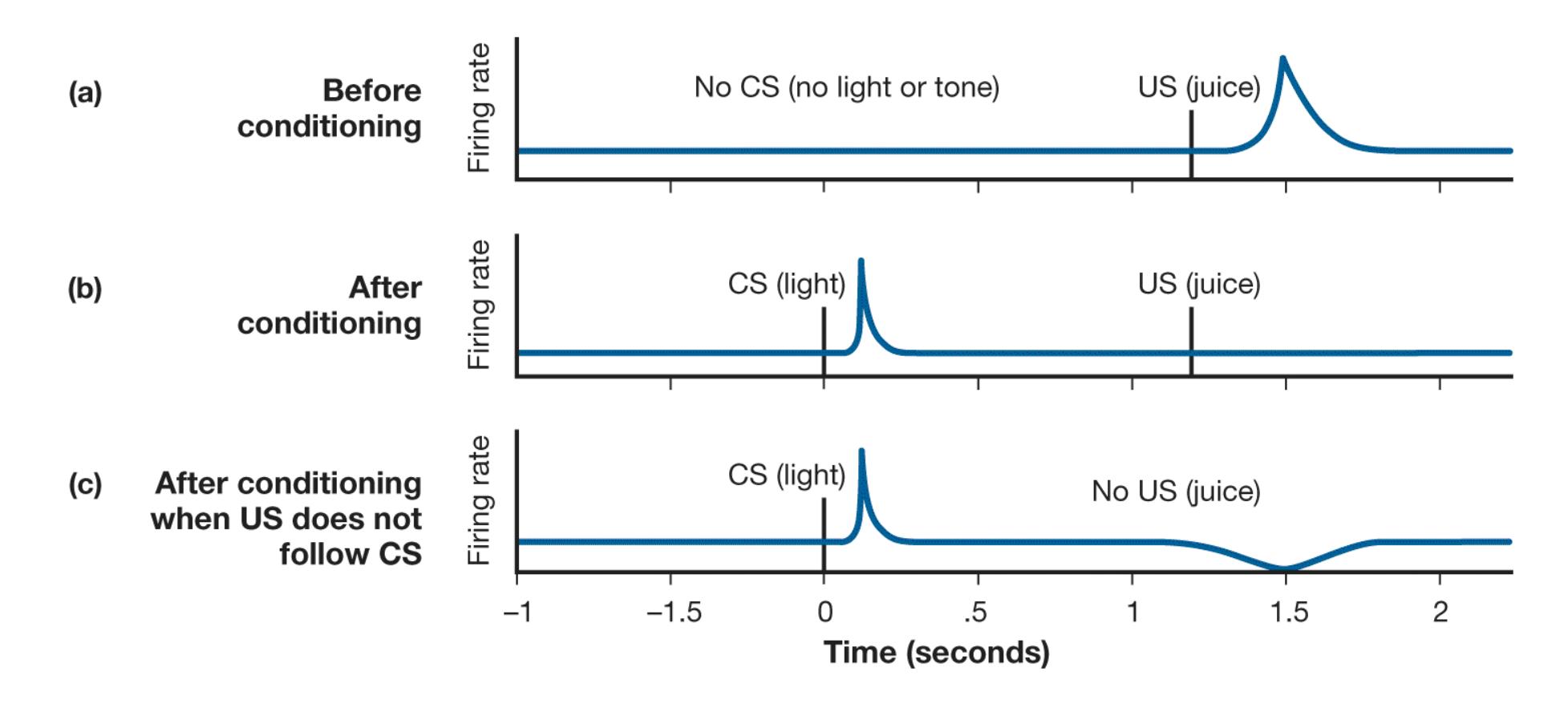

**COMPUTATIONAL MODELING** During the first half of the twentieth century, psychology was largely focused on studying observable behavior to the exclusion of mental events such as thoughts and feelings, an approach known as [behaviorism.](#page-54-0) Evidence slowly emerged, however, that learning is not as simple as the behaviorists believed it to be. Research across psychology in memory, language, and development showed that the simple laws of behaviorism could not explain, for example, why culture influences how people remember a story, why grammar develops systematically, and why children interpret the world in different ways during different stages of development. All of these findings suggested that psychologists would need to study people's mental functions and not just their overt actions to understand behavior.

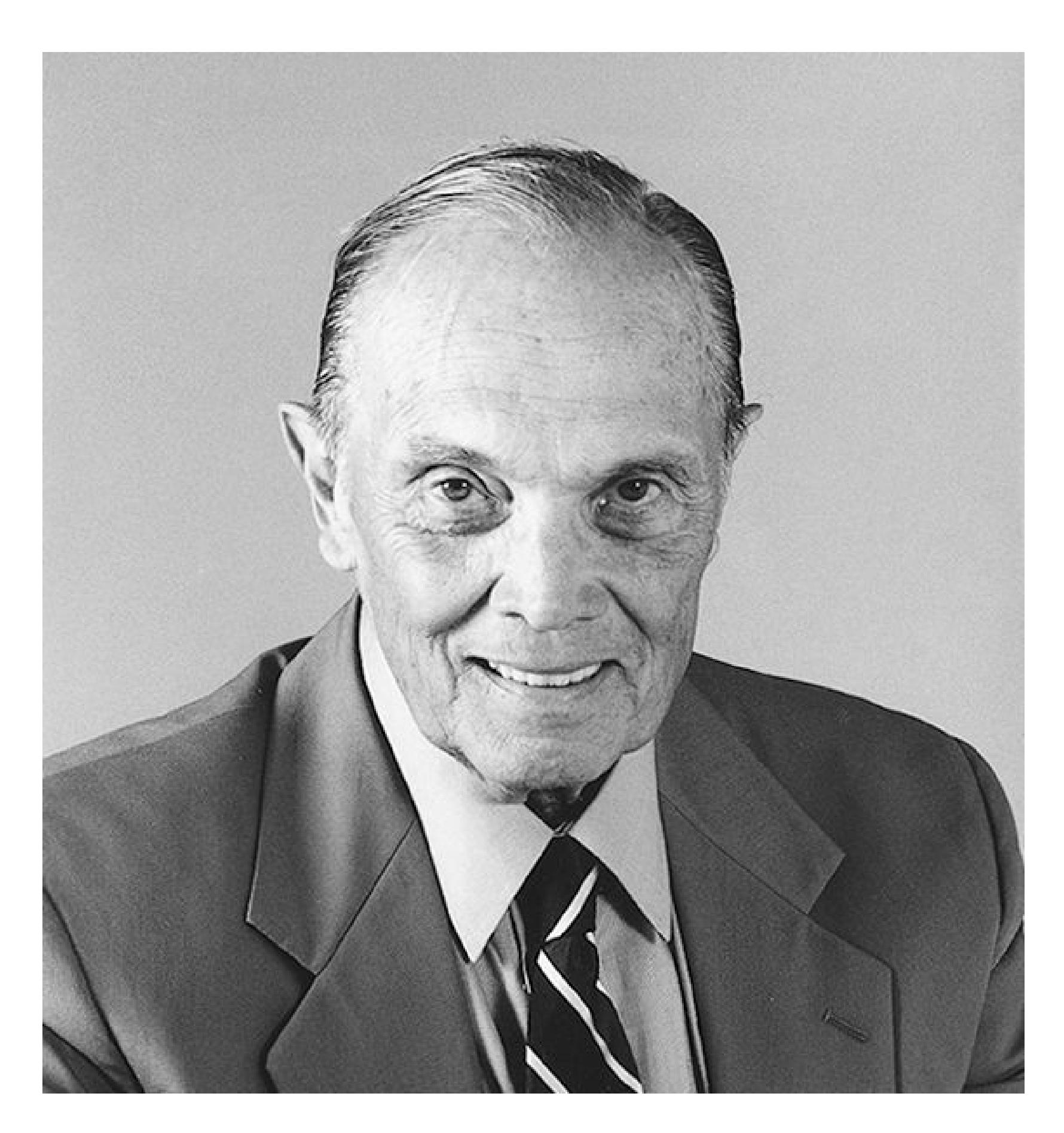

**FIGURE 1.15**

# George A. Miller

In 1957, Miller launched the cognitive revolution by establishing the Center for Cognitive Science at Harvard University.

To address this need, the psychologist George A. Miller and his colleagues launched the *cognitive revolution* in psychology (**FIGURE 1.15**) in the 1950s. In 1967, Ulric Neisser integrated a wide range of cognitive phenomena in his book *Cognitive Psychology*. This classic work named and defined the field and fully embraced the mind, which the behaviorist B. F. Skinner had argued was "fictional" (Skinner, 1974). (Radical behaviorism held that unobservable mental events are part of behavior, not its cause.)

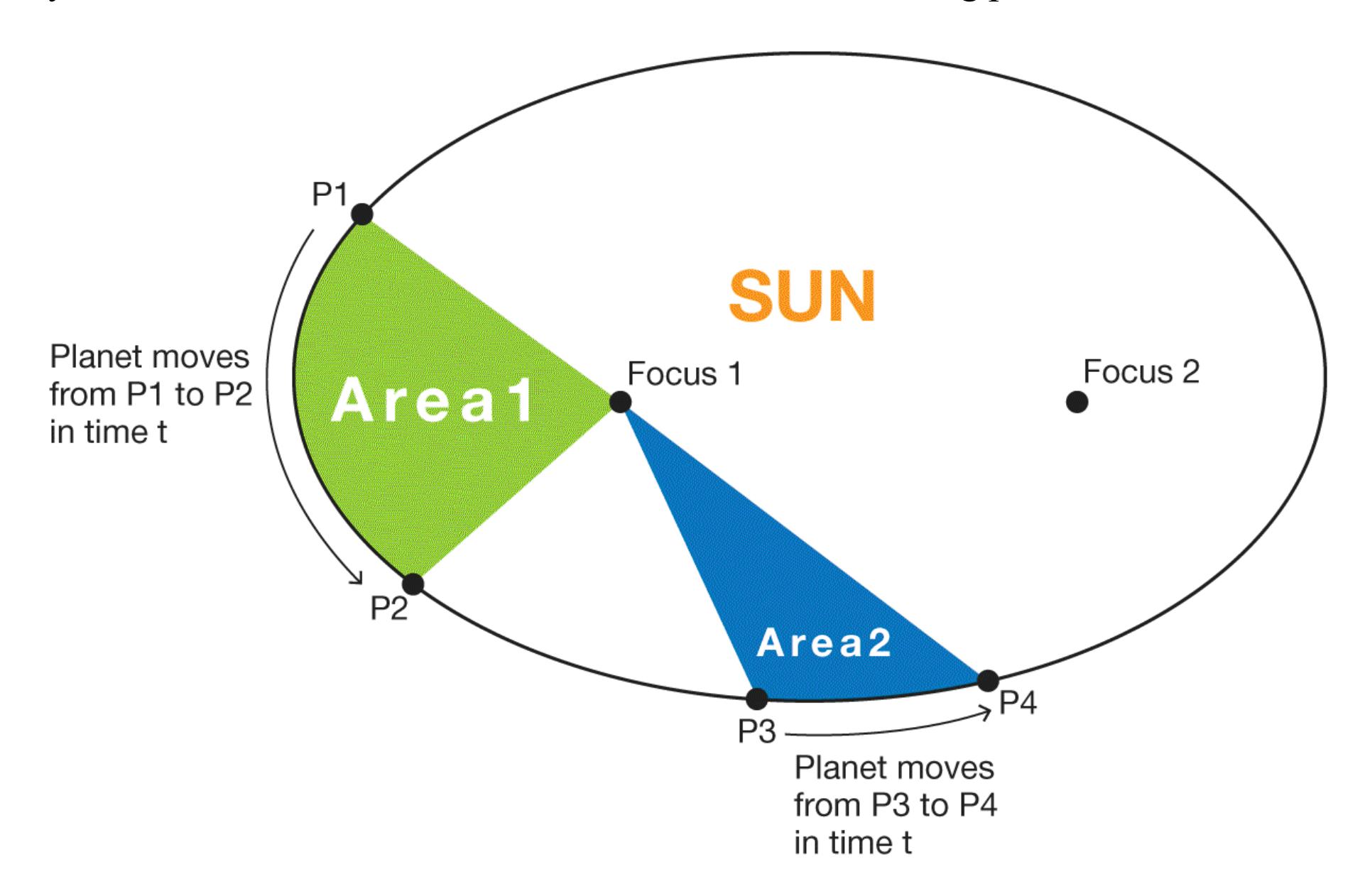

The cognitive revolution was accelerated by the computer age. Psychologists learned how to use simple computerized tasks to indirectly measure some components of cognition, including attention, working memory, inhibitory control, and reward learning. At first, the data extracted from these tasks were relatively simple measures such as reaction times and error rates. Now psychologists use computers to help build and test mathematical models of behavior that capture some of the important but invisible factors that underlie it. Just as mathematical models help physicists estimate the force of gravity using equations that describe the motion of the planets (**FIGURE 1.16**), computational models help psychologists understand processes such as a person's ability to learn about rewards. As these tools continue to develop, they will sharpen psychologists' ability to look inside the black box of the mind with increasing precision.

**FIGURE 1.16**

# Computational Modeling

Computers can solve mathematical models that describe the motion of the planets and the invisible properties of thought.

**BIG DATA** The computer that guided the *Apollo 11* flight to the moon in 1969 had about 72 kilobytes of memory, which is about enough memory for 0.2 seconds of a typical YouTube video. Zoom forward to today, when about 300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. The world is awash in data, and much of them are directly relevant to psychological questions. Psychologists are partnering with computer scientists to answer some of those questions using data available online from sources such as social media platforms, electronic medical records, and—yes —even YouTube.

The [big data](#page-54-1) approach uses tools from the computer science world, such as data mining and machine learning, to identify complex patterns in large data sets. These new methods have allowed psychologists to study topics such as ethnic discrimination in geographical regions based on Google searches, risk of alcoholism using specific combinations of genes or gene expressions, and personality profiles gleaned from activity on Twitter. The availability of very large data sets has also increased the diversity of the samples used in psychology research. At the same time, these methods are not without controversy. For instance, critics have questioned the ethics of using data that were originally collected for one purpose to answer different research questions. As big data moves forward, it is clear that the technology is advancing faster than our capacity to understand its implications. The related and equally important field of data [ethics grapples with issues of privacy, equal access to information, and how m](#page-54-2)uch we can control information about ourselves.

**REPLICABILITY, OPEN SCIENCE, AND DATA SHARING** One of the features of a good scientific study is [replicability,](#page-55-0) meaning that the results would be more or less the same if someone ran the study again. There is an unavoidable element of chance in psychological science because studies use small groups of people, or samples, to make inferences about larger groups of individuals. So, it is always possible that something about the particular sample or the details of how a study was run might cause a study not to replicate in a new sample. Psychologists have known about this possibility for a very long time and have taken measures to prevent it. Even so, a large-scale study by the Open Science Collaboration surprised the field in revealing that less than half of a sample of experiments in prominent psychology journals replicated (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). This and similar disturbing results prompted a movement to adopt reforms to increase the reliability of the results in the field.

**FIGURE 1.17**

# Open Science

Open science emphasizes research transparency and data accessibility. Psychologists have developed tools to help promote open science at all phases of the research process.

In the ensuing years, the field coalesced around an [open science movement](#page-55-1) to improve the methods used in psychological science by making research plans and designs more transparent, documenting failed studies, and sharing data among

researchers, among other steps (**FIGURE 1.17**). These steps have been adopted with enthusiasm by scientists in the field. The number of psychologists using best practices, such as writing down or publishing their research plans at the beginning of a study and allowing other people access to their data, has increased each year (Nosek & Lindsay, 2018). This textbook features studies that have replicated or would likely replicate based on the rigor of their methods. [Chapter 2](#page-83-0) describes some of the best practices for psychological research that emerged as part of the open science movement.

Among the benefits of the open science movement is a shift in norms about data sharing in psychology. It is now increasingly expected that researchers share original, anonymous data from experiments, and numerous internet platforms have sprung up to facilitate this access. These platforms host data from all areas of psychology, from lab experiments to developmental psychology studies to neuroimaging repositories. With some help from colleagues in computer science, psychological scientists are learning to combine data from these growing databases to conduct some of the most powerful and inclusive studies in the history of psychology.

# What is data ethics?

**Answer:** the branch of philosophy examining ethical questions around the collection, use, and sharing of human data

## **Glossary**

# behaviorism

A psychological approach that emphasizes environmental influences on observable behaviors.

# big data

Science that uses very large data sets and advanced computational methods to discover patterns that would be difficult to detect with smaller data sets.

# data ethics

The branch of philosophy that addresses ethical issues in data sciences, including data accessibility, identifiability, and autonomy.

# replicability

The likelihood that the results of a study would be very similar if it were run again.

# open science movement

A social movement among scientists to improve methods, increase research transparency, and promote data sharing.

# 1.10 Culture Provides Adaptive Solutions

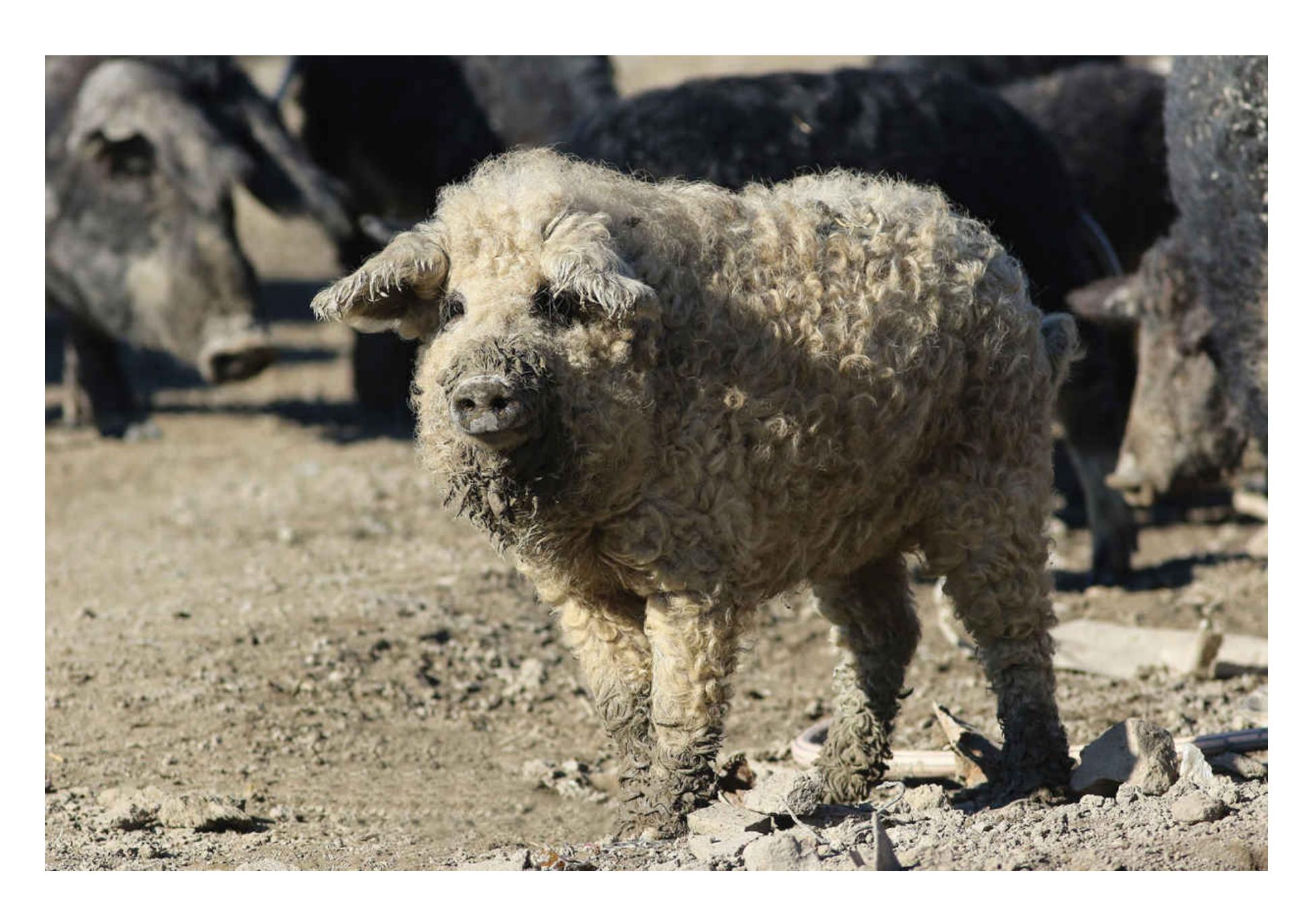

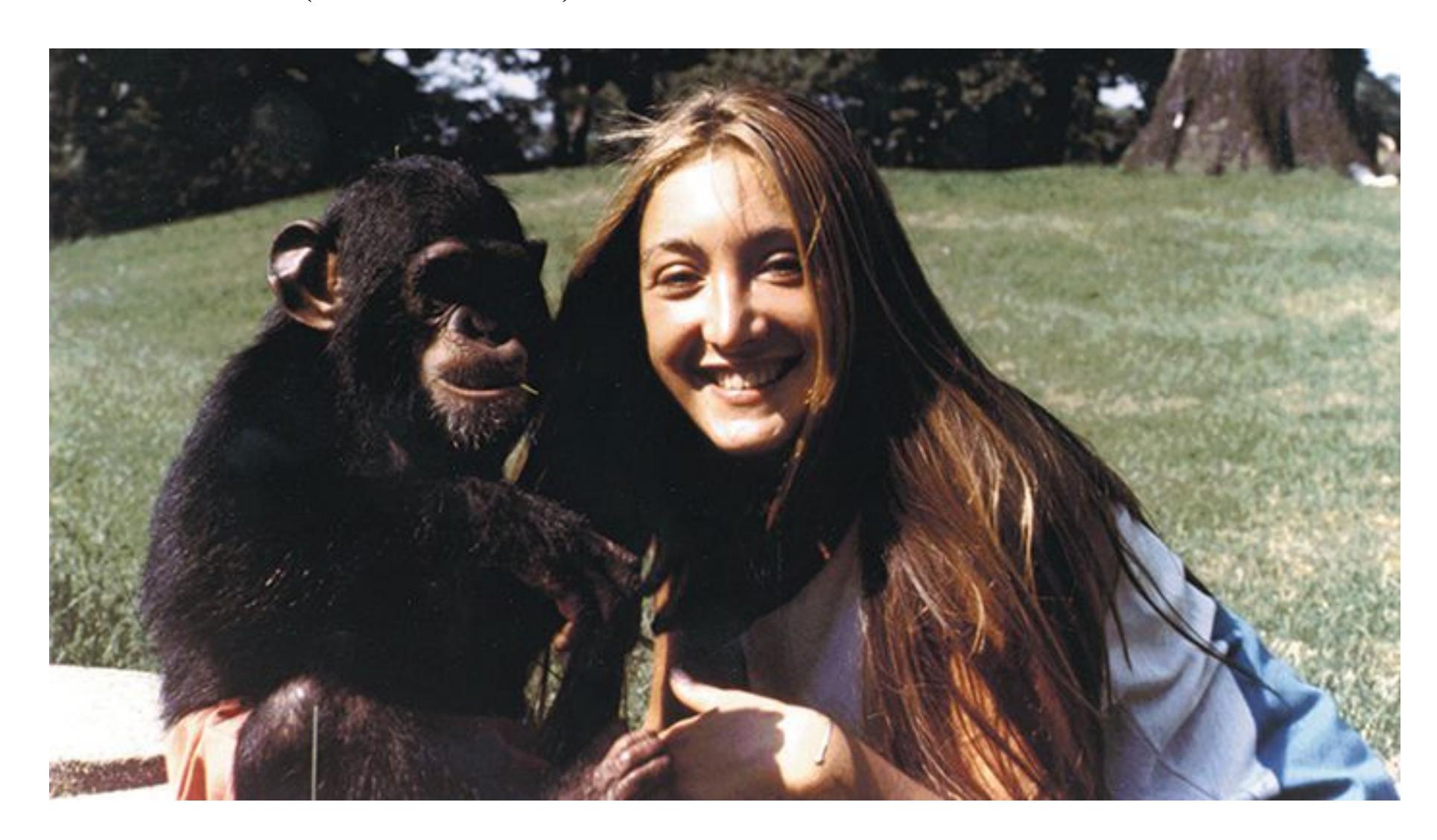

Through evolution, specialized mechanisms and adaptive behaviors have been built into our bodies and brains. For instance, a mechanism that produces calluses has evolved, protecting the skin from the abuses of physical labor.

Likewise, specialized circuits have evolved in the brain to address the most demanding adaptive challenges we face, many of which involve dealing with other people (Mills et al., 2014). These challenges include selecting mates, cooperating in hunting and in gathering, forming alliances, competing for scarce resources, and even warring with neighboring groups. This dependency on group living is not unique to humans, but the nature of interactions within and between groups is especially complex in human societies. The complexity of living in groups gives rise to culture, and culture's various aspects are transmitted from one generation to the next through learning. For instance, musical preferences, some food preferences, subtle ways of expressing emotion, and tolerance of body odors are affected by the culture one is raised in. Many of a culture's "rules" reflect adaptive solutions worked out by previous generations.

Human cultural evolution has occurred much faster than human biological evolution, and the most dramatic cultural changes have come in the past few thousand years. Although humans have changed only modestly in physical terms in that time, they have changed profoundly in regard to how they live together. Even within the past century, dramatic changes have occurred in how human societies interact. The flow of people, commodities, and financial instruments among all regions of the world, often referred to as *globalization*, has increased in velocity and scale in ways that were previously unimaginable. Even more recently, the internet has created a worldwide network of humans, essentially a new form of culture with its own rules, values, and customs.

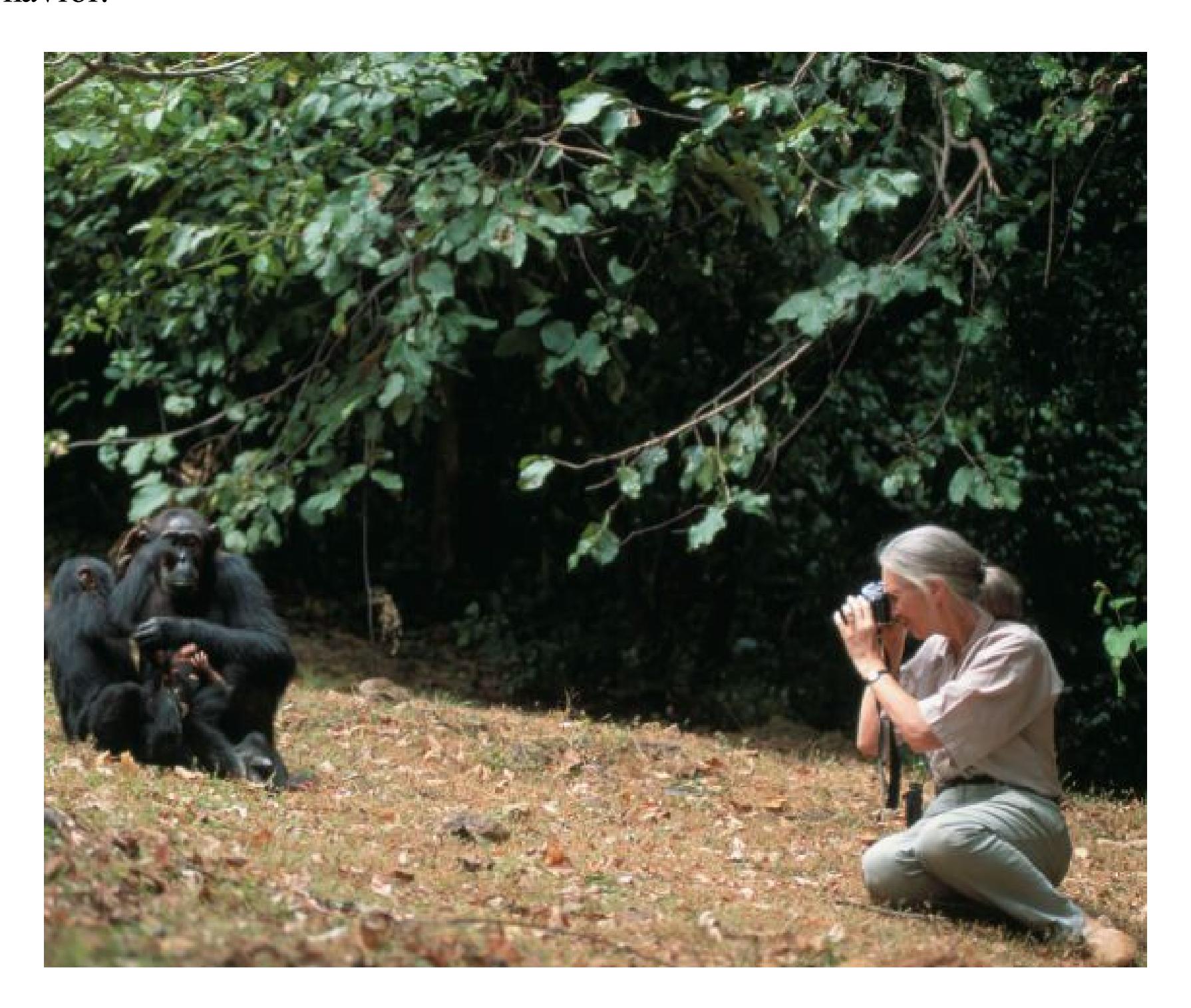

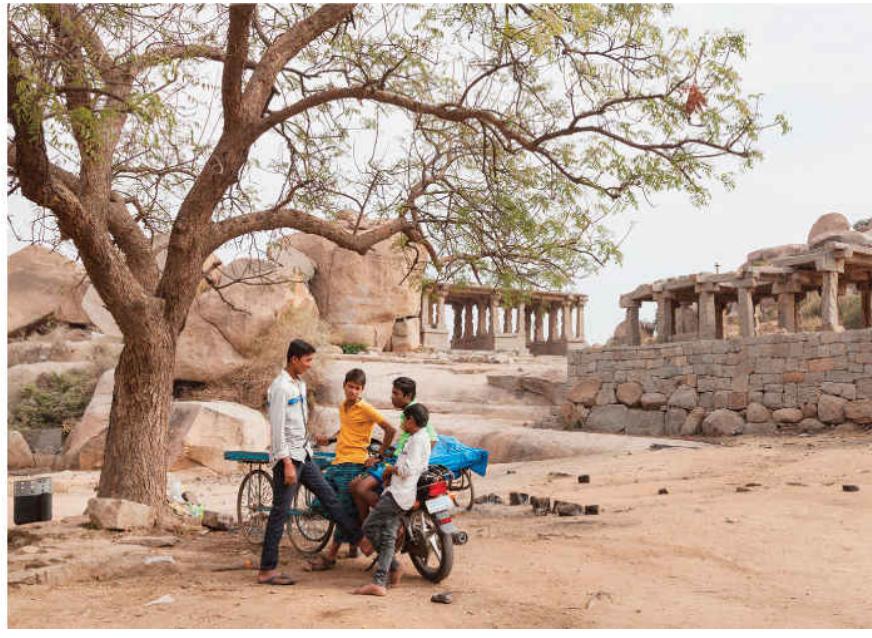

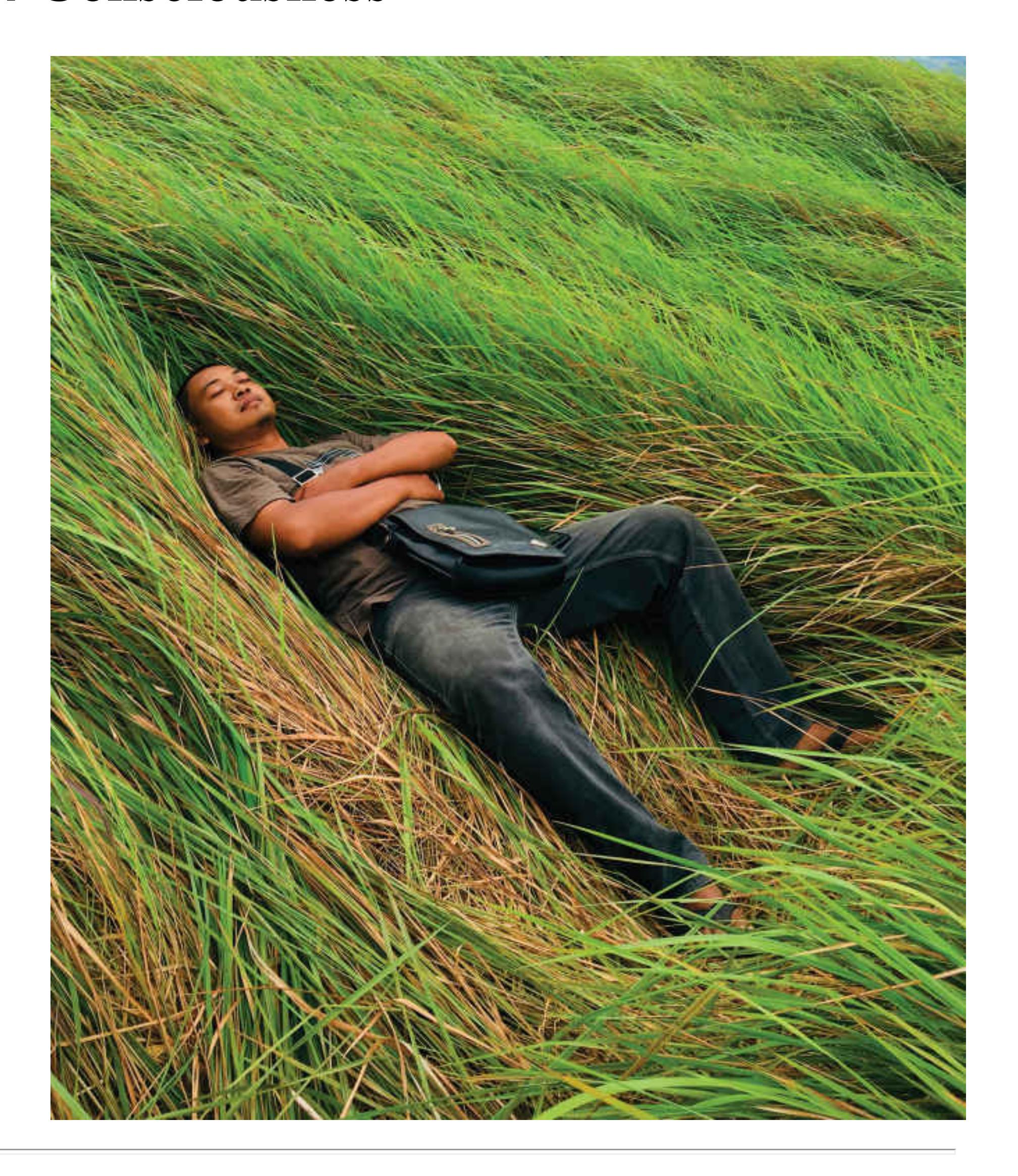

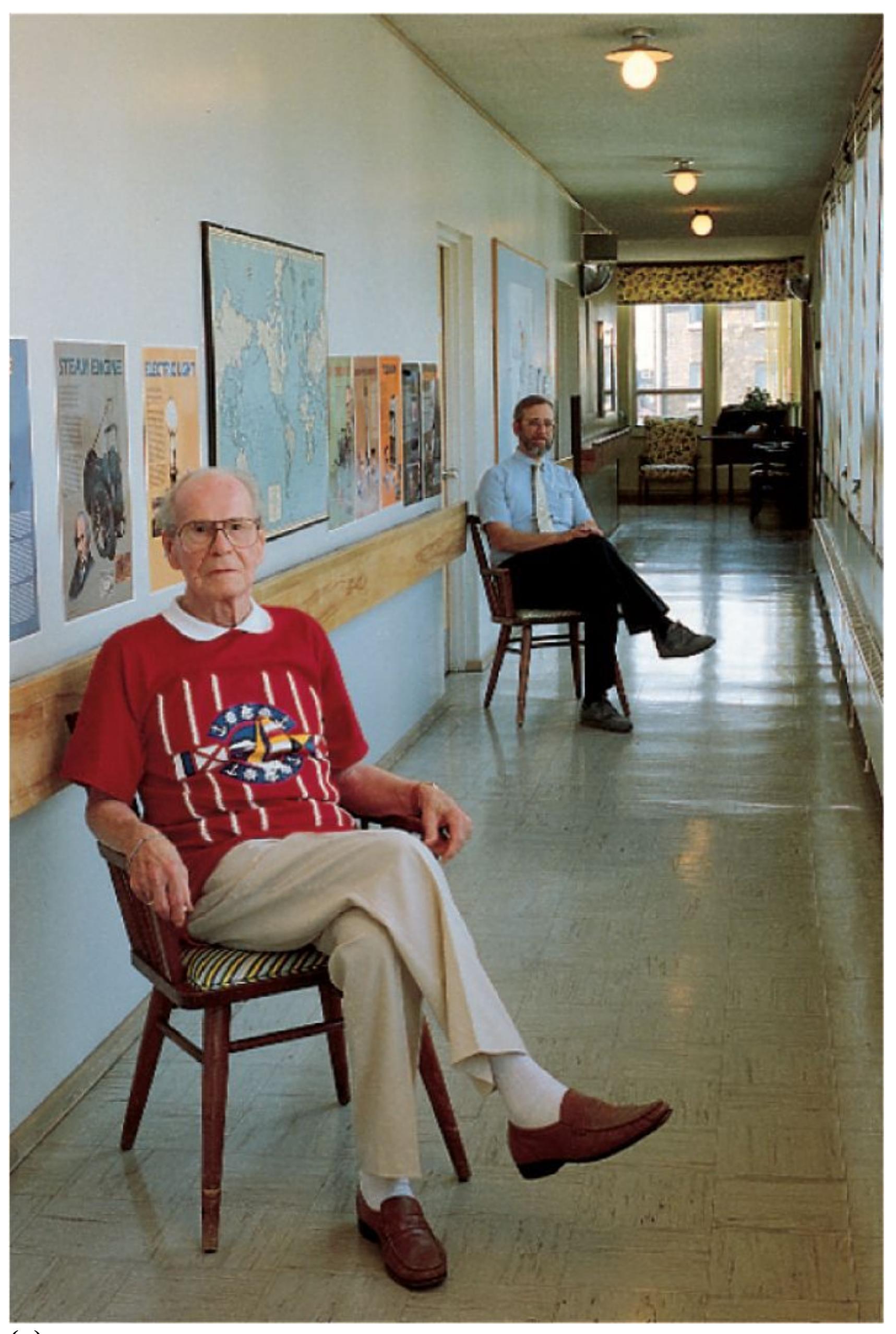

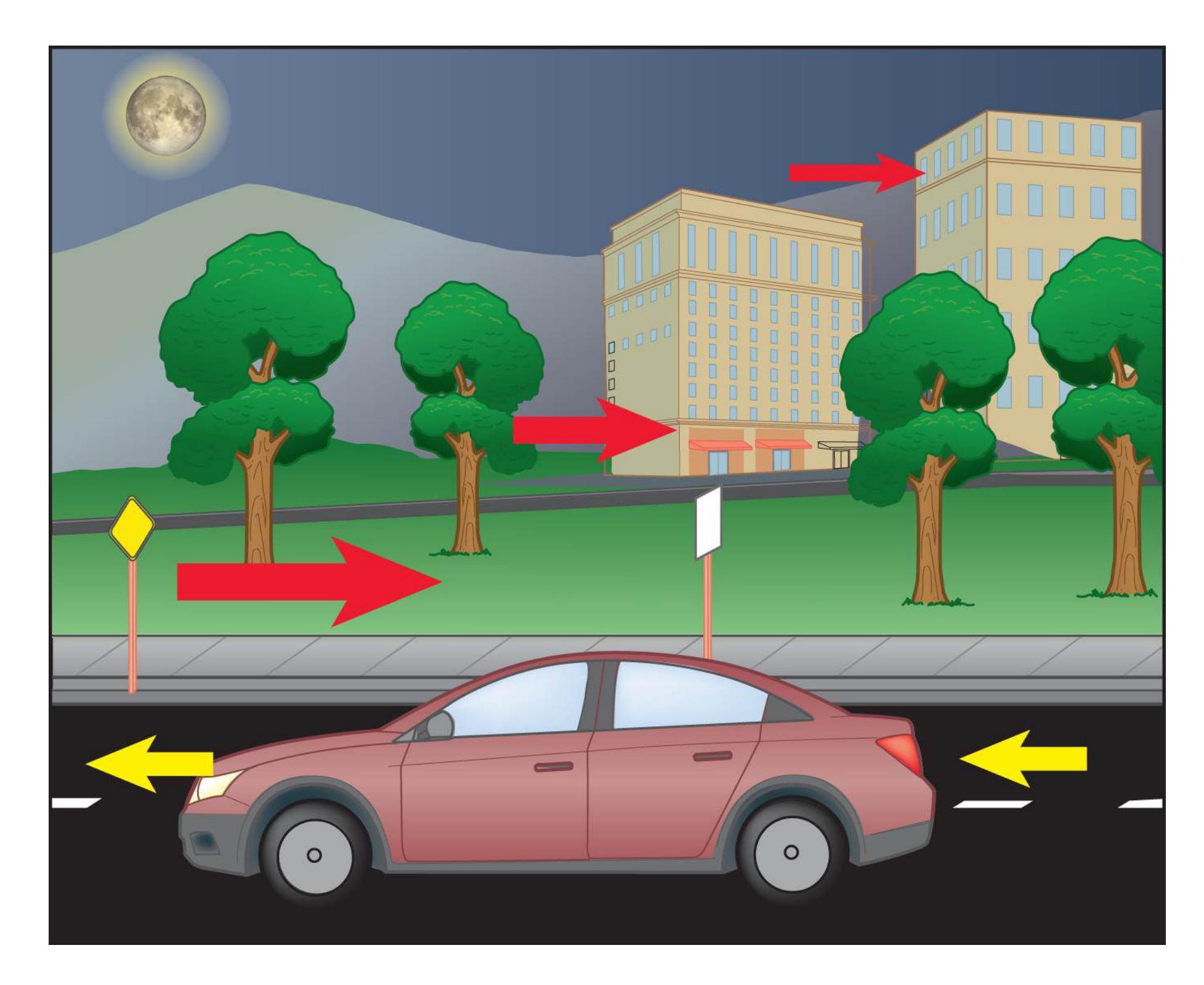

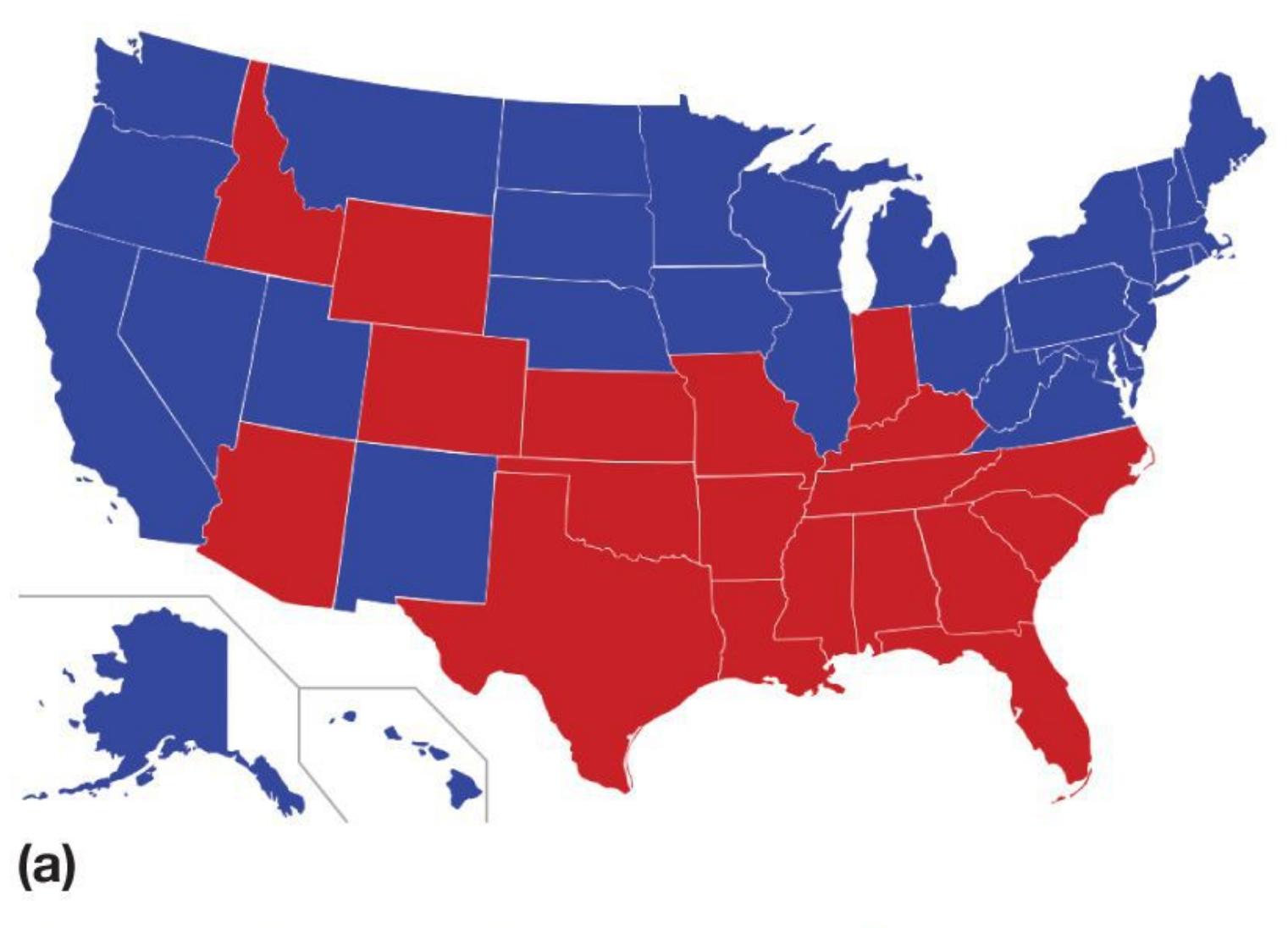

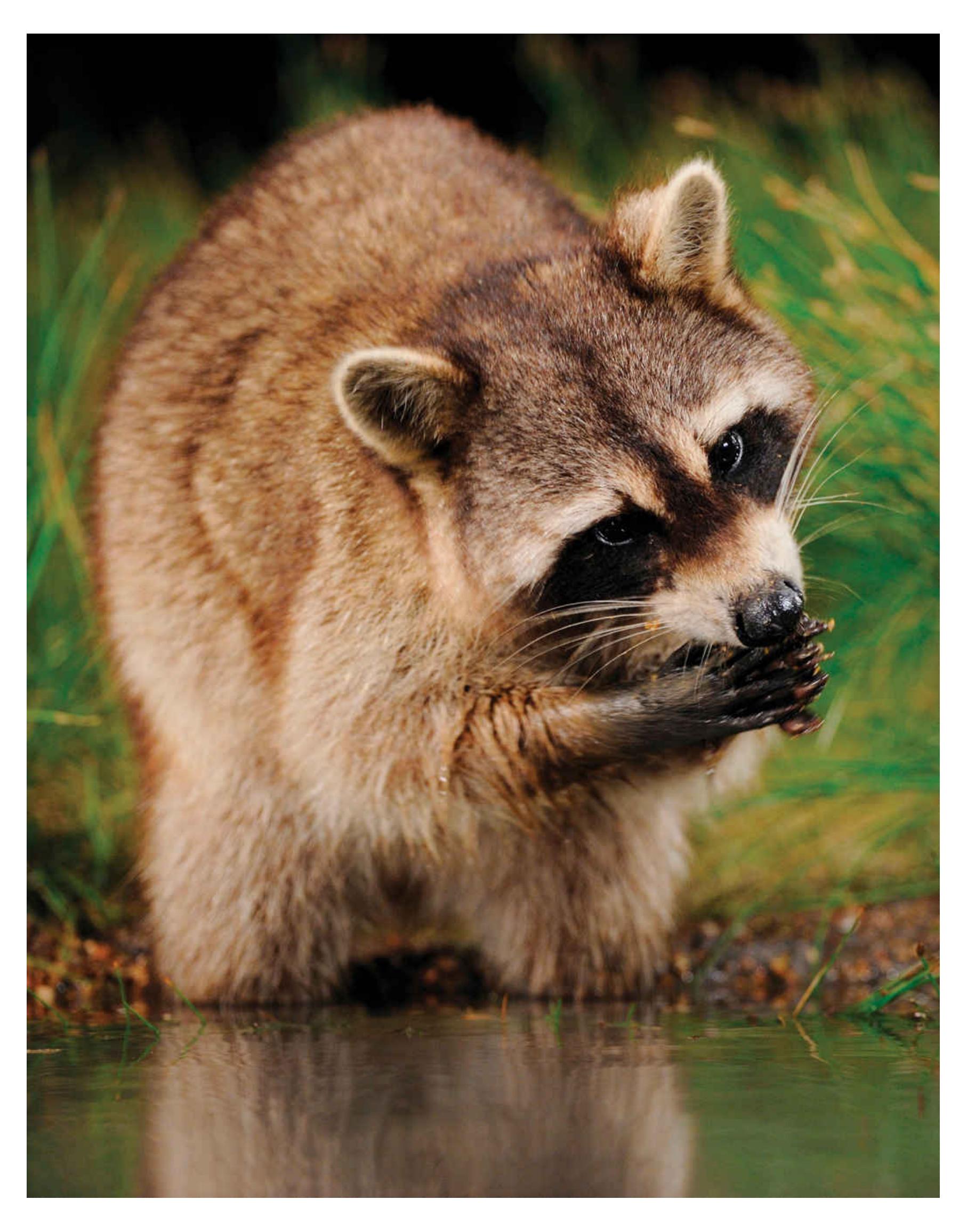

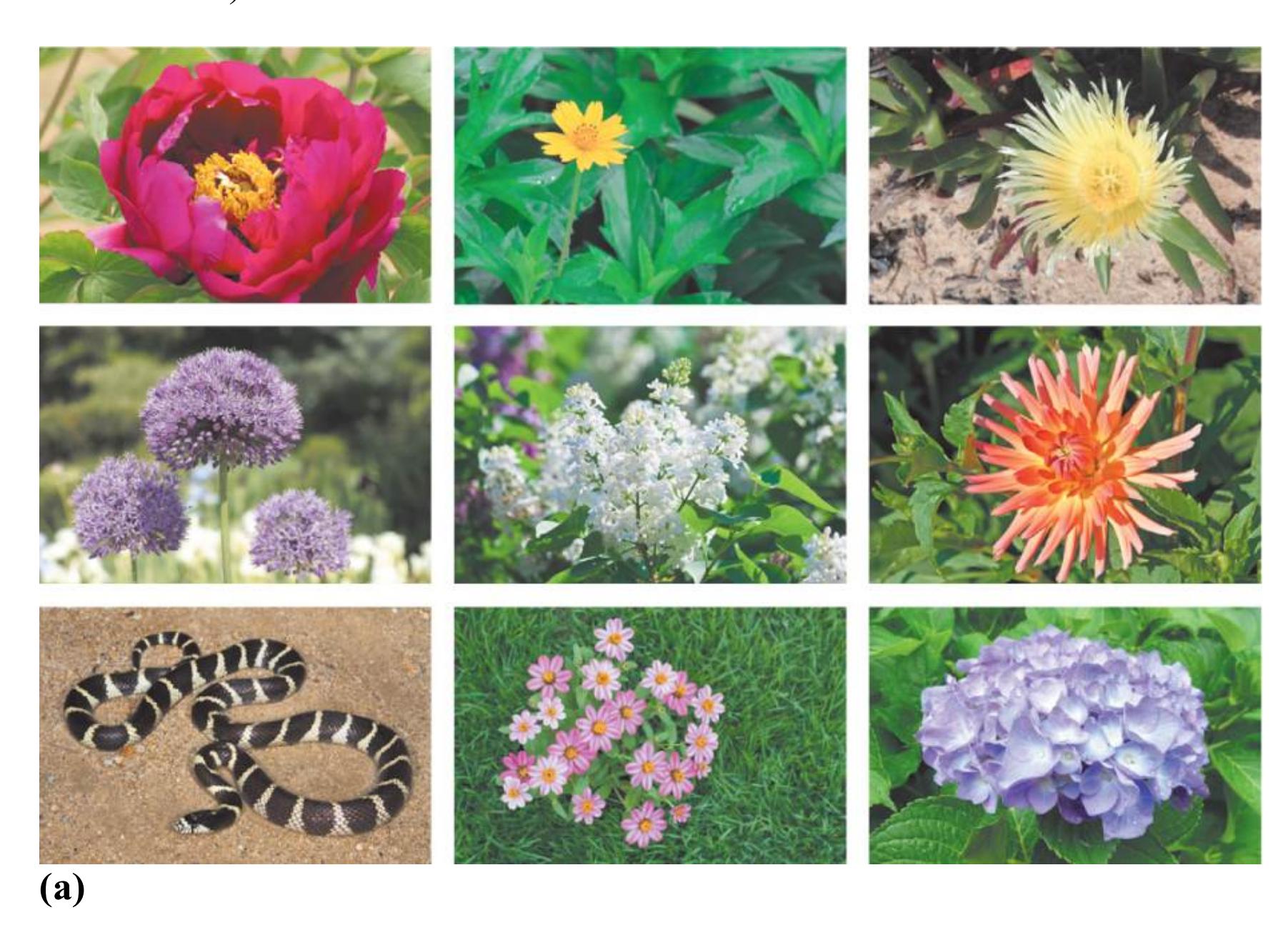

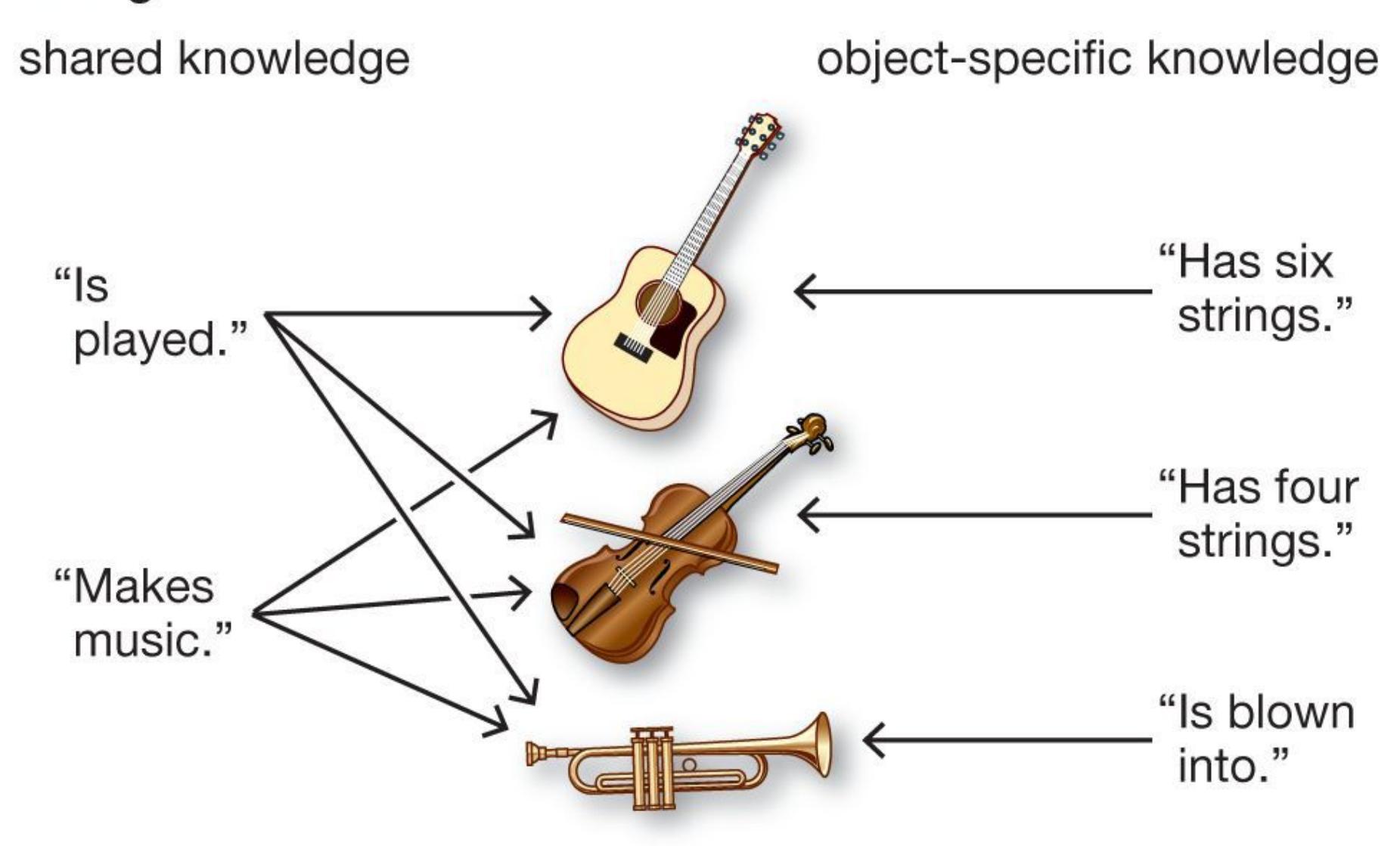

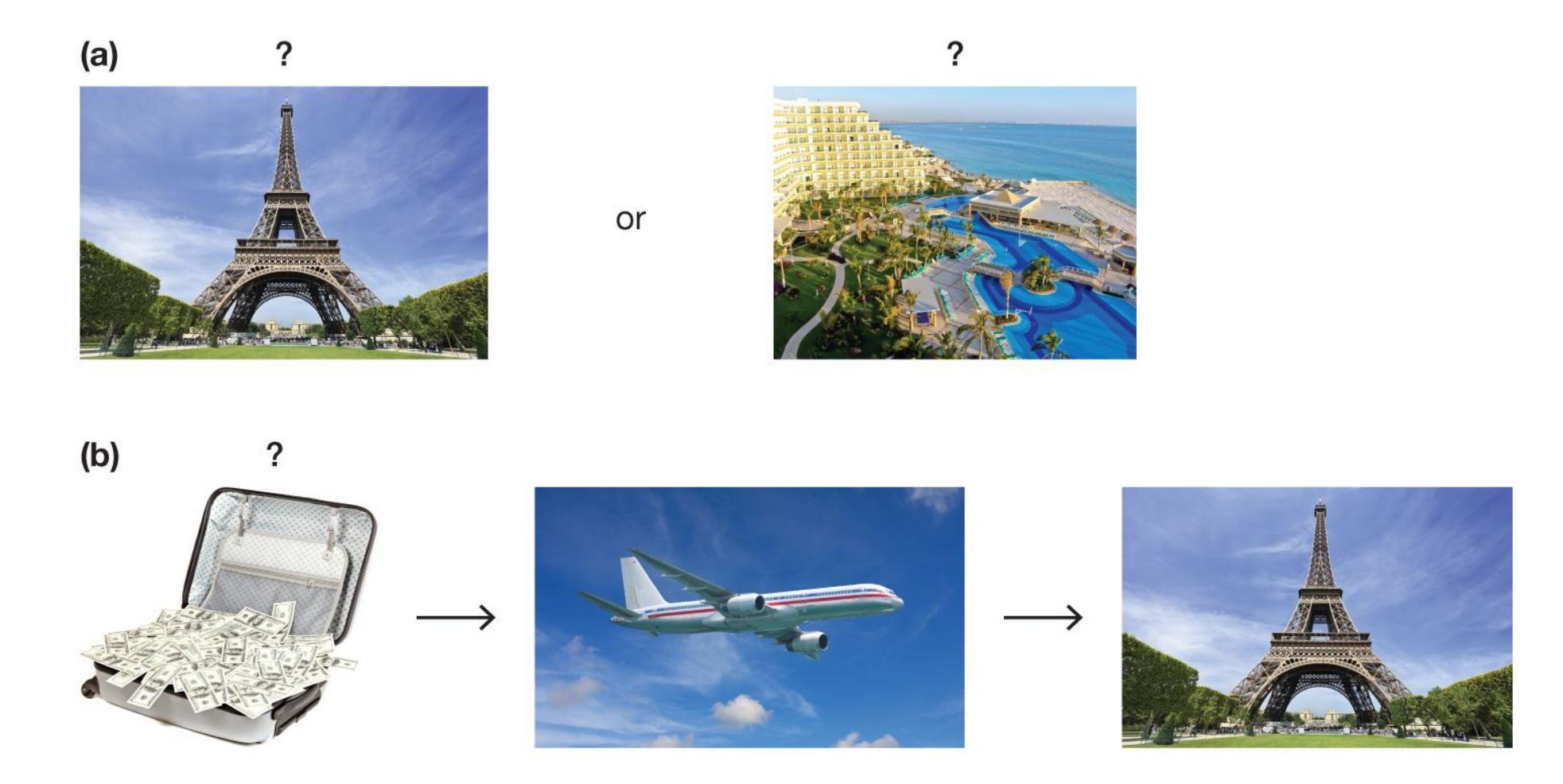

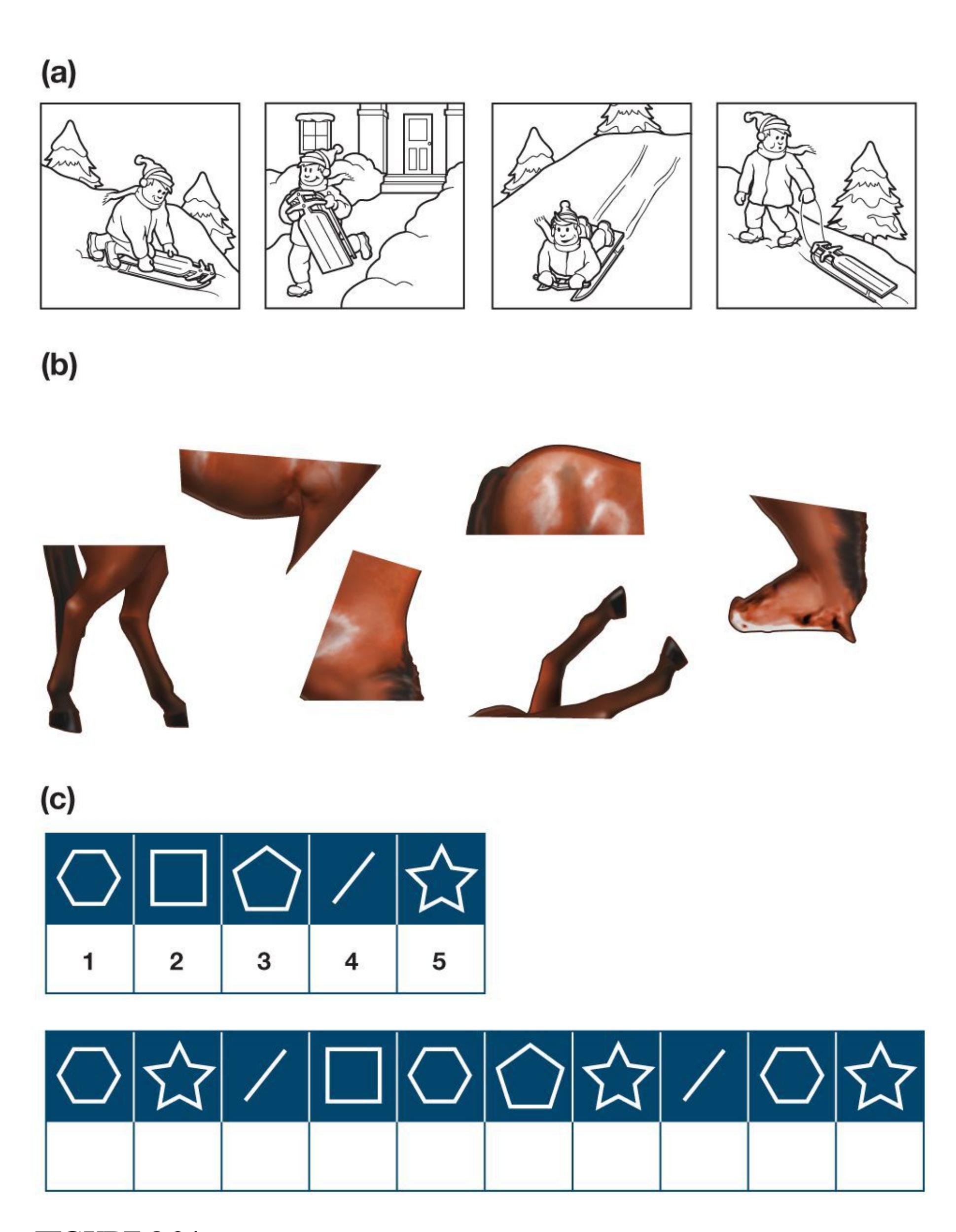

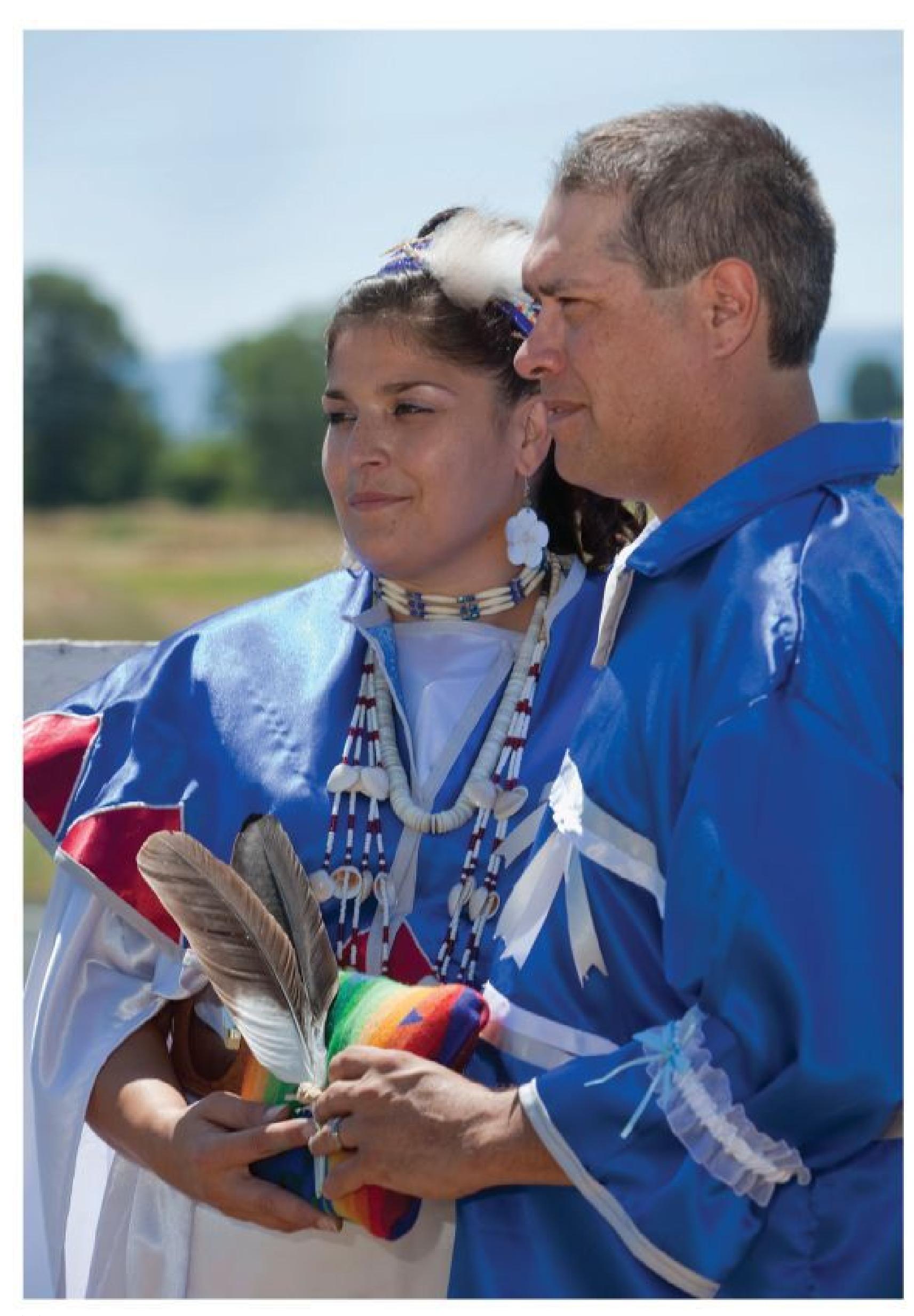

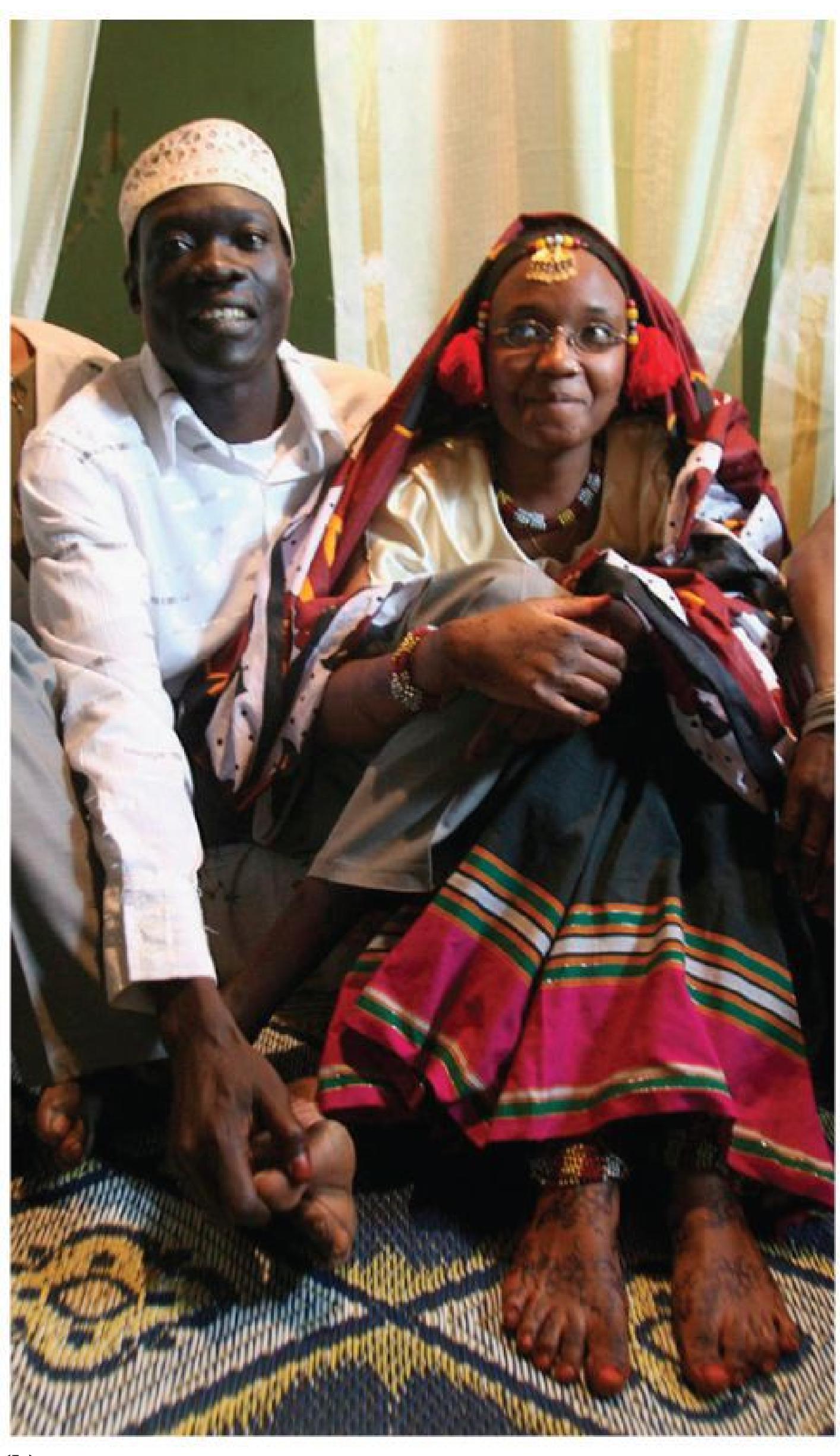

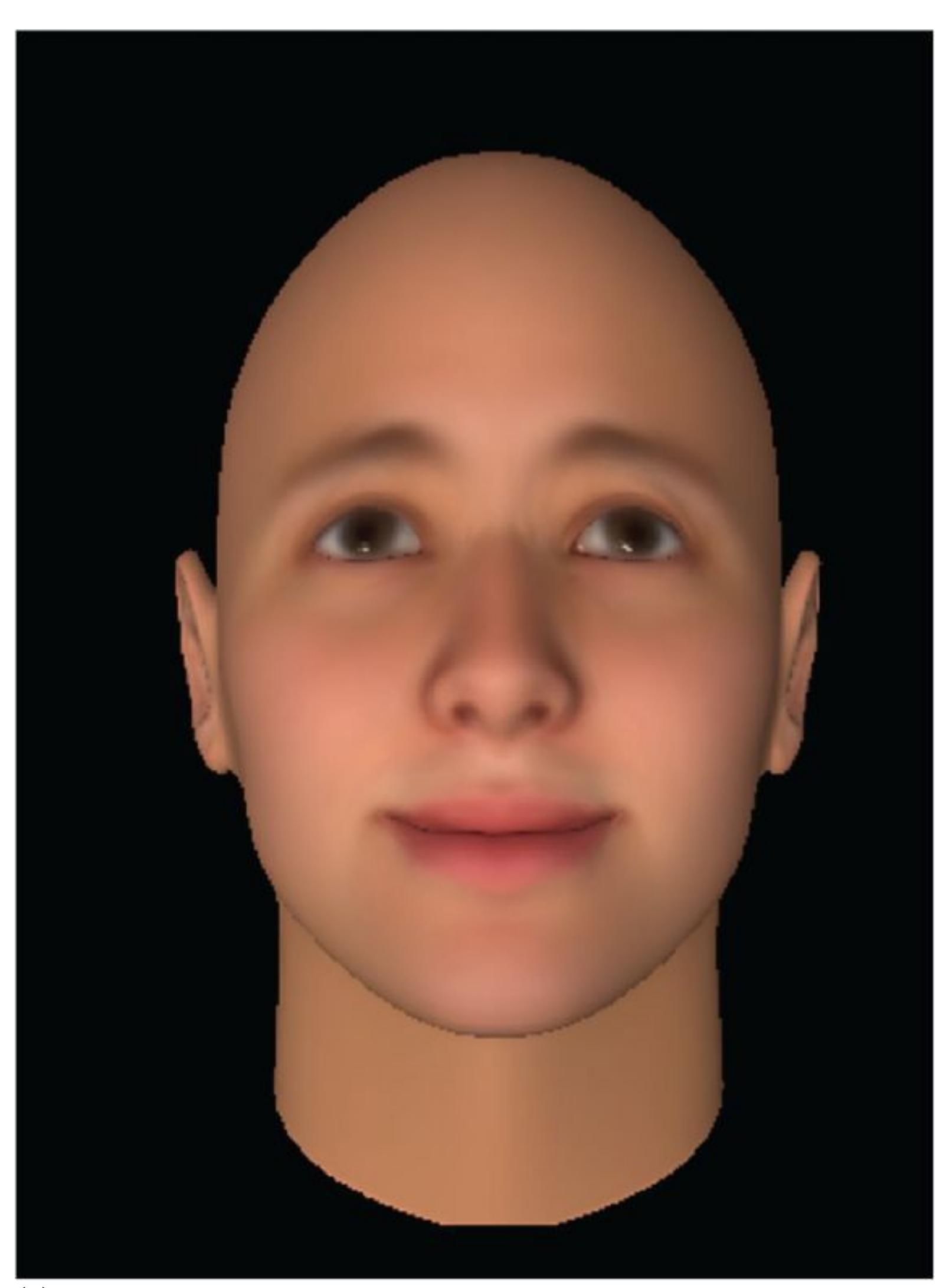

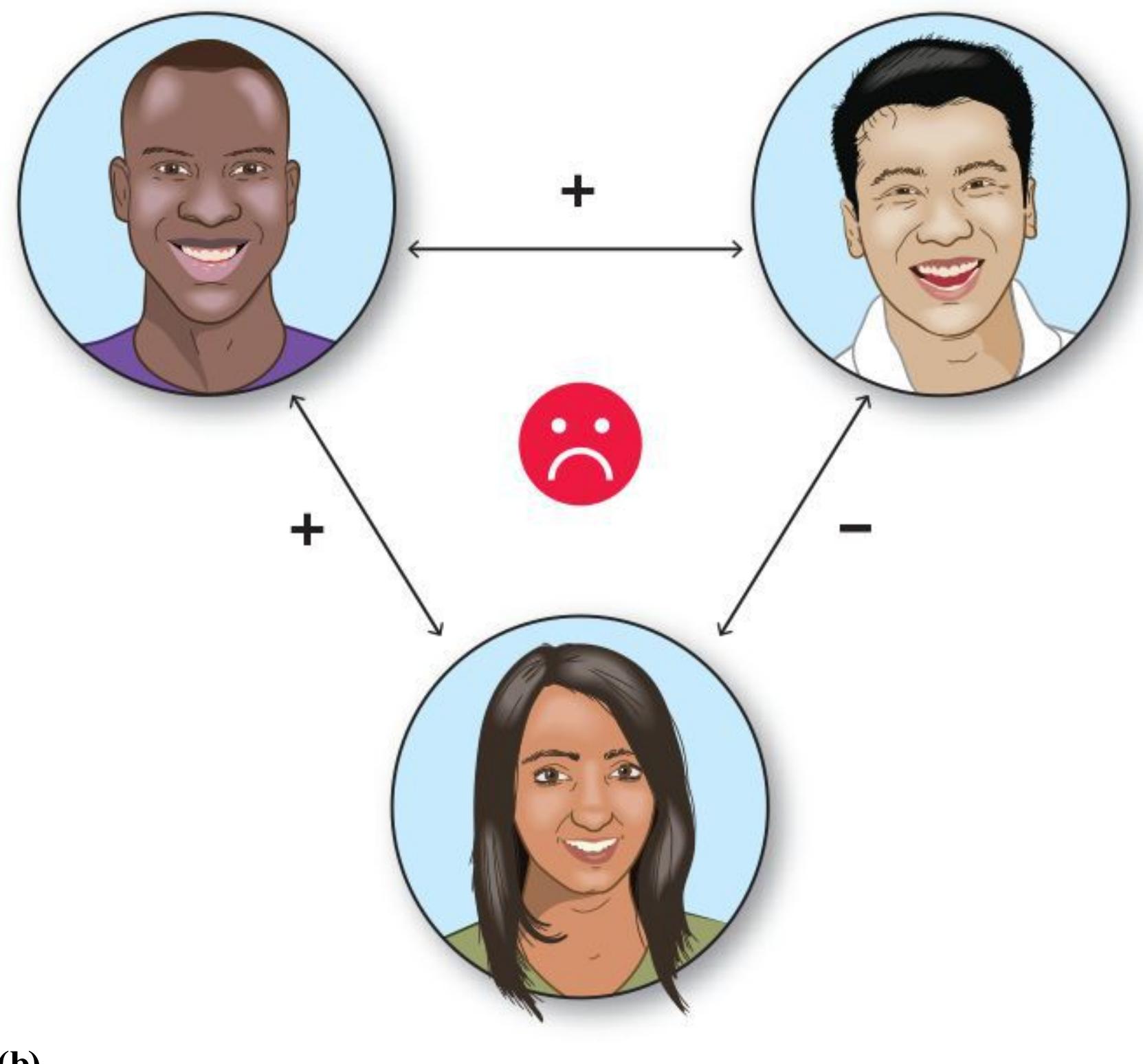

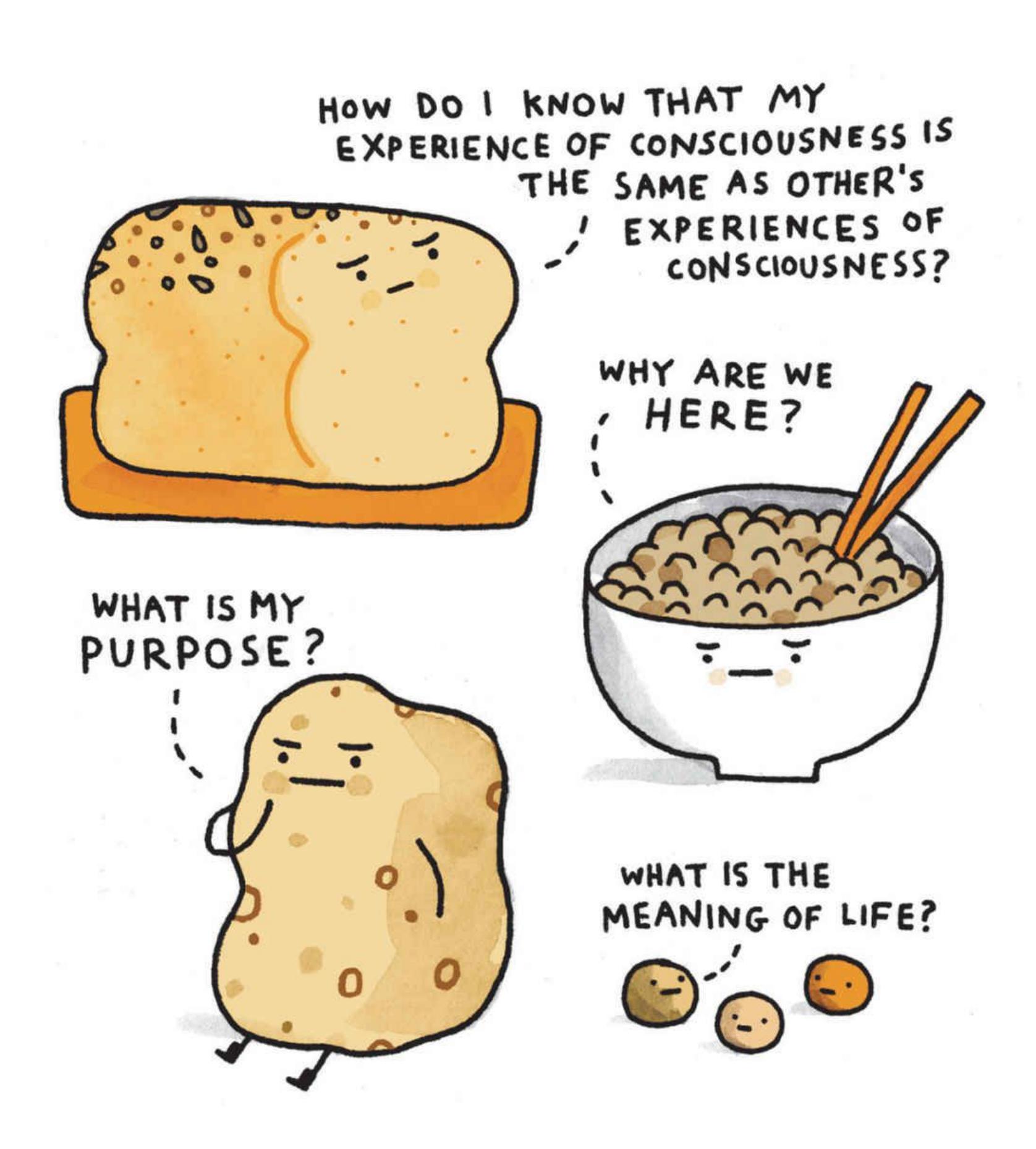

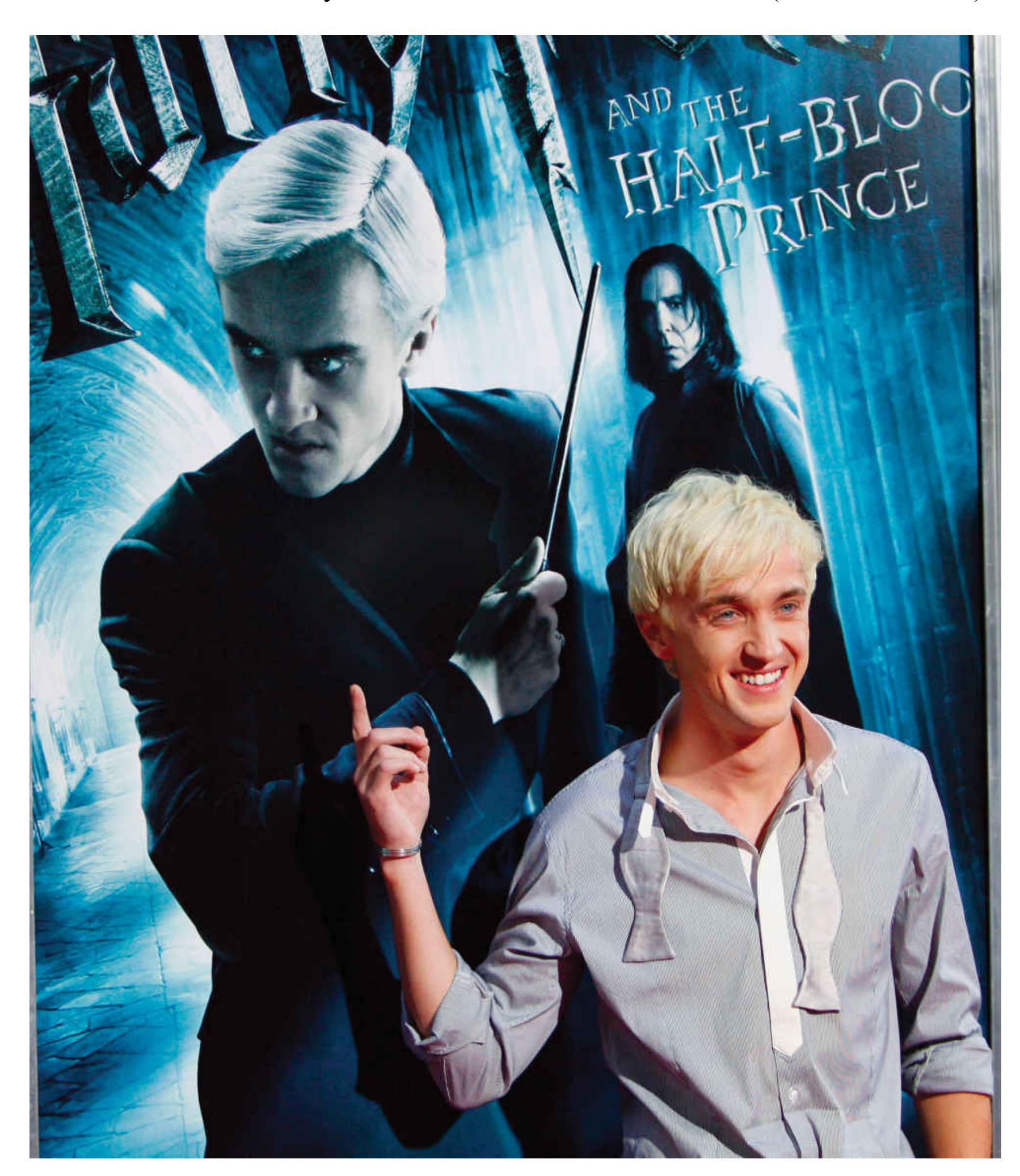

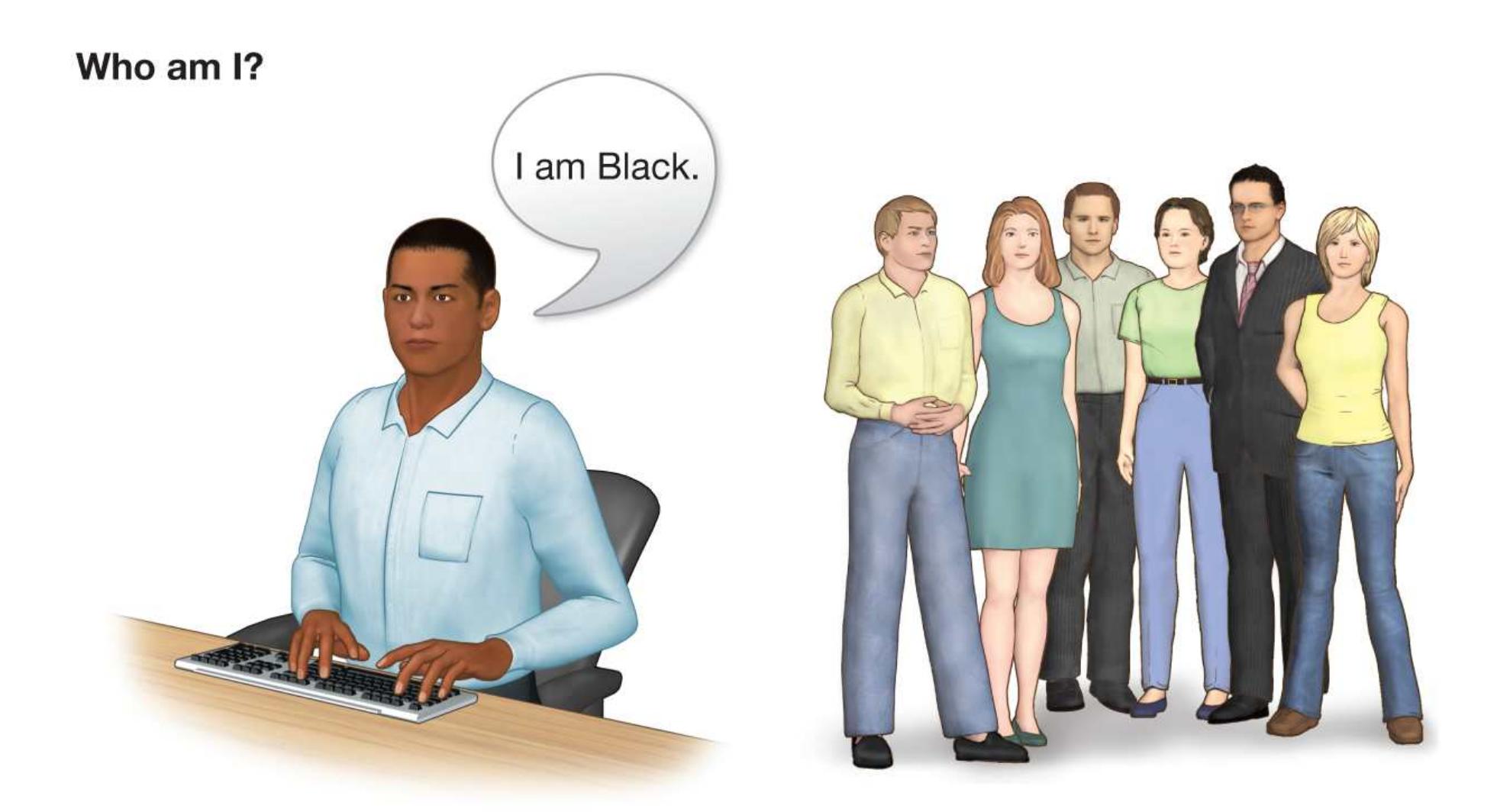

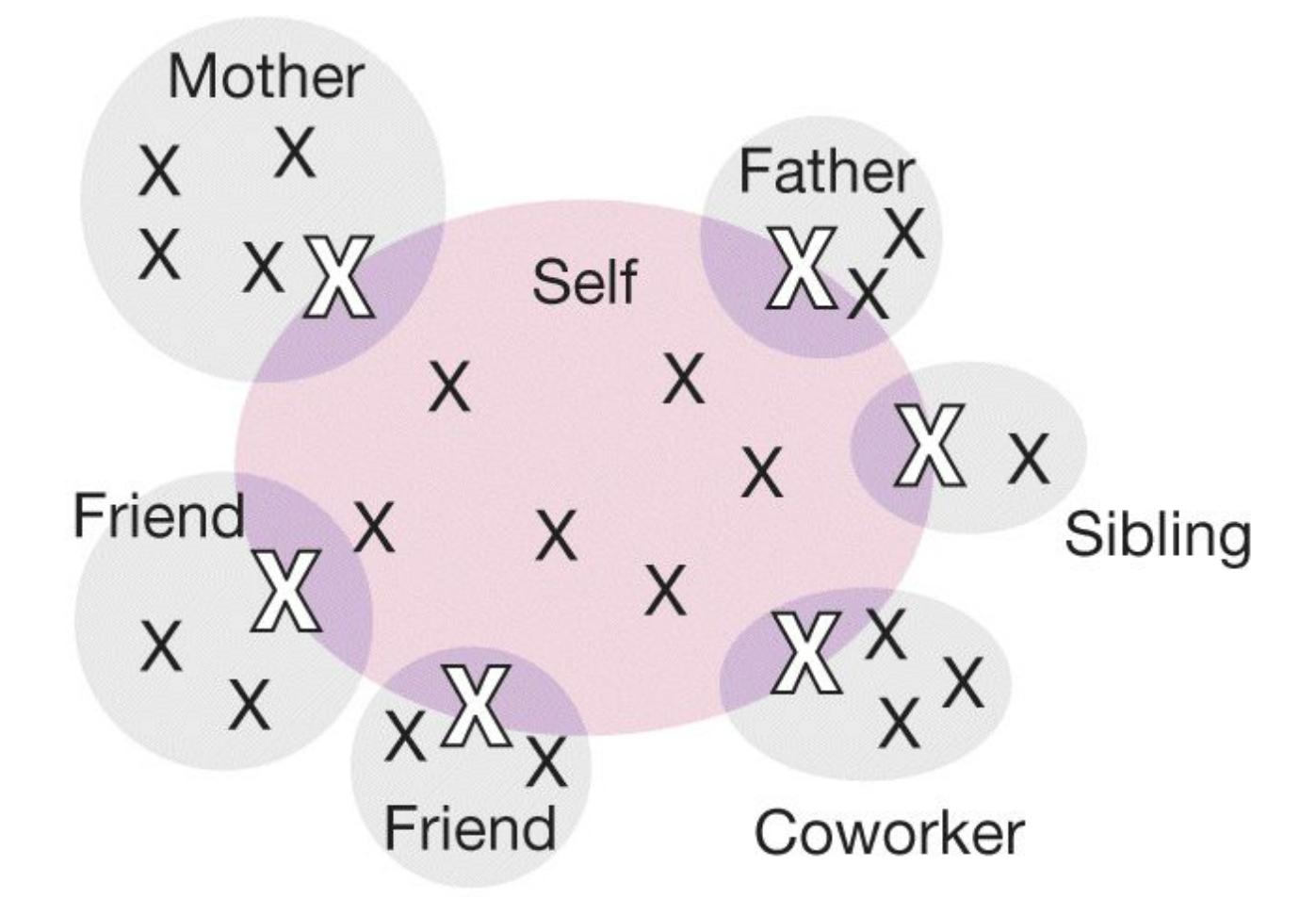

Over the past two decades, recognition has grown that culture plays a foundational role in shaping how people view and reason about the world around them—and that people from different cultures possess strikingly different minds (Heine, 2015). For example, the social psychologist Richard Nisbett and his colleagues (2001) have demonstrated that people from most European and North American countries are much more analytical than people from most Asian countries. Westerners break complex ideas into simpler components, categorize information, and use logic and rules to explain behavior. Easterners tend to be more holistic in their thinking, seeing everything in front of them as an inherently complicated whole, with all elements affecting all other elements (**FIGURE 1.18**).

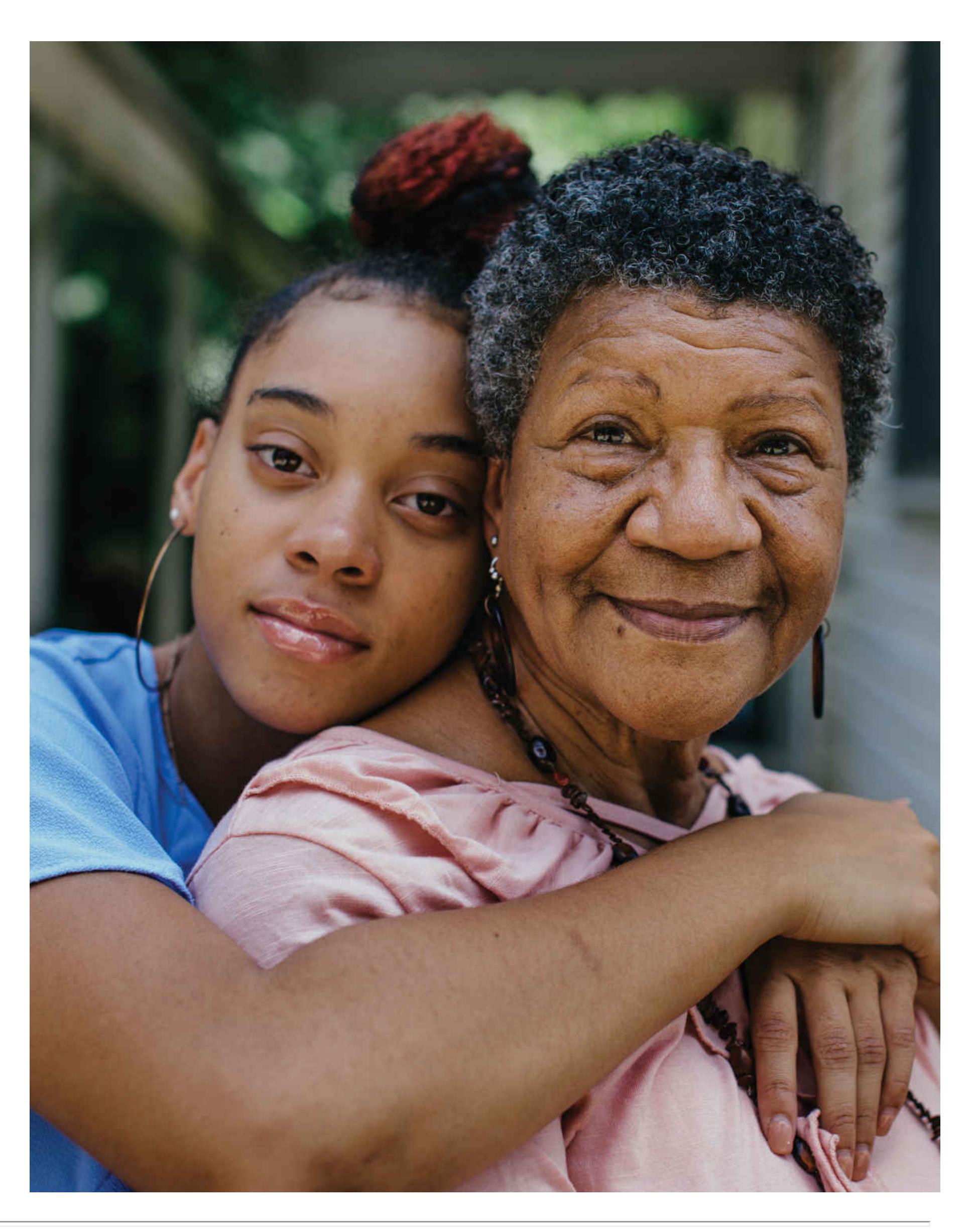

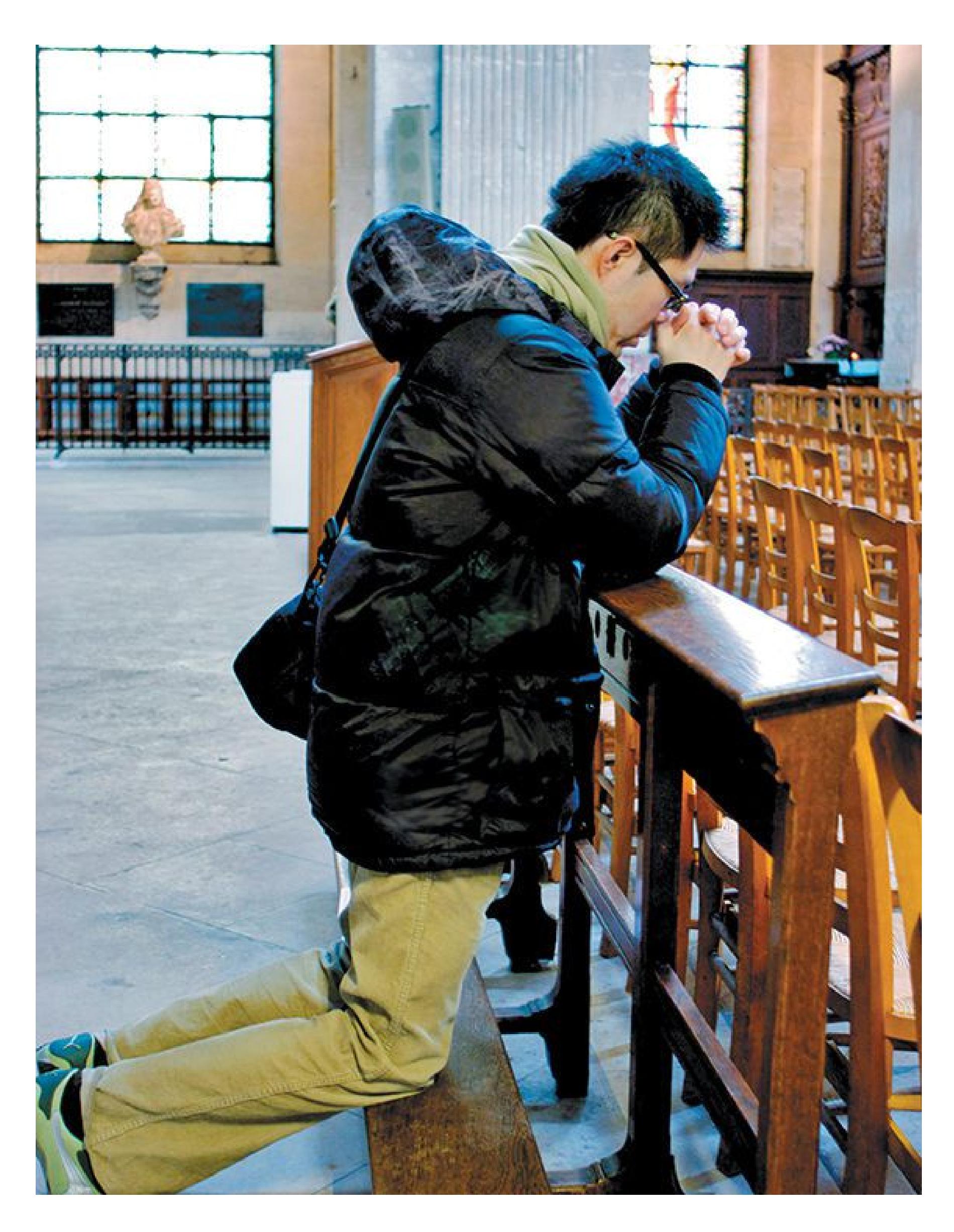

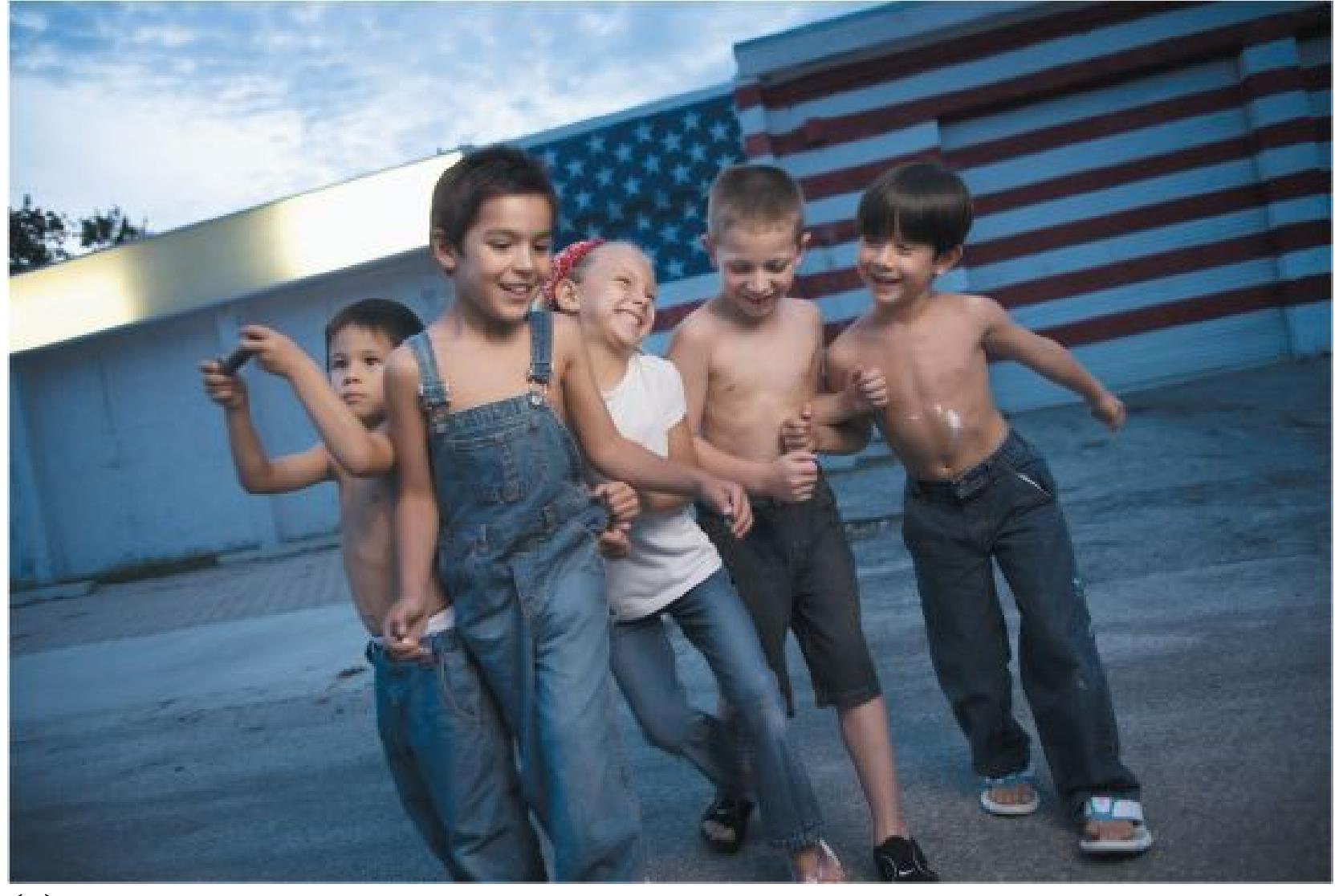

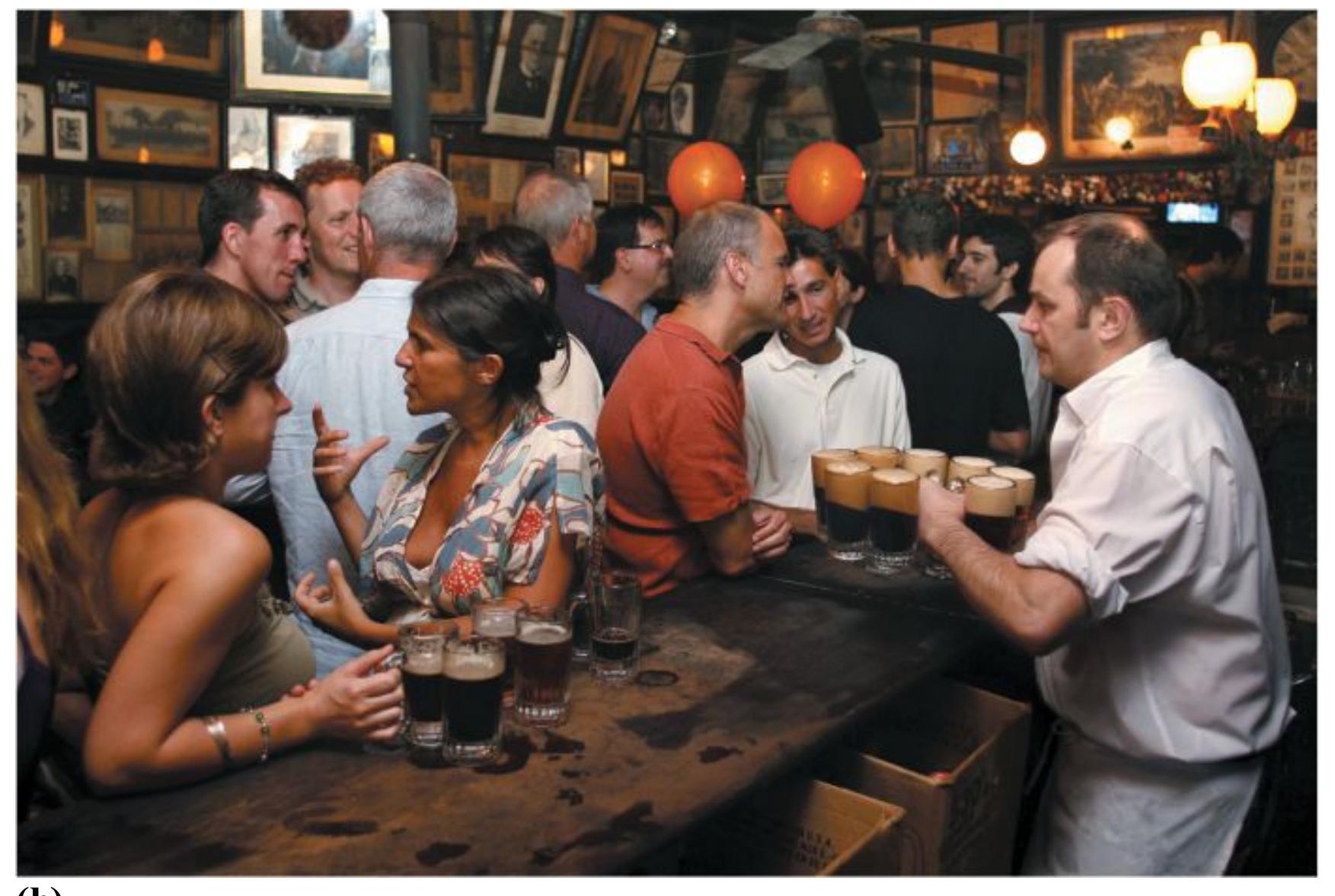

**(a)**

**(b)**

# FIGURE 1.18

# Cultural Differences

**(a)** Westerners tend to be "independent" and autonomous, stressing their individuality. **(b)** Easterners—such as this Cambodian family—tend to be more "interdependent," stressing their sense of being part of a collective.

The culture in which people live shapes many aspects of their daily lives. Pause for a moment and think about the following questions: How do people decide what is most important in their lives? How do people relate to family members? to friends? to colleagues at work? How should people spend their leisure time? How do they define themselves in relation to their own culture—or across cultures?

Culture shapes beliefs and values, such as the extent to which people should emphasize their own interests versus the interests of the group. This effect is more apparent when we compare phenomena across cultures. Culture instills certain rules, called *norms*, which specify how people ought to behave in different contexts. For example, norms tell us not to laugh uproariously at funerals and to keep quiet in libraries. Culture can influence our biology by altering our behavior. For instance, diet is partly determined by culture, and some diets have epigenetic effects. Culture also has material aspects, such as media, technology, health care, and transportation. Many people find it hard to imagine life without computers, televisions, cell phones, and cars. We also recognize that each of these inventions has changed the fundamental ways in which people interact. Historical and social changes can have similar effects. For instance, the increased participation of women in the workforce has changed the nature of contemporary Western culture in numerous ways, from a fundamental change in how women are viewed to more practical changes, such as people marrying and having children later in life, a greater number of children in day care, and a greater reliance on convenient, fast foods.

# What are cultural norms?

**Answer:** socially upheld rules regarding how people ought to behave in certain situations

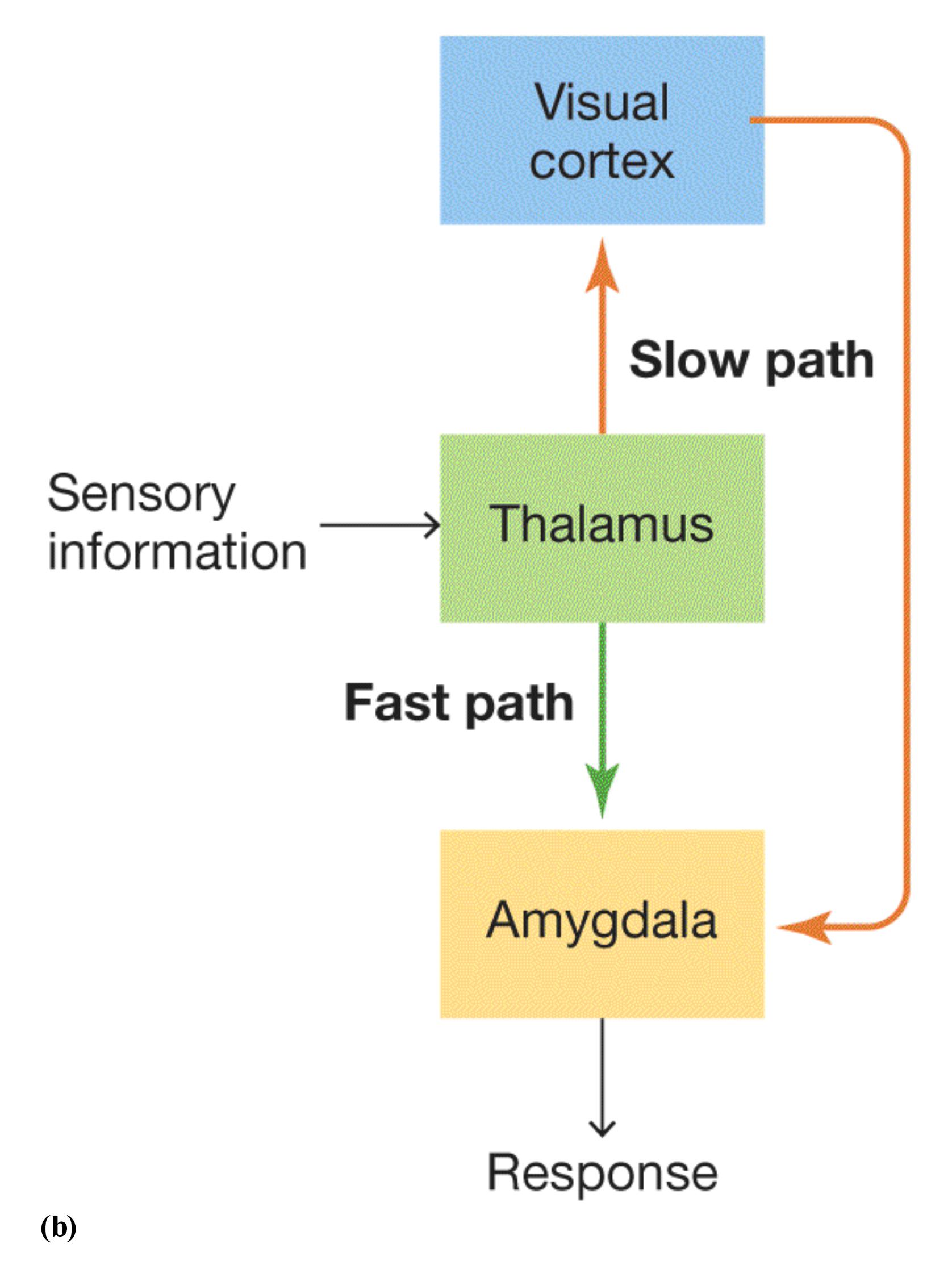

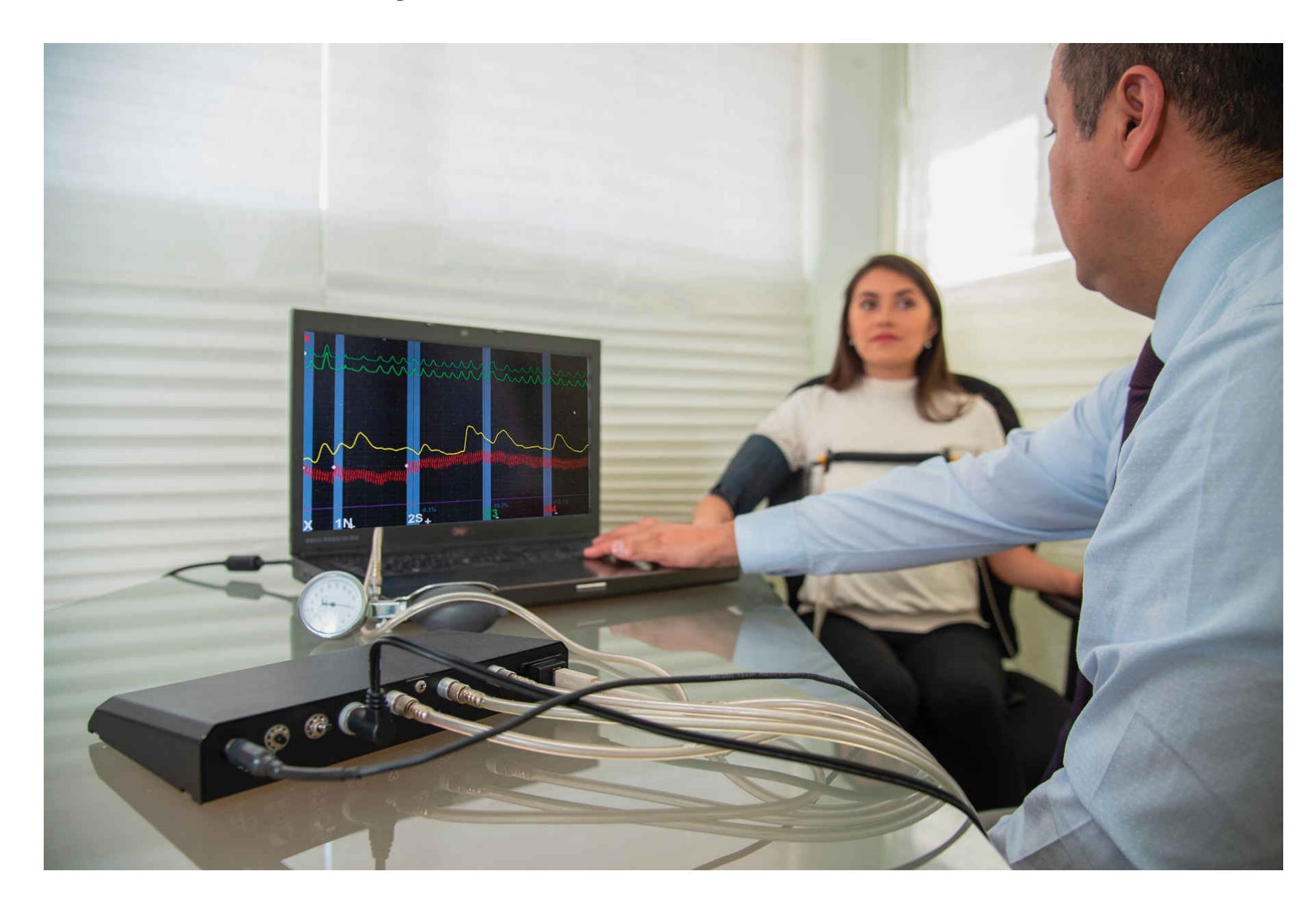

# 1.11 Psychological Science Crosses Levels of Analysis

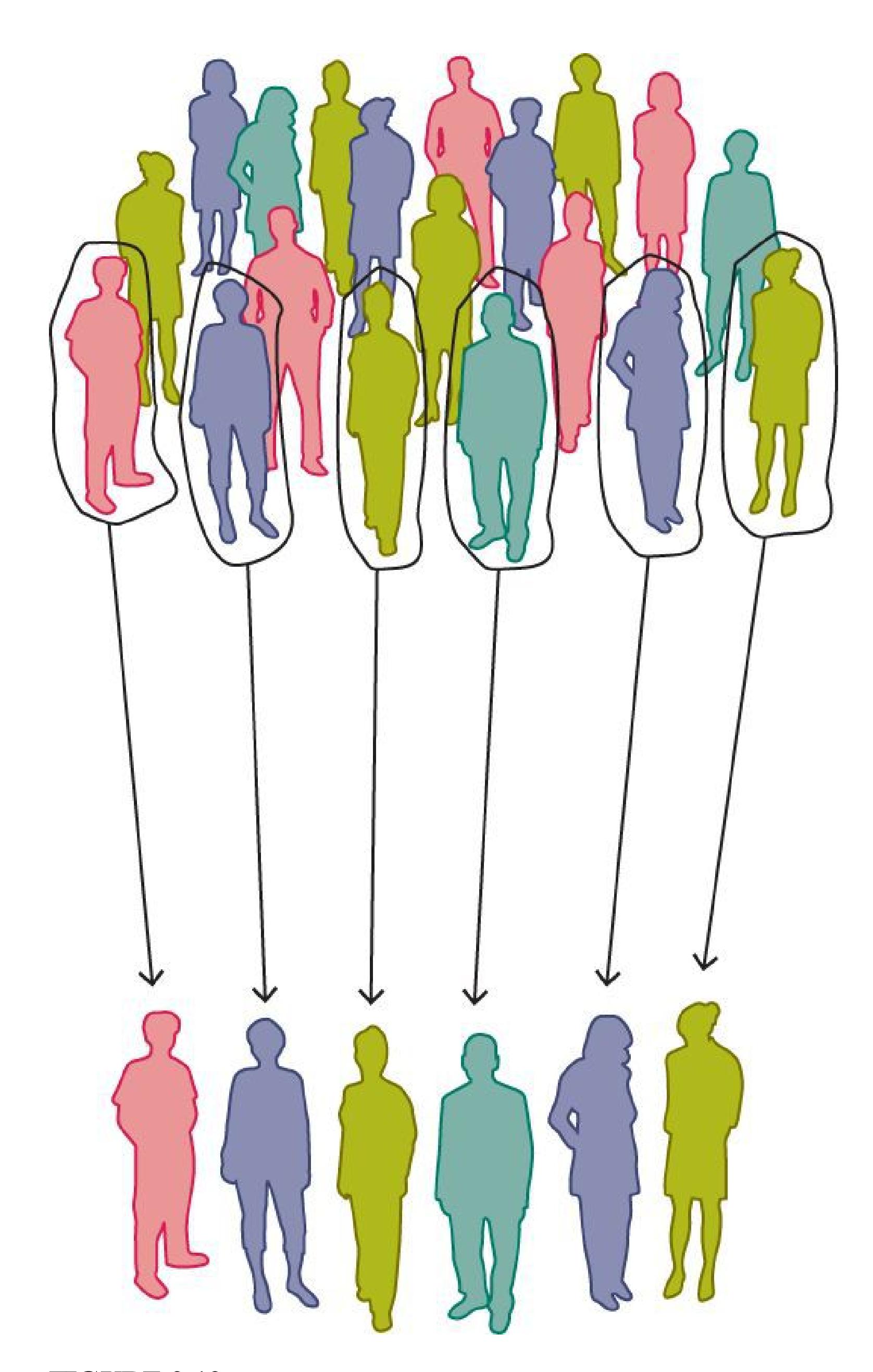

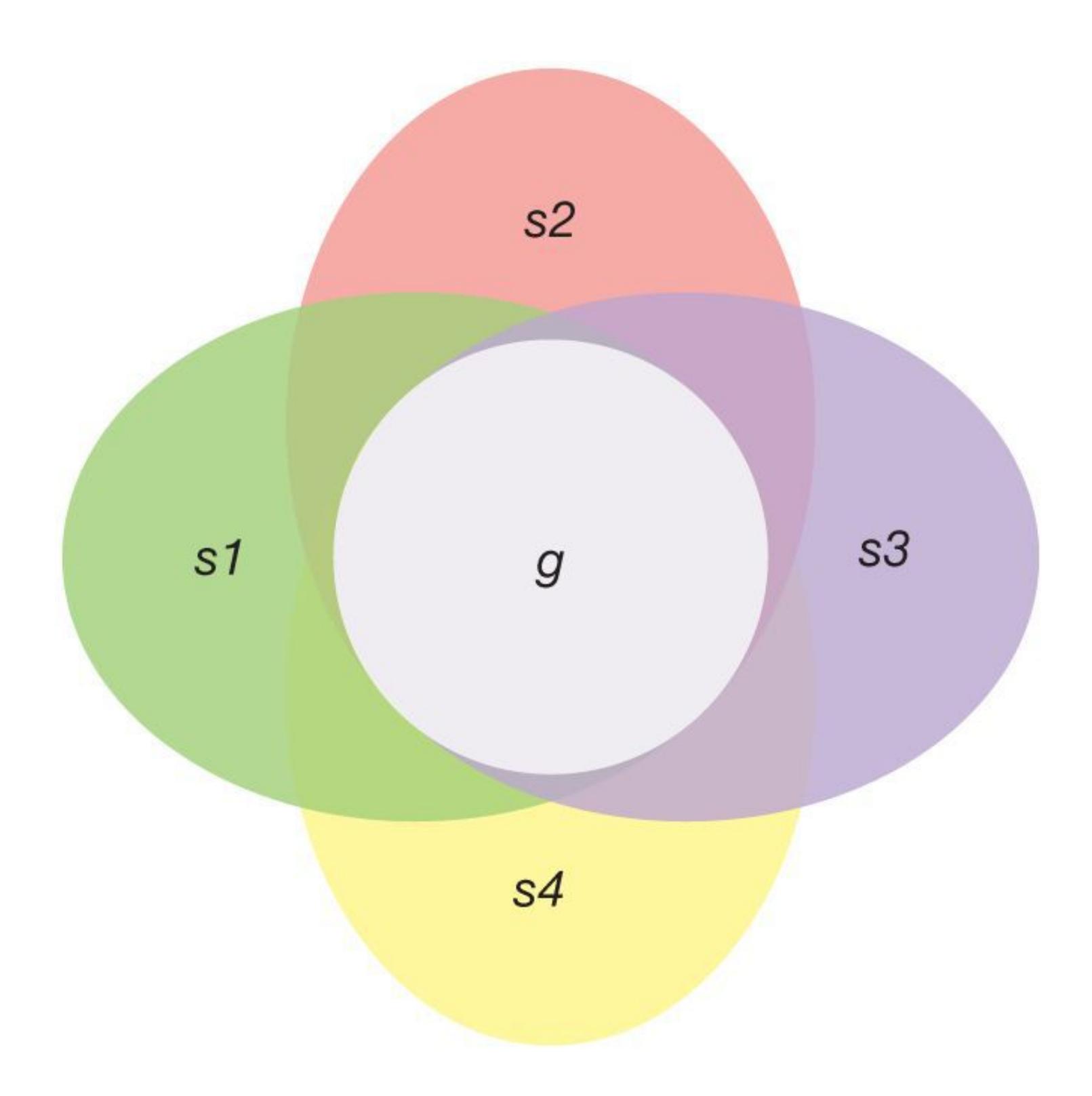

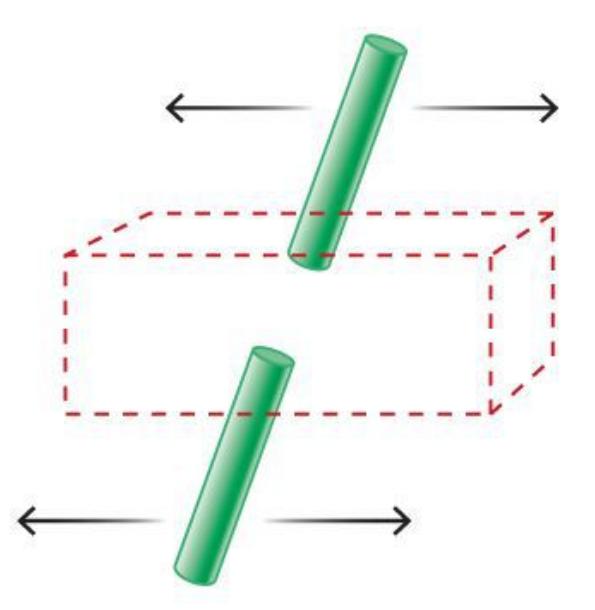

Four broadly defined levels of analysis reflect the most common research methods for studying mind and behavior (**FIGURE 1.19**). The *biological level of analysis* deals with how the physical body contributes to mind and behavior (such as through the chemical and genetic processes that occur in the body). The *individual level of analysis* focuses on individual differences in personality and in the mental processes that affect how people perceive and know the world. The *social level of analysis* involves how group contexts affect the ways in which people interact and influence each other. The first three together are sometimes referred to as the [biopsychosocial model.](#page-63-0) On top of that is the *cultural level of analysis*, which explores how people's thoughts, feelings, and actions are similar or different across cultures. Differences between cultures highlight the role that cultural experiences play in shaping psychological processes, whereas similarities between cultures reveal evidence for universal phenomena that emerge regardless of cultural experiences.

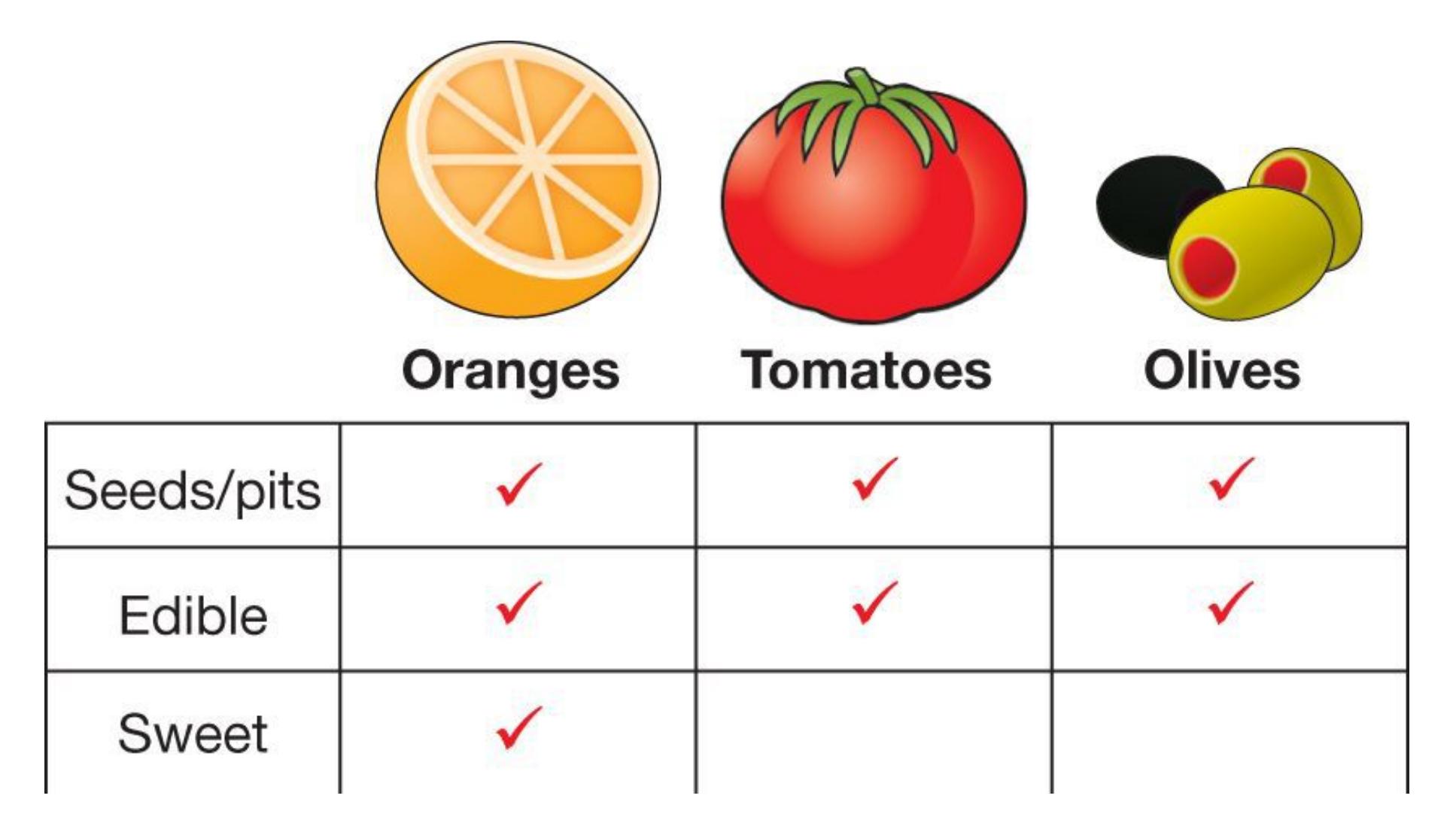

| LEVEL | FOCUS | WHAT IS STUDIED? |

|------------|-------------------------------------------------------------------------|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Biological | Brain systems

Neurochemistry

Genetics | Neuroanatomy, animal research, brain imaging

Neurotransmitters and hormones, animal studies, drug studies

Gene mechanisms, heritability, twin and adoption studies |

| Individual | Individual differences

Perception and cognition

Behavior | Personality, gender, developmental age groups, self-concept

Thinking, decision making, language, memory, seeing, hearing

Observable actions, responses, physical movements |

| Social | Interpersonal behavior

Social cognition | Groups, relationships, persuasion, influence, workplace

Attitudes, stereotypes, perceptions |

| Cultural | Thoughts, actions, behaviors-in different societies and cultural groups | Norms, beliefs, values, symbols, ethnicity |

**FIGURE 1.19**

# Levels of Analysis

Studying a psychological phenomenon at one level of analysis (e.g., behavioral or neural data alone) has traditionally been the favored approach, but these days researchers have started to explain behavior at several levels of analysis. By crossing levels in this way, psychologists are able to provide a more complete picture of mental and behavioral processes.

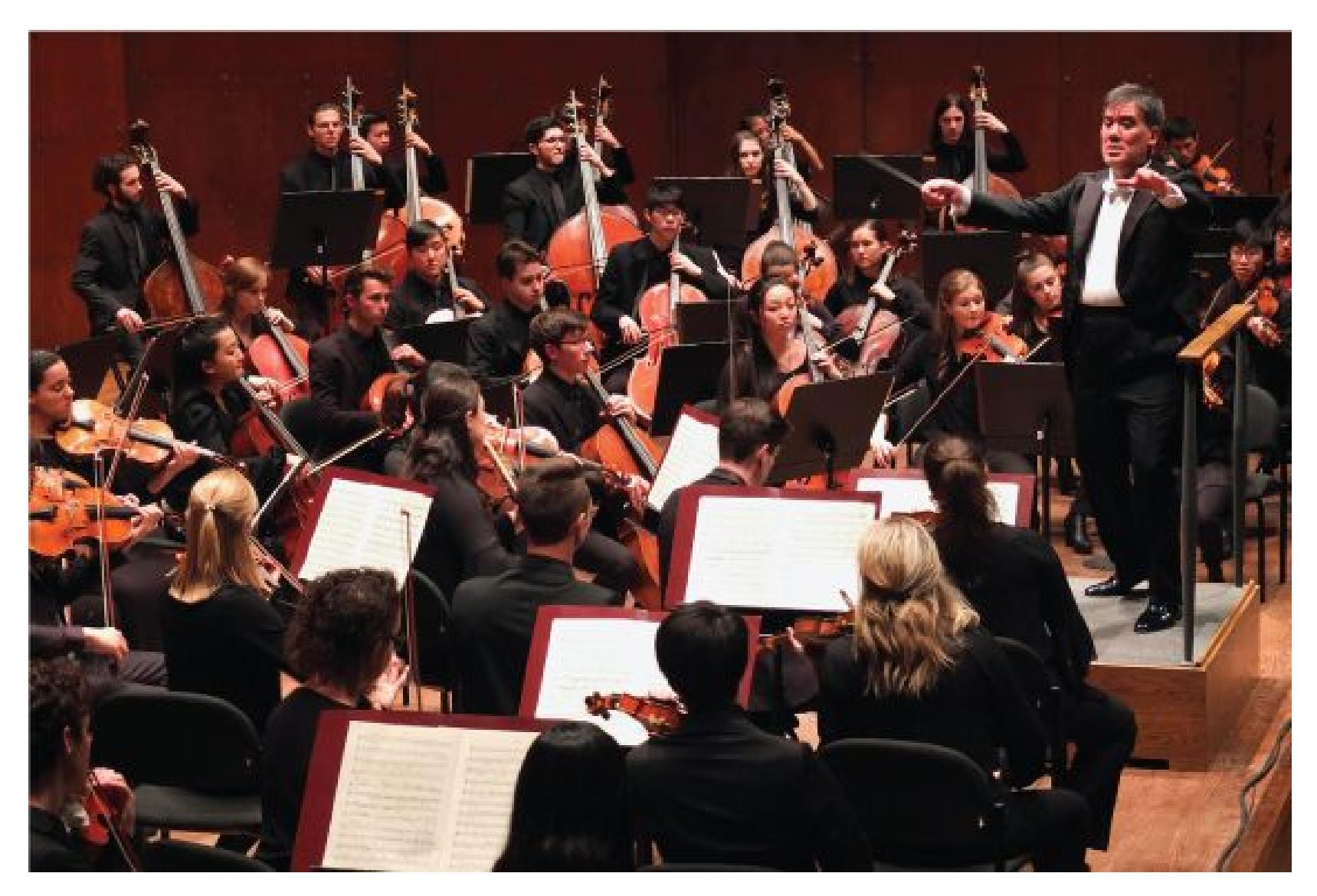

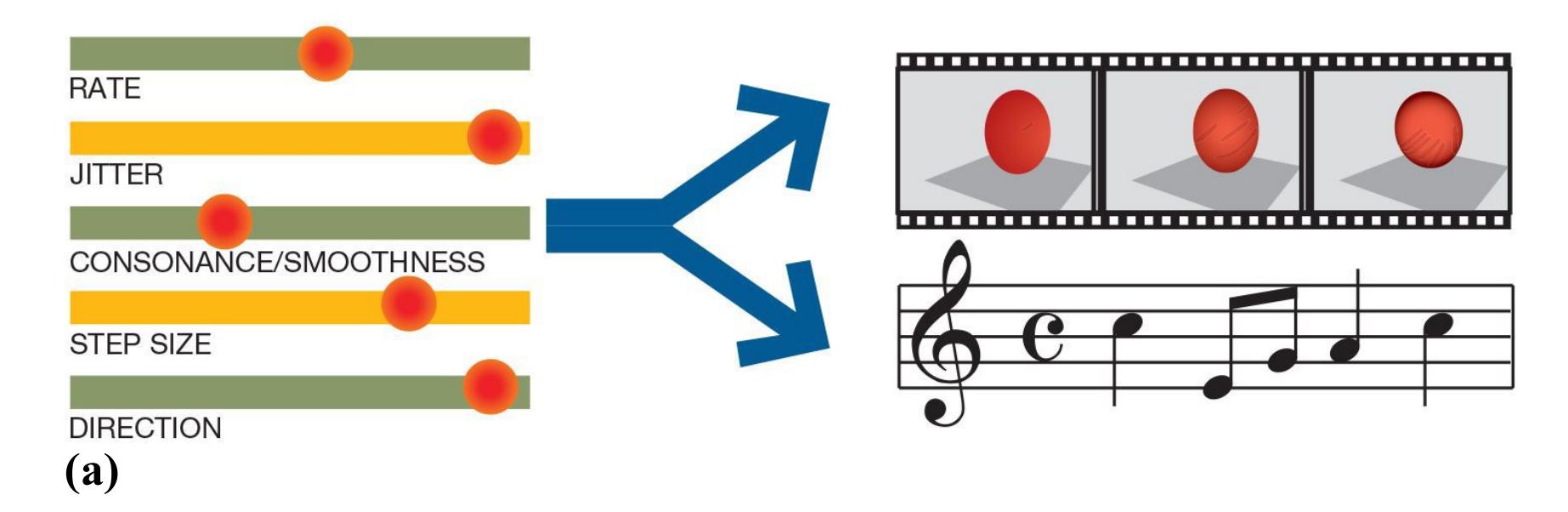

To understand how research is conducted at the different levels, consider the many ways psychologists have studied listening to music (Hallam et al., 2016). Why do you like some kinds of music and not others? Do you prefer some types of music when you are in a good mood and other types when you are in a bad mood? If you listen to music while you study, how does it affect how you learn?

At the biological level of analysis, for instance, researchers have studied the effects of musical training. They have shown that training can change not only how the brain functions but also its anatomy, such as by changing brain structures associated with learning and memory (Herdener et al., 2010). Interestingly, music does not affect the brain exactly the way other types of sounds, such as the spoken word, do. Instead, music recruits brain regions involved in a number of mental processes, such as those involved in mood and memory (Levitin & Menon, 2003; Peretz & Zatorre, 2005). Music appears to be treated by the brain as a special category of auditory information. For this reason, patients with certain types of brain injury become unable to perceive tones and melody but can understand speech and environmental sounds perfectly well.

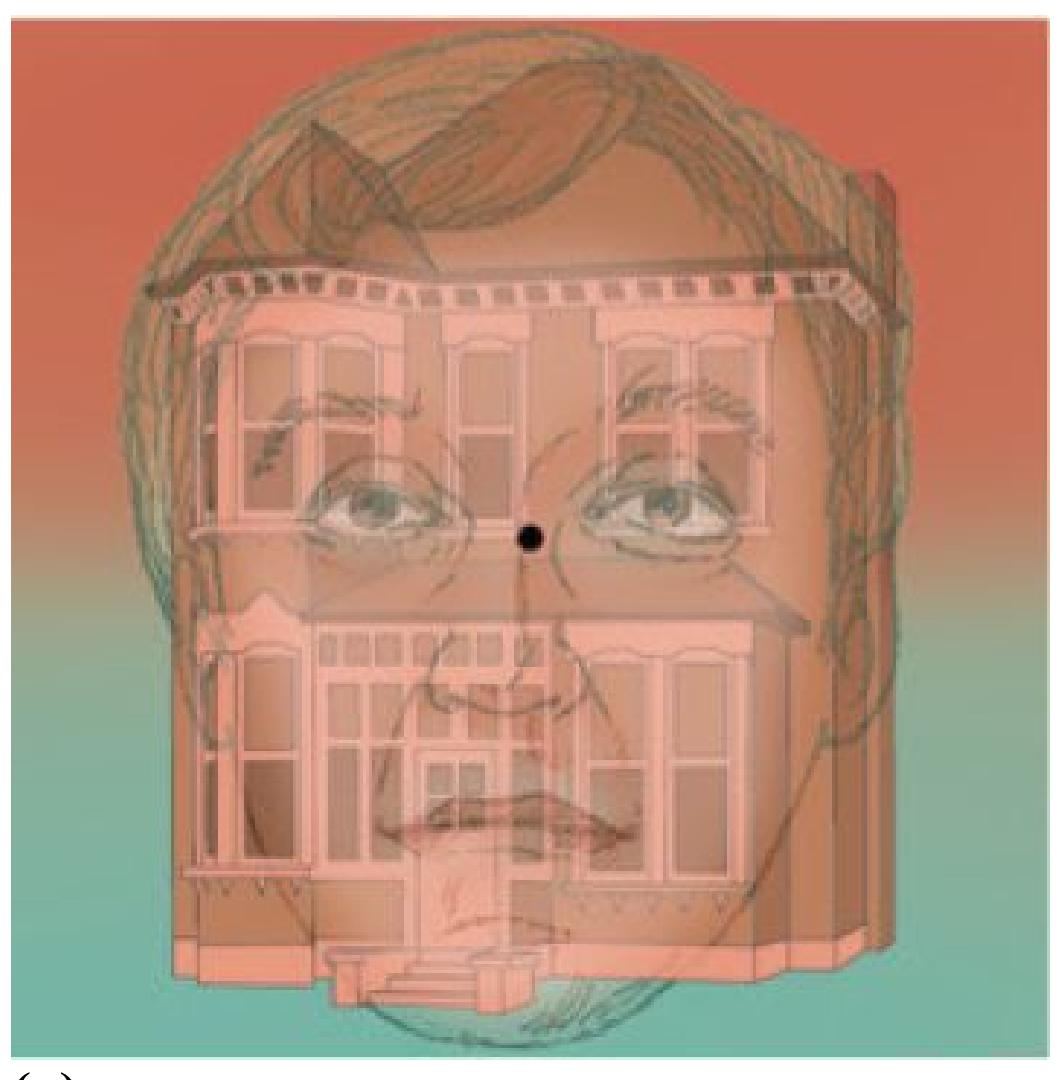

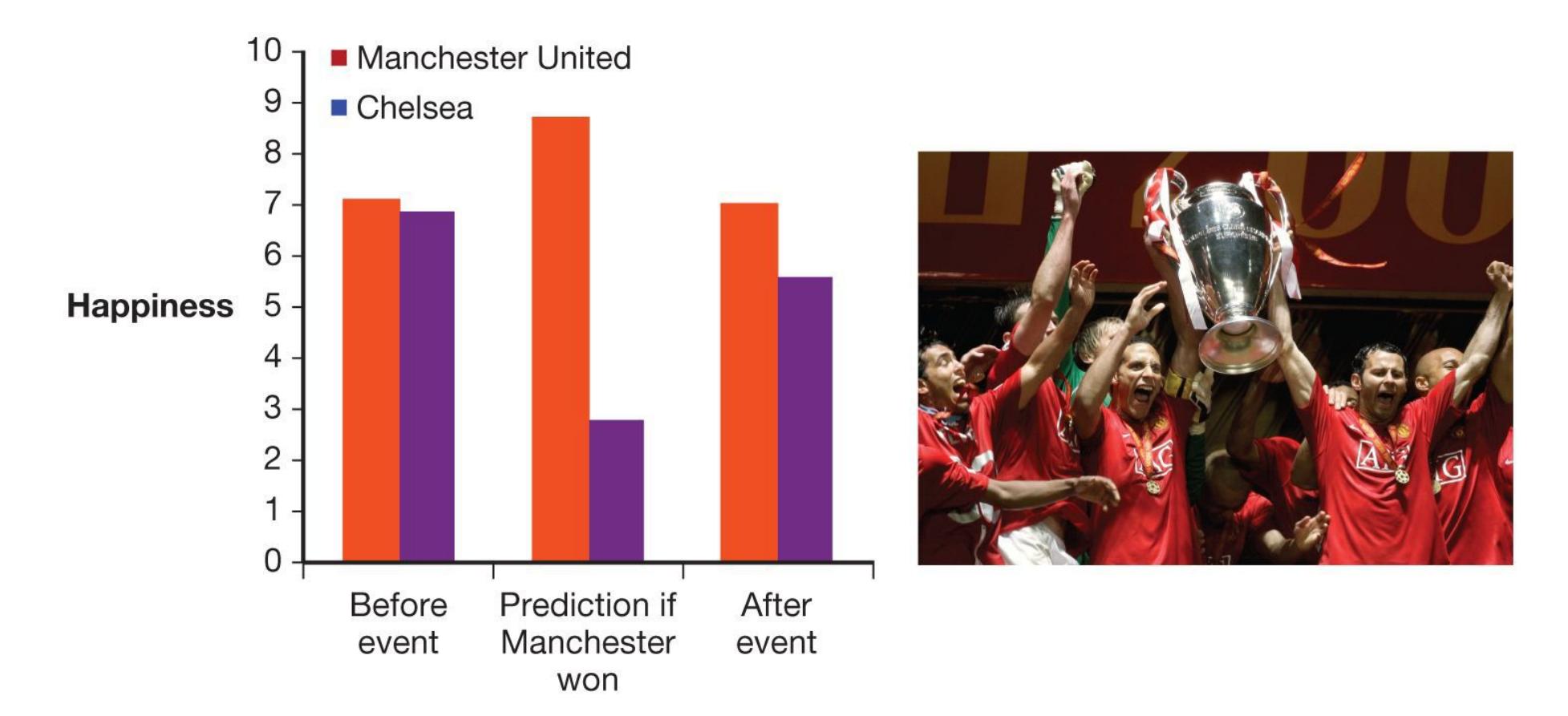

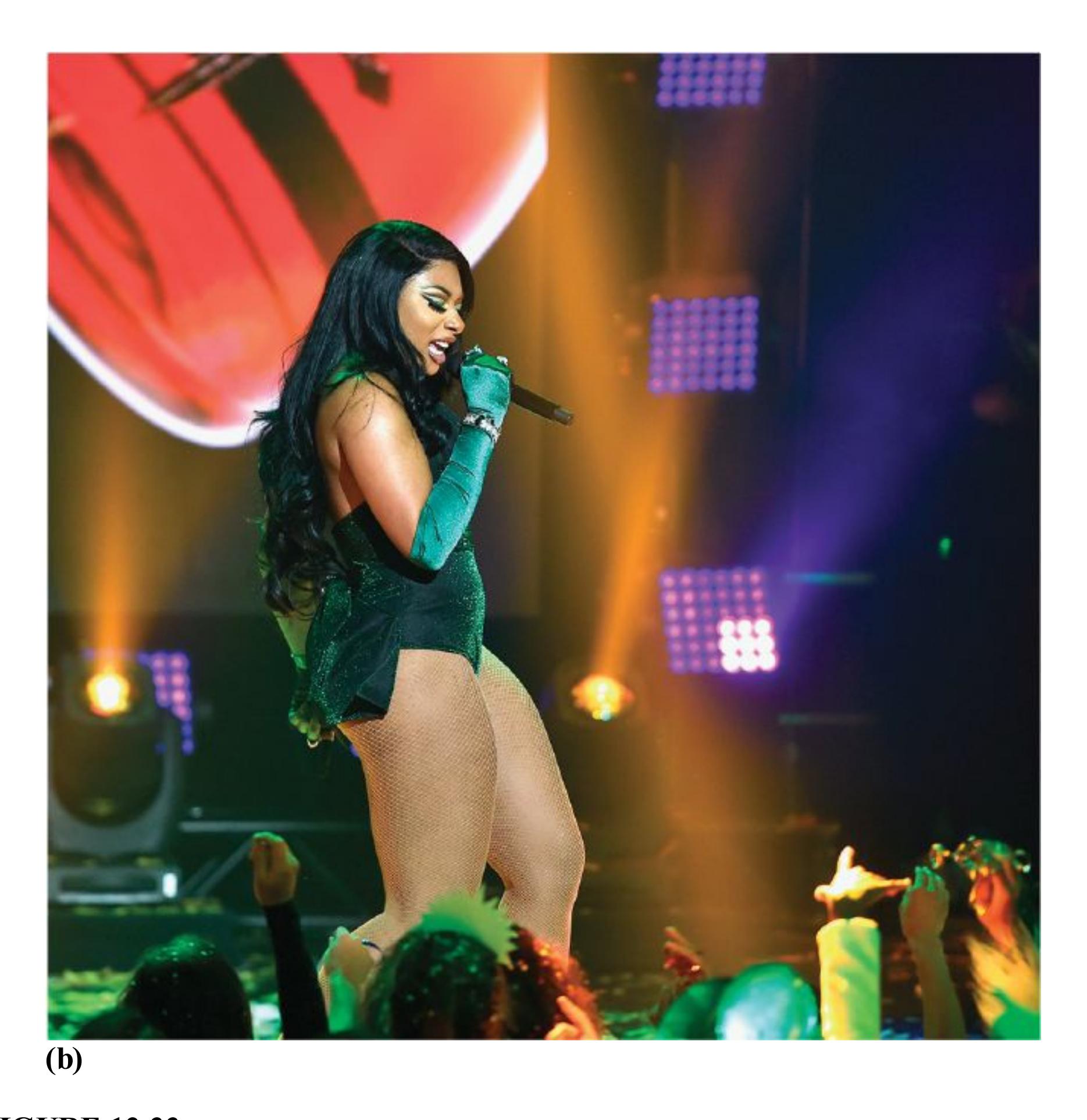

Working at the individual level of analysis, researchers have used laboratory experiments to study music's effects on mood, memory, decision making, and various other mental states that exist within an individual person (Levitin, 2006). In one study, music from participants' childhoods evoked specific memories from that period (Janata, 2009; **FIGURE 1.20**). Moreover, music affects emotions and thoughts. Listening to sad background music leads young children to interpret a story negatively, whereas listening to happy background music leads them to interpret the story much more positively (Ziv & Goshen, 2006). Our cognitive expectations also shape how we experience music (Collins et al., 2014).

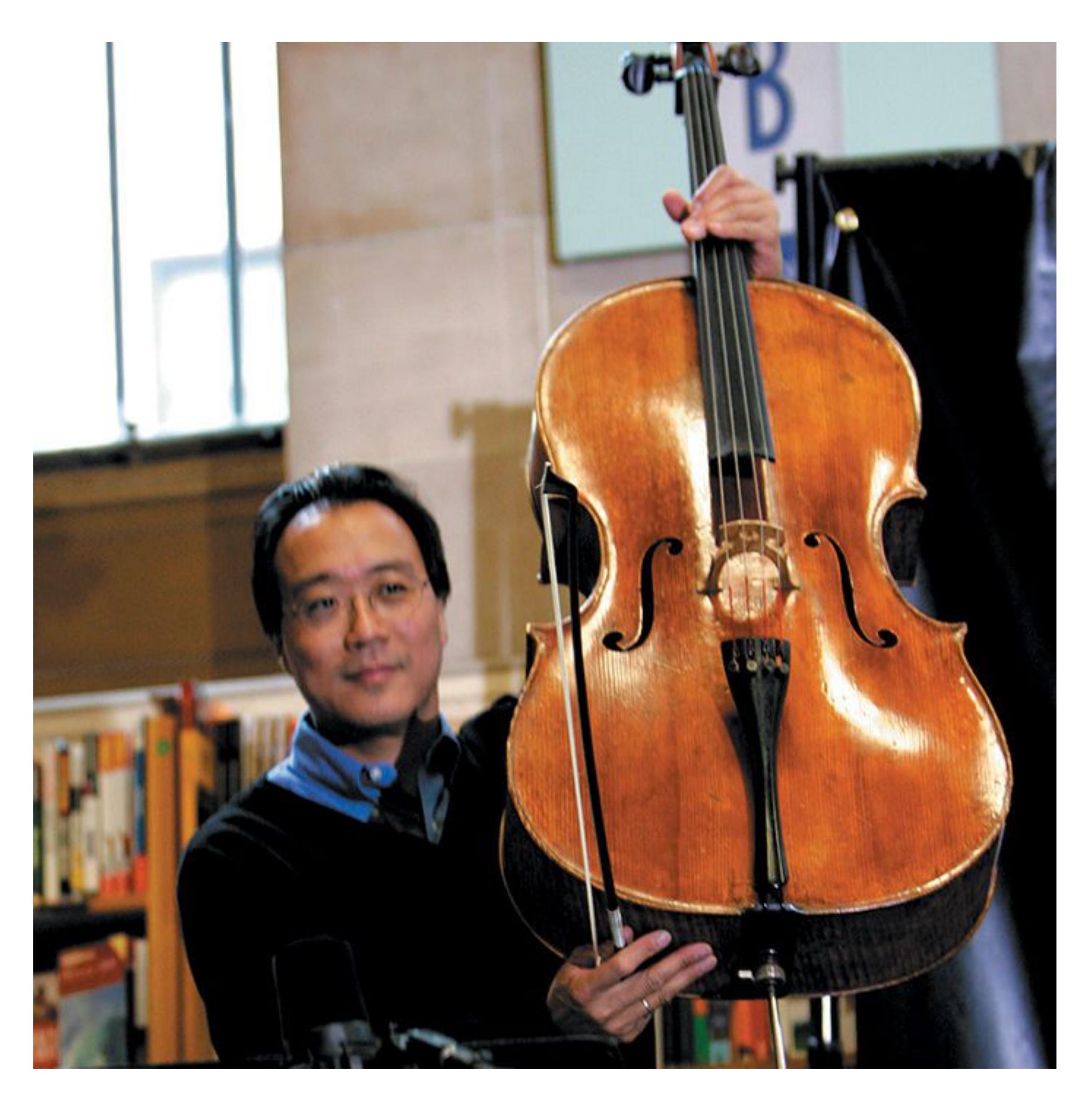

# FIGURE 1.20

# Your Brain on Music

The researcher Petr Janata played familiar and unfamiliar music to study participants. Activity in green indicates familiarity with the music, activity in blue indicates emotional reactions to the music, and activity in red indicates memories from the past. The yellow section in the frontal lobe links together familiar music, emotions, and memories.

A study of music at the social level of analysis might investigate how the effect of music changes or the types of music people prefer change when they are in groups compared with when they are alone. For example, music reduces stress regardless of context but especially when enjoyed in the presence of others (Linnemann et al., 2016). Romantic partners can also influence the way we experience music. For example, in heterosexual couples, men experience more stress reduction from listening to music than their partners do, particularly when the two individuals have shared music preferences (Wuttke-Linnemann et al., 2019).

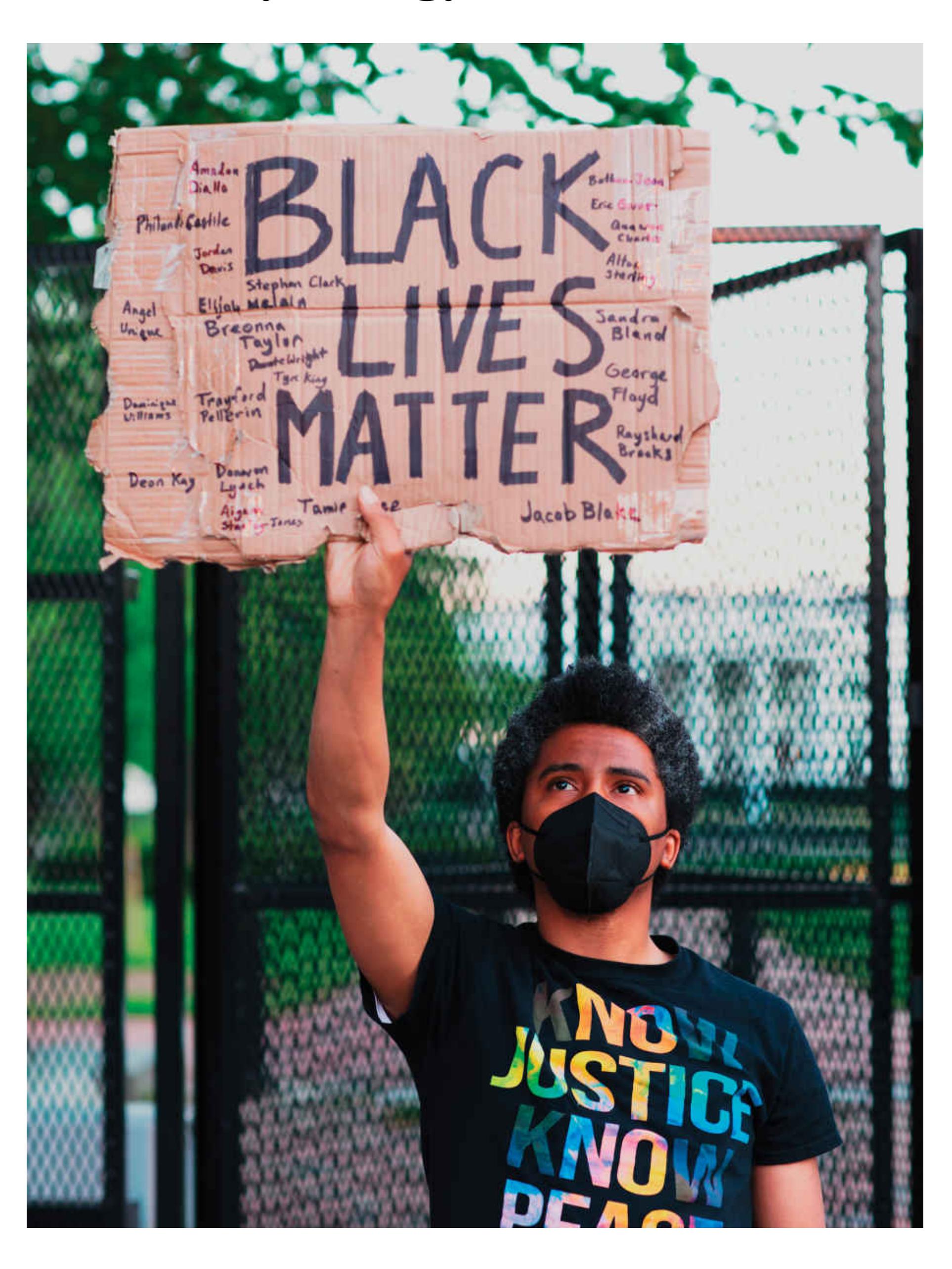

The cross-cultural study of music preferences has developed into a separate field, *ethnomusicology*. One finding from this field is that African music has rhythmic structures different from those in Western music (Agawu, 1995), possibly because of the important role of dancing and drumming in many African cultures. Because musical preferences differ across cultures, some psychologists have noted that attitudes about outgroup members can color perceptions of their musical styles. For example, researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom found that societal attitudes toward rap and hip-hop music revealed subtle prejudicial attitudes against Black people and a greater willingness to discriminate against them (Reyna et al., 2009).

Combining the levels of analysis usually provides more insights than working within only one level. Psychologists may also collaborate with researchers from other scientific fields, such as biology, computer science, physics, anthropology, and sociology. Such collaborations are called *interdisciplinary*. For example, psychologists interested in understanding the hormonal basis of obesity might work with geneticists exploring the heritability of obesity as well as with social psychologists studying human beliefs about eating. Throughout this book, you will see how this multilevel, multidisciplinary approach has led to breakthroughs in understanding psychological activity.

**Suppose a research study explores people's memory for song lyrics. At what level of analysis are the researchers working?**

**Answer:** the individual level

# **Glossary**

# biopsychosocial model

An approach to psychological science that integrates biological factors, psychological processes, and social-contextual influences in shaping human mental life and behavior.

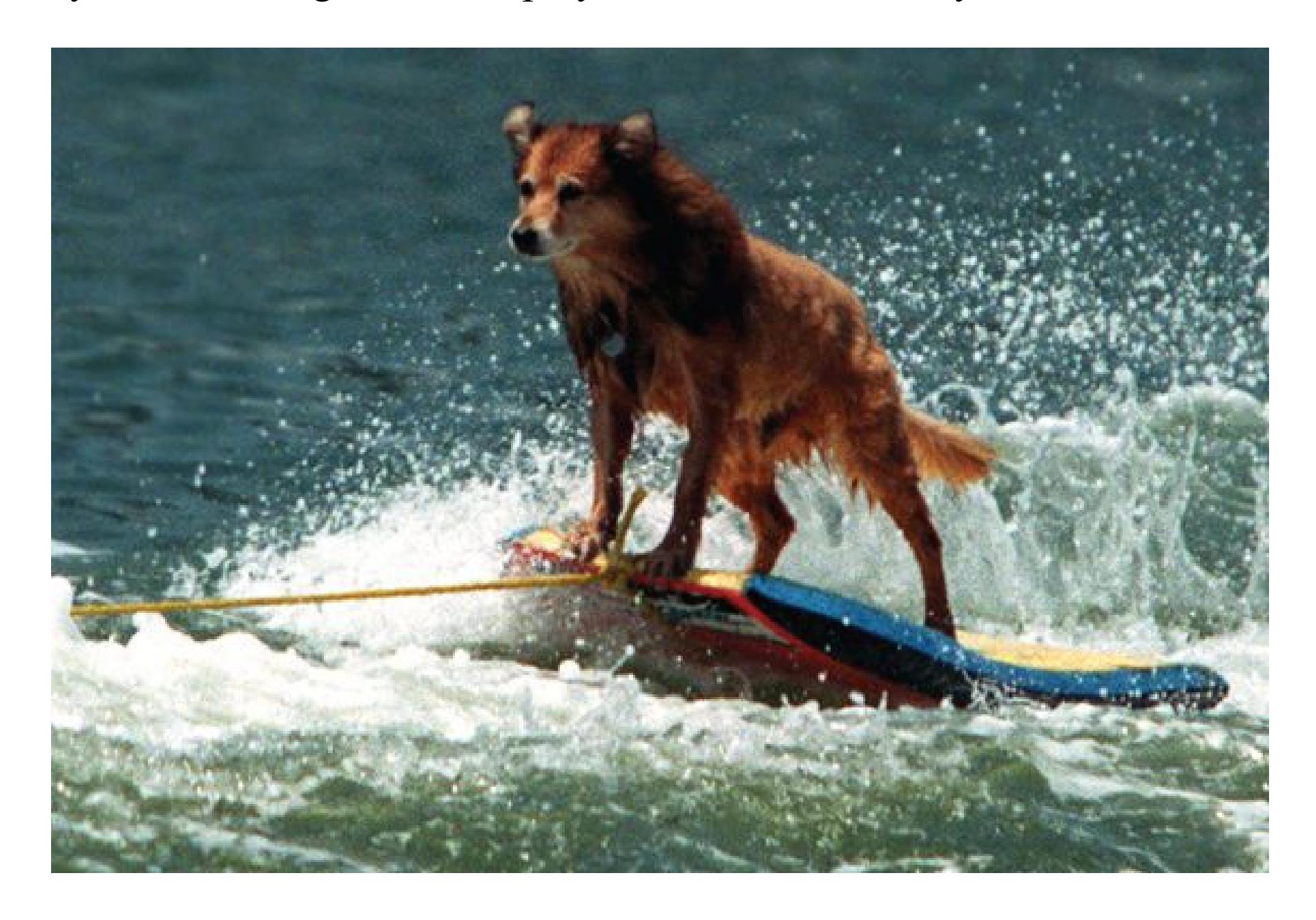

# 1.12 Psychological Education Embraces the Science of Learning

The study of how people learn and retain new information is one of the oldest and most robust areas of research in psychology. It is only appropriate, then, that psychologists would apply this knowledge when teaching students about their field. Throughout this book, we highlight some of the tips and tricks that psychologists have discovered to improve how people study and learn. The learning-science principles identified in psychology research can be effective in many contexts in and out of the classroom, so you should put them to good use in all of your courses and in whatever career you ultimately choose. These topics and the science behind them are covered in depth in [Chapter 6](#page-550-0).

Despite a long history of studying learning in the lab, psychologists have only recently found ways to translate those results into the world of education (Roediger, 2013). However, some of the most effective learning strategies are easy to deploy and have been put to use in classrooms, benefiting students of all ages (Dunlosky et al., 2013). The following are among the most effective strategies, and they are put into practice in this text where possible.

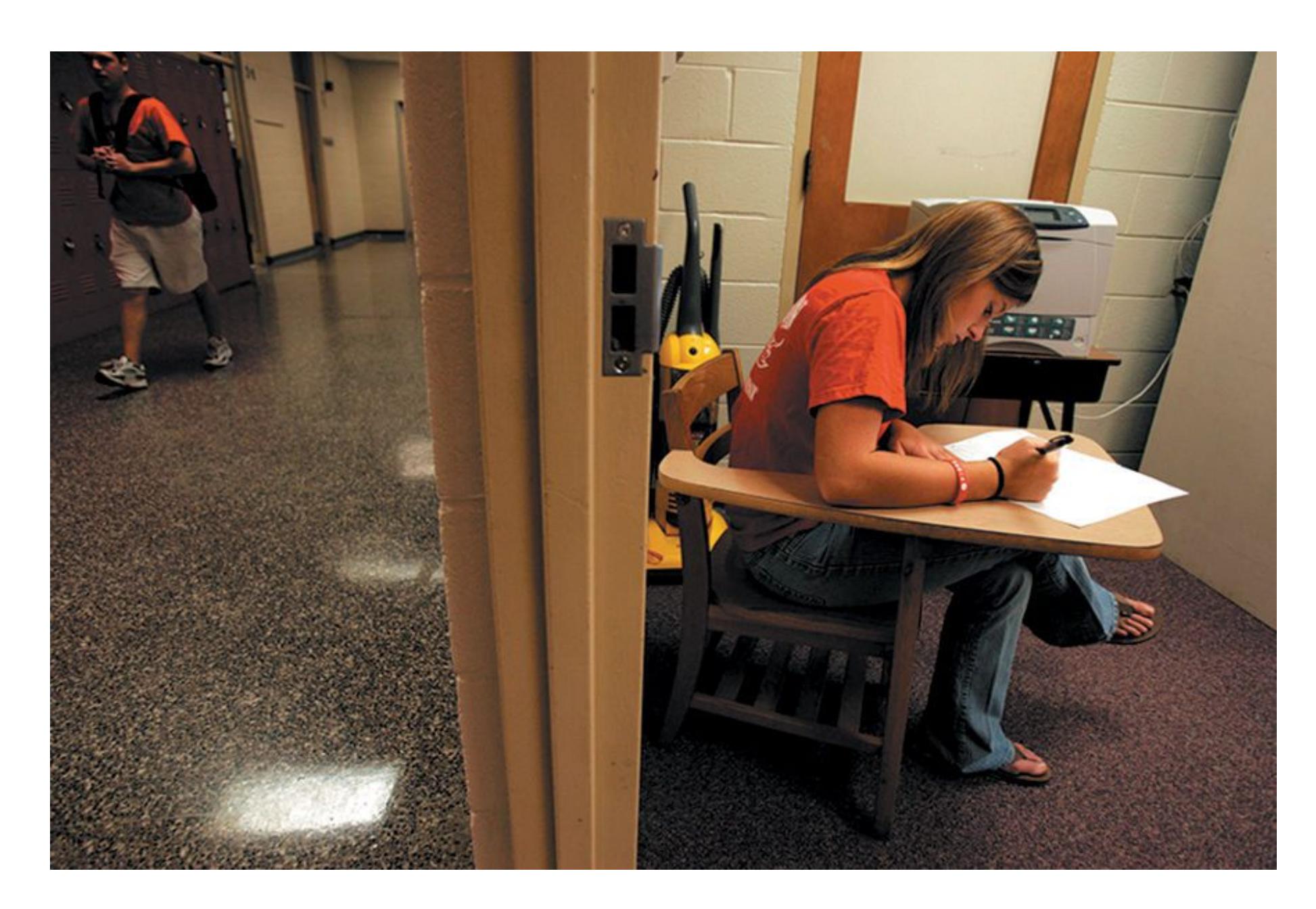

**DISTRIBUTED PRACTICE** At some point in their college career, most students learn by experience that cramming for an exam is an ineffective way to study (**FIGURE 1.21**). [Distributed practice—](#page-66-0)learning material in bursts over a prolonged time frame—is the opposite of cramming and is one of the best ways to learn (Benjamin & Tullis, 2010). Why does distributed practice work? It might be that the extra work it takes to remember material you learned before switching to something else is beneficial. It might also be the case that after the initial study period, each time you study the material you are reminded of that first time. Distributed practice might also promote better learning because every time you pull up a memory and then remember it again, it gets stronger.

# FIGURE 1.21

# Distributed Practice

Distributing practice sessions across time is one of the proven ways to increase memory. The student shown cramming in this photo is missing an opportunity to benefit from distributed practice.