# **Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases**

# **NEUROANATOMY**

## third edition *through* Clinical Cases

### **HAL BLUMENFELD, M.D., Ph.D.**

Yale University School of Medicine

SINAUER ASSOCIATES

NEW YORK OXFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

#### *Note*

The author and the publisher have made every effort to provide clinical information in this book that is up-to-date and accurate at the time of publication. However, diagnostic and therapeutic methods evolve continuously based on new research and clinical experience. Because medical standards are constantly changing, and because of the possibility of human error, neither the author, nor the publisher, nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions, or for clinical results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are strongly encouraged to consult other sources to confirm all clinical information when caring for patients, particularly in regard to treatments and medications, doses, and contraindications, which are subject to frequent changes and improvements, or when using new or infrequently used drugs or other treatments.

#### *The Cover*

Human brain white matter tracts are revealed by MRI diffusion tractography. Fibers traveling in the anterior-posterior direction are shown in green, superior-inferior in blue, and medial-lateral in red. View is of the posterior left hemisphere seen from the left lateral surface. Modified with permission from Living Art Enterprises/Science Source.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

© 2022, 2010, 2002 Oxford University Press

Sinauer Associates is an imprint of Oxford University Press.

For titles covered by Section 112 of the US Higher Education Opportunity Act, please visit www.oup.com/us/he for the latest information about pricing and alternate formats.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization.

Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Address editorial correspondence to:

Sinauer Associates 23 Plumtree Road

Sunderland, MA 01375 USA

Address orders, sales, license, permissions, and translation inquiries to:

Oxford University Press USA

2001 Evans Road Cary, NC 27513 USA Orders: 1-800-445-9714

Notice of Trademarks

Throughout this book trademark names have been used, and in some instances, depicted. In lieu of appending the trademark symbol to each occurrence, the authors and publisher state that these trademarks are used in an editorial fashion, to the benefit of the trademark owners, and with no intent to infringe upon the trademarks.

ACCESSIBLE COLOR CONTENT Every opportunity has been taken to ensure that the content herein is fully accessible to those who have difficulty perceiving color. Exceptions are cases where the colors provided are expressly required because of the purpose of the illustration.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blumenfeld, Hal, author.

Title: Neuroanatomy through clinical cases / Hal Blumenfeld.

Description: Third edition. | New York, NY : Sinauer Associates/Oxford University

Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020004534 (print) | LCCN 2020004535 (ebook) | ISBN 9781605359625 (paperback) | ISBN 9781605359632 (ebook)

Subjects: MESH: Nervous System Diseases--diagnosis | Nervous System--anatomy & histology | Nervous System--pathology | Case Reports

Classification: LCC RC346 (print) | LCC RC346 (ebook) | NLM WL 141 | DDC 616.8--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004534

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004535

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

*To Michelle*

... ליבי כל כך

# *Brief Contents*

■ Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations 3 ■ Neuroanatomy Overview and Basic Definitions 13 ■ The Neurologic Exam as a Lesson in Neuroanatomy 49 ■ Introduction to Clinical Neuroradiology 85 ■ Brain and Environs: Cranium, Ventricles, and Meninges 125 ■ Corticospinal Tract and Other Motor Pathways 221 ■ Somatosensory Pathways 273 ■ Spinal Nerve Roots 317 ■ Major Plexuses and Peripheral Nerves 355 ■ Cerebral Hemispheres and Vascular Supply 389 ■ Visual System 459 ■ Brainstem I: Surface Anatomy and Cranial Nerves 495 ■ Brainstem II: Eye Movements and Pupillary Control 567 ■ Brainstem III: Internal Structures and Vascular Supply 615 ■ Cerebellum 699 ■ Basal Ganglia 741 ■ Pituitary and Hypothalamus 795 ■ Limbic System: Homeostasis, Olfaction, Memory, and Emotion 823 ■ Higher-Order Cerebral Function 887 Epilogue: A Simple Working Model of the Mind 987

# *Contents*

**PREFACE xvi HOW TO USE THIS BOOK xx**

## Chapter 1 *Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations 3*

| Introduction | 4 |

|--------------|---|

|--------------|---|

### **The General History and Physical Exam 4**

Chief Complaint (CC) 5 History of the Present Illness (HPI) 5 Past Medical History (PMH) 6

Review of Systems (ROS) 6 Family History (FHx) 6

Social and Environmental History (SocHx/EnvHx) 6

Medications and Allergies 6

Physical Exam 6 Laboratory Data 7 Assessment and Plan 7

**Neurologic Differential Diagnosis 7**

**Relationship between the General Physical Exam and the Neurologic Exam 8**

**Conclusions 10 References 10**

## Chapter 2 *Neuroanatomy Overview and Basic Definitions 13*

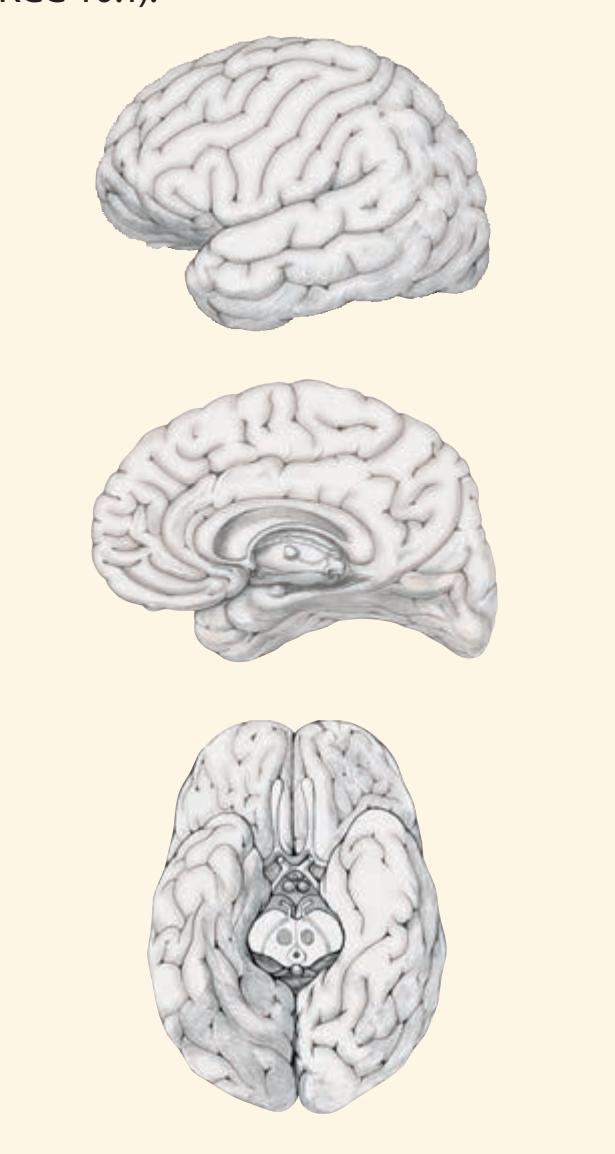

### **Basic Macroscopic Organization of the Nervous System 14**

Main Parts of the Nervous System 14 Orientation and Planes of Section 16

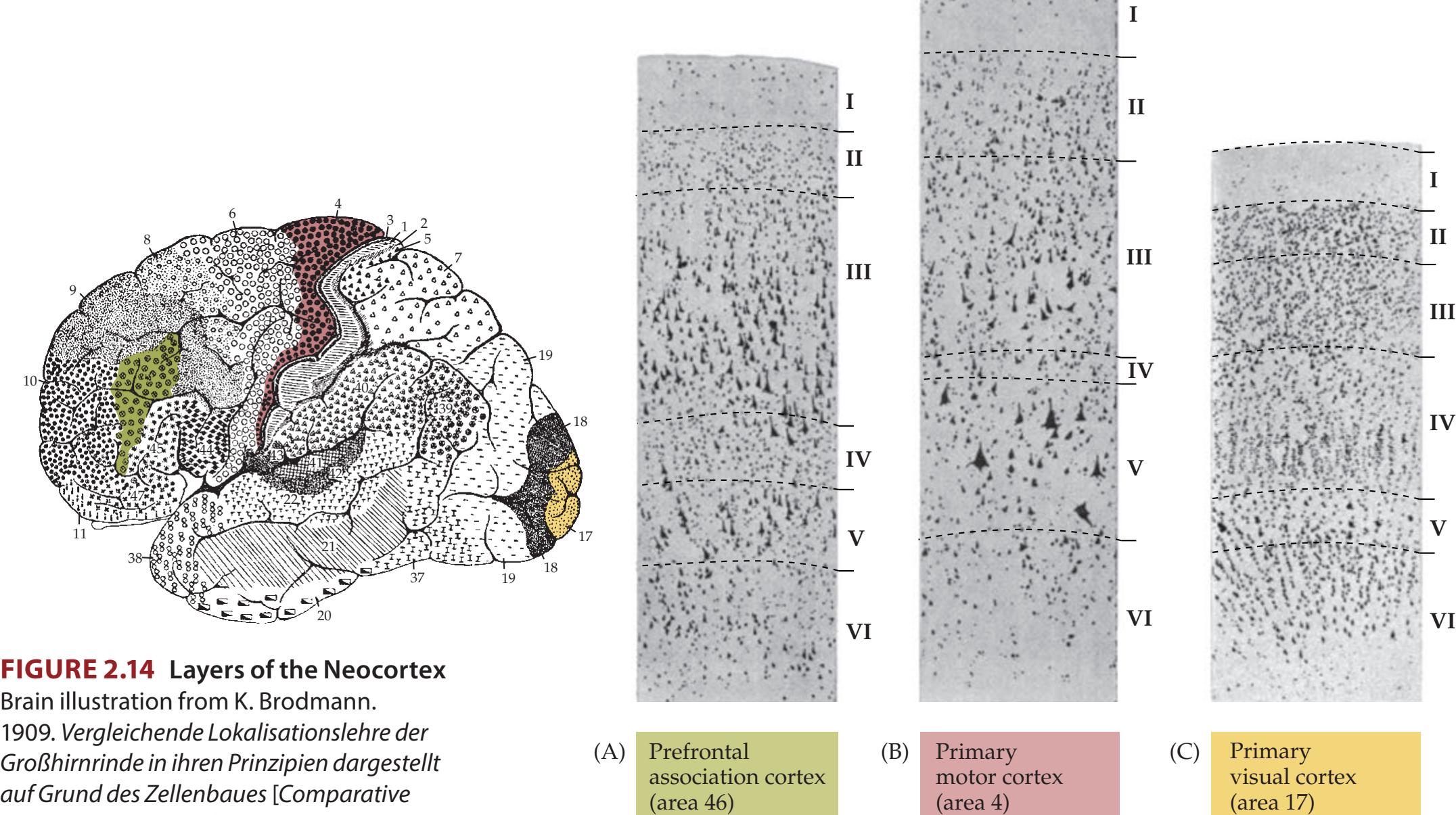

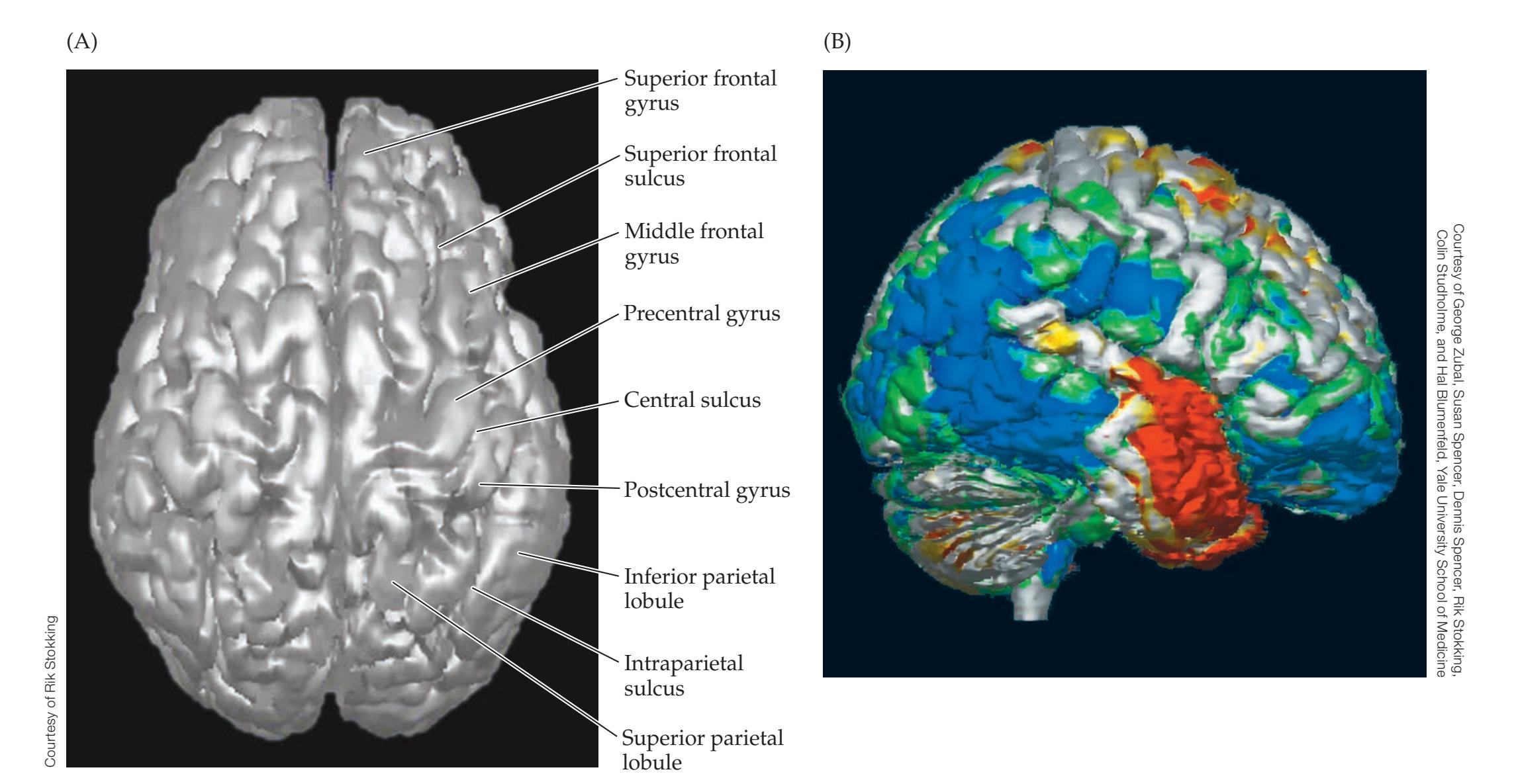

the Cerebral Cortex 29

**Basic Cellular and Neurochemical Organization of the Nervous System 17**

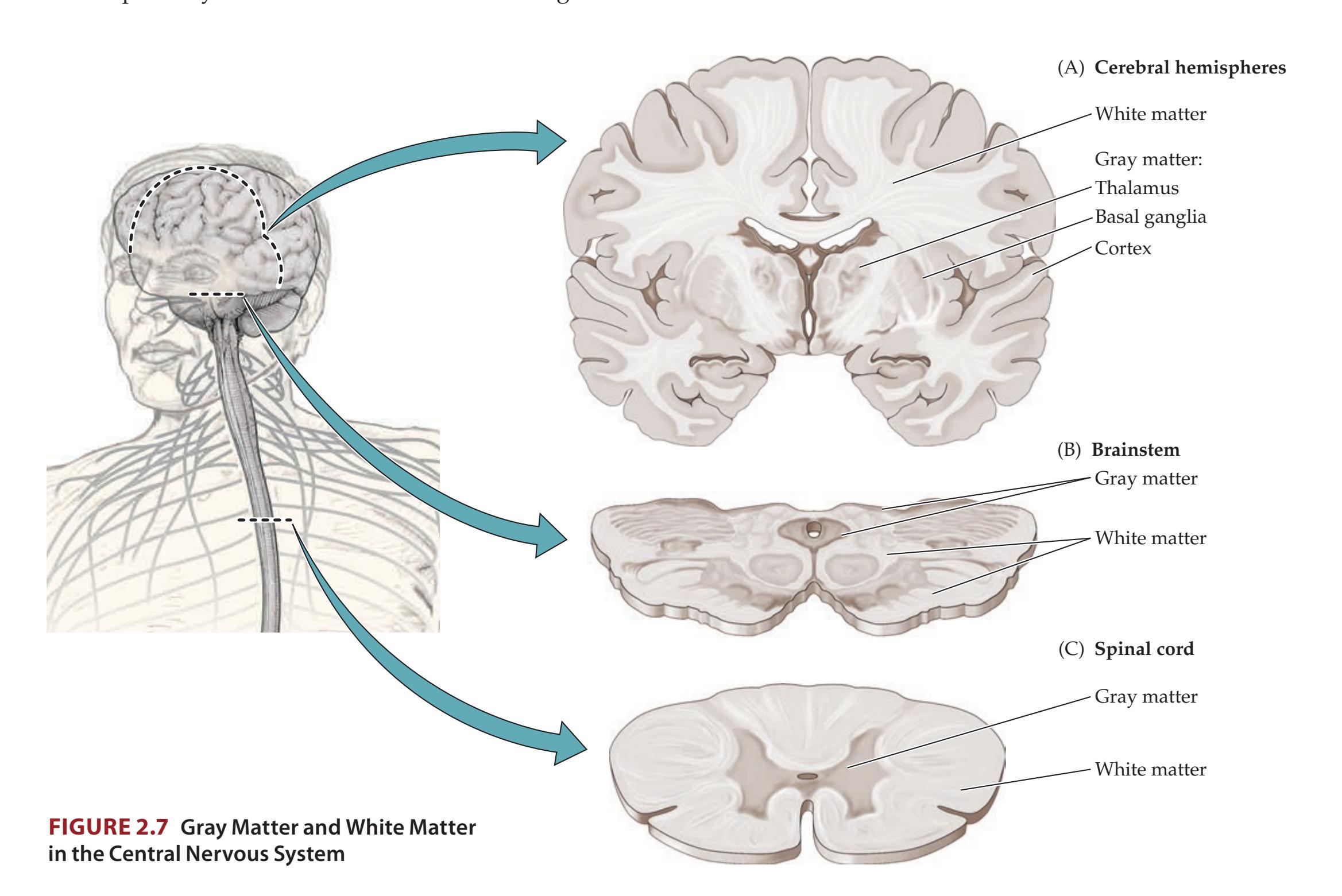

**CNS Gray Matter and White Matter; PNS Ganglia and Nerves 21**

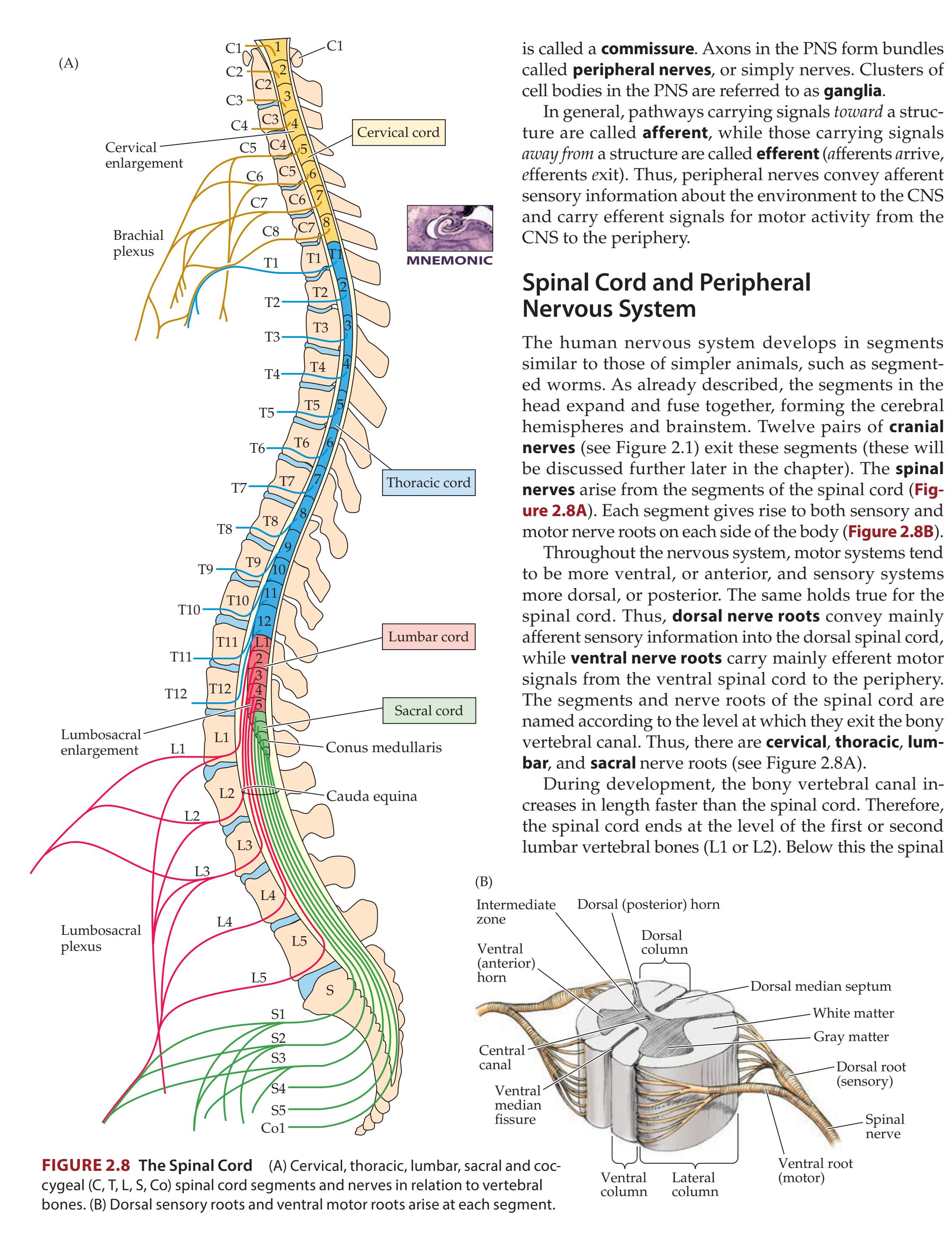

**Spinal Cord and Peripheral Nervous System 22**

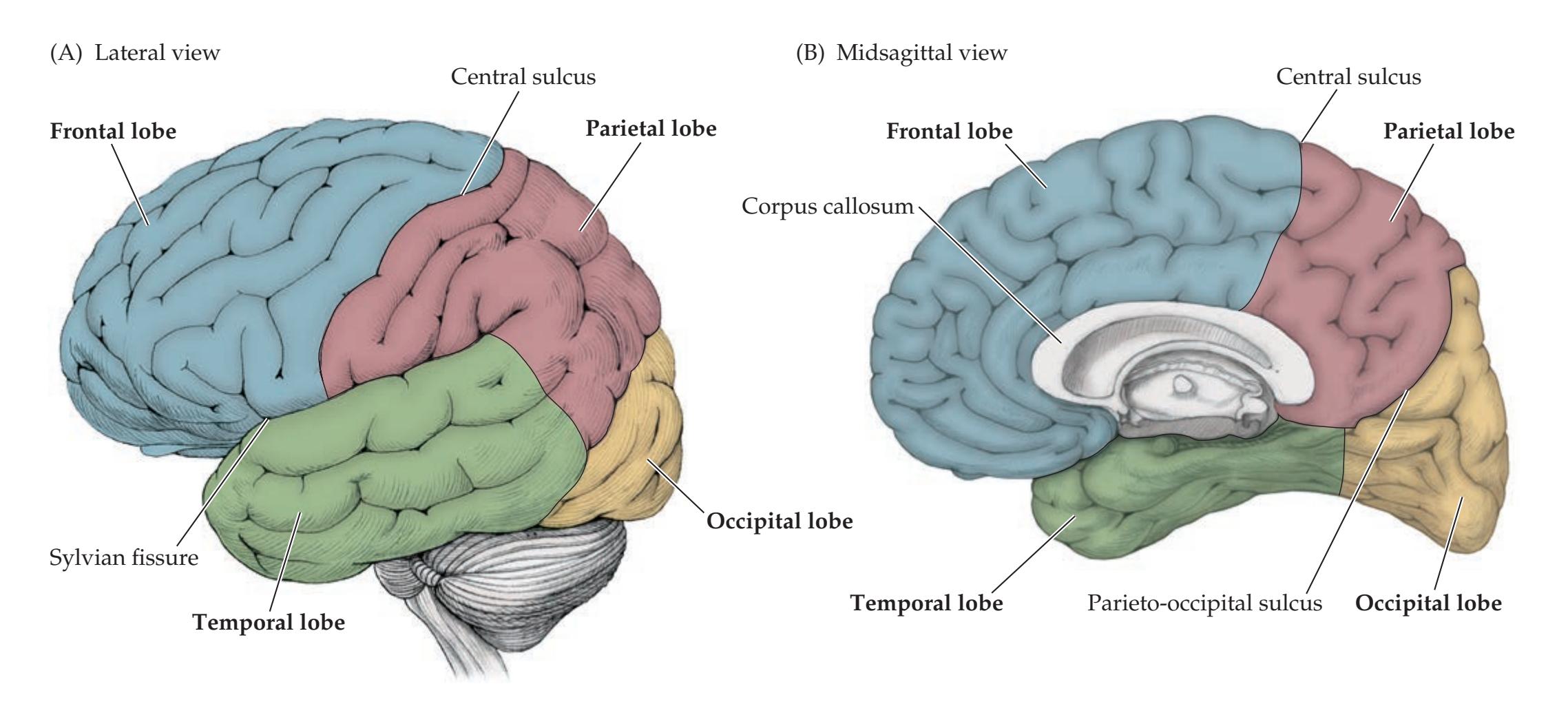

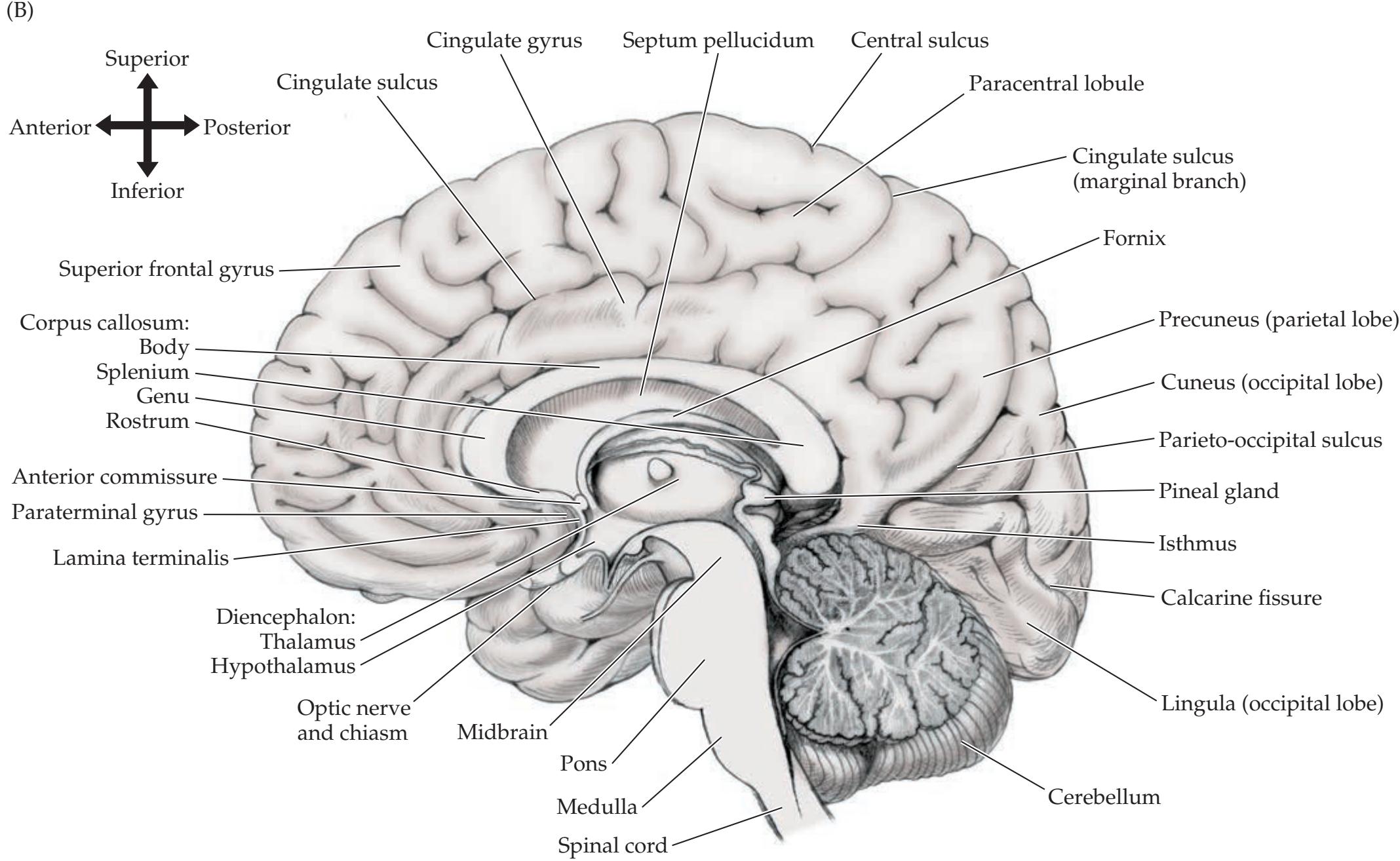

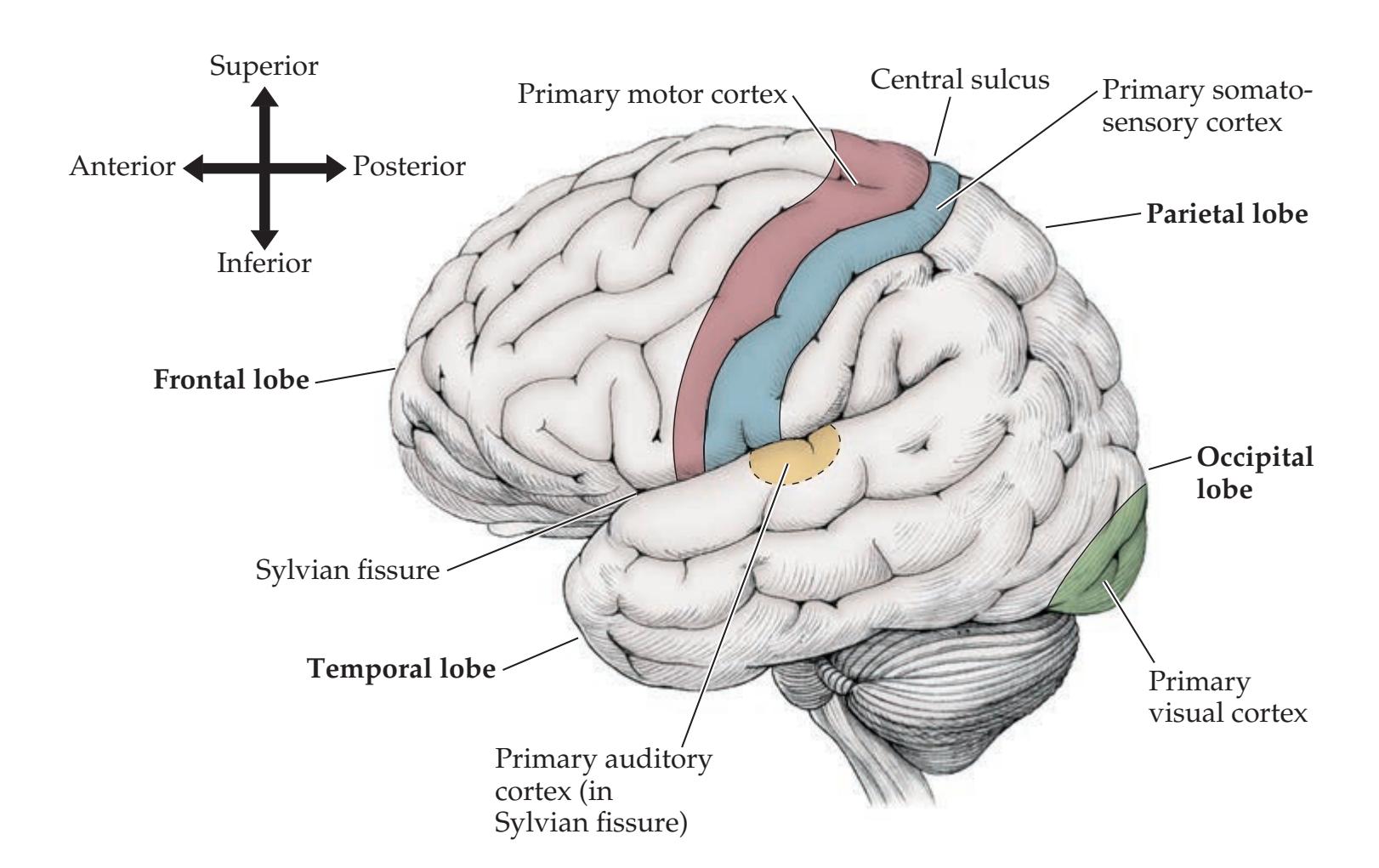

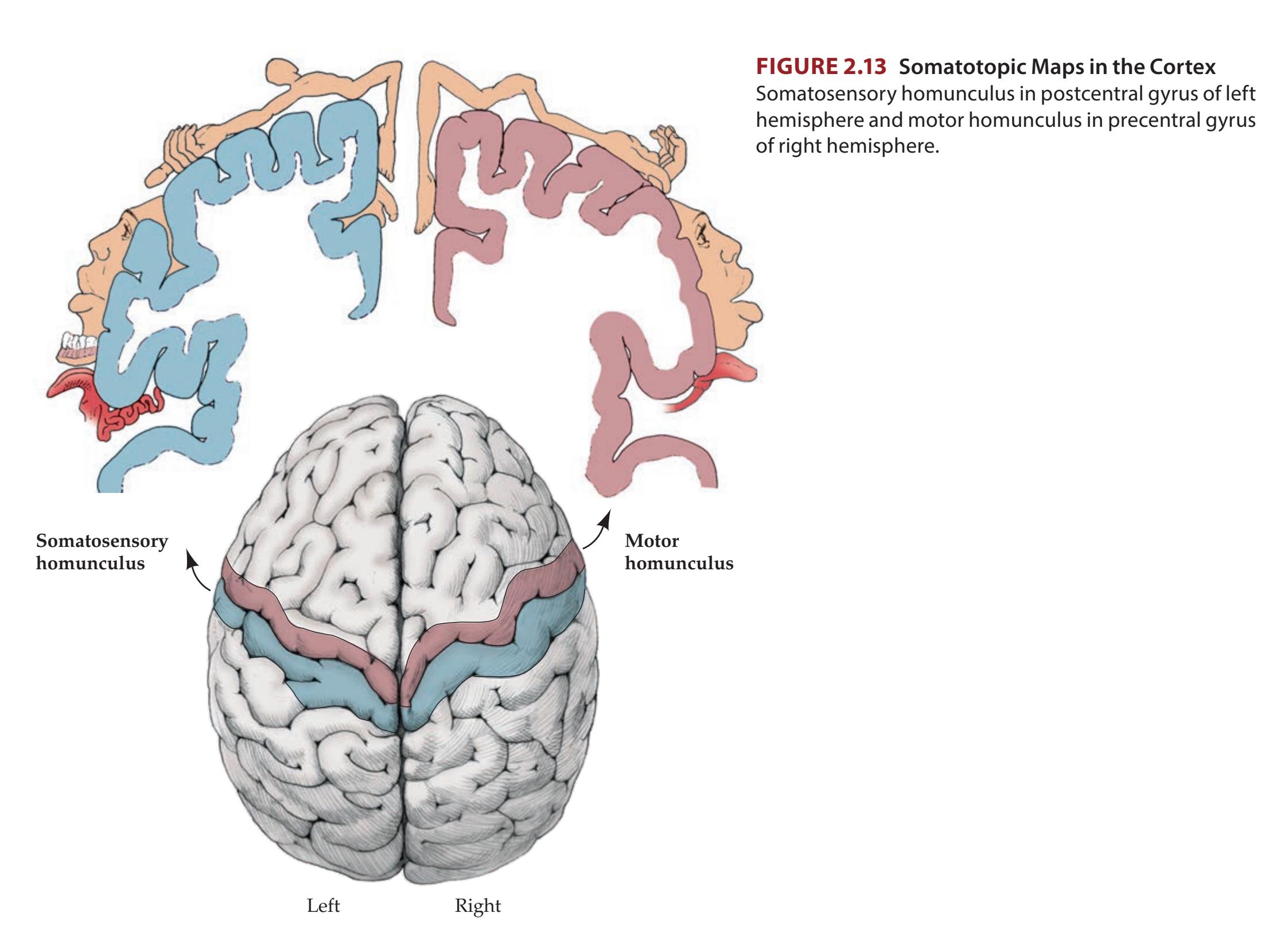

**Cerebral Cortex: Basic Organization and Primary Sensory and Motor Areas 24**

Lobes of the Cerebral Hemispheres 24 Surface Anatomy of the Cerebral Hemispheres in Detail 25 Primary Sensory and Motor Areas 28 Cell Layers and Regional Classification of

**Motor Systems 32**

Main Motor Pathways 32

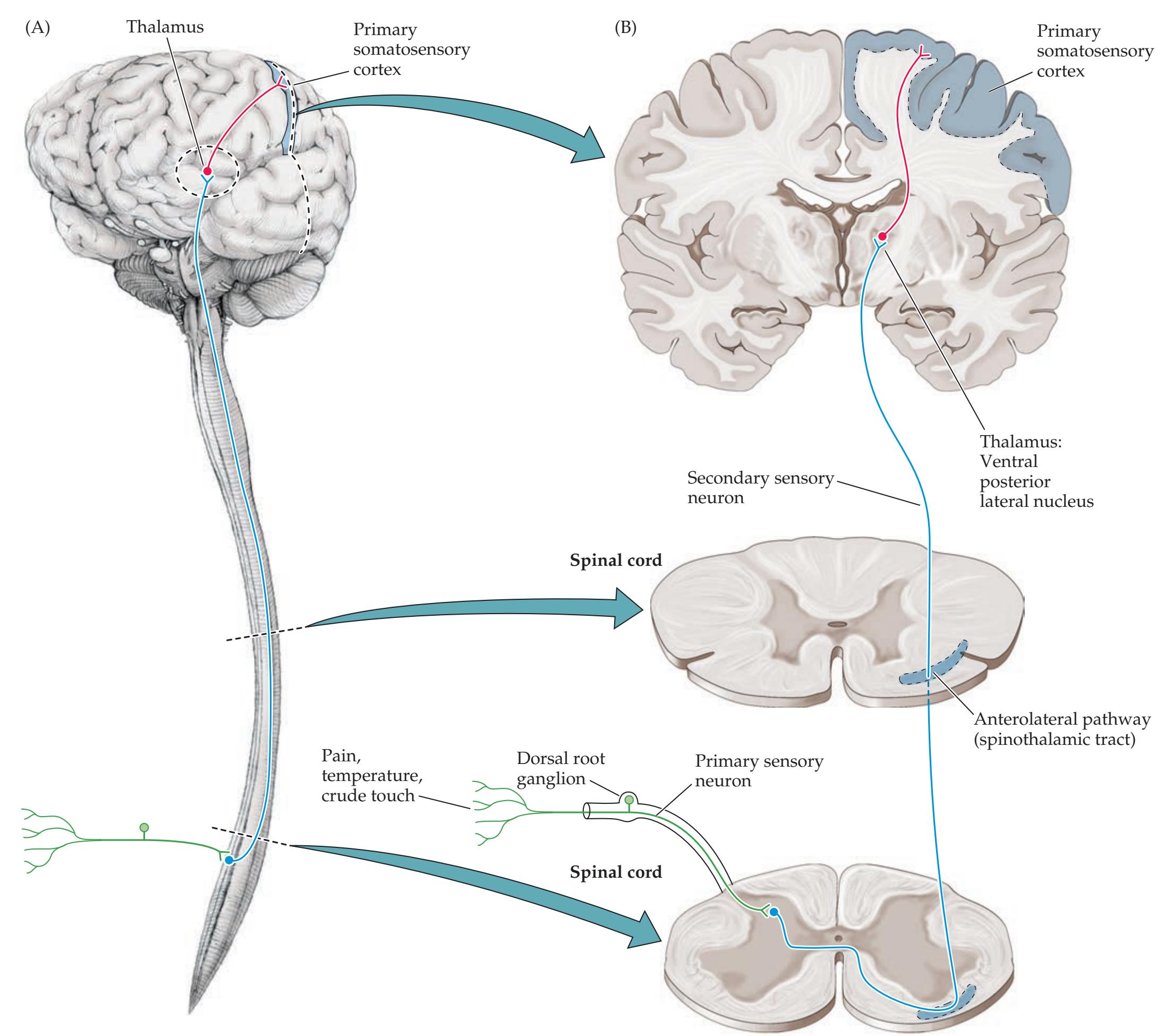

Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia 34 **Somatosensory Systems 34**

Main Somatosensory Pathways 34

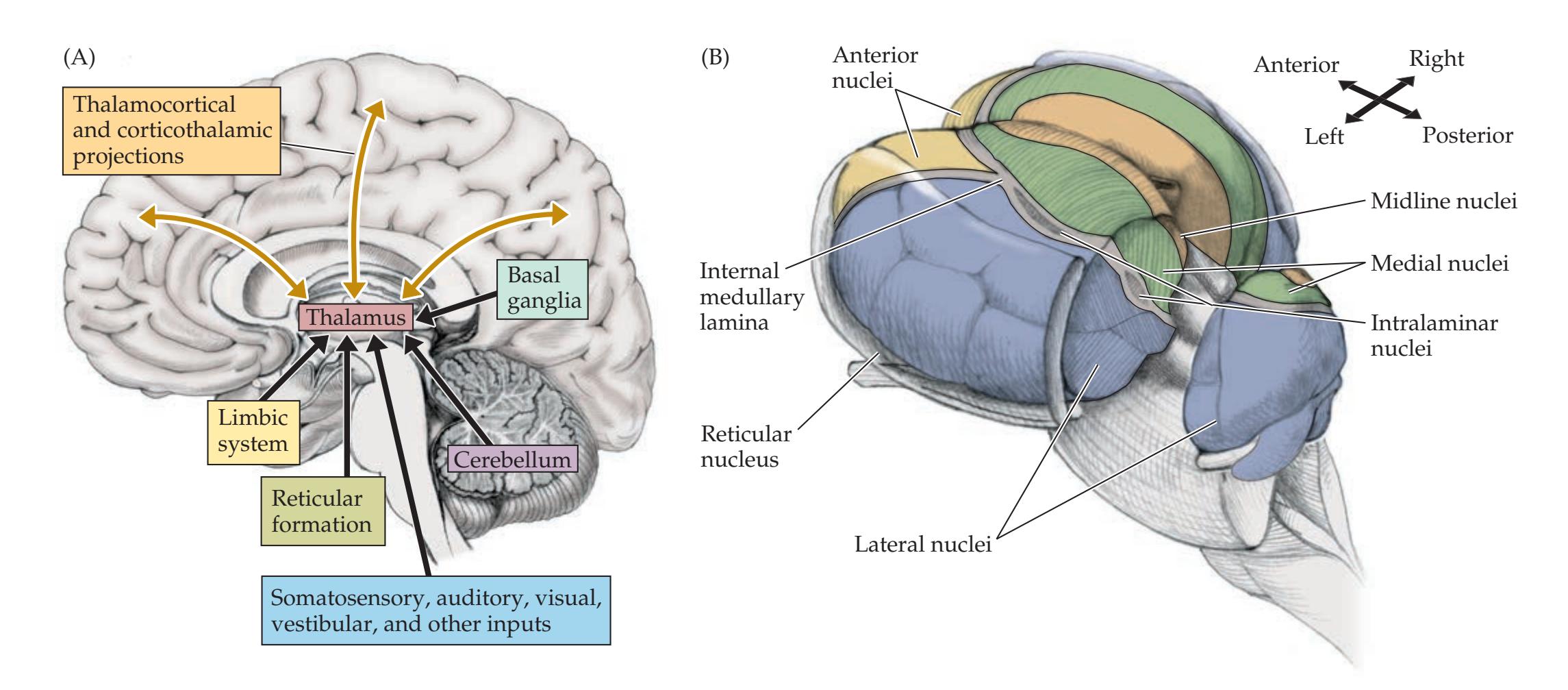

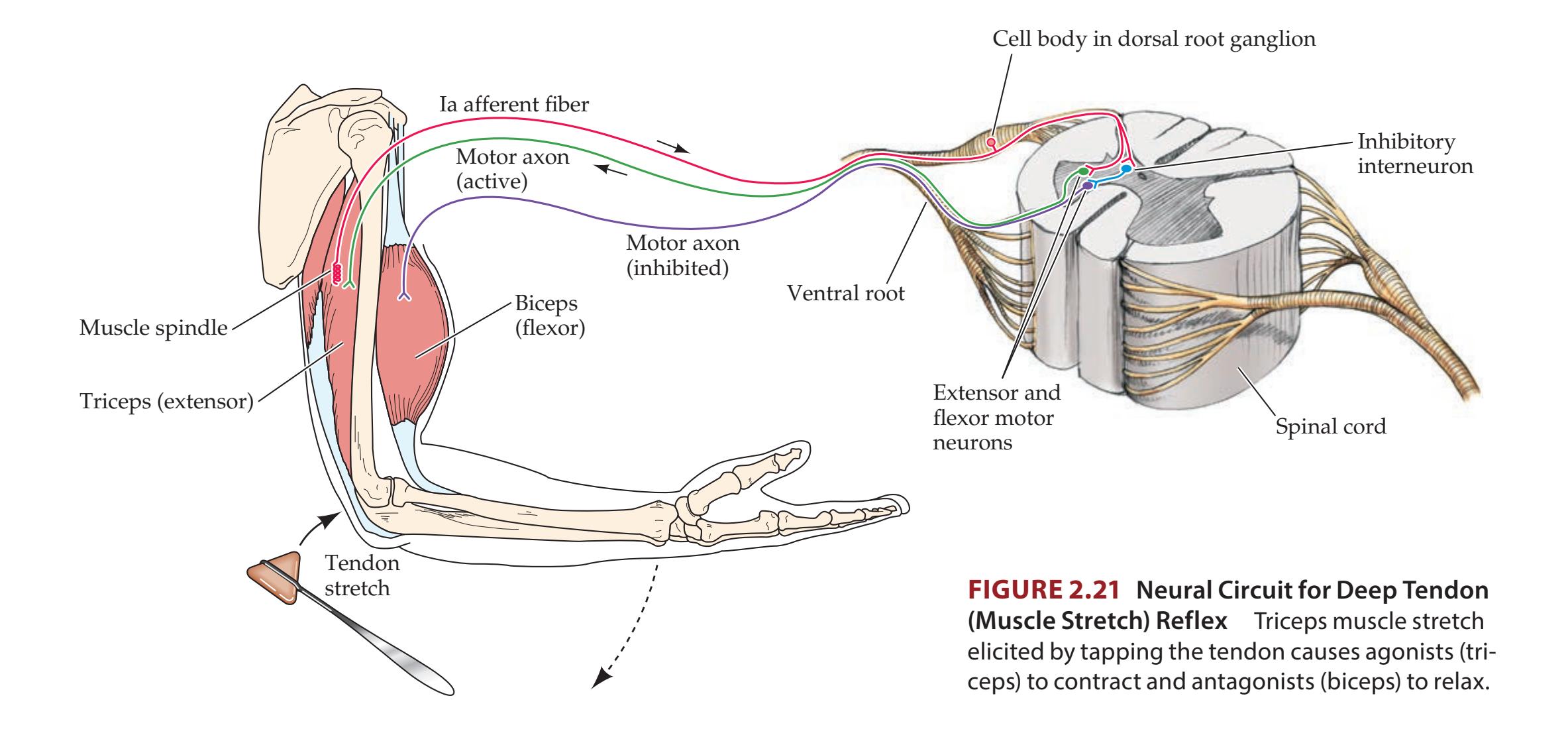

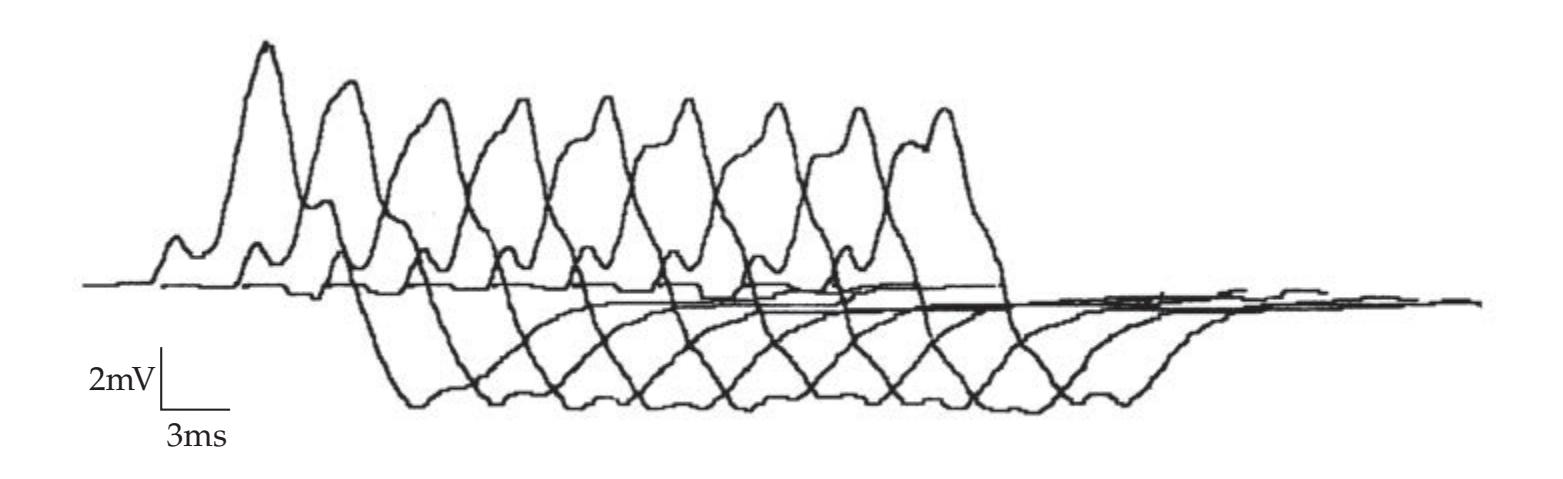

Thalamus 35 **Stretch Reflex 37**

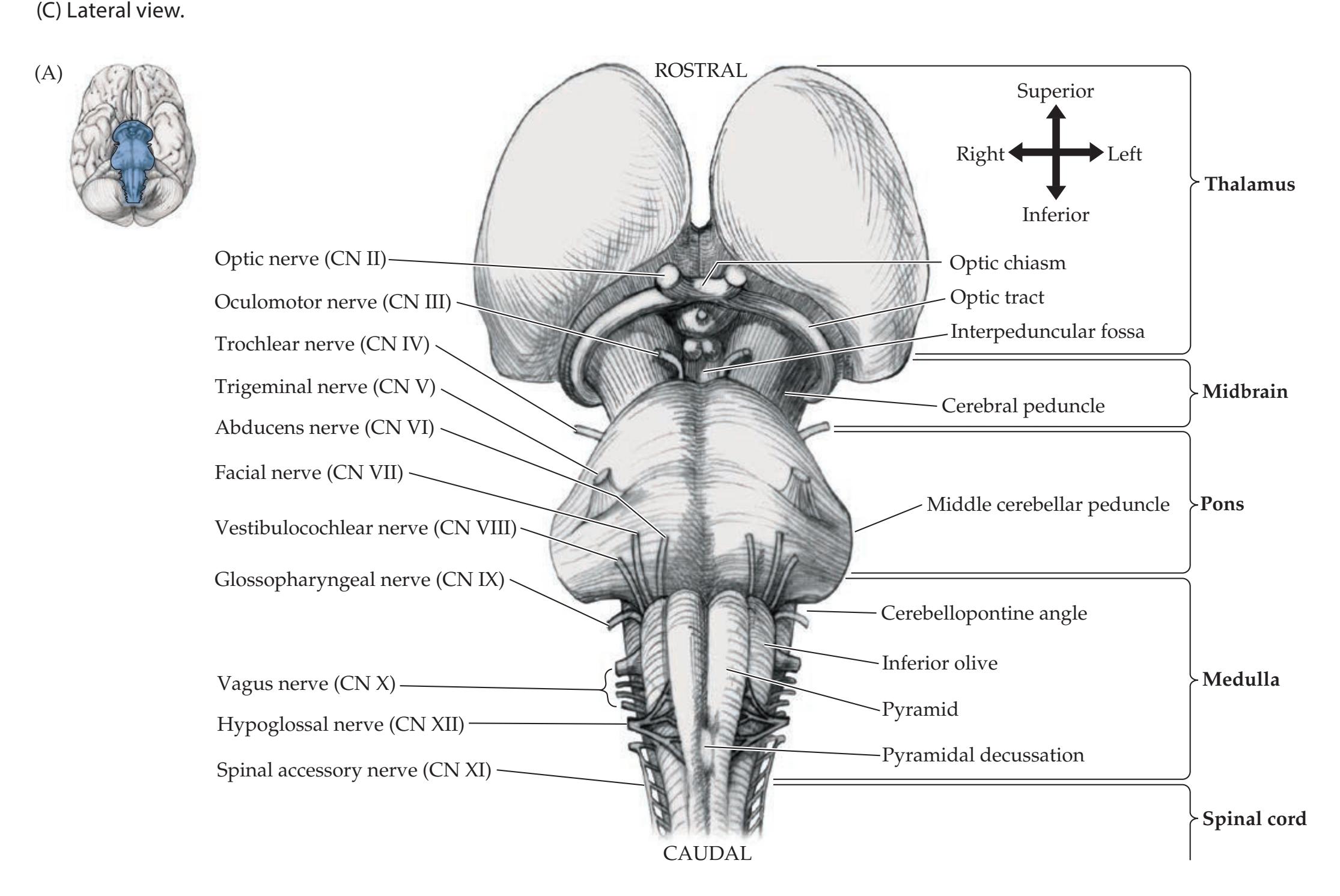

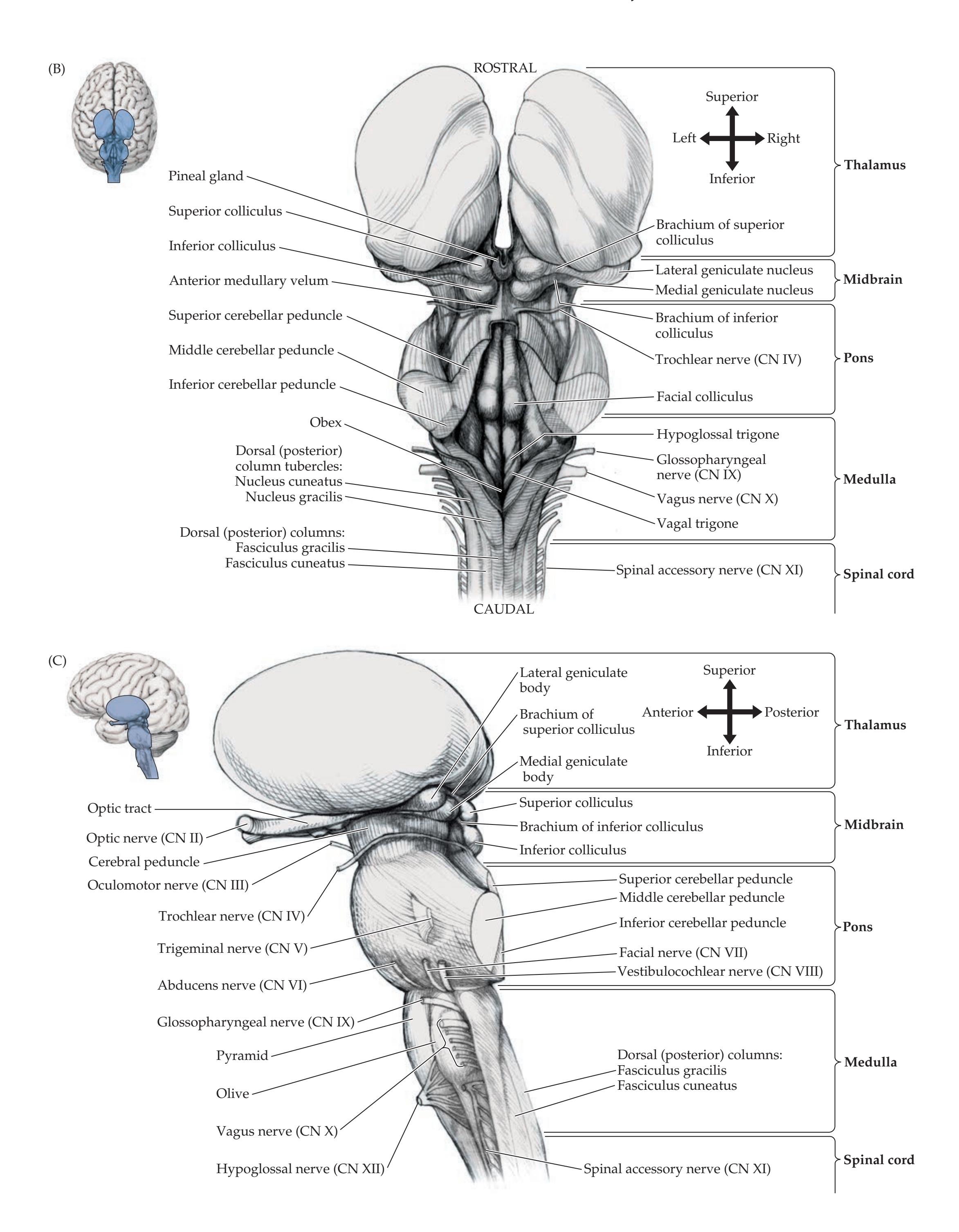

**Brainstem and Cranial Nerves 38**

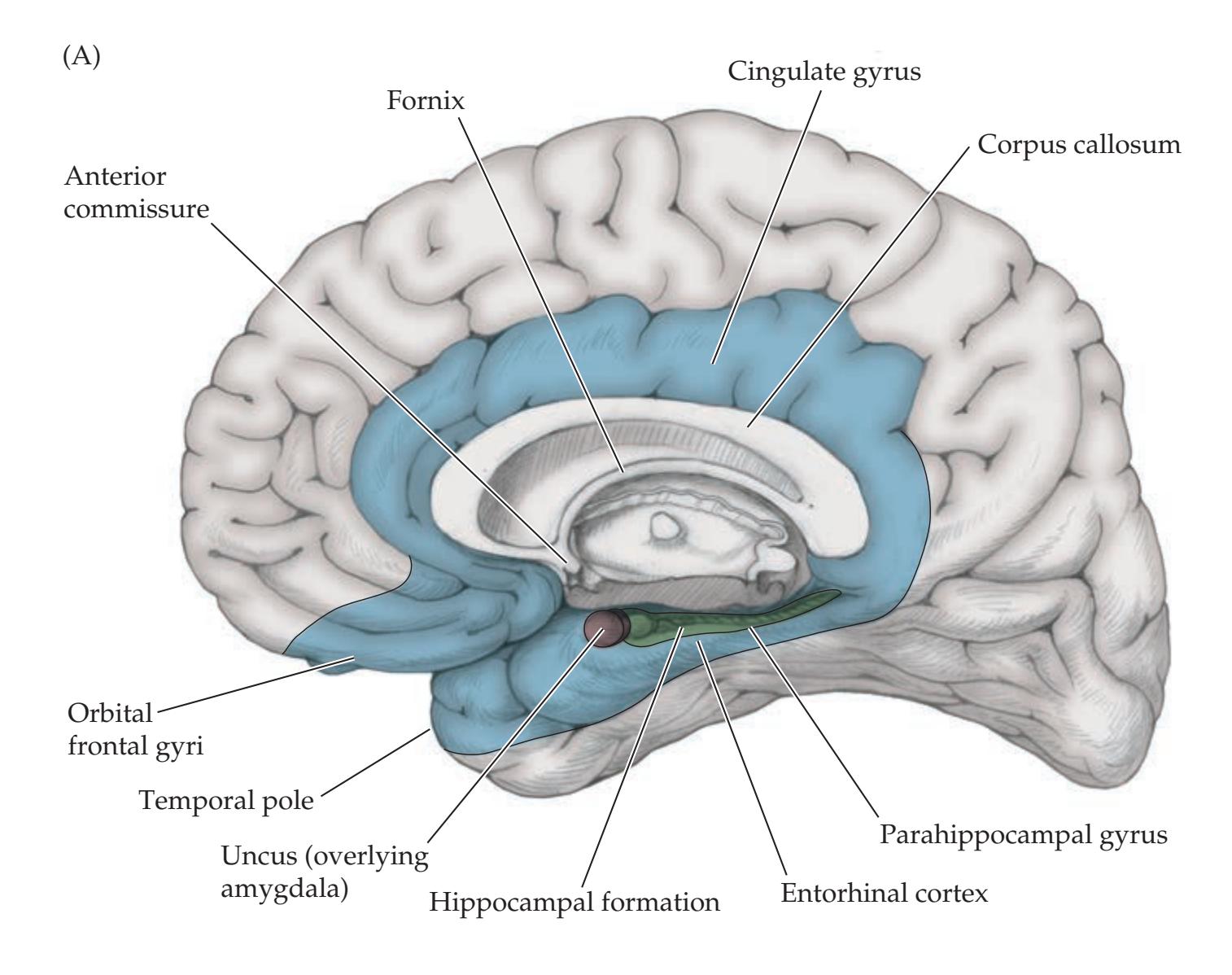

**Limbic System 41 Association Cortex 41**

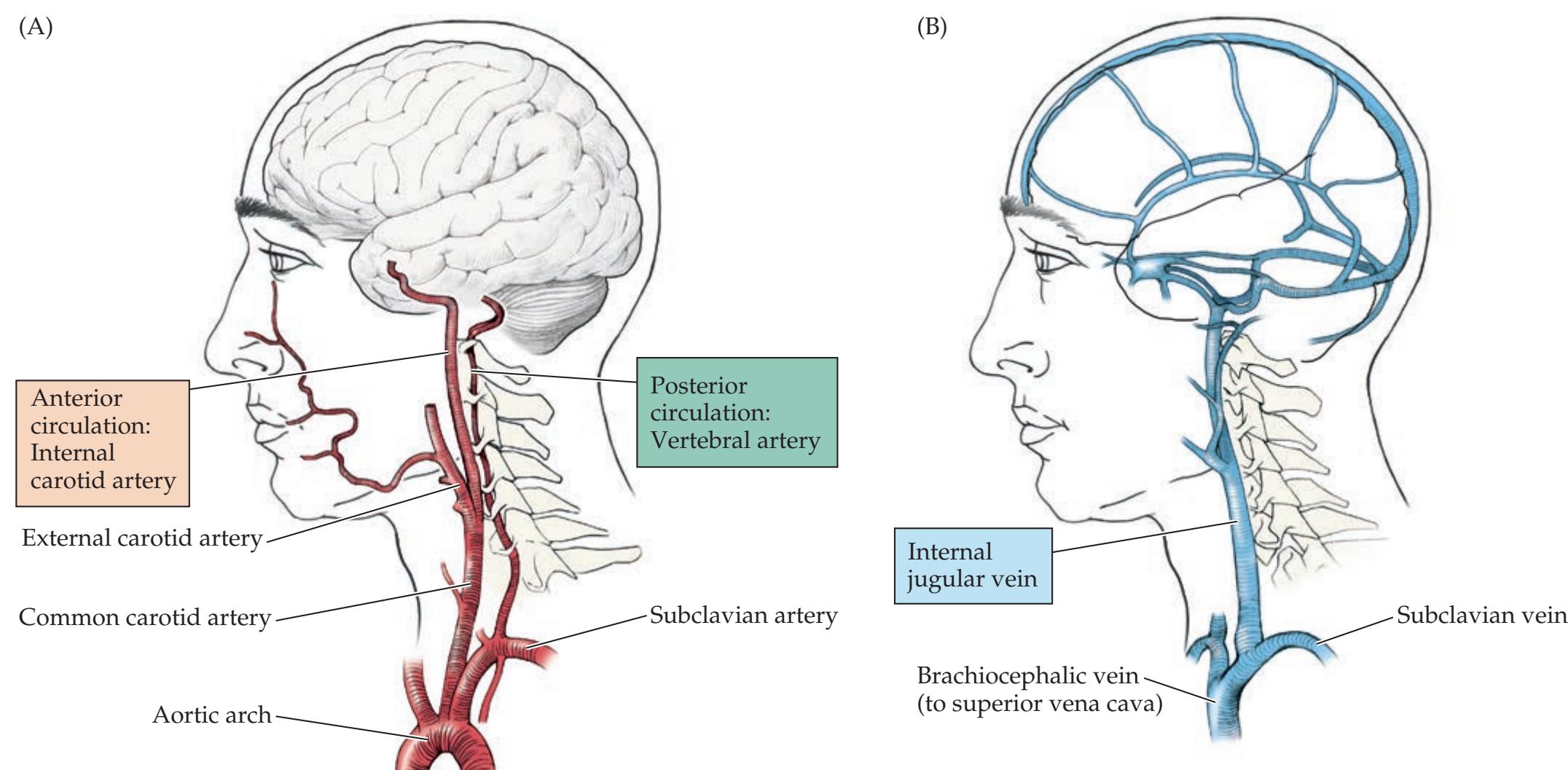

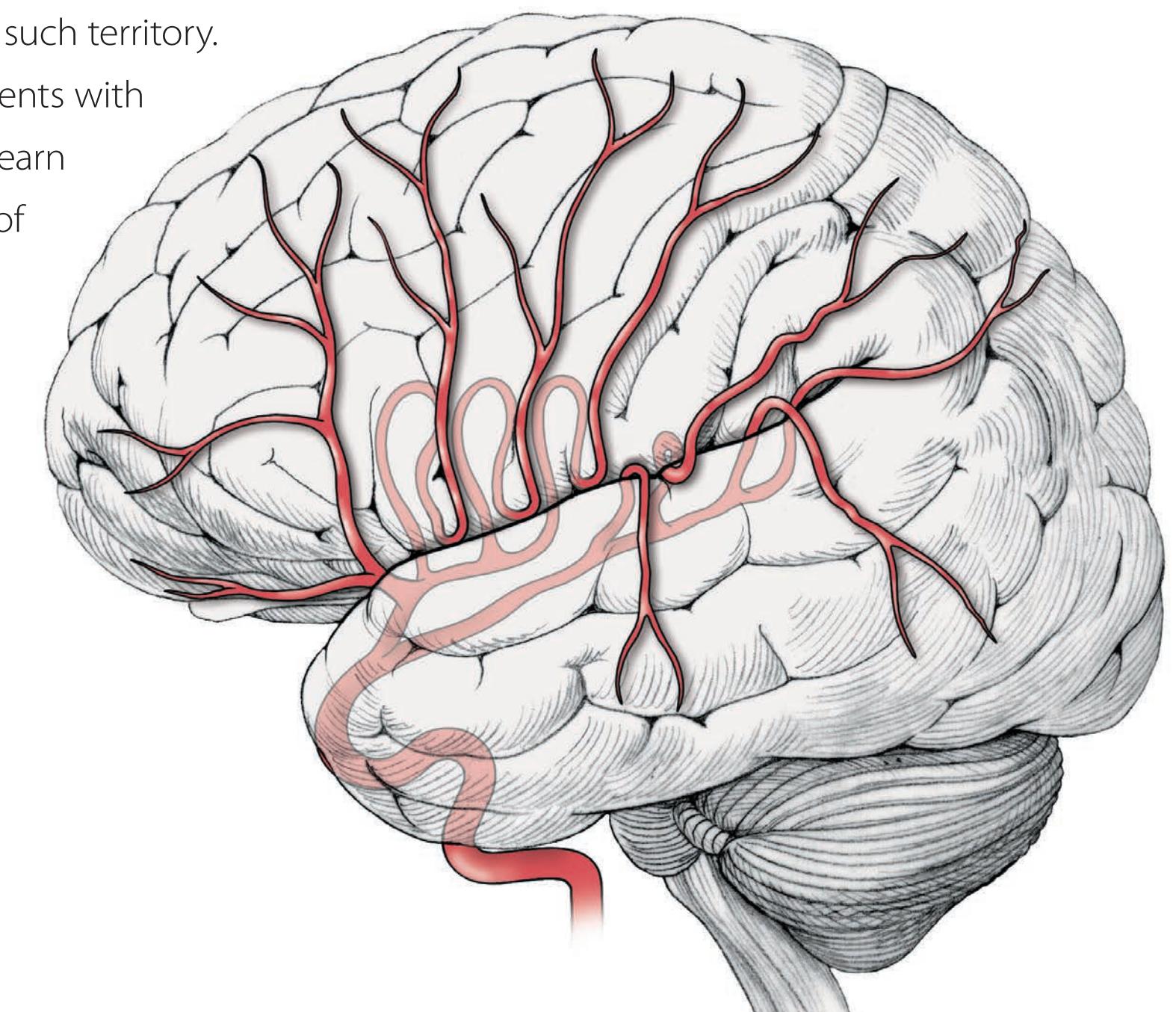

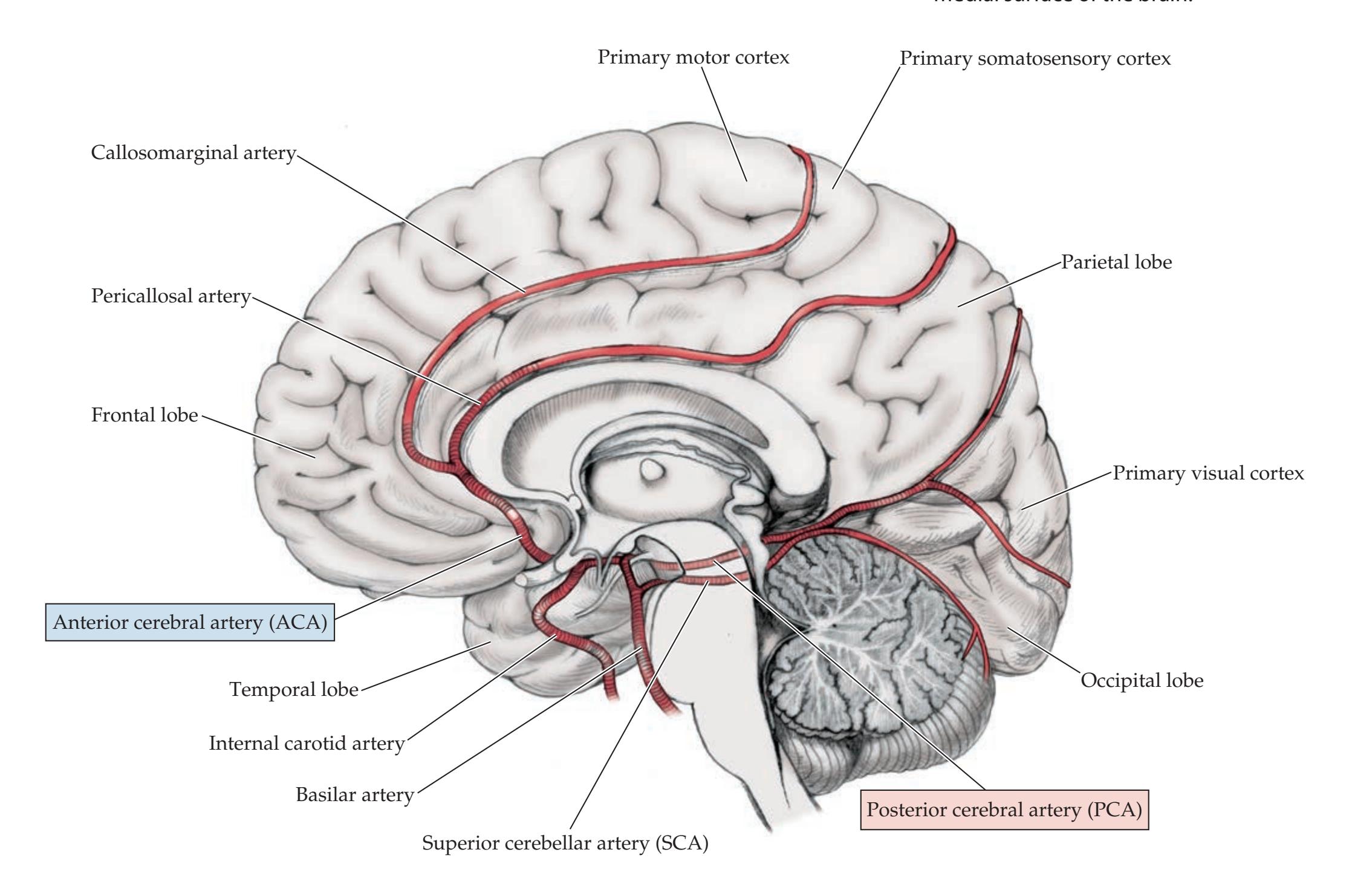

**Blood Supply to the Brain and Spinal Cord 44**

**Conclusions 46 References 46**

**viii** Contents

## Chapter 3 *The Neurologic Exam as a Lesson in Neuroanatomy 49*

**Overview of the Neurologic Exam 50**

**neuroexam.com 52**

**The Neurologic Exam: Examination Technique and What Is Being Tested 52**

- 1. Mental Status 52

- 2. Cranial Nerves 58

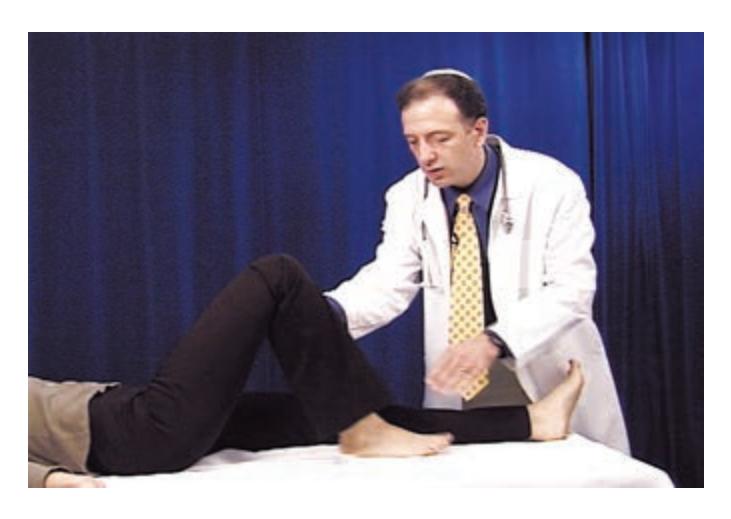

- 3. Motor Exam 63

- 4. Reflexes 66

- 5. Coordination and Gait 68

- 6. Sensory Exam 71

**The Neurologic Exam as a Flexible Tool 72**

Exam Limitations and Strategies 73

**Coma Exam 73**

General Physical Exam 74

- 1. Mental Status 75

- 2. Cranial Nerves 76

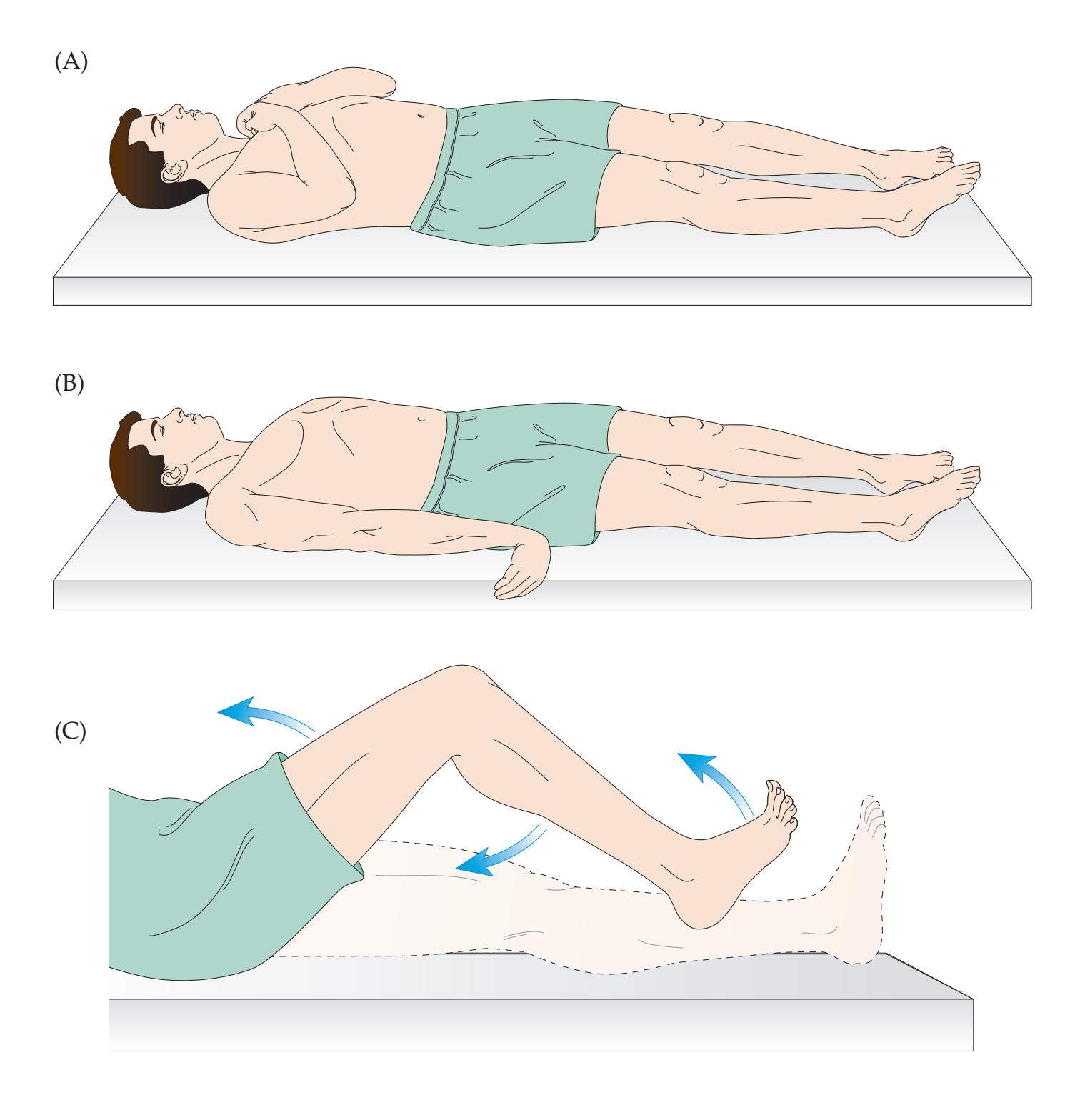

- 3. Sensory Exam and 4. Motor Exam 77

- 5. Reflexes 77

- 6. Coordination and Gait 79

**Brain Death 79**

**Conversion Disorder, Malingering, and**

**Related Disorders 79**

**The Screening Neurologic Exam 81**

**Conclusions 81 References 46**

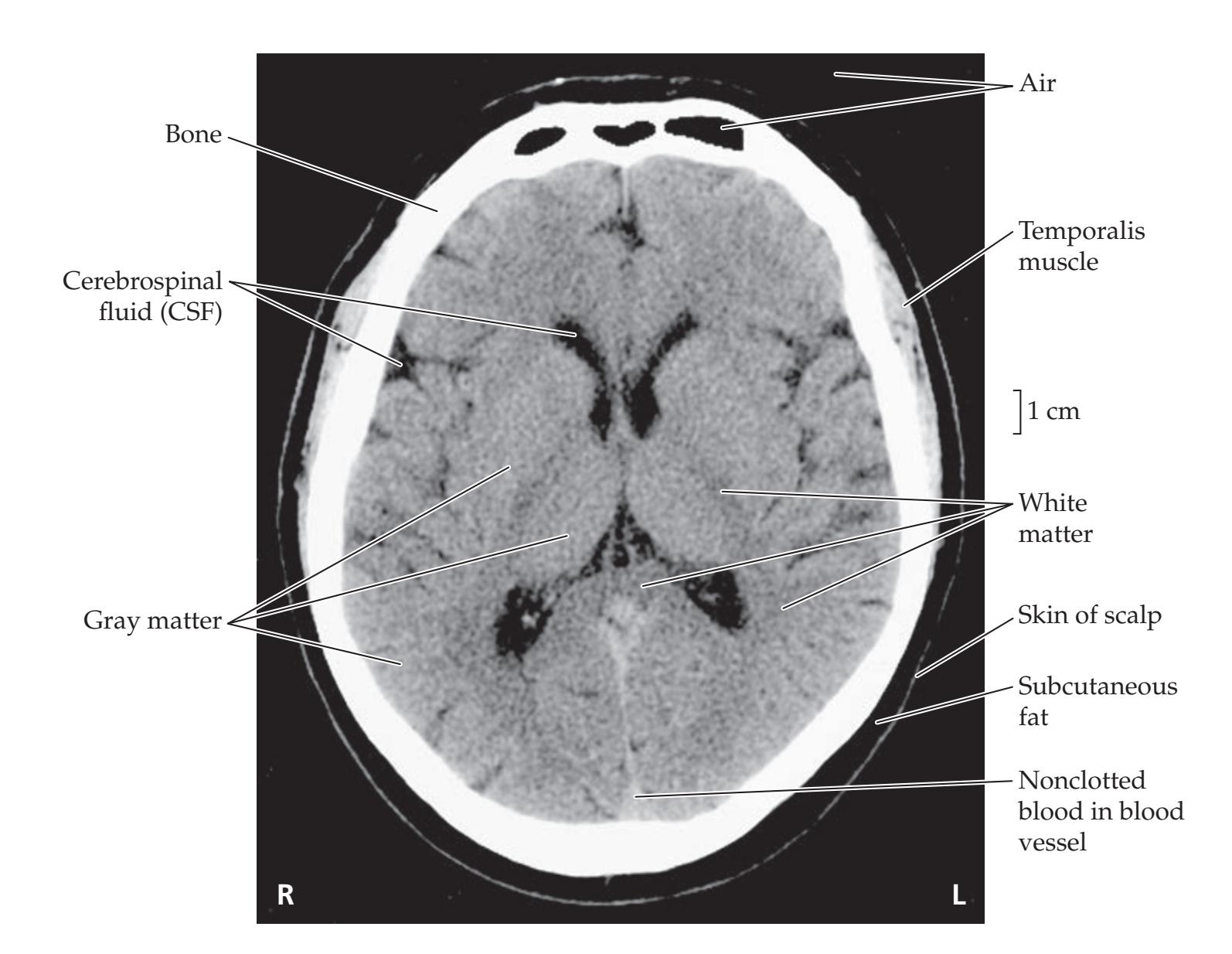

## Chapter 4 *Introduction to Clinical Neuroradiology 85*

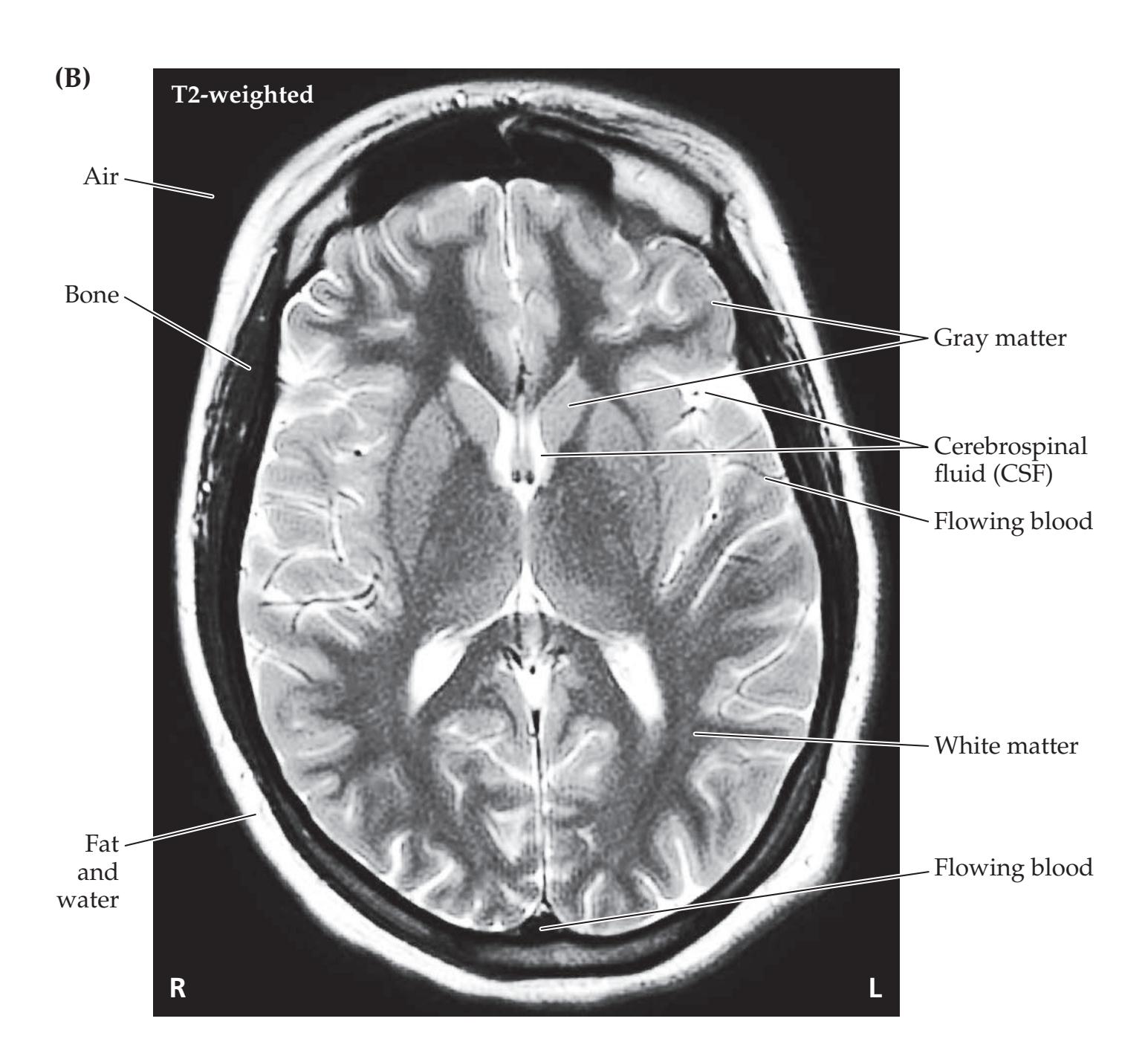

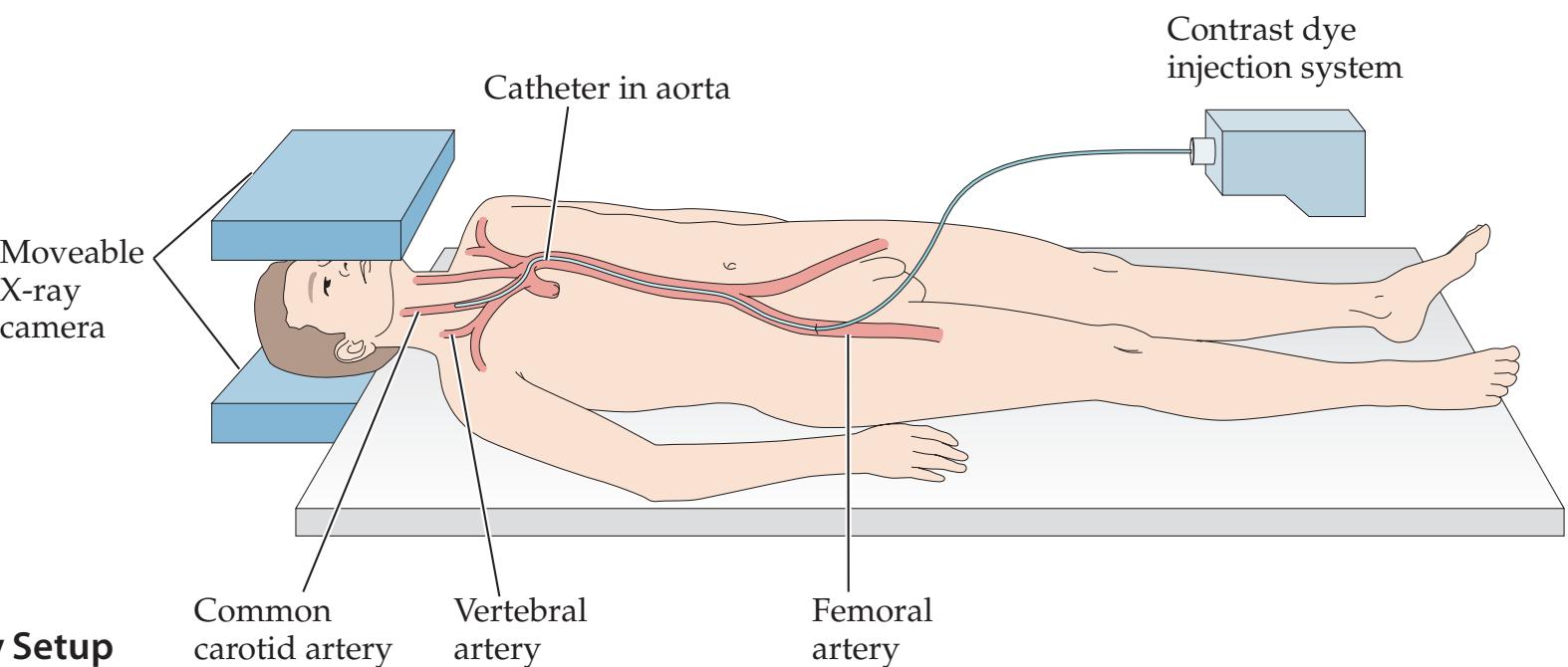

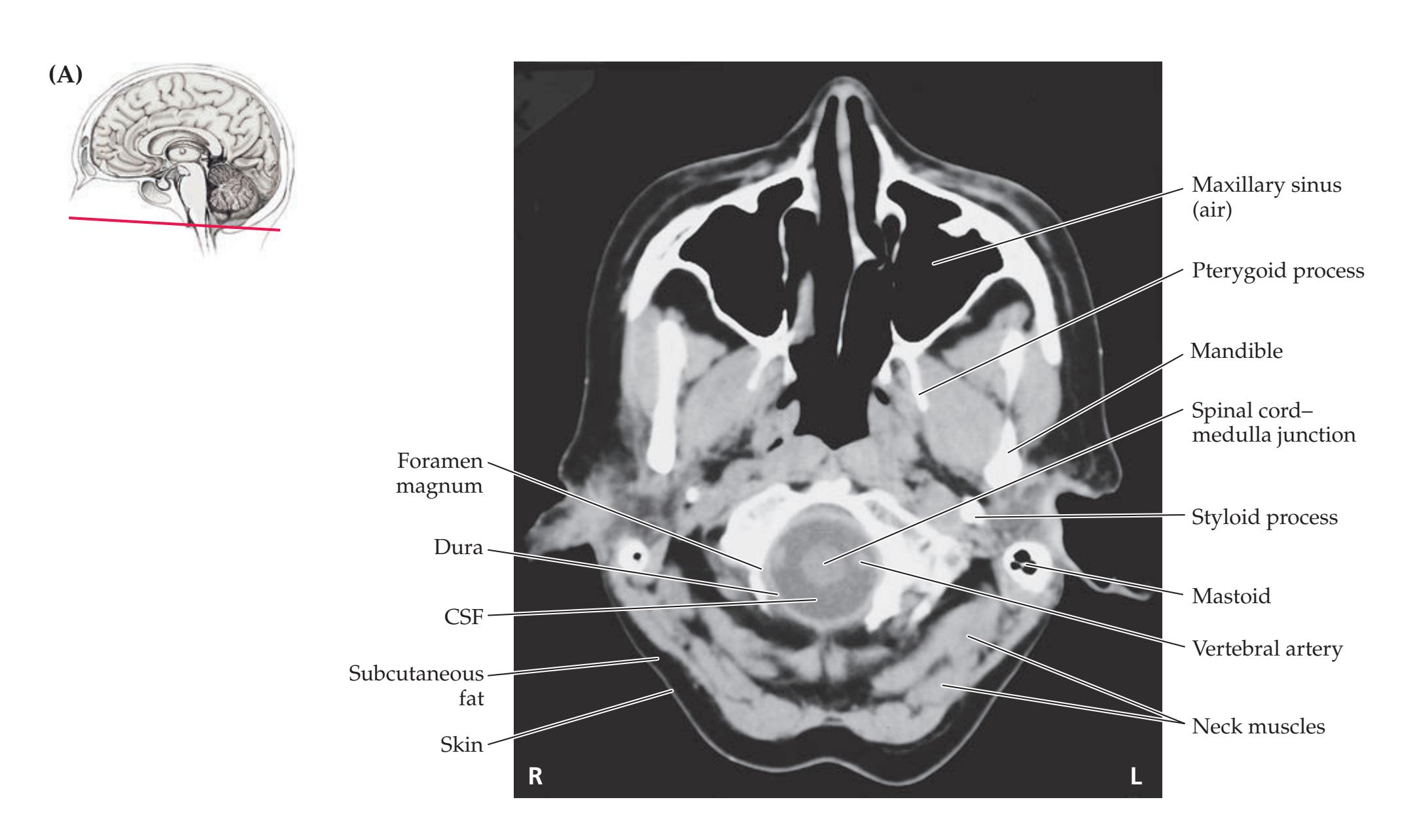

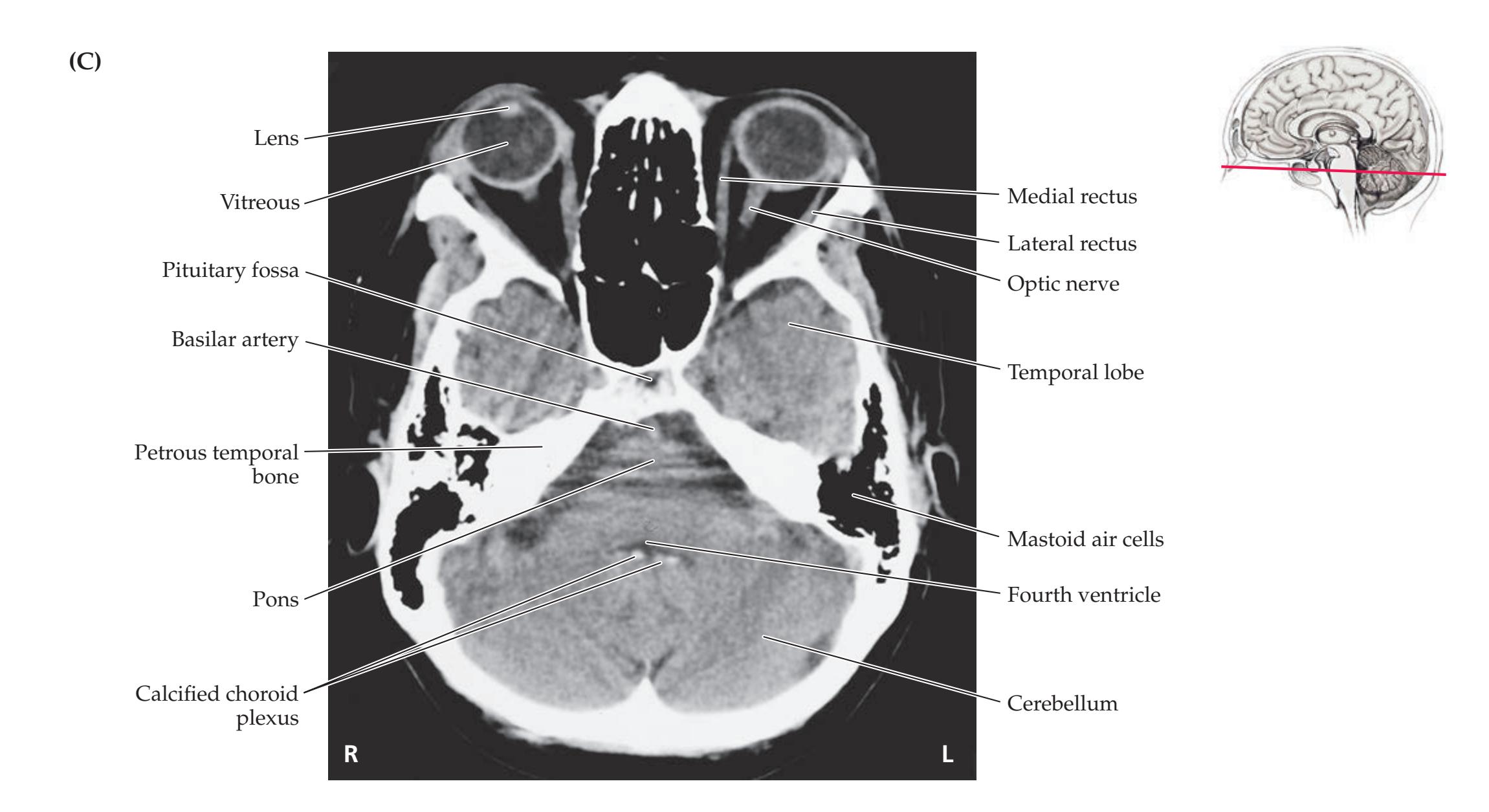

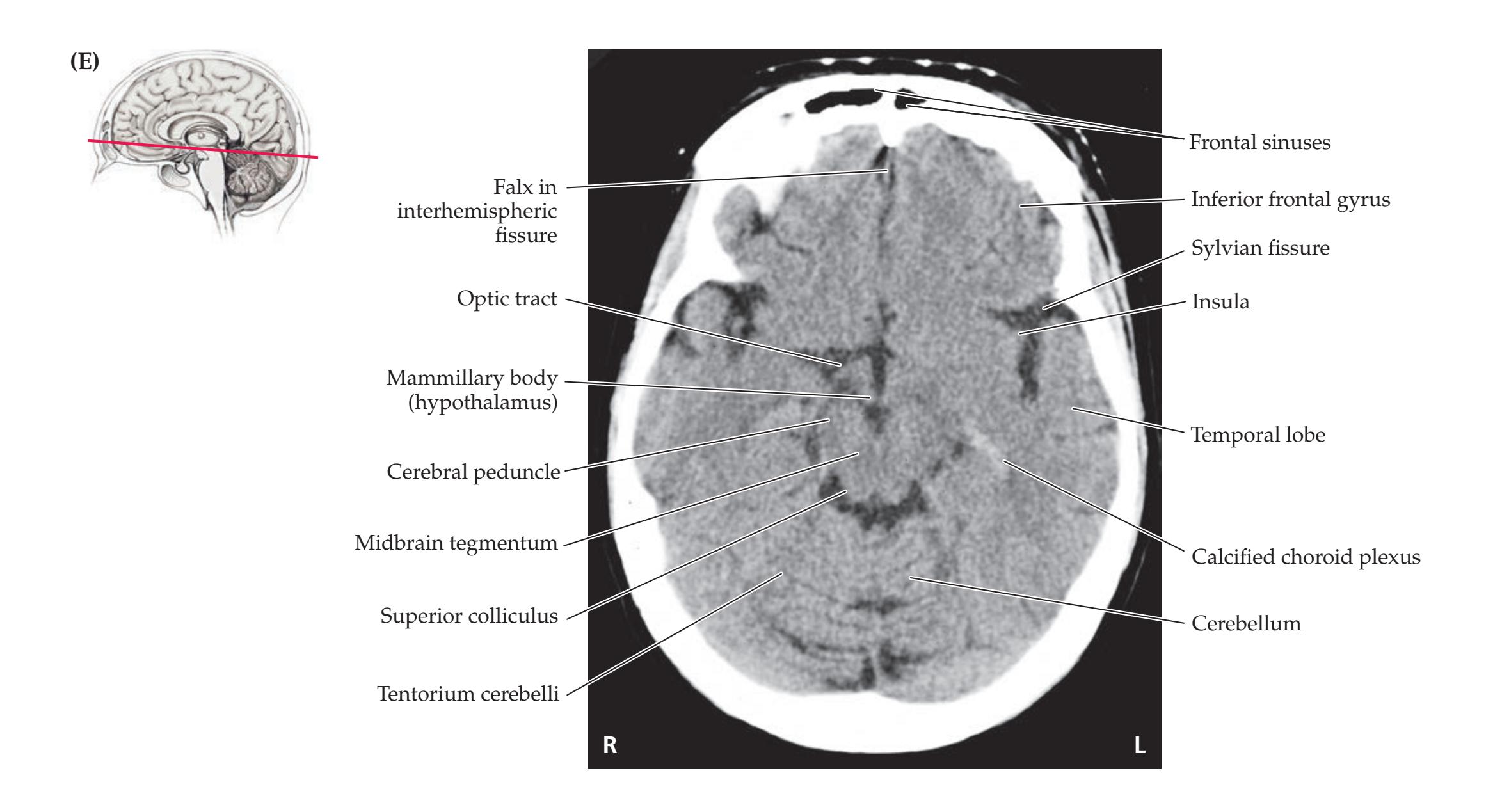

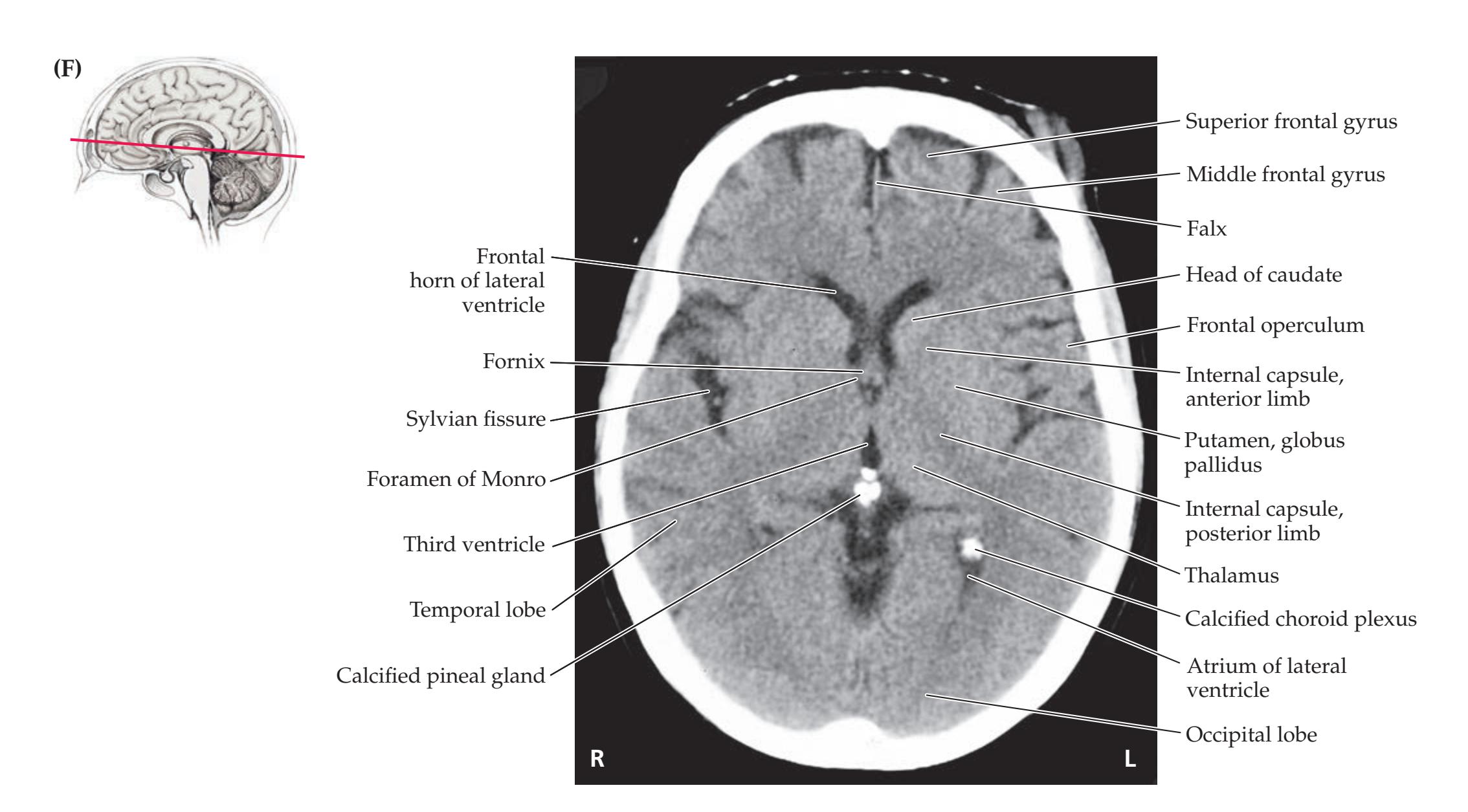

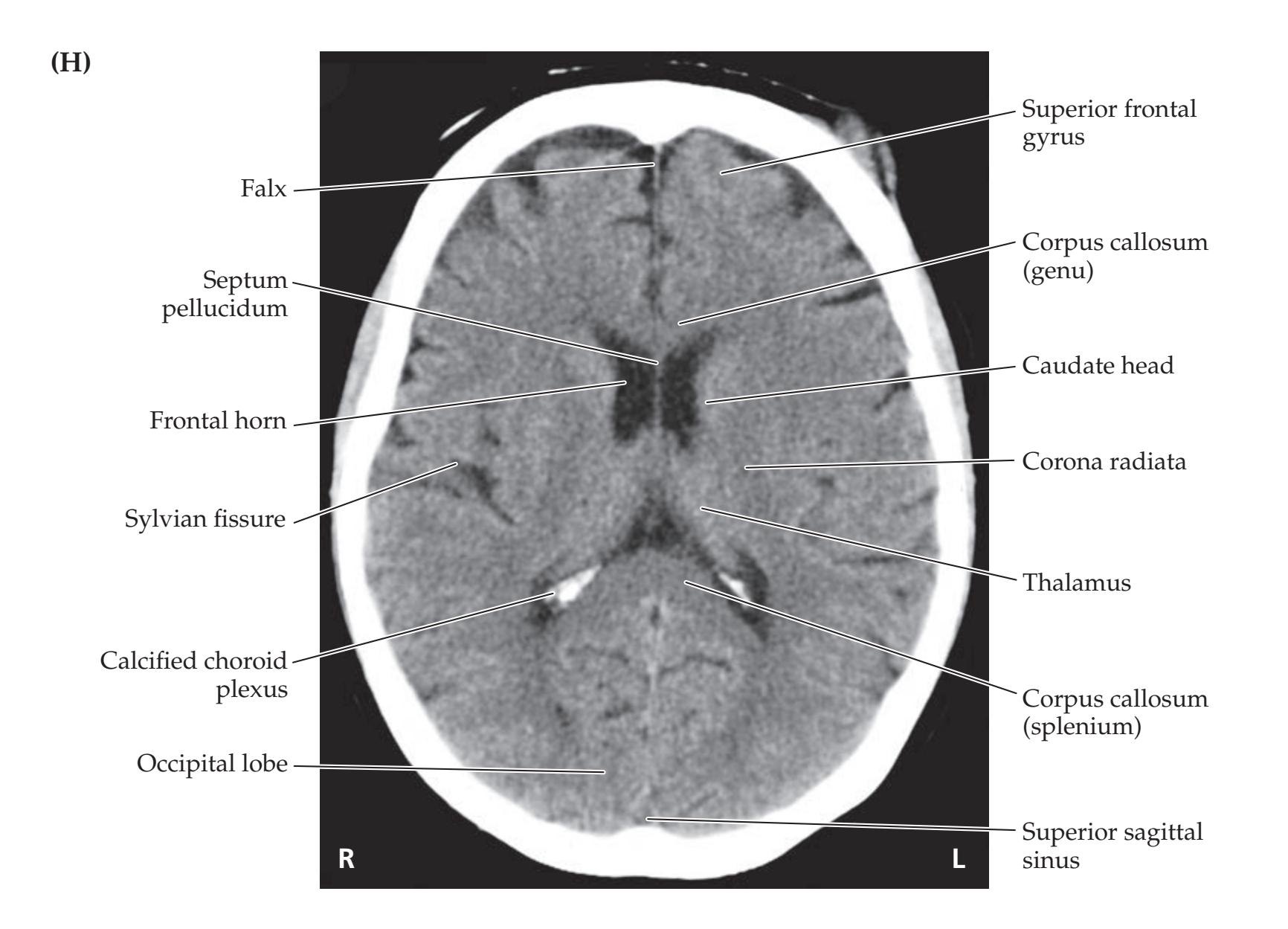

**Introduction 86 Imaging Planes 86 Computed Tomography 86 CT versus MRI 89**

**Magnetic Resonance Imaging 90**

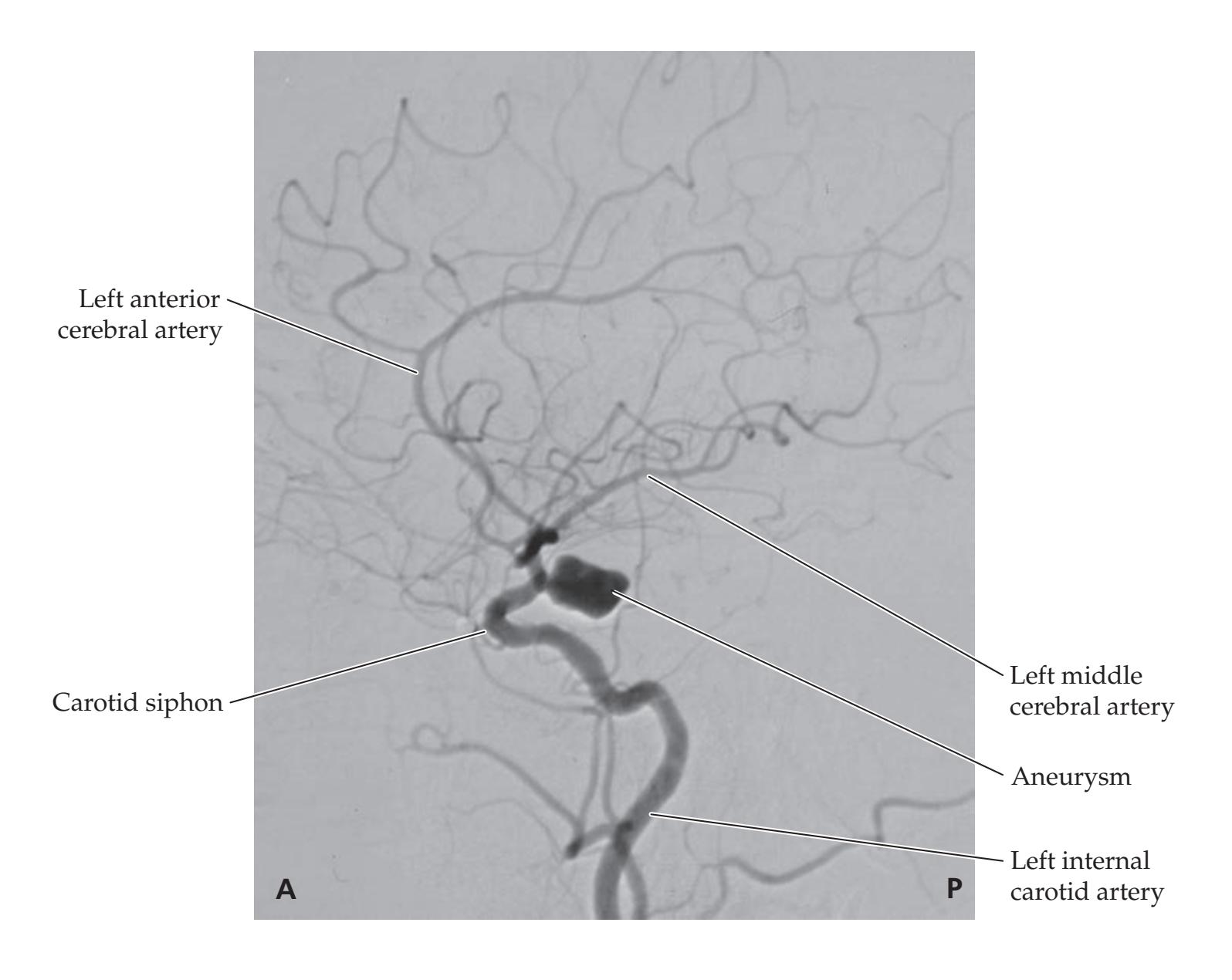

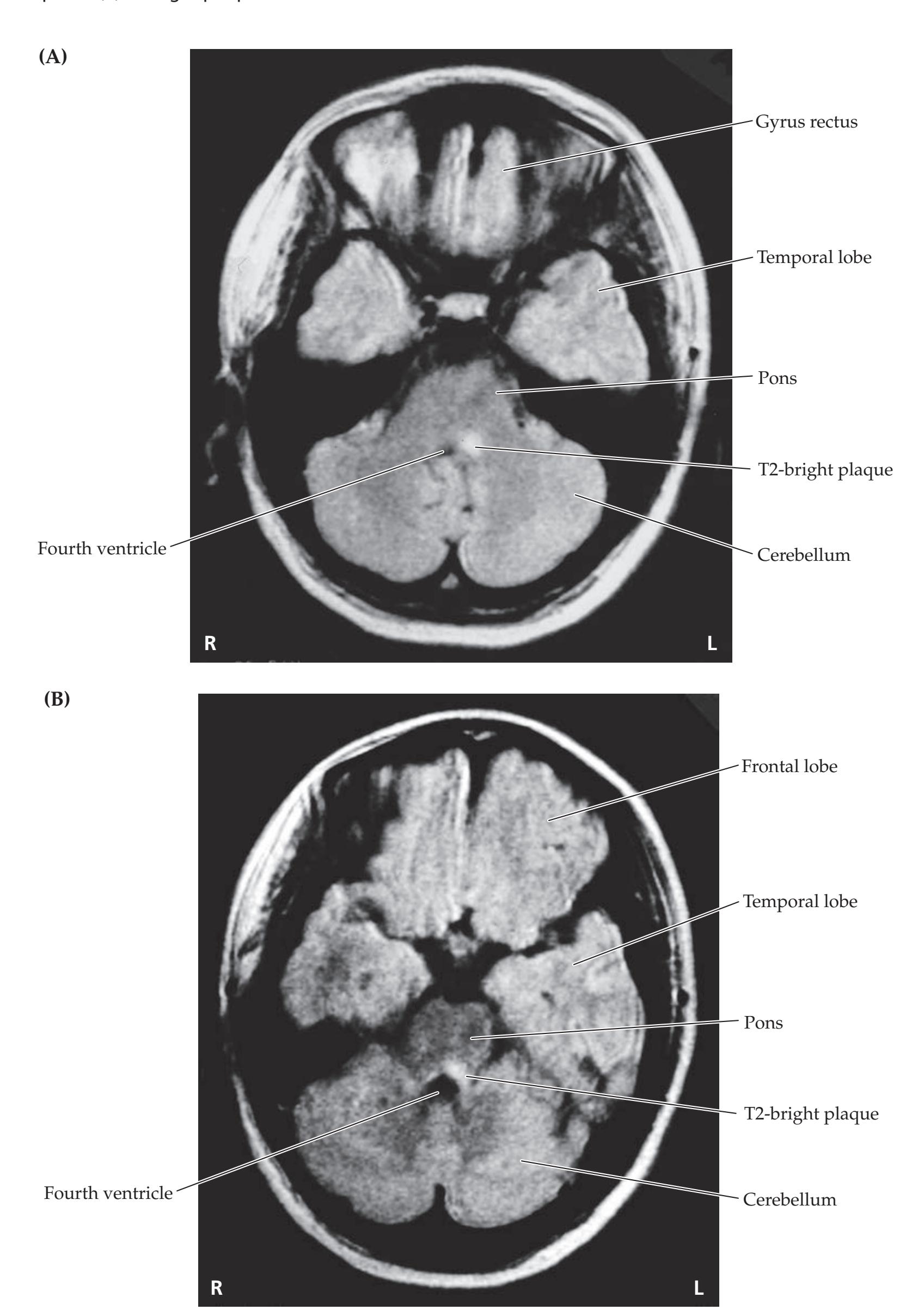

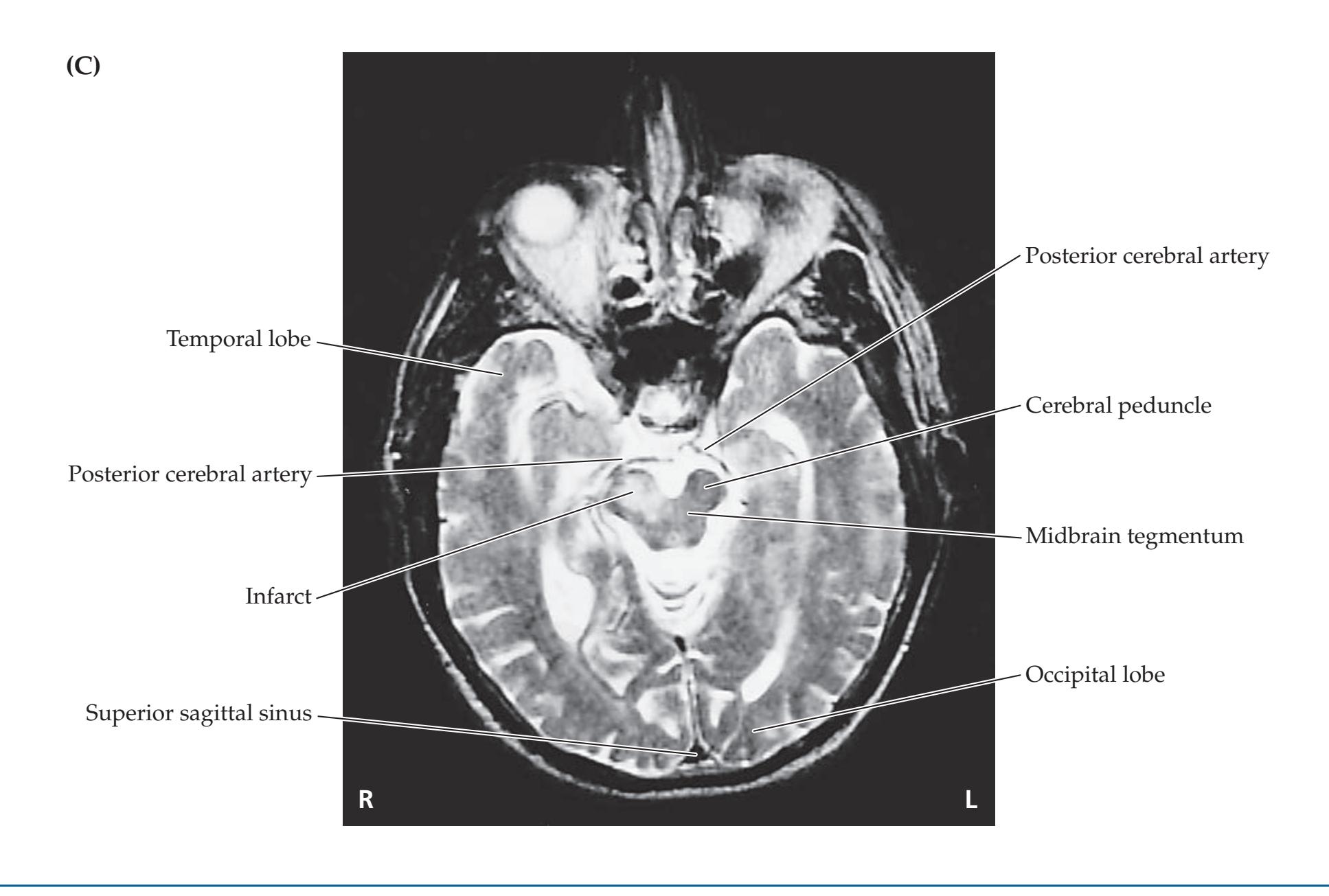

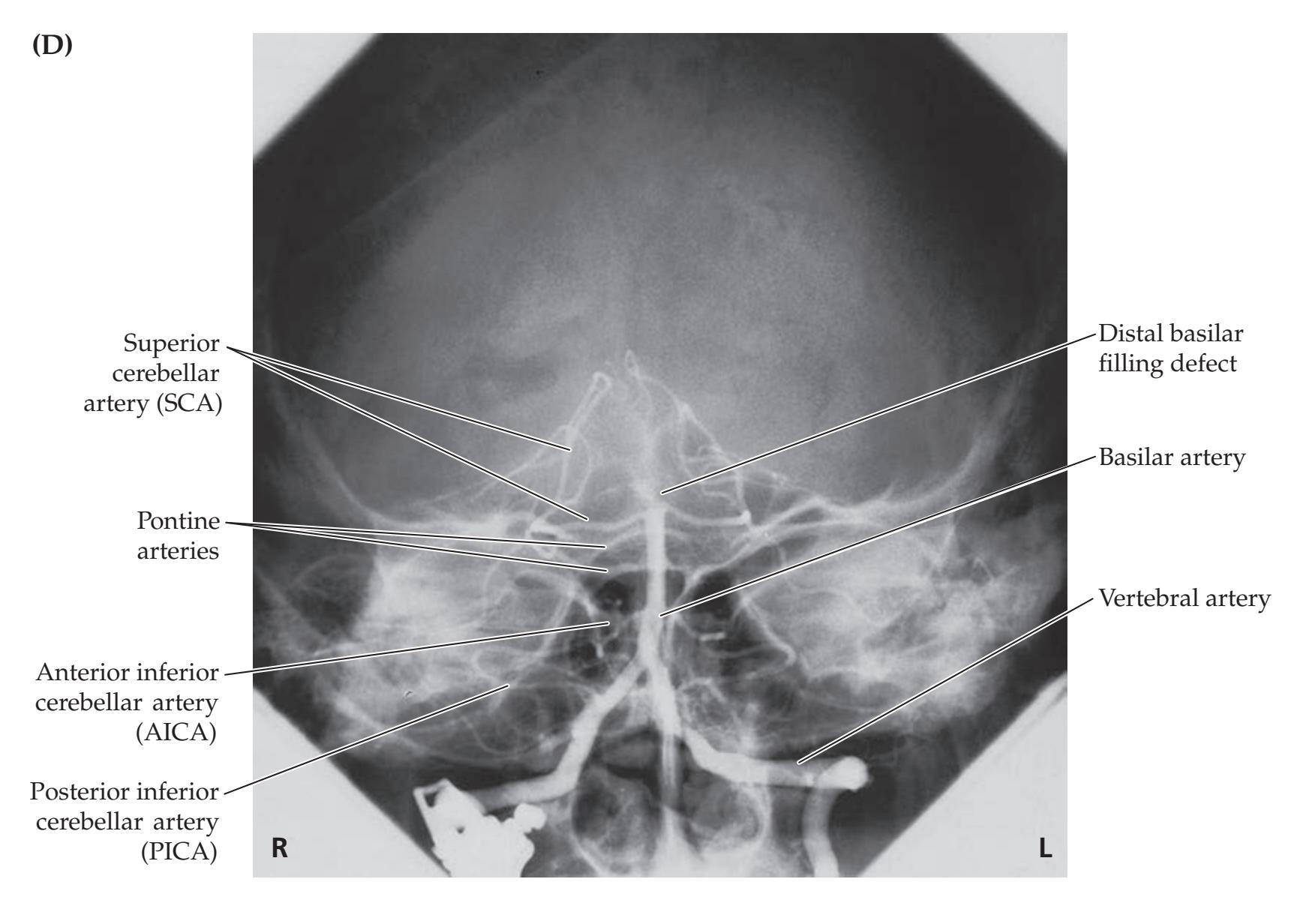

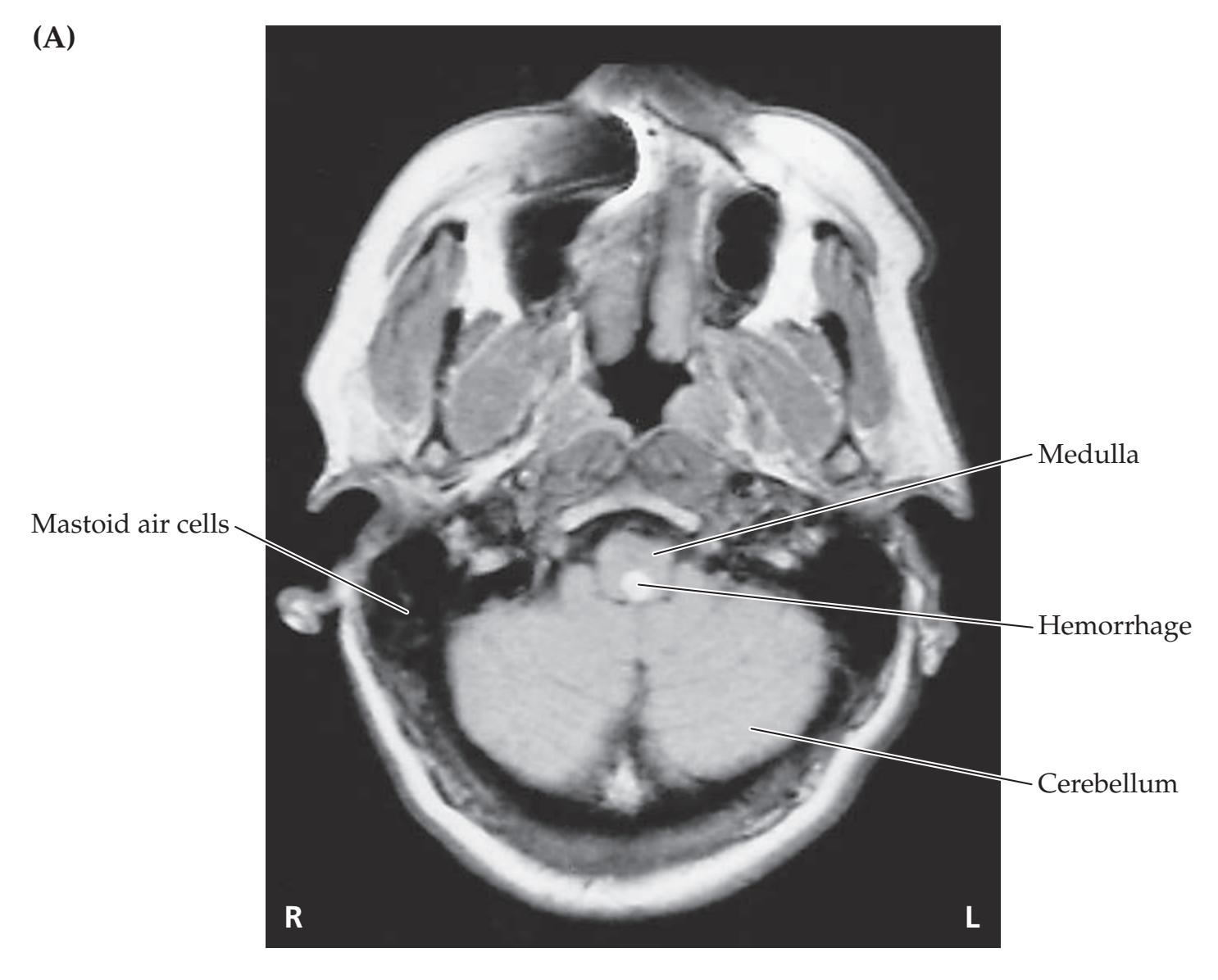

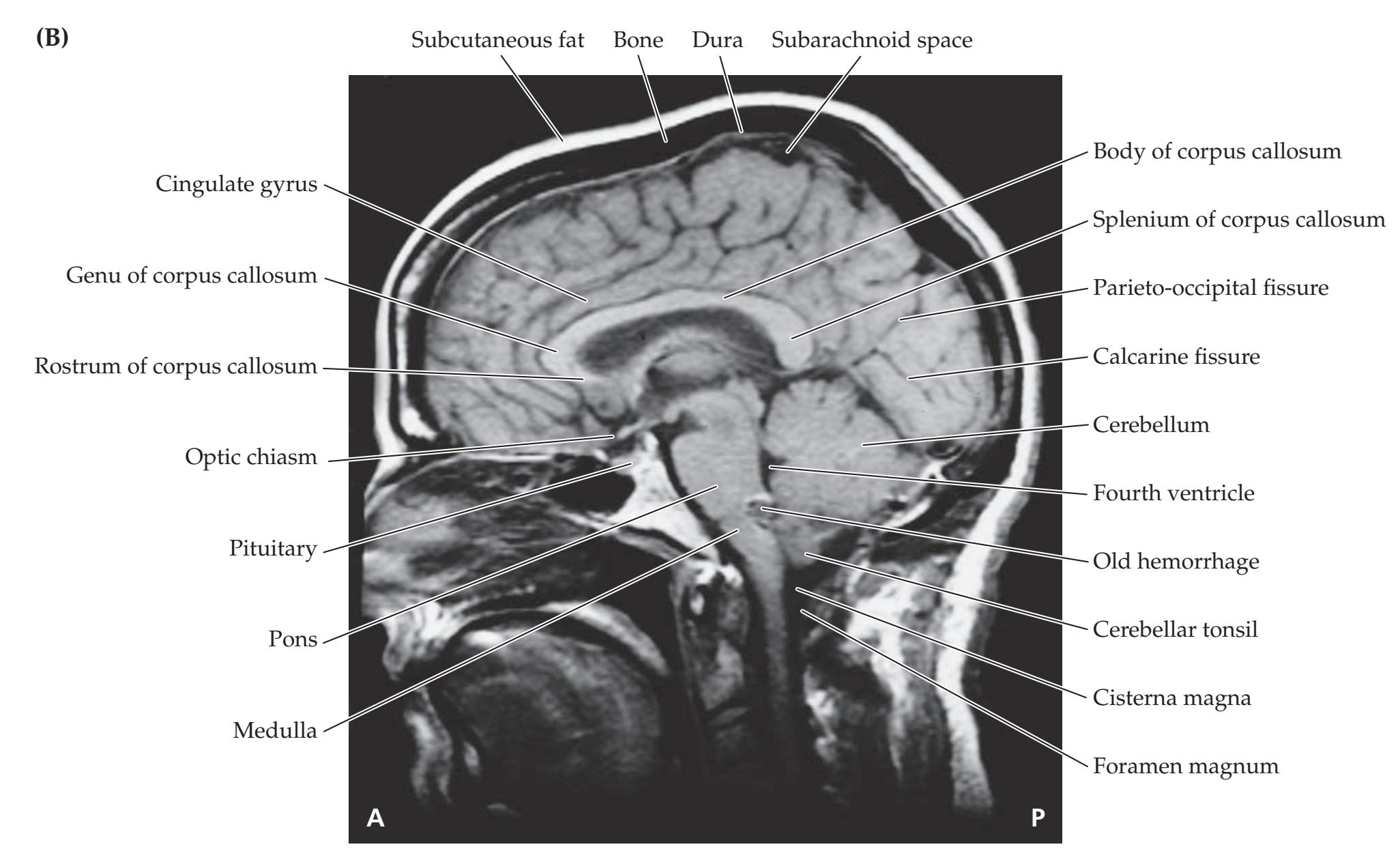

**Neuroangiography 98 Functional Neuroimaging 100 Conclusions 101 NEURORADIALOGICAL ATLAS 102**

**References 123**

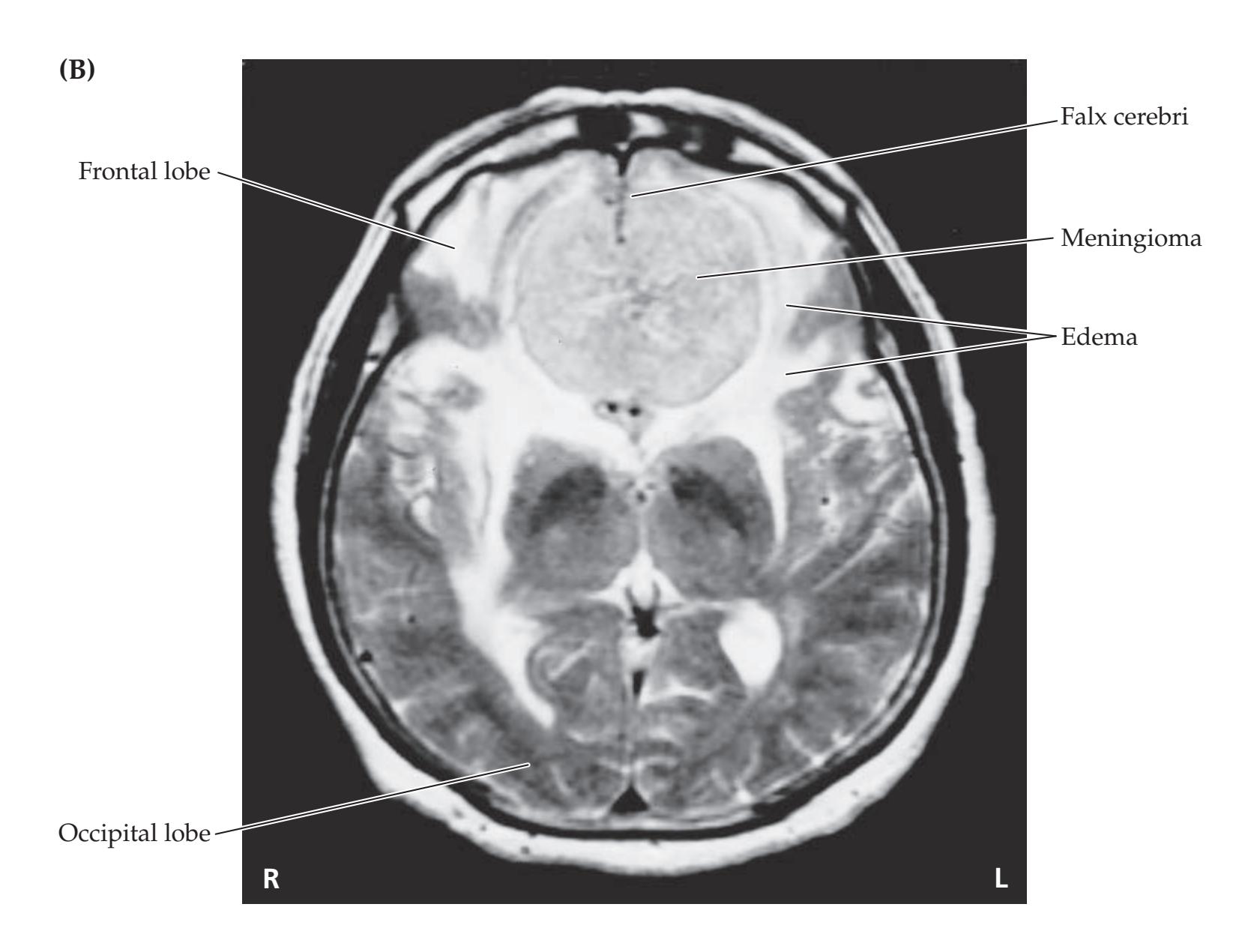

## Chapter 5 *Brain and Environs: Cranium, Ventricles, and Meninges 125*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 126**

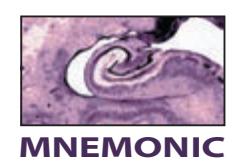

**Cranial Vault and Meninges 126**

**Ventricles and Cerebrospinal Fluid 132**

**Blood–Brain Barrier 137**

- **KCC 5.1** Headache 139

- **KCC 5.2** Intracranial Mass Lesions 141

- **KCC 5.3** Elevated Intracranial Pressure 142

- **KCC 5.4** Brain Herniation Syndromes 145

- **KCC 5.5** Head Trauma 147

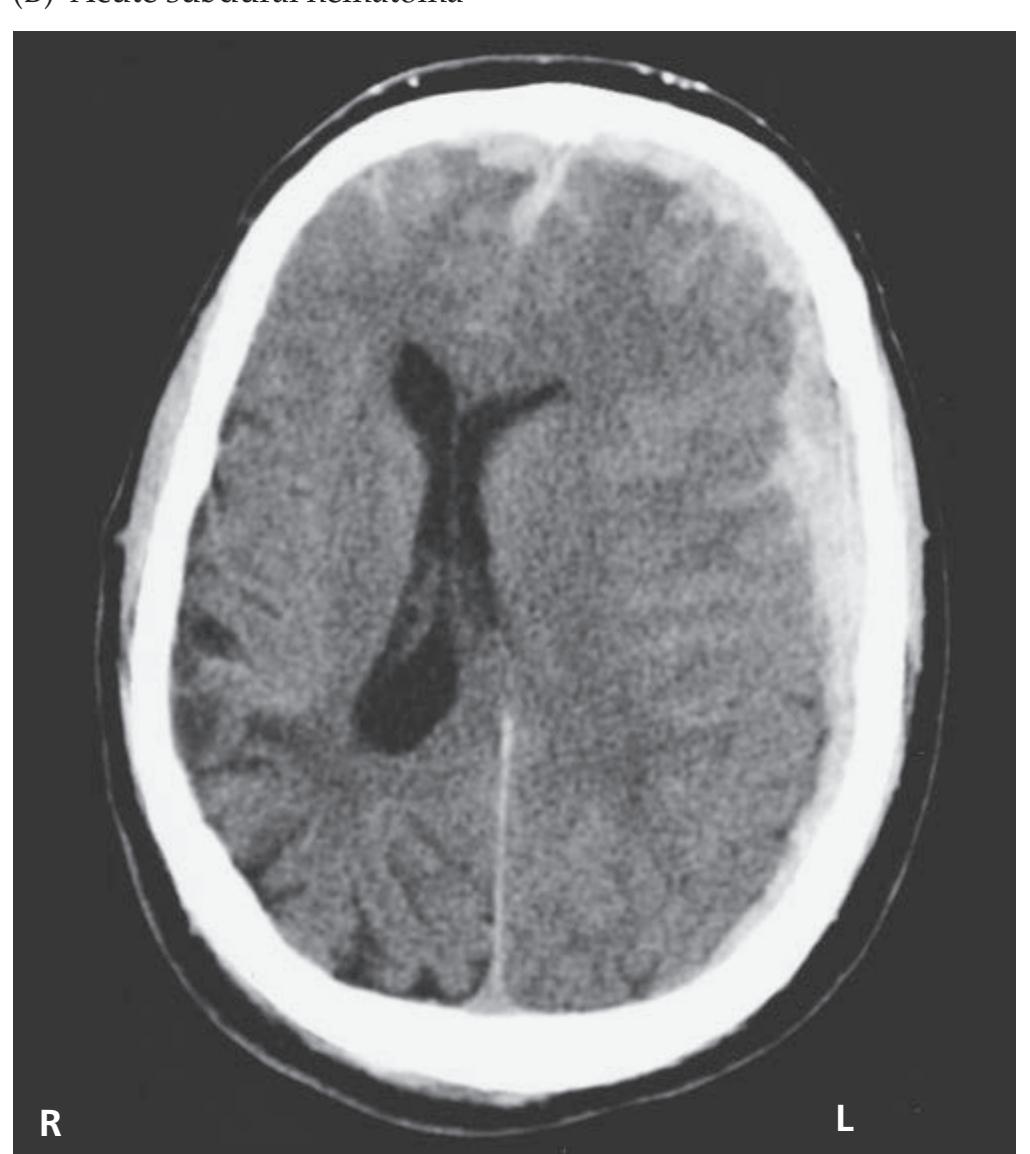

- **KCC 5.6** Intracranial Hemorrhage 148

- **KCC 5.7** Hydrocephalus 156

- **KCC 5.8** Brain Tumors 158

- **KCC 5.9** Infectious Disorders of the Nervous System 160

- **KCC 5.10** Lumbar Puncture 167

- **KCC 5.11** Craniotomy 169

### **CLINICAL CASES 170**

- **5.1** An Elderly Man with Headaches and Unsteady Gait 170

- **5.2** Altered Mental Status Following Head Injury 173

- **5.3** Delayed Unresponsiveness after Head Injury 180

- **5.4** Headache and Progressive Left-Sided Weakness 183

- **5.5** Sudden Coma and Bilateral Posturing during Intravenous Anticoagulation 187

- **5.6** Severe Head Injury 190

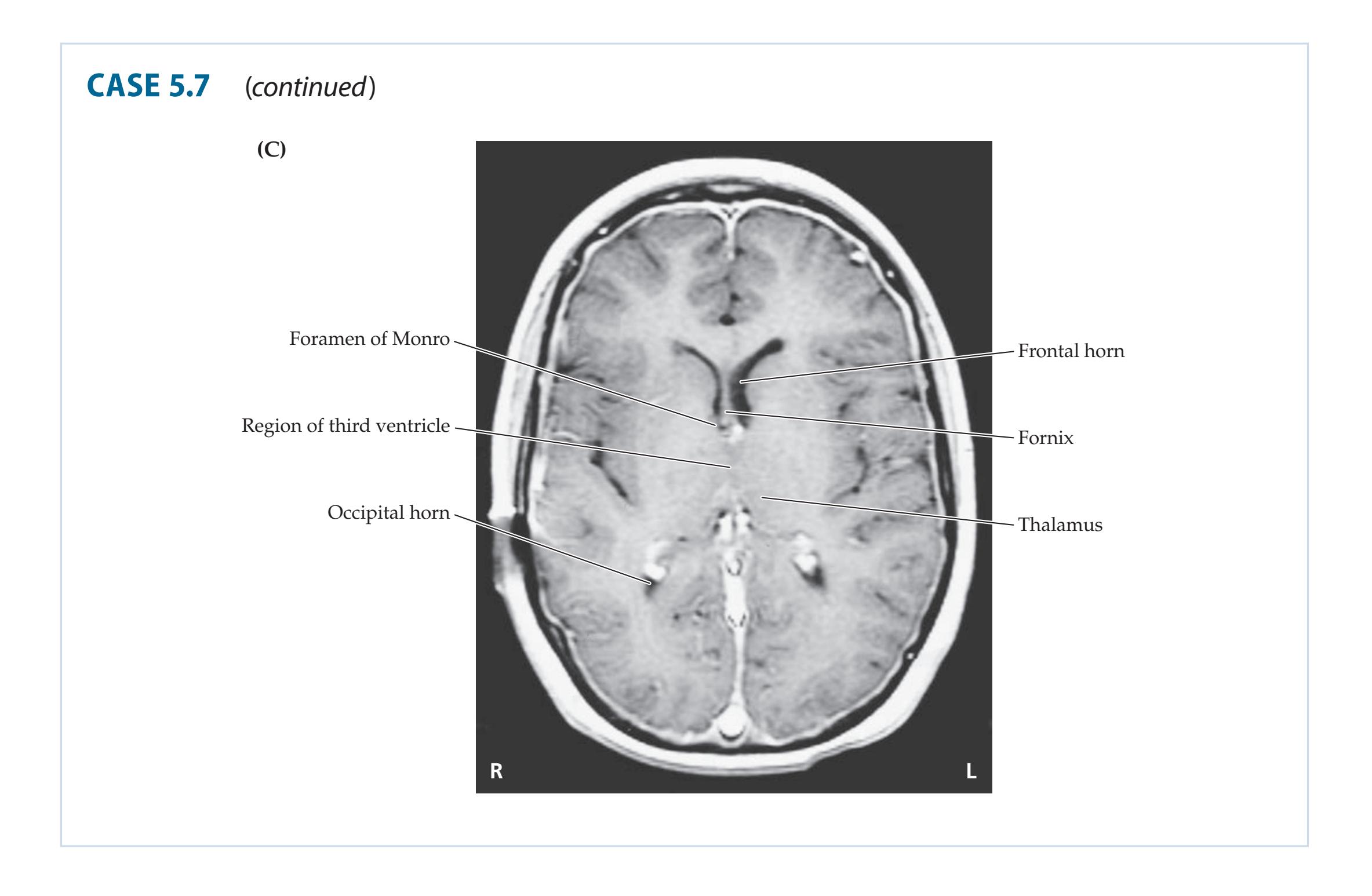

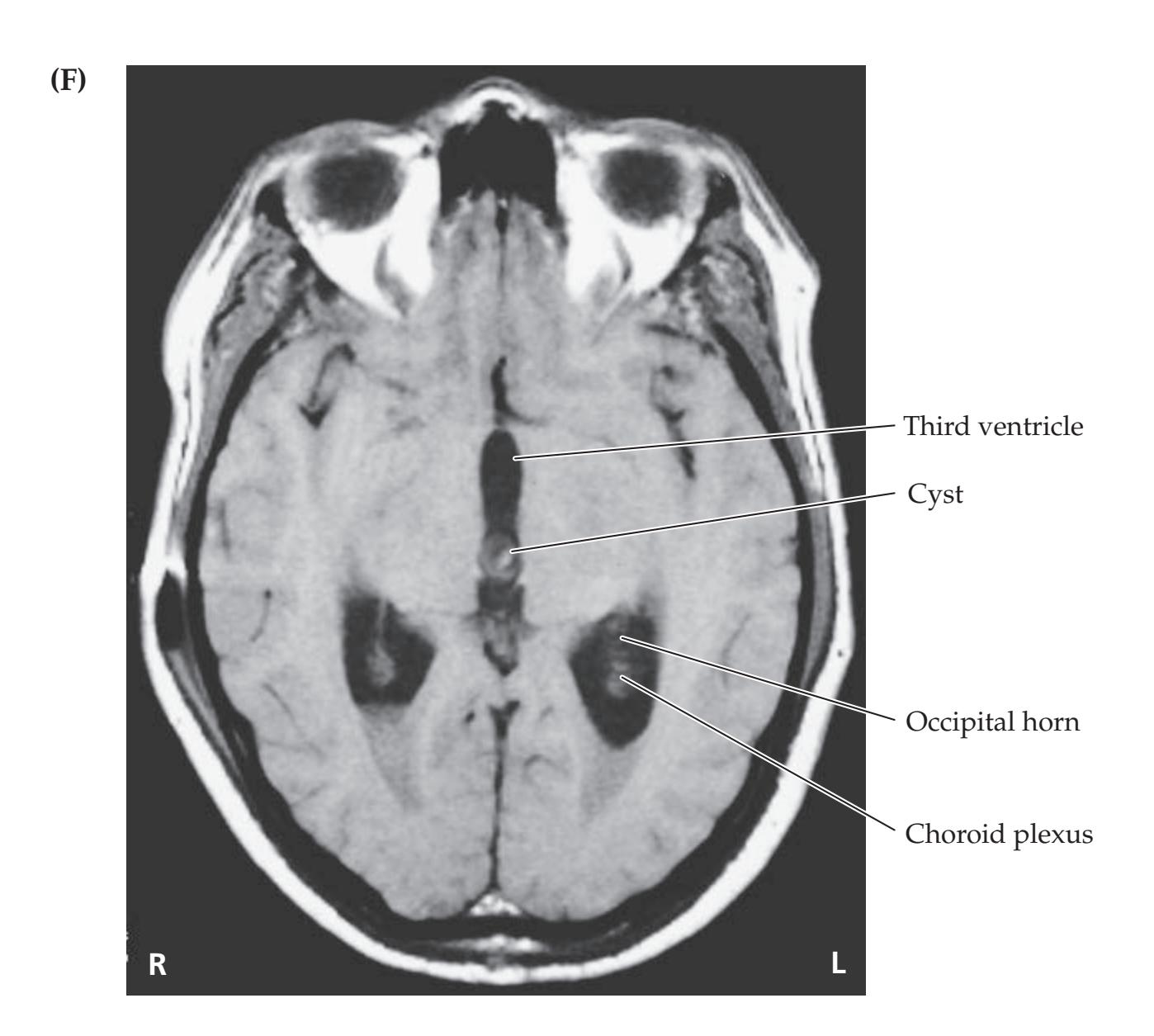

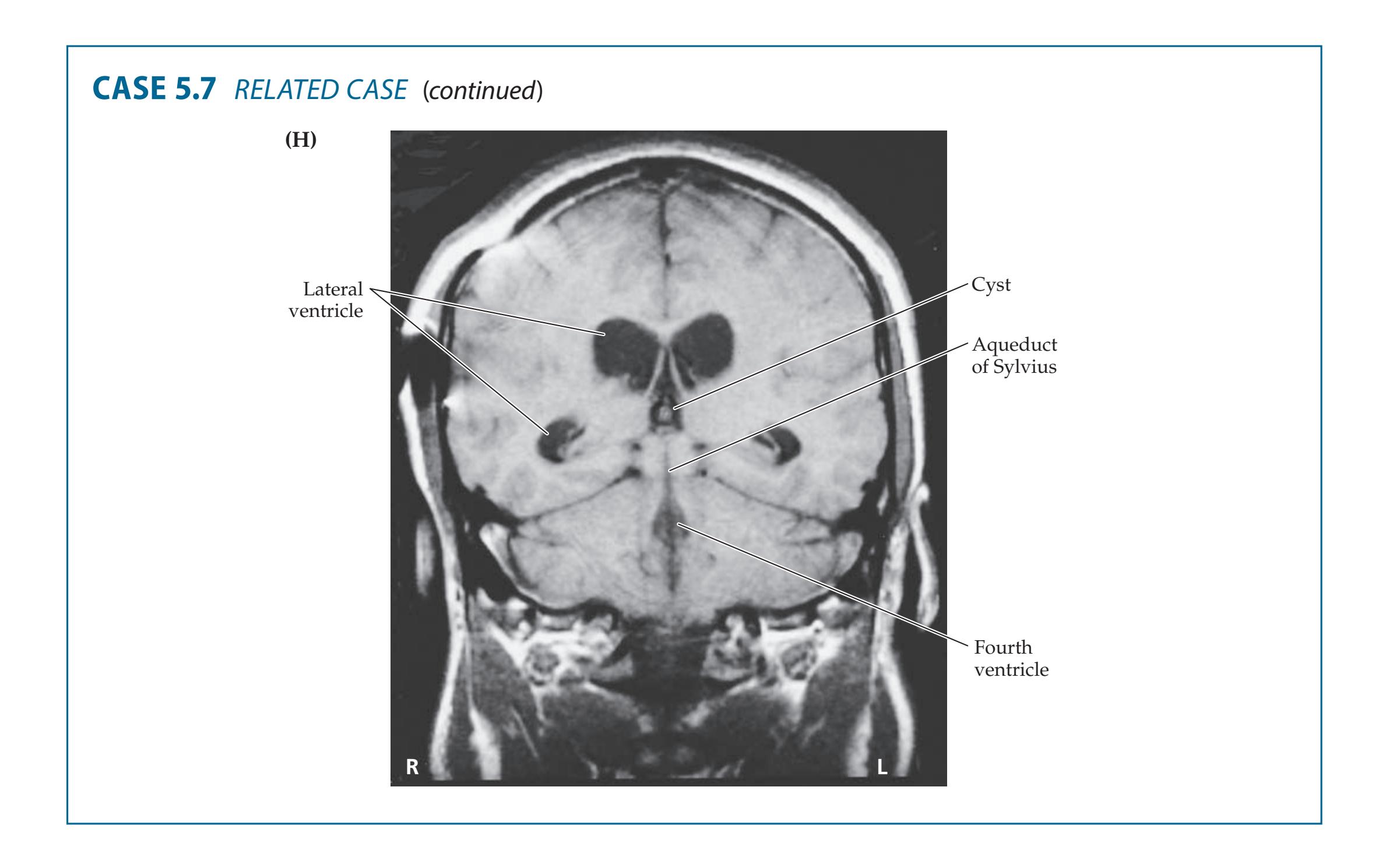

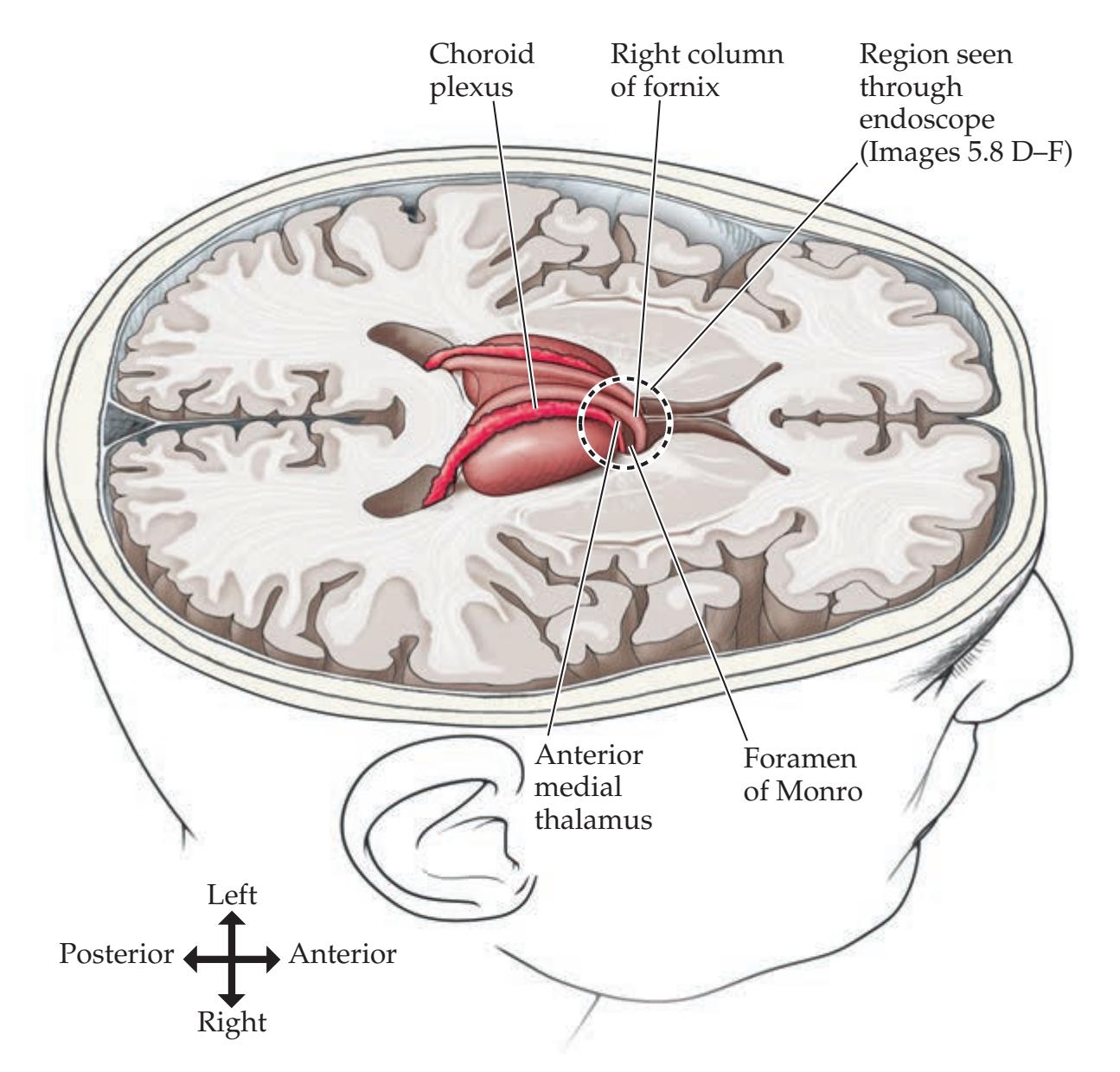

- **5.7** A Child with Headaches, Nausea, and Diplopia 195

- **5.8** Headaches and Progressive Visual Loss 203

- **5.9** An Elderly Man with Progressive Gait Difficulty, Cognitive Impairment, and Incontinence 208

- **5.10** A Young Man with Headache, Fever, Confusion, and Stiff Neck 212

**Additional Cases 213**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 214**

**A Scuba Expedition through the Brain 215**

**References 217**

Contents **ix**

## Chapter 6 *Corticospinal Tract and Other Motor Pathways 221*

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW | | | | 222 |

|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|--|--|-----|

| 8.3

Unilateral Shoulder Pain and Weakness

335 | 8.9

Unilateral Thigh Weakness with Pain Radiating to | | | |

| 8.4

Blisters, Pain, and Weakness in the Left Arm

338 | the Anterior Shin

343 | | | |

| 8.5

Unilateral Shoulder Pain and Numbness in the Index | 8.10

Low Back Pain Radiating to the Big Toe

346 | | | |

| and Middle Fingers

339 | 8.11

Saddle Anesthesia with Loss of Sphincteric and | | | |

| 8.6

Unilateral Neck Pain, Hand Weakness, and Numbness | Erectile Function

347 | | | |

| in the Ring and Little Fingers

340 | Additional Cases

349 | | | |

| 8.7

Pain and Numbness in the Medial Arm

341

8.8

Low Back Pain Radiating to the Sole of the Foot | BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE

349 | | | |

| and the Small Toe

341 | References

352 | | | |

| | | | | |

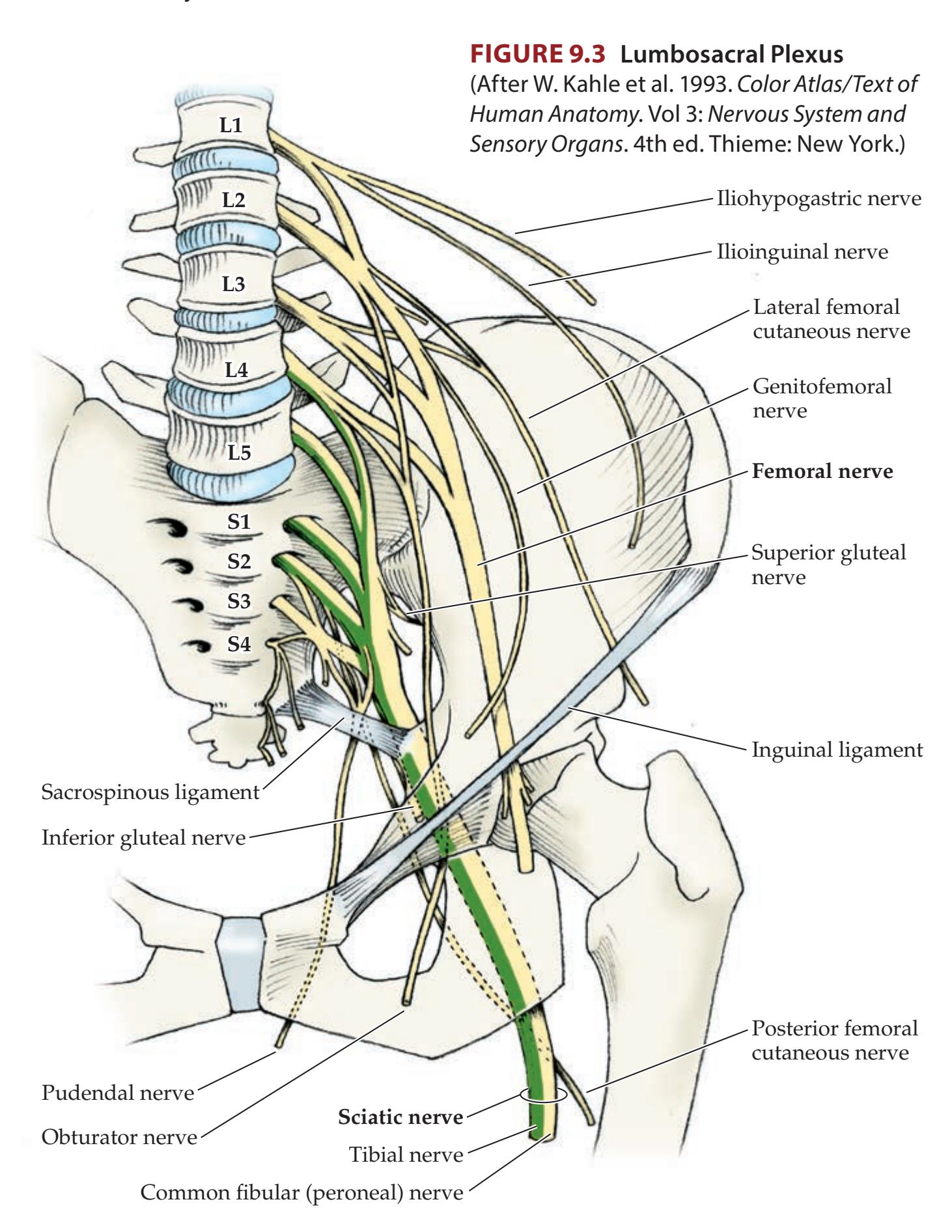

| Chapter 9

Major Plexuses and Peripheral Nerves | 355 | | | |

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW

356 | 9.4

Nocturnal Pain and Tingling in the Thumb, Pointer, | | | |

| Brachial Plexus and Lumbosacral Plexus

356 | and Middle Finger

371 | | | |

| Simplification: Five Nerves to Remember in | 9.5

Hand and Wrist Weakness after a Fall

372 | | | |

| the Arm

358 | 9.6

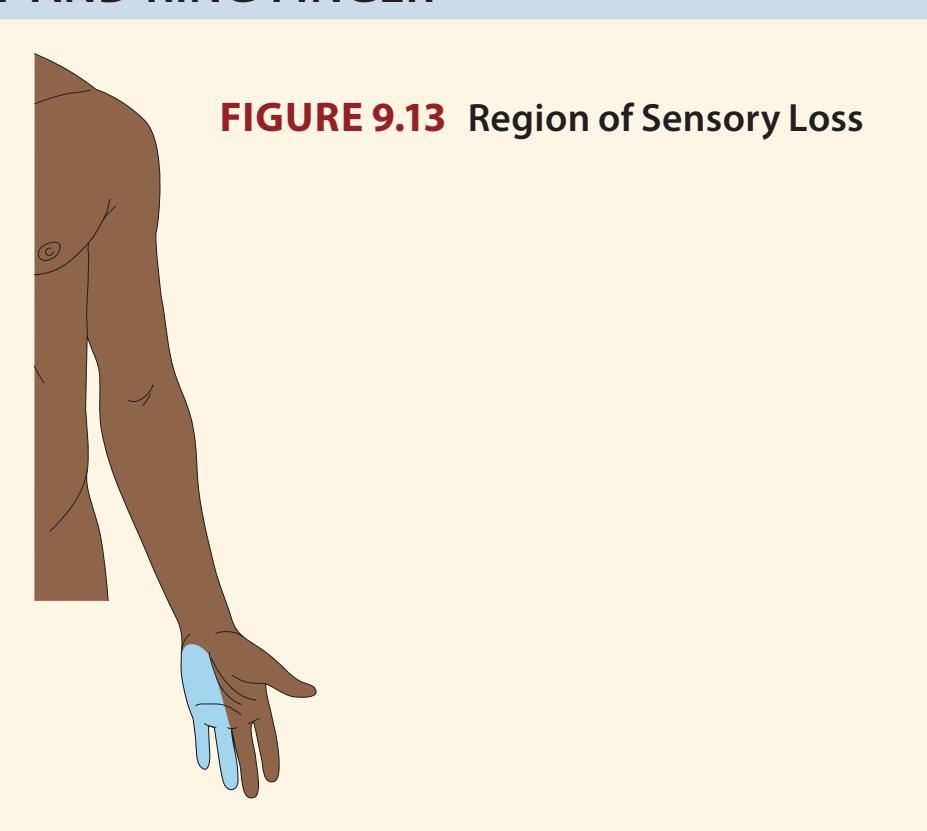

Numbness and Tingling in the Pinky and

Ring Finger

373 | | | |

| Simplification: Three Nerves Acting on

the Thumb

360 | 9.7

Shoulder Weakness and Numbness after

Strangulation

374 | | | |

| Intrinsic and Extrinsic Hand Muscles

360 | 9.8

Unilateral Thigh Pain, Weakness, and Numbness | | | |

| Simplification: Five Nerves to Remember in | in a Diabetic

375 | | | |

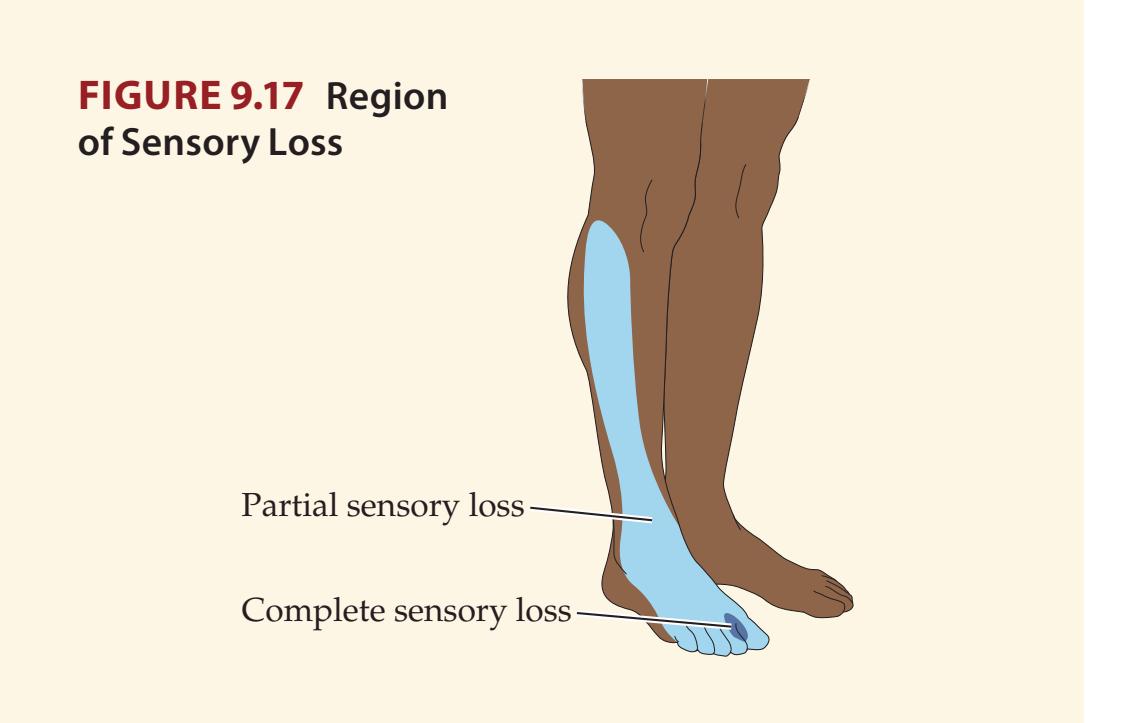

| the Leg

361 | 9.9

Tingling and Paralysis of the Foot after a Fall

375 | | | |

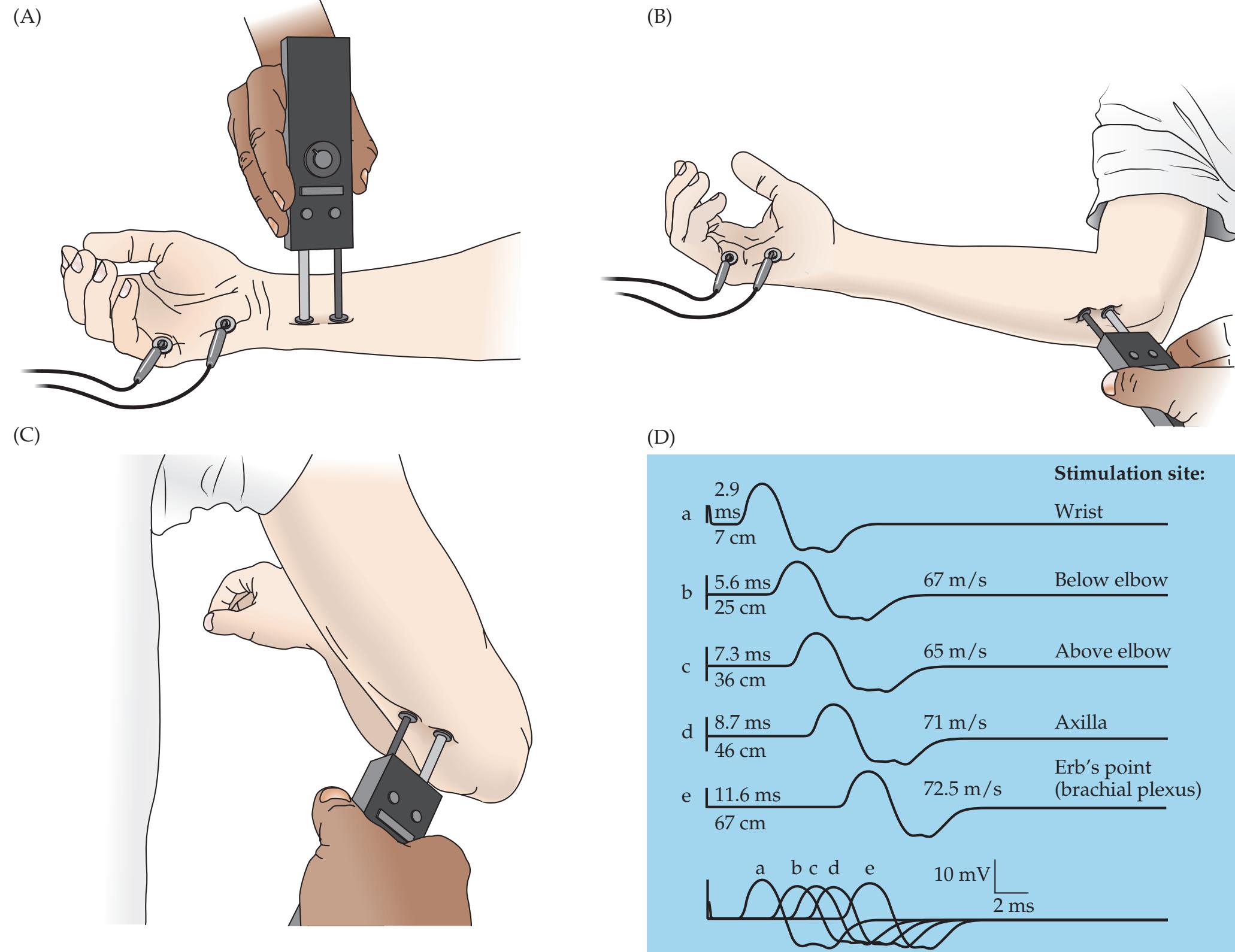

| KCC 9.1

Common Plexus and Nerve Syndromes

362 | 9.10

A Leg Injury Resulting in Foot Drop

377 | | | |

| KCC 9.2

Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction | 9.11

Lateral Thigh Pain and Numbness after Pregnancy

379 | | | |

| Studies

365 | 9.12

Dysarthria, Ptosis, and Decreased Exercise | | | |

| CLINICAL CASES

367 | Tolerance

379

9.13

Generalized Weakness and Areflexia

381 | | | |

| 9.1

Complete Paralysis and Loss of Sensation in | 9.14

Mysterious Weakness after Dinner

383 | | | |

| One Arm

367 | | | | |

| 9.2

A Newborn with Weakness in One Arm

369 | Additional Cases

384 | | | |

| 9.3

A Blow to the Medial Arm Causing Hand Weakness | BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE

384 | | | |

| and Numbness

370 | References

385 | | | |

| | | | | |

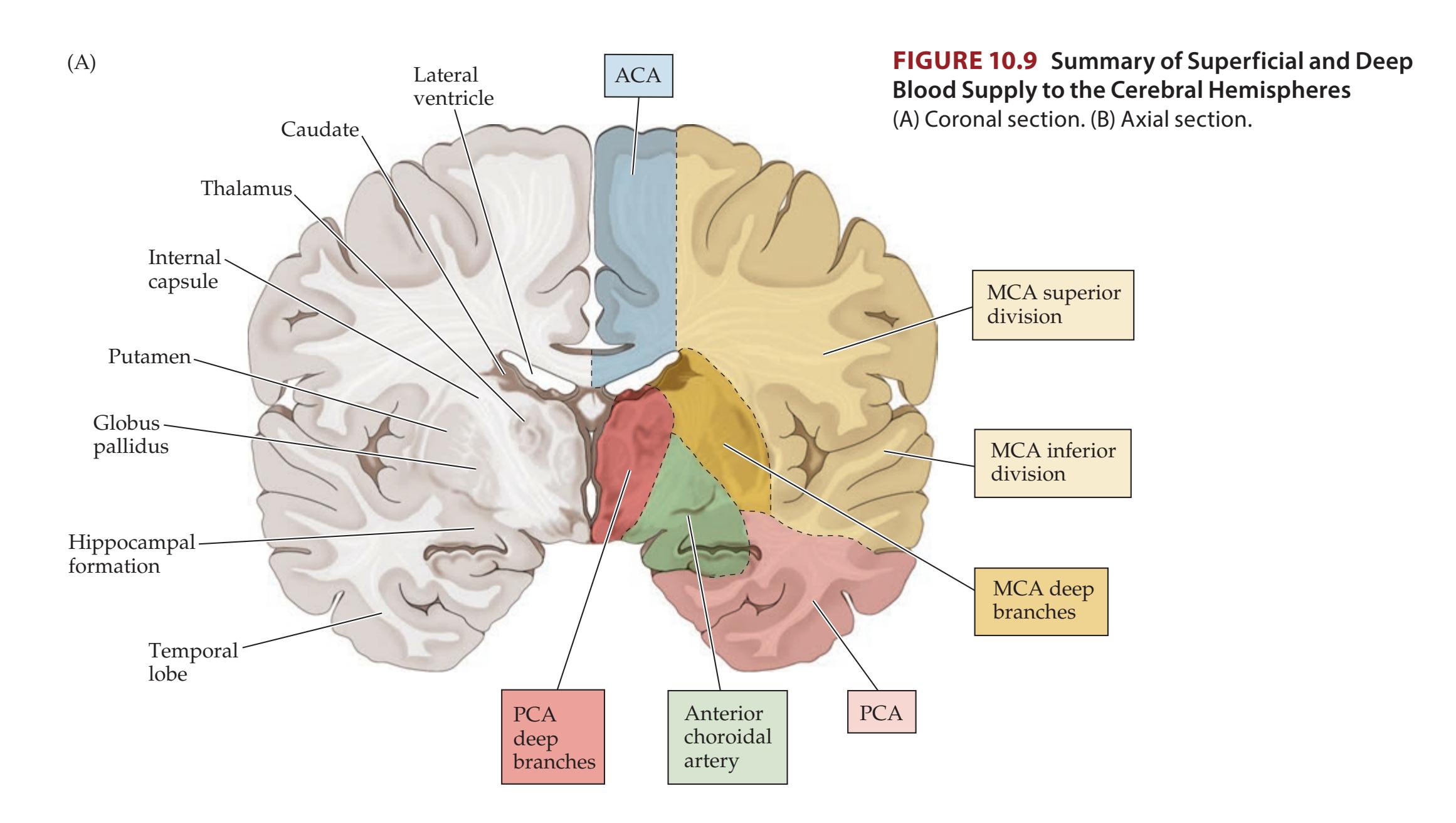

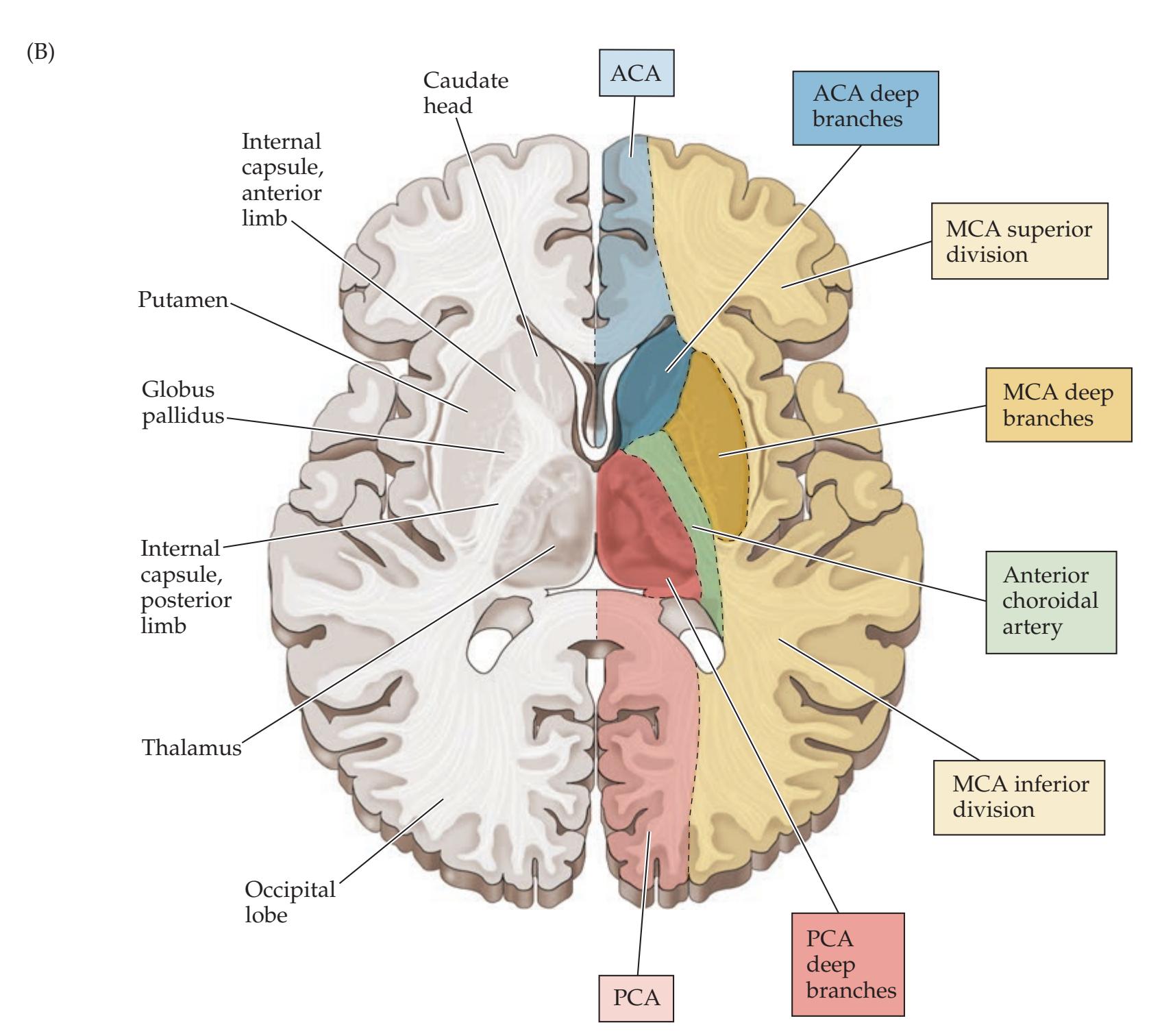

| Chapter 10

Cerebral Hemispheres and Vascular Supply | 389 | | | |

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW

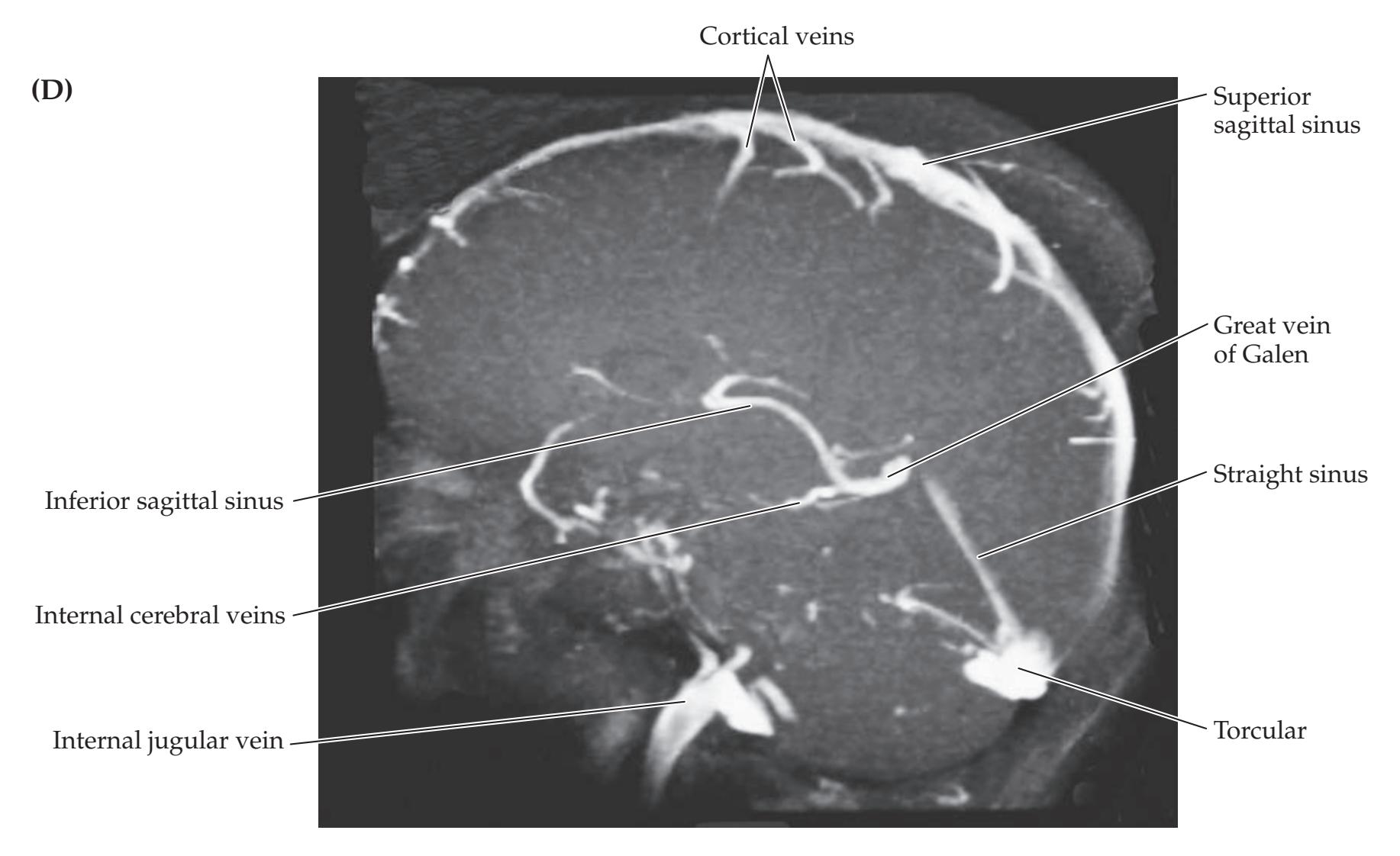

390 | Venous Drainage of the Cerebral | | | |

| Review of Main Functional Areas of Cerebral | Hemispheres

409 | | | |

| Cortex

390 | KCC 10.7

Sagittal Sinus Thrombosis

418 | | | |

| Circle of Willis: Anterior and Posterior | CLINICAL CASES

411 | | | |

| Circulations

391 | 10.1

Sudden-Onset Worst Headache of Life

411 | | | |

| Anatomy and Vascular Territories of the | 10.2

Left Leg Weakness and Left Alien Hand Syndrome

413 | | | |

| Three Main Cerebral Arteries

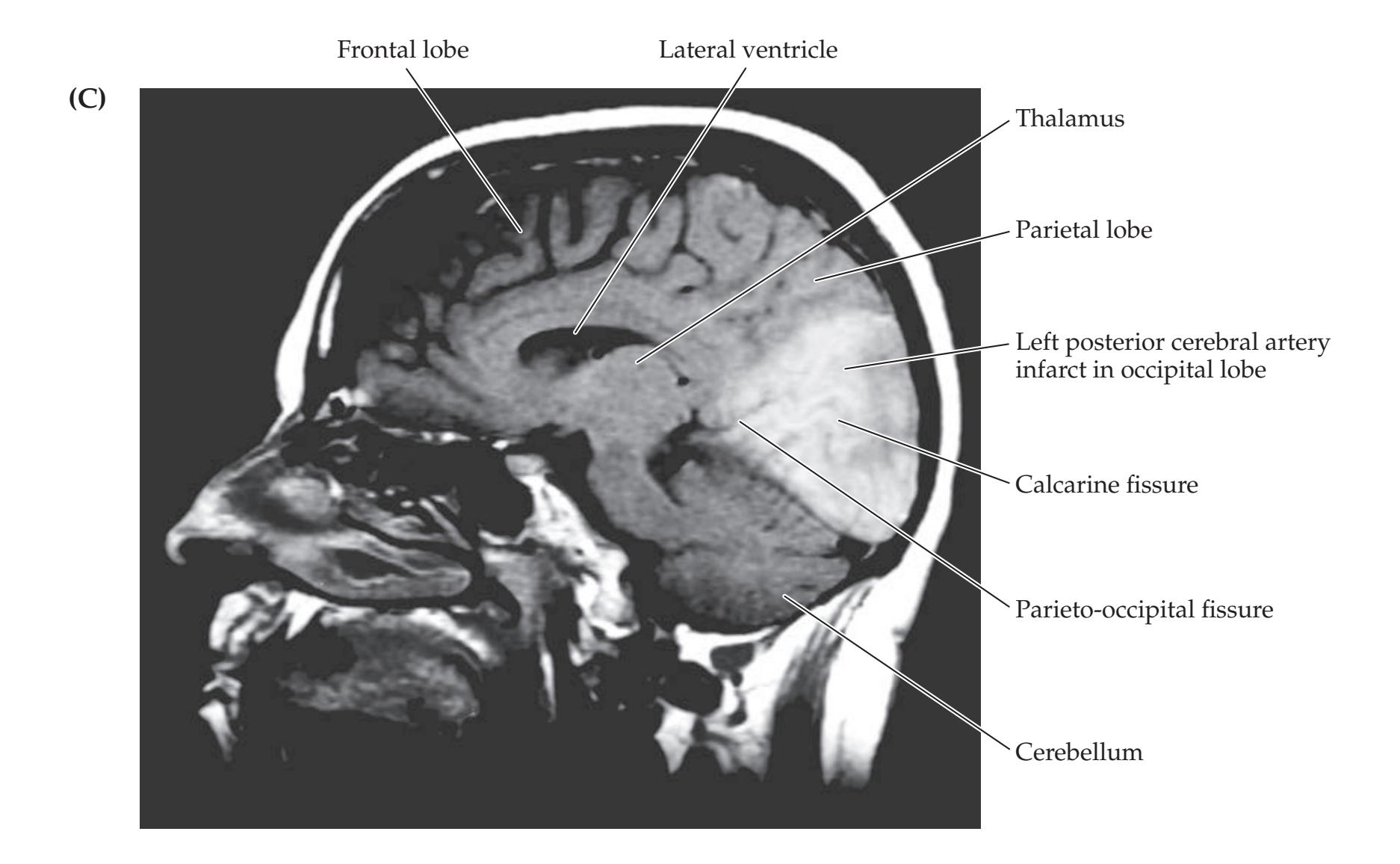

393 | 10.3

Decreased Vision on One Side

414 | | | |

| KCC 10.1

Clinical Syndromes of the Three Cerebral

Arteries

398 | 10.4

Transient Episodes of Left Eye Blurriness or

Right Hand Weakness

423 | | | |

| KCC 10.2

Watershed Infarcts

400 | 10.5

Nonfluent Aphasia with Right Face and | | | |

| KCC 10.3

Transient Ischemic Attack and Other Transient | Arm Weakness

425 | | | |

| Neurologic Episodes

401 | 10.6

"Talking Ragtime"

427 | | | |

| KCC 10.4

Ischemic Stroke: Mechanisms and Treatment

402 | 10.7

Dysarthria and Hemiparesis

430 | | | |

| KCC 10.5

Carotid Stenosis

408 | 10.8

Global Aphasia, Right Hemiplegia, | | | |

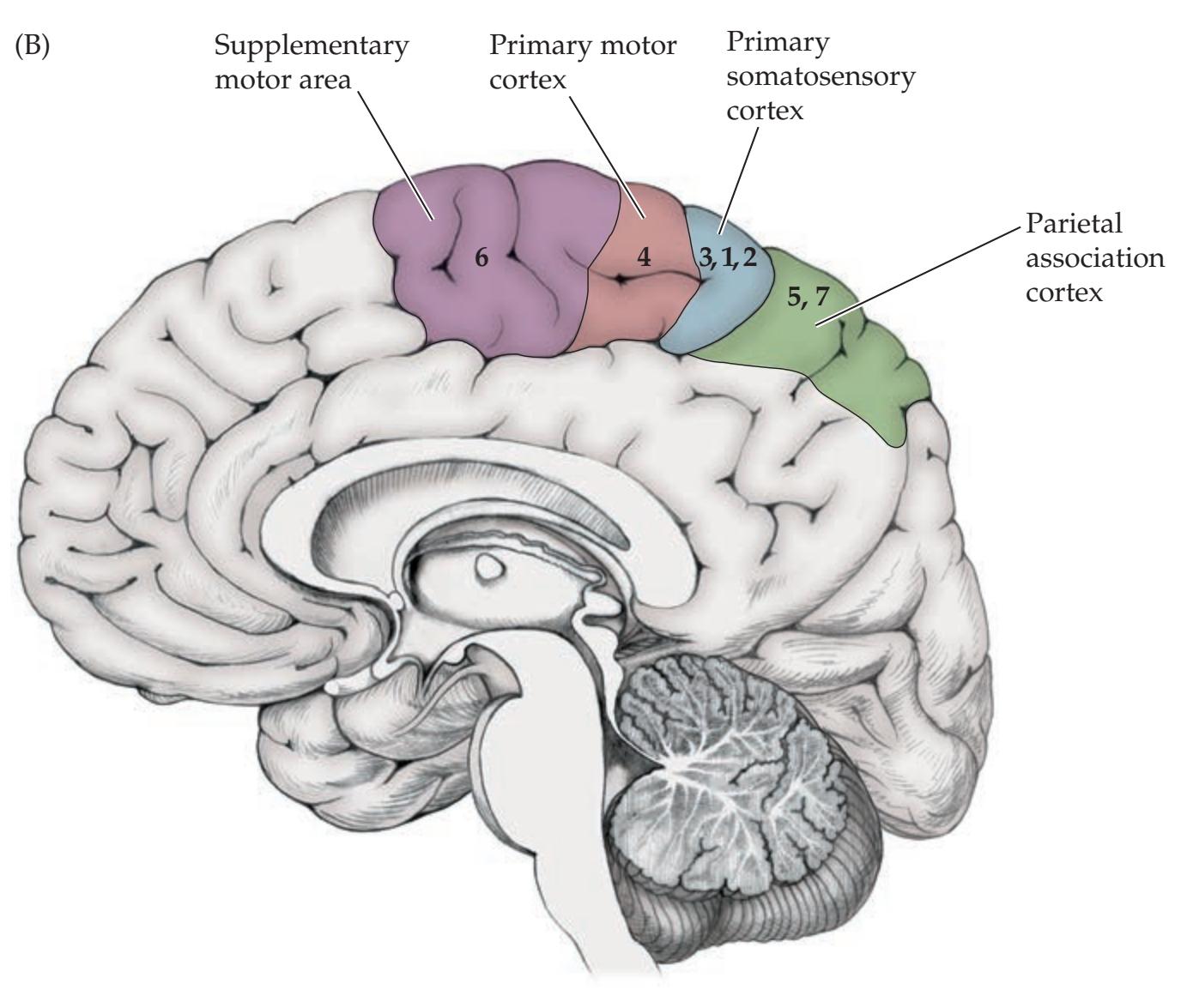

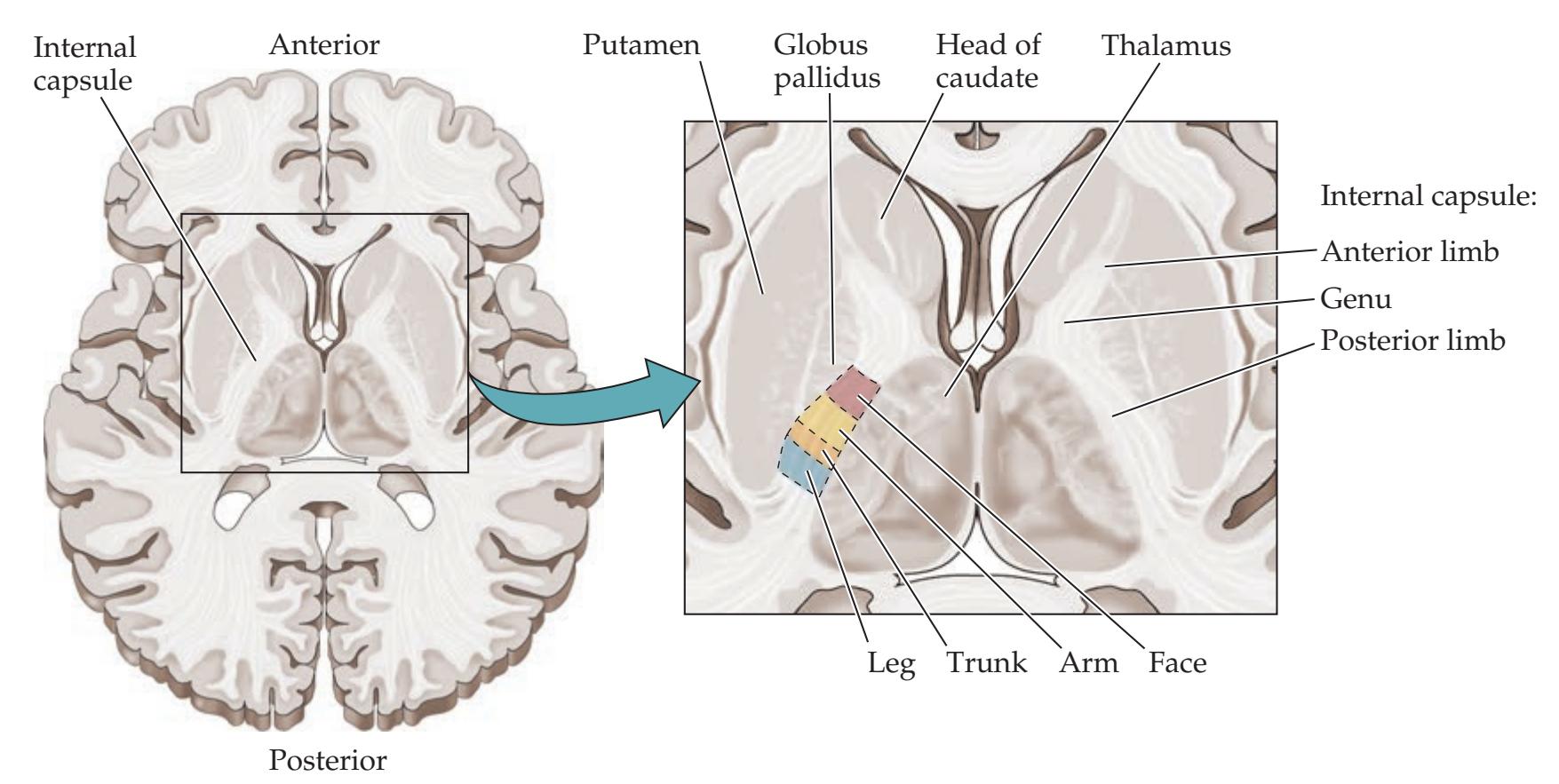

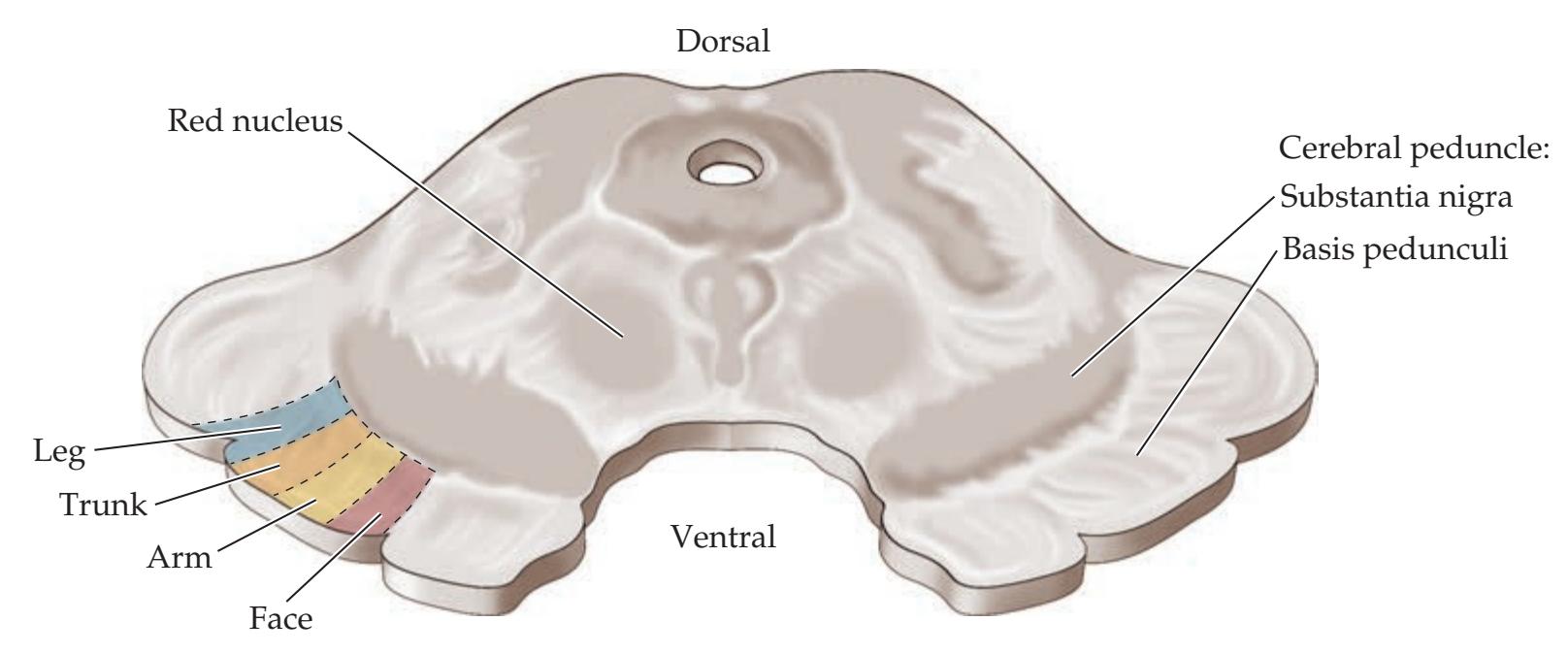

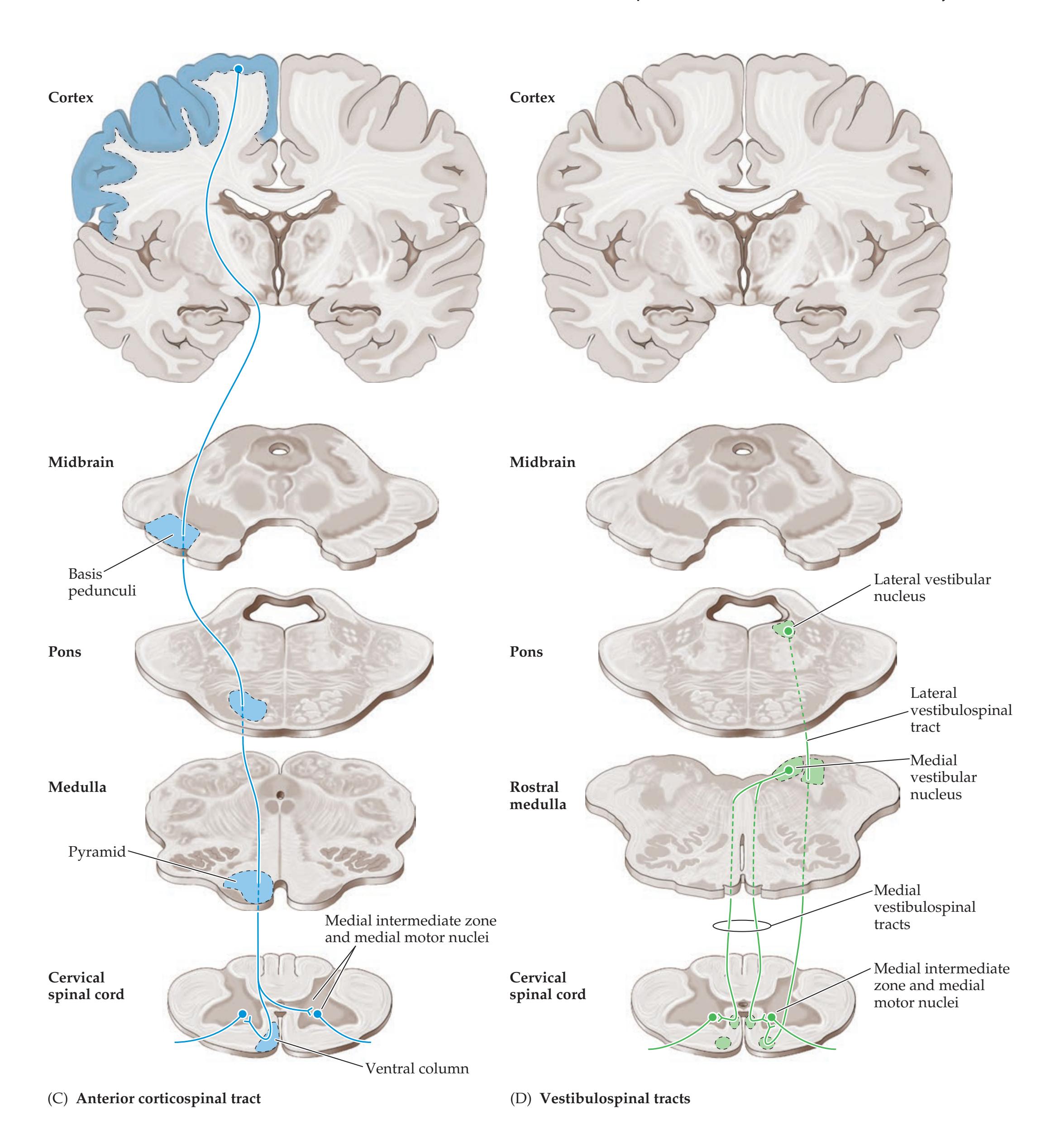

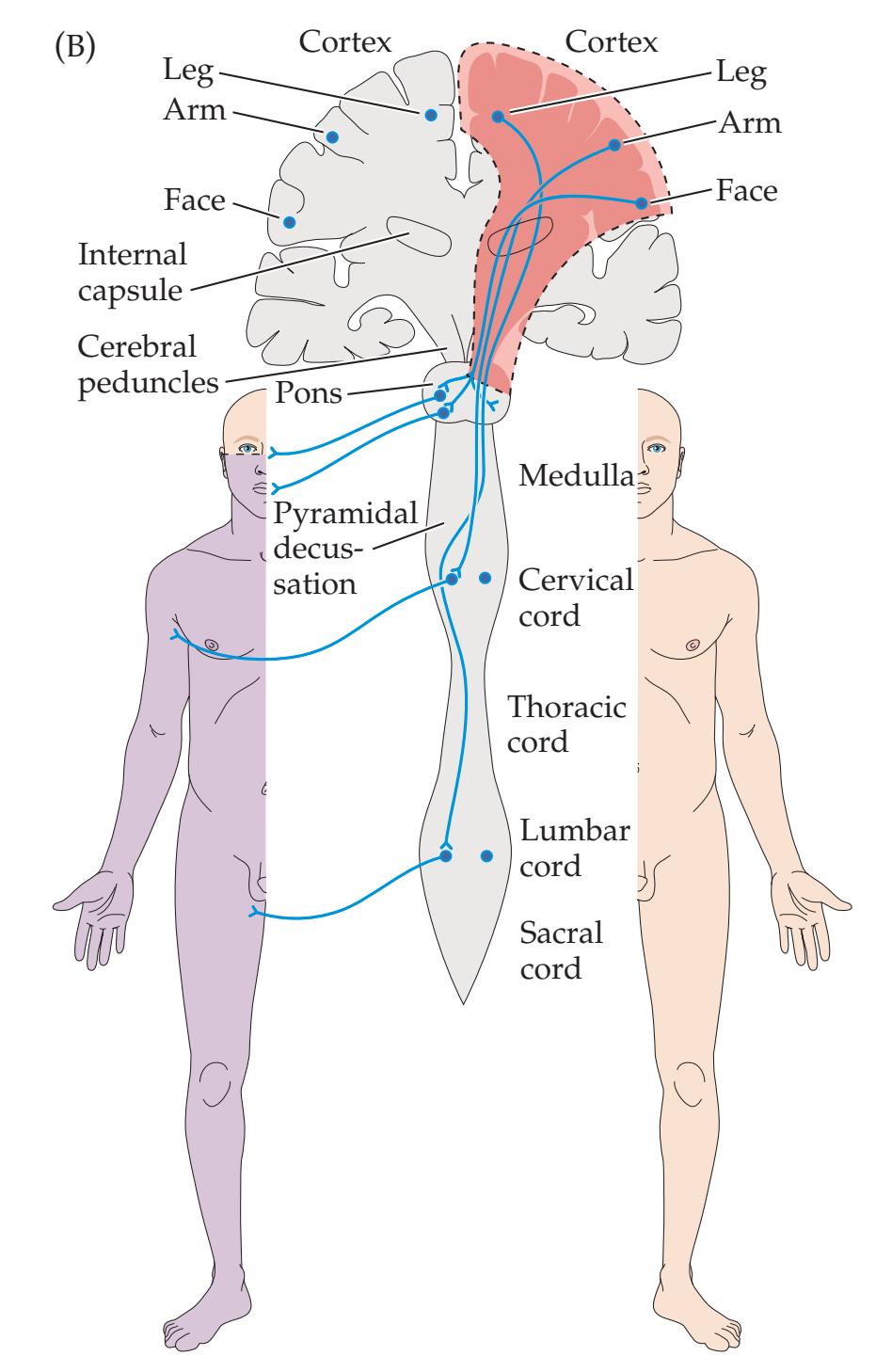

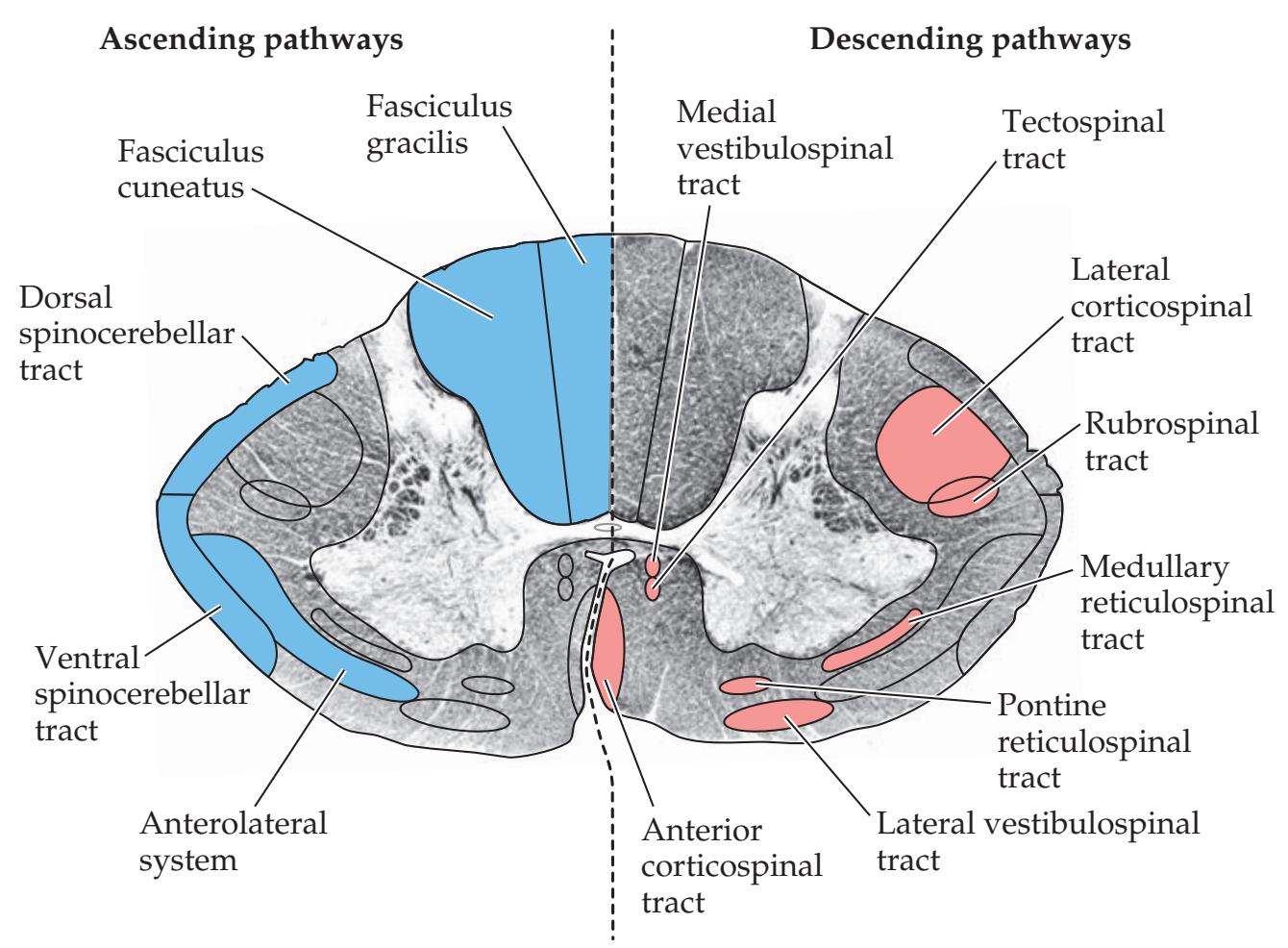

**Motor Cortex, Sensory Cortex, and Somatotopic Organization 222**

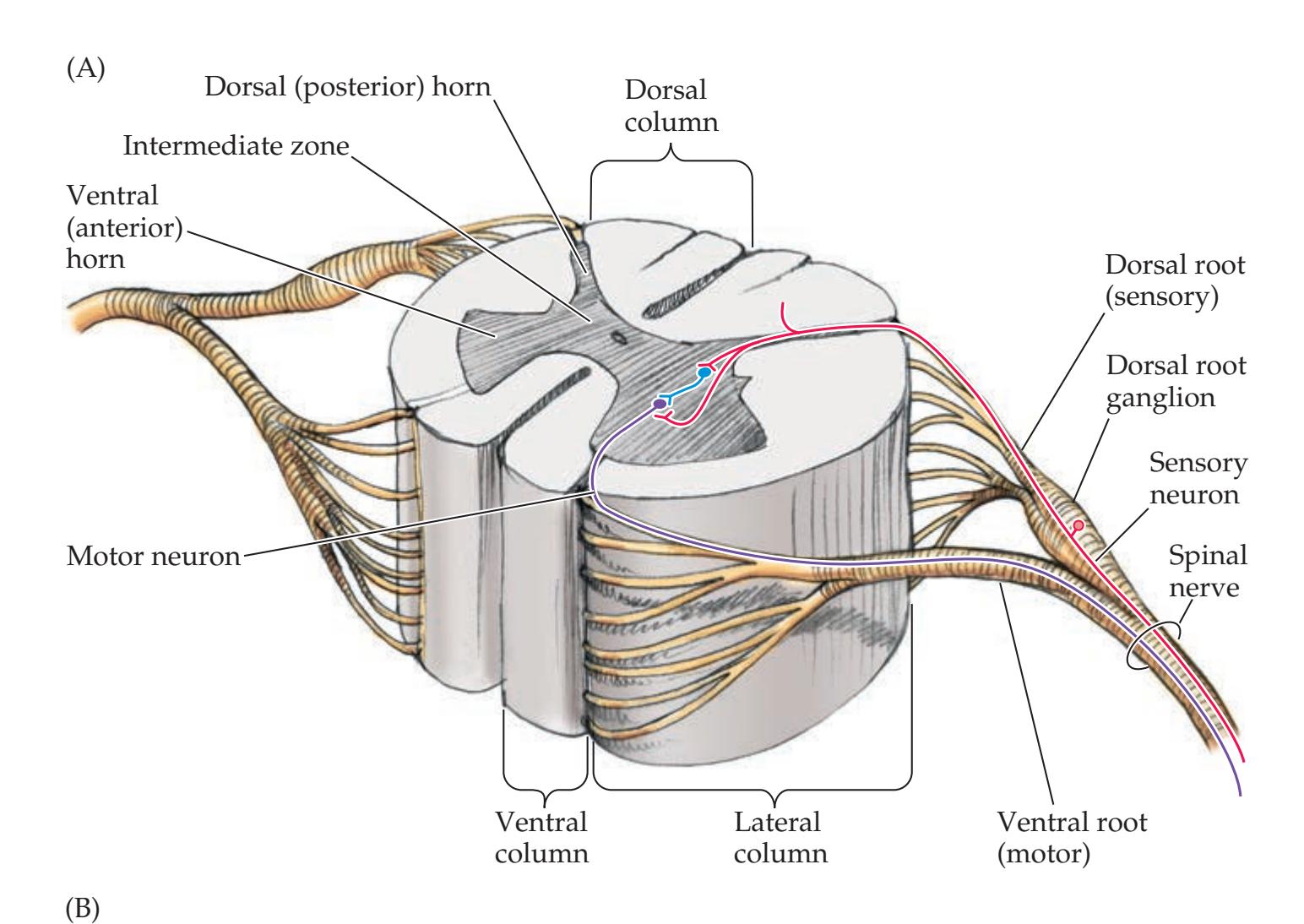

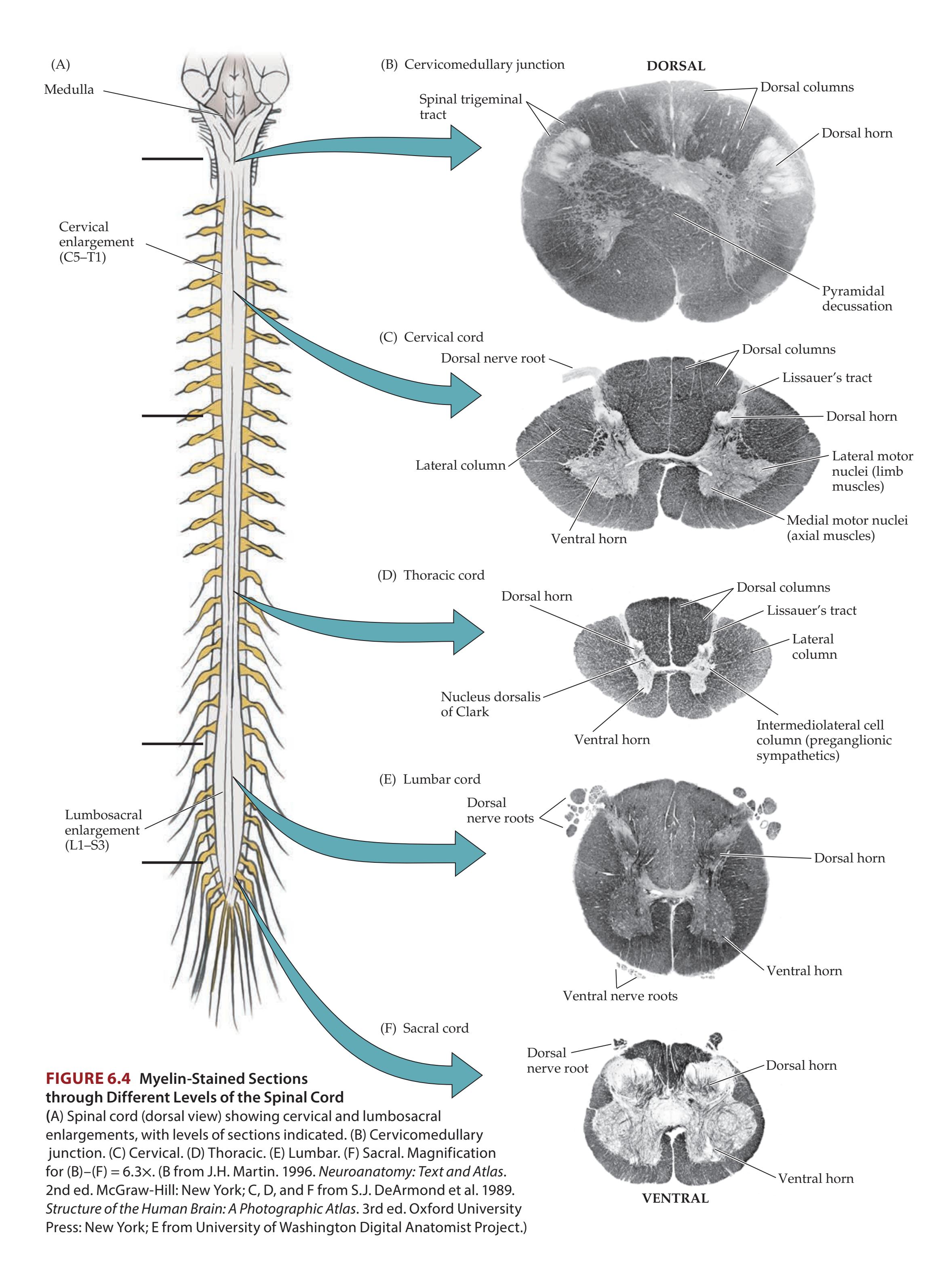

**Basic Anatomy of the Spinal Cord 224**

**Spinal Cord Blood Supply 227**

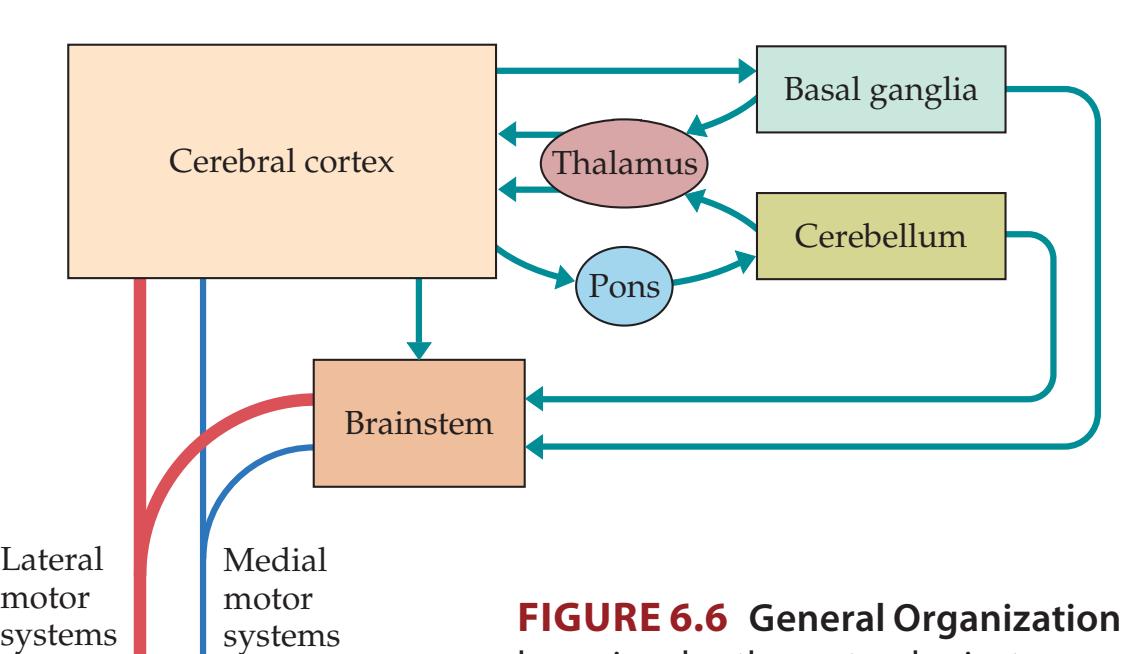

**General Organization of the Motor Systems 228**

**Lateral Corticospinal Tract 230**

**Autonomic Nervous System 236**

- **KCC 6.1** Upper Motor Neuron versus Lower Motor Neuron Lesions 239

- **KCC 6.2** Terms Used to Describe Weakness 240

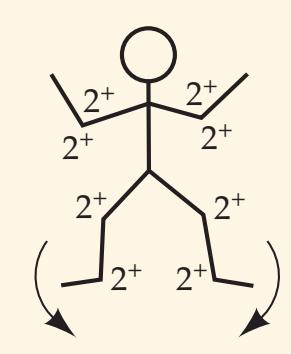

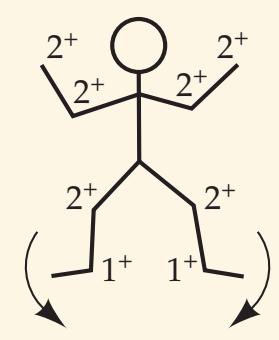

- **KCC 6.3** Weakness Patterns and Localization 240

- **KCC 6.4** Detecting Subtle Hemiparesis at the Bedside 248

- **KCC 6.5** Unsteady Gait 249

**KCC 6.6** Multiple Sclerosis 250

**KCC 6.7** Motor Neuron Disease 252

### **CLINICAL CASES 253**

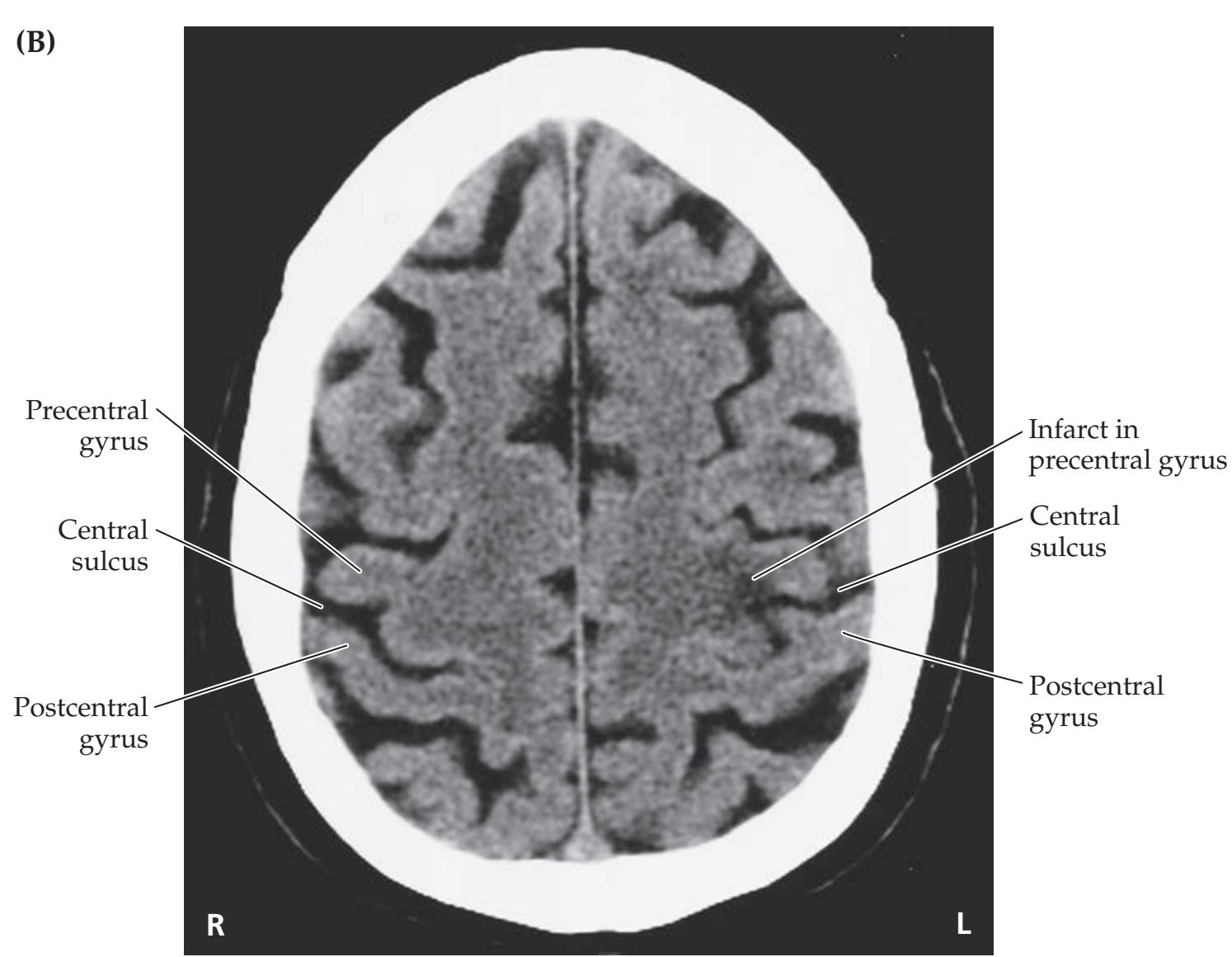

- **6.1** Sudden Onset of Right Hand Weakness 253

- **6.2** Sudden Onset of Left Foot Weakness 254

- **6.3** Sudden Onset of Right Face Weakness 255

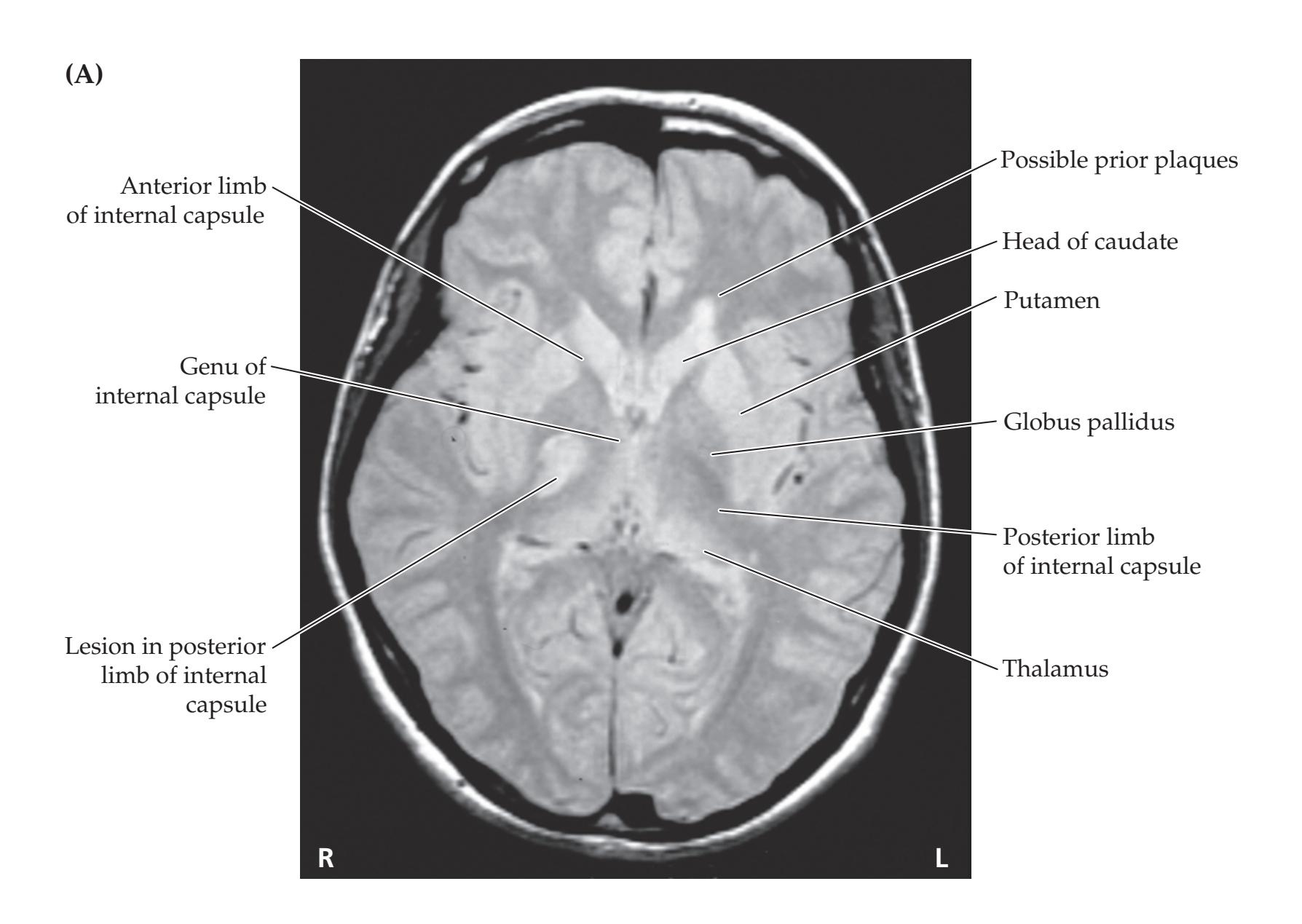

- **6.4** Pure Motor Hemiparesis I 261

- **6.5** Pure Motor Hemiparesis II 262

- **6.6** Progressive Weakness, Muscle Twitching, and Cramps 265

**Additional Cases 266**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 267**

**References 268**

## Chapter 7 *Somatosensory Pathways 273*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 274**

**Main Somatosensory Pathways 274**

**Posterior Column–Medial Lemniscal**

**Pathway 277**

**Spinothalamic Tract and Other Anterolateral Pathways 278**

**Somatosensory Cortex 280**

**Central Modulation of Pain 280**

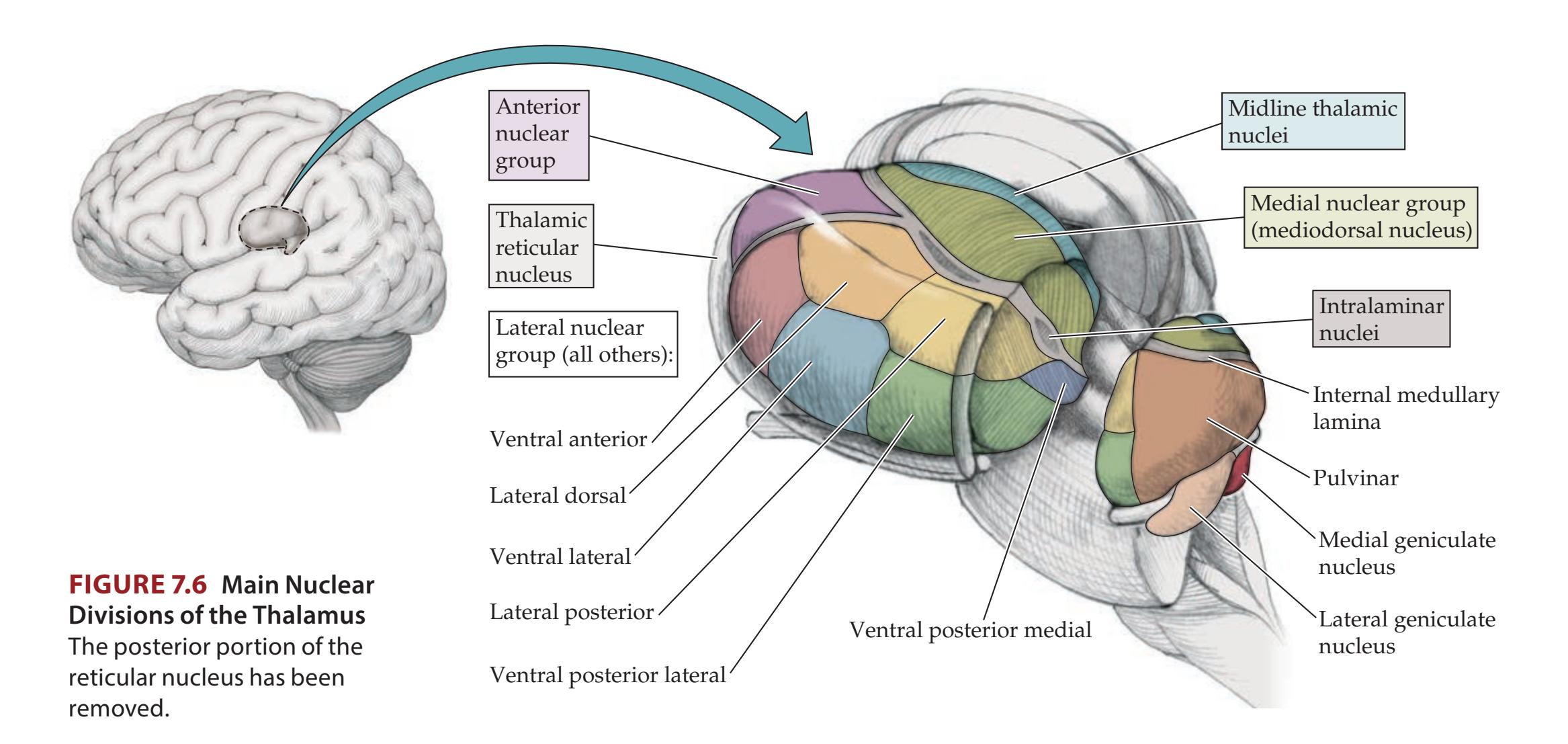

**The Thalamus 280**

**KCC 7.1** Paresthesias 286

**KCC 7.2** Spinal Cord Lesions 286

**KCC 7.3** Sensory Loss: Patterns and Localization 288

**KCC 7.4** Spinal Cord Syndromes 290

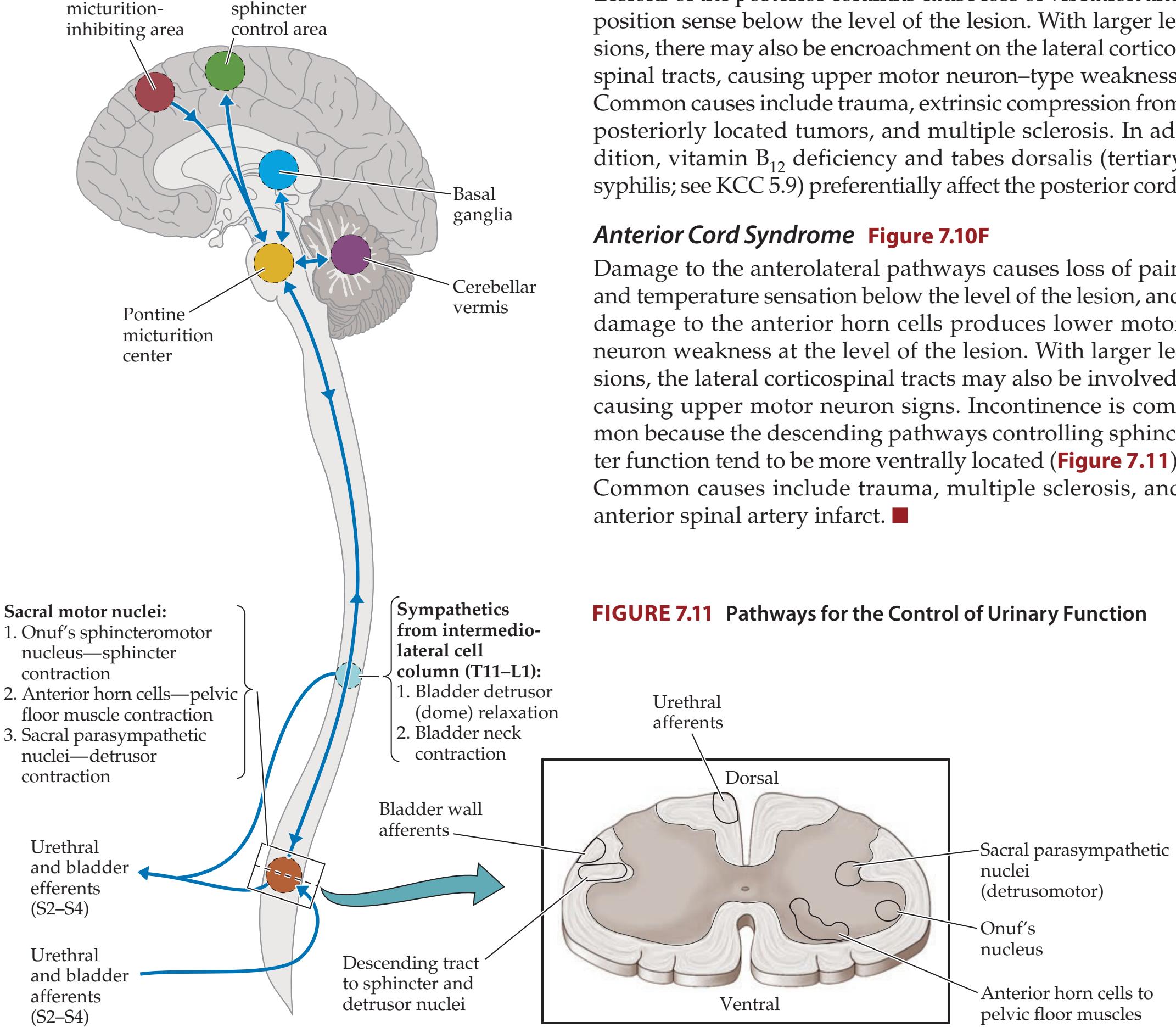

**KCC 7.5** Anatomy of Bowel, Bladder, and Sexual Function 293

### **CLINICAL CASES 296**

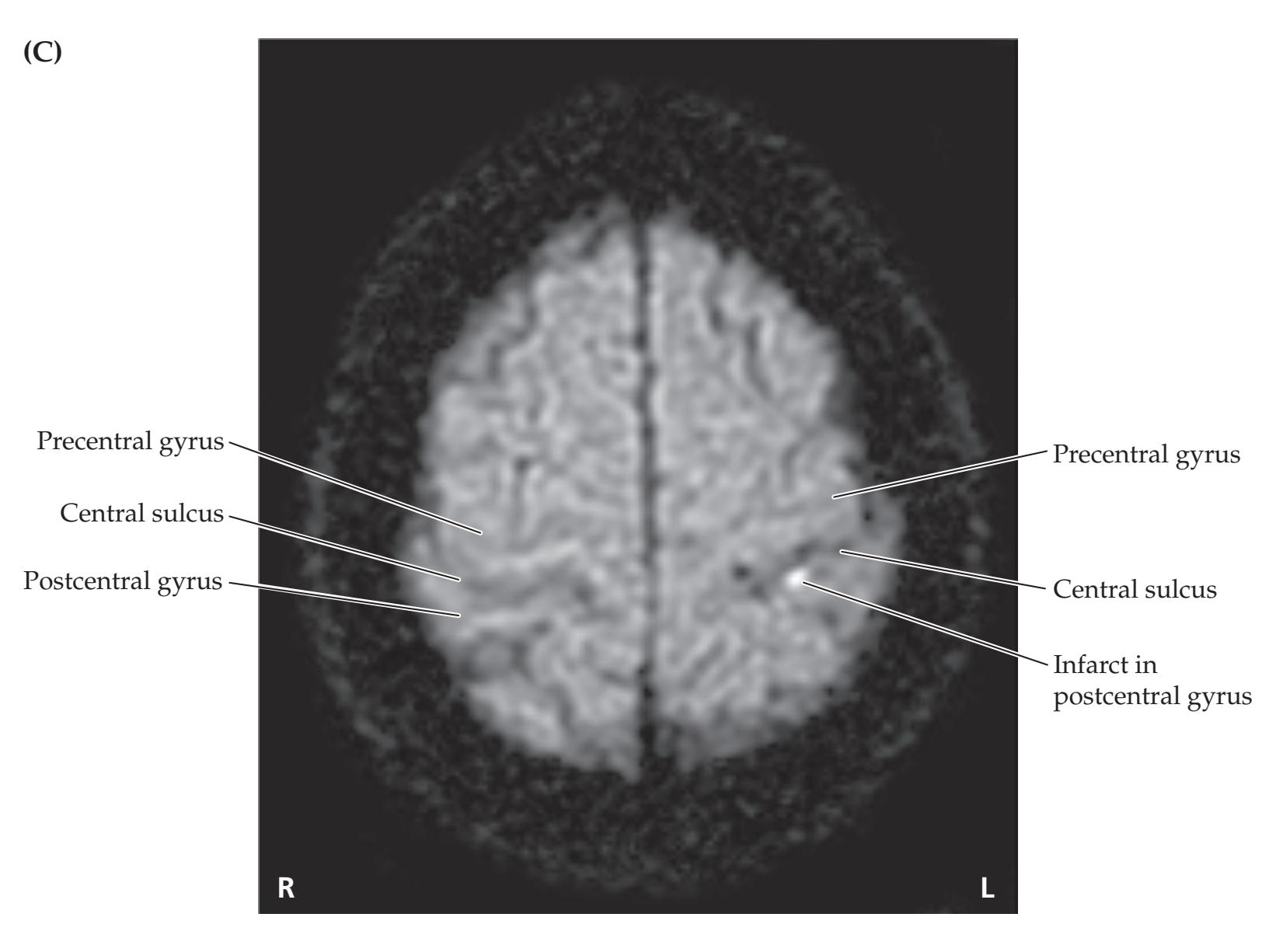

- **7.1** Sudden Onset of Right Arm Numbness 296

- **7.2** Sudden Onset of Right Face, Arm, and Leg Numbness 300

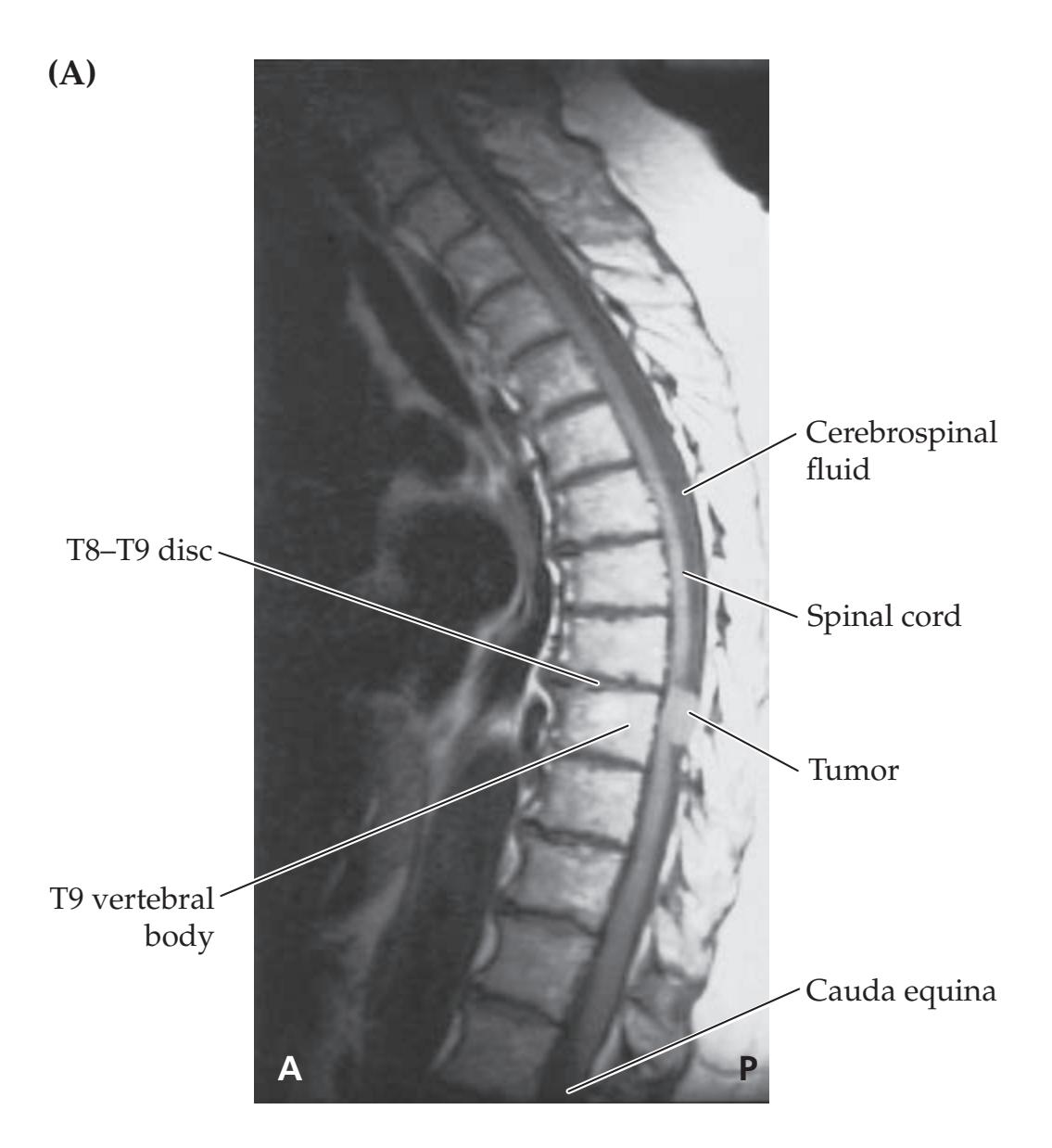

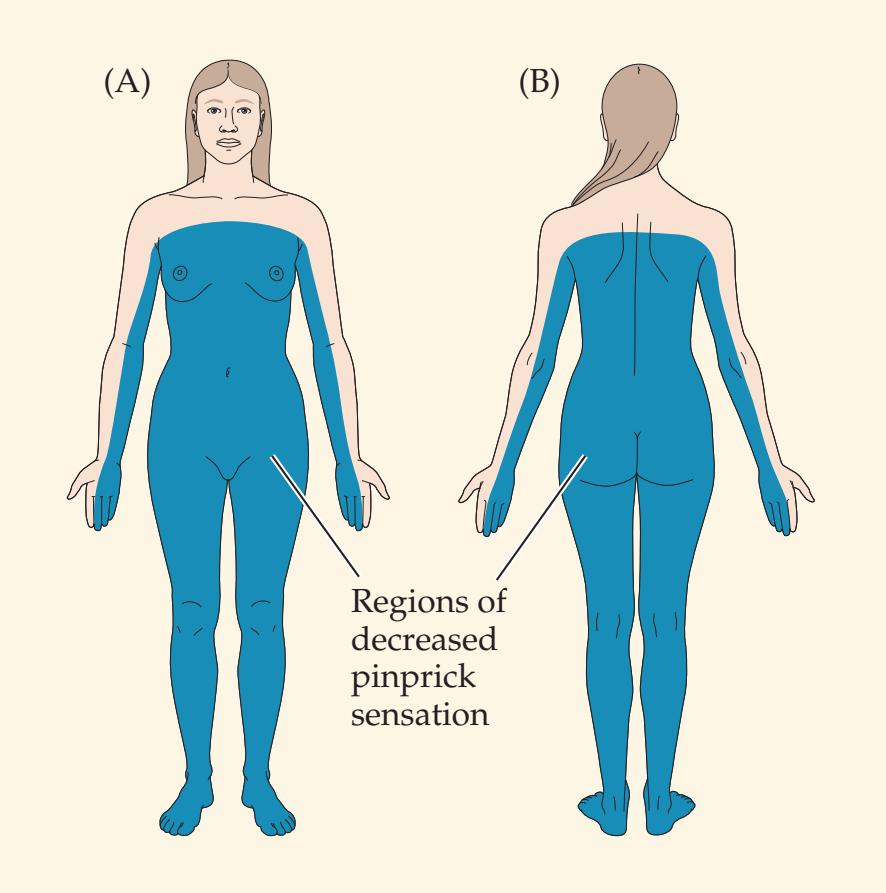

- **7.3** A Fall Causing Paraplegia and a Sensory Level 301

- **7.4** Left Leg Weakness and Right Leg Numbness 303

- **7.5** Sensory Loss over Both Shoulders 305

- **7.6** Body Tingling and Unsteady Gait 307

- **7.7** Hand Weakness, Pinprick Sensory Level, and Urinary Retention 309

**Additional Cases 311**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 311**

**References 313**

## Chapter 8 *Spinal Nerve Roots 317*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 318**

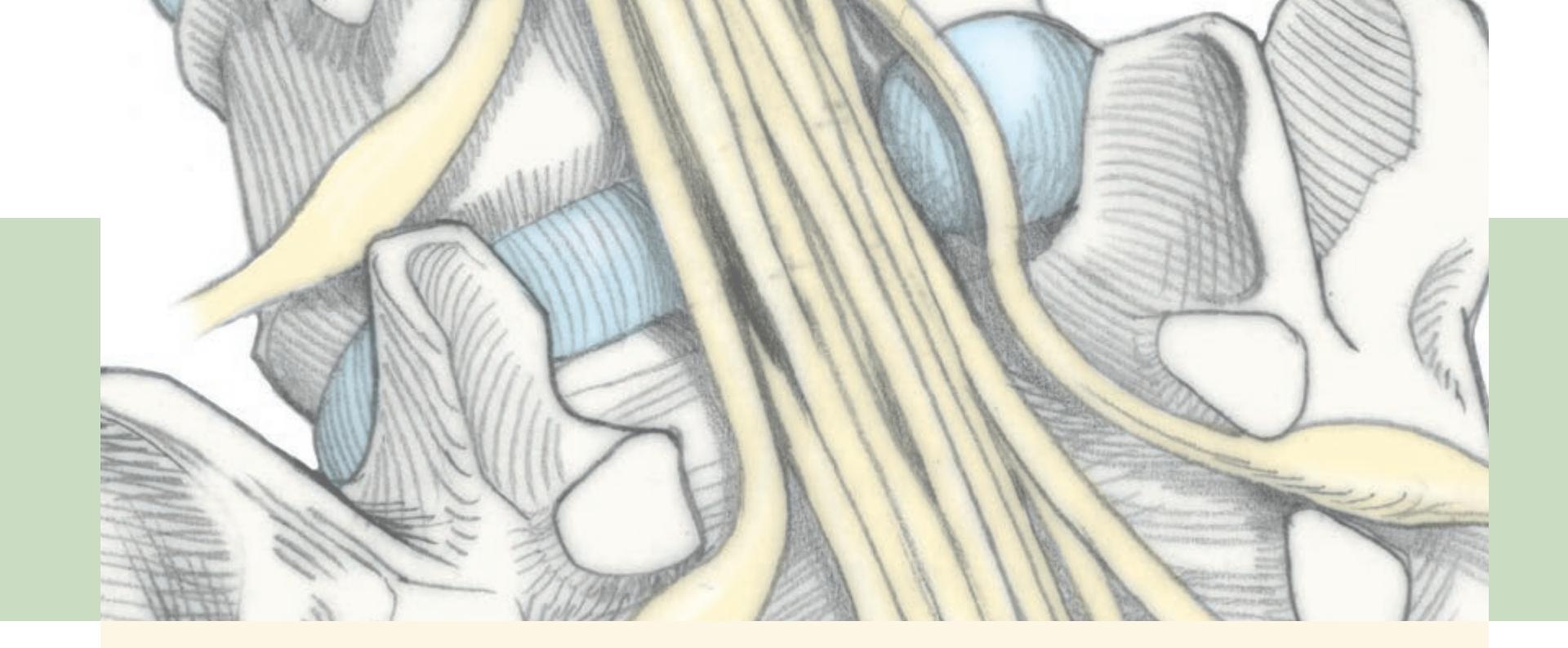

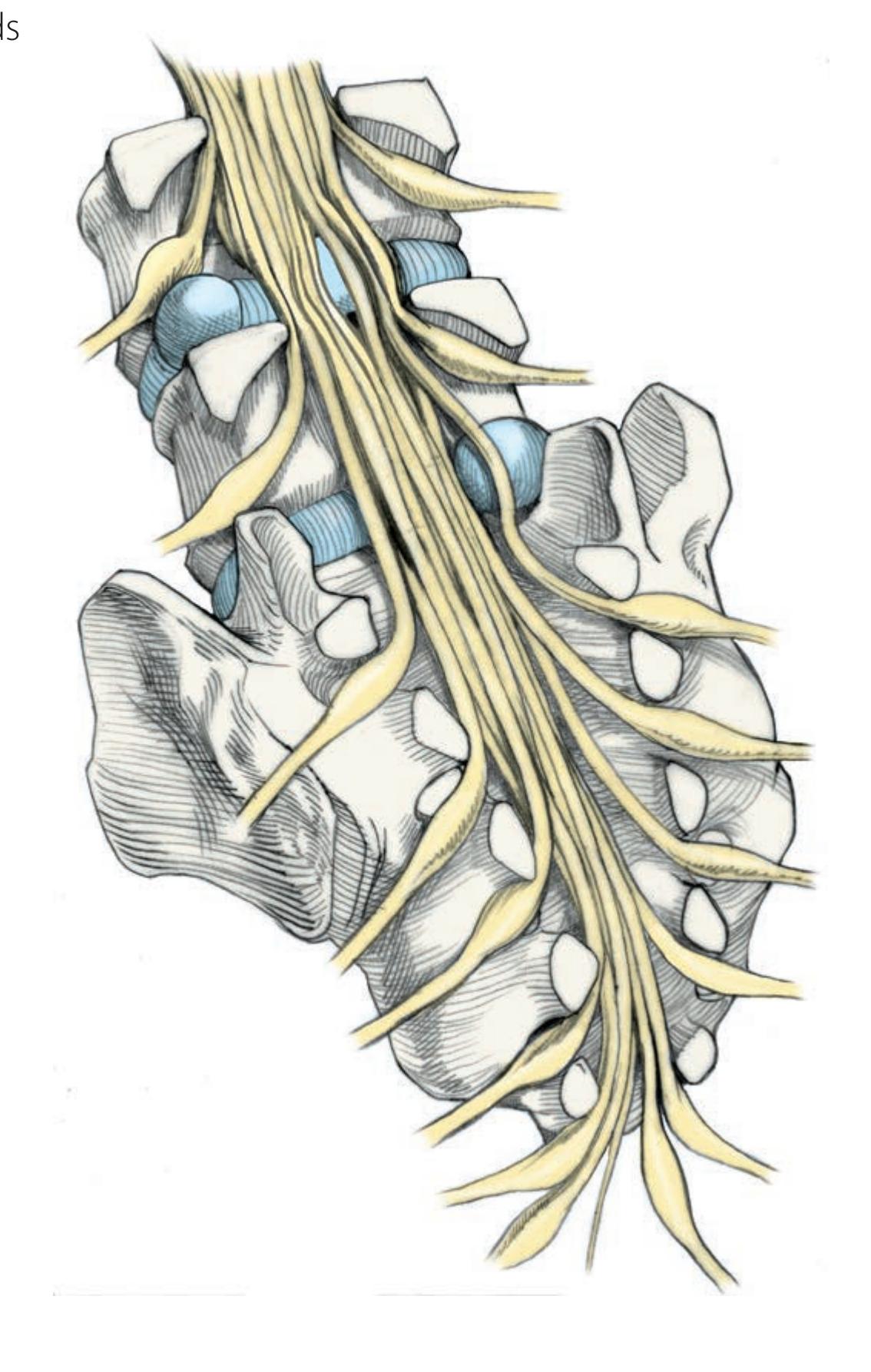

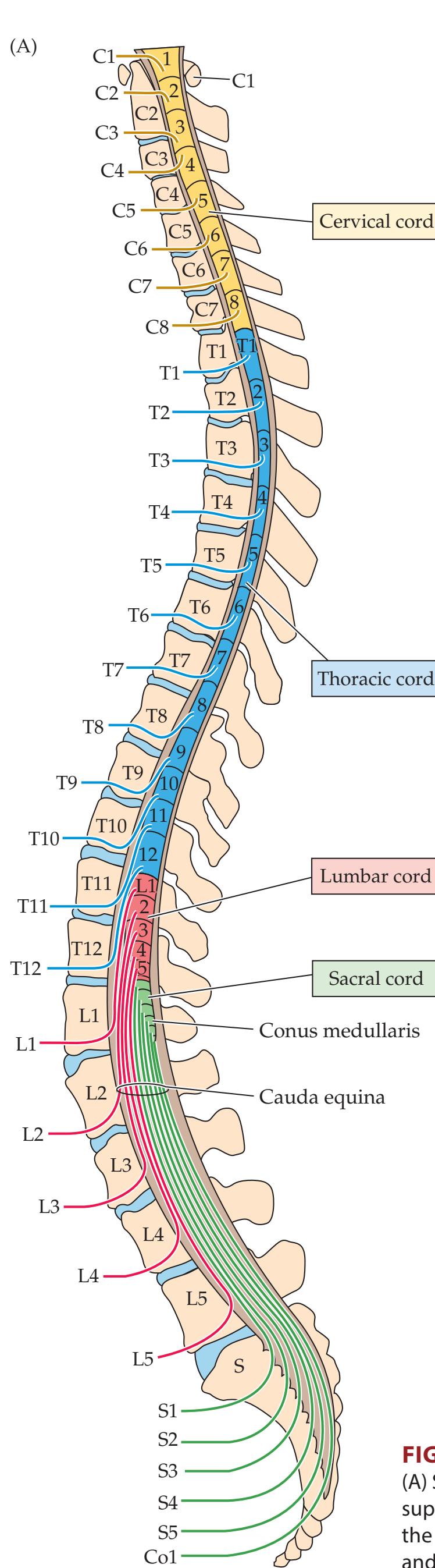

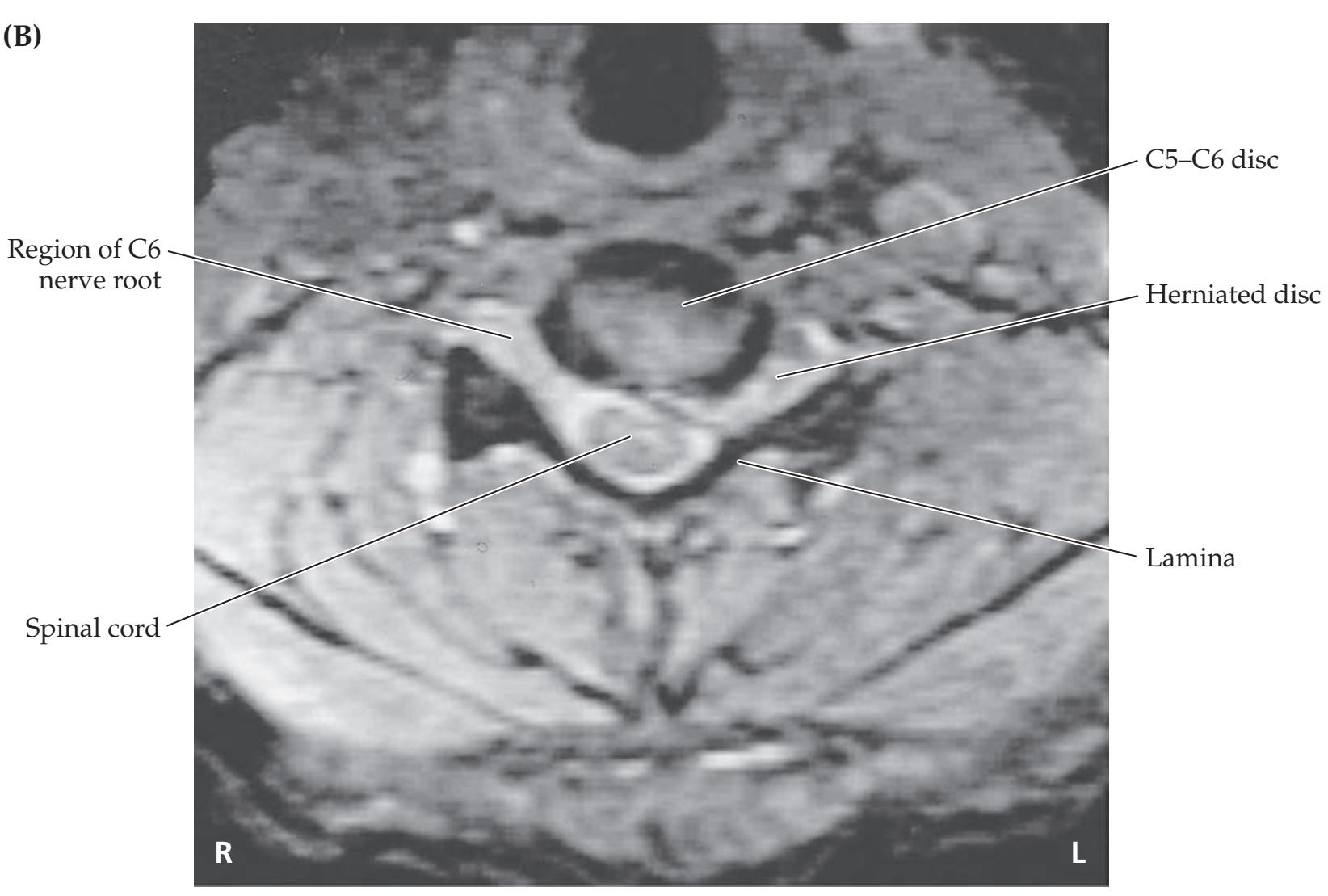

**Segmental Organization of the Nervous System 318**

**Nerve Roots in Relation to Vertebral Bones, Discs, and Ligaments 319**

**Dermatomes and Myotomes 321**

**KCC 8.1** Disorders of Nerve, Neuromuscular Junction, and Muscle 325

**KCC 8.2** Back Pain 328

**KCC 8.3** Radiculopathy 330

**Simplification: Three Nerve Roots to Remember in the Arm 332**

**Simplification: Three Nerve Roots to Remember in the Leg 332**

**KCC 8.4** Cauda Equina Syndrome 332

**KCC 8.5** Common Surgical Approaches to the Spine 333

### **CLINICAL CASES 334**

- **8.1** Unilateral Neck Pain and Tingling Numbness in the Thumb and Index Finger 334

- **8.2** Unilateral Occipital and Neck Pain 335

**x** Contents

and Hemianopia 432

**KCC 10.6** Dissection of the Carotid or Vertebral Arteries 409

Contents **xi**

| 10.9

Left Face and Arm Weakness

435 | Additional Cases

453 |

|---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 10.10

Left Hemineglect

436 | BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE

453 |

| 10.11

Left Hemineglect, Hemiplegia, and Hemianopia

438 | References

454 |

| 10.12

Unilateral Proximal Arm and Leg Weakness

444 | |

| 10.13

Right Frontal Headache and Left Arm Numbness in a

Woman with Gastric Carcinoma

449 | |

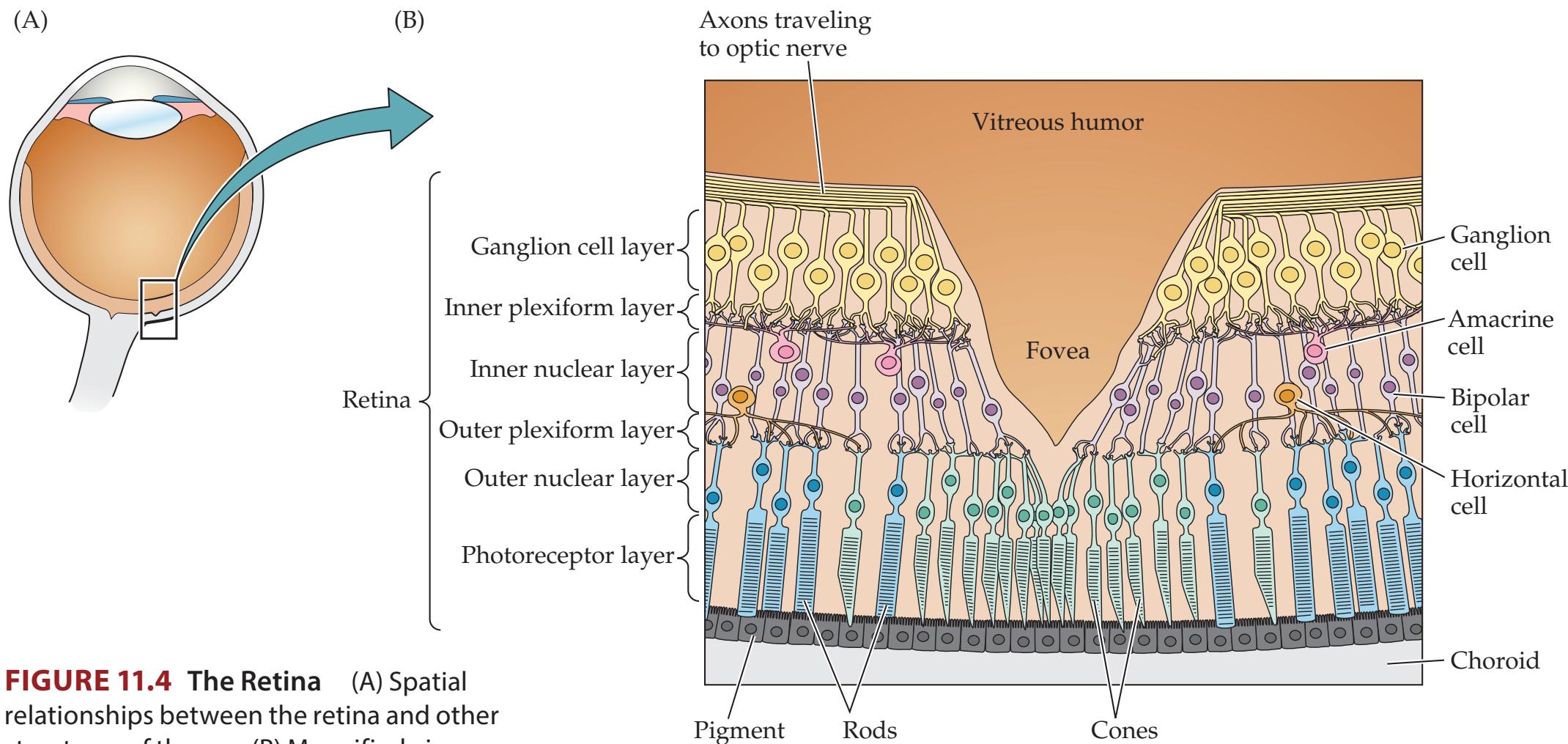

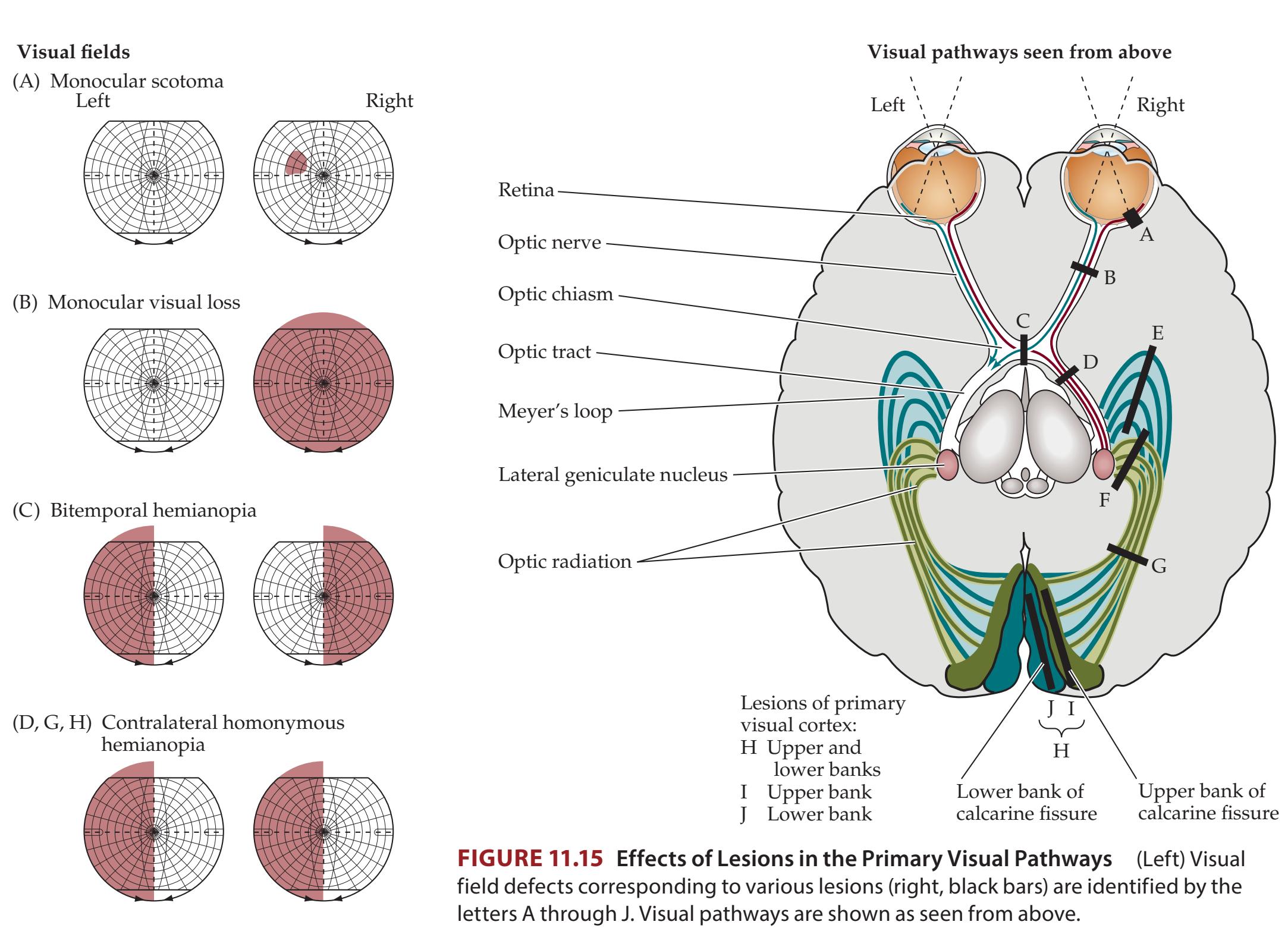

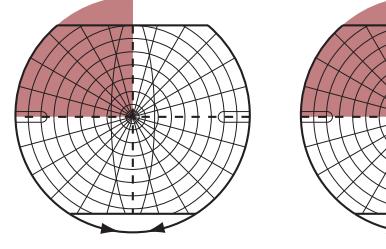

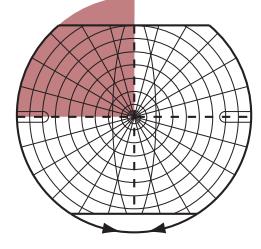

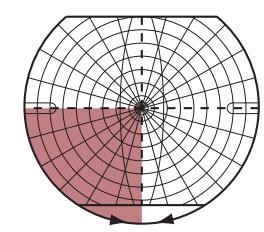

| Chapter 11

Visual System

459 | |

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW

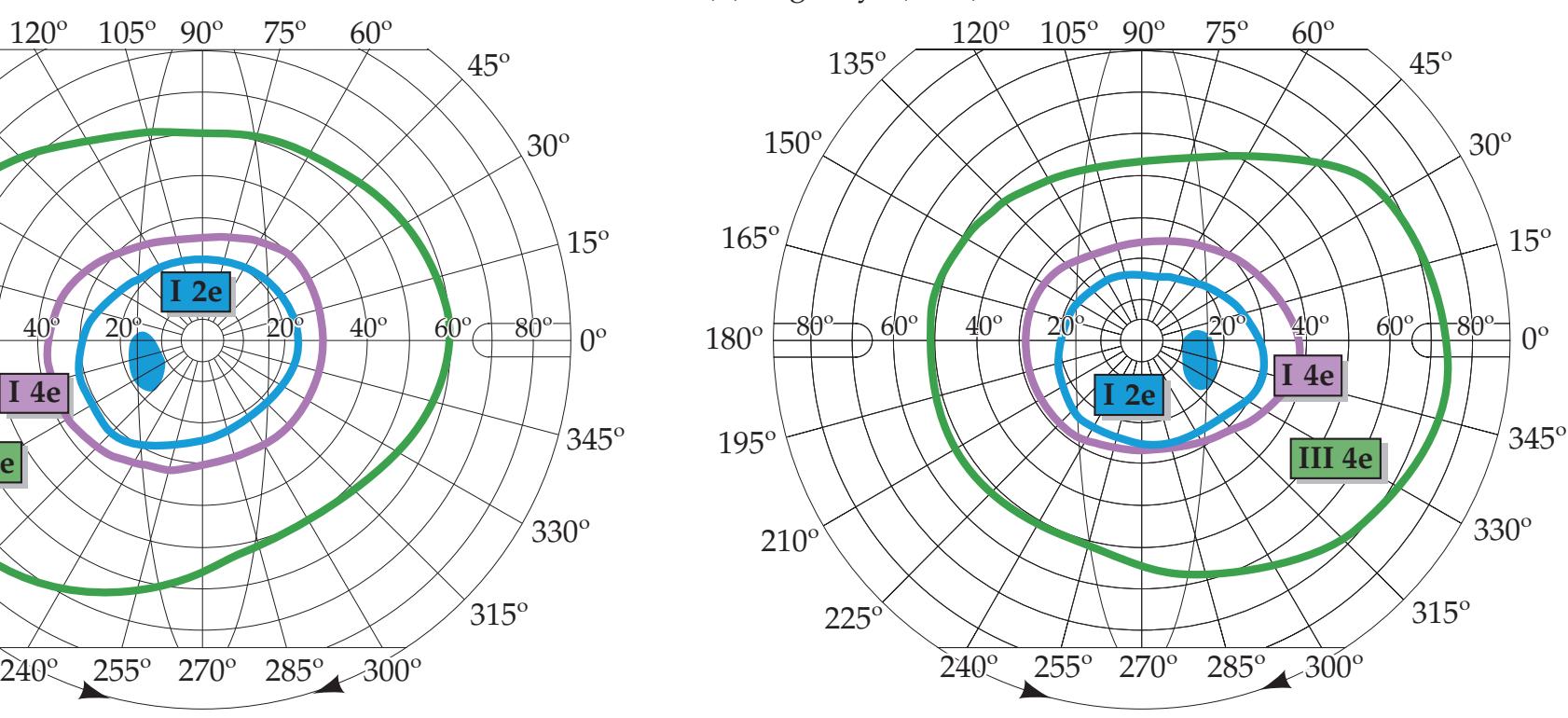

460 | CLINICAL CASES

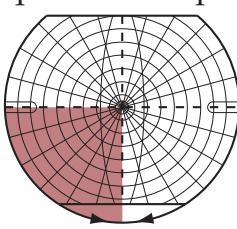

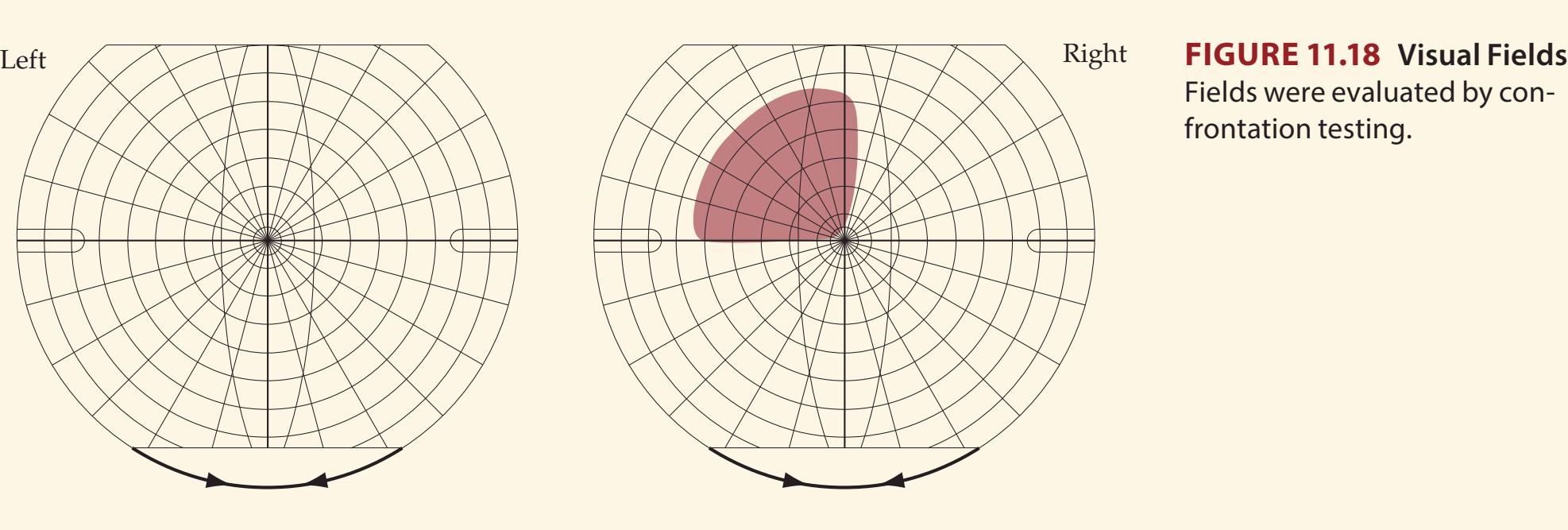

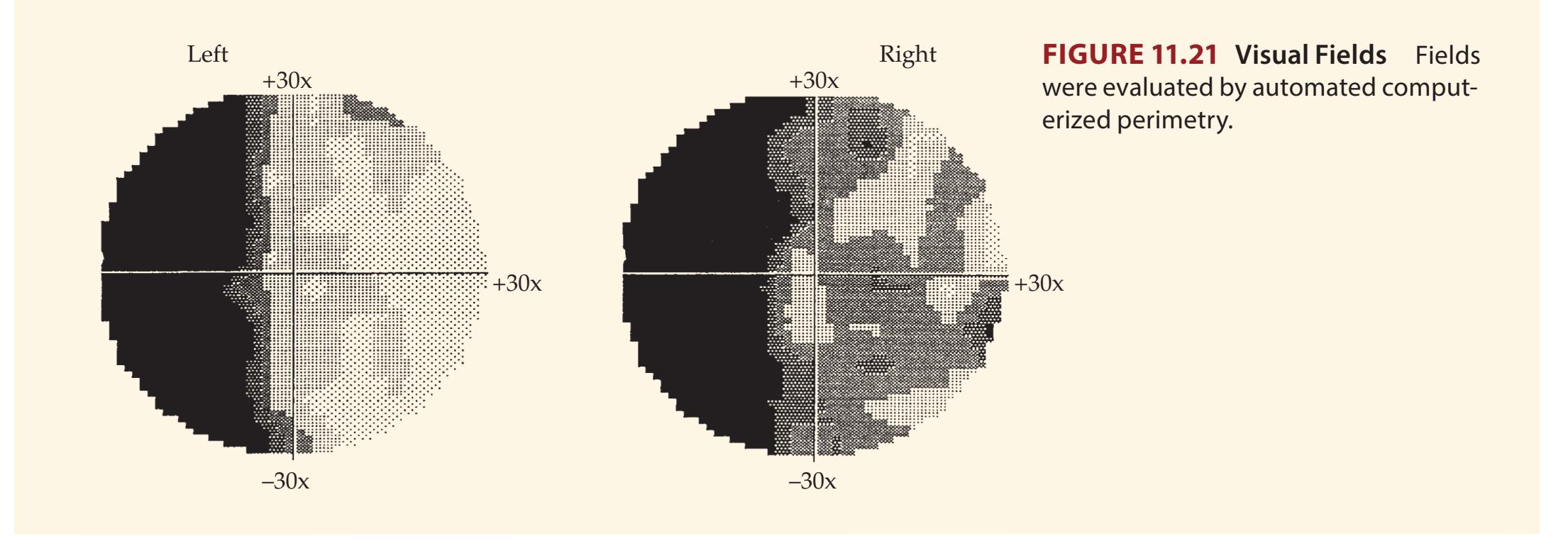

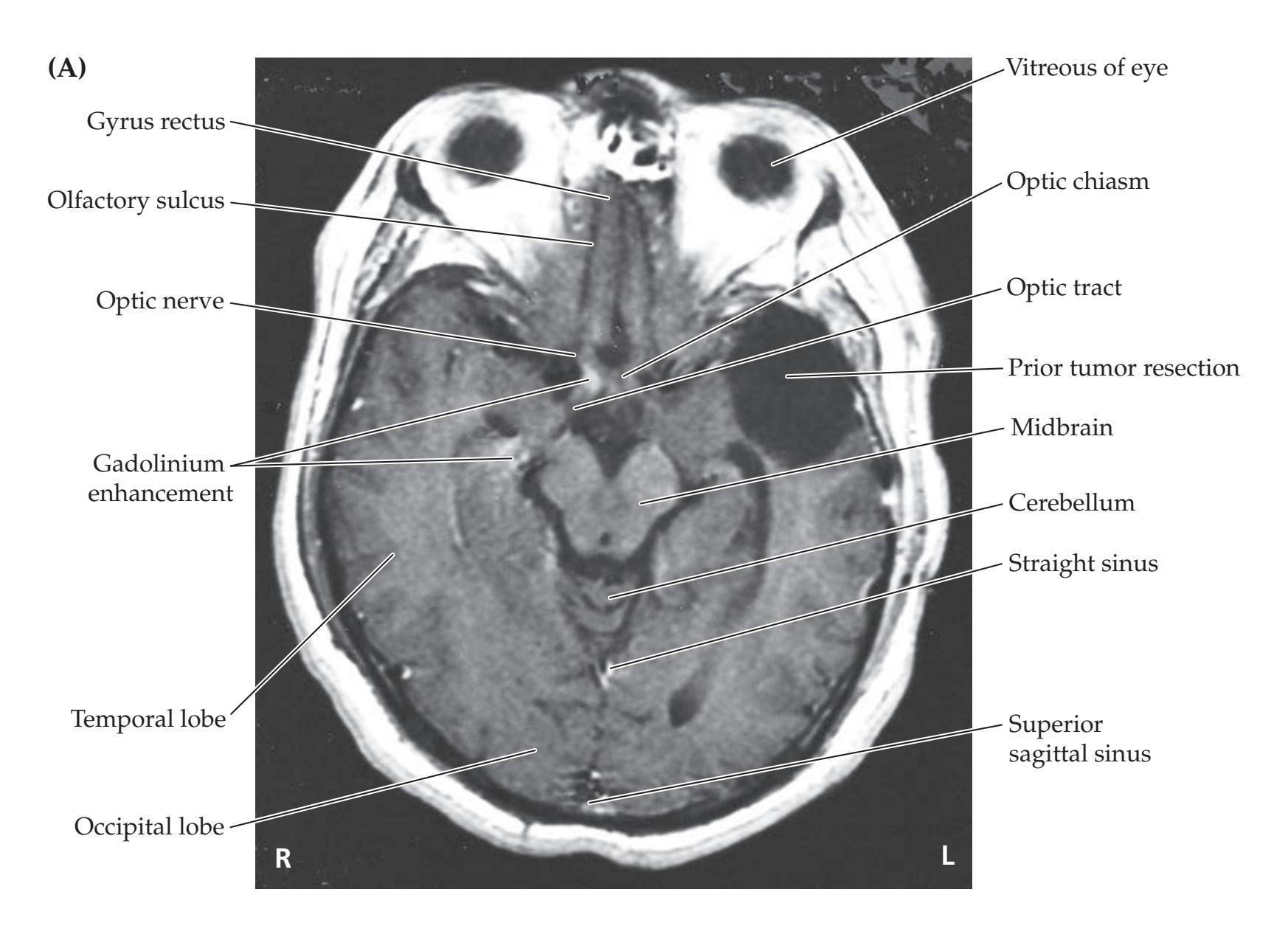

478 |

| Eyes and Retina

460 | 11.1

A Dark Spot Seen with One Eye

478 |

| Optic Nerves, Optic Chiasm, and

Optic Tracts

463 | 11.2

Vision Loss in One Eye

479 |

| Lateral Geniculate Nucleus and Extrageniculate

Pathways

464 | 11.3

Menstrual Irregularity and Bitemporal Hemianopia

481 |

| Optic Radiations to Primary Visual Cortex

465 | 11.4

Hemianopia after Treatment for a Temporal

Lobe Tumor

483 |

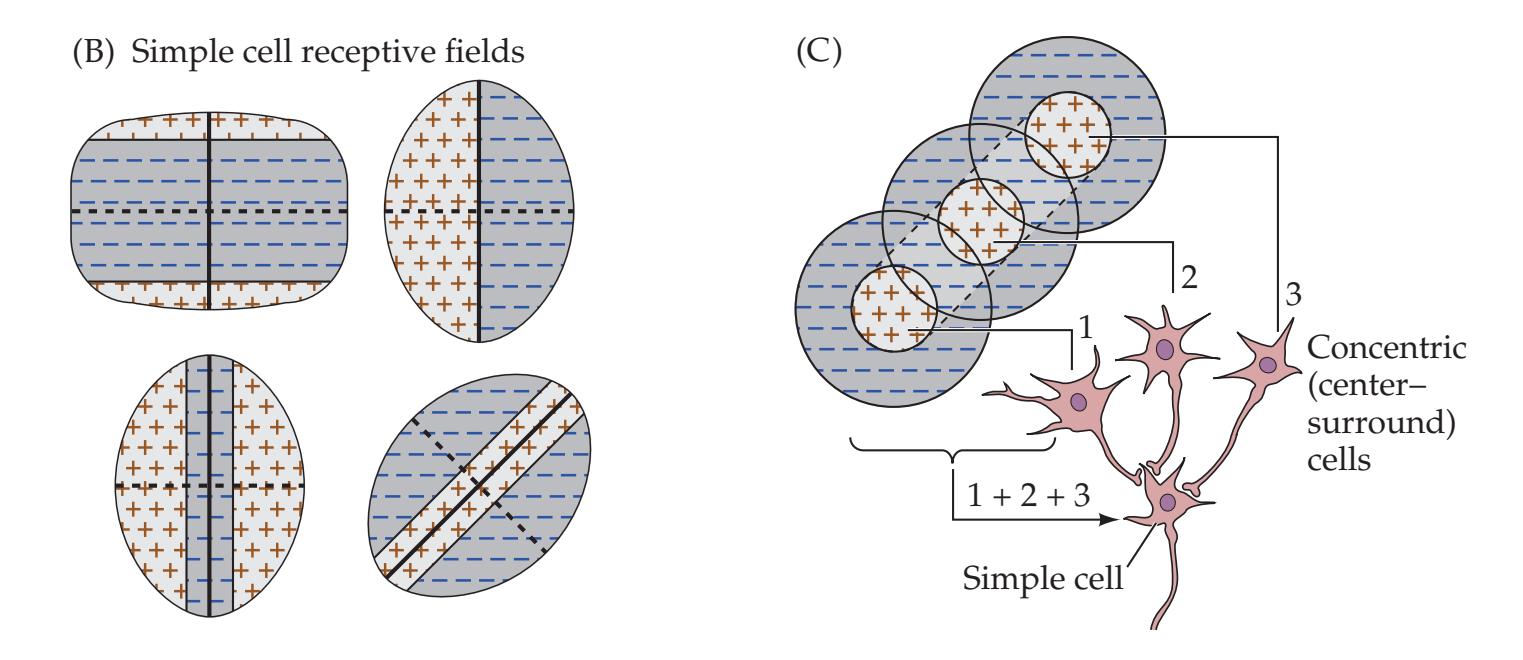

| Visual Processing in the Neocortex

466 | 11.5

Visual Changes Caused by Migraine Headaches?

485 |

| KCC 11.1

Assessment of Visual Disturbances

470 | 11.6

Sudden Loss of Left Vision

486 |

| KCC 11.2

Localization of Visual Field Defects

472 | 11.7

Visual Field Match-Up

489 |

| KCC 11.3

Blood Supply and Ischemia in

the Visual Pathways

476 | Additional Cases

490 |

| KCC 11.4

Optic Neuritis

477 | BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE

492 |

| Chapter 12

Brainstem I: Surface Anatomy and Cranial Nerves

495 | References

493 |

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW

496 | CN X: Vagus Nerve

534 |

| Surface Features of the Brainstem

497 | CN XI: Spinal Accessory Nerve

536 |

| Skull Foramina and Cranial Nerve

Exit Points

500 | CN XII: Hypoglossal Nerve

537 |

| Sensory and Motor Organization of

the Cranial Nerves

502 | KCC 12.7

Disorders of CN IX, X, XI, and XII

537 |

| Functions and Course of the Cranial Nerves

505 | KCC 12.8

Hoarseness, Dysarthria, Dysphagia, and

Pseudobulbar Affect

538 |

| CN I: Olfactory Nerve

507 | Review: Cranial Nerve Combinations

539 |

| KCC 12.1

Anosmia (CN I)

508 | CLINICAL CASES

541 |

| CN II: Optic Nerve

508 | 12.1

Anosmia and Visual Impairment

541 |

| CN III, IV, and VI: Oculomotor, Trochlear, and

Abducens Nerves

508 | 12.2

Cheek Numbness and a Bulging Eye

543 |

| CN V: Trigeminal Nerve

510 | 12.3

Jaw Numbness and Episodes of Loss of

Consciousness

544 |

| KCC 12.2

Trigeminal Nerve Disorders (CN V)

514 | 12.4

Isolated Facial Weakness

545 |

| CN VII: Facial Nerve

515 | 12.5

Hearing Loss and Dizziness

550 |

| KCC 12.3

Facial Nerve Lesions (CN VII)

518 | 12.6

Hoarse Voice Following Cervical Disc Surgery

551 |

| KCC 12.4

Corneal Reflex and Jaw Jerk Reflex (CN V, VII)

520 | 12.7

Hoarseness, with Unilateral Wasting of the Neck and

Tongue Muscles

555 |

| CN VIII: Vestibulocochlear Nerve

520 | 12.8

Uncontrollable Laughter, Dysarthria, Dysphagia, and

Left-Sided Weakness

557 |

| KCC 12.5

Hearing Loss (CN VIII)

527 | Additional Cases

561 |

| KCC 12.6

Dizziness and Vertigo (CN VIII)

529 | BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE

561 |

| CN IX: Glossopharyngeal Nerve

532 | References

563 |

**xii** Contents

## Chapter 13 *Brainstem II: Eye Movements and Pupillary Control 567*

| ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW | 568 |

|--------------------------------|-----|

|--------------------------------|-----|

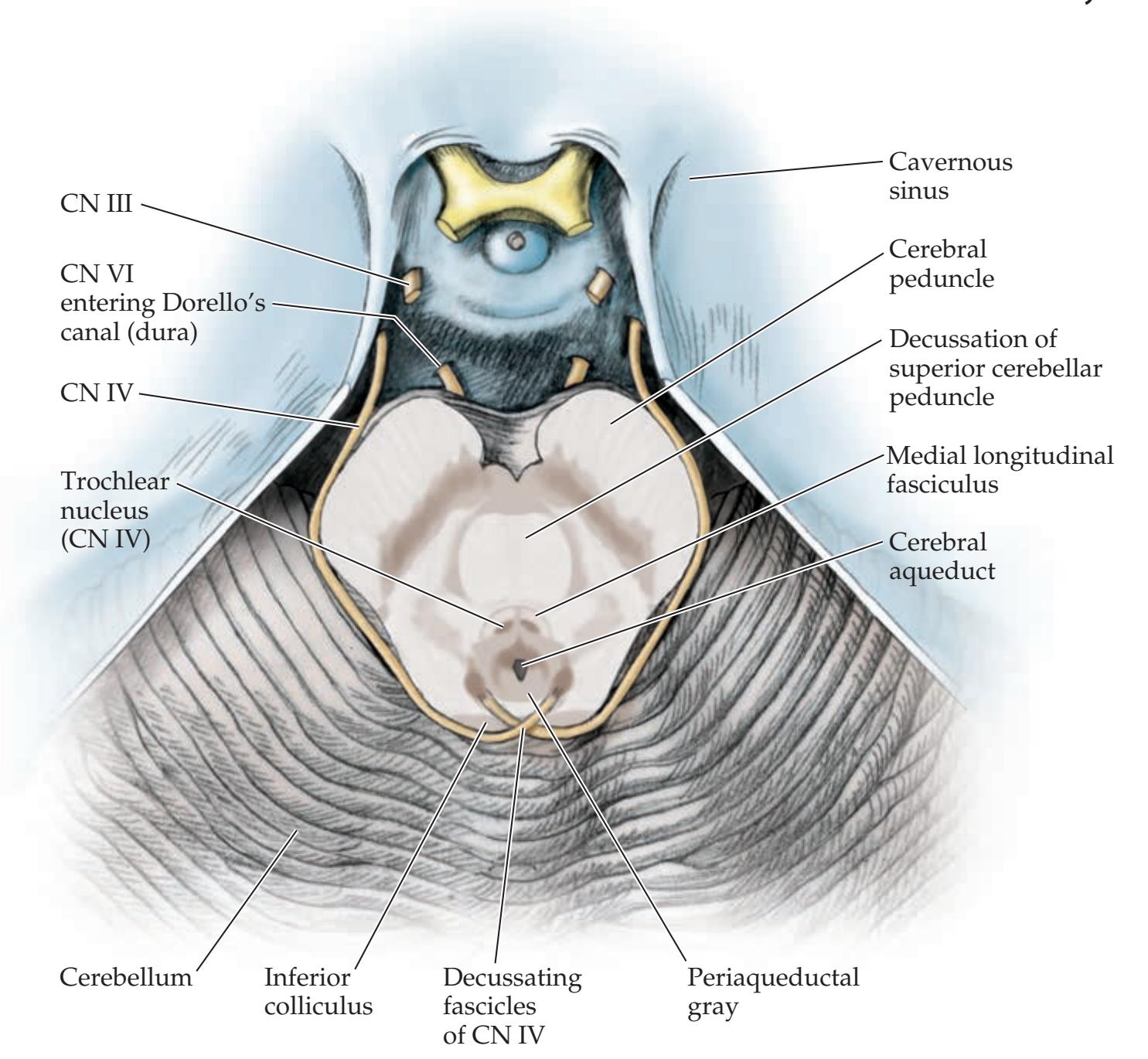

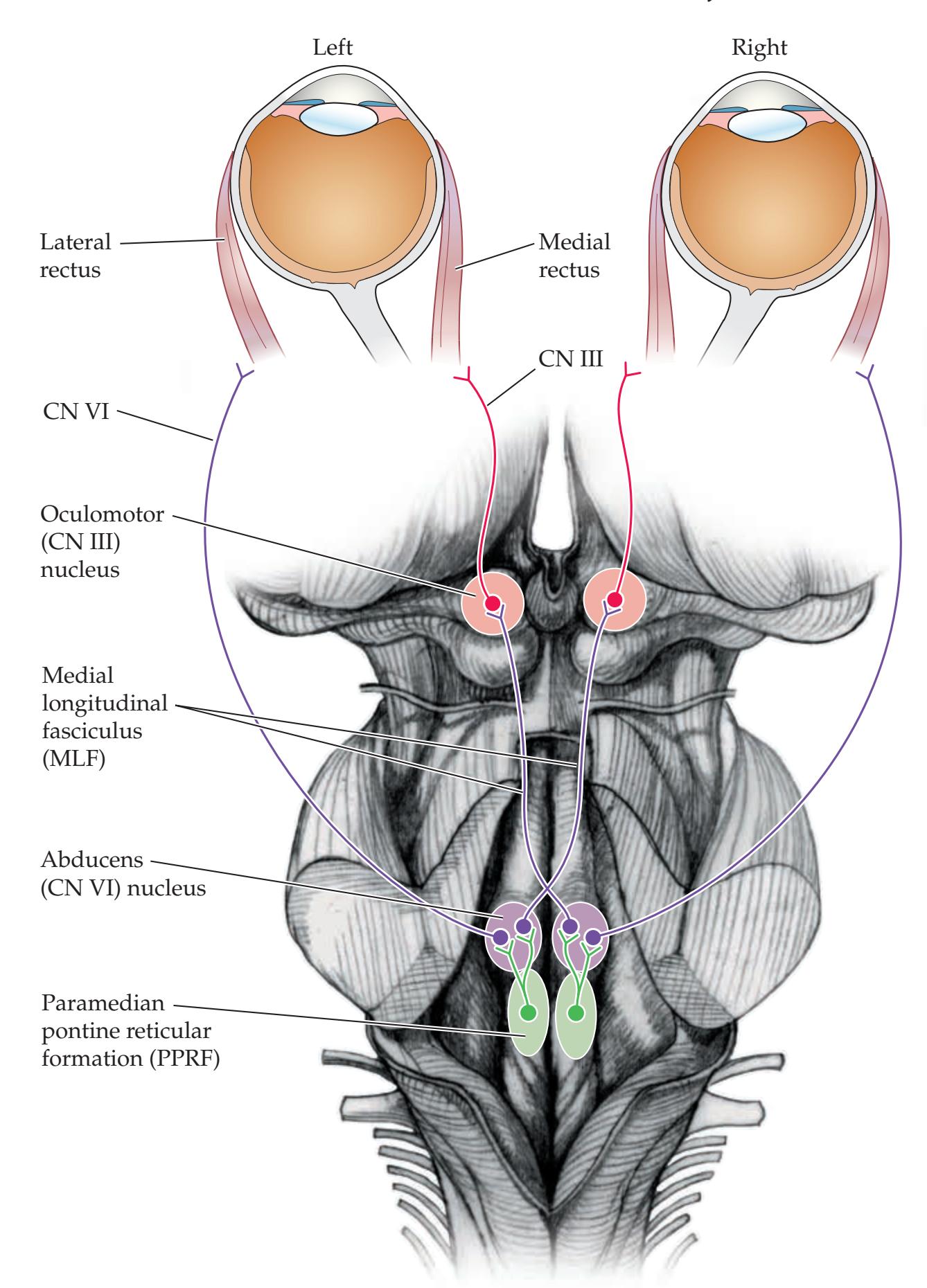

**Extraocular Muscles, Nerves, and Nuclei 568**

**KCC 13.1** Diplopia 573

**KCC 13.2** Oculomotor Palsy (CN III) 574

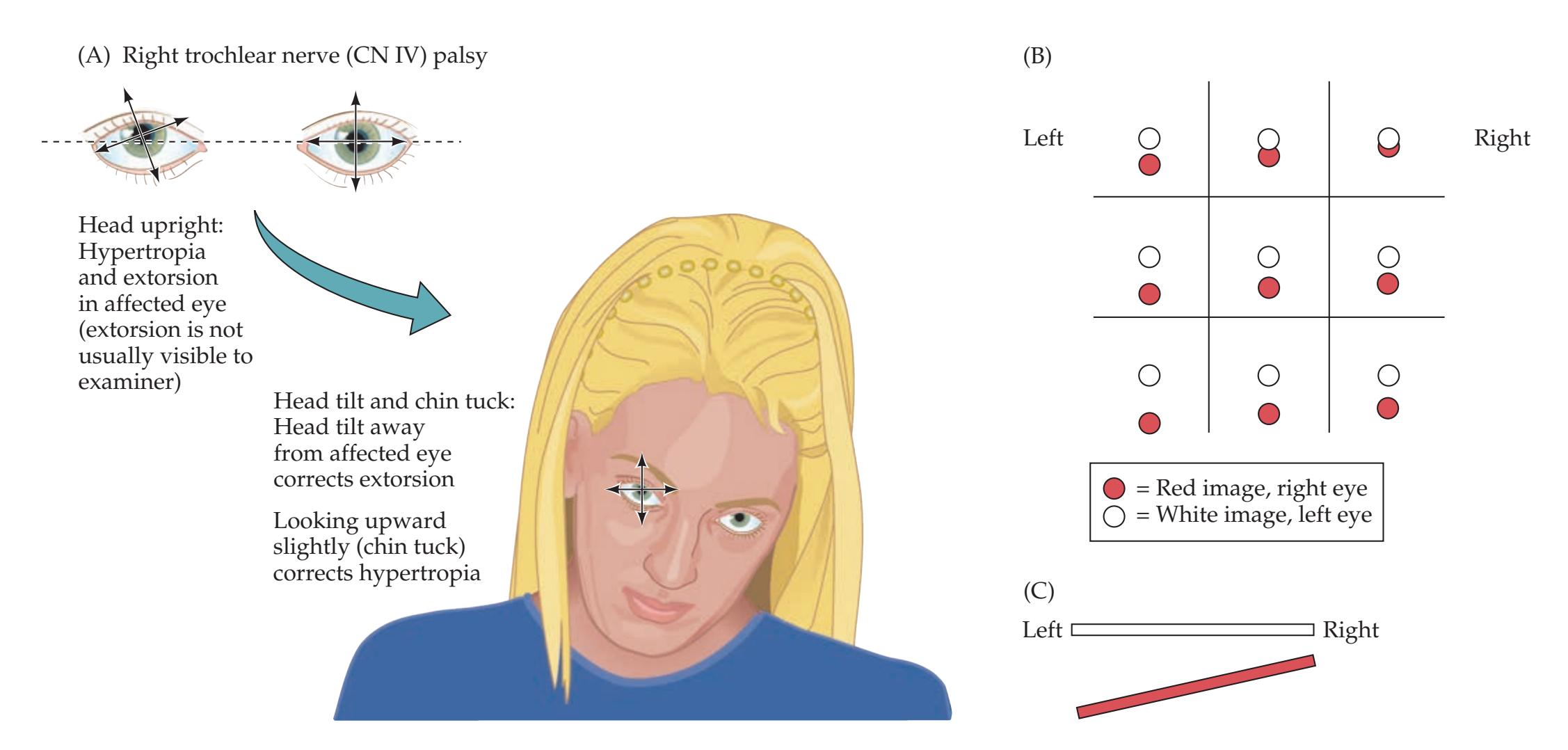

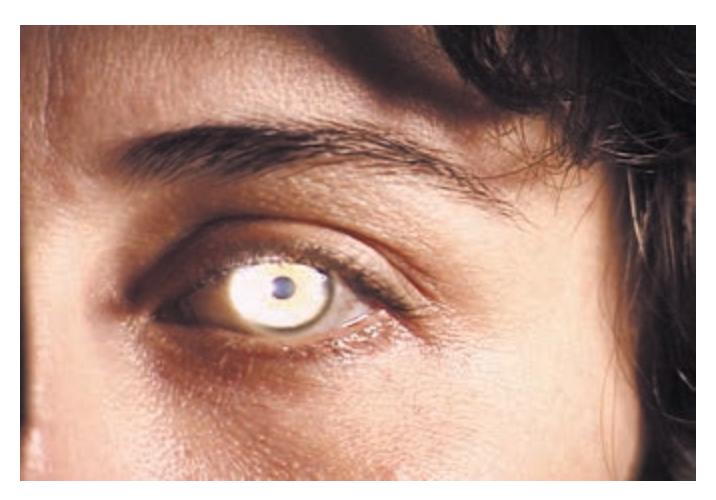

**KCC 13.3** Trochlear Palsy (CN IV) 576

**KCC 13.4** Abducens Palsy (CN VI) 577

### **The Pupils and Other Ocular Autonomic Pathways 578**

**KCC 13.5** Pupillary Abnormalities 581

**KCC 13.6** Ptosis 584

### **Cavernous Sinus and Orbital Apex 585**

**KCC 13.7** Cavernous Sinus Syndrome (CN III, IV, VI, V1) and Orbital Apex Syndrome (CN II, III, IV, VI, V1) 586

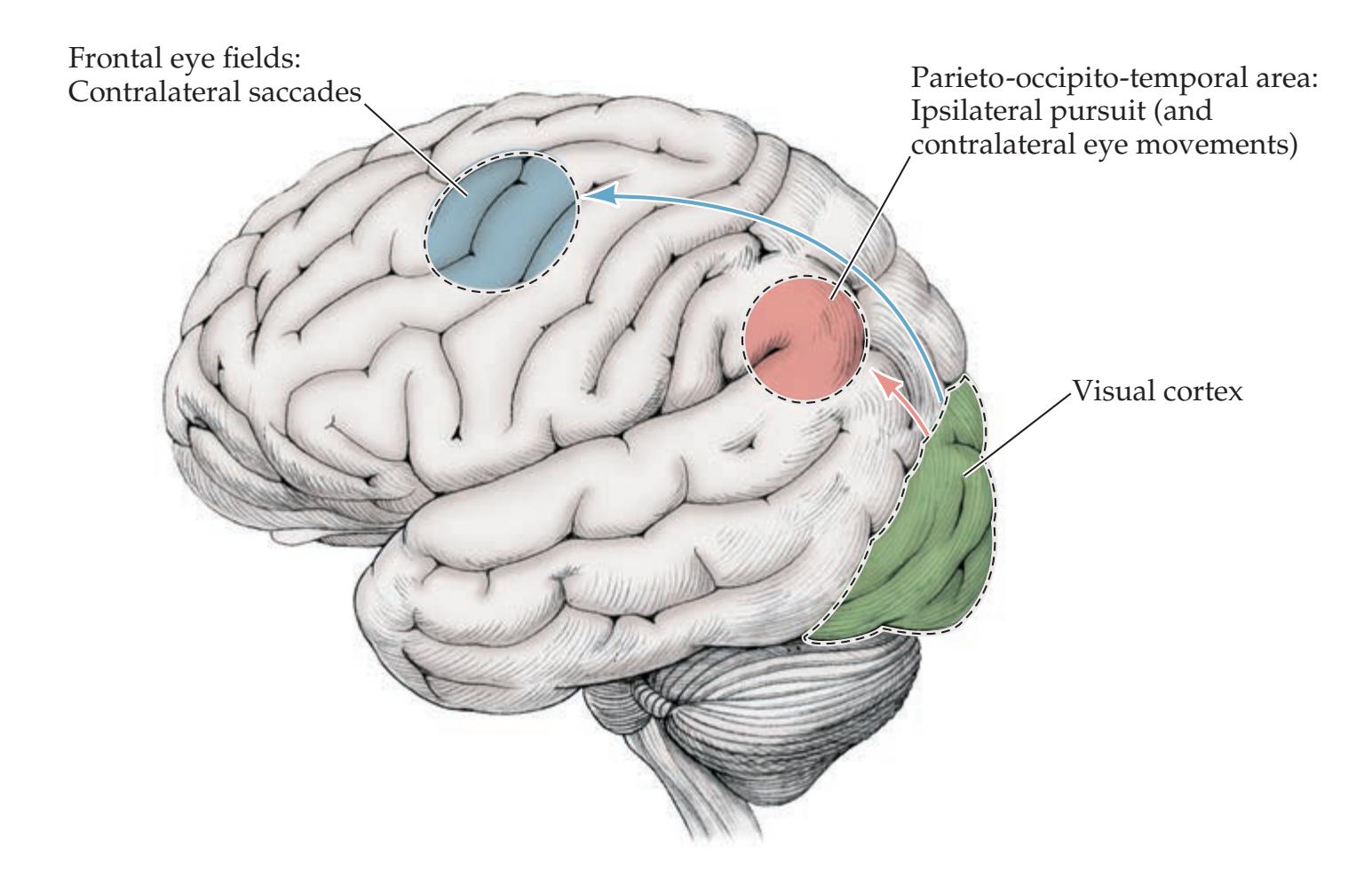

### **Supranuclear Control of Eye Movements 586**

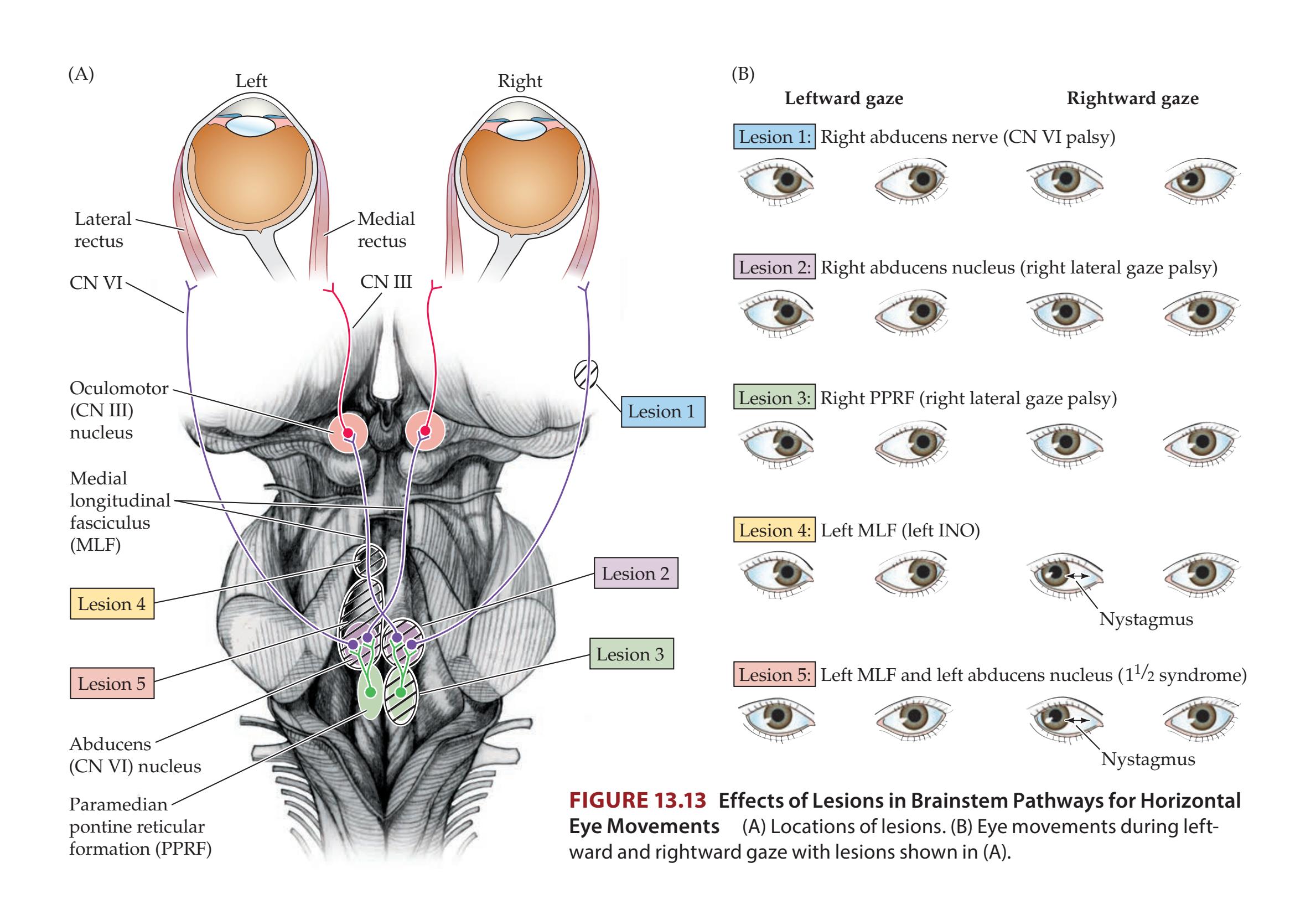

**KCC 13.8** Brainstem Lesions Affecting Horizontal Gaze 588

**KCC 13.9** Parinaud's Syndrome 590

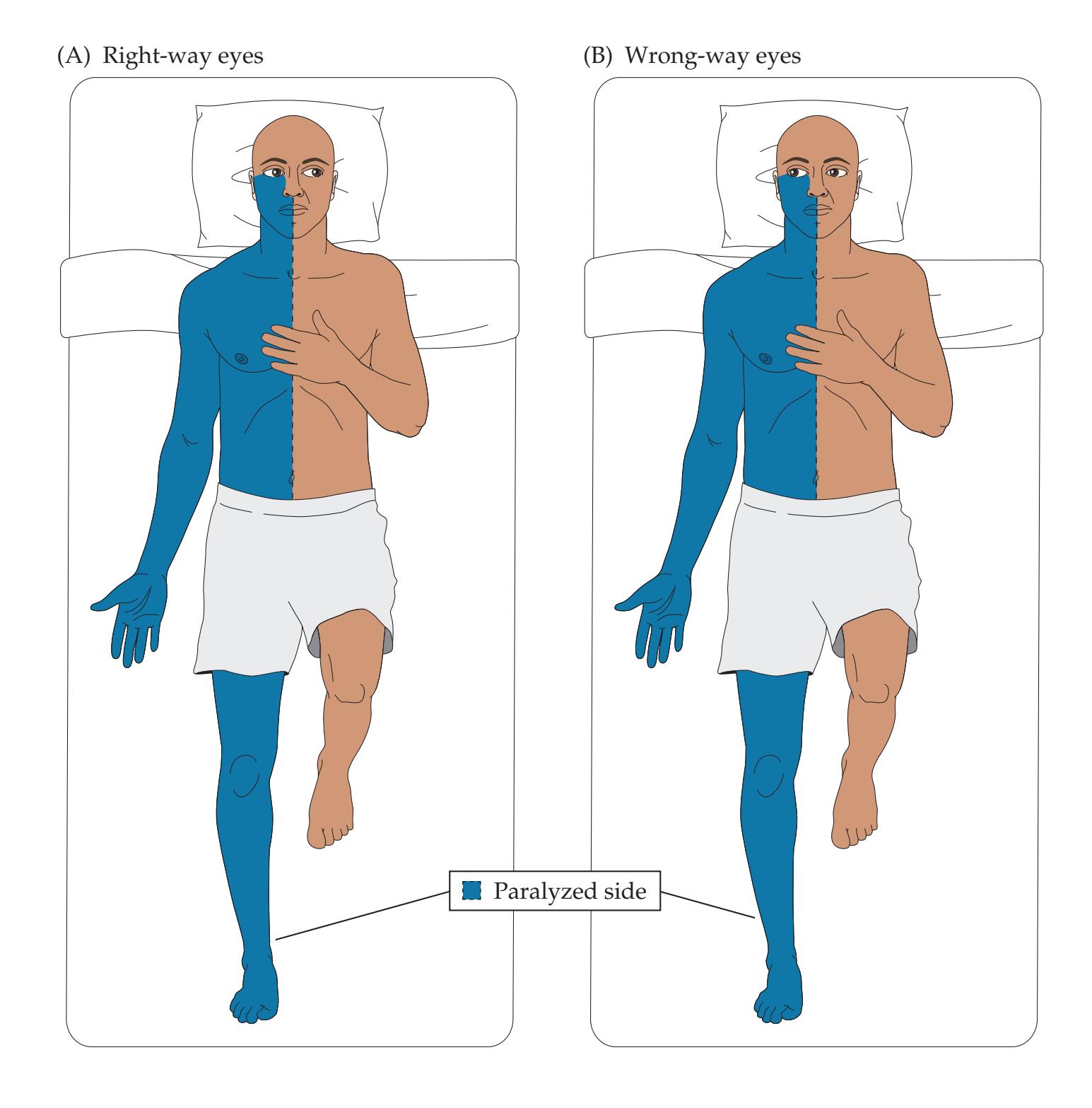

**KCC 13.10** Right-Way Eyes and Wrong-Way Eyes 591

### **CLINICAL CASES 593**

**13.1** Double Vision and Unilateral Eye Pain 593

**13.2** A Diabetic with Horizontal Diplopia 595

**13.3** Vertical Diplopia 596

**13.4** Left Eye Pain and Horizontal Diplopia 597

**13.5** Unilateral Headache, Ophthalmoplegia, and Forehead Numbness 598

**13.6** Ptosis, Miosis, and Anhidrosis 600

**13.7** Wrong-Way Eyes 604

**13.8** Horizontal Diplopia in a Patient with Multiple Sclerosis 605

**13.9** Headaches and Impaired Upgaze 606

**Additional Cases 607**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 609**

**References 612**

## Chapter 14 *Brainstem III: Internal Structures and Vascular Supply 615*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 616**

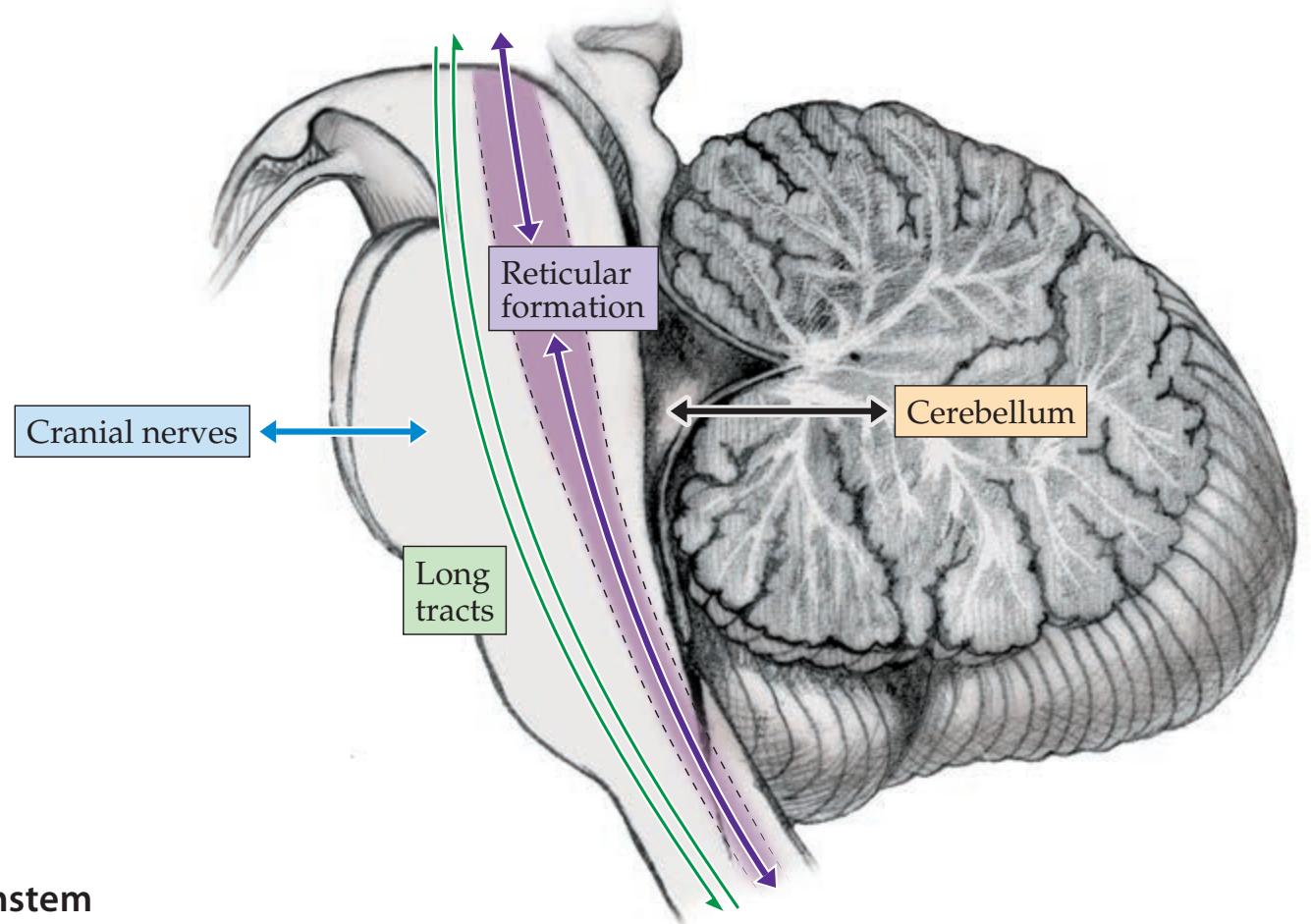

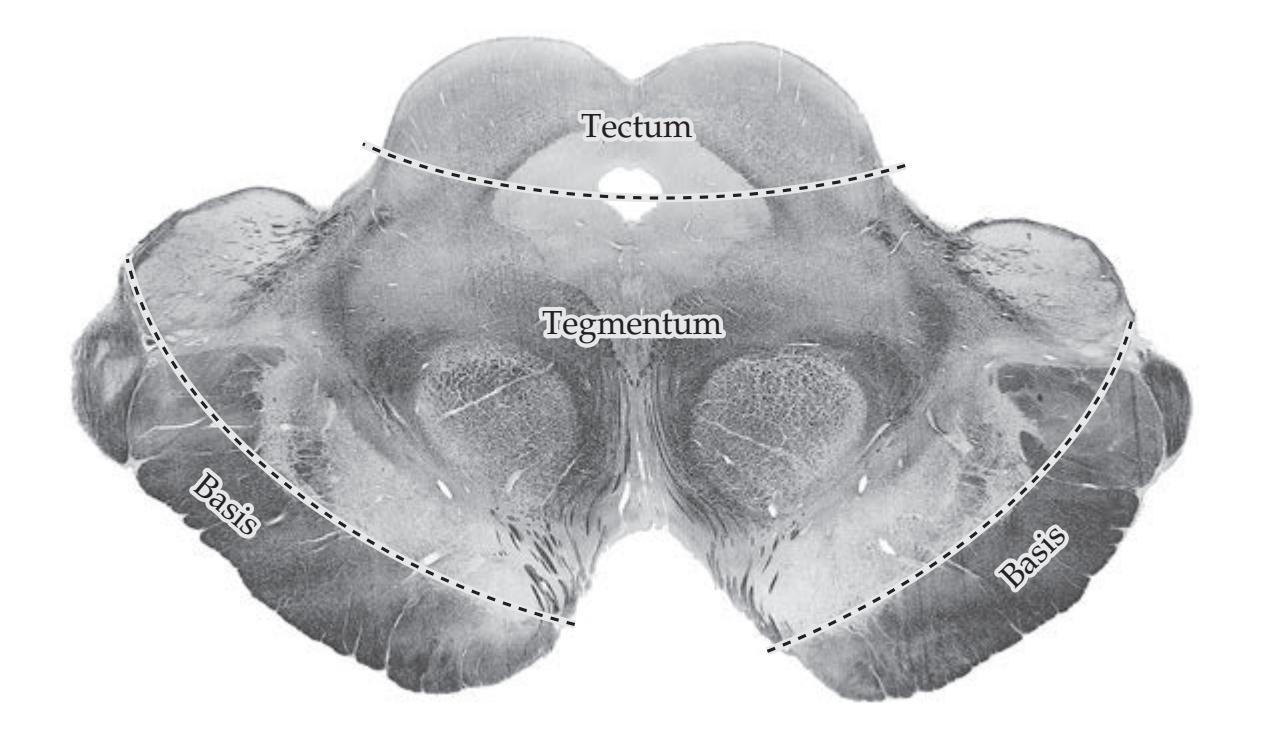

**Main Components of the Brainstem 616**

**Brainstem Sections 617**

**Cranial Nerve Nuclei and Related Structures 624**

**Long Tracts 626**

**KCC 14.1** Locked-In Syndrome 627

**Cerebellar Circuitry 627**

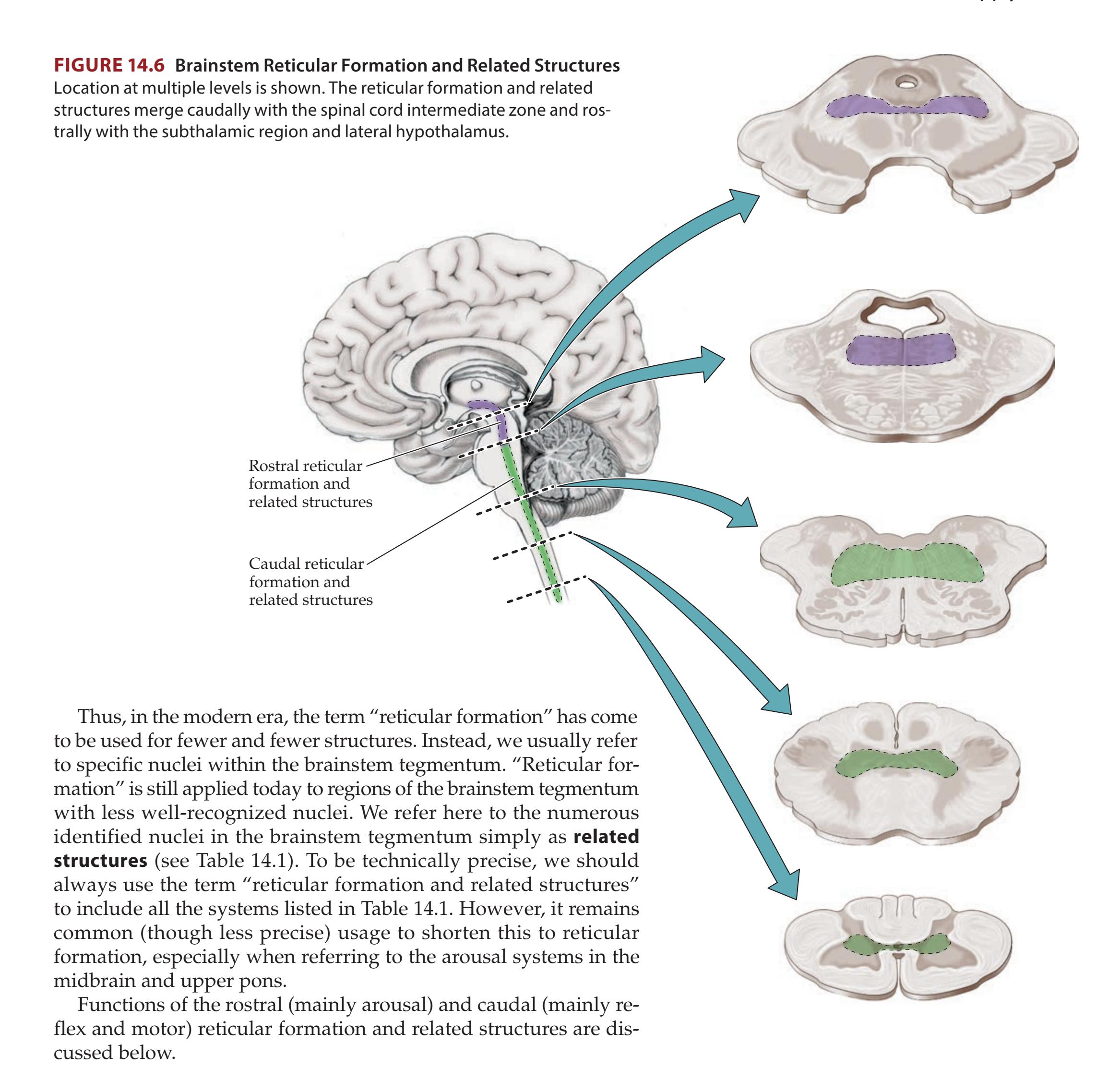

**Reticular Formation and Related Structures 628**

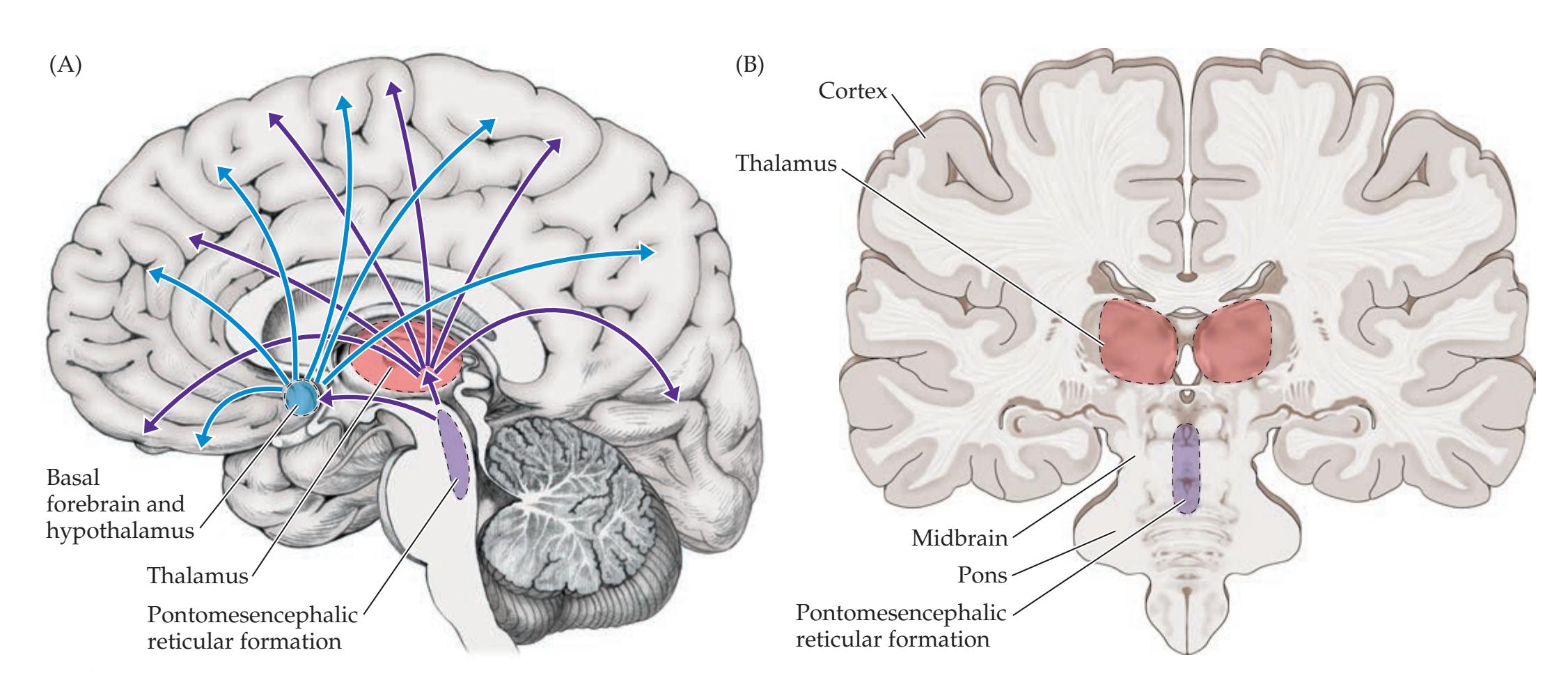

**The Consciousness System 629**

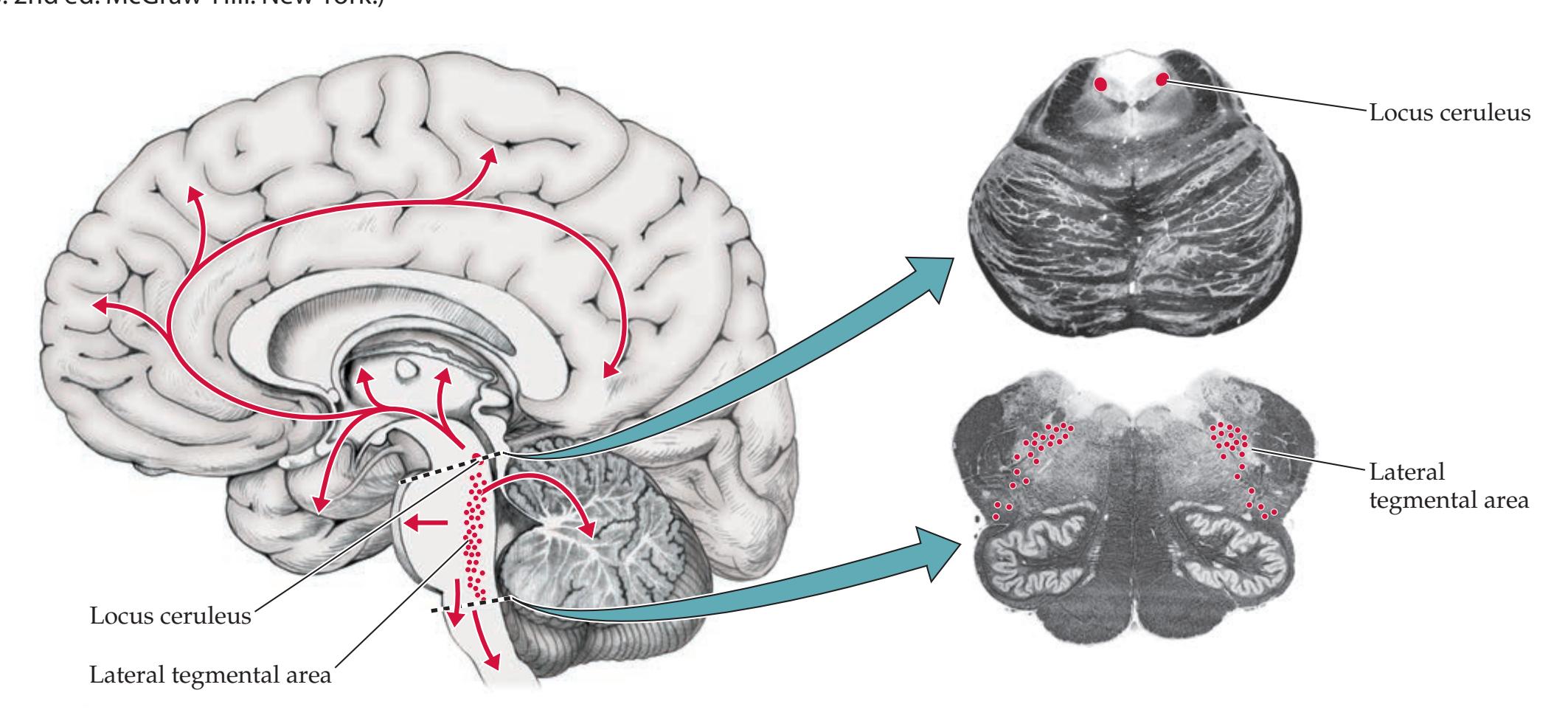

**Widespread Projection Systems of Brainstem and Forebrain: Consciousness, Attention, and Other Functions 632**

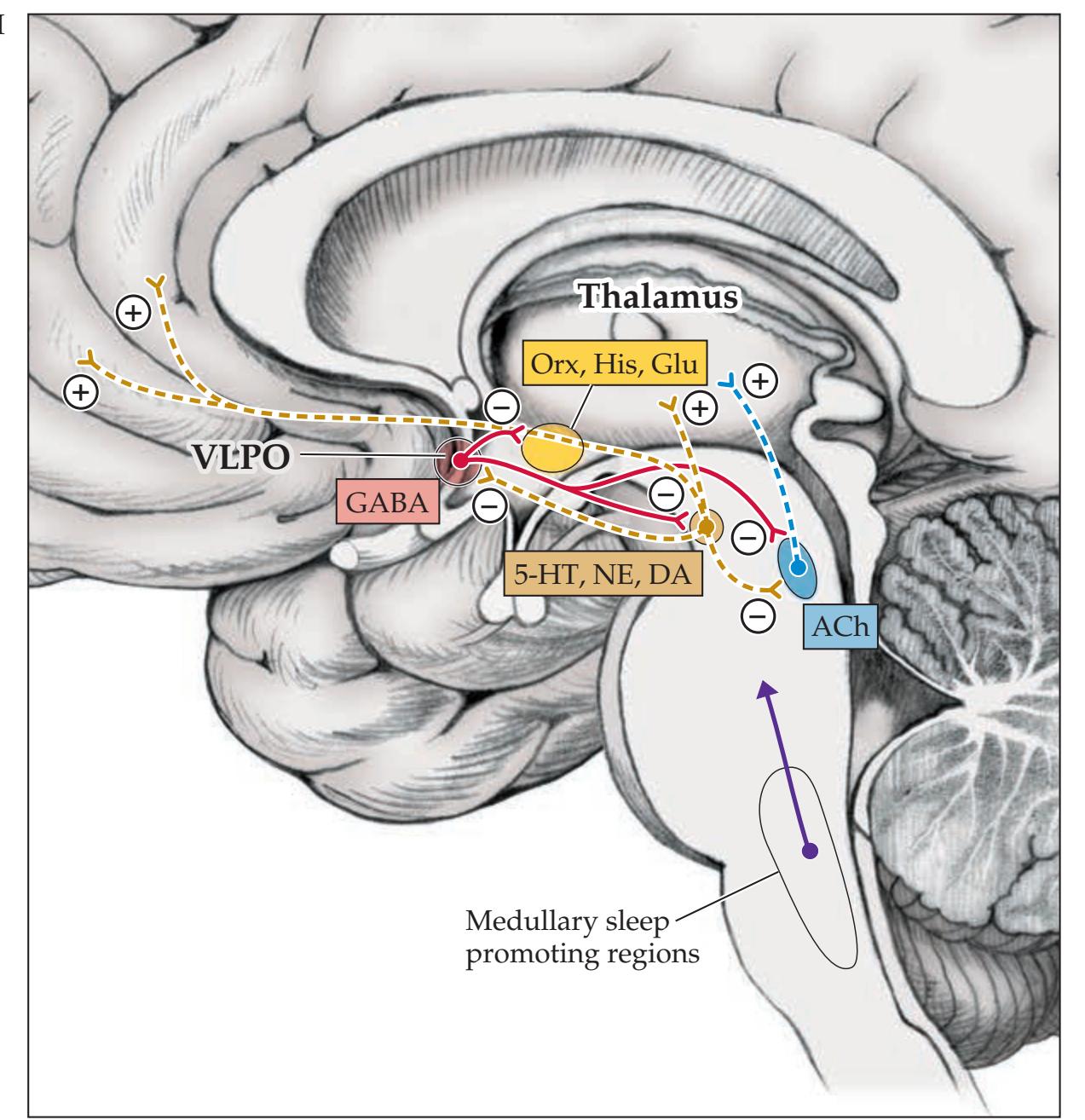

**Anatomy of the Sleep–Wake Cycle 638**

**KCC 14.2** Coma and Related Disorders 642

**Other Brainstem Motor, Reflex, and Autonomic Systems 648**

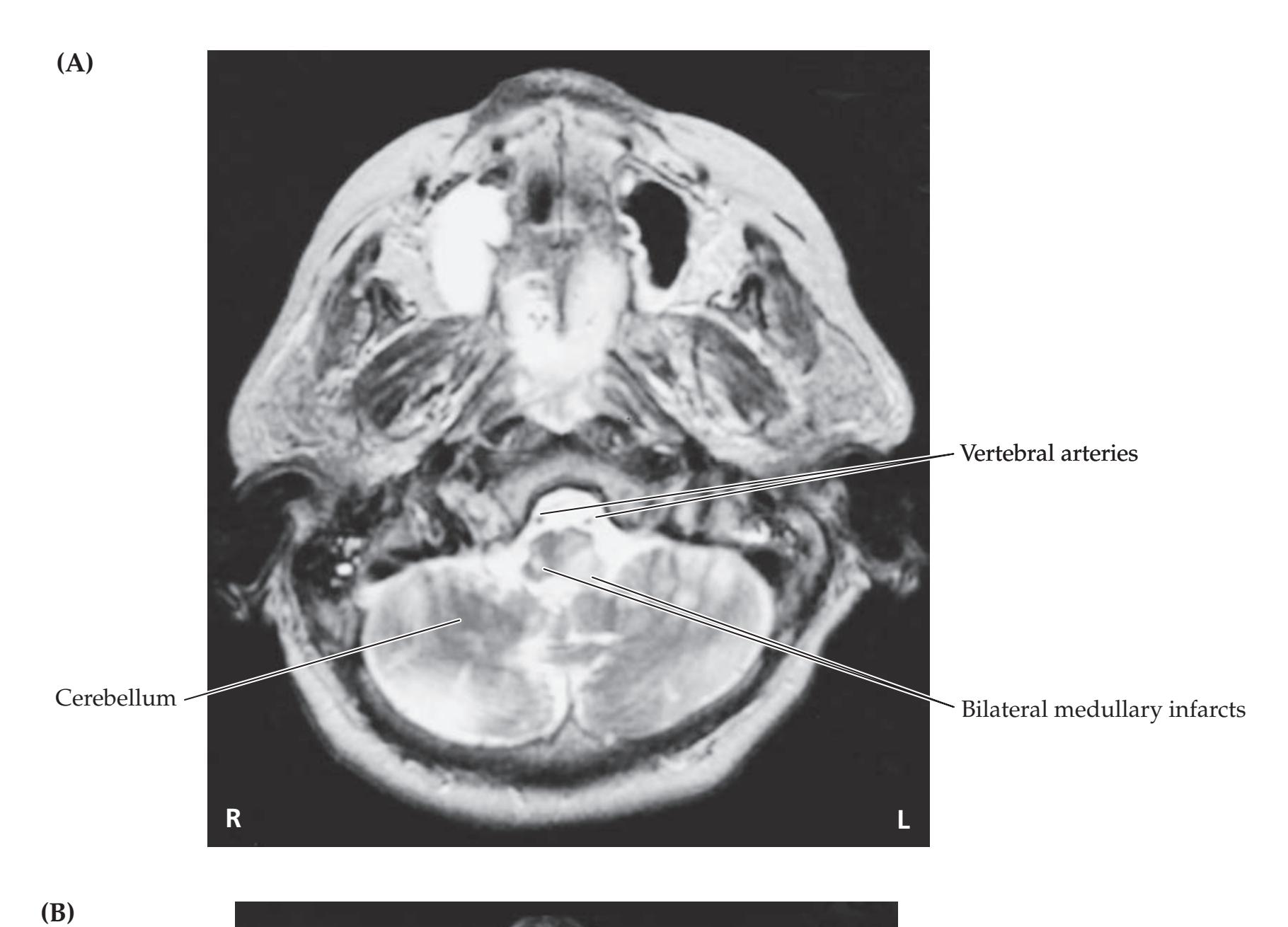

**Brainstem Vascular Supply 650**

**KCC 14.3** Vertebrobasilar Vascular Disease 656

### **CLINICAL CASES 663**

- **14.1** Face and Contralateral Body Numbness, Hoarseness, Horner's Syndrome, and Ataxia 663

- **14.2** Hemiparesis Sparing the Face 665

- **14.3** Dysarthria and Hemiparesis 670

- **14.4** Unilateral Face Numbness, Hearing Loss, and Ataxia 671

- **14.5** Locked-In 675

- **14.6** Wrong-Way Eyes, Limited Upgaze, Decreased Responsiveness, and Hemiparesis with an Amazing Recovery 677

- **14.7** Diplopia and Unilateral Ataxia 684

- **14.8** Intermittent Memory Loss, Diplopia, Sparkling Lights, and Somnolence 685

- **14.9** Intractable Hiccups 689

**Additional Cases 690**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 694**

**References 695**

Contents **xiii**

## Chapter 15 *Cerebellum 699*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 700**

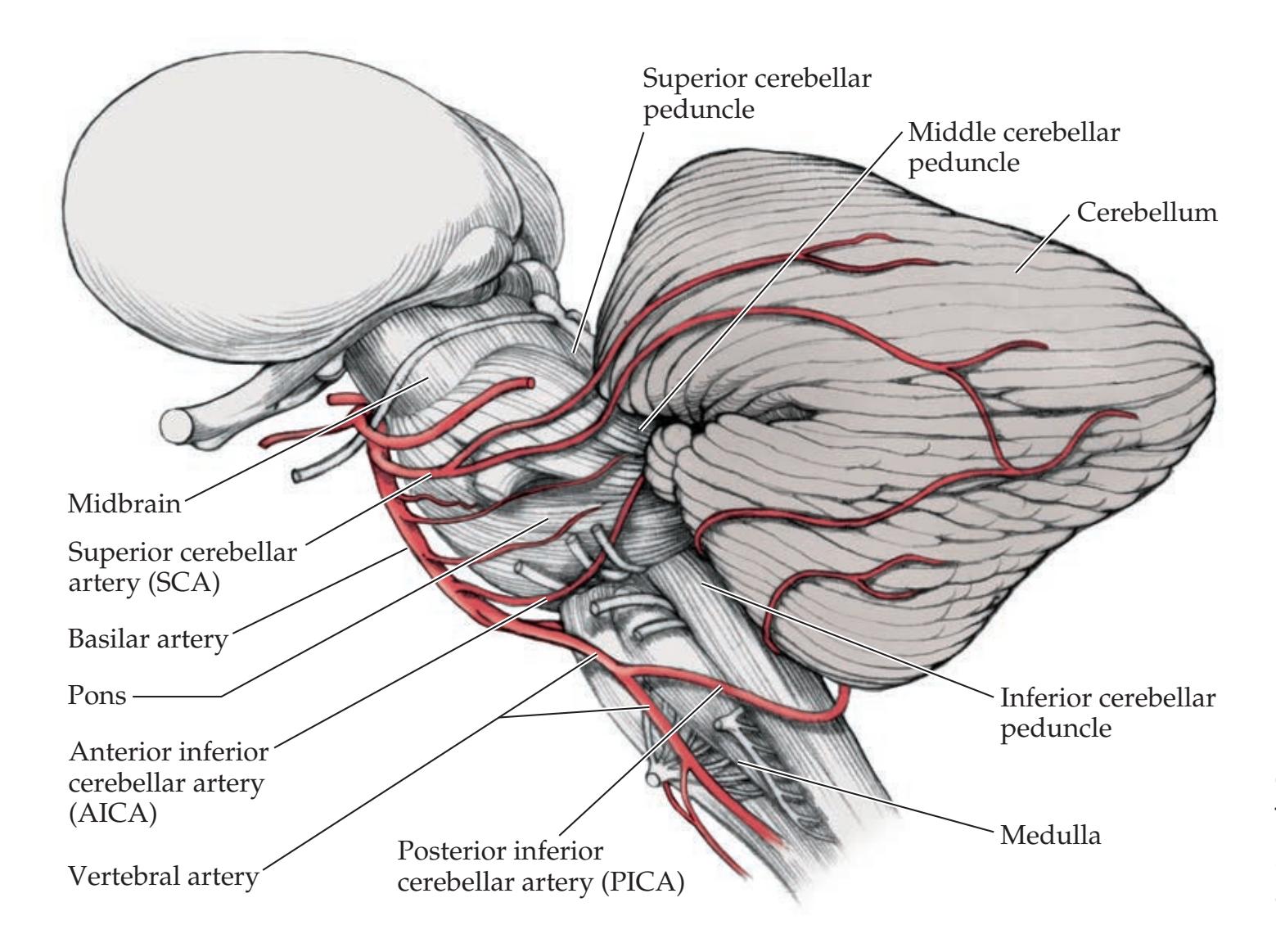

**Cerebellar Lobes, Peduncles, and Deep Nuclei 700**

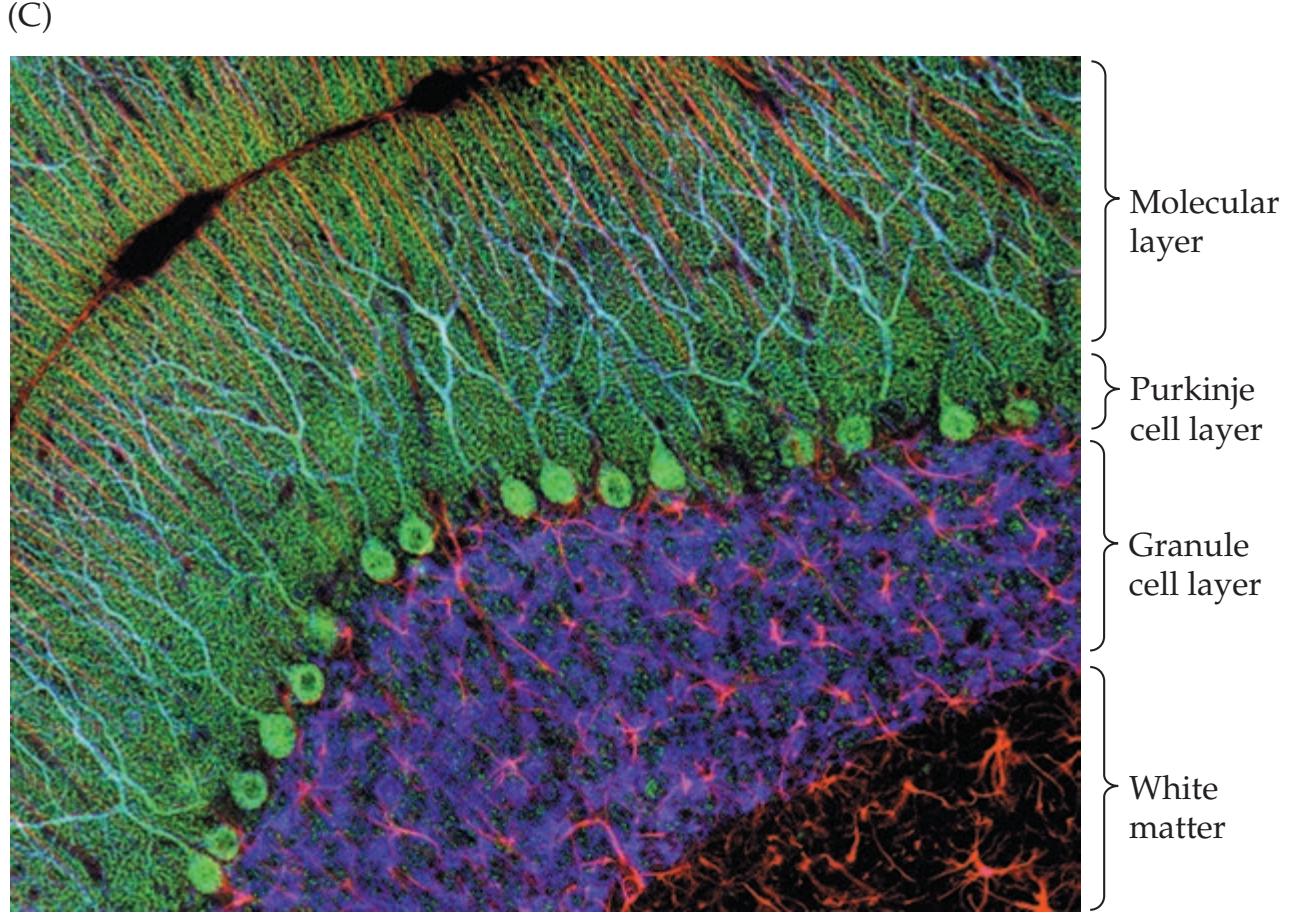

**Microscopic Circuitry of the Cerebellum 705**

**Cerebellar Output Pathways 707**

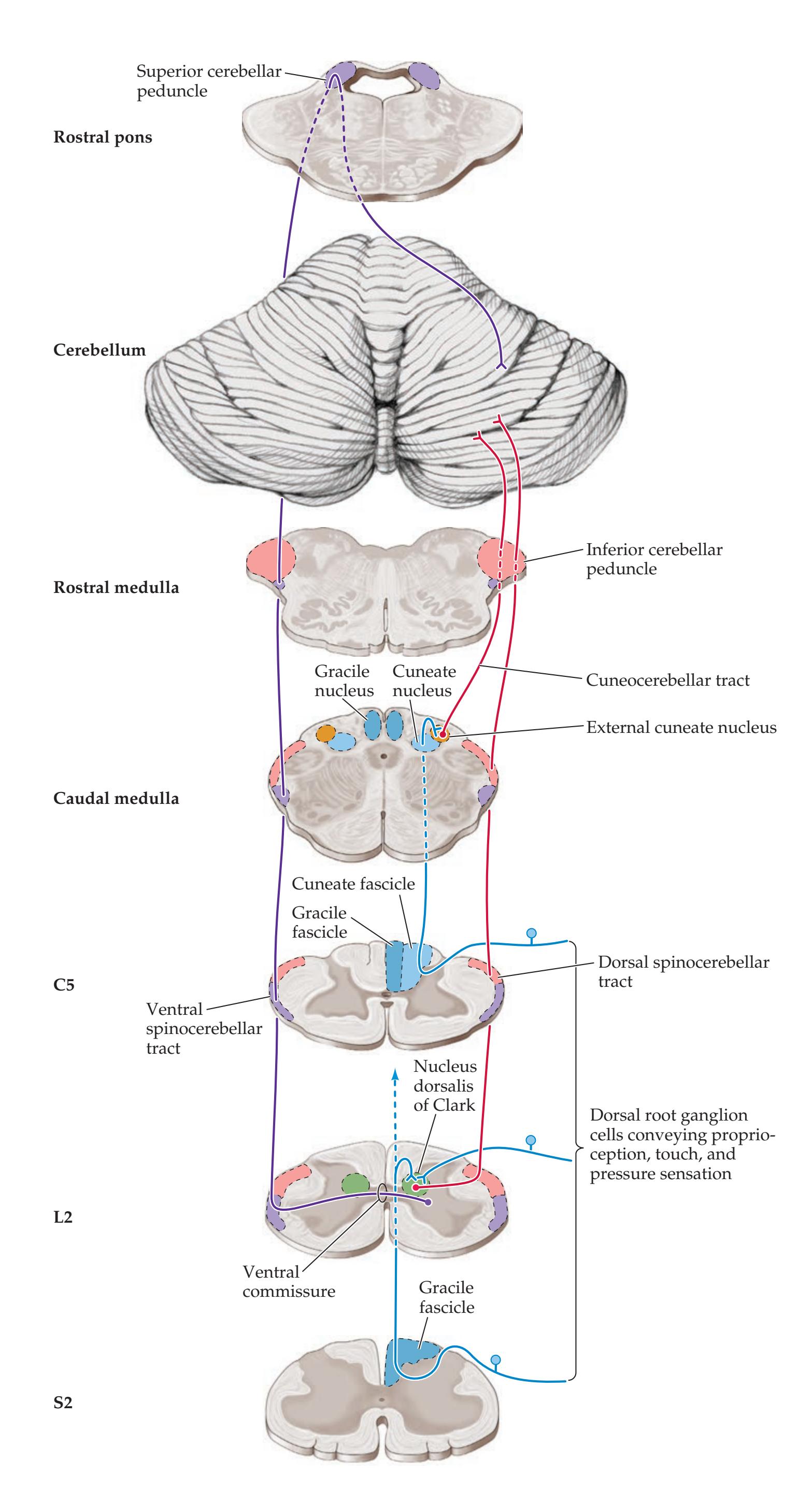

**Cerebellar Input Pathways 710**

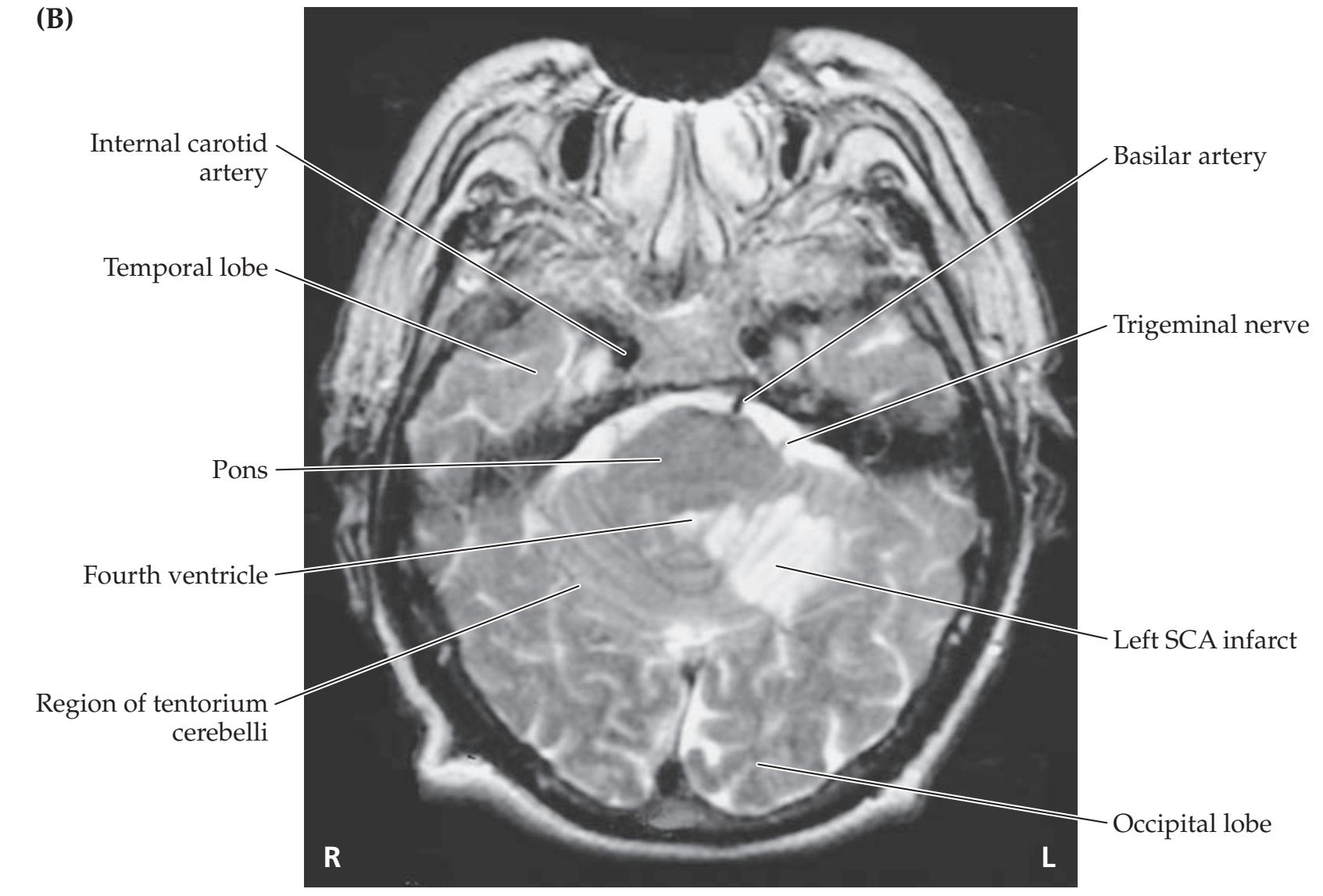

**Vascular Supply to the Cerebellum 713**

**KCC 15.1** Cerebellar Artery Infarcts and Cerebellar Hemorrhage 715

**KCC 15.2** Clinical Findings and Localization of Cerebellar Lesions 716

**KCC 15.3** Differential Diagnosis of Ataxia 721

### **CLINICAL CASES 722**

- **15.1** Sudden Onset of Unilateral Ataxia 722

- **15.2** Walking Like a Drunkard 723

- **15.3** A Boy with Headaches, Nausea, Slurred Speech, and Ataxia 727

- **15.4** Nausea, Progressive Unilateral Ataxia, and Right Face Numbness 729

- **15.5** A Family with Slowly Progressive Ataxia and Dementia 733

**Additional Cases 734**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 735**

**References 738**

## Chapter 16 *Basal Ganglia 741*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 742**

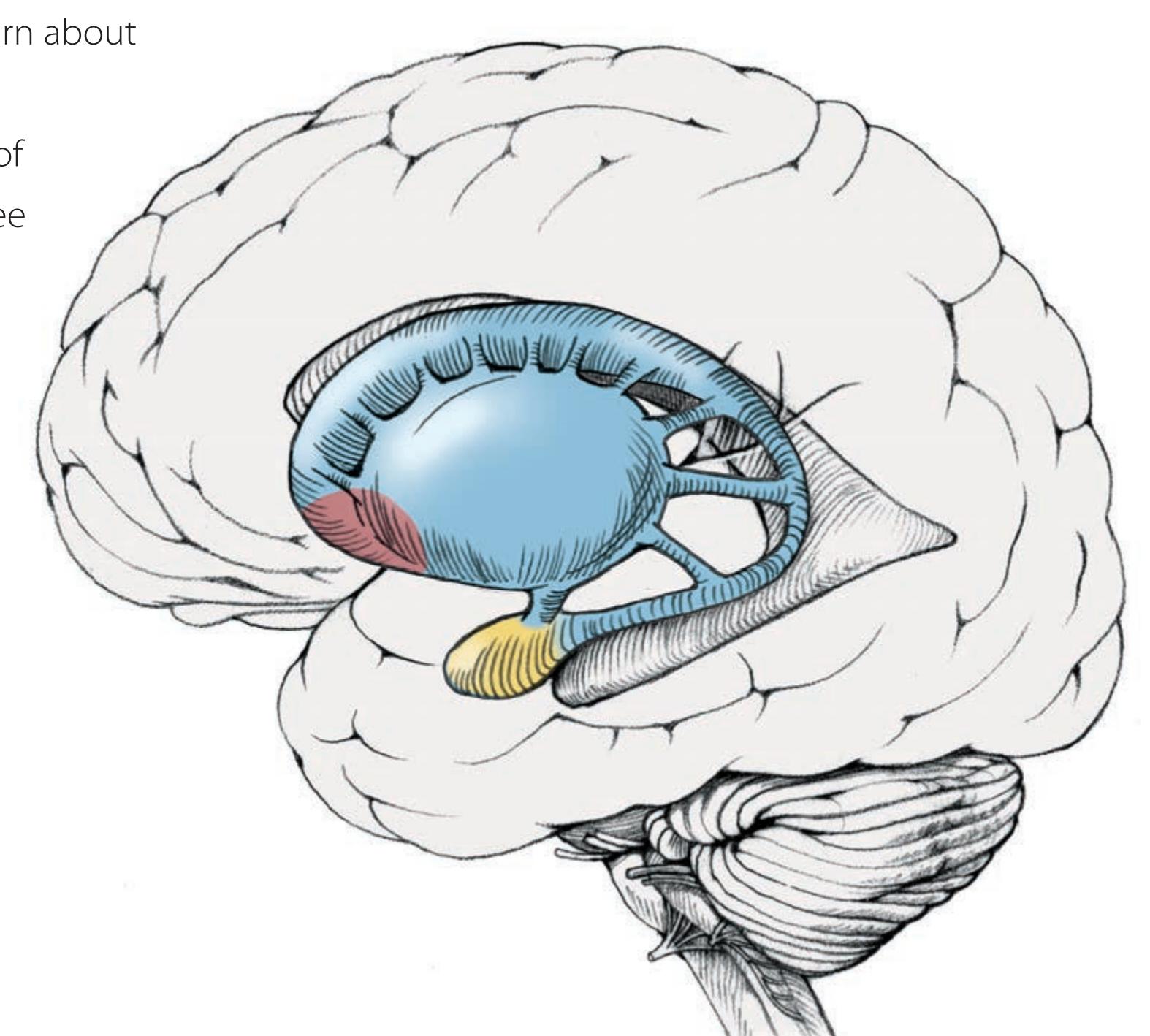

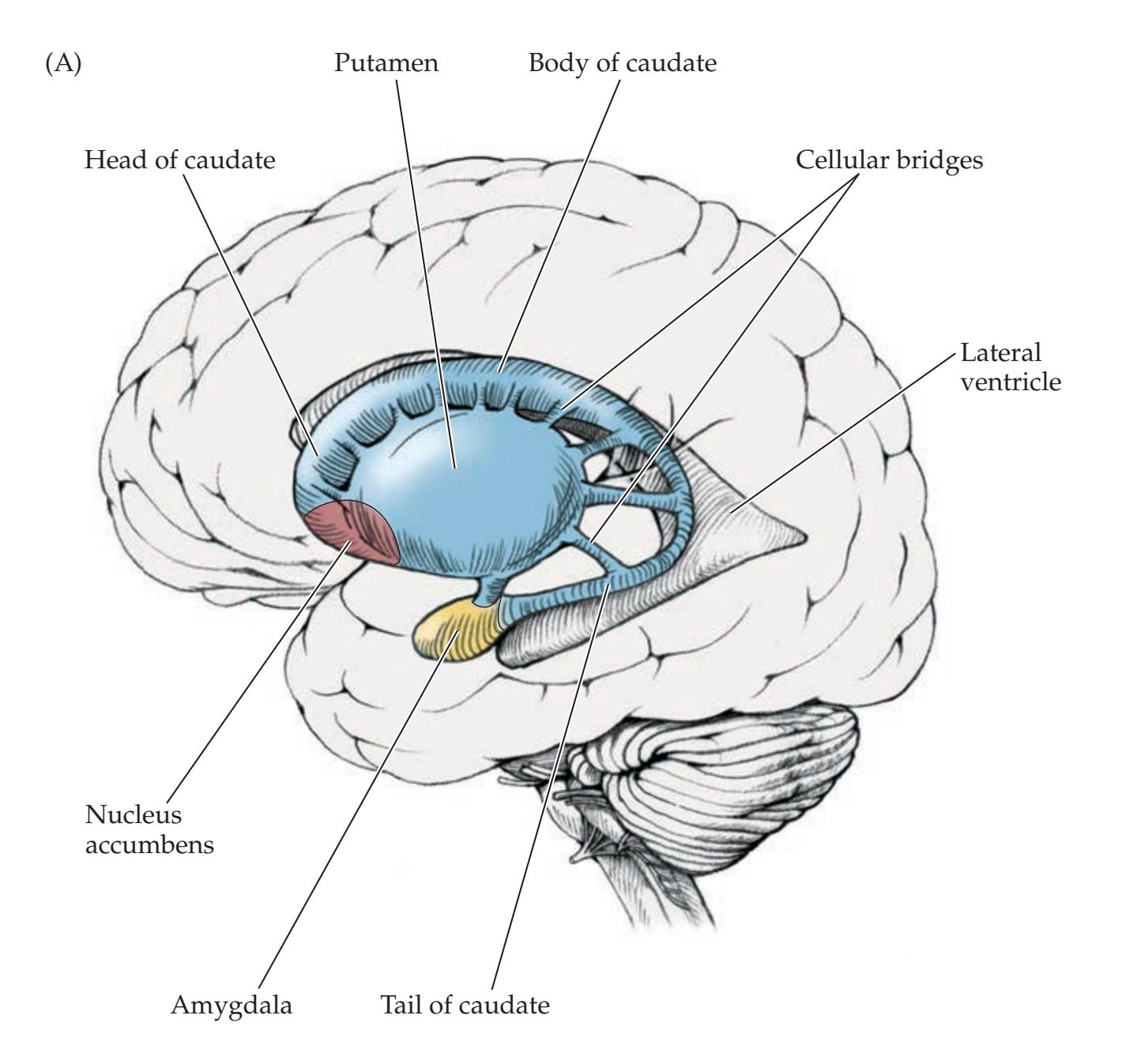

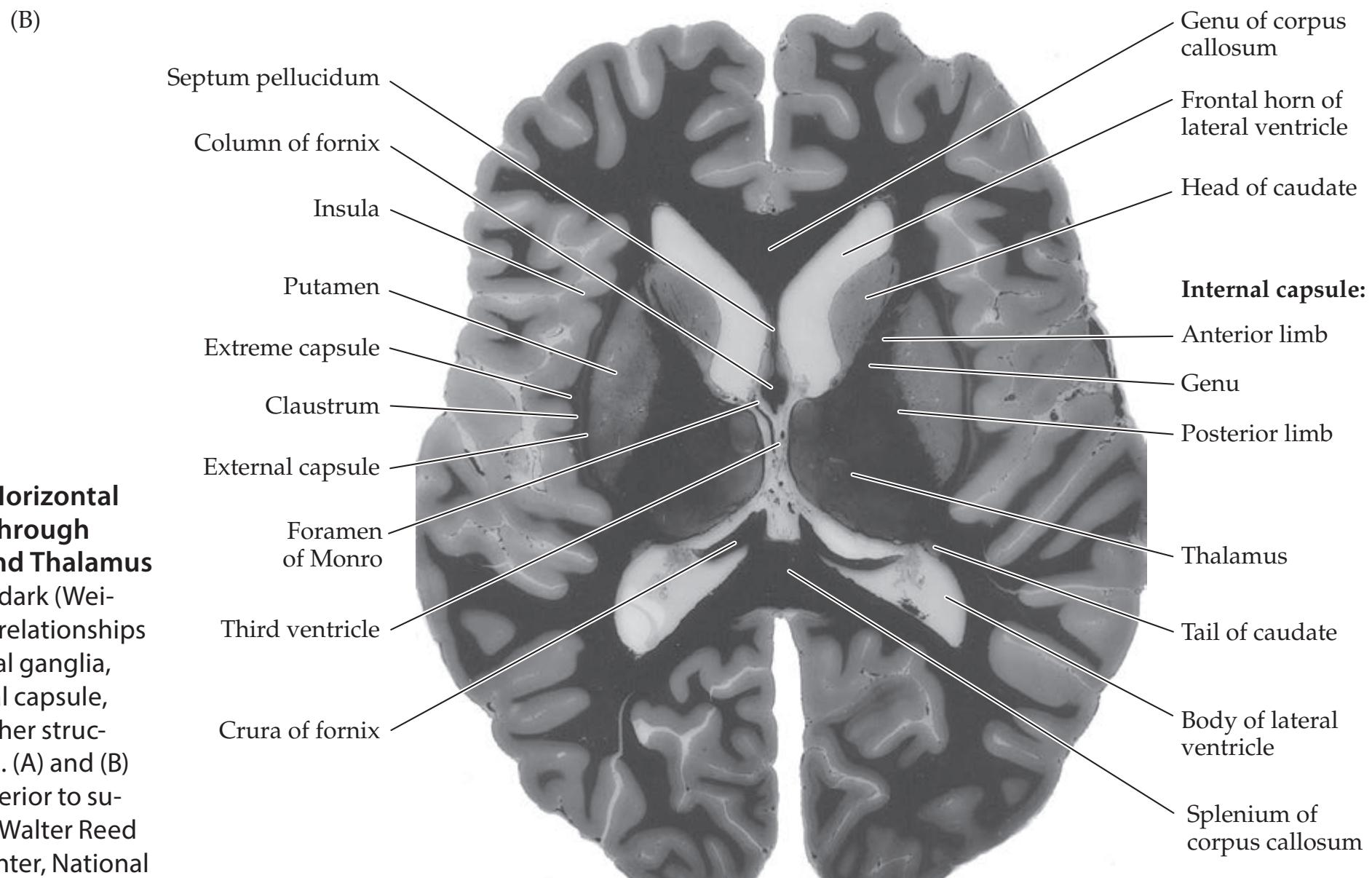

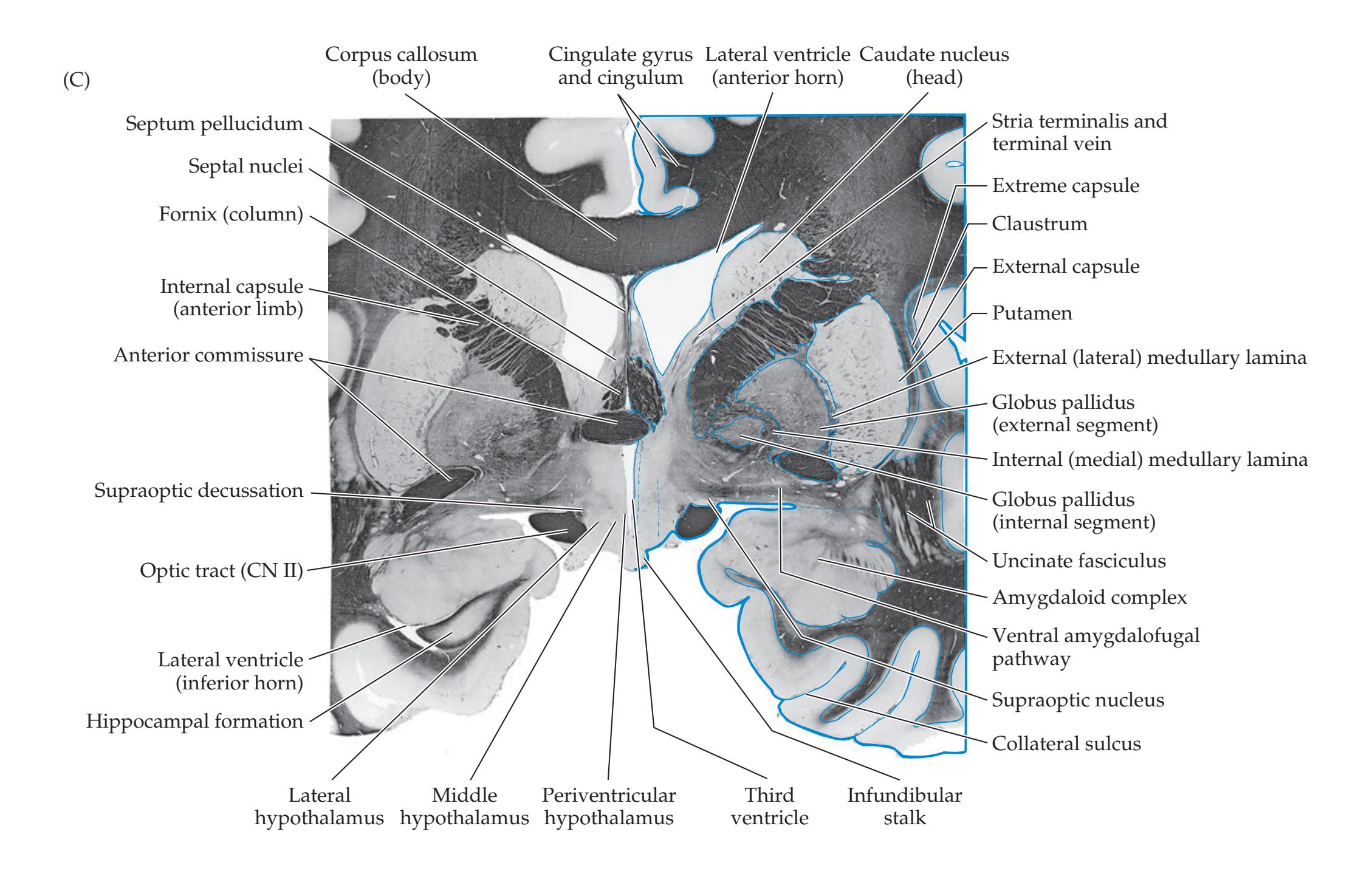

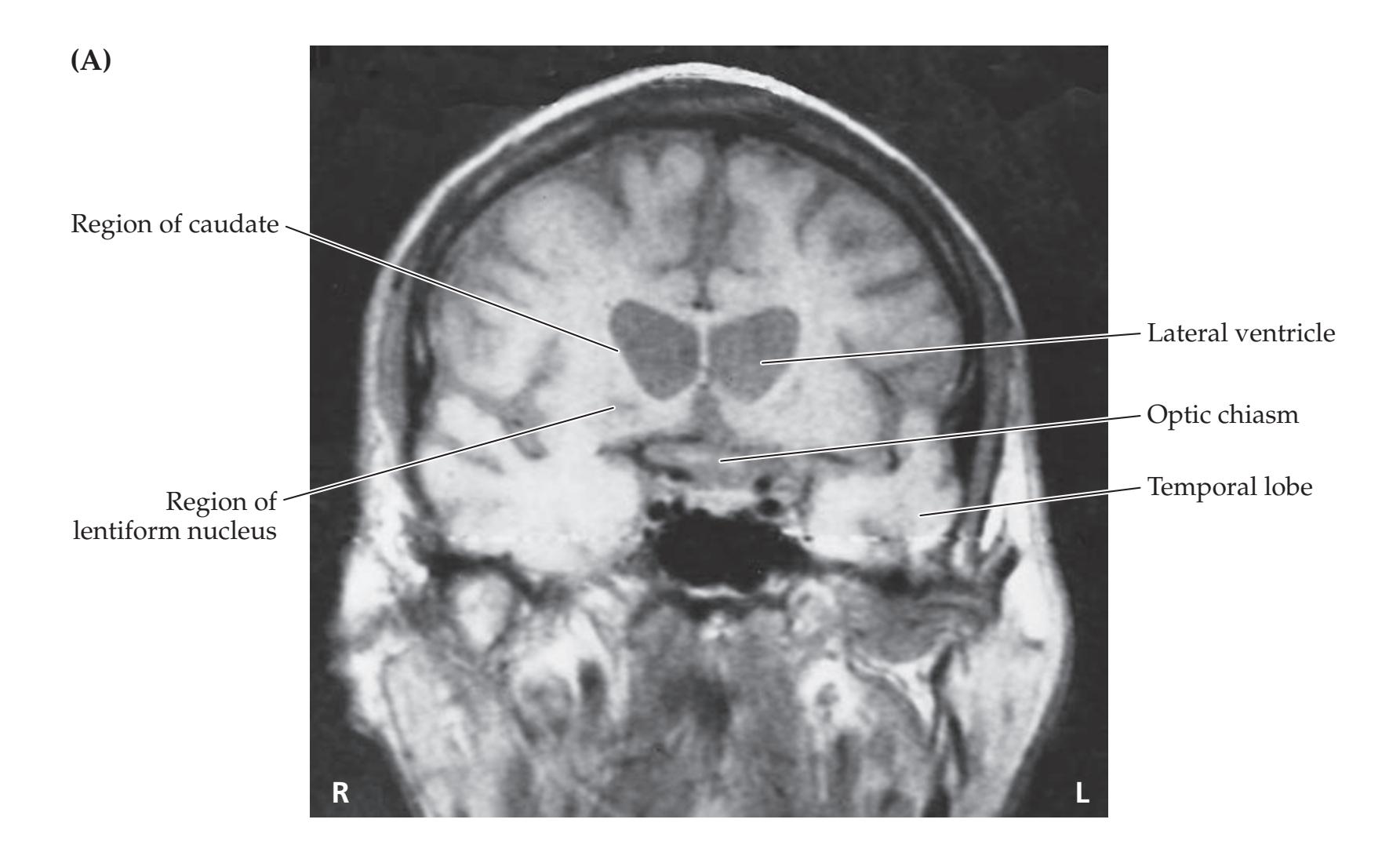

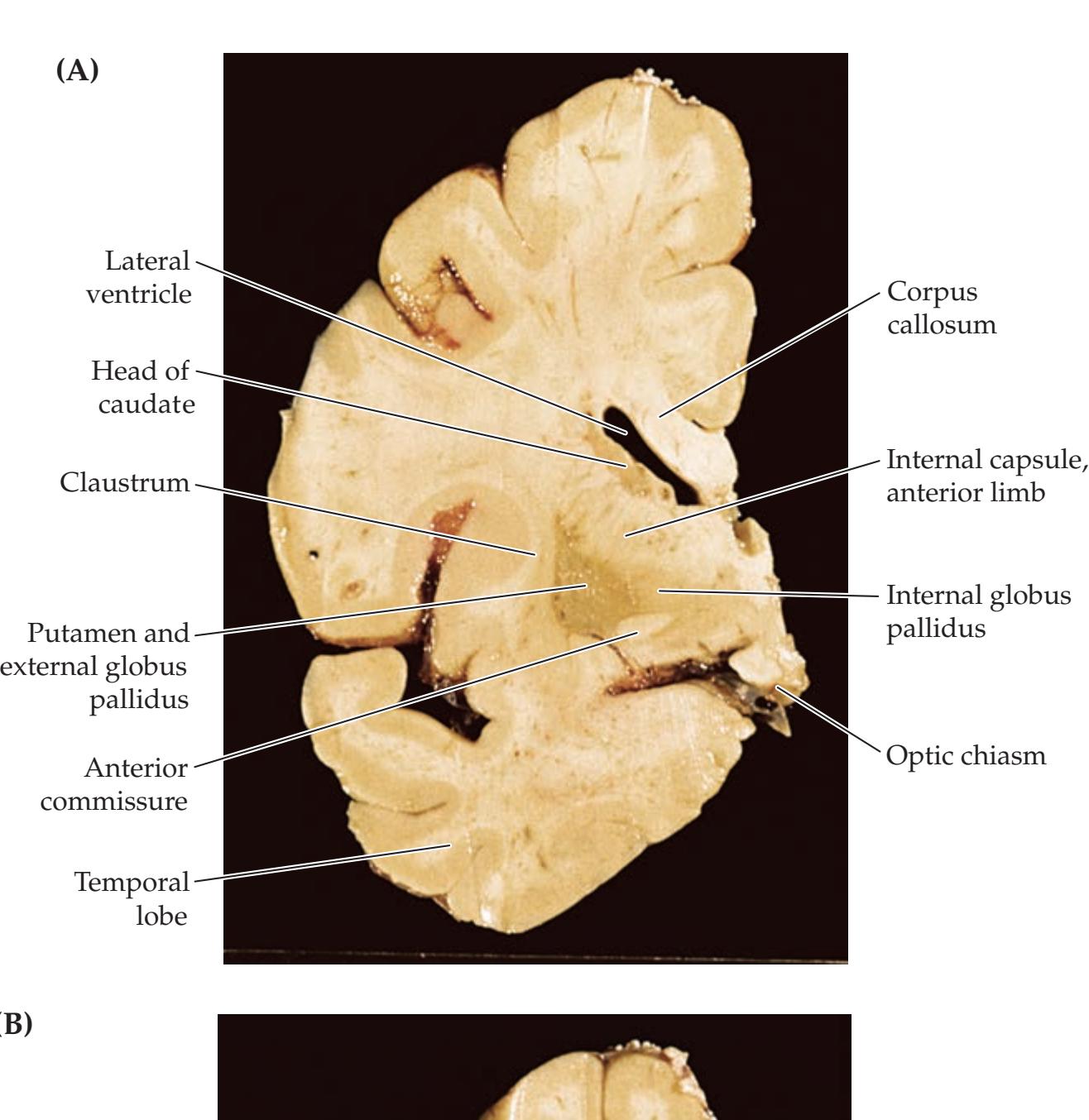

**Basic Three-Dimensional Anatomy of the Basal Ganglia 742**

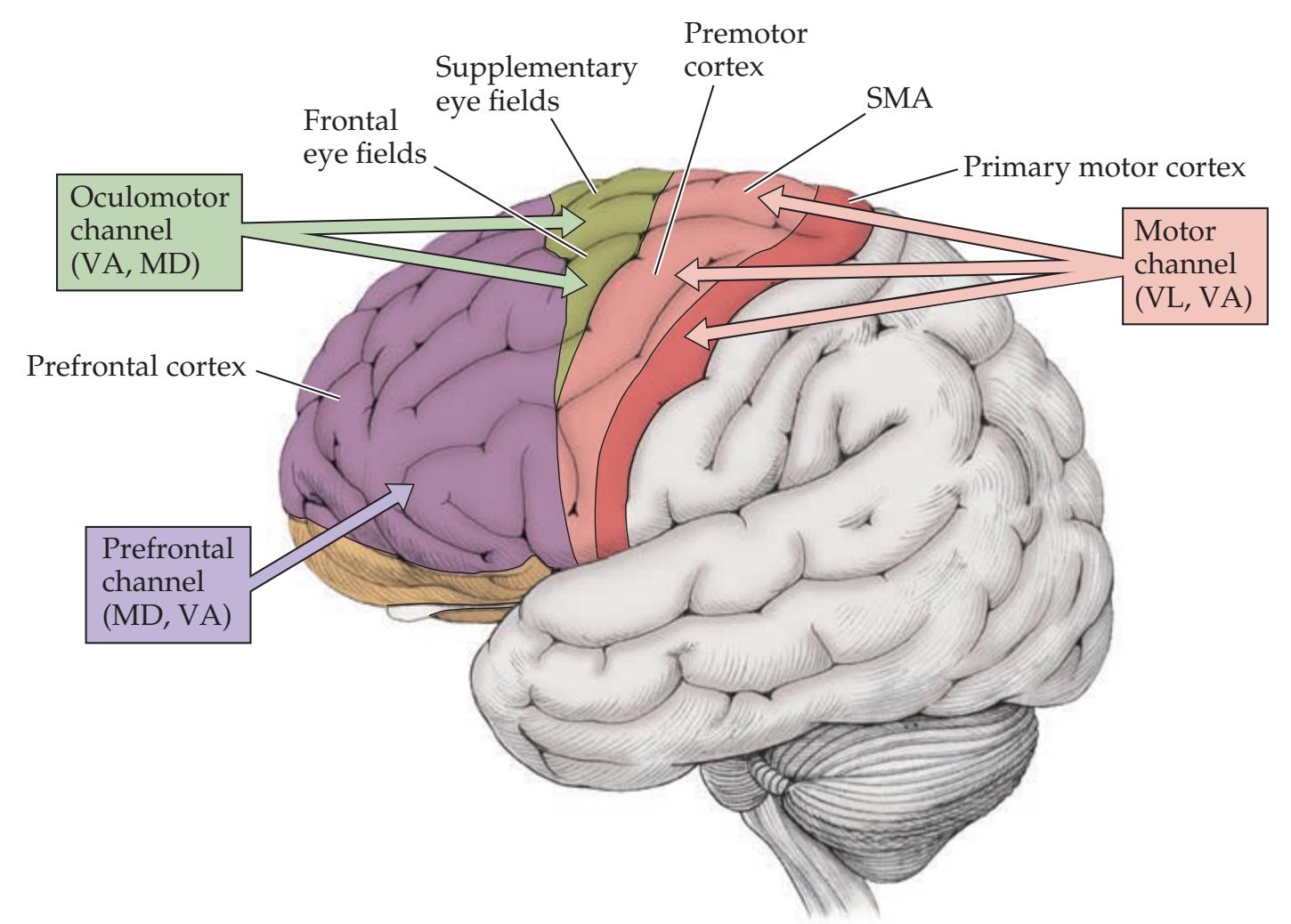

**Input, Output, and Intrinsic Connections of the Basal Ganglia 750**

**Parallel Basal Ganglia Pathways for General Movement, Eye Movement, Cognition, and Emotion 754**

**Ansa Lenticularis, Lenticular Fasciculus, and the Fields of Forel 756**

**KCC 16.1** Movement Disorders 757

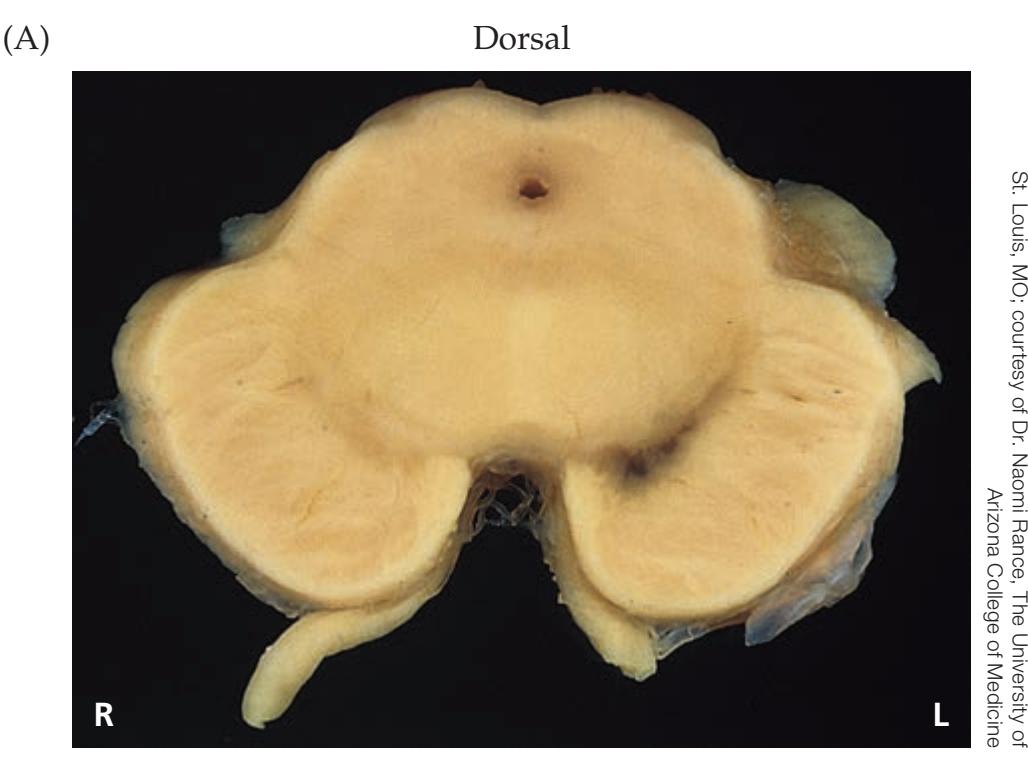

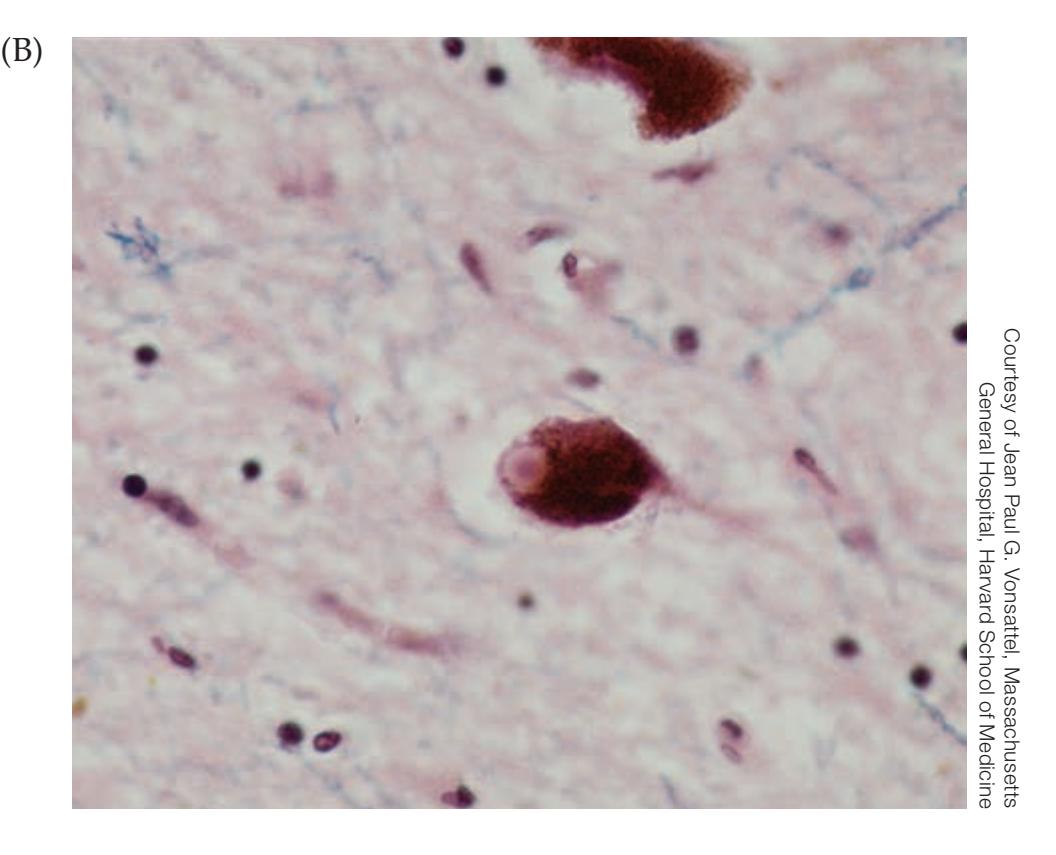

**KCC 16.2** Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders 765

**KCC 16.3** Huntington's Disease 769

**KCC 16.4** Stereotactic Neurosurgery and Deep Brain Stimulation 771

### **CLINICAL CASES 773**

- **16.1** Unilateral Flapping and Flinging 773

- **16.2** Irregular Jerking Movements and Marital Problems 774

- **16.3** Asymmetrical Resting Tremor, Rigidity, Bradykinesia, and Gait Difficulties 777

- **16.4** Bilateral Bradykinesia, Rigidity, and Gait Instability with No Tremor 781

- **16.5** Childhood Dystonia 784

**Additional Cases 789**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 789**

**References 790**

## Chapter 17 *Pituitary and Hypothalamus 795*

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 796**

**Overall Anatomy of the Pituitary and Hypothalamus 796**

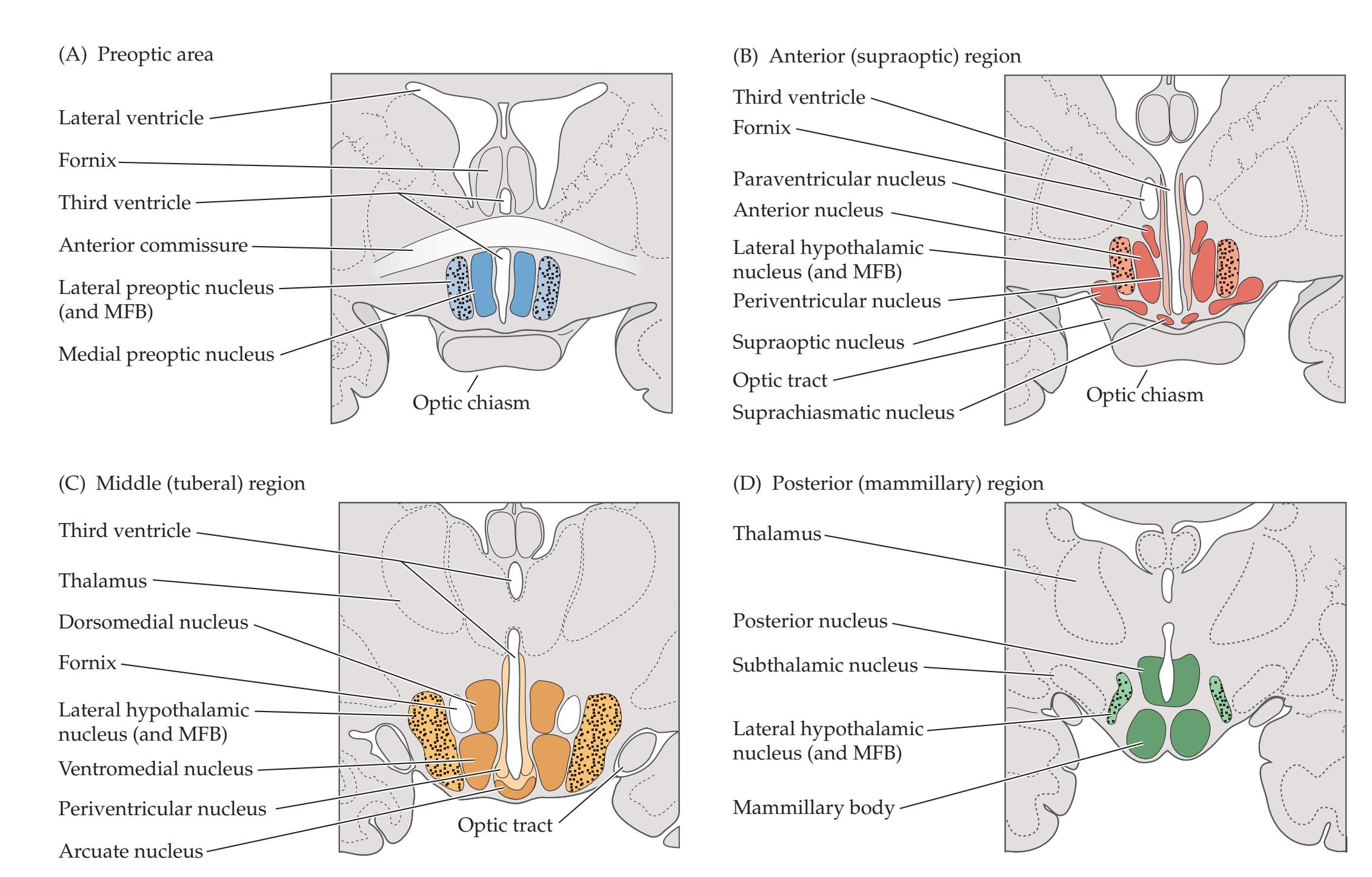

**Important Hypothalamic Nuclei and Pathways 798**

**Endocrine Functions of the Pituitary and Hypothalamus 801**

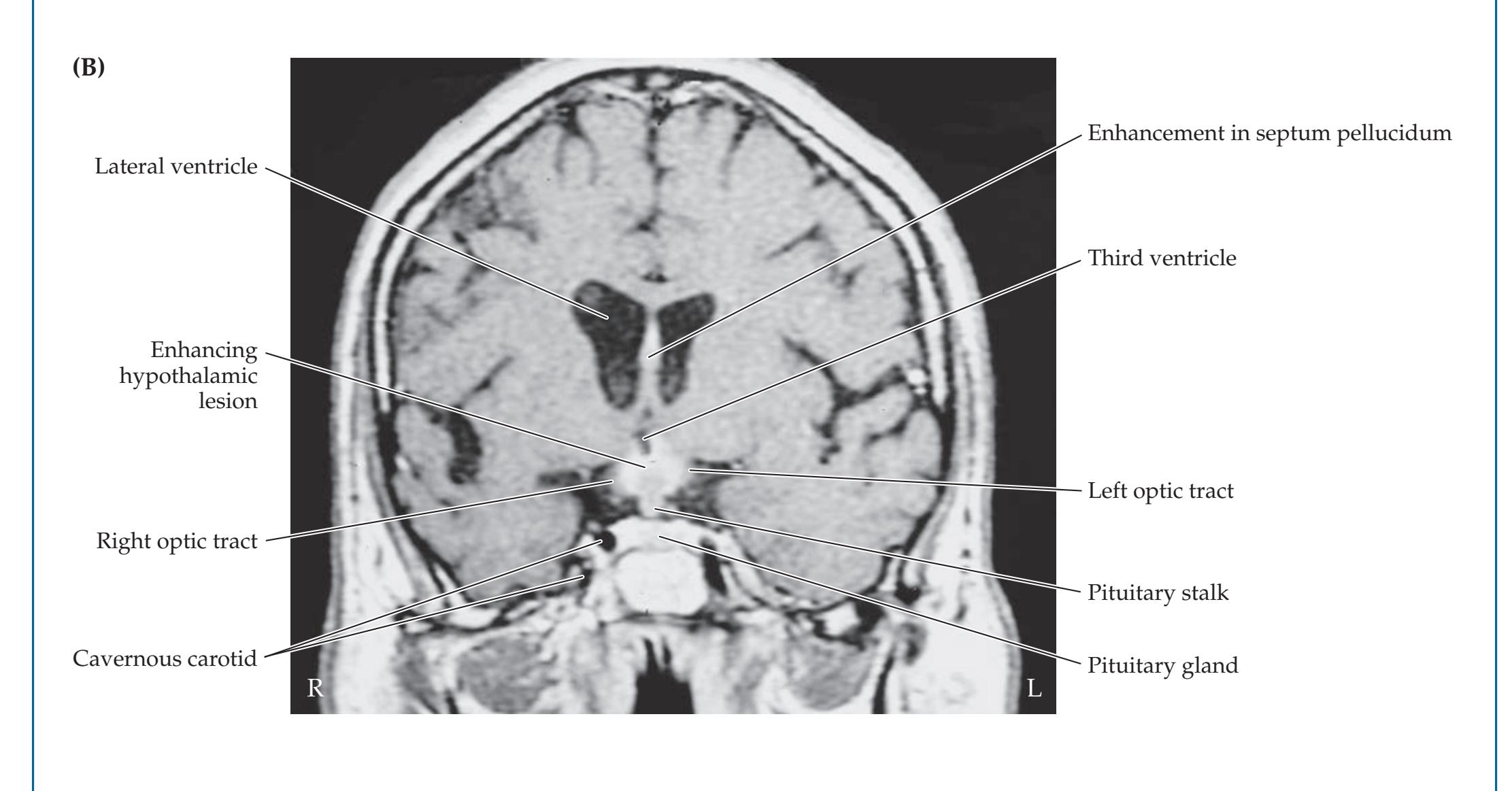

**KCC 17.1** Pituitary Adenoma and Related Disorders 804

**KCC 17.2** Diabetes Insipidus and SIADH 807

**KCC 17.3** Panhypopituitarism 808

### **CLINICAL CASES 809**

- **17.1** Moon Facies, Acne, Amenorrhea, and Hypertension 809

- **17.2** Impotence, Anorexia, Polyuria, Blurred Vision, Headaches, and Hearing Loss 813

- **17.3** A Child with Giggling Episodes and Aggressive Behavior 815

**Additional Cases 816**

**BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 819**

**References 820**

**xiv** Contents

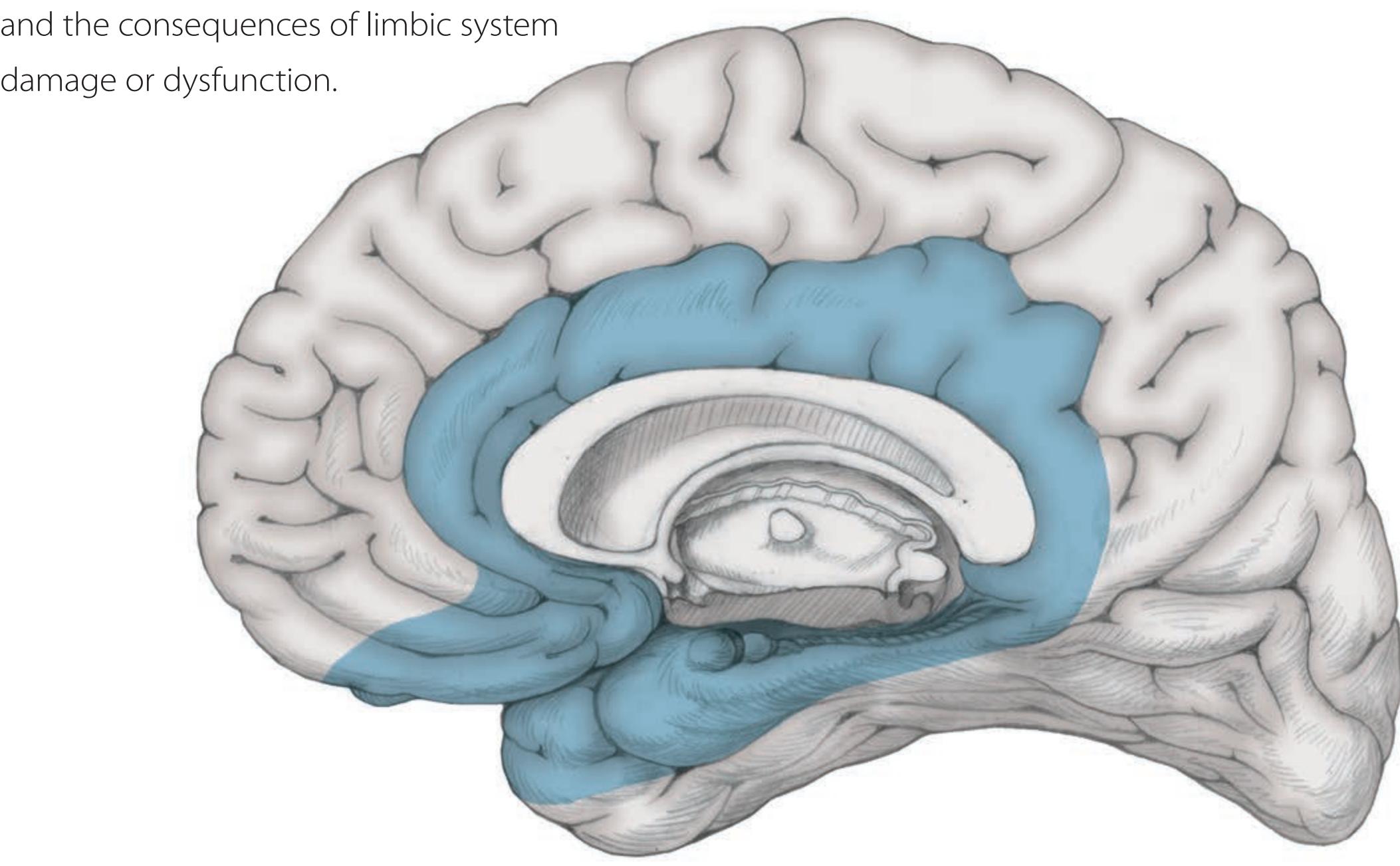

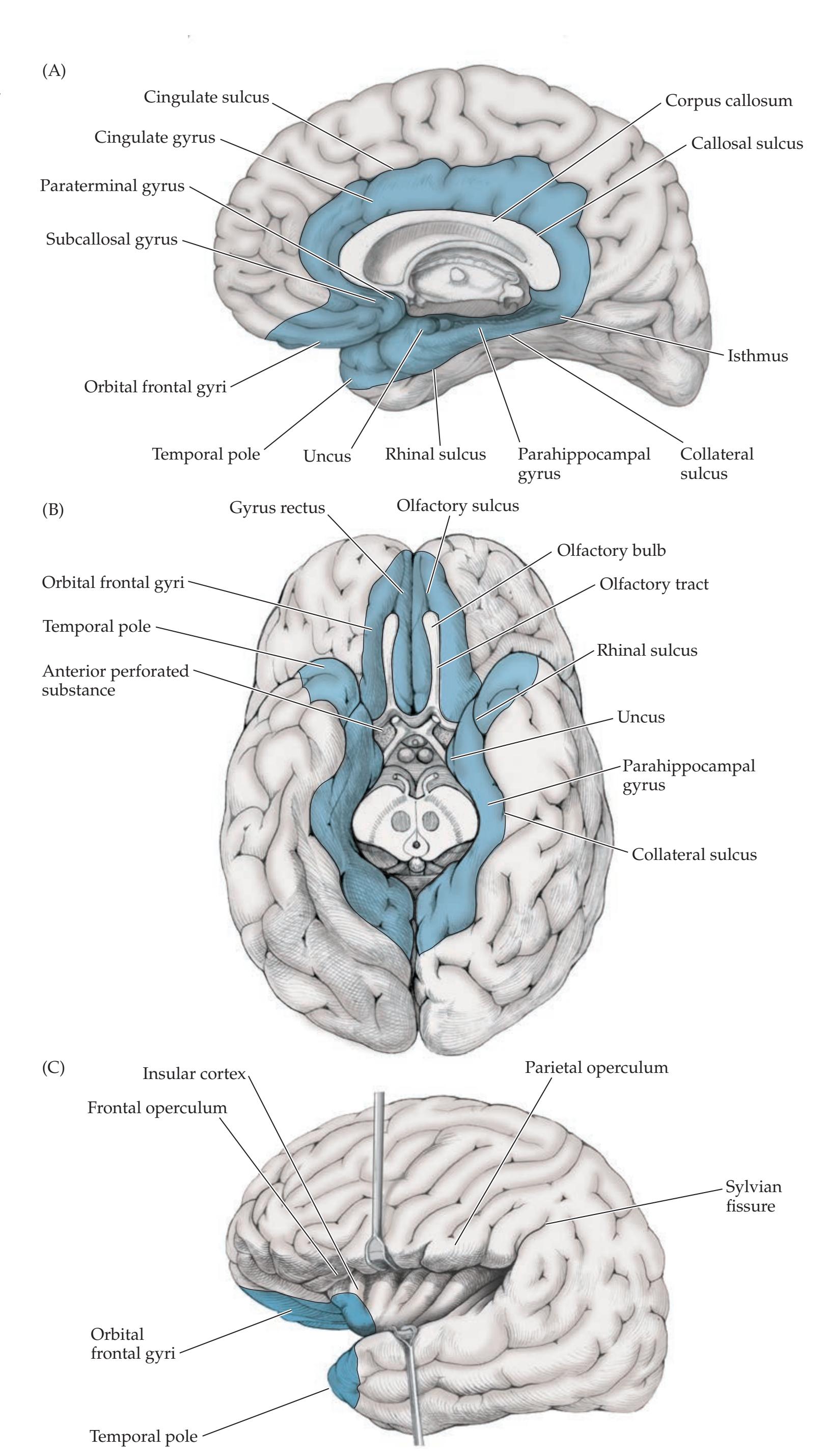

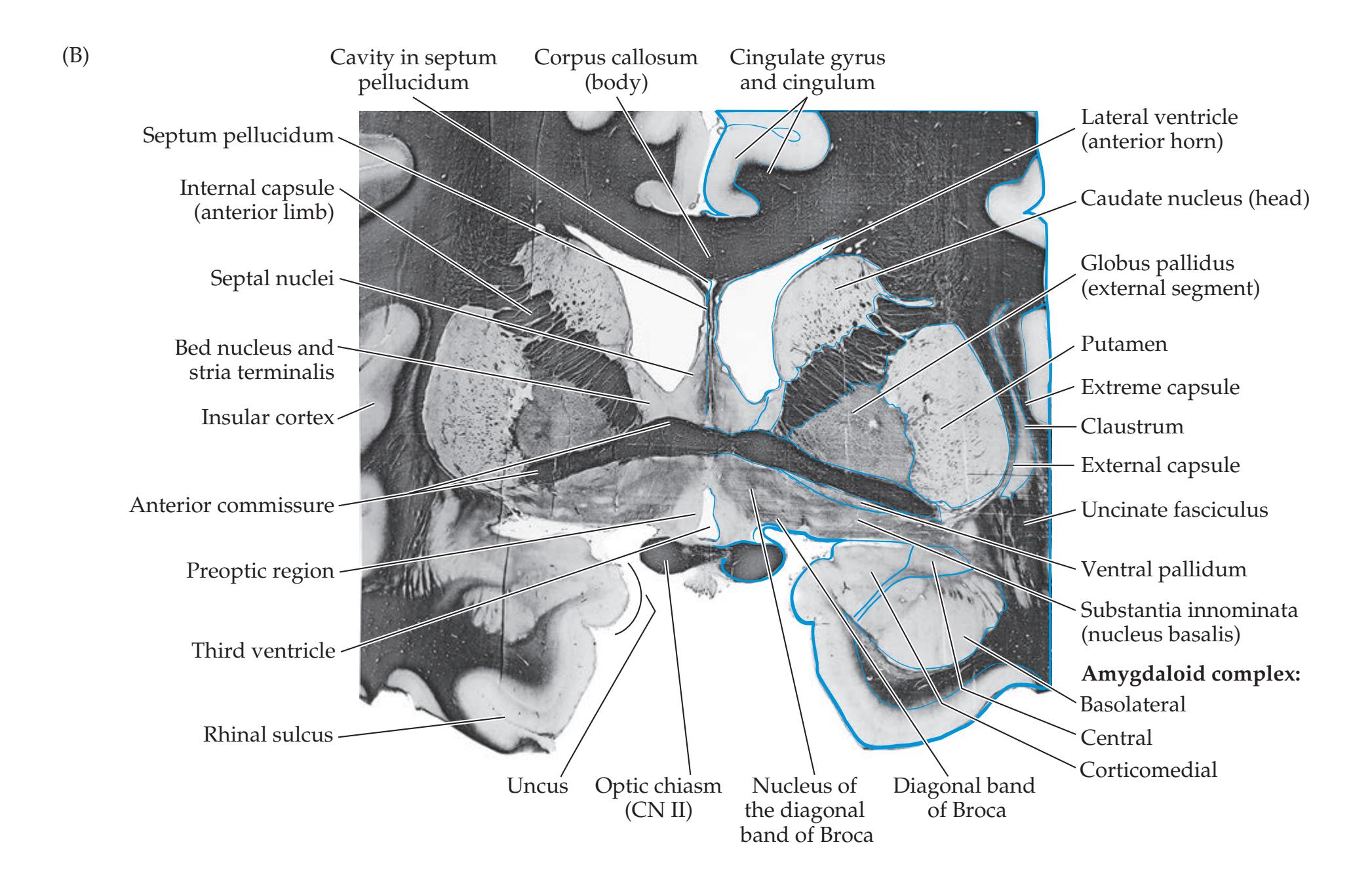

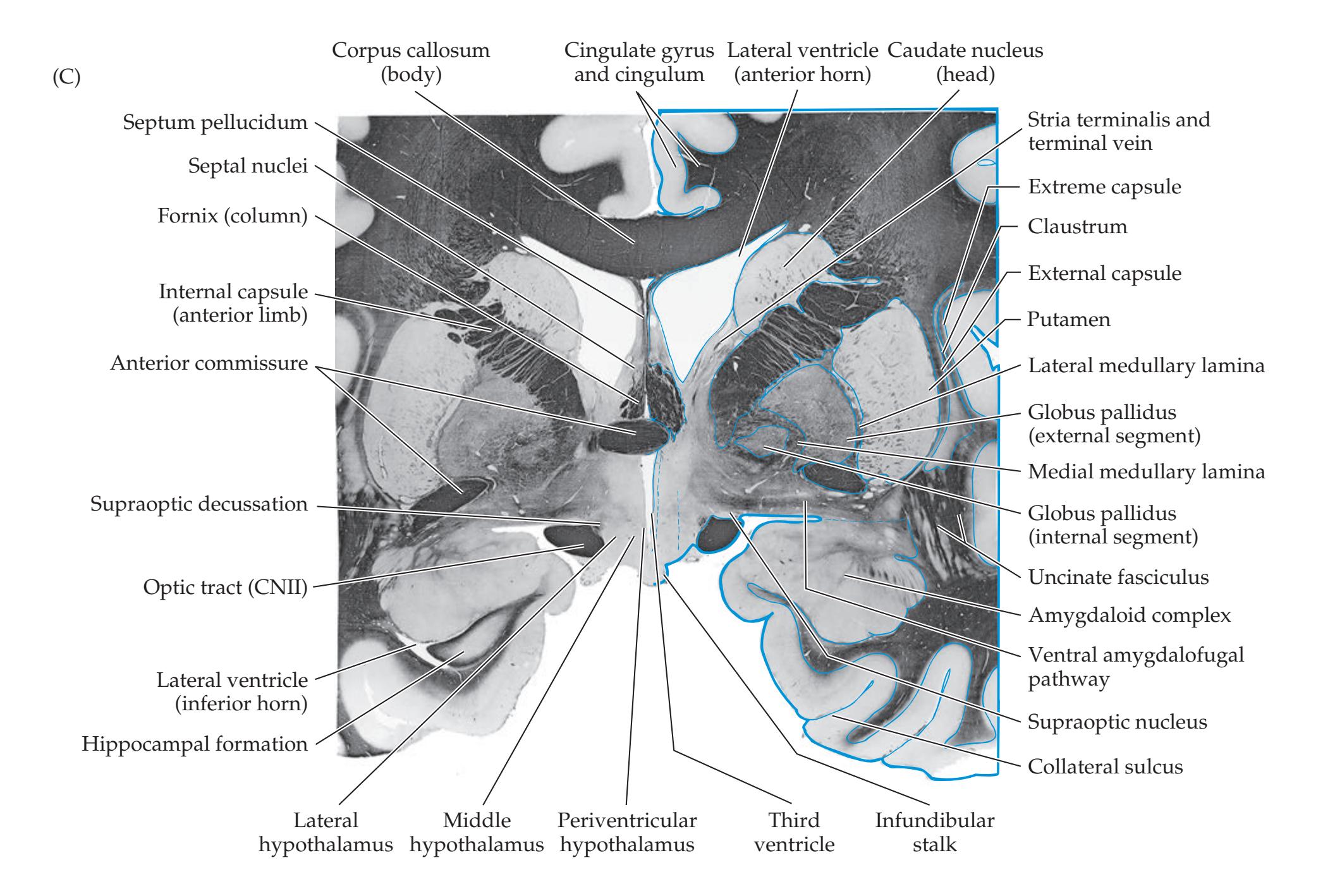

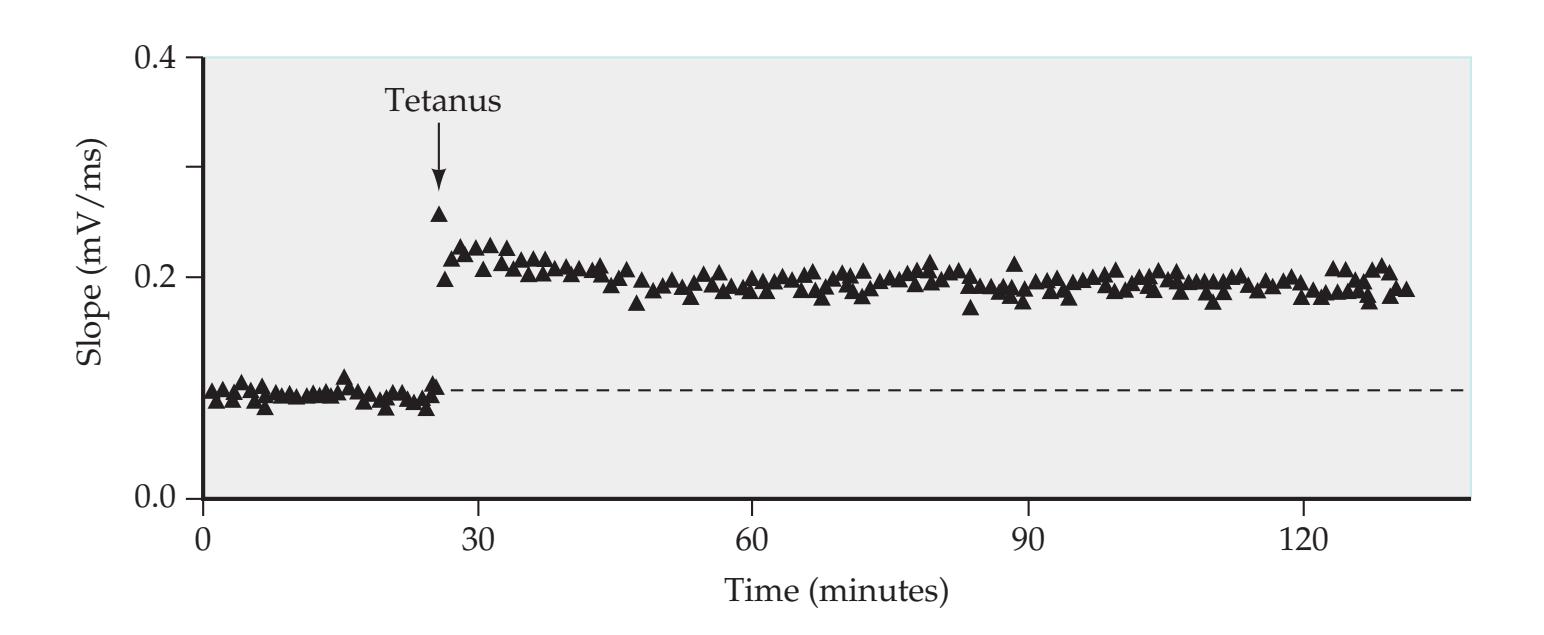

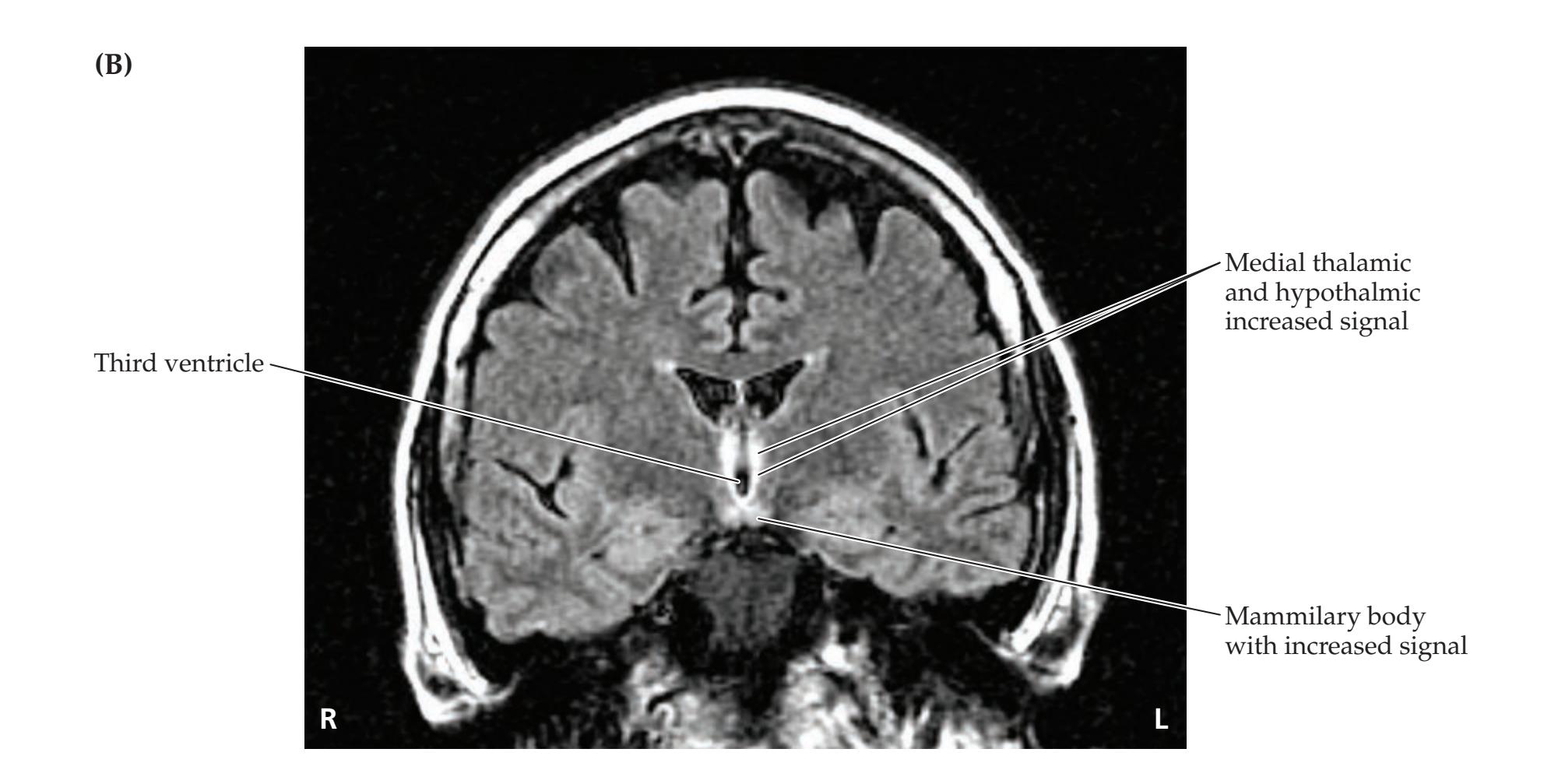

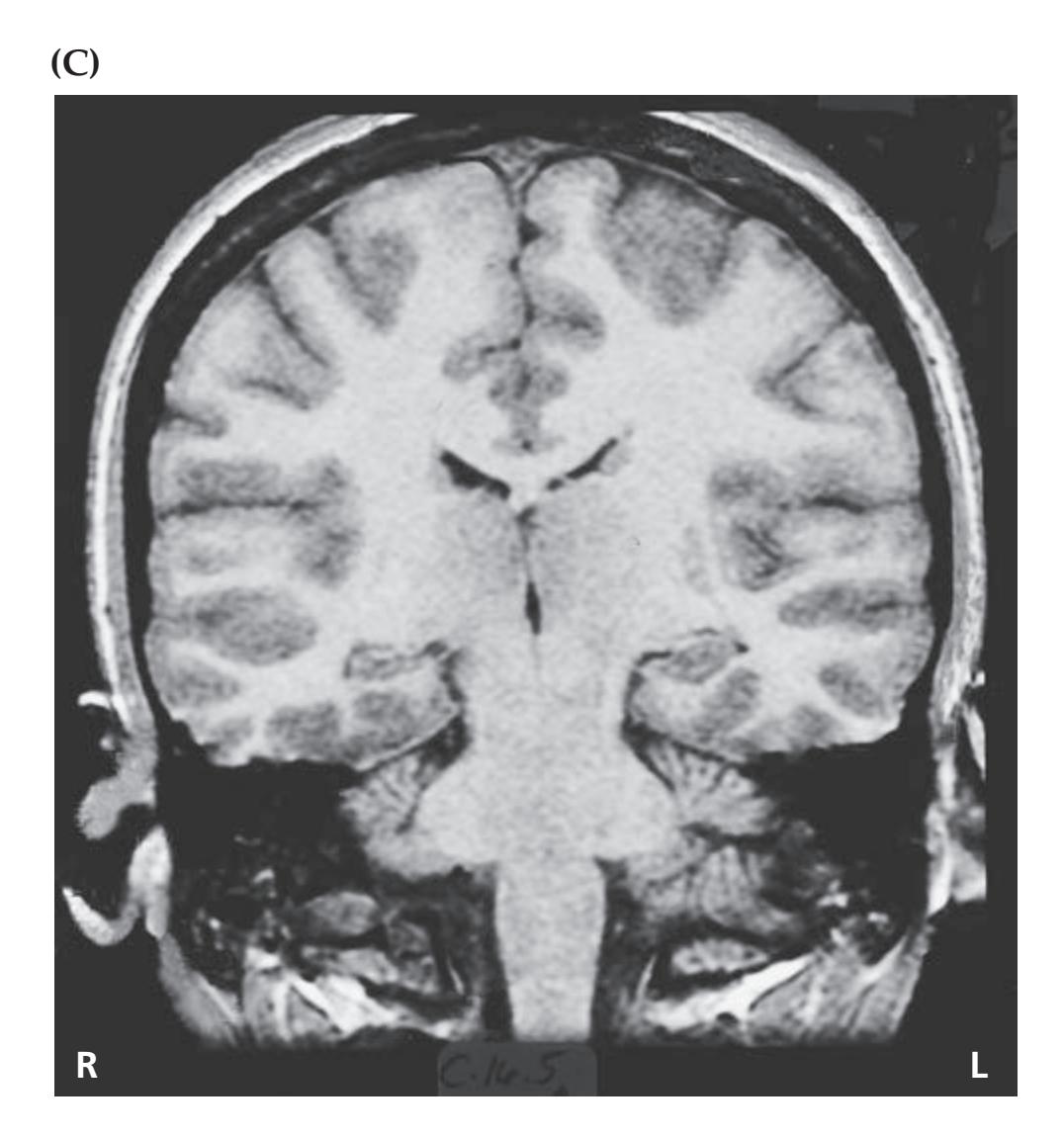

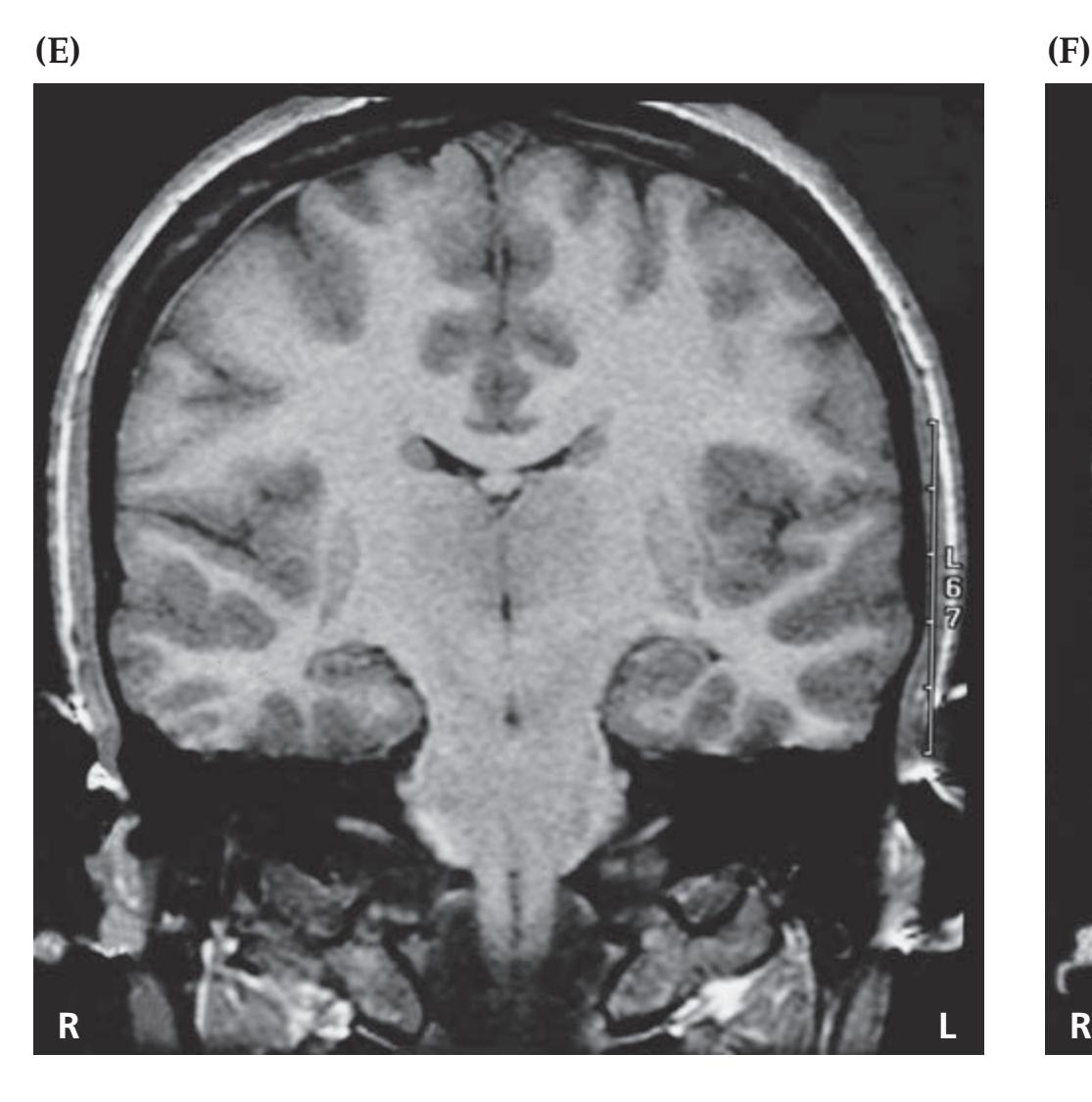

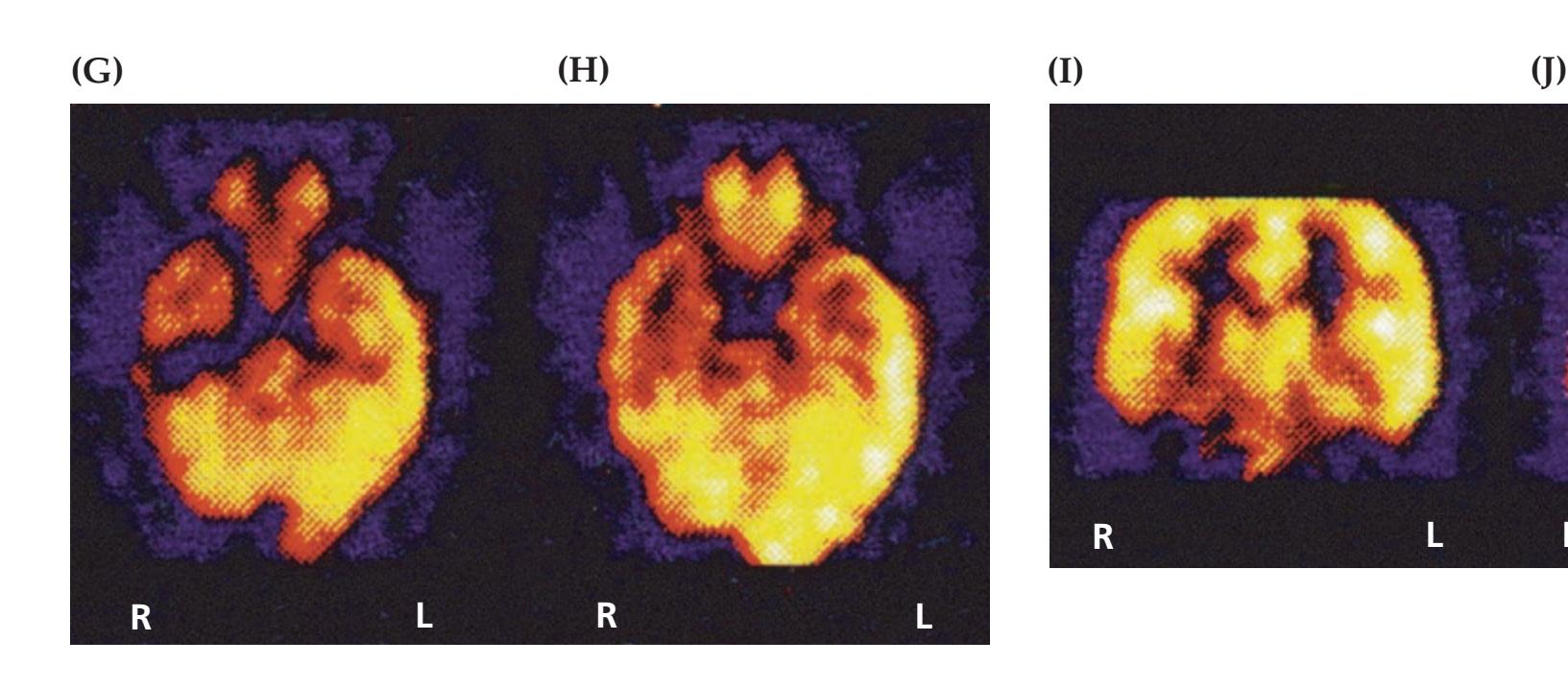

## Chapter 18 *Limbic System: Homeostasis, Olfaction, Memory, and Emotion 823*

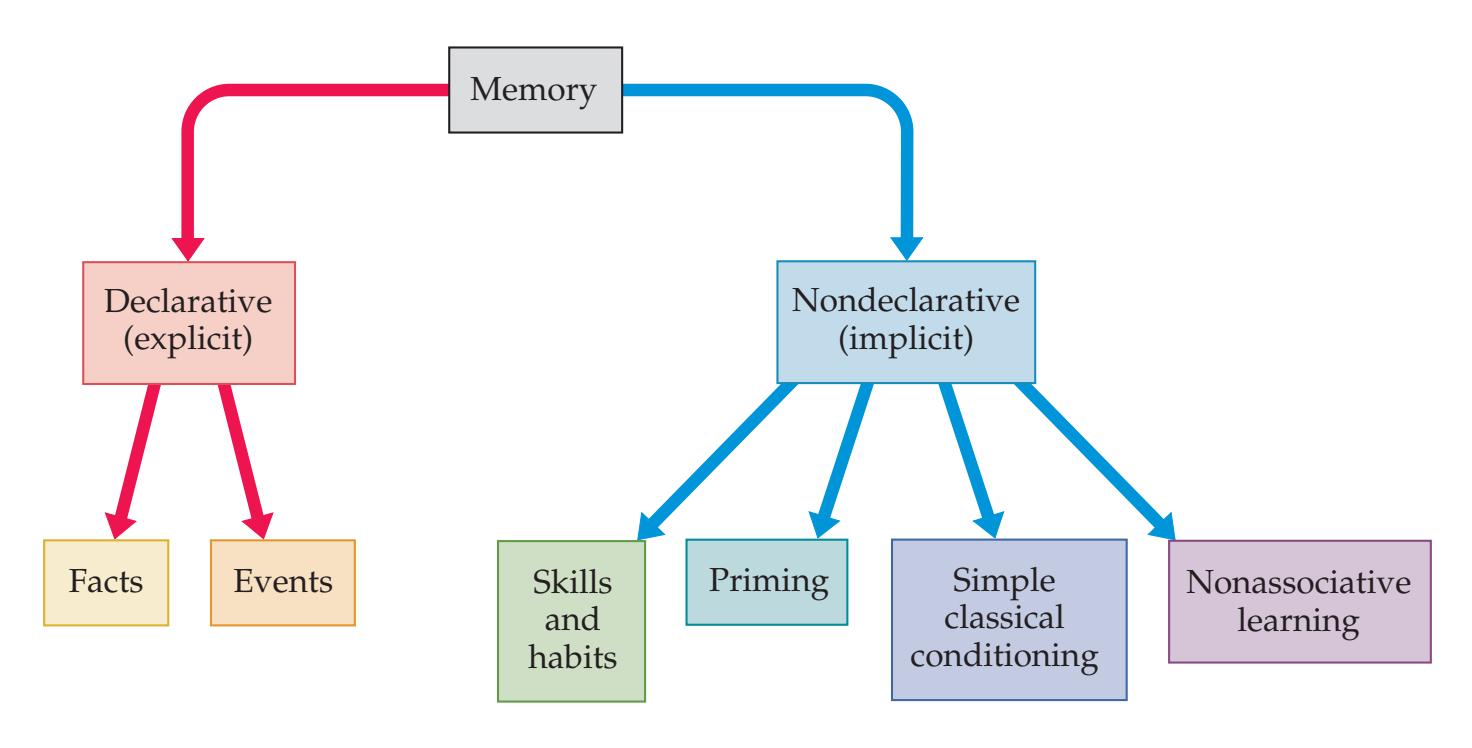

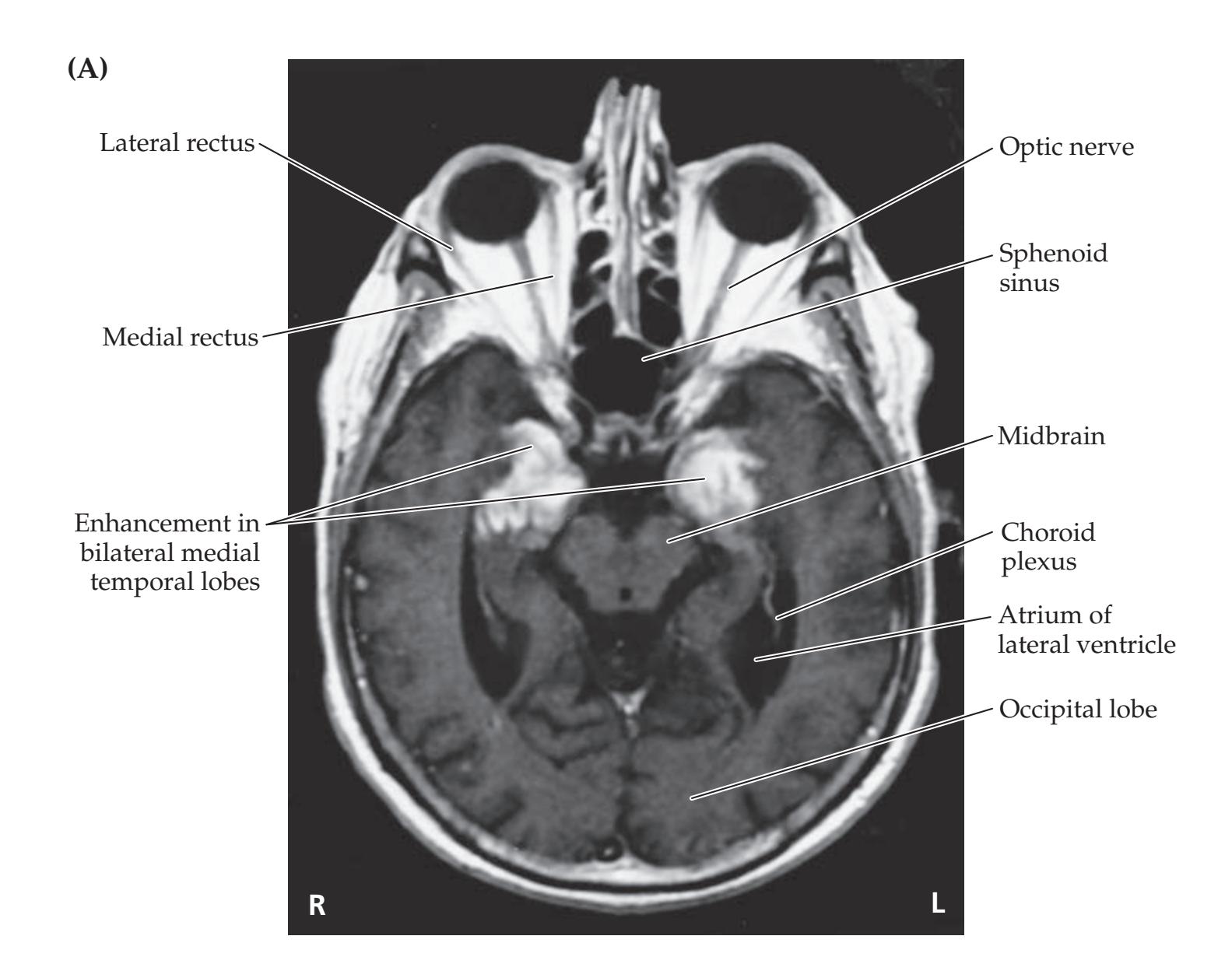

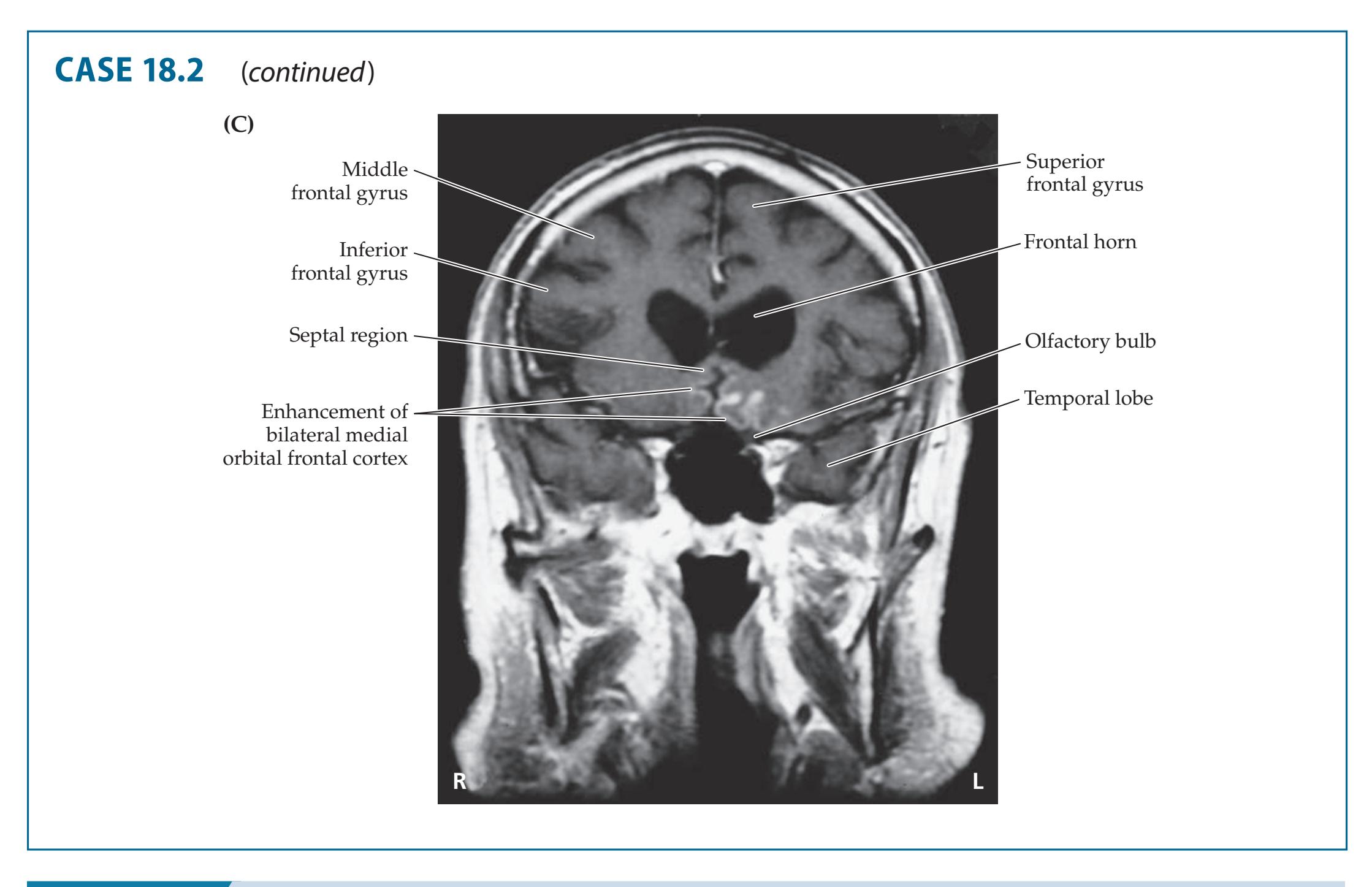

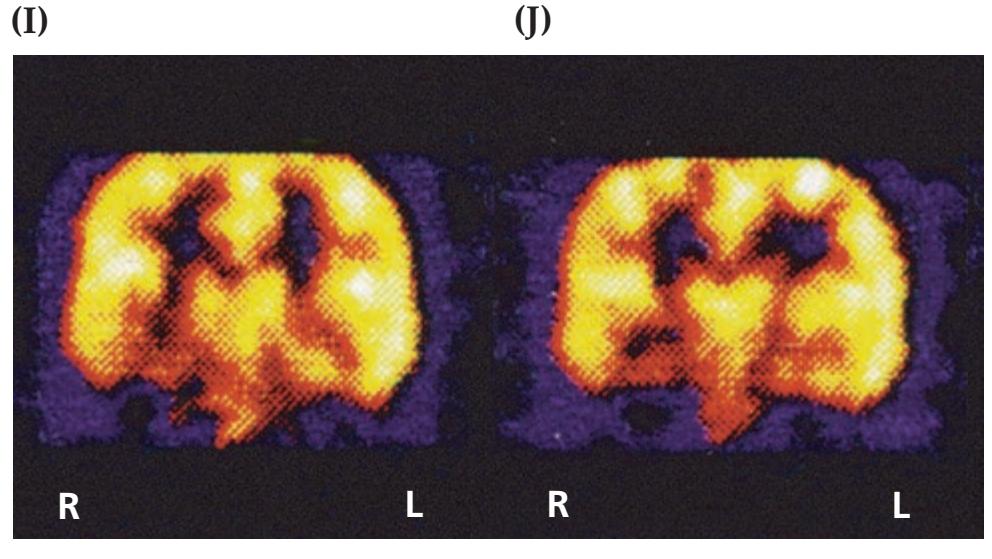

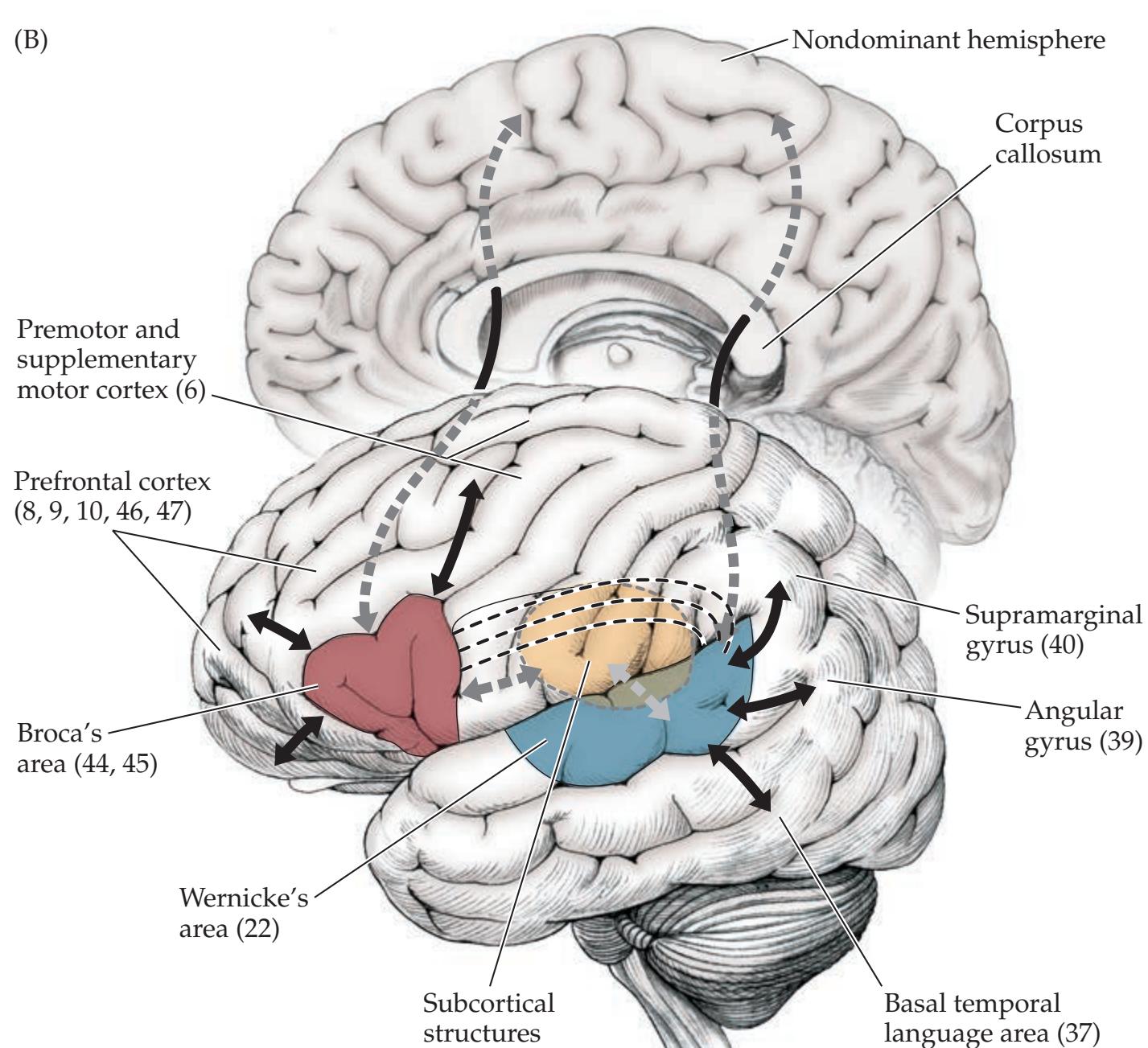

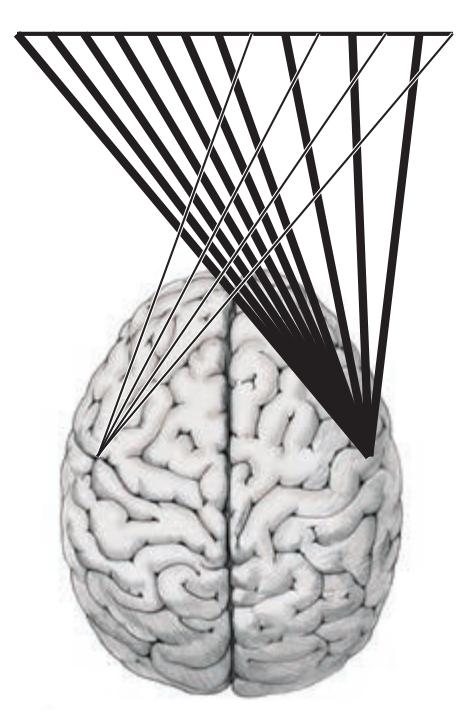

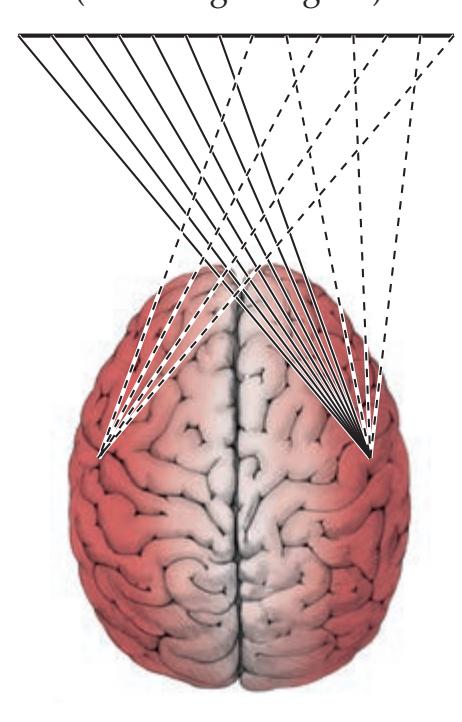

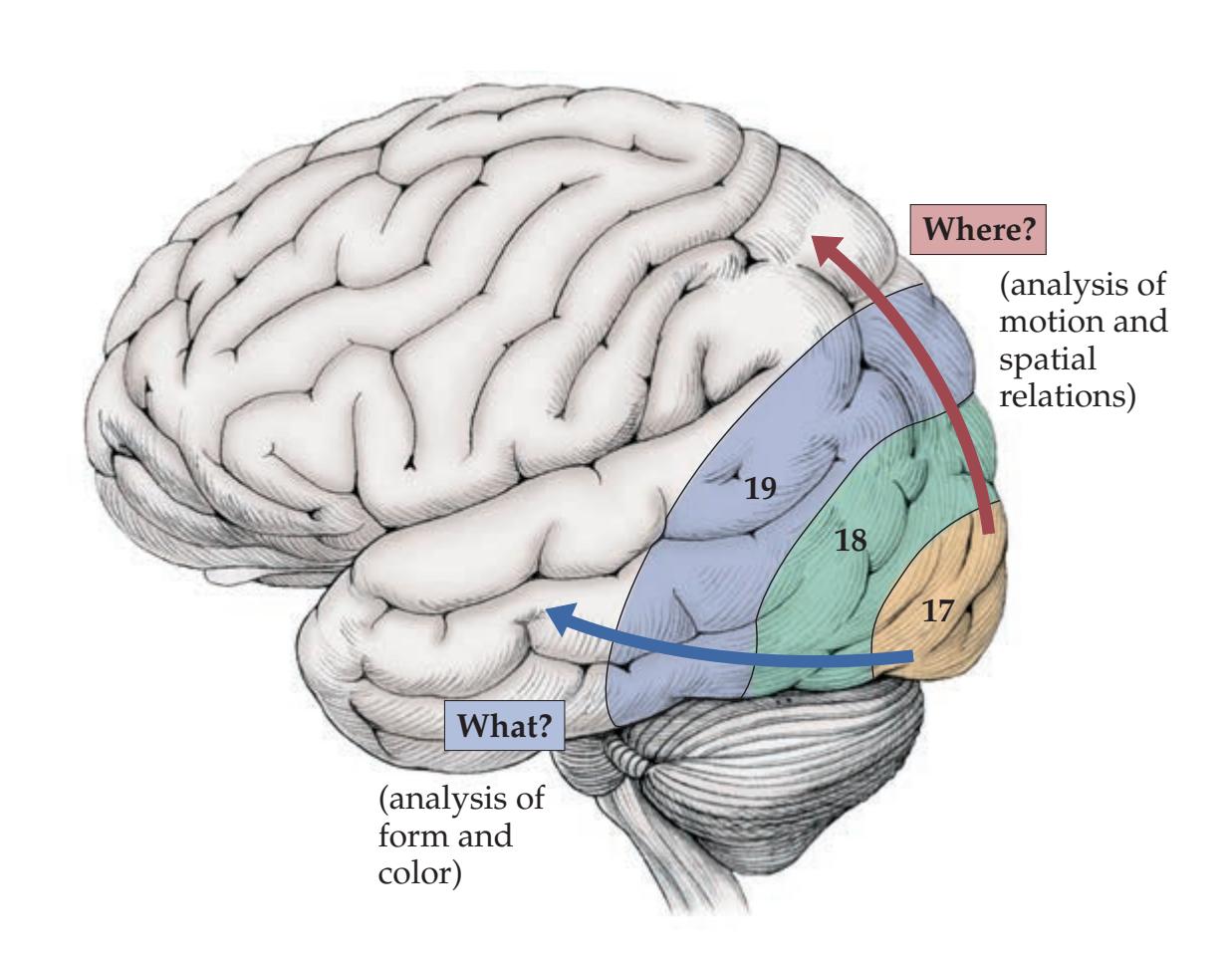

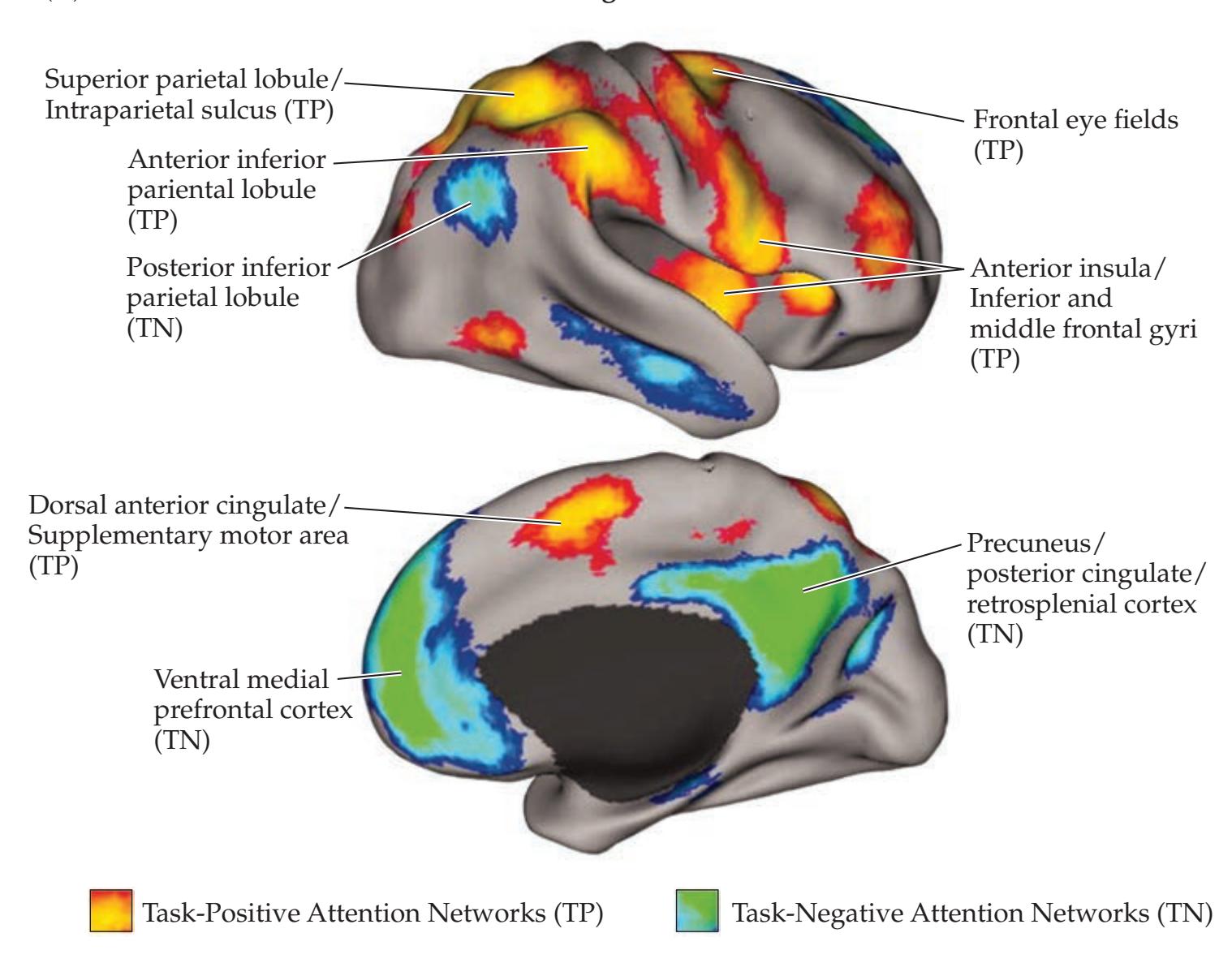

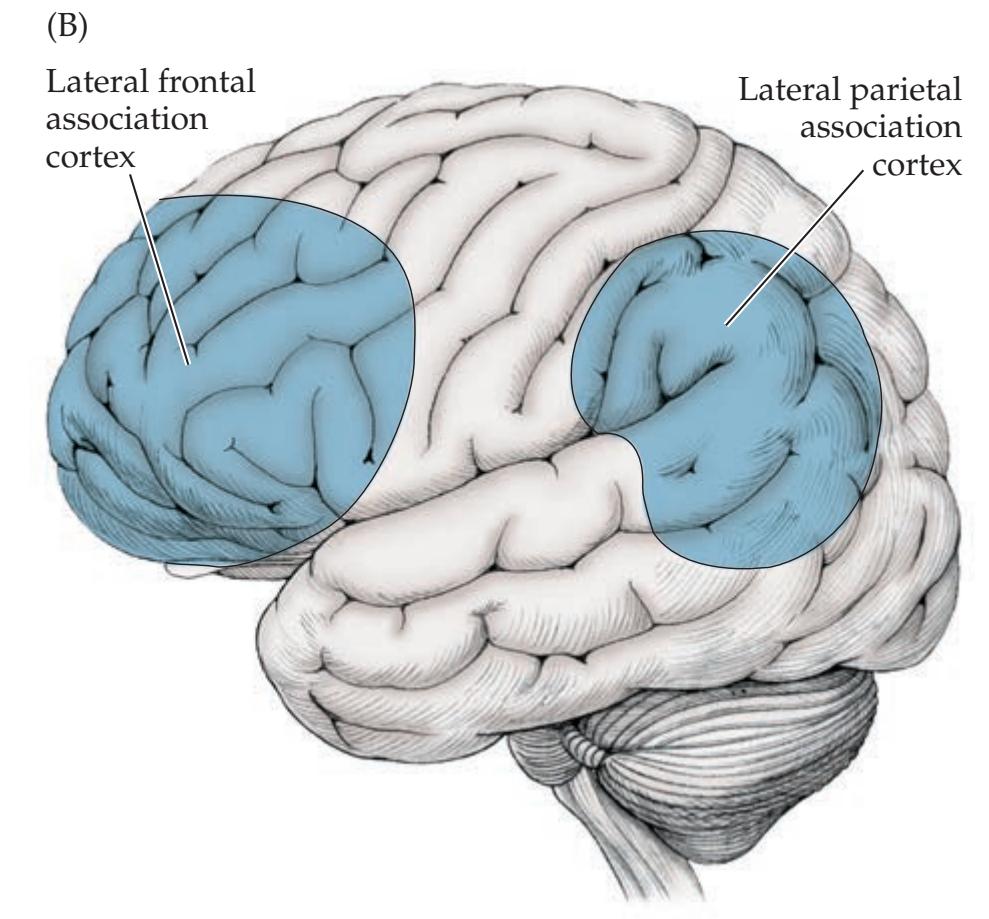

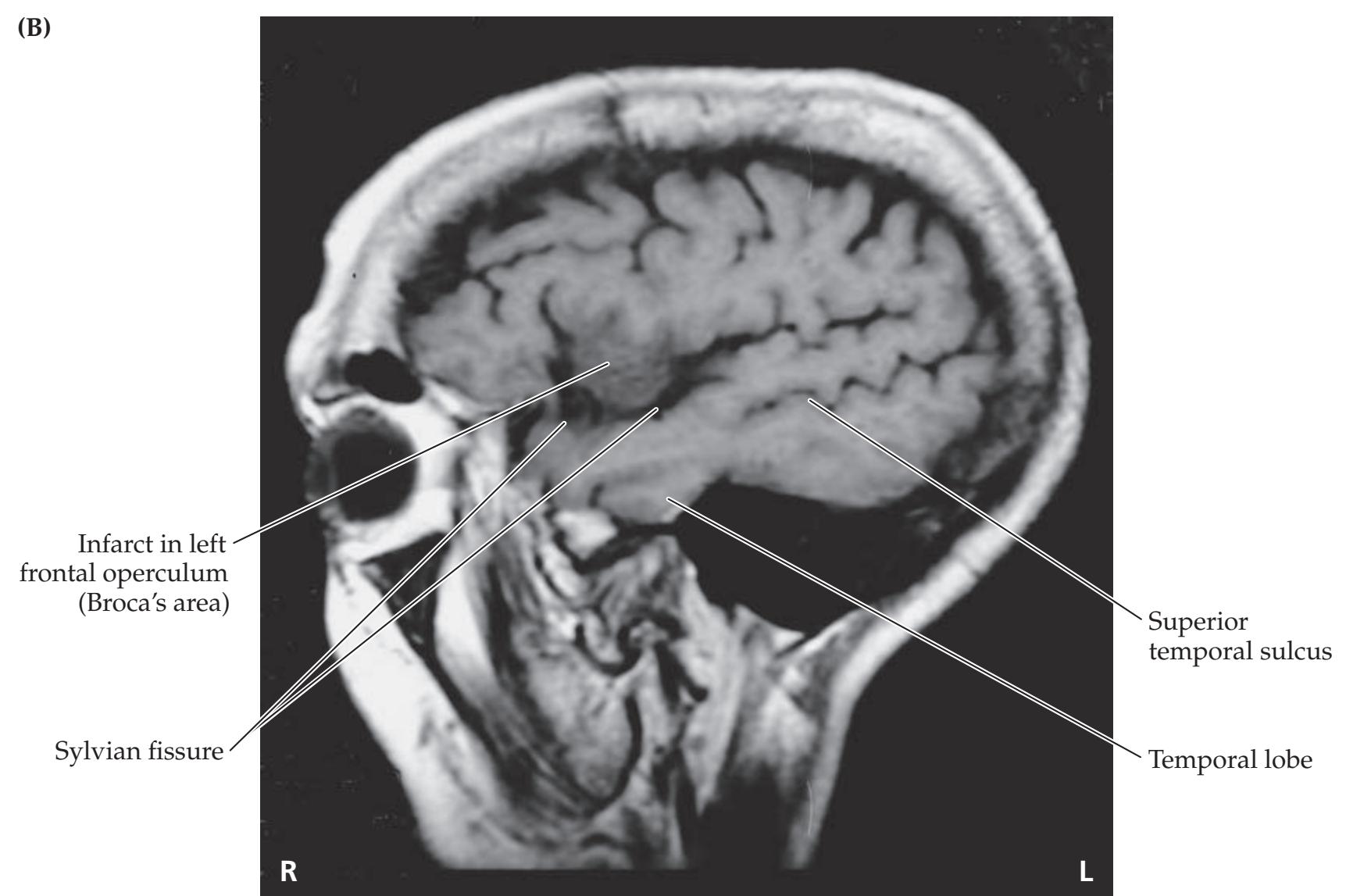

### **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 824 Overview of Limbic Structures 825 Olfactory System 831 Hippocampal Formation and Other Memory-Related Structures 833 KCC 18.1** Memory Function and Memory Disorders 842 **The Amygdala: Emotions, Drives, and Other Functions 849 Other Limbic Pathways 852 KCC 18.2** Seizures and Epilepsy 852 **KCC 18.3** Anatomical and Neuropharmacological Basis of Psychiatric Disorders 862 **CLINICAL CASES 865 18.1** Sudden Memory Loss after a Mild Head Injury 865 **18.2** Progressive Severe Memory Loss, with Mild Confabulation 866 **18.3** Memory Loss, Double Vision, and Incoordination 869 **18.4** Episodes of Panic, Olfactory Hallucinations, and Loss of Awareness 871 **18.5** Episodes of Staring, Lip Smacking, and Unilateral Semipurposeful Movements 875 **Additional Cases 877 BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 881 References 883** Chapter 19 *Higher-Order Cerebral Function 887* **ANATOMICAL AND CLINICAL REVIEW 888 KCC 19.1** The Mental Status Exam 888 **Unimodal and Heteromodal Association Cortex 889 Principles of Cerebral Localization and Lateralization 891 The Dominant Hemisphere: Language Processing and Related Functions 893 KCC 19.2** Differential Diagnosis of Language Disorders 896 **KCC 19.3** Bedside Language Exam 897 **KCC 19.4** Broca's Aphasia 897 **KCC 19.5** Wernicke's Aphasia 899 **KCC 19.6** Simplified Aphasia Classification Scheme 900 **KCC 19.7** Other Syndromes Related to Aphasia 902 **KCC 19.8** Disconnection Syndromes 905 **The Nondominant Hemisphere: Spatial Processing and Lateralized Attention 906 KCC 19.9** Hemineglect Syndrome 908 **KCC 19.10** Other Clinical Features of Nondominant Hemisphere Lesions 913 **The Frontal Lobes: Anatomy and Functions of an Enigmatic Brain Region 914 KCC 19.11** Frontal Lobe Disorders 916 **Visual Association Cortex: Higher-Order Visual Processing 921 The Consciousness System Revisited: Anatomy of Attention 926 KCC 19.14** Attentional Disorders 930 **KCC 19.15** Delirium and Other Acute Mental Status Disorders 932 **KCC 19.16** Dementia and Other Chronic Mental Status Disorders 934 **Brain Mechanisms of Conscious Awareness: Detect, Pulse, Switch, and Wave Model 942 CLINICAL CASES 948 19.1** Acute Severe Aphasia, with Improvement 948 **19.2** Nonsensical Speech 950 **19.3** Aphasia with Preserved Repetition 951 **19.4** Impaired Repetition 953 **19.5** Inability to Read, with Preserved Writing Skills 956 **19.6** Left Hemineglect 961 **19.7** Abulia 963 **19.8** Blindness without Awareness of Deficit 967 **19.9** Sudden Inability to Recognize Faces 971 **19.10** Musical Hallucinations 972 **19.11** Progressive Dementia, Beginning with Memory Problems 973 **Additional Cases 975 BRIEF ANATOMICAL STUDY GUIDE 977 References 980**

**KCC 19.12** Disorders of Higher-Order Visual Processing 922

**KCC 19.13** Auditory Hallucinations 925

Contents **xv**

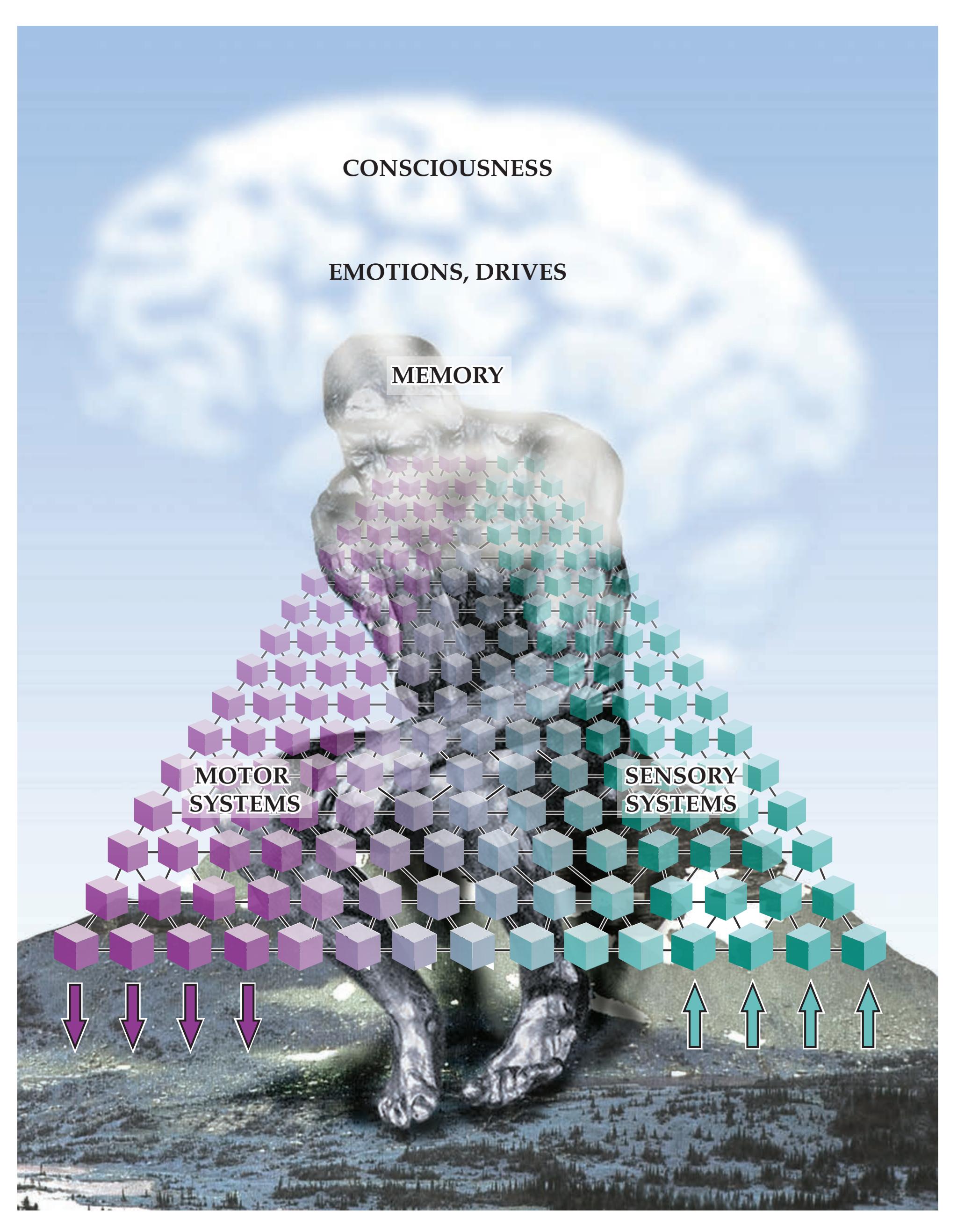

**Epilogue: A Simple Working Model of the Mind 987**

**Case Index 991**

**Subject Index 997**

# *Preface*

Neuroanatomy is a living, dynamic field that can bring both intellectual delight and aesthetic pleasure to students at all levels. However, by nature, it is also an exceedingly detailed subject, and herein lies the tragic pitfall of all too many neuroanatomy courses. Crushing amounts of memorization are often required of students of neuroanatomy, leaving them little time to step back and gain an appreciation of the structural and functional beauty of the nervous system and its relevance to clinical practice.

This book has a different point of view: instead of making the mastery of anatomical details the main goal and then searching for applications of this knowledge, actual clinical cases are used as both a teaching instrument and a motivating force to encourage students to delve into further study of normal anatomy and function. Through this approach, structural details take on immediate relevance as they are being learned. In addition, each clinical case is an ideal way to integrate knowledge of disparate functional systems, since a single lesion may affect several different neural structures and pathways.

Over 100 clinical cases, accompanied by neuroradiological images, are presented in this text, and I am grateful to many neurologists, neurosurgeons, and neuroradiologists at the Columbia, Harvard, and Yale medical schools for helping me to amass enough material to present clinically relevant discussions of the entire nervous system. I have used this book's diagnostic method to teach neuroanatomy at these medical schools, and both students and faculty greeted the innovation enthusiastically. Through publication of *Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases* I hope that students and faculty at many additional institutions will find this to be an enjoyable and effective way to learn neuroanatomy and its real-life applications.

## **Acknowledgments for First Edition**

First and foremost, I must thank my wife Michelle, and our children Eva and Jesse, for their enthusiasm and support throughout the writing and publication of this book.

This project has spanned a number of years, and stints at several academic centers, so there is a formidable list of people whom I must thank for their important contributions. This book was conceived while I was teaching neuroanatomy as an M.D., Ph.D. student at Columbia Medical School, where I was inspired by my teachers Eric Kandel, Jack Martin, and Steven Siegelbaum. They have remained invaluable sources of inspiration and advice ever since. I would also like to thank the following individuals who served as mentors, benefactors, or role models during my training as a neurologist and neuroscientist: Raymond D. Adams, Bernard Cohen, C. Miller Fisher, Jack Haimovic, Walter Koroshetz, Terry Krulwich, Elan Louis, Stephan Mayer, David McCormick, Thomas McMahon, Timothy Pedley, Pasko Rakic, Susan Spencer, Dennis Spencer, Stephen Waxman, Anne Young, and George Zubal. I would also like to offer special thanks to those who were my closest colleagues and friends during my neurology residency: Jang-Ho Cha, Mitchell Preface **xvii**

Elkind, Martha Herbert, David Jacoby, Michael Lin, Guy Rordorff, Diana Rosas, and Gerald So.

The focus and main strength of this book is its clinical cases. Therefore, I am very grateful to the many colleagues who suggested the clinical cases used in this book: Robert Ackerman, Claudia Baldassano, Tracy Batchelor, Flint Beal, Carsten Bonneman, Lawrence Borges, Robert Brown, Jeffrey Bruce, Brad Buchbinder, Ferdinando Buonanno, William Butler, Steve Cannon, David Caplan, Robert Carter, Verne Caviness, Jang-Ho Cha, Paul Chapman, Chinfei Chen, Keith Chiappa, In Sup Choi, Andrew Cole, Douglas Cole, G. Rees Cosgrove, Steven Cramer, Didier Cros, Merit Cudkowicz, Kenneth Davis, Rajiv Desai, Elizabeth Dooling, Brad Duckrow, Mitchell Elkind, Emad Eskandar, Stephen Fink, Seth Finkelstein, Alice Flaherty, Robert Friedlander, David Frim, Zoher Ghogawala, Michael Goldrich, Jonathan Goldstein, R. Gilberto Gonzalez, Kimberly Goslin, Steven Greenberg, John Growdon, Andrea Halliday, E. Tessa Hedley-Whyte, Martha Herbert, Daniel Hoch, Fred Hochberg, J. Maurice Hourihane, Brad Hyman, Michael Irizarry, David Jacoby, William Johnson, Raymond Kelleher, Philip Kistler, Walter Koroshetz, Sandra Kostyk, Kalpathy Krishnamoorthy, James Lehrich, Simmons Lessell, Michael Lev, Susan Levy, Michael Lin, Elan Louis, David Louis, Jean Lud-Cadet, David Margolin, Richard Mattson, Stephan Mayer, James Miller, Shawn Murphy, Brad Navia, Steven Novella, Edward Novotny, Christopher Ogilvy, Robert Ojemann, Michael Panzara, Dante Pappano, Stephen Parker, Marie Pasinski, John Penney, Bruce Price, Peter Riskind, Guy Rordorff, Diana Rosas, Tally Sagie, Pamela Schaefer, Jeremy Schmahmann, Lee Schwamm, Michael Schwarzschild, Saad Shafqat, Barbara Shapiro, Aneesh Singhal, Michael Sisti, Gerald So, Robert Solomon, Marcio Sotero, Dennis Spencer, Susan Spencer, John Stakes, Marion Stein, Divya Subramanian-Khurana, Brooke Swearingen, Max Takeoka, Thomas Tatemichi, Fran Testa, James Thompson, Mark Tramo, Jean Paul Vonsattel, Shirley Wray, Anne Young, and Nicholas Zervas.

I am deeply indebted to the many individuals who provided critical reviews of one or more chapters, greatly enhancing the accuracy and clarity of the material in this book: Raymond D. Adams, Joshua Auerbach, William W. Blessing, Laura Blumenfeld, William Boonn, Lawrence Borges, Michelle Brody, Richard Bronen, Joshua Brumberg, Thomas N. Byrne, Mark Cabelin, Jang-Ho Cha, Jaehyuk Choi, Charles Conrad, Rees Cosgrove, Merit Cudkowicz, Mitchell Elkind, C. M. Fisher, David Frim, Darren R. Gitelman, Jonathan Goldstein, Gil Gonzalez, Charles Greer, Stephan Heckers, Tamas Horvath, Gregory Huth, Michael Irizarry, Joshua P. Klein, Igor Koralnick, John Krakauer, Matthew Kroh, Robert H. LaMotte, John Langfitt, Steven B. Leder, Elliot Lerner, Grant Liu, Andres Martin, John H. Martin, Ian McDonald, Lyle Mitzner, Hrachya Nersesyan, Andrew Norden, Robert Ojemann, Stephen Parker, Huned Patwa, Howard Pomeranz, Bruce Price, Anna Roe, David Ross, Jeremy Schmahmann, Mark Schwartz, Ted Schwartz, Michael Schwarzschild, Barbara Shapiro, Scott Small, Arien Smith, Adam Sorscher, Susan Spencer, Stephen M. Strittmatter, Larry Squire, Mircea Steriade, Ethan Taub, Timothy Vollmer, and Steven U. Walkley. I express my gratitude for their helpful suggestions, but accept full responsibility for any errors in this text.

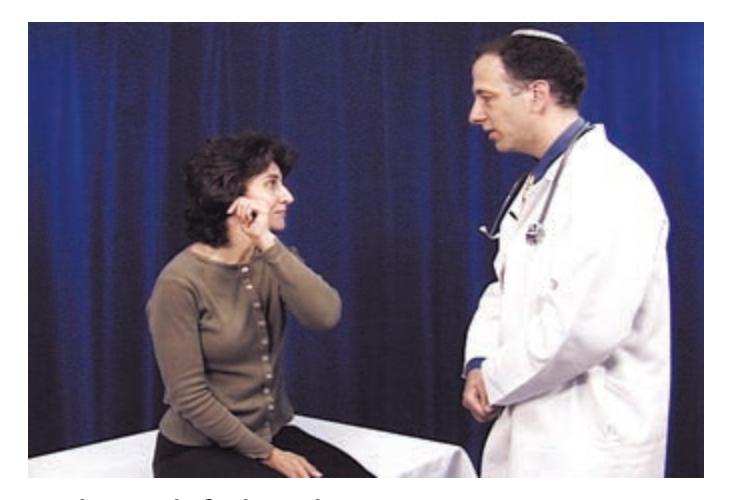

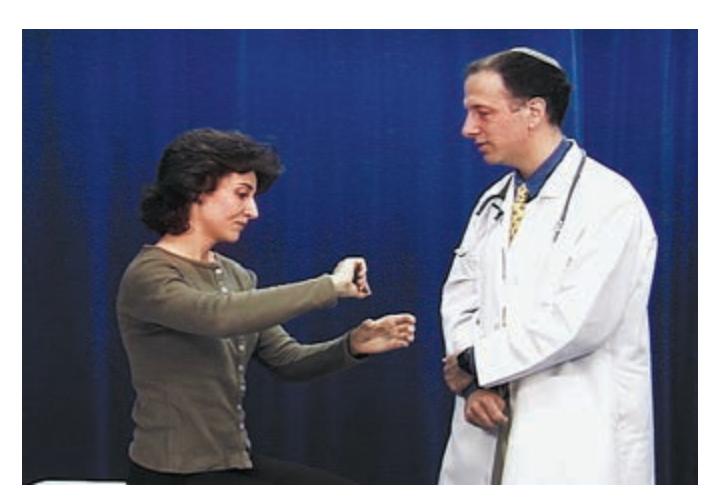

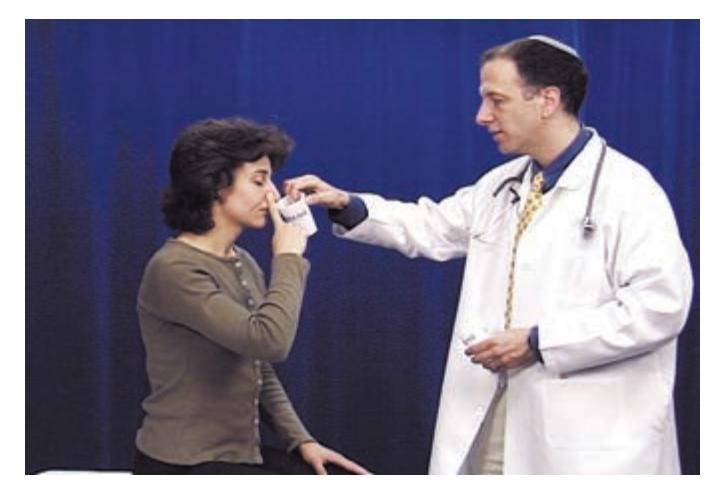

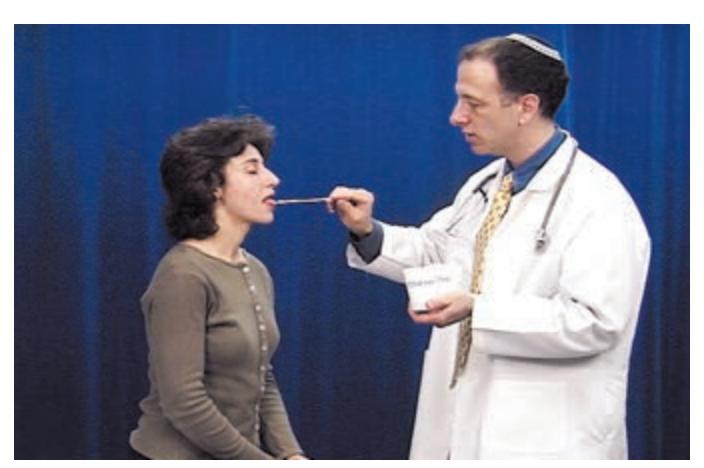

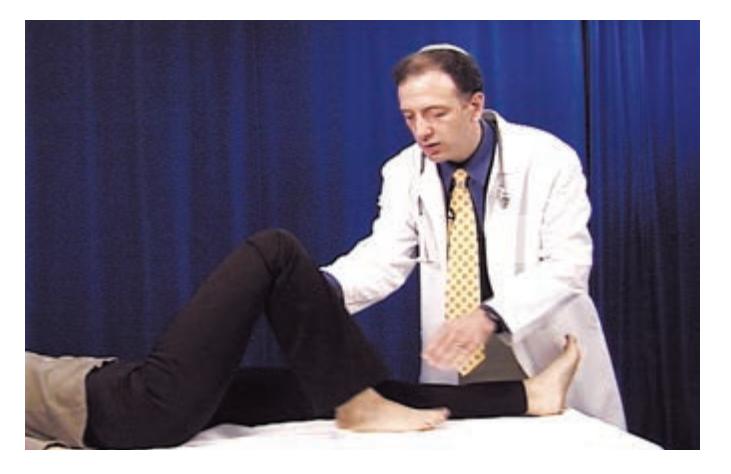

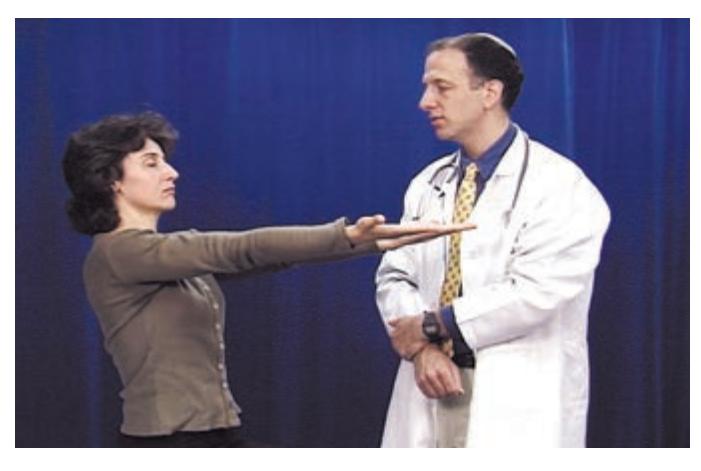

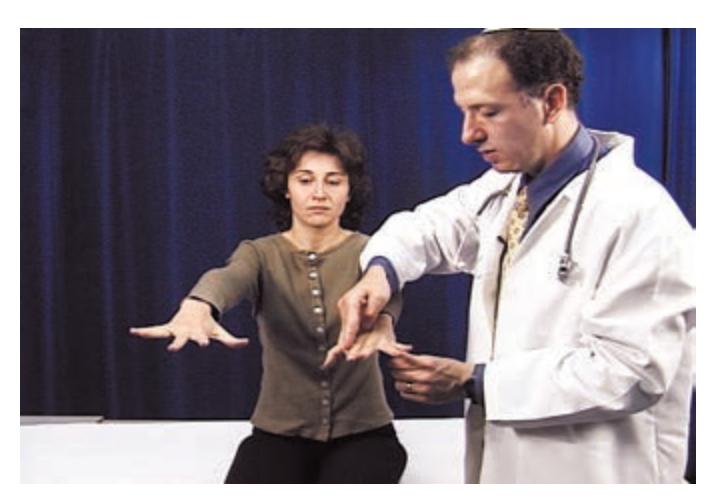

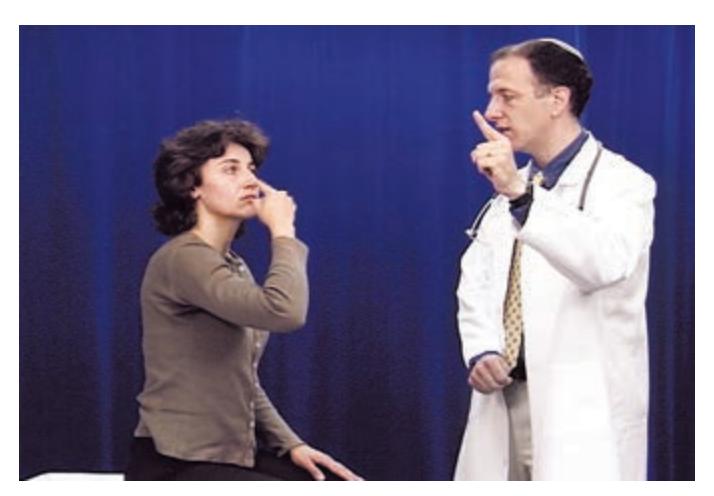

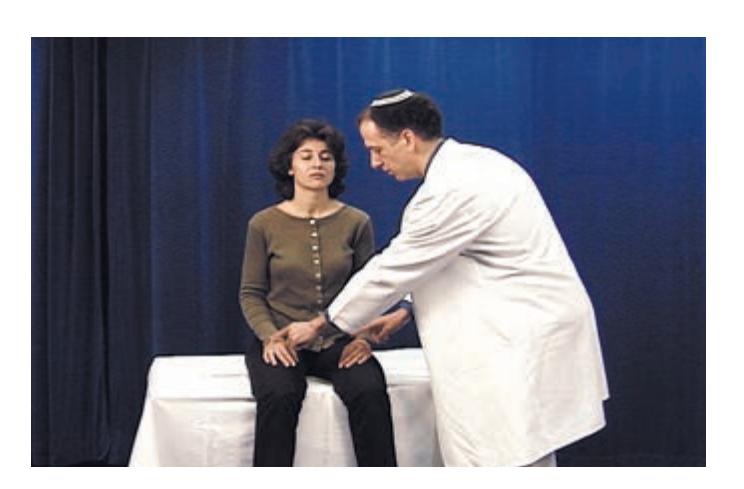

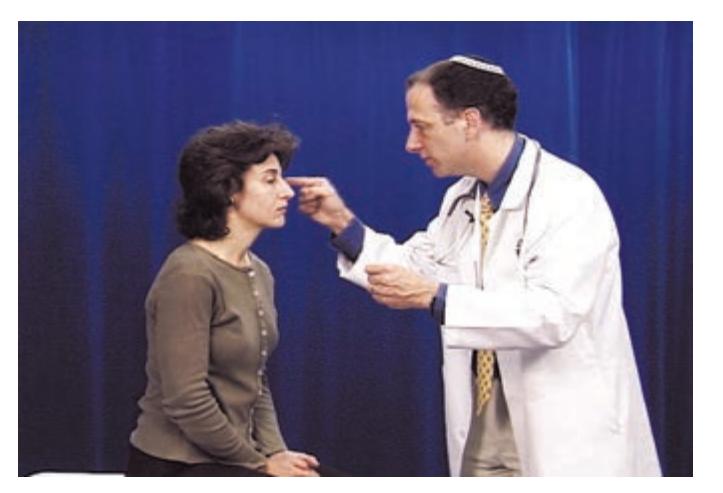

Marty Wonsiewicz, John Dolan, Greg Huth, John Butler, and Amanda Suver were helpful in the early stages of editorial development of this book. Michael Schlosser and Tasha Tanhehco helped gather the references, and Jason Freeman and Susan Vanderhill helped obtain copyright permissions. Wendy Beck and BlackSheep Marketing designed and implemented the neuroexam. com website. The video segments for **neuroexam.com** and *The NeuroExam Video* were filmed by Douglas Forbush and Patrick Leone at Yale, and edited by Evan Jones of RBY Video. Milena Pavlova provided helpful suggestions, and played the role of the patient.

**xviii** Preface

Finally, I thank the entire staff at Sinauer Associates for their tremendously helpful collaboration in all stages of producing this book. I have enjoyed working with, and am especially grateful to, Andrew D. Sinauer, Peter Farley, Kerry Falvey, Christopher Small, and Jefferson Johnson, but I extend my deep appreciation to all other members of the Sinauer staff as well. It is a pleasure to work with people who truly care about creating a fine book.

## **Additional Acknowledgments for Second Edition**

My family again comes first in my acknowledgments, as they stood closest by me through the long process of revising and updating this book. I thank Michelle for her advice and support, and our children Eva, Jesse, and Lev for their enthusiasm and for always bringing a smile to my face. Also, none of this would have been possible without my parents who continue to be a source of inspiration. My sister, "the real writer in the family," and many other family members and close, lifelong friends complete the list of those most precious.

In addition to those listed in the Acknowledgments for the First Edition, I would also like to thank the following outstanding colleagues for their suggested cases or critical chapter reviews: Nazem Atassi, Joachim Baehring, Margaret Bia, William Blessing, Richard Bronen, Franklin Brown, Joshua Brumberg, Gordon Buchanan, Ketan Bulsara, Louis Caplan, Michael Carrithers, Jang-Ho Cha, Michael Crair, Merit Cudkowicz, Robin De Graaf, Daniel DiCapua, Mitchell Elkind, Carl Faingold, Susan Forster, Robert Fulbright, Karen Furie, Glenn Giesler, Darren Gitelman, Charles Greer, Stephen Grill, Noam Harel, Joshua Hasbani, Elizabeth Holt, Bahman Jabbari, Jason Klenoff, Igor Koralnick, Randy Kulesza, Robert LaMotte, Steven Leder, Ben Legesse, Robert Lesser, Albert Lo, Grant Lui, Steve Mackey, Andres Martin, Graeme Mason, Andrew Norden, Haakon Nygaard, Kyeong Han Park, Stephen Parker, Huned Patwa, Howard Pomeranz, Stephane Poulin, Sashank Prasad, Bruce Price, Diana Richardson, George Richerson, Anna Roe, David Russell, Robert Sachdev, Gerard Sanacora, Joseph Schindler, Michael Schwartz, Theodore Schwartz, Alan Segal, Nutan Sharma, Gordon Shepherd, Scott Small, Adam Sorscher, Joshua Steinerman, Daryl Story, Ethan Taub, Kenneth Vives, Darren Volpe, Jonathan Waitman, Howard Weiner, Norman Werdiger, Michael Westerveld, and Shirley Wray.

Medical students contributed in an important way to this edition by helping me find new cases and images. Wenya Linda Bi, Alexander Park, April Levin, Matthew Vestal, Kathryn Giblin, Alexandra Miller, Joshua Motelow, and Amy Forrestel spent many early morning hours reviewing case materials for this book. Dragonfly Media Group contributed to art revisions, Picture Mosaics created the cover mosaic, Jean Zimmer provided copy editing, and Nathan Danielson helped draft the concept for the cover design.

Once again, I am very grateful to the entire staff of Sinauer Associates for their outstanding attention to high-quality publishing, and for their collaboration in all aspects of producing this book. I have enjoyed working on the Second Edition with Sydney Carroll, Graig Donini, Joan Gemme, Christopher Small, Jason Dirks, Linda VandenDolder, Marie Scavotto, Dean Scudder, and Andrew D. Sinauer. Having worked on two editions with Sinauer, I have an ever-deepening appreciation of the success of this group in producing excellent books.

## **Additional Acknowledgments for Third Edition**

As our journey continues, I again thank my family first for all their love, support, and inspiration. Sheltering in our home these past months with Michelle, my wonderful life partner, and our now adult or nearly adult children Eva, Preface **xix**

Jesse, and Lev has been comforting in the face of challenging times in the world. I am also grateful to my dear parents, siblings and significant others Norma Grill, David Blumenfeld, Laura Blumenfeld, Baruch Weiss, Frances Blumenfeld, Bernard Grill (a'h), Leonard Kresch, Marsha Brody, Peter Brody, Adrienne Alexander, Michael Alexander, Rachel Brody, Michael Lustig, Barak Pearlmutter, Helena Smigoc, Nili Pearlmutter, Todd Bearson, Stephen Grill and Ellen Grill. Lifelong friends I won't enumerate by name complete the list of those most precious through the years.

In addition to those listed in the Acknowledgments for the First and Second Editions, I would like to thank the following colleagues for their excellent and highly informative chapter reviews: Hamada Altalib, Hardik P Amin, Nigel Bamford, Christopher Benjamin, Hilary Blumberg, Kenneth Blumenfeld, Richard Bronen, Joshua Brumberg, Gordon Buchanan, Zachary Corbin, Robin De Graaf, Kunal Desai, Jeffrey Dewey, George Dragoi, Mitchell Elkind, Hilary Fazzone, Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh, Adeniyi Fisayo, Robert Fulbright, Emily Gilmore, Darren R. Gitelman, Lauren Gluck, Christopher Gottschalk, Elena Gracheva, David Greer, Stephen Grill, Joshua Hasbani, David Heeger, Firas Kaddouh, Benison Keung, Babar Khokhar, Joshua Klein, Ninani Kombo, Igor Koralnik, Beth B. Krippendorf, Randy J. Kulesza, Alex Kwan, Maxwell Laurans, Jonathan Levitt, Steve Mackey, Graeme Mason, Matthew McGinley, Ana-Claire L. Meyer, Mario Monto, Elliot Morse, Maitreyi Murthy, Kumar Narayanan, Haakon Nygaard, Amar Patel, Kenneth Perrine, Patricia Peter, David Pitt, Howard Pomeranz, Amanda Redfern, George Richerson, Liana Rosenthal, Jarrett Rushmore, Arash Salardini, Lauren Sansing, Shobhit Singla, Joshua Steinerman, Jaideep S. Talwalkar, Ethan Taub, Sule Tinaz, Bertrand Tseng, Nick Turk-Browne, Susan Vandermorris, Phyllis E. Weingarten Kann, Norman Werdiger, and Michael Westerveld.

I am grateful to the following medical students who met with me weekly early in the morning to review new clinical cases for this edition: Irina Shklyar, Jose Gonzalez, Abhijeet Gummadavelli, Leisel Martin, Nathan Tu, Hilary Hanbing Wang, Mark Youngblood, Ningcheng (Peter) Li, Benjamin Lerner, Adam Kundishora, Hiam Naiditch, Rahiwa Gebre, John Andrews, Eric Chen, Prince Antwi, Neal Dolan, Swetha Dravida, and Natnael Doilicho. Swetha Dravida and Natnael Doilicho also contributed to updating the References. Art revisions were provided by the Dragonfly Media Group, Wendy Walker performed copy editing, and Thundercloud Consulting assisted with digital production of the e-book.

With the Third Edition, the excellent publisher Sinauer Associates has now become an imprint of another excellent publisher, Oxford University Press. Shortly after this transition, Sydney Carroll, who had worked with me on 1e and 2e, helped me see the importance of the Third Edition. I am very deeply grateful to all of the outstanding professionals at Sinauer Associates/Oxford University Press who have made working and collaborating on this new edition a true pleasure, including Jessica Fiorillo, Stephanie Nisbet, Karissa Venne, Jason Dirks, Joan Gemme, Beth Roberge, Michele Beckta, Linda VandenDolder, Lauren Cahillane, Morgan Delahunt, and Kathaleen Emerson. This incredible team demonstrates the value of true excellence in book publishing.

# *How to Use This Book*

The goal of this book is to provide a treatment of neuroanatomy that is comprehensive, yet enables students to focus on the most important "take-home messages" for each topic. This goal is motivated by the recognition that, while access to detailed information is often useful in mastering neuroanatomy, certain selected pieces of information carry the most clinical relevance, or are most important for exam review.

## **General Outline**

The first four chapters of the book contain introductory material that will be especially useful to students who have little previous clinical background. Chapter 1 is an introduction to the standard format commonly used for presenting clinical cases, including an outline of the medical history, physical examination, neuroanatomical localization, and differential diagnosis. Chapter 2 is a brief overview of neuroanatomy which includes definitions and descriptions of basic structures that will be studied in greater detail in later chapters. Chapter 3 builds on this knowledge by describing the neurologic examination. It includes a summary of the structures and pathways tested in each part of the exam, which is essential for localizing the lesions presented in the clinical cases throughout the remainder of the book. Much of the material in this chapter is also covered on the neuroexam.com website described below, which provides video demonstrations for each part of the exam. For readers who are unfamiliar with neuroimaging techniques, Chapter 4 contains a concise introduction to CT, MRI, and other imaging methods. This chapter also includes a Neuroradiological Atlas showing normal CT, MRI, and angiographic images of the brain. Chapters 5–19 cover the major neuroanatomical systems and present relevant clinical cases.

## **Chapters 5–19**

Chapters 5–19 have a common structure. An "Anatomical and Clinical Review" at the beginning of the chapters presents relevant neuroanatomical structures and pathways, and generously sized, carefully labeled color illustrations are used to vividly depict spatial relationships. The first part of each chapter also includes numbered sections called "Key Clinical Concept," or "KCC," which cover common disorders of the system being discussed.

**CLINICAL CASES** The second part of each chapter is a "Clinical Cases" section that describes patients seen by the author and colleagues, each presented in a numbered color box. Full-length cases include complete findings from the neurologic examination, while "Minicases" have a briefer format. Each case begins with a narrative of how the patient's symptoms developed and what deficits were found on neurologic examination. For example, one How to Use This Book **xxi**

patient in Chapter 10 suddenly developed weakness in the right hand and lost the ability to speak. Another, in Chapter 14, experienced double vision and lapsed into a coma. Important symptoms and signs are indicated in boldface type. The reader is then challenged through a series of questions to deduce the neuroanatomical location of the patient's lesion and the eventual diagnosis.

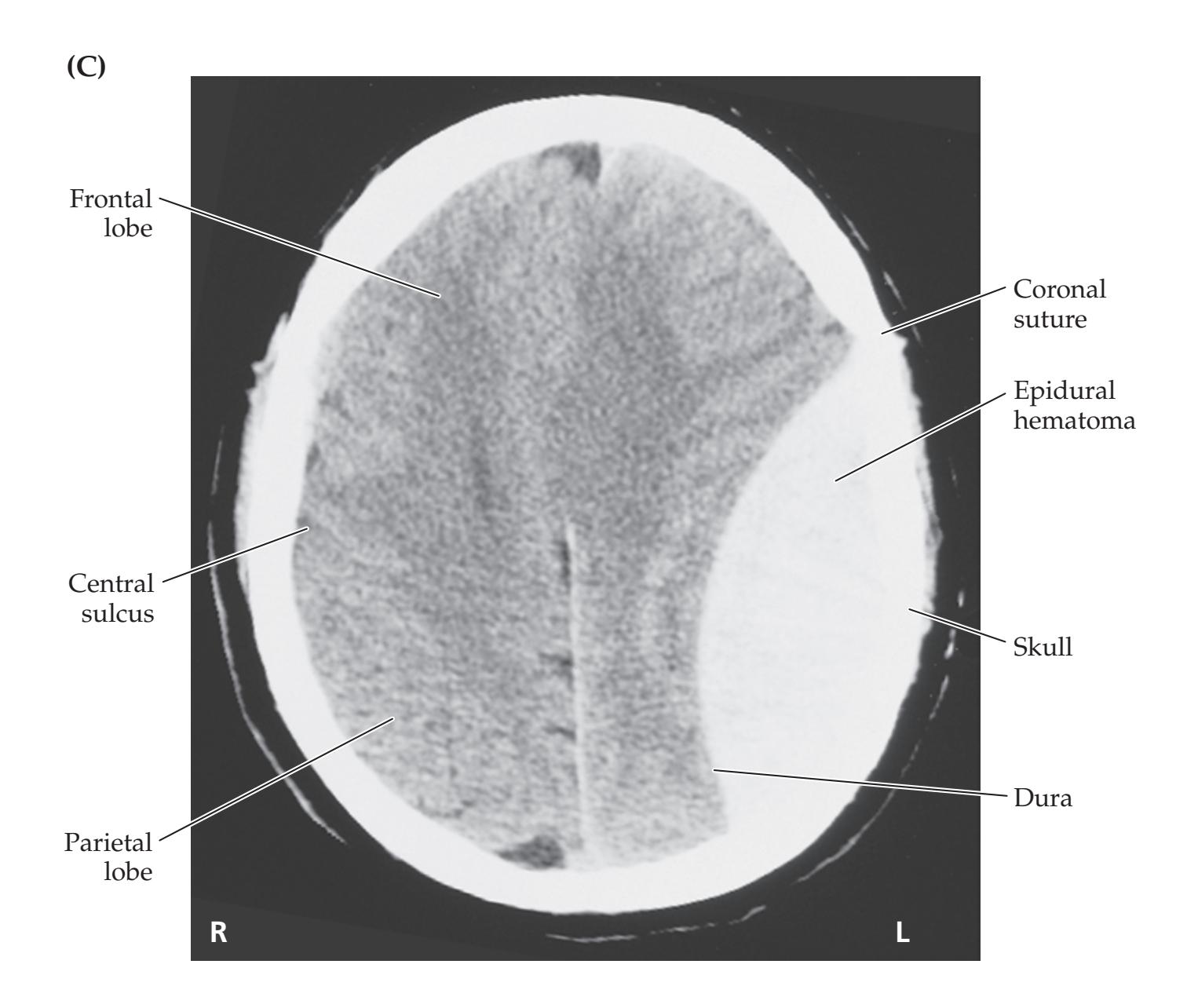

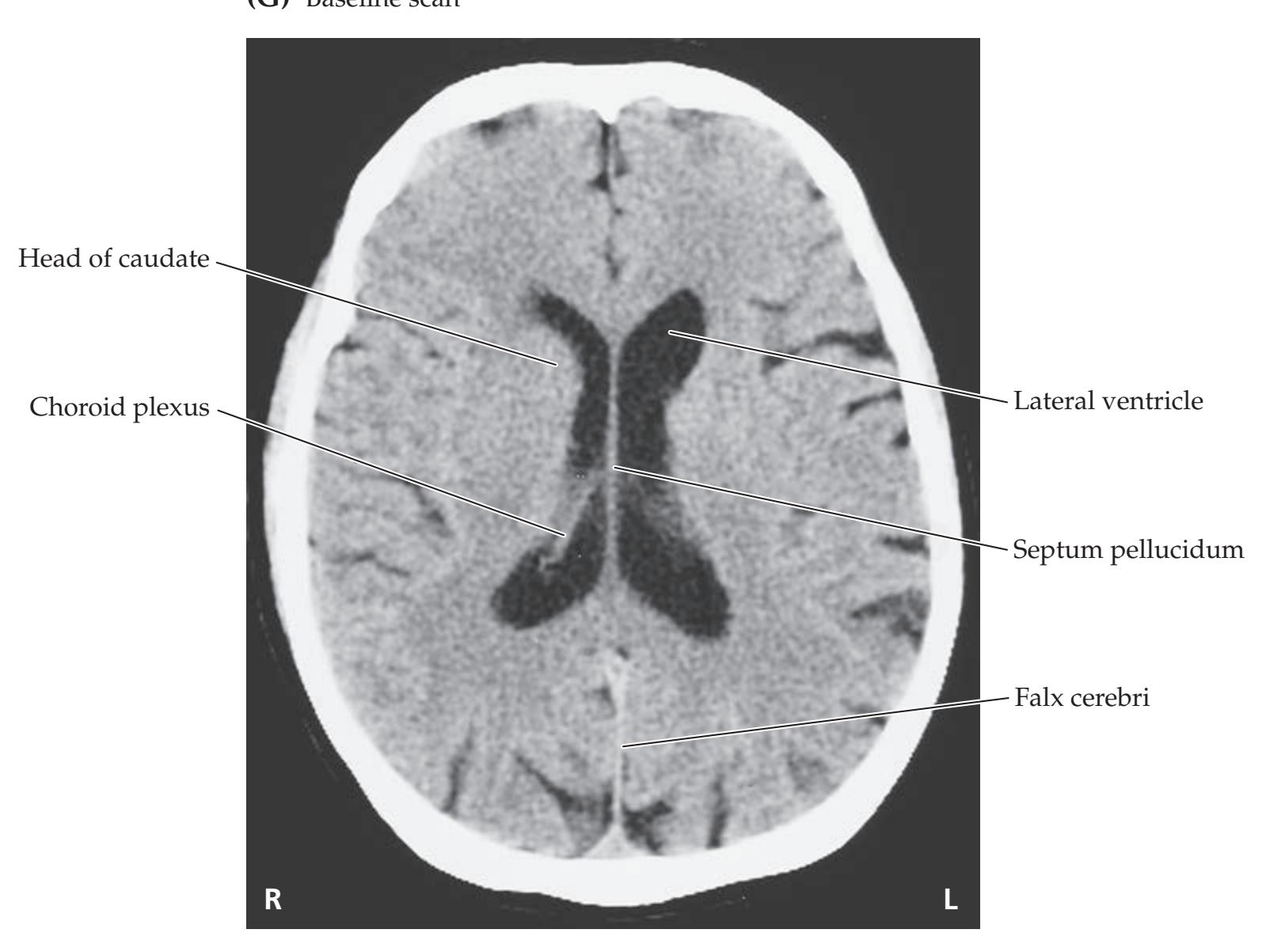

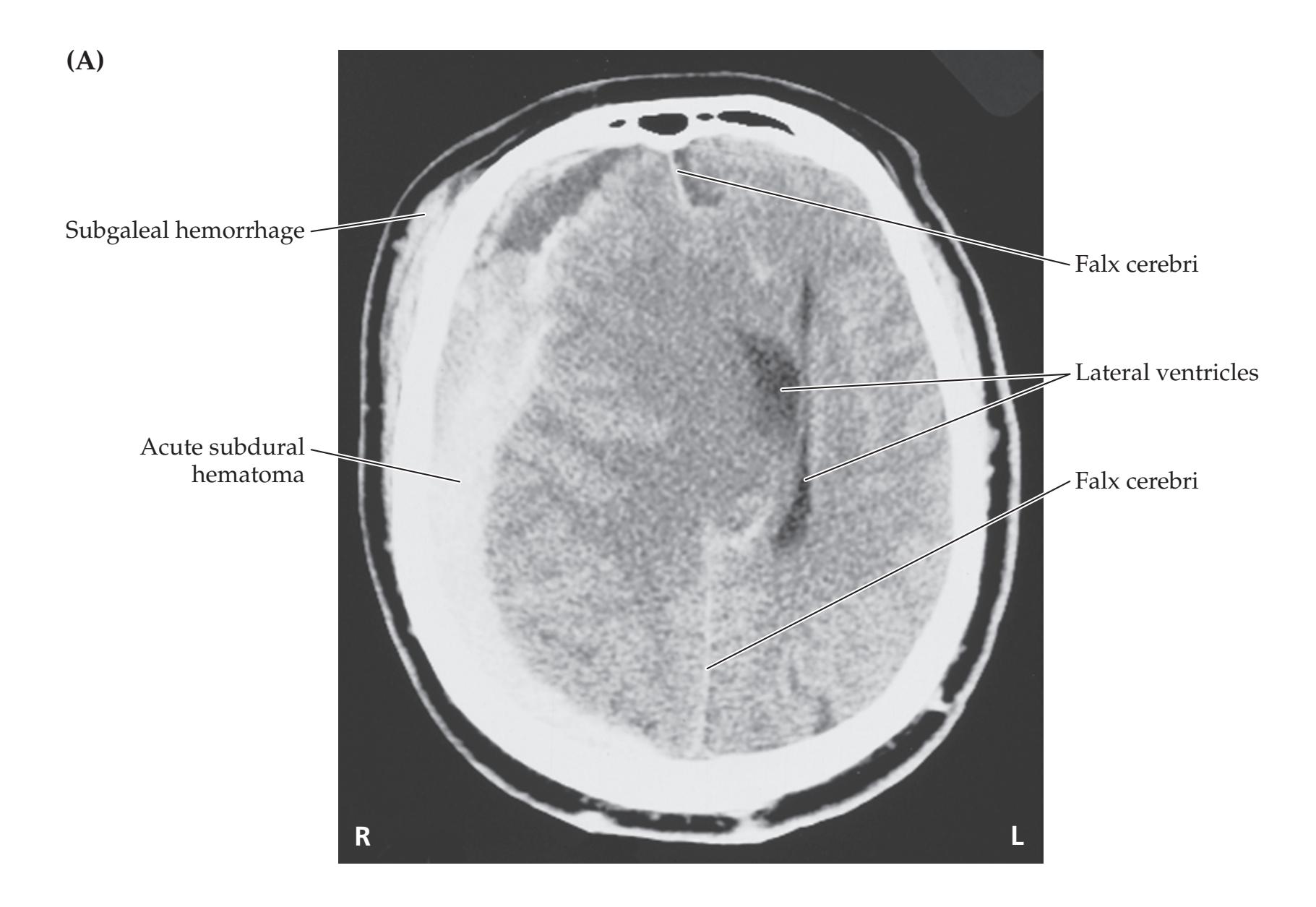

A discussion follows each case, beginning with a summary of the key symptoms and signs. Answers to the questions are provided which refer to anatomical and clinical material presented in the first half of the chapter that is demonstrated by the case. One of the most exciting features of the book is the inclusion of large-format, labeled CT, MRI, or other scans that show the lesion for each patient, and serve as a central tool for teaching neuroanatomy. These images reveal, with striking clarity, both the lesion's location and the anatomy of the system being studied. In addition, these radiographs help the reader develop skill in interpreting the kinds of diagnostic images employed on the wards. The neuroimaging studies for each case are provided in special boxes at least one page turn away from the case questions, so the answers to the questions are not "given away" by the imaging (see below).

The clinical course is also provided for each patient and includes a discussion of how the patient was managed, and what outcome followed. Thus, by the end of each case, students learn the relevant material by application and diagnostic sleuthing rather than by rote memorization.

## **Special Features for Focused Study and Review**

The goal of students reading this book should be to read the material in depth. However, at times they may need to distill it down to the most clinically relevant points, or to focus on material most commonly on the national boards or other examinations. Therefore, several special features have been included to expedite focused study and review in both the print book and e-book (see next section):

- **Boldface type** is used rather differently than in most texts. In addition to identifying the text for all important topics and definitions, boldface is also used to facilitate rapid or focused reading.

- **Review Exercises** appear in the margins throughout the text, highlighting the most important anatomical concepts in each chapter, and providing practice exam questions.

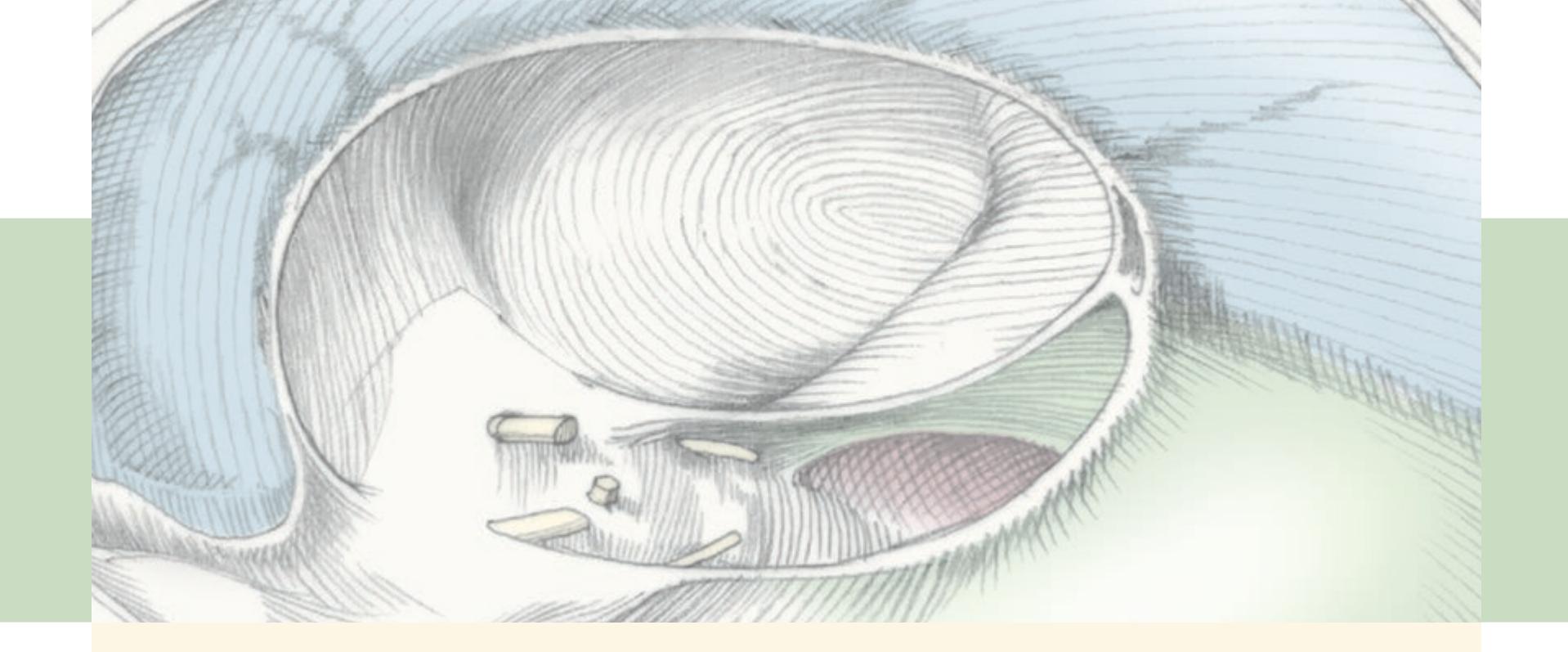

- Helpful **mnemonics** are provided throughout the text, and these are flagged in the margins by a special icon (shown at right) displaying a section of the hippocampus (a structure important in memory formation).

- A **Brief Anatomical Study Guide** appears at the end of each chapter, which summarizes the most important neuroanatomical material, and refers to the appropriate figures and tables needed for focused exam review.

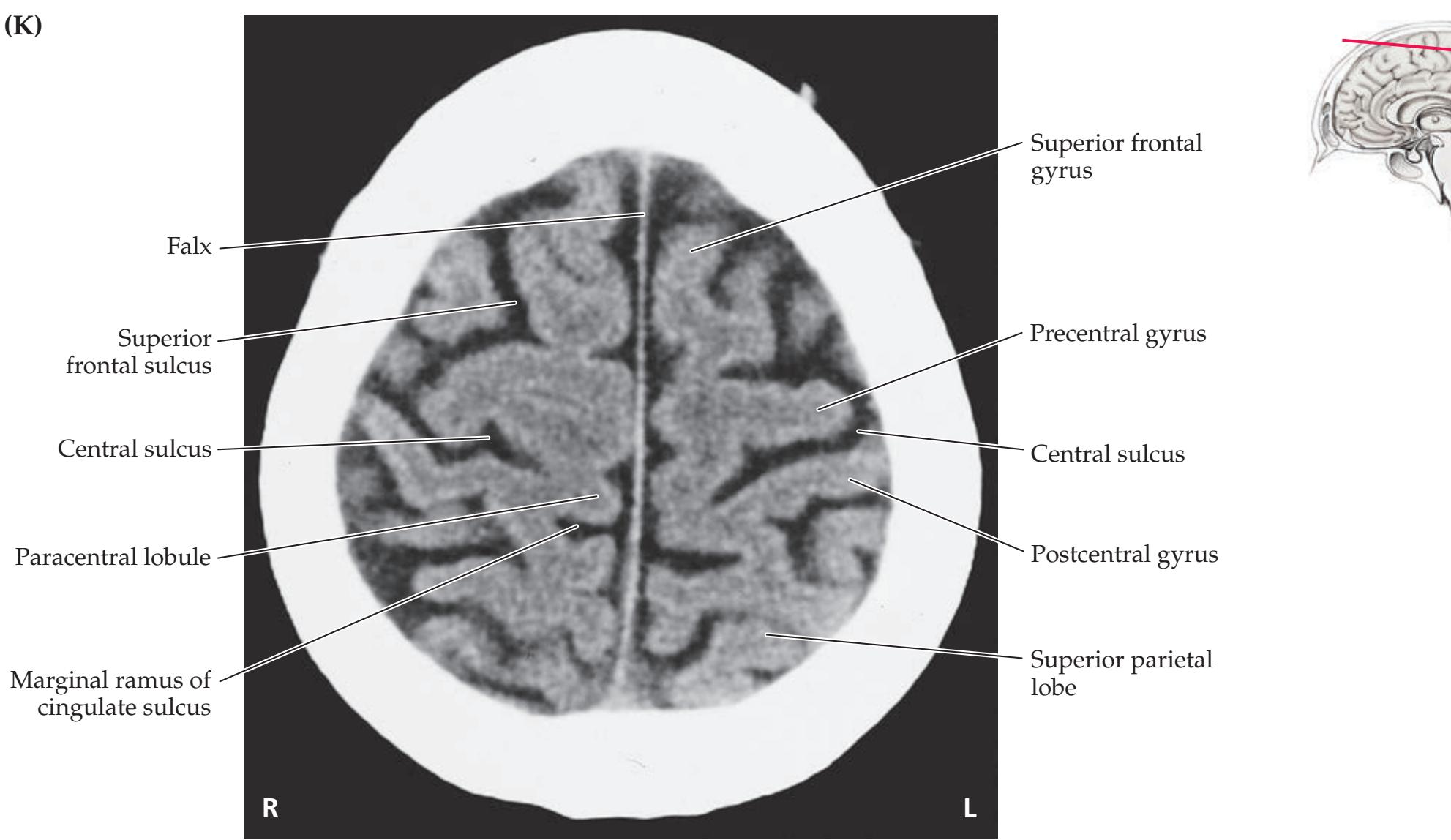

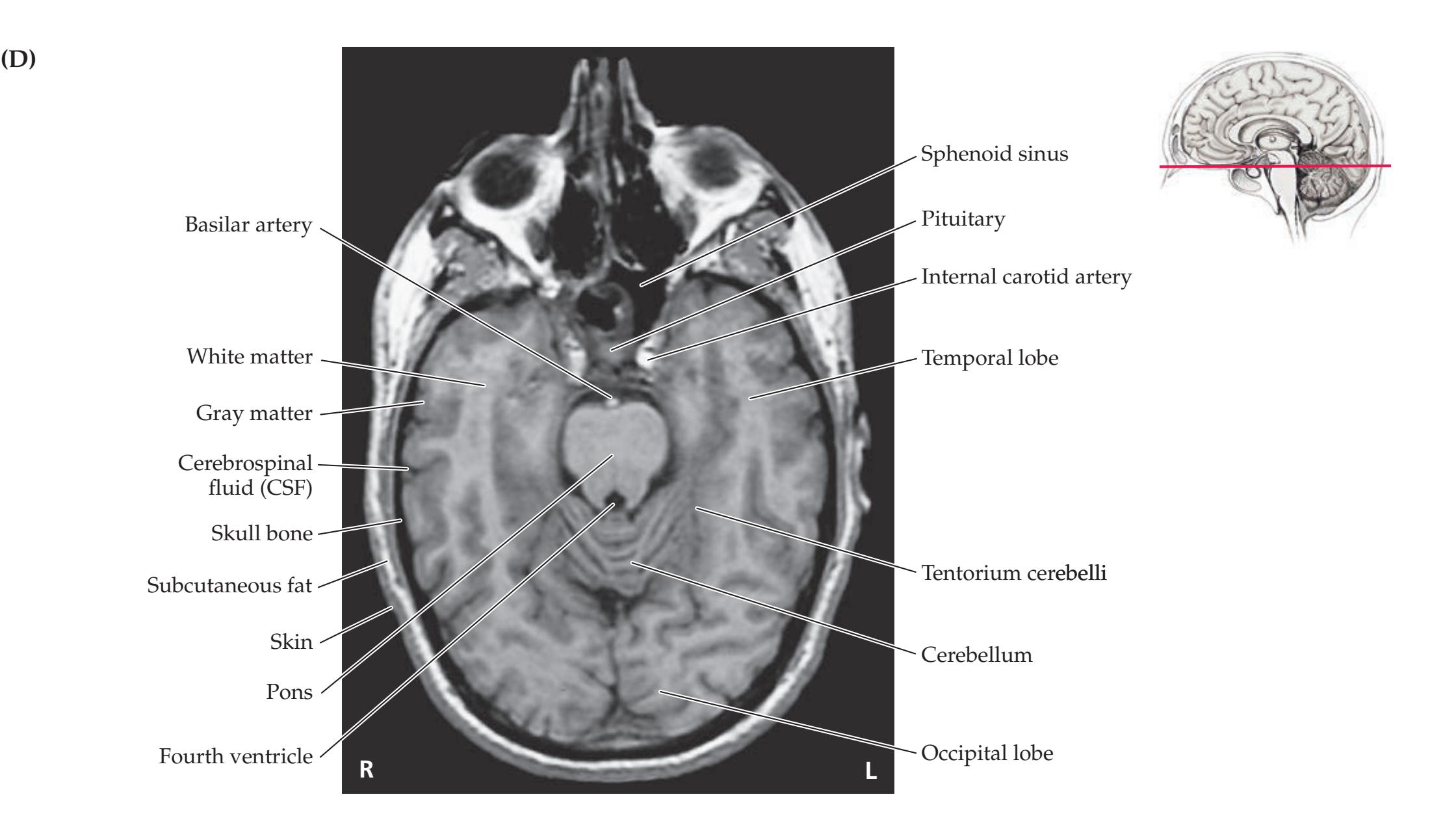

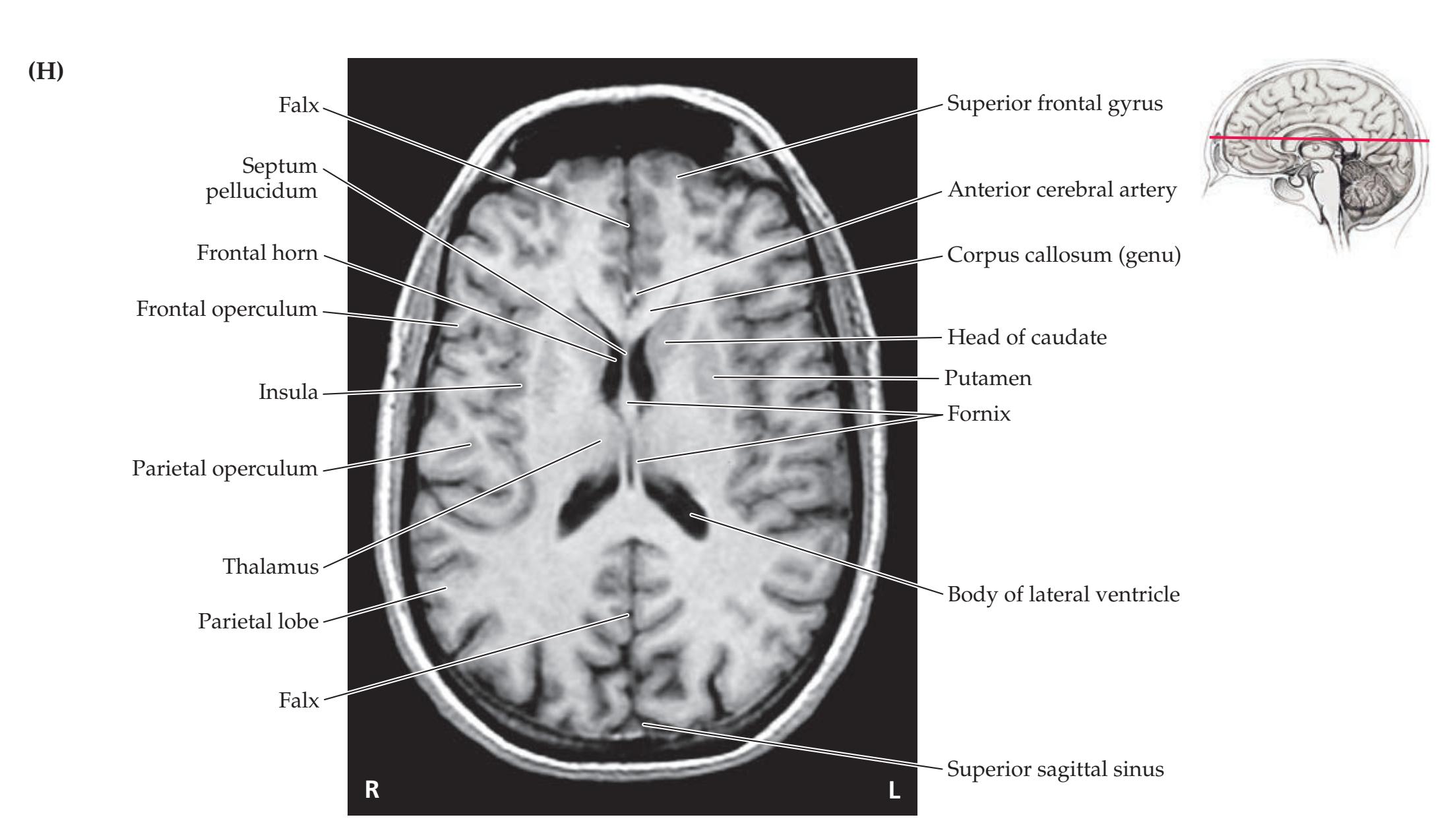

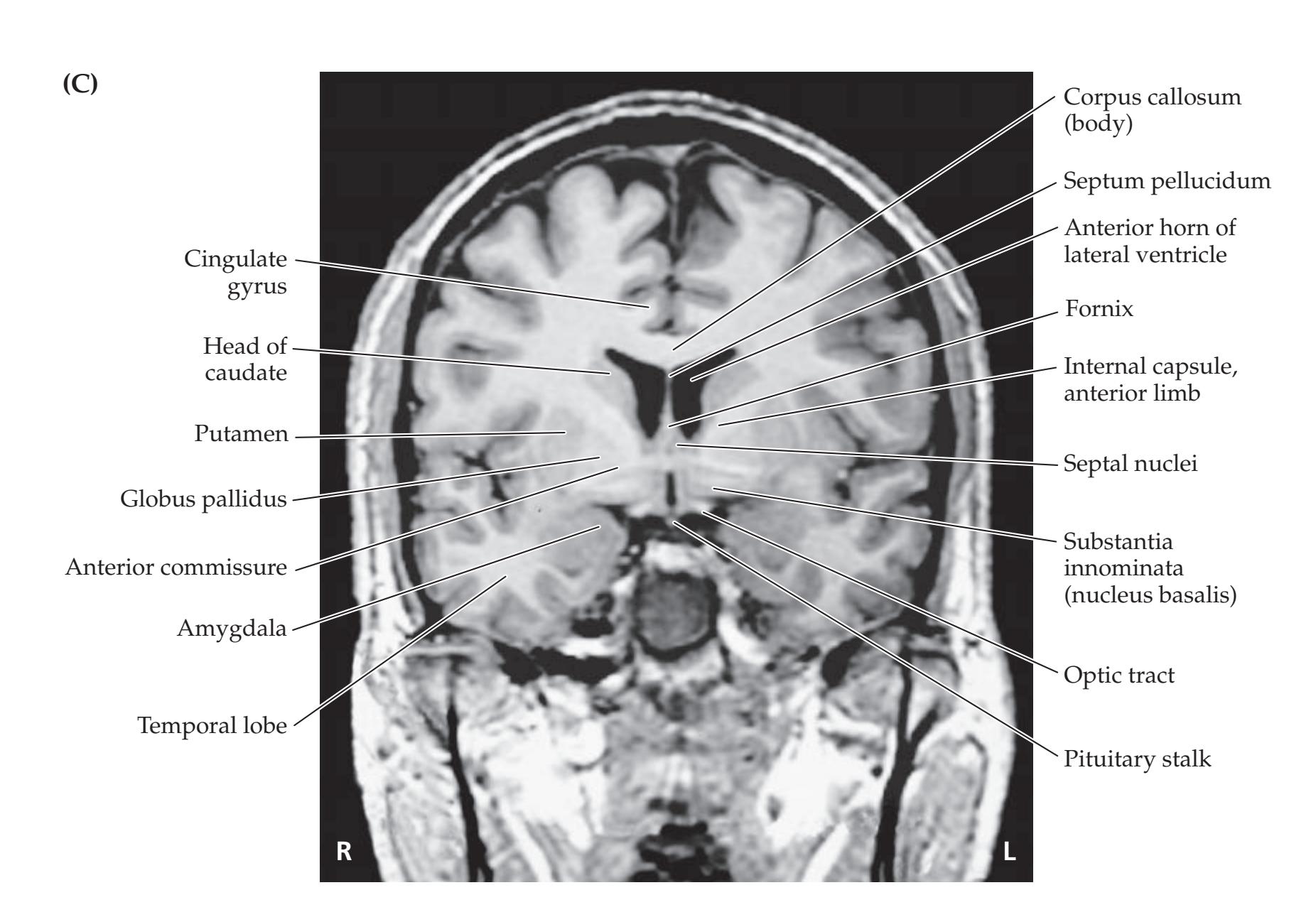

- The **Neuroradiological Atlas** in Chapter 4 also provides a useful review of neuroanatomical structures in three-dimensional space and can be used for reference and comparison to lesions seen in clinical cases.

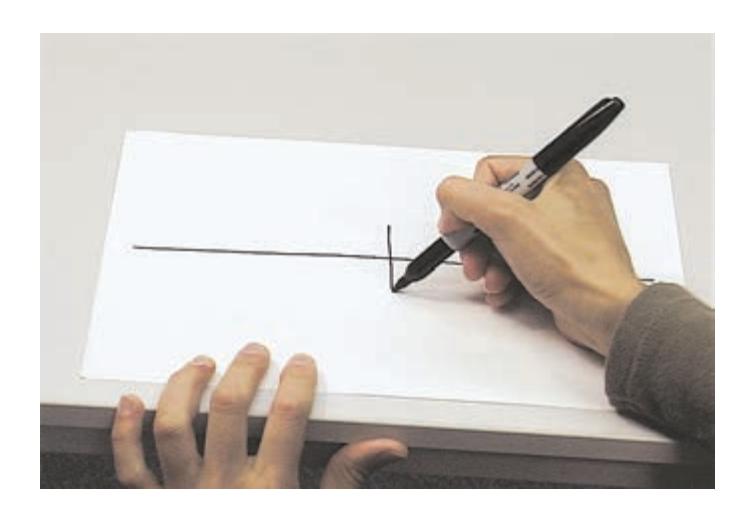

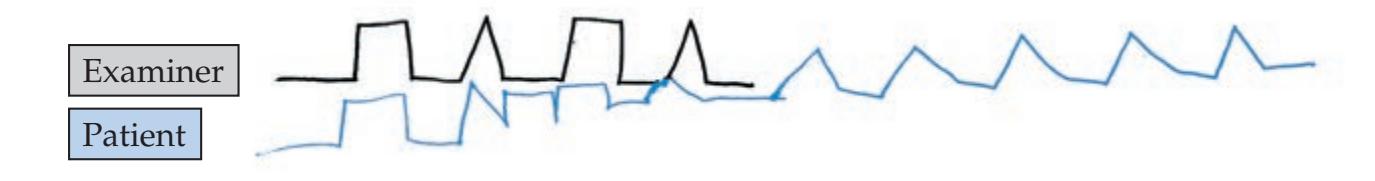

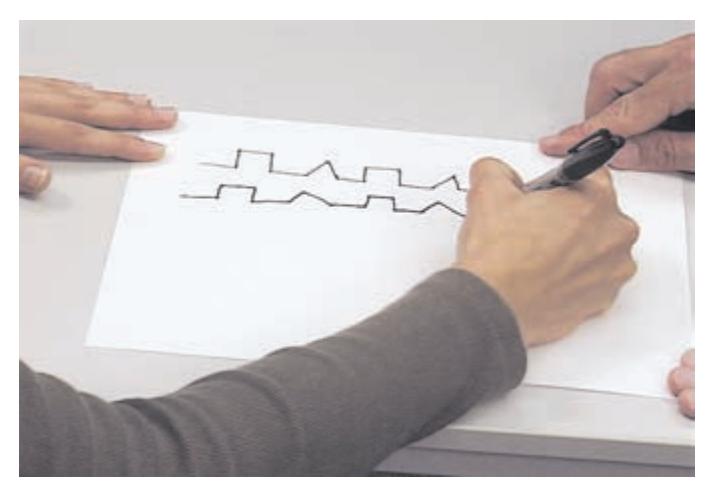

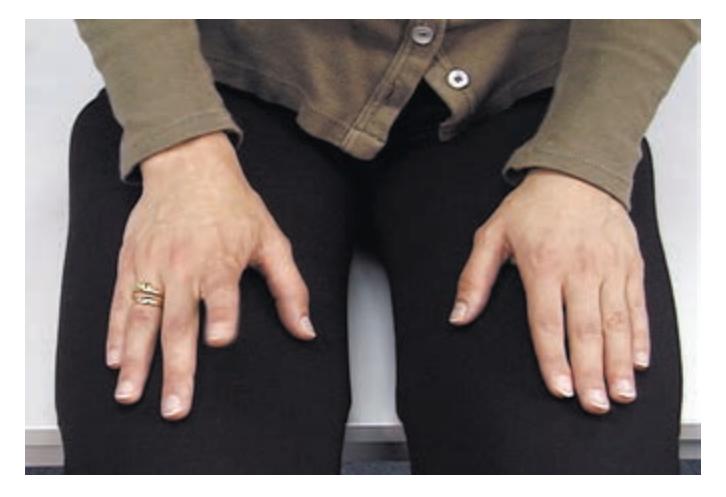

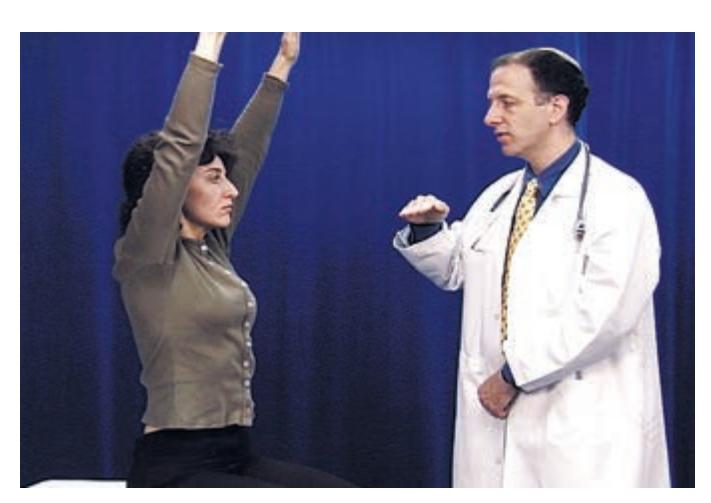

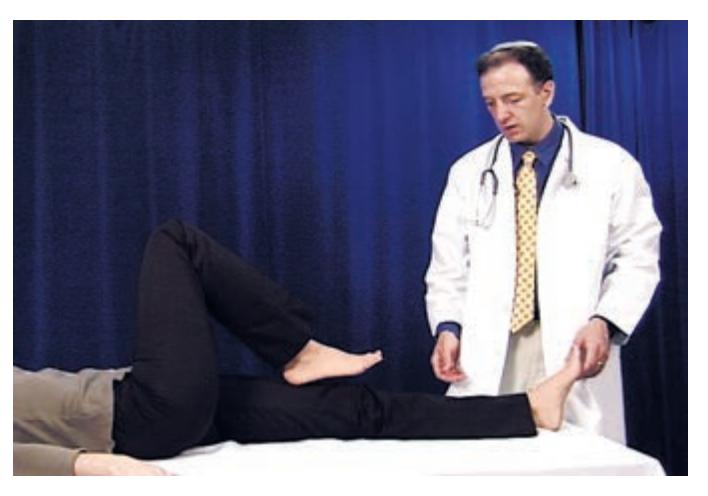

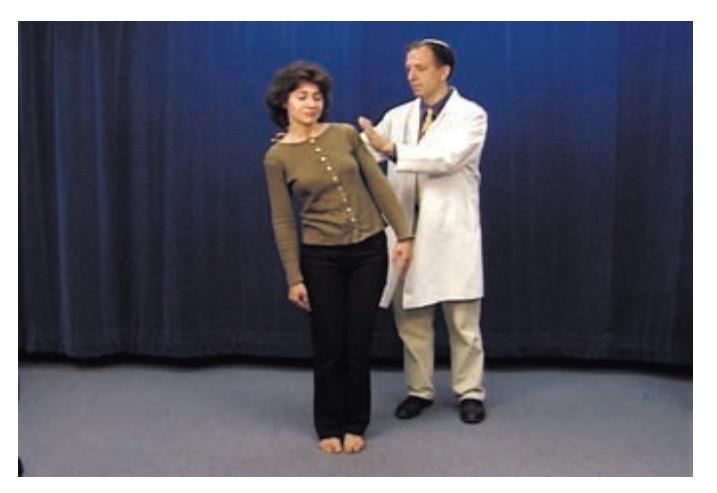

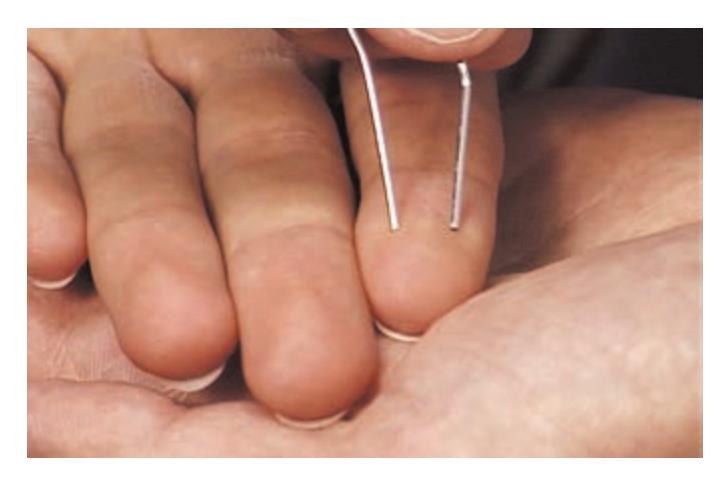

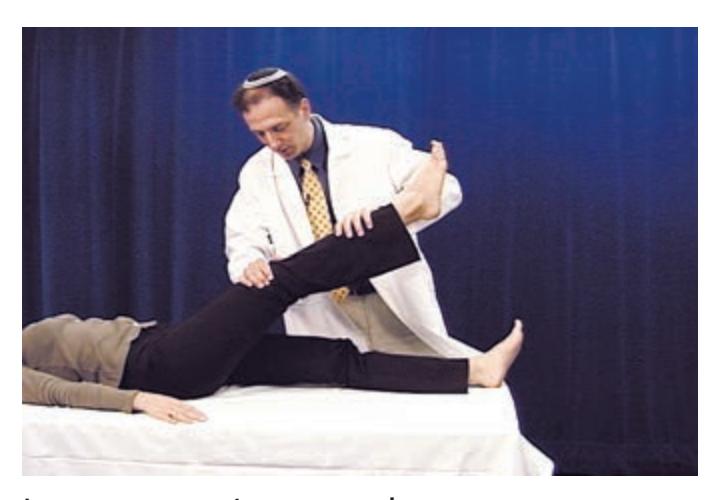

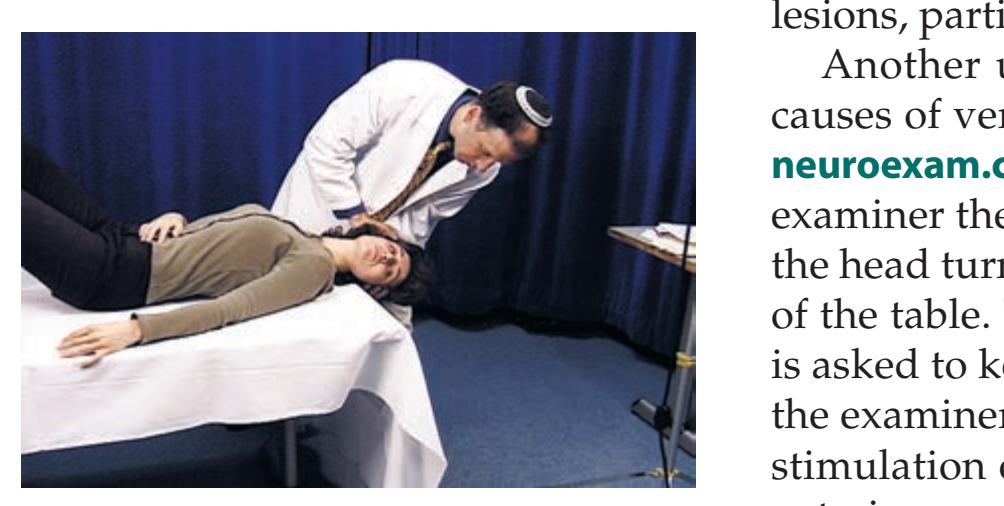

- The **neuroexam.com** website includes much of the text from Chapter 3 describing the neurologic exam and its anatomical interpretation, and also features video demonstrations of each part of the exam that are cited in the text (e.g., "see **neuroexam.com Video 52**"). Selected video frames are also shown in the book margins, as demonstrated here, to illustrate relevant portions of the neurologic exam.

### **REVIEW EXERCISE**

Rapid hand movements **neuroexam.com Video 52**

**xxii** How to Use This Book

- The **Key Clinical Concept** (**KCC**) sections provide a comprehensive introduction to clinical topics in neurology and neurosurgery and enable an efficient review of these topics.

- Finally, the **Clinical Cases** can be used by themselves for study and review, since they consist of anatomical puzzles that reinforce the subject matter for each chapter in the most clinically relevant context. As noted above, the neuroimaging studies for each case are deliberately placed at least one page turn away from the case questions; the location of the images for each case are indicated by page numbers provided immediately after the images are cited in the text.

- The **Additional Cases** section at the end of each chapter, and the **Case Index** at the end of the book provide further cases relevant to the topics in each chapter.

# **e-book: Additional Features for Interactive Study and Review**

The **Neuroanatomy though Clinical Cases e-book** (available through various e-book vendors including RedShelf, VitalSource, and Chegg) provides a highly interactive user experience, including the following additional enhanced features for study and review of neuroanatomy:

- **Interactive Figures** with drag and drop matching of labels to key anatomical structures.

- **Interactive Tables** with multiple-choice selection of key table entries.

- **Interactive Review Exercises** throughout chapters with brief quiz items on key content.

- **Active cross-reference links** for all figures and tables. These enable rapid cross-modality learning and review of visual and factual information throughout the book.

- **Videos** in the text link directly to streaming video on the **neuroexam.com** site.

- **Interactive cases** present thought-provoking questions with answers, clinical images, and outcomes in selectable show-hide format.

- **Interactive Review** section at the conclusion of each chapter includes the following:

- ° List and links to all interactive items in the chapter.

- ° Interactive Brief Anatomical Study Guide with additional quiz items covering all major chapter content.

## **Suggested Course Use**

*Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases* is intended primarily for first- or second-year medical students enrolled in a course in neuroanatomy or neuroscience, but it is a versatile text that could be used in many settings.

The topics covered in the book include all neuroanatomical material required for the medical school board examinations. Although fundamental concepts are emphasized, some advanced subject matter is also provided. Because the book includes chapters on peripheral nerves, students will also find this book useful in their general gross anatomy course in which peripheral nerves are usually covered. The clinically and neuroanatomically oriented How to Use This Book **xxiii**

presentation of neurologic exam skills in this book will be useful to student in both preclinical and clinical settings. The Key Clinical Concept sections in this book also cover the major neurologic and neurosurgical disorders at a level appropriate for medical school pathophysiology courses, clinical rotations, and residents early in their training.

Students of other health professions, especially physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing, dentistry, speech therapy, and neuropsychology will find this textbook useful as well, and it may also be of interest to graduate students of neuroscience. In addition to those learning neuroanatomy, the cases in this book also serve as a resource for advanced medical students in their clinical rotations, and residents in neurology, neurosurgery, and neuroradiology seeking examples of "typical" cases of neurologic disorders. All relevant clinical details are included, while identifiers have been removed to maintain privacy and confidentiality. Because each case is a real patient, the clinical cases in this book are, in effect, a collection of case reports that can serve as a useful resource, especially for teaching purposes and board review. It should be noted, however, that the cases presented here are highly selected for their teaching value and do not constitute an unbiased sampling of the kinds of cases found in clinical practice.

Here are some suggestions for using *Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases* in various courses and curricula:

- For a comprehensive course in **medical school neuroanatomy**, students should read Chapters 2 and 5–18, with selected topics from Chapters 1, 3, 4, and 19. Reading assignments and large class lectures could focus on the Anatomical and Clinical Review sections at the beginning of each chapter. The clinical cases are most effectively discussed in small groups of students, where instructors can help students puzzle through the anatomical localization and diagnosis, and then discuss the neuroradiology and clinical outcome. An **Instructor's Resource Library** is available which contains material that will be useful for lectures, and **additional clinical cases** not found in the book that are ideal for use in small group teaching.

- For medical school courses covering neuroanatomy and other topics in **neuroscience**, additional readings from neuroscience texts such as *Neuroscience* by Purves et al. (2017, Sinauer Associates, an imprint of Oxford University Press) or *Principles of Neural Science* by Kandel et al. (2021, McGraw-Hill) should be provided.

- For a comprehensive course in **clinical disorders of the nervous system**, students should read Chapters 3 and 4, and the Key Clinical Concept sections in Chapters 5–19. *The NeuroExam Video* should be viewed in class, and students referred to **neuroexam.com** for review. Clinical cases could then be presented in small groups, as described above.

- For a course focusing on **neuropsychological disorders** and anatomical correlations, students should read Chapters 2, 10, 18, and 19 and selected parts of Chapters 14 and 16.

- Finally, for a more **basic course in clinical neuroanatomy**, readings could be confined to selected topics in Chapters 2, 5–7, 10–16, and 18.

# **Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases** third edition

# **CONTENTS**

### **Introduction 4**

### **The General History and Physical Exam XXX 4 Category Examples**

Chief Complaint (CC) XXX Chief Complaint (CC) 5 Traumatic disorders such as subdural hematoma; nontraumatic

History of the Present Illness (HPI) XXX History of the Present Illness (HPI) 5 mechanical disorders such as herniated intervertebral disc

Past Medical History (PMH) XXX Past Medical History (PMH) 6

Review of Systems (ROS XXX Review of Systems (ROS) 6 VASCULAR Infarct, hemorrhage, migraine, vascular malformations

> Family History (FHx) XXX Family History (FHx) 6

Social and Environmental History (SocHx/EnvHx) XXX Social and Environmental History (SocHx/EnvHx) 6 EPILEPTIC Focal or generalized seizures

Medications and Allergies XXX Medications and Allergies 6 CSF CIRCULATION Hydrocephalus, pseudotumor cerebri, intracranial hypotension

> Physical Exam XXX Physical Exam 6

Laboratory Data XX Laboratory Data 7 Toxic disorders such as opiate overdose; metabolic disorders such as

Assessment and Plan XXX Assessment and Plan 7 hepatic encephalopathy (DEENO = mnemonic for Drugs, Electrolytes,

**Neurologic Differential Diagnosis XXX Neurologic Differential Diagnosis 7** Endocrine, Nutrition, Organ failure)

**Relationship between the General Physical Exam Relationship between the General Physical Exam** INF/INF/NEO Infectious diseases (e.g., bacterial meningitis); inammatory diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis); neoplastic diseases

**and the Neurologic Exam XXX and the Neurologic Exam 8** (e.g., glioblastoma multiforme)

**Conclusions 10**Chapter

# 1 *Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations*

Case presentations provide the framework for all communications about patient care. They lay down the basic information needed to formulate hypotheses about the location and nature of patients' problems. This information is then used to decide on further diagnostic tests or treatment measures. To diagnose and treat patients such as those described in this book, we must first learn how clinicians generally present

a patient's medical history and the findings from their physical examination. In addition, we must learn how to formulate ideas about neurologic diagnosis and how the neurologic evaluation fits into the general context of patient assessment.

| DATE | TIME | Neurology EW JR | |

|---------|---------------|------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|-----------------|

| 12/1/93 | CC: | Asked to eval 34 y.o. female with nuchal rigidity, RIE, LP | |

| 6:00 pm | HPI: | Pt. & the TB Rxs'd X 6mos, ?HN risk factors, c/o ~late malaise, N/V, SOB & HA. → EW today were initial assessment was notable for nuchal rigidity, photophobia + CXR diffuse patchy opacities. During CXR she had a GTC Sz but then slowly awoke & was responsive + appropriate but in resp distress; intubated & no peritoneal for sedation. Head CT showed mild ventriculomegaly c/w communicating hydroceph, + ?@temporal hypodensity. Was asked to eval pt. ne. ?Safety of LP. Pupils were reportedly PERRL on initial assessment. N Amp/Ceftriaxone started | |

| | PE: | Thin young & intubated sedated P144 BP 114/72 T100.7 pt. breathing spontaneously | |

| ~4:15pm | Initial exam: | Unresponsive | |

| | | @pupil 5mm → 3mm sluggish | fordi-nt, bilat |

| | | @pupil 8mm ineq. unresponsive | |

| | | @EOMS to oculocephalics (HE Korneal → @ | |

| | | @grimace, → cough/gag | |

| | | +)spontaneous mvmts. all 4's, but no udul. & pain | |

| | | (Contd) → | |

**4** Chapter 1

## **Introduction**

NEUROANATOMY is one of the more clinically relevant courses taught in the first years of medical school. Principles learned in neuroanatomy are directly applicable to patient care, not just for the neurologist or neurosurgeon, but also for health care professionals in virtually every other field. However, medical students in their first years and other students of neuroanatomy are often unfamiliar with the basic principles of clinical case presentations used on the wards. Therefore, the first section of this chapter has been provided for the *nonclinician* or the *not-yet-clinician* as a brief orientation. Others may prefer to skip this section. The second section of this chapter discusses the neurologic differential diagnosis, a process through which several possible diagnoses are considered based on the available information. We will use this method when attempting to arrive at diagnoses in the cases throughout the remainder of the book.Abbreviations will be avoided in the case presentations in this book whenever possible, although in reality they are used quite often on the wards. Therefore, some commonly used abbreviations will be introduced in this chapter.

The neurologic exam is only one part of the general physical exam. Nevertheless, the patient should always be treated as a whole and, in addition, much can be learned about neurologic illness from other parts of the physical exam. Therefore, in the final section of this chapter we will discuss the dynamic relationship between the general physical exam and the neurologic exam.

## **The General History and Physical Exam**

While there are variations in personal styles, clinicians adhere to a fairly standard format when presenting cases so that all of the essential information can be succinctly communicated. Since this may be your first exposure to this format, we will first discuss the general structure of the history and physical examination that is used in all fields of medicine. Although the basic structure is always the same, the emphasis varies depending on the specialty. Therefore, in Chapter 3 we discuss the neurologic part of the physical exam in more detail. Note that case presentations in this book focus on the neurologic history and physical exam, although it is crucial to treat the patient as a whole and to never neglect symptoms and signs arising from other body systems. In addition, as described in the discussion that follows, certain features of the general physical exam often provide important information about neurologic illness.

One of the most daunting tasks confronting medical students as they first enter the wards is to master the art of case presentations. When a new patient is admitted to the hospital, it is the responsibility of the medical student and resident on call to obtain a good history and physical exam (H&P) and then to communicate this knowledge to the other members of the medical team. These skills are continually refined throughout a clinician's career as they see more patients.

The level of detail used in obtaining an H&P depends on both the setting and the patient. For example, the appropriate H&P when caring for an unfamiliar patient with multiple, active medical problems is much more detailed than the H&P for a familiar patient who is generally healthy and comes to the outpatient office with an injured finger. As a student's clinical skills develop, the H&P becomes a highly focused tool used both to investigate clinical problems of immediate concern and to screen for other potential problems that may be suspected on the basis of the overall clinical picture.

Remember that the whole point of the H&P is to *communicate*. The goal is to present the important points of the case to one's colleagues in the form of an interesting "story." They can then contribute to the patient's care through Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations **5**

discussion of the case or by taking care of the patient in the middle of the night when the people who originally admitted the patient may be sound asleep at home. As one learns more clinical medicine, one gradually comes to know the difference between critical details not to be overlooked and irrelevant side issues that put listeners to sleep. This distinction is often surprisingly subtle, but it makes all the difference in effective case presentations.

The general format most commonly used for an H&P contains the following elements, which we will discuss in more detail in the sections that follow:

- Chief complaint, or why the patient now requires care

- History of the present illness

- Past medical history

- Review of systems

- Family history

- Social and environmental history

- Medications and allergies

- Physical exam

- Laboratory data

- Assessment and plan

### *Chief Complaint* **(***CC***)**

This is a succinct statement that includes the patient's age, sex, and presenting problem. It may also include one or two very brief pieces of pertinent historical data.

**Example:** "The patient is a 53-year-old man with a history of hypertension now presenting with crushing substernal chest pain of 1 hour's duration."

### *History of the Present Illness* **(***HPI***)**

This is the complete history of the *current* medical problem that brought the patient to medical attention. It should include possible risk factors or other causes of the current illness as well as a detailed chronological description of all symptoms and prior care obtained for this problem. Pertinent negative information (symptoms or problems that are *not* present) helps exclude alternative diagnoses and is as important as pertinent positive information. Related medical problems can be mentioned as well; however, those that are not directly relevant to the present illness are usually covered instead in the section on past medical history (discussed in the next section).

**Example:** "The patient has cardiac risk factors consisting of hypertension for 15 years and a family history of coronary artery disease. He does not smoke, nor does he have diabetes or elevated cholesterol. He has not had previous myocardial infarction. For the past 5 years he has had a stable pattern of chest pain on exertion, brought on by walking up two or more flights of stairs, lasting less than 5 minutes, not accompanied by other symptoms. The pain is relieved by rest and sublingual nitroglycerin. He has refused to undergo further cardiac workup, such as exercise stress testing, in the past. He denies symptoms of congestive heart failure and has no history of peripheral vascular or cerebrovascular disease. Today while sitting at his desk at work, he developed sudden 'crushing' substernal chest pain and pressure radiating to his neck, accompanied by tingling of the left arm, shortness of breath, sweating, and nausea without vomiting. The pain was not relieved by three sublingual nitroglycerin tablets, and his coworkers called an ambulance to bring him to the emergency room, where he was afebrile with pulse 100, BP 140/90, and respiratory rate 20, and had an EKG with ST elevations, suggesting anterolateral myocardial ischemia. His pain

**6** Chapter 1

was initially relieved by IV nitroglycerin and 2 mg of morphine, but then returned, lasting over 20 minutes with continued ST elevations. He is now being admitted for urgent cardiac catheterization."

### *Past Medical History* **(***PMH***)**

Prior medical and surgical problems not directly related to the HPI are described here.

**Example:** "The patient has a history of a mildly enlarged prostate gland. He had a right inguinal hernia repair in 1978."

### *Review of Systems* **(***ROS***)**

A brief, head-to-toe review of all medical systems—including head, eyes, ears, nose and throat, pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, OB/GYN, dermatologic, neurologic, psychiatric, musculoskeletal, hematological, oncologic, rheumatological, endocrine, infectious diseases, and so on—should be pursued to pick up problems or complaints missed in earlier parts of the history. If something comes up that is relevant to the HPI, it should be inserted in the HPI section, not buried in the ROS.

**Example:** "The patient has had mild upper respiratory symptoms for the past 4 days with nasal congestion but no cough, temperature, or sore throat."

### *Family History* **(***FHx***)**

This section should list all immediate relatives and note familial illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma, heart disease, cancer, depression, and so on, especially those relating to the HPI. Family tree format is often a succinct and clear way to present these data.

**Example:** "Patient's mother died at 64 of myocardial infarction, had hypertension. Father had myocardial infarction at 52, had diabetes, died at 73 of stroke. Brother, 47 years old, healthy. Two children, healthy."

### *Social and Environmental History* **(***SocHx/EnvHx***)**

This section should include the patient's occupation, family situation, travel history, sexual history (if not covered in ROS), and other relevant habits.

**Example:** "Electrical engineer. Married with two children. No recent travel. Denies ever smoking cigarettes or using drugs. Drinks 1–2 beers on Sundays."

### *Medications and Allergies*

This section should list all medications currently being taken by the patient (including herbal or over-the-counter drugs), as well as any known general or drug allergies.

**Example:** "Lisinopril 20 mg PO daily. Metoprolol 100 mg PO daily. Sublingual nitroglycerin as needed. No allergies. NKDA (no known drug allergies)."

### *Physical Exam*

The examination generally proceeds from head to toe and includes the following sections:

- General appearance—for example, "A diaphoretic man in clear discomfort."

- Vital signs—temperature (T), pulse (P), blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate (R)

- HEENT (head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat)

- Neck

Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations **7**

- Back and spine

- Lymph nodes

- Breasts

- Lungs

- Heart

- Abdomen

- Extremities

- Pulses

- Neurologic (see Chapter 3)

- Rectal

- Pelvic and genitalia

- Dermatologic

### *Laboratory Data*

This comprises all diagnostic tests, including blood work, urine tests, electrocardiogram, and radiological tests (chest X-rays, CT scans, etc.).

### *Assessment and Plan*

The **assessment** section usually begins with a one- or two-sentence **summary**, or **formulation**, that encapsulates the patient's main clinical features and most likely diagnosis. In more diagnostically uncertain cases, a brief discussion is added to the assessment, including a **differential diagnosis**—that is, a list of alternative possible diagnoses. With neurologic disorders, this discussion is often broken down into two sections: (1) localization and (2) differential diagnosis.

The **plan** section immediately follows the assessment and is usually broken down into a list of problems and proposed interventions and diagnostic procedures.

**Example:** "This is a 53-year-old man with cardiac risk factors of hypertension and family history of coronary disease who presents with substernal chest pain and EKG changes suggestive of anterolateral wall myocardial infarction.

- 1. Coronary artery disease: Patient to undergo cardiac catheterization for diagnosis and treatment including angioplasty/stenting as needed. Admit post-procedure to cardiac intensive care unit for further care. Will check serial EKGs and cardiac enzymes to determine whether the patient has had a myocardial infarction.

- 2. Further cardiac workup: To include echocardiogram and an exercise stress test if cardiac enzymes and catheterization are negative. Resume prior medications and follow up as outpatient."

## **Neurologic Differential Diagnosis**

Reaching the correct diagnosis in patients with neurologic disorders sometimes presents a considerable challenge. As noted in the previous discussion, the assessment section of the H&P is therefore often broken down into several logical steps to facilitate this thought process. The first step is **localization** based on neuroanatomical clues gleaned from the H&P. This integration of anatomical and clinical knowledge will be the focus of this book. However, we will also briefly discuss the next step, the **neurologic differential diagnosis**.

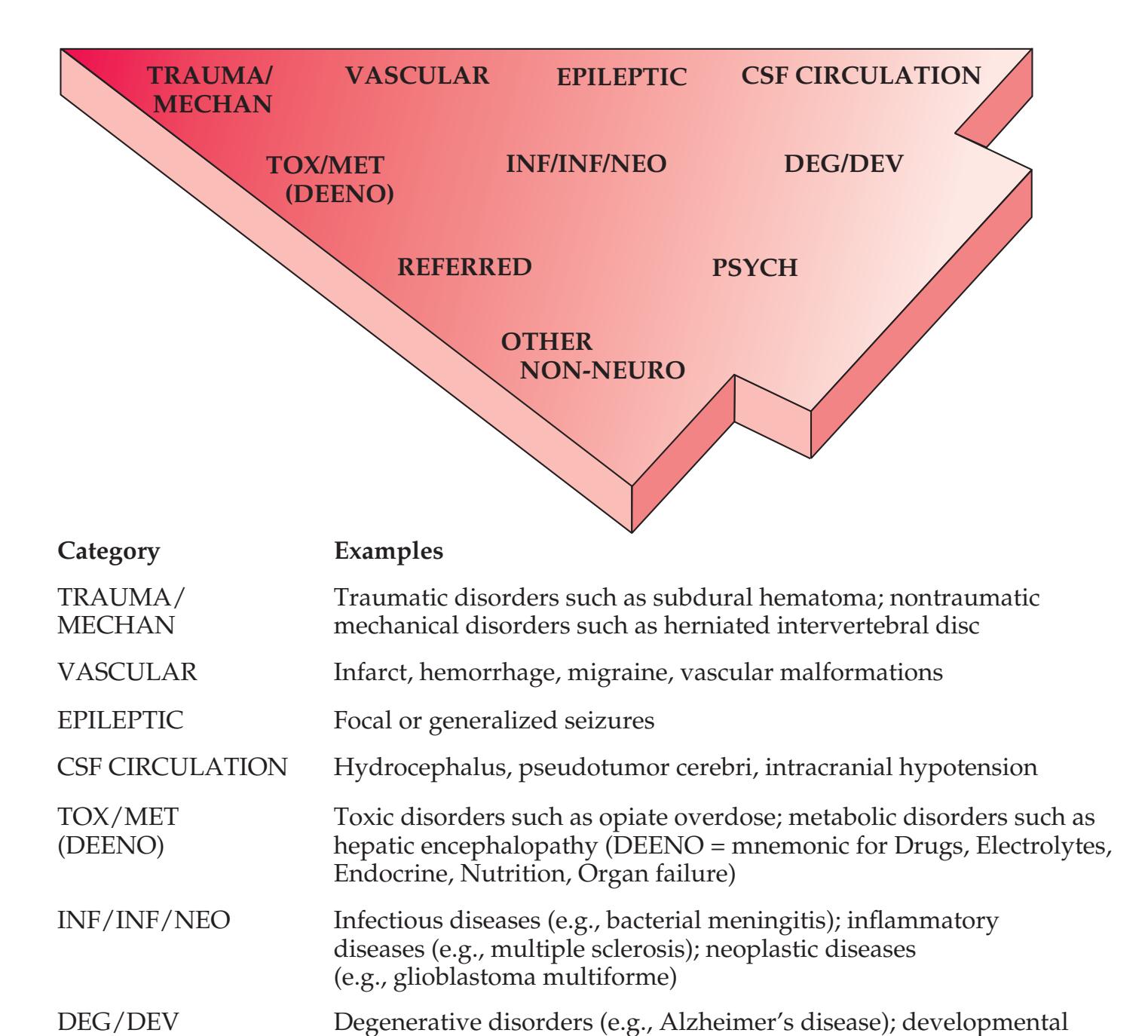

When the diagnosis is uncertain and multiple possibilities must be considered, it is often helpful to have a mnemonic device handy, especially while being questioned on rounds by a more senior clinician. Such a mnemonic, the Arrowhead of Neurologic Differential Diagnosis, is shown in **Figure 1.1**. Disorders that tend to be more acute and require more immediate attention

**8** Chapter 1

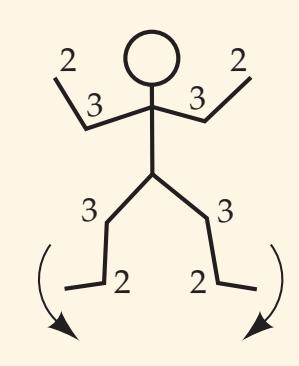

**FIGURE 1.1 Arrowhead of Neurologic Differential Diagnosis** More acute diagnoses are often (but not always) at the top left point, and along the outer edges of the arrow. Examples and explanations of abbreviations are listed.

appear along the top and left leading edges of the arrowhead; disorders that are usually more chronic in nature appear on the inside. In visualizing and prioritizing one's clinical interventions, it can therefore be useful to move from the point on the left along the top row, and then along each subsequent row from left to right.

Loss of consciousness due to cardiac arrhythmia, impaired gait due

disorders (e.g., tuberous sclerosis)

REFERRED Left arm parasthesias due to cardiac ischemia PSYCH Major depression, conversion disorder

to joint deformity

OTHER NON-NEURO

### **Relationship between the General Physical Exam and the Neurologic Exam Blumenfeld 3e** *Neuroanatomy OUP/Sinauer Associates* 1/31/2020

The neurologic exam is *part of the general physical exam*. Thus, although the neurologic exam is covered separately in Chapter 3, in reality the neurologic exam and the general physical exam should always be done and described as a single unit. The patient must be treated as a whole, with problems in different systems given priority depending on the situation. In addition, essential information about neurologic disease can be gleaned from all portions of the general physical exam. Some examples are given here (for explanations of unfamiliar terms refer to the Key Clinical Concepts sections throughout the rest of this book, or consult the Index): **BLUM3e\_01.01**

• **General appearance**. How a person appears and behaves throughout the exam provides a wealth of information about his or her mental status and motor system.

Introduction to Clinical Case Presentations **9**

- **Vital signs**. Hypertension, bradycardia, and other changes can be seen in elevated intracranial pressure. Exaggerated orthostatic changes (between reclining and upright positions) in heart rate and blood pressure can be seen in autonomic dysfunction and spinal cord injuries. Respiratory pattern provides important information about brainstem functioning. Elevated temperature suggests infection or inflammation, which may involve the nervous system.

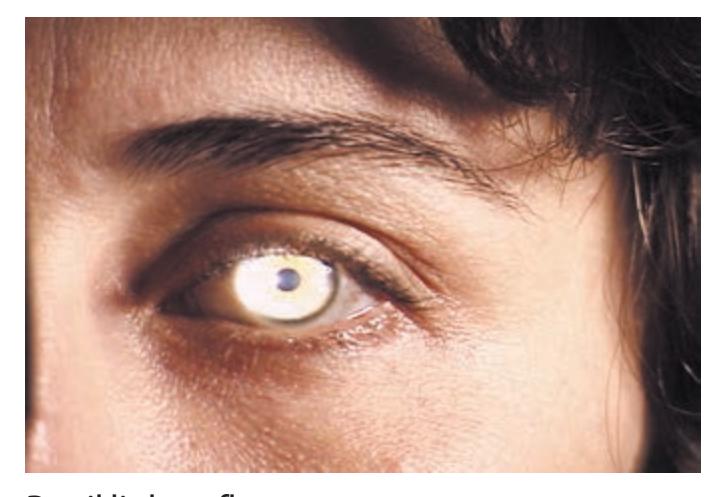

- **HEENT**. Head shape can be a clue to congenital abnormalities, hydrocephalus, or tumors. Careful examination of the head, ears, and nose is essential in cranial trauma. Tongue abnormalities can suggest nutritional deficiencies, which may have neurologic manifestations. Oral thrush suggests immune dysfunction, which can predispose patients to a host of neurologic disorders. Palpation of the temporal and supraorbital arteries can give clues about vasculitis and collateral blood flow in cerebrovascular disease. A whooshing sound called a *bruit* can sometimes be heard with the stethoscope when intracranial vascular disease or arteriovenous malformations are present. Scalp tenderness may be present in migraine. The funduscopic exam is so relevant to neurologic disease that it is often included as part of the neurologic exam itself.

- **Neck**. Neck stiffness can be a sign of meningeal irritation. Cervical bruits can be heard with carotid artery disease. Thyroid abnormalities can cause mental status changes, eye movement disorders, and muscle weakness.

- **Back and spine**. Tenderness, misalignment, and curvature can give important information about possible fractures, metastases, osteomyelitis, and so on. Muscle stiffness and tenderness are diagnostically helpful in cases of back pain.

- **Lymph nodes**. Enlarged lymph nodes can be seen in neoplastic, infectious, and granulomatous disorders, which may involve the nervous system.