# The Oxford Handbook of

## EEG

## FREQUENCY

# T h e Ox for d H a n db o ok of

# **EEG FREQUENCY**

## OXFORD LIBR ARY OF PSYCHOLOGY

*The Oxford Handbook of Internet Psychology* Edited by Adam Joinson, Katelyn McKenna, Tom Postmes, and Ulf-Dietrich Reips

*The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search*

Edited by Ute-Christine Klehe and Edwin van Hooft

*The Oxford Handbook of Parenting and Moral Development*

Edited by Deborah J. Laible, Gustavo Carlo, Laura M. Padilla Walker

*The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health* Edited by Brenda Major,

John F. Dovidio, and Bruce G. Link

*The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Learning and Cognition* Edited by Marc Marschark and Harry Knoors

*The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition* Edited by Albert Newen, Leon De Bruin, and Shaun Gallagher

*The Oxford Handbook of Attention* Edited by Anna C. Nobre and Sabine Kastner

*The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology* Edited by Thomas H. Ollendick, Susan W. White, and Bradley A. White

*The Oxford Handbook of Group Creativity and Innovation*

Edited by Paul B. Paulus and Bernard A. Nijstad

*The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior*

Edited by Philip M. Podsakoff, Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff

*The Oxford Handbook of Digital Technologies and Mental Health* Edited by Marc N. Potenza, Kyle Faust, David Faust

*The Oxford Handbook of Sexual and Gender Minority Mental Health* Edited by Esther D. Rothblum

*The Oxford Handbook of Psychological Situations*

Edited by John F. Rauthmann, Ryne Sherman, David C. Funder

*The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, 2e*

Edited by Richard Ryan

*The Oxford Handbook of Integrative Health Science*

Edited by Carol D. Ryff and Robert F. Krueger

*The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 3e*

Edited by C.R. Snyder, Shane J. Lopez, Lisa M. Edwards, Susana C. Marques

*The Oxford Handbook of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy*

Edited by Michaela A. Swales *The Oxford Handbook of Music and*

*the Brain* Edited by Michael H. Thaut and Donald A. Hodges

*The Oxford Handbook of Expertise* Edited by Paul Ward, Jan Maarten Schraagen, Julie Gore, and Emilie M. Roth

*The Oxford Handbook of Singing* Edited by Graham F. Welch, David M. Howard, and John Nix

*The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Behavioral Endocrinology* Edited by Lisa L. M. Welling and Todd K. Shackelford

*The Oxford Handbook of Autism and Co-Occurring Psychiatric Conditions* Edited by Susan W. White, Brenna B. Maddox, Carla A. Mazefsky

*The Oxford Handbook of Adolescent Substance Abuse*

Edited by Robert A. Zucker and Sandra A. Brown

# The Oxford Handbook of

# **EEG FREQUENCY**

*Edited by*

PHILIP GABLE, MATTHEW MILLER, EDWARD BERNAT

### Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2022

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2022 Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

> You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

> British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–289834–0

DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192898340.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breast-feeding

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

## Contents

| List of Contributors | ix |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|------|

| Foreword | xiii |

| Preface | xv |

| PART I | |

| 1. Introduction: Methods for Collecting EEG Data for Frequency

Analyses in Humans

Philip A. Gable and Matthew W. Miller | 3 |

| 2. Logic behind EEG Frequency Analysis: Basic Electricity and

Assumptions

Kyle J. Curham and John J. B. Allen | 15 |

| 3. From Neural Oscillations to Cognitive Processes

Andreas Keil and Nina Thigpen | 40 |

| 4. Time-Frequency Decomposition Methods for Event-Related

Potential Analysis

Selin Aviyente | 65 |

| 5. Time Frequency Analyses in Event-Related Potential

Methodologies

Anna Weinberg, Paige Ethridge,

Belel Ait Oumeziane, and Dan Foti | 88 |

| 6. The Relationship Between Evoked and Induced EEG/MEG

Changes: Going Beyond Labels

Ali Mazaheri | 115 |

| 7. Frequency Analysis of the Monkey Neocortical Local

Field Potential

Steven L. Bressler | 131 |

| 8. Gamma Activity in Sensory and Cognitive Processing

DANIEL STRÜBER AND CHRISTOPH S. HERRMANN | 145 |

| 9. Frontal Midline Theta as a Model Specimen of Cortical Theta

JAMES F. CAVANAGH AND MICHAEL X COHEN | 178 |

| 10. The Role of Alpha and Beta Oscillations in the Human EEG during

Perception and Memory Processes

SEBASTIAN MICHELMANN, BENJAMIN GRIFFITHS,

AND SIMON HANSLMAYR | 202 |

| 11. Theory and Research on Asymmetric Frontal Cortical Activity as

Assessed by EEG Frequency Analyses

EDDIE HARMON-JONES, TAYLOR POPP, AND PHILIP A. GABLE | 220 |

| 12. Oscillatory Activity in Sensorimotor Function

BERNADETTE C. M. VAN WIJK | 259 |

| PART III | |

| 13. EEG Frequency Development across Infancy and Childhood

KIMBERLY CUEVAS AND MARTHA ANN BELL | 293 |

| 14. Developmental Research on Time-Frequency Activity in

Adolescence and Early Adulthood

STEPHEN M. MALONE, JEREMY HARPER, AND WILLIAM G. IACONO | 324 |

| 15. Theta-Beta Power Ratio: An Electrophysiological Signature of

Motivation, Attention and Cognitive Control

DENNIS J. L. G. SCHUTTER AND J. LEON KENEMANS | 352 |

| 16. Cortical Source Localization in EEG Frequency Analysis

WANZE XIE AND JOHN E. RICHARDS | 377 |

| 17. Frequency Characteristics of Sleep

ALPÁR S. LÁZÁR, ZSOLT I. LÁZÁR, AND RÓBERT BÓDIZS | 401 |

| 18. A Review of Oscillatory Brain Dynamics in Schizophrenia

KEVIN M. SPENCER | 434 |

| 19. EEG Frequency Techniques for Imaging Control Functions

in Anxiety

JASON S. MOSER, COURTNEY LOUIS, LILIANNE GLOE,

STEFANIE RUSSMAN BLOCK, AND SPENCER FIX | 464 |

| PART IV | |

vi Contents

### **PART II**

Contents vii

| PART IV | | |

|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-----|-----|

| 20. Bivariate Functional Connectivity Measures for Within- and

Cross-Frequency Coupling of Neuronal Oscillations

J. MATIAS PALVA AND SATU PALVA | 495 | |

| 21. Multivariate Methods for Functional Connectivity Analysis

SELIN AVIYENTE | 514 | |

| 22. Brain Stimulation Approaches to Investigate EEG Oscillations

FLORIAN H. KASTEN AND CHRISTOPH S. HERRMANN | 532 | |

| 23. Parameterizing Neural Field Potential Data

BRADLEY VOYTEK | 563 | |

| Index | | 579 |

## [List of Contributors](#page-5-0)

**John J. B. Allen**, Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

**Selin Aviyente**, Professor, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

**Martha Ann Bell**, University Distinguished Professor, Department of Psychology, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA

**Róbert Bódizs**, Senior Research Fellow, Semmelweis University, Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Budapest, Hungary

**Steven L. Bressler**, Professor, Center for Complex Systems and Brain Sciences, Department of Psychology, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL

**James F. Cavanagh**, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

**Michael X Cohen**, Assistant Professor, Donders Centre for Neuroscience & Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

**Kimberly Cuevas**, Associate Professor, Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

**Kyle J. Curham**, Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

**Paige Ethridge**, Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

**Spencer Fix**, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland College Park, College Park, MD

**Dan Foti**, Associate Professor, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN

**Philip A. Gable**, Associate Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE

**Lilianne Gloe**, Department of Psychology, College of Social Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

**Benjamin Griffiths**, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, UK

x LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

**Simon Hanslmayr**, Professor, Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging, School for Neuroscience and Psychology, University of Glasgow, UK

**Eddie Harmon-Jones**, Professor, School of Psychological Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

**Jeremy Harper**, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

**Christoph S. Herrmann**, Professor, Experimental Psychology Lab, Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany

**William G. Iacono**, Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

**Florian H. Kasten**, Experimental Psychology Lab, Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany

**Andreas Keil**, Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology and Center for the Study of Emotion & Attention, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

**J. Leon Kenemans**, Professor, Biopsychology and Psychopharmacology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

**Alpár S. Lázár**, Associate Professor, School of Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK

**Zsolt I. Lázár**, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Physics, Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

**Courtney Louis**, Department of Psychology, College of Social Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

**Stephen M. Malone**, Research Assistant Professor and Co-investigator, Minnesota Center for Twin & Family Research, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

**Ali Mazaheri**, Associate Professor, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, UK

**Sebastian Michelmann**, Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Princeton, NJ

**Matthew W. Miller**, Associate Professor, School of Kinesiology, Auburn University, Auburn, AL

**Jason Moser**, Professor, Department of Psychology College of Social Science, Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

**Belel Ait Oumeziane**, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS xi

**J. Matias Palva**, Research Director, Department of Neuroscience and Biomedical Engineering, Aalto University, Helsinki

**Satu Palva**, Professor, Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging, School of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Glasgow, Glasgow

**Taylor Popp**, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA

**John E. Richards**, Professor, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

**Stefanie Russman Block**, Department of Psychology, College of Social Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

**Dennis J. L. G. Schutter**, Professor, Experimental Biopsychology of Motivation and Emotion, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

**Kevin M. Spencer**, Research Health Scientist, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System; and Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

**Daniel Str**ü**ber**, Adjunct Professor, Experimental Psychology Lab, Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany

**Nina Thigpen**, Research Scientist at Google X, The Moonshot Factory, Mountain View, CA.

**Bernadette C. M. Van Wijk**, Marie Curie Research Fellow at the University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

**Bradley Voytek**, Associate Professor, Department of Cognitive Science, UC San Diego, San Diego, CA

**Anna Weinberg**, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

**Wanze Xie**, Assistant Professor, School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China

## [Foreword](#page-5-1)

### Steven J. Luck

When Hans Berger conducted his pioneering human EEG recordings in the 1920s, his first major discovery was the *alpha rhythm*, a 10-Hz oscillation that grew larger when the subject's eyes were closed. A few years later, Lord Adrian (my intellectual great-greatgrandfather) showed that the alpha rhythm also varied according to whether the subject was focusing intensely or daydreaming. Thus the study of EEG oscillations was born.

But this area of research underwent a protracted childhood, because the scientists of the mid-twentieth century could not easily see smaller oscillations amidst the chaotic twists and turns of the scalp EEG. To pull out specific neural processes from the complex and noisy EEG, they began to use signal averaging techniques that can isolate the brain potentials that are triggered by specific events such as the onset of a light (the *event-related potentials* or ERPs). However, these techniques assume that the phase of the signal is constant across trials, and the application of signal averaging to EEG data eliminates or hopelessly distorts oscillating activity. Indeed, for the first 30 years of my own research career, I viewed the alpha rhythm as a nuisance that should be suppressed lest it contaminate my precious ERP waveforms.

All of this began to change in the 1980s and 1990s, partly driven by high-profile studies of local field potential oscillations in animals and partly driven by the application of time-frequency analysis methods to human EEG recordings. The brain oscillations that were obscured by signal averaging could now be visualized and quantified. A new generation of researchers began studying human EEG oscillations and linking them with microelectrode data from animals and computational models of brain dynamics.

In science, the introduction of a new approach often leads to a burst of progress followed by the realization that things are not as simple as they seem. The new wave of oscillation research followed this common path, with the discovery of important new phenomena being accompanied by conceptual and methodological challenges. One such challenge—related to the famous Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle—is that precision in the time-domain is inversely related to precision in the frequency domain. The more precisely you determine the frequency of an oscillation, the less you can say about when the oscillation was present.

A second important challenge is the difficulty of distinguishing between bona fide oscillations and other kinds of neural events. Part of the genius of the Fourier transform xiv Foreword

is that *any* waveform—whether or not it contains oscillations—can be reconstructed by summing together a set of sinusoids. As a result, when you apply a method such as the Fourier transform to a time-domain signal such as the EEG, you will always see activity at some frequencies, whether or not the signal is actually oscillating. And what if the brain is oscillating, but not in a sinusoidal manner? This can lead to completely artifactual results, such as the apparent coupling of the amplitude of one frequency with the phase of another frequency.

A third key challenge is the interpretation of brain oscillations. Virtually any system containing multiple interconnected parts will oscillate when energy is introduced. Those oscillations can be essential to the function of the system, as when the sound of a single violin fills a concert hall or when a clock keeps perfect time. But oscillations can also be a sign of trouble, as when a bridge shakes violently following an earthquake or when a seizure spreads throughout the brain. The fact that the brain oscillates, and that the oscillations vary across states or tasks, does not mean that the oscillations themselves are playing a functional role in the brain's computations. They may be epiphenomenal. Or they may be fundamental. Distinguishing between these possibilities may require invasive recordings in animals or experimental manipulations of oscillations via brain stimulation.

The study of EEG oscillations has reached a key point in its development. The application of time-frequency methods to EEG data is now commonplace, aided by open source data analysis packages such as FieldTrip and EEGLAB. Labs that eschewed these methods for many years—including my own—are now examining oscillations alongside traditional event-related potentials. However, this success means that more researchers are using time-frequency analyses without understanding the challenges involved in properly quantifying and interpreting oscillatory activity. As a result, this edited volume has appeared at the perfect time.

The chapters in this volume will give scientists of all career stages the knowledge they need to understand how oscillations arise in the brain, how they can be accurately quantified, and how they can be appropriately interpreted. I encourage readers to think deeply about the many important issues that are raised in these chapters, especially with regard to the three challenges I have outlined. But if you think deeply and follow the "best practices" described in this volume, you will be able to see brain activity that would otherwise be invisible. And you may make important new discoveries about the human mind and brain.

## [Preface](#page-5-2)

### **Motivation**

The time is ripe for a comprehensive book on the array of historical and cutting-edge frequency and time-frequency approaches to studying EEG/ERP because of the widespread interest in frequency research. There is a great need for a book organizing the diverse and important methods of EEG frequency analyses and interpreting the resultant measures.

One stream of research comes from traditional (band-based) frequency analyses. Likewise, understanding the cutting-edge frequency analyses which may not be familiar to many EEG researchers is increasingly important for investigators applying frequency analyses. However, there is a major need for a comprehensive handbook on analyses within this domain. Although research has been rapidly accumulating over the last decade, there has not been sufficient organization of research on the topic. We believe this comprehensive handbook is increasingly necessary to help delineate the boundaries of the area, the major scientific questions that need to be addressed, and the core theoretical frameworks that can guide future research and development.

Thus, a specific goal of this book is to bring together these various scientific perspectives and research approaches within a single reference volume that provides an integrated, cutting-edge overview of the current state of the field. This volume comprises contributions from leading researchers within various allied disciplines.

The use of electroencephalography (EEG) to study the human mind has seen tremendous growth across a vast array of disciplines due to increased ease of use and affordability of the technology. EEG is a non-invasive measure of electrical brain activity. Typically, researchers investigate the EEG signal using either time-domain (e.g., ERP) analyses or frequency analyses. Several books have examined practicalities of conducting ERP analyses and interpreting various ERP measures. However, a comprehensive book has yet to be developed organizing the numerous ways to process EEG frequency and interpreting frequency measures linked to cognitive, affective, and motor processes.

We (editors Philip, Matt, and Ed) felt a great need for a book organizing the diverse and fascinating methods of EEG frequency analyses and interpreting the resultant measures. Frequency analyses provide unique assessments of neural functioning, neural connectivity, and "resting" neural activity studied by EEG researchers. Further, xvi Preface

frequency-domain measures are reliably associated with cognitive, affective, and motor processes of great interest to neuroscientists and psychological scientists. For example, asymmetrical activation of the frontal cortex as measured by the inverse of alpha-band activity is closely linked with motivation and emotion. In addition, analyses examining the synchrony of EEG frequencies recorded from different scalp locations allow researchers to examine brain connectivity without having to incur the costs of magnetic resonance imaging.

## **ORIGIN**

As EEG frequency researchers, we wanted a resource that introduced the myriad ways in which EEG frequency analyses are being investigated. This volume began while the lead editor, Philip, was on sabbatical and seeking to begin a new chapter in his career. During that time, he visited with Matt Miller and the project quickly developed into a collaborative project. After developing the project more, Matt and Philip brought Ed Bernat on board.

As individual editors, we each had areas of expertise in EEG frequency research, but in developing this volume, we quickly discovered that each of our individual areas of expertise were far different from each other. Three editors were necessary to even try to cover the breadth of EEG frequency research being conducted. In addition, we did not want to create a handbook that focused on EEG frequency research specifically in emotion, cognition, or clinical applications. Instead, we wanted to provide a survey of the breadth of work being conducted with EEG frequency research. Try as we might, we also acknowledge this handbook will inevitably fail to cover everyone's interest across all topics. To that end, we hope to receive feedback from readers so that future editions of this handbook can be expanded to encompass the ever-growing field of EEG frequency research.

Together, the project has been a long labor, but well worth the time and effort to develop the resource. We have been especially excited to work with leading experts in the field as they develop chapters for the volume. We are excited for you as the reader to see what we have gotten to see throughout the editing process: the excitement and development of EEG frequency research across a wide range of fields and programs of research.

## **ORGANIZATION**

To aid in reading the handbook, much thought and structuring has been given to the organization of the chapters. As a whole, the book provides a systematic summary of EEG frequency analyses and applications. Individual chapters give depth to each type Preface xvii

of frequency analysis and interpretation of resultant measures. Chapters are organized into three sections.

The first section of the book is focused on basics of EEG frequency research and linking frequency analyses to other components of EEG research, such as event-related potential (ERP) components and the fundamentals of inference from EEG recording. For the second section, contributors focus on specific EEG frequency components that are commonly studied using traditional frequency bands of activity to study specific psychological processes related to cognition, motivation, and perception. The third section focuses on EEG frequency analyses in special populations and altered states. The fourth section of the handbook concludes with chapters focused on advancing methodology used in EEG frequency research.

The initial chapters in the first section describe methods for collecting EEG data for frequency analyses in humans as well as the basics of electrical activity and assumptions regarding the EEG signal. Following these chapters, contributors consider how the oscillations in the EEG signal may give rise to psychological phenomena, and how ERPs can be decomposed into time-frequency components. The chapters go on to consider the relationships between evoked (ERP-related) and induced EEG activity before shedding light upon frequency analyses of LFPs in non-human primates, which may inform frequency analyses of human EEG. The second section begins with the role of gamma oscillations in cognitive and sensory processing. Then, frontal midline theta, which is often linked to cognitive control, is addressed, followed by the role of alpha and beta oscillations in perception and memory. Next, research on asymmetries in frontal alpha oscillations are linked with motivation, followed by a description of the role of oscillatory activity in sensorimotor function. Moving into the third section of the book, the first chapter in this section focuses on changes in EEG frequency throughout infancy, childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. Next, follows an examination of the ratio of theta to beta power in motivation and attentional control as they relate to normal and abnormal behavior. Then, the characteristics of the oscillations in persons with schizophrenia are described, followed by an examination of how frequency analyses clarify control processes in people with anxiety. The concluding section of the handbook begins with specialized frequency analyses for source localization and brain connectivity before concluding with chapters describing how to manipulate oscillatory activity with brain stimulation and how to parameterize neural field potential data to, for example, tease apart true oscillations from aperiodic signals.

## **LIMITATIONS OF THE CURRENT VOLUME**

As with any book, the current volume is not a complete work on the topic of EEG frequency analyses. In addition, this is not the first book on EEG frequency research. Many xviii Preface

excellent books have been published this topic. Here we mention what the current book does not include and refer the reader to additional resources available in other books.

One of the most inspiring resources for us as editors is Steven J. Luck and Emily S. Kappenman's *Oxford Handbook on Event-Related Potential Components*. This book has been used in our courses and labs, as well as by countless other EEG researchers. It focuses on the excellent work that has investigated the spectrum of ERP components derived from EEG research. We were inspired to build a similar handbook that would cover EEG frequency analyses. The current book does not address ERP research in much detail. The closest chapters addressing ERP research are Chapters 4 and 5. For those desiring a more comprehensive volume on ERP analyses, please see Luck and Kappenman.

Another extraordinary resource is Mike X. Cohen's *Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice*. This book has served as the primary resource for many EEG researchers, including us, to learn how to conduct time-frequency analyses, and to teach our students how to perform the analyses. The book is particularly helpful in guiding the reader from the mathematical bases of frequency analyses to the implementation of these analyses in MATLAB. These analyses are referenced throughout our book and include fast Fourier transforms, complex Morlet wavelet convolution, intertrial phase clustering, surface Laplacian filtering, phase- and power-based connectivity measures, and cross-frequency coupling. Chapters in our book that address these "how-to" topics include Chapters 4, 5, 19, 20, 21, and 23.

Finally, Chapter 1 of this volume describes how to collect EEG data. For readers who which to have greater detail about implementing and collect EEG from human participants, we recommend Dickter and Kieffaber's *EEG Methods for the Psychological Sciences*. This book is an excellent resource for researchers beginning to implement EEG.

# Part I

## [Chapter 1](#page-5-3)

# [INTRODUCTION](#page-5-3)

*Methods for Collecting EEG Data for Frequency Analyses in Humans*

PHILIP A. GABLE AND MATTHEW W. MILLER

### **1.1 Chapter Aims**

This chapter aims to provide a structure for readers to understand the methodology behind collecting EEG (electroencephalography) presented in the subsequent chapters. It is important to first understand the research methods involved in recording EEG frequency before delving into more advanced frequency analyses and the interpretations. As researchers, we focus this first chapter on a brief introduction to the topic of EEG methodology and scientific practices. To begin, however, we feel it is important to lay down definitions for terms used throughout the book.

## **1.2 Definitions of EEG Frequency Research**

EEG refers to the recording of electrical brain activity from the human scalp. It is one of the most common methods for measuring brain functioning in areas of mind, brain, and behavior science. EEG data contain rhythmic activity or waves that may reflect neural oscillations, or fluctuations in the excitability of populations of neurons (more on this later). These rhythmic fluctuations are typically described using two main descriptors. The first is frequency, which is the speed of the wave, and it is measured in hertz (Hz), which is the number of wave cycles per second. The second is power, which is the squared amplitude of the wave. The greater the power of an oscillation, the greater the energy of that oscillation. All of the chapters in this work discuss frequency 4 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

with most referencing power. Sometimes researchers investigate the phase of the wave, which is the position of the wave measured in radians or degrees. Many of the chapters included here discuss phase.

The brain produces rhythms in multiple frequencies, which can be isolated from the raw EEG signal using multiple techniques described by Curhamn & Allen in Chapter 2, and Voytek in Chapter 23). Different psychological processes are linked to different frequencies, which are often grouped into bands. The most commonly studied bands include delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (lower gamma 30–80 Hz; upper gamma 80–150 Hz). While these are not the only frequency bands, these are the bands most typically associated with processes of mind and behavior measured by EEG. Importantly, these bands are not defined without reason, but instead reflect biological changes at the cellular level (see Cohen, 2014 and Buzsaki, 2006 for reviews). However, these bands are not rigid and may vary depending on individual differences, such as brain development, structure, and chemistry. Chapters in the second section of this work note how different frequency bands are associated with cognitive, motivational, and sensorimotor processes.

These definitions are by no means complete. Individual chapters provide more precise definitions of terms used. With this initial framework, readers should be able to venture into subsequent chapters focusing in more detail on these definitions. Because EEG is a rather complex measure, we focus in more detail on the physiological basis and scientific methods used to record and process EEG.

## **1.3 Physiological Basis of EEG**

EEG is measured because all nerve cells communicate using electrical signals, sending information throughout the brain and to the rest of the body. Within a neuron, an action potential is an electrical wave that runs from the axon hillock at the cell body to the axon terminals. At the axon terminals, the action potential causes neurotransmitter to be released. This neurotransmitter crosses the synaptic gap and binds to receptors on the membrane of the postsynaptic cell. Binding to the receptor causes voltage changes by activating ion channels or second messengers that either excite or inhibit the postsynaptic neuron. The summation of this voltage change in the membrane of the dendrites and cell body of the postsynaptic neuron is called a postsynaptic potential. Postsynaptic potentials tend to occur locally, rather than moving down the axon. This allows postsynaptic potentials to summate rather than to cancel, resulting in voltage changes that have larger amplitudes and can be recorded on the cortical surface or at the scalp.

When tens of thousands to millions of neurons are excited or inhibited at the same time, the voltage change outside the cell (extracellular potential) can be recorded at the scalp using EEG, which measures the sum of electrical activity from excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials over this collection of neurons. The activity can only be recorded on the scalp surface because tissue (cerebrospinal fluid, meninges, skull, and INTRODUCTION 5

skin) between the neurons and scalp conducts the electrical signal. In addition, for electrical activity to be projected to the scalp, cellular alignment must be precisely arranged in parallel so that their effects cumulate to project the electrical activity to the scalp (see Curhamn & Allen, Chapter 2; Keil & Thigpen, Chapter 3). Neurons must be arranged so that the cluster of neurons all have dendrites at one pole and axons departing at the opposite pole. This arrangement is called an open field and occurs when neurons are organized in layers. The cortex, cerebellum, and parts of the thalamus tend to have this open field arrangement of neurons resulting from pyramidal cells.

### **1.4 A Dual Nature**

Due to the electrical basis of the EEG signal, EEG has excellent ability to tell us *when* something is happening in the brain. This is called temporal resolution and is one of the greatest strengths of the EEG signal. The EEG signal measures neural activity at the accuracy of milliseconds, which allows for the ongoing measurement of psychological processes as they unfold (Luck, 2014).

However, the EEG signal is limited in its ability to measure *where* something is occurring. This is called spatial resolution and is one of the greatest weaknesses of the EEG signal. Depending on where the source of the EEG signal is generated, the orientation of the open field neurons might not be parallel to the scalp, thus generating EEG signals in multiple directions. In addition, resistors (e.g., the skull) in the tissue between the neurons and scalp can cause the EEG signal to spread out. Because of the volume conduction through the head, as well as the orientation of the pyramidal cells emitting the signal, the spatial location of the signal is difficult to ascertain. As Keil and Thigpen (Chapter 3) note, a difference in frequency power between two experimental conditions could be the result of a different number of neurons activated, the temporal order in which they were activated, or neurons with different orientations being activated. To address EEG's limited spatial resolution, cortical source localization techniques have been developed and are reviewed by Xie and Richards (Chapter 19). In sum, using an analogy from Steve Luck's ERP Boot Camp, the EEG signal is like being able to see every frame of a movie as it unfolds. However, because of the low spatial resolution, the movie appears a bit blurry.

### **1.5 EEG Equipment and Recording**

The earliest method of EEG measurement was implemented by Hans Berger in the late 1920s. In his early experiments, he used two sponges soaked in saline connected to an amplifier (Berger, 1929). While the equipment and processing of EEG signal has advanced considerably since that time, the basic components remain similar. EEG 6 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

electrodes are placed on or near the head, the signal from the electrode is transmitted to an amplifier, and the signal is digitized and recorded.

In psychological research labs, EEG is usually recorded from 32, 64, 128, or more electrodes. In other research (e.g., sleep, nonhuman) fewer electrodes (2–8 electrodes) is more typical. When larger numbers of electrodes are used, electrodes are mounted in an electrode cap or net. When fewer electrodes are used, electrodes may be positioned individually on the head using a bonding agent. Electrodes can either be wet electrodes or dry electrodes. Wet electrodes are made of silver, silver-chloride, or tin, and a conductive gel or liquid is placed inside or around the electrode. Dry electrode systems use electrodes coated in gold, silver, or nickel, and place electrodes directly on the scalp without a conductive medium. Wet electrodes generally have higher signal quality, but dry electrodes may be preferred when high impedance levels are tolerable, or when recording for long periods.

Electrode systems will have active or passive electrodes. Active electrodes contain a small pre-amplification unit directly attached to the conductive metal in the electrode. This allows the EEG signal picked up at the sensor to be immediately amplified before additional environmental noise can be introduced. Passive electrodes do not have amplification at the electrode, and instead carry the signal to an amplifier about a meter away. Compared to passive electrodes, active electrodes minimize noise introduced during signal transmission, tolerate high impedance recording, and reduce participant preparation time. Passive electrodes have a lower profile to benefit transcranial magnetic stimulation over the cap and can be used inside an MRI bore.

Electrode placement is predominantly based on the 10–20 system (Jasper, 1958). Electrodes are named using the first letter to refer to the brain region under the electrode from anterior to posterior (e.g., Fp—frontal pole, F—frontal, C—central, P—parietal, T—temporal, O—occipital). Numbers following the letter are used to indicate the lateral position of the electrodes. Ascending odd numbers indicate sites more lateral over the left hemisphere of the brain, whereas ascending even numbers indicate sites more lateral over the right hemisphere of the brain. The letter Z is used to designate medial sites. In addition to the recording electrodes, EEG also requires a ground electrode, which assists in reducing electrical noise, as well as a reference electrode placed on the head or face.

The raw EEG signal is usually filtered during recording. Signals below 0.1 Hz or above 200 Hz are removed because the frequency bands of interest fall within this range. A filter at 60 Hz (in North and South America) or 50 Hz (in Europe, Asia, and Africa) may also be used to further reduce electrical noise from alternating current.

### **1.6 Artifacts**

The quality of the EEG is crucial to EEG frequency analysis. To best record EEG signal reflecting brain activity, researchers must remove signal that occurs because of anything other than neural activity. Signal that is not naturally present is called artifact. These INTRODUCTION 7

can be biological (e.g., muscle movement) or nonbiological (e.g., electrical noise). Much artifact can by eliminated by taking preventative measures. Artifact that cannot be prevented should be removed.

Muscle artifact, or electromyography (EMG), is one of the most common types of artifacts and is usually high in frequency (100–500 Hz). Usually, this falls outside of the frequency range typically investigated by researchers. However, some muscle artifact may seep into lower frequencies. Researchers can reduce muscle artifact by instructing participants to limit their muscle movements. Muscle artifact that does occur can be removed through visual inspection, filtering, and automatic artifact detection algorithm. It should be noted that some muscle artifact may be related to the experiment (e.g., sensorimotor studies). In such cases, it may be beneficial to measure EMG at the site movement is expected (e.g., the hand), then control for it in analyses.

Eye movements are another common type of artifact. The eyeball is polarized which causes large artifact in the form of voltage changes resulting from moving the eyes. Like dealing with muscle artifact, eye movement artifact can be removed from signal using recordings near the eyes called electro-oculograms (EOG). One pair of EOG electrodes are placed above and below the eye, while another pair is placed just lateral to either eye on the temple. Eye blinks also create eye movement artifact. It is preferable to correct blink artifact using an artifact reduction algorithm based on regression, principal component analyses, or independent component analyses.

Artifacts occurring in the environment are the result of nonbiological factors. The most common sources of these artifacts are the result of external electrical noise coming from compact fluorescent lightbulbs, data hubs, or electrical junctions. Grounding will aid in reducing these sources of noise, as will electromagnetically shielded rooms.

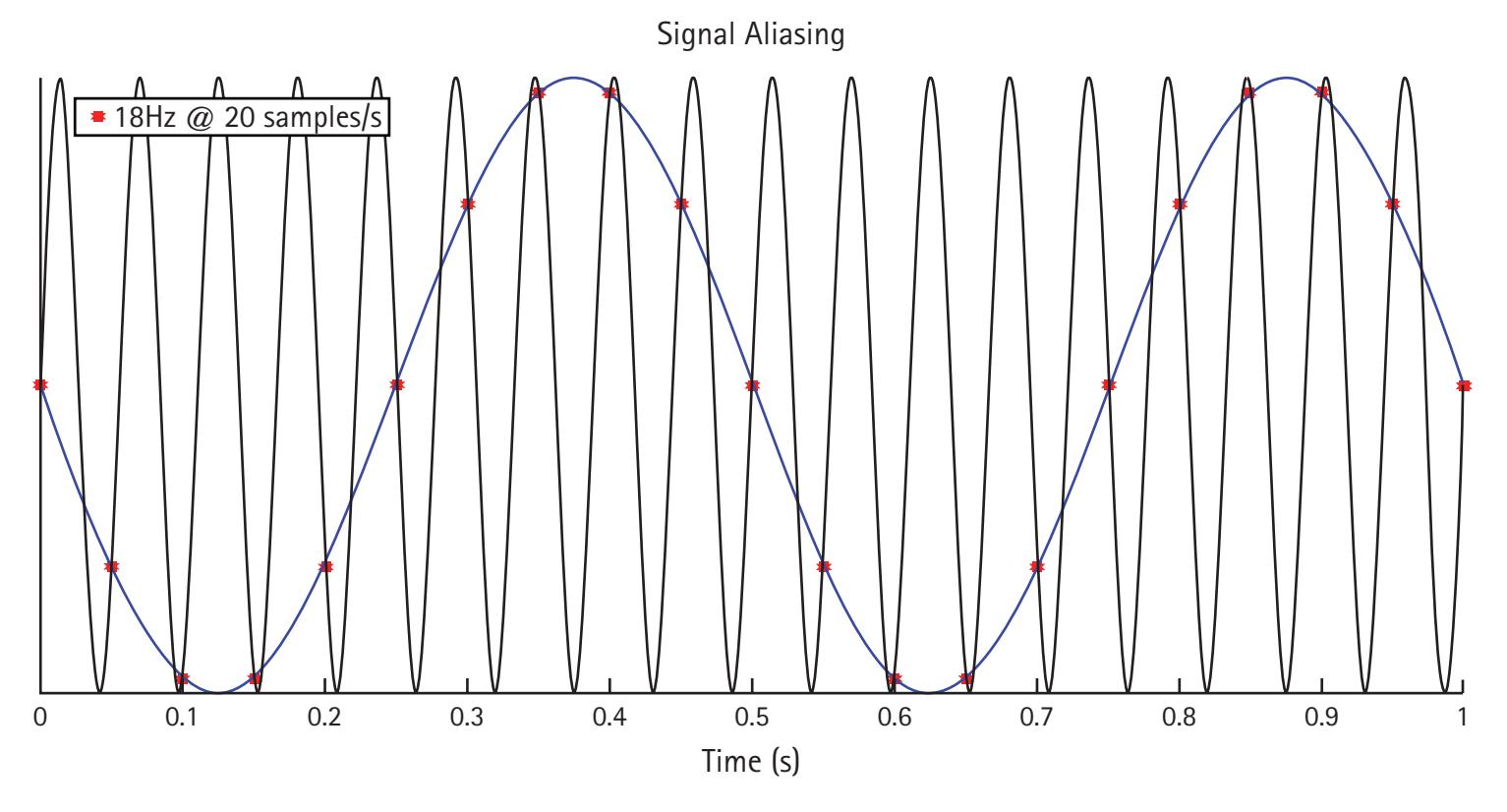

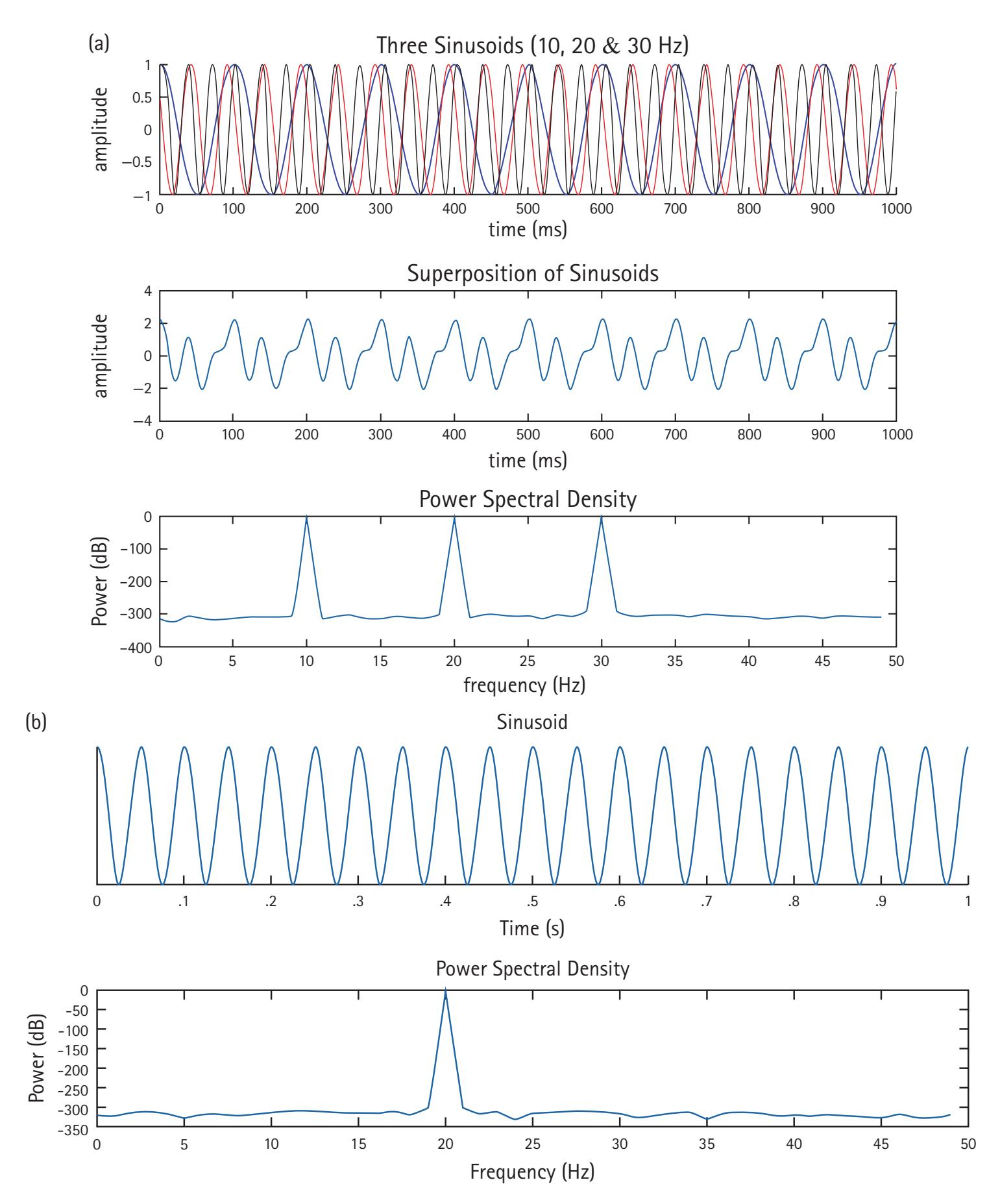

### **1.7 Frequency Processing**

Once an EEG signal is recorded, the raw data must go through several processing steps before it is in a format useable in analyses. The raw signal is collected in the time-domain but must be converted into a frequency-domain representation. One way this can be accomplished is in the form of a power spectrum, which collapses frequency data across time to map the frequencies present. A frequency analysis can be conducted over windows that are minutes, seconds, or milliseconds in length; these are called epochs. Epochs that are seconds or minutes can be analyzed for power spectra using a Fourier transform, which decomposes a signal into a series of sine and cosine functions of various frequencies. The function of each frequency begins with its own phase. A Fourier transformation assumes that the epoch repeats infinitely forward and infinitely backward in time. A process called windowing is used to prevent artifact created from the Fourier transform. However, windowing can also introduce artifact and data loss into the frequency analysis. Overlapping epochs is a way to prevent discontinuity, data loss near the ends of the epoch, and to help meet the assumptions of the Fourier transform in windowing.

8 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

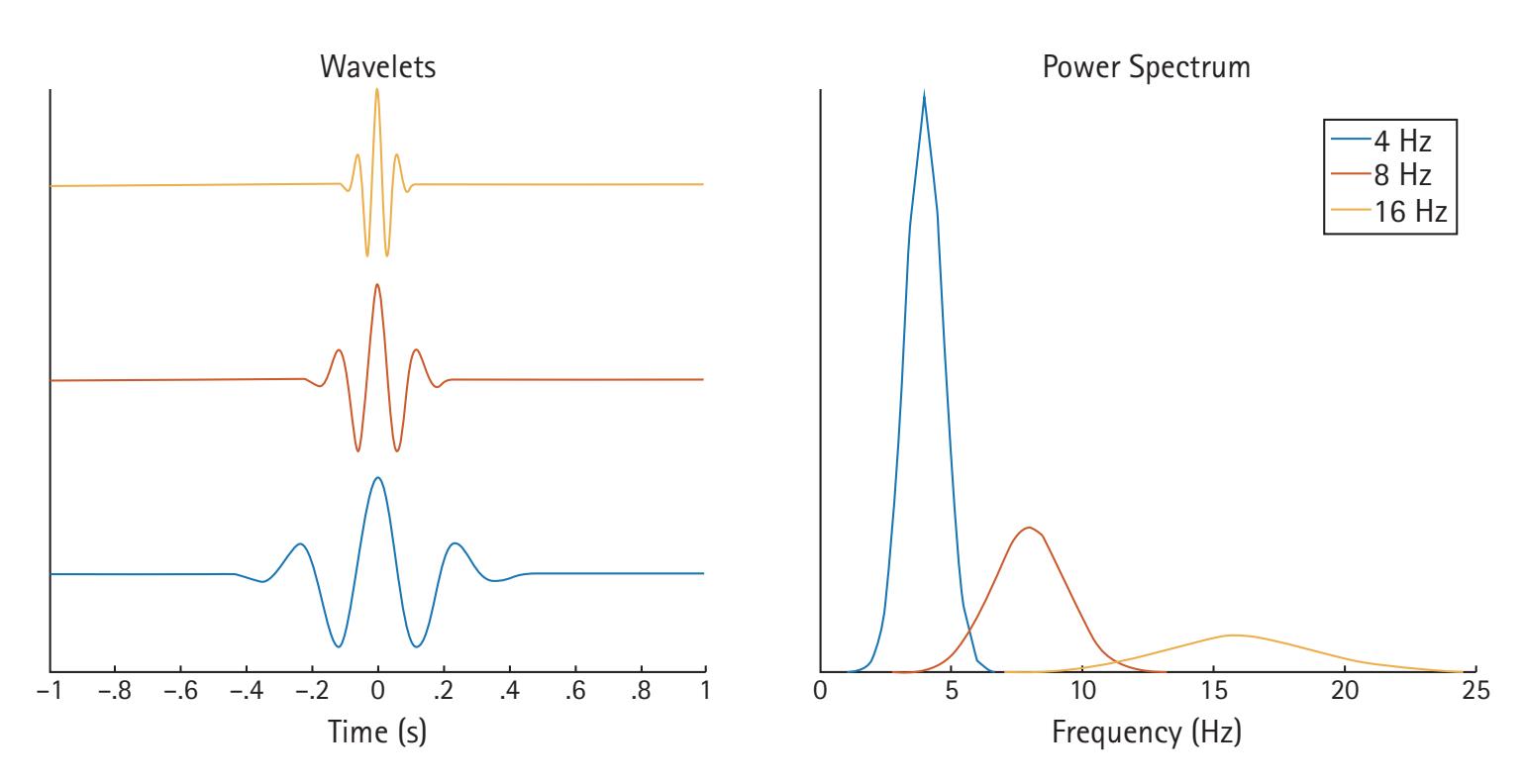

One of the most common forms of signal frequency processing is to use a fast Fourier transform (FFT). An FFT provides the spectrum of frequency power for a period, which is often averaged across a range of frequencies comprising a band (e.g., theta). It also provides a spectrum of phase. The power spectrum reflects the energy of each frequency determined by the squared amplitude of the wave. The phase spectrum reflects the phase in radians or degrees of the sine or cosine wave at each interval (e.g., 1/T). Most frequency analyses focus exclusively on frequency power. However, there is increasing interest in examining the phase of frequencies (e.g., see Michelmann, Griffiths, & Hanslmayr, Chapter 10; Palva & Palva, Chapter 20). Crucially, the FFT has two limitations: it poorly depicts changes in the frequency spectrum over time, and it assumes the EEG data are stationary during the period to which the FFT is applied. To overcome these limitations, time-resolved frequency decomposition techniques are growing in popularity, particularly wavelet analyses (e.g., complex Morlet wavelets), which reveal changes in power at various frequencies with excellent temporal precision (see Aviyente, Chapter 4; Weinberg, Ethridge, Oumeziane, & Foti, Chapter 5).

### **1.8 Experimental Design**

Regardless of the EEG recording and processing, researchers need to be considerate of experimental design. In any experiment, researchers should manipulate a single variable at a time to ensure internal reliability, but this procedure is challenging in EEG research. This follows because manipulating one variable between conditions may inadvertently change a second variable between conditions that affects EEG. For example, if an experimental condition attempts to manipulate participants' motivation while they are physically responding to stimuli, then EEG linked to motivation may change (see Harmon-Jones, Popp, & Gable, Chapter 11) but so may the vigor of their responses and EEG linked to sensorimotor function (see van Wijk, Chapter 12). Thus, it is crucial that researchers attempt to experimentally control for such factors in their experimental design or statistically account for them by collecting covariates, such as EMG to index the vigor of motor responses.

#### **1.8.1 Reproducibility in Electrophysiology: Challenges and Recommendations**

A scientific discipline benefits from reproducible results because they strengthen confidence that they reflect the way a system operates under certain conditions.1

1 There have been special issues in the *International Journal of Psychophysiology* and *Psychophysiology* devoted to reproducibility and, relatedly, open science in cognitive electrophysiology, and readers are encouraged to read these special issues (Kappenman & Keil, 2017; Larson & Moser, 2017).

INTRODUCTION 9

We use Goodman, Fanelli, and Ioannidis's (2016) definition of reproducible results as "obtaining the same results from the conduct of an independent study whose procedures are as closely matched to the original experiment as possible" (pp. 2–3). Although there are different definitions of what it means to obtain "the same results" (Open Science Collaboration, 2015), we hope that closely matched studies yield effects with confidence intervals that overlap substantially (for details on using confidence intervals in EEG studies, see Groppe [2017]), thus allowing us to make precise inferences about the true size of the effect being studied. Since reproducible results are crucial for a discipline, it is important to consider what can be done to obtain them. We discuss several research practices that increase the likelihood that an original result will be reproducible and that subsequent studies reproduce the original result, as well as challenges faced by cognitive electrophysiology researchers attempting to do so.

### **1.9 Pre-Register Specific Hypotheses**

Each study should test specific hypotheses because results that confirm hypotheses are more likely to be true than results based on exploratory analyses (Ioannidis, 2005). Thus, it is crucial that researchers do not rewrite their hypotheses to fit with their results, a practice known as HARKing (hypothesizing after results are known), as it exaggerates the confidence the reader has that the results are true. One method to avoid HARKing is pre-registering hypotheses using the Open Science Framework (osf.io), aspredicted. org, or other repositories. However, formulating specific hypotheses for cognitive electrophysiology studies can be difficult, especially if researchers want to frame them statistically. For example, a researcher may be confident in predicting that an experimental condition will affect EEG activity, but they may struggle to define "EEG activity" as a dependent variable. In ERP studies, this is less of a concern because the dependent variables (ERP components) are well-characterized (Kappenman & Luck, 2012); however, there are fewer well-characterized time-frequency variables. Although researchers can be vague about defining their time-frequency variables, they should then use statistical analyses with strict corrections for multiple comparisons (see Cohen, 2014). This reduces the likelihood of making Type I errors, but consequently increases the likelihood of making Type II errors. (Researchers may also consider data-driven region-ofinterest approaches; see Brooks et al., 2017). Therefore, time-frequency analyses will benefit from having well-defined dependent variables (Indeed, this was an initial impetus for this book!).

For example, if a researcher believes an experimental manipulation is likely to influence EEG activity related to cognitive control, they can have a clearly defined dependent variable of oscillatory activity in the theta frequency bandwidth measured from frontal midline electrodes over a certain time (Cavanagh & Cohen, Chapter 9). In a pre-registration, researchers should use a more precise definition of their dependent variable than "frontal 10 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

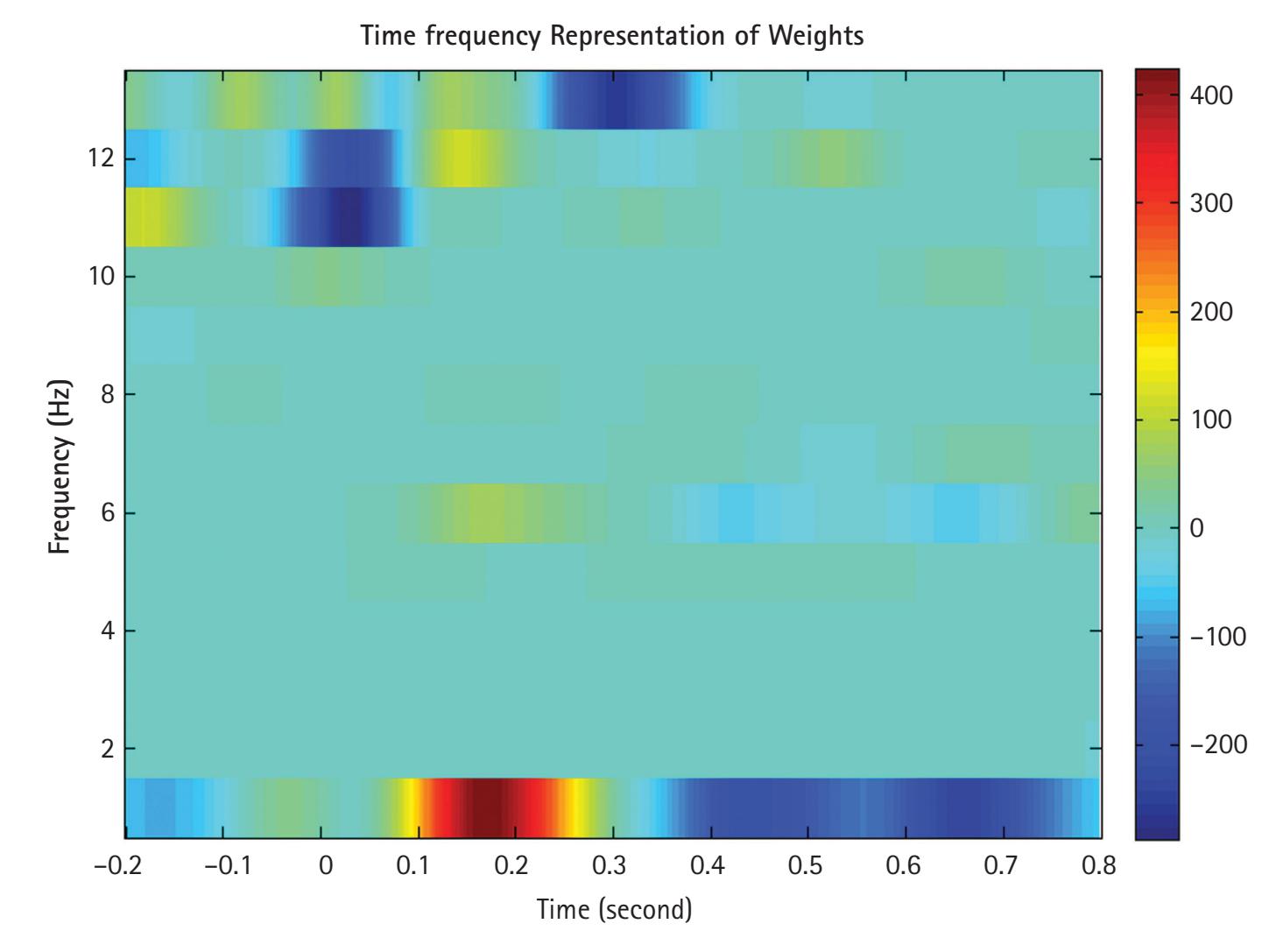

midline theta". For example, they could specify that they will determine the wavelet of 4– 8 Hz that exhibits the greatest peak power between 200 and 600 ms after stimulus onset at electrode Fz for each participant, and then compute the average power of this wavelet during the 200–600 ms time epoch at Fz. They could also introduce some flexibility into the specification of the dependent variable by noting that they will choose a different bandwidth, epoch, and/or electrode if the grand average time-frequency plot (averaged across all conditions) reveals an unexpected time-frequency and/or scalp distribution. In this example, the average across all conditions avoids biasing the analysis in favor of choosing a time-frequency window exhibiting differences between conditions. Besides reducing HARKing and facilitating the specification of dependent variables, pre-registration is crucial for holding researchers accountable to their research design, statistical analyses, and sample size; however, none of these positive features of pre-registration work if researchers deviate from their pre-registration without properly noting the deviation (Claesen et al., 2019).

## **1.10 Increase Power and Conduct A Priori Power Calculations**

Another way that researchers can increase the likelihood that study results are reproducible is by increasing the power of their studies (Ioannidis, 2005). Alarmingly, Button and colleagues' (2013) analysis of neuroscience studies found their average power was very low (8–31%). There are two general ways that researchers can increase the power of their studies. First, researchers should attempt to maximize the effect they are studying and minimize its variance (i.e., increase the standardized effect size). This can be done by using strong experimental manipulations and reliable dependent variables, such as those discussed in this work. Additionally, researchers should increase the signal to noise ratio in their studies by optimizing the number of trials and collecting good EEG data (Cohen, 2017; Luck, 2014).2 Further, when possible, researchers should use within-subjects designs, which is already the case in many cognitive electrophysiology studies. Second, researchers should collect larger samples, which is particularly important when testing between-subjects effects or within-between subject interaction effects. Cognitive electrophysiology studies can require a lot of time to collect and process data, so collecting more participants may seem burdensome, especially for researchers investigating small–medium effects. For example, a two-tailed

2 A good way for researchers to benefit the field (and their citation count) may be for them to establish the number of trials required for different time-frequency variables in different paradigms, which has been done for ERP variables (e.g., Rietdijk et al., 2014). It is worth noting that simply adding more trials may not increase the signal to noise ratio, since participants may fidget more toward the end of long data collections, consequently increasing noise.

INTRODUCTION 11

dependent *t*-test for an effect size of *dz* = 0.35, an alpha = .05, and power = .90 requires 88 participants, according to G\*Power 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., 2009). Indeed, it is likely that researchers will often find themselves studying small-medium effects. Specifically, when researchers conduct a priori power calculations to determine their sample sizes, they should assume that the effect sizes in the extant literature are inflated, due to publication bias by researchers and journals (i.e., only publishing significant results) (for a more detailed discussion on sample size calculations in EEG studies, see Larson & Carbine, 2017). Although it is difficult to collect and process large samples, it is crucial to the reproducibility of cognitive electrophysiology studies. To reduce the demands large sample sizes impose, researchers who mentor doctoral students, review for and sit on the editorial boards of journals, are involved in hiring decisions about faculty and post-doctoral researchers, and are involved in promotion and tenure decisions should reconsider expectations about the speed of science and the number of publications (for further discussion on these issues, see Bradley (2017) and Yeung [2019]). Also, if a researcher is concerned about allocating a lot of time to a study that may not yield significant results, they can conduct a sequential analysis where they pause data collection after a pre-specified sample has been collected and then determine whether to continue data collection based on if the incremental results are significant (given an adjusted alpha level) and if the incremental results suggest an effect size that is too small to be of interest (Lakens, 2014).

## **1.11 Make Methods, Materials, and Data Open**

In addition to pre-registered hypotheses and adequately powered studies, researchers should also make their methods, materials, and data accessible3 . In so doing, they will allow other researchers to "methodologically reproduce" the original study (Goodman et al., 2016), which should increase the likelihood of observing the same results. Researchers should make their stimuli and stimulus presentation scripts available and include specific details about instructions given to participants and the equipment used for the study. Further, researchers should also make signal and statistical processing scripts available and provide their data when possible so that other researchers can attempt to reproduce analyses or explore new ones. There are various ways to provide this information, including on the Open Science Framework and GitHub (github.com).

3 There is a special issue in the *International Journal of Psychophysiology* devoted to open science in human electrophysiology, and readers are encouraged to read it (Clayson, Keil, & Larson, 2022).

12 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

### **1.12 Replicate and Expand**

The recommendations were made to increase the likelihood that researchers' original results will be reproducible, but the recommendations also apply to researchers attempting to reproduce original results. Crucially, researchers attempting to reproduce original results should also attempt to replicate and expand an original finding (Cohen, 2017), preferably increasing the sample size by two and half times the original (Simonsohn, 2015). Specifically, cognitive electrophysiology will benefit if most studies include an attempt to reproduce an original result and then add a new result (e.g., by adding a new experimental condition). With results from replication attempts, more precise estimates about the direction and size of effects can be made. Of course, it is nearly impossible to reproduce a study methodologically. For example, different researchers may have different criteria for manually rejecting trials, and different independent component analyses may yield different components. However, researchers can still come quite close to a methodological reproduction, especially if methods and materials are available for them to use. A challenge for cognitive electrophysiologists is that they often employ different signal processing methods, such as subtracting or not subtracting the ERP from an epoch of EEG data prior to convolving the data with a wavelet. To this end, researchers should use the same methods as the original study, unless a different method is clearly superior. Of course, whether a different method is clearly superior is debatable; thus it is incumbent upon the researcher conducting the methodological reproduction to state their case in a compelling way.

### **1.13 Explore**

Some of the most exciting and reproducible effects in cognitive electrophysiology have been discovered by accident (e.g., Kutas & Federmeier, 2011), meaning that they would not have occurred if researchers had only conducted confirmatory research testing a priori hypotheses. Thus, it is imperative that researchers conduct exploratory analyses in addition to confirmatory analyses. However, results from exploratory analyses should be clearly labeled as such to avoid misleading readers to having excessive confidence in the result. Ideally, then, a study will test pre-registered confirmatory hypotheses that replicate and expand an original result and conduct exploratory analyses. Compelling results from the exploratory analyses can then serve as a priori hypotheses in future confirmatory research. Finally, some of the most exciting exploratory research may come from analyzing old data in new ways. For example, Voytek (Chapter 23) proposes exciting new analytical methods that researchers can apply; his signal processing scripts are freely available [\(https://voyteklab.com/code\)](https://voyteklab.com/code), and researchers can use these scripts to analyze their old data or other openly available data.

INTRODUCTION 13

### **References**

- Berger, H. (1929). Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. *Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten*, *87*, 527–570. [https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01797193.](https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01797193)

- Bradley, M. M. (2017). The science pendulum: from programmatic to incremental—and back? *Psychophysiology*, *54*, 6–11. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12608

- Brooks, J. L., Zoumpoulaki, A., & Bowman, H. (2017). Data-driven region-of-interest selection without inflating Type I error rate. *Psychophysiology*, *54*, 100–113. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12682

- Buzsáki, G. (2006). *Rhythms of the brain*. Oxford University Press.

- Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. *Nature Reviews Neuroscience*, *14*, 365–376. doi:10.1038/nrn3475

- Claesen, A., Gomes, S., Tuerlinckx, F., & Vanpaemel, W. (2019). Comparing dream to reality: An assessment of adherence of the first generation of preregistered studies. *PsyArXiv* [online].

- Clayson, P. E., Keil, A., & Larson, M. J. (2022). Open science in human electrophysiology. *International Journal of Psychophysiology*, *174*, 43–46. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsy](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2022.02.002) [cho.2022.02.002](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2022.02.002)

- Cohen, M. X. (2014). *Analyzing neural time series data: Theory and practice*. MIT Press.

- Cohen, M. X. (2017). Rigor and replication in time-frequency analyses of cognitive electrophysiology data. *International Journal of Psychophysiology*, *111*, 80–87. doi: 10.1016/ j.ijpsycho.2016.02.001

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G\*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. *Behavior Research Methods*, *41*, 1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Goodman, S. N., Fanelli, D., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2016). What does research reproducibility mean? *Science Translational Medicine*, *8*, 341ps12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5027

- Groppe, D. M. (2017). Combatting the scientific decline effect with confidence (intervals). *Psychophysiology*, *54*, 139–145. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12616

- Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. *PLoS Medicine*, *2*, e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

- Jasper, H. H. (1958). The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. *Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology*, *10*, 371–375.

- Kappenman, E. S., & Keil, A. (2017). Introduction to the special issue on recentering science: Replication, robustness, and reproducibility in psychophysiology. *Psychophysiology*, *54*, 3–5. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12787

- Kappenman, E. S., & Luck, S. J. (Eds.) (2012). *The Oxford handbook of event-related potential components*. Oxford University Press.

- Kutas, M. & Federmeier, K. D. (2011). Thirty years and counting: Finding meaning in the N400 component of the event-related brain potential (ERP). *Annual Review of Psychology*, *62*, 621– 647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123

- Lakens, D. (2014). Performing high-powered studies efficiently with sequential analyses. *European Journal of Social Psychology*, *44*, 701–710. doi: 10.10002/ejsp.2023

- Larson, M. J. & Carbine, K. A. (2017). Sample size calculations in human electrophysiology (EEG and ERP) studies: A systematic review and recommendations for increased rigor. *International Journal of Psychophysiology*, *111*, 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.06.015

14 PHILIP A. GABLE and MATTHEW W. MILLER

- Larson, M. J. & Moser, J. S. (2017). Rigor and replication: Toward improved best practices in human electrophysiology research. *International Journal of Psychophysiology*, *111*, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.12.001

- Luck, S. J. (2014). *An introduction to the event-related potential technique* (2nd ed.). MIT Press. Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. *Science*, *349*, aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716

- Rietdijk, W. J., Franken, I. H., & Thurik, A. R. (2014). Internal consistency of event-related potentials associated with cognitive control: N2/P3 and ERN/Pe. *PLoS One*, *17*, e102672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102672

- Simonsohn, U. (2015). Small telescopes: detectability and the evaluation of replication results. *Psychological Science*, *26*, 559–569.

- Yeung, N. (2019). Forcing PhD students to publish is bad for science. *Nature Human Behaviour*, *3*, 1036. doi: 10.1038/s41562-019-0685-4

# [CHAPTER 2](#page-5-4)

# [LO GIC BEHIND EEG](#page-5-4) [FREQUENCY ANALYSIS](#page-5-4)

*Basic Electricity and Assumptions*

KYLE J. CURHAM AND JOHN J. B. ALLEN

### **2.1 Introduction**

The brain is an electrochemical machine. Although nerve cells differ greatly in their size and morphology, all pass messages using electrical signals, sending information throughout the brain and to the rest of the body via the spinal cord. Within any neuron, an action potential is a wave of electrical activity that travels along the nerve membrane. Action potentials are triggered by the summation of input from other neurons using chemical neurotransmitters, which create voltage potential changes in the post-synaptic neuron. Surface-recorded EEG is blind to the activity of single neurons but can noninvasively measure the electrical activity resulting from summated excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials over millions of these signals in humans. EEG has excellent temporal resolution, but poor spatial resolution; it can tell us *when* something is happening in the brain, but not precisely *where* it is happening.

EEG gives an incomplete picture of the electrical activity occurring in the brain. The cortex is the outermost layer of the brain, and the primary generator of the electrical activity we measure with EEG. Our ability to detect cortical activity largely depends on the parallel arrangement of cortical pyramidal neurons. When millions of parallel neurons fire simultaneously, their electrical activity adds together to generate a signal large enough to detect at the scalp. However, when neural populations fire incoherently, or when they are not arranged in a parallel formation, the electrical activity does not add constructively, so there is no observed signal at the scalp. This chapter introduces basic concepts in electricity in signal processing, with some practical considerations for data collection and analysis, to help readers understand EEG measurement and interpretation.

16 KYLE J. CURHAM and JOHN J. B. ALLEN

## **2.2 Electricity—Voltage, Current, and Resistance**

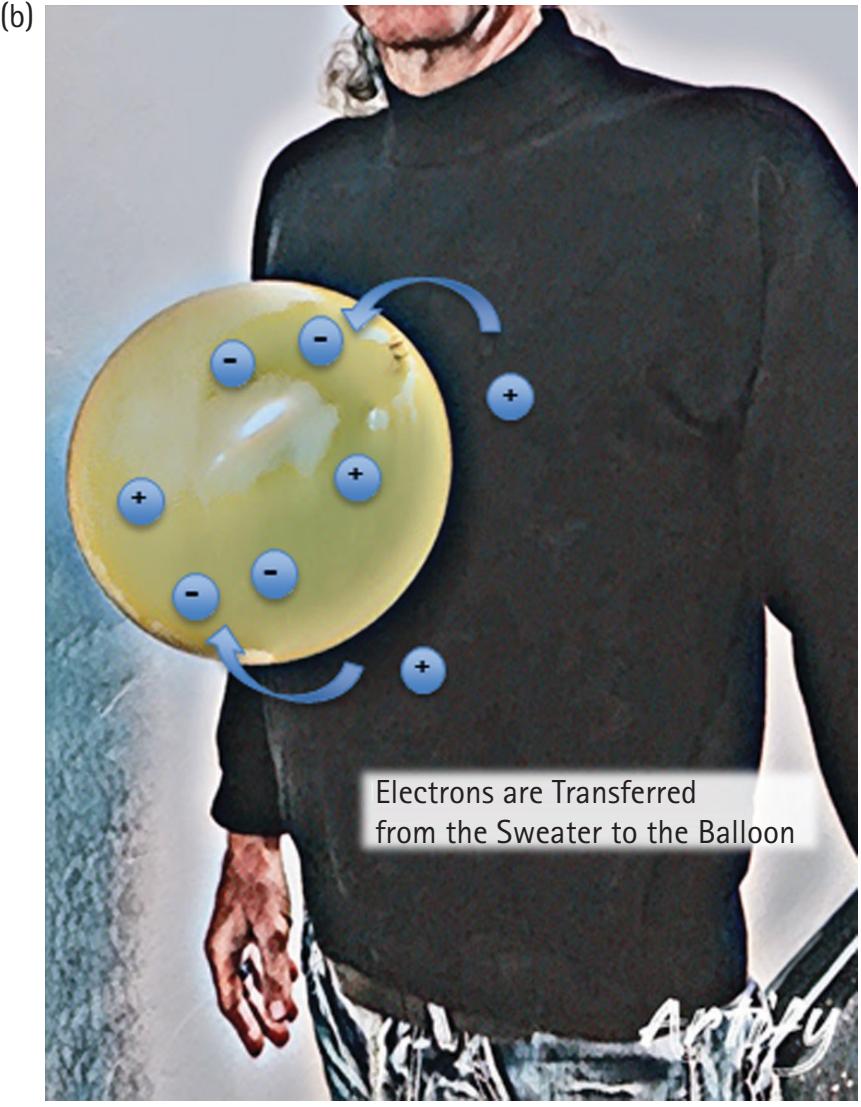

Every physical thing is made up of atoms, which in turn are made up of fundamental particles including protons, neutrons, and electrons. Protons have a positive charge, neutrons have a neutral charge, and electrons have a negative charge. Charges of the same sign repel, and opposite charges attract. A few simple experiments demonstrate the existence of electrical charge. For example, rubbing a balloon on a wool sweater makes the balloon negatively charged as electrons move from the wool to the balloon (Figure 2.1). The degree of attraction or repulsion between two point charges is proportional to the product of the charges divided by the inverse squared distance between them. Therefore, when the electron-rich balloon is brought into proximity of the electronpoor wool, or any neutral surface such as a piece of paper or the wall, the balloon will be attracted. If you subsequently rub a second balloon in the same way, the two balloons will repel each other since they are both negatively charged.

Most of the time, atoms have equal numbers of protons and electrons. However, atoms can become *ionized* when electrons are removed or added, resulting in a net charge. *Electricity* is the phenomenon that describes the behavior and movement of charge. In general, it doesn't matter whether it is the electrons or ions that are moving. The flow of charge can be accomplished either by the transfer of electrons from atom to atom, or, in the case of electrophysiology, by the diffusion of charged ions across cellular membranes.

The degree to which electrons are free to move from atom to atom varies by material type. For example, in metals, the outermost electrons are so loosely bound that they freely move in the space between atoms at room temperature. Because these unbound electrons are free to travel from atom to atom, they are called *free electrons*. The relative mobility of electrons within a material is known as electrical *conductivity*. Conductivity is determined by the types of atoms in a material, and how the atoms are linked together with one another. Materials with few or no free electrons are called *insulators*, and materials with many free electrons are called *conductors*. The directed motion of electrons is called electrical *current*. Just like water flowing through a pipe, electrons move within the empty space between atoms. Under normal conditions, the motion of free electrons in a conductor is random, with no particular direction or speed. However, electrons can be influenced to move in a coordinated fashion through a conductive material by supplying a *voltage*. Voltage is the "pressure" that pushes on free electrons to cause them to flow. The ability of a current to flow from one location to another depends on the *resistance*. In insulating materials, such as glass or rubber, electrons have little freedom to move from atom to atom. The less freedom electrons have to move from atom to atom, the greater the resistance to the flow of charge. A conductor's resistance generally increases as its length increases or its diameter decreases. It is again useful to refer to the water analogy: water can flow more easily through a short, wide pipe than a long, narrow pipe. The international system of units (SI) of current is called the *ampere*.

LOGIC BEHIND EEG FREQUENCY ANALYSIS 17

**Figure 2.1** Before rubbing the balloon against the sweater (A), no net accumulation of electrons exists on the balloon. After rubbing the balloon on the sweater (B), the balloon has accumulated an excess of electrons, and the resultant negative charge of the balloon and positive charge of the sweater creates a force of attraction sufficient to keep the balloon from being pulled to the ground by gravity.

Figure credit: K. Ehrmann.

18 KYLE J. CURHAM and JOHN J. B. ALLEN

| Symbol | Term | Definition | Unit |

|--------|-------------|-----------------------------------------------------------|---------------------|

| E | Voltage | Electromotive force | Volts (V) |

| I | Current | Rate of flow | Amperes (A) |

| R | Resistance | Opposition to current | Ohm (Ω) |

| C | Capacitance | Ratio of the change in charge

to the change in voltage | Farad (F) |

| P | Power | Rate of work | Watt (w) |

| W | Energy | Ability to do work | Watt-second (Joule) |

One ampere is defined as one coulomb of charge (or 6 × 1018 electrons) flowing past a given point in a conductor in one second. The *volt* is the unit of pressure, that is, the amount of *electromotive force* (EMF) required to push a current of one ampere through a conductor with a resistance of one ohm, or 1 volt/ampere.

When resistance is high, electrons tend to gather on one side of the insulating material and the positive ions tend to gather on the other, effectively storing *potential energy* in an *electric field*. At some point, the voltage across the material will exceed a threshold known as the dielectric constant, at which point current begins to flow. This tendency for high resistance to result in charge separation is known as *capacitance*. The amount of charge stored in the capacitor is directly proportional to the surface area of the dielectric (the electrical insulator polarized by the electric field) (Table 2.1).

### **2.3 Circuits**

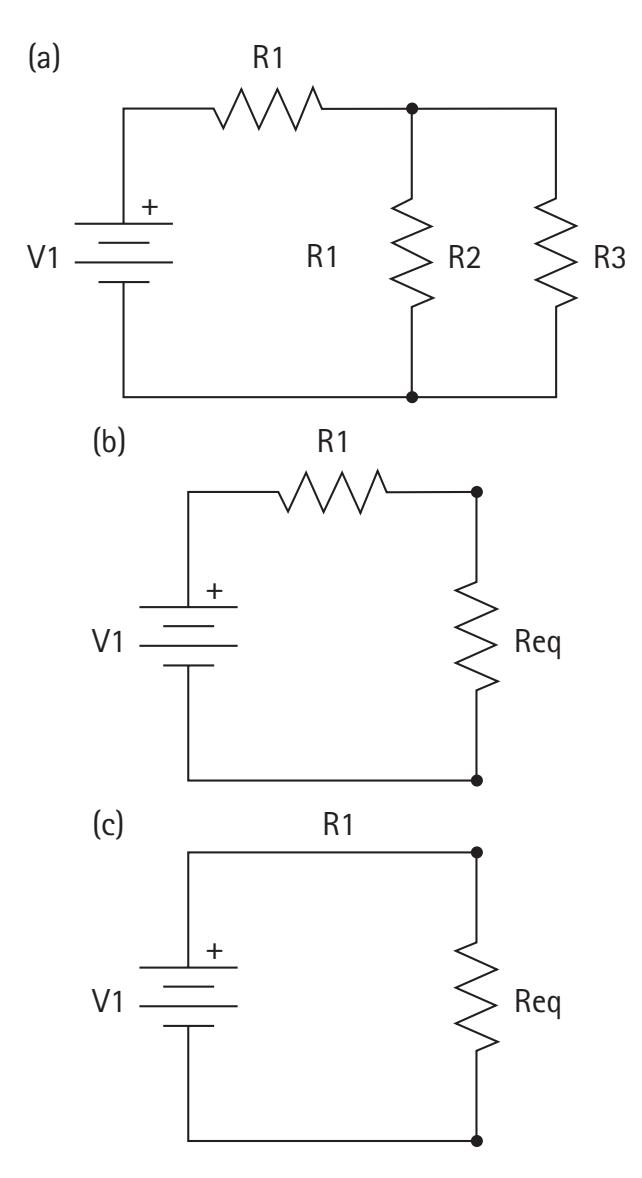

An electrical circuit consists of closed conductive paths between circuit elements. Elements may consist of resistors, capacitors, voltage sources, or current sources. Electrical components may be wired in series or parallel with each other (Figure 2.2). In many cases, circuits consist of some complex combination of series and parallel components. However, these circuits may often be represented by simpler equivalent circuits with identical electrical properties.

To gather some intuition for the flow of current in simple circuits, we refer back to the water analogy. The resistance increases as the pipe gets longer. This is equivalent to stringing together multiple resistors in series. The rule to combine resistors in series is additive:

$$R_{series} = R_1 + R_2 + \ldots + R_n$$

LOGIC BEHIND EEG FREQUENCY ANALYSIS 19

**Figure 2.2** Simple series (left) and parallel (right) circuits. Circuit components labeled with R indicate resistors. Circuit components labeled with V indicate voltage sources.

Conversely, adding multiple resistors in parallel will decrease the overall resistance:

$$\frac{1}{R_{parallel}} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \dots + \frac{1}{R_n}$$

As more "pipes" are added, the water has more paths to escape, decreasing the overall resistance to flow. Capacitors wired in series or parallel follow the same rules, but reversed:

$$\frac{1}{C_{series}} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \dots + \frac{1}{C_n}$$

$$C_{parallel} = C_1 + C_2 + \ldots + C_n$$

Most circuits are some complex combination of series and parallel. We can approach these circuits one piece at a time, deriving a new equivalent circuit at each step (Figure 2.3).

The next few sections explore examples of equivalent circuit representations, and we use equivalent circuit representations to learn the voltages and currents at every point in the original complex circuit. We later show how models of neurons can be represented as a simple equivalent circuit of capacitors, resistors, and voltage sources.

20 KYLE J. CURHAM and JOHN J. B. ALLEN

**Figure 2.3** Reducing a complex circuit (left) to a simple equivalent circuit (right). In an intermediate step, we combine parallel resistors 2 and 3 (middle). Next, we combine resistor 1 with the equivalent resistor from the intermediate step.

### **2.4 Direct current**

Circuits come in two basic flavors: direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC). The difference depends on whether the voltage and current change directions over time. DC circuits maintain currents flowing in a constant direction within a closed loop, whereas AC circuits have current that repeatedly reverses direction. A DC electric source feeds from one terminal to a set of circuit elements and then back to the other terminal, in a complete circuit. Figures 2.2 and 2.3 are both DC circuits due to their constant voltage power source. Note some resistors are connected in parallel, while others are connected in series. At each step, we can combine resistors according to the rules in Section 2.3 to derive a simpler equivalent circuit.

Some circuits may contain both resistors and capacitors. These are known as RC circuits. In a simple circuit with one resistor and one capacitor in series, the capacitor must discharge through the resistor. This discharge occurs at an exponential rate determined by the *RC time constant*. The time constant indicates the number of seconds for the capacitor to become 63.2% charged, or, equivalently, the time for current flow LOGIC BEHIND EEG FREQUENCY ANALYSIS 21

to have slowed by 63.2% from its starting value. This choice of time constant has an intuitive explanation: at any moment in time, the rate of change in voltage is equal to the voltage divided the time constant. For example, a 1 mF cap and a 1 kΩ resistor yields a time constant of one second. If the capacitor is charged to 5 volts, the voltage will fall at a rate of 5 V/s. If the capacitor is charged to 2 volts, the voltage will fall at a rate of 2 V/s.

### **2.5 Alternating Current**

In contrast to DC signals, some sources of electricity produce AC, where voltages and currents periodically reverse direction and switch back and forth between positive and negative polarity. The electricity that comes from an American wall outlet is an example of AC. The current in North America is 120 VAC and changes direction 60 times per second. AC circuits can exhibit more interesting behaviors than DC circuits. For example, at low frequencies, a capacitor acts like an open circuit, so no current flows in the dielectric. However, when driven by an AC source, a capacitor will only accumulate a limited amount of charge before the potential difference changes polarity and the charge is returned to the source. The higher the frequency, the less charge will accumulate and the smaller the opposition to the current.

Both resistors and capacitors resist the flow of current when a voltage is applied. However, unlike in DC circuits, resistance may be frequency dependent. Frequencydependent resistance is known as *impedance*, a complex-valued quantity that can be broken into two parts: magnitude (the ratio of the voltage amplitude to the current amplitude) and phase (quantifies how much the current lags the voltage). Alternatively, we can break impedance down into its real and imaginary parts. Like in DC circuits, the real part of the impedance acts like resistance, resisting the flow of electric current. The imaginary part is called *reactance*, and it quantifies the opposition to a *change* in the current of a capacitive circuit element. Ideal capacitors are purely reactive, that is, they have zero resistance, and the impedance of a resistor is purely real, or resistive. Note this implies the current in a capacitor always lags the voltage by 90°. Impedance devices add like resistors in a DC circuit. For a set of components in series, the total impedance is the sum of the component impedances. To obtain the impedance of parallel circuit components, the inverse total impedance is given by the sum of the inverses of the component impedances.

Using different combinations of resistors and capacitors, RC circuits can be used to attenuate some frequencies, while allowing others to propagate through the circuit unaffected. For example, wiring a resistor in series with a load, and a capacitor in parallel with the same load, significantly attenuates high-frequency signals. Conversely, wiring a resistor in parallel with the load, and the capacitor in series, attenuates low-frequency signals. In Figure 2.4, at low frequencies, the reactance of the capacitor will be very large compared to the resistance of the resistor. This means that the voltage across the capacitor will be much larger than the voltage across the resistor. At high frequencies the 22 KYLE J. CURHAM and JOHN J. B. ALLEN

reverse is true: the voltage across the resistor is larger than across the capacitor. In other words, low frequencies pass to the output, and high frequencies are attenuated. This is known as a low-pass RC filter. Similarly, we can construct a high-pass filter by swapping the resistor and capacitor. The frequency cutoff for these *filters* is determined by the time-constant of the circuit, which is derived from the resistance and capacitance. The *cutoff frequency* for an RC circuit is:

$$f_c = \frac{1}{2\pi RC}$$

In the low-pass configuration, frequencies just above the cutoff are attenuated to half their original amplitude. Conversely, in the high-pass configuration, frequencies just below the cutoff are attenuated to half amplitude. The amount of attenuation increases as you move farther beyond the cutoff frequency. Figure 2.4 shows the amplitude roll-off as a function of frequency for a low-pass filter.